Background: PIP2 generated by PIPKI family members regulates many cellular functions, and PIP2 is a PI3K substrate.

Results: Loss of PIPKIγ or PIPKIγi2 impaired Akt activation. PIPKIγi2 and Src activate Akt and anchorage-independent growth.

Conclusion: PI3K/Akt signaling is regulated by coupling with PIPKIγ.

Significance: The coupling of PIPKIγ and PI3K indicates a mechanism for Akt activation that enhances oncogenic growth.

Keywords: Akt PKB, phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), phosphatidylinositol kinase (PI kinase), phosphoinositide, Src, PIPKIgamma, PIPKIgammai2, Akt, Src, oncogenic growth

Abstract

The assembly of signaling complexes at the plasma membrane is required for the initiation and propagation of cellular signaling upon cell activation. The class I PI3K and the serine/threonine-specific protein kinase Akt signaling pathways (PI3K/Akt) are often activated in tumors. These pathways are initiated by the generation of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) by PI3K-mediated phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2), synthesized by phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase (PIPKI) enzymes. The mechanism of how tumor cells recruit and organize the PIP2-synthesizing enzymes with PI3K in the plasma membrane for activation of PI3K/Akt signaling is not defined. Here, we demonstrated a role for the phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase Iγ (PIPKIγ) in PI3K/Akt signaling. PIPKIγ is overexpressed in triple-negative breast cancers. Loss of PIPKIγ or its focal adhesion-targeting variant, PIPKIγi2, impaired PI3K/Akt activation upon stimulation with growth factors or extracellular matrix proteins in different tumor cells. PIPKIγi2 assembles into a complex containing Src and PI3K; Src was required for the recruitment of PI3K enzyme into the complex. PIPKIγi2 interaction with Src and its lipid kinase activity were required for promoting PI3K/Akt signaling. These results define a mechanism by which PIPKIγi2 and PI3K are integrated into a complex regulated by Src, resulting in the spatial generation of PIP2, which is the substrate PI3K required for PIP3 generation and subsequent Akt activation. This study elucidates the mechanism by which PIP2-generating enzyme controls Akt activation upstream of a PI3K enzyme. This pathway may represent a signaling nexus required for the survival and growth of metastasizing and circulating tumor cells in vivo.

Introduction

Tumor cells receive survival and proliferative signals from diverse stimuli, such as growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular matrix (ECM)2 proteins (1). Among signaling pathways initiated by these stimuli, PI3K/Akt signaling is one of the most common pathways implicated in tumor cell growth and survival (2–4). The PI3K enzymes activated by these diverse stimuli convert PIP2 into PIP3, promoting the recruitment and activation of cytosolic proteins, PDK1 and Akt, to the plasma membrane and initiating PI3K/Akt signaling cascades (2–4). Cancer cells exploit various mechanisms to activate and sustain PI3K/Akt signaling (2–4). Most of them are associated with PTEN loss or the activation of the PI3K enzyme due to mutations in its catalytic subunit (2–4). However, the functional role of lipid kinases that synthesize PIP2, precursor for PIP3, remains poorly explored in the regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling. The localized synthesis of PIP2 and PIP3 suggest that lipid kinases generating PIP2 and PIP3 work together in a coordinated and regulated manner for Akt activation. In the context of highly divergent mechanisms for Akt activation in oncogenesis, the precise understanding of how PIP2- and PIP3-generating lipid kinases work together to regulate PI3K/Akt signaling paves the way for the development of a novel therapeutic approach in controlling the PI3K/Akt signaling axis in cancer.

In mammalian cells, PIP2 is predominantly synthesized by type I PIPK enzymes (classified into PIPKIα, PIPKIβ, and PIPKIγ), which are targeted to distinct subcellular compartments via interactions with specific binding partners, which are often PIP2 effector molecules (5–9). These interactions facilitate PIP2 control of diverse cellular functions. PIPKIα is predominantly localized to the nucleus and controls the nuclear events, whereas PIPKIβ is targeted to perinuclear regions/endosomes (9, 10). PIPKIγ is expressed as at least six splice variants (PIPKIγi1, PIPKIγi2, PIPKIγi3, PIPKIγi4, PIPKIγi5, and PIPKIγi6) in mammalian cells (11, 12); among them, PIPKIγi2 can be targeted to the cell-matrix interface via an interaction with talin and plays role in focal adhesion assembly (13–15), whereas PIPKIγi4 and PIPKIγi5 are localized to the nucleus and endosomes, respectively (11, 16). Src phosphorylation of PIPKIγi2 regulates its interaction with talin and its targeting to focal adhesion sites (17). Furthermore, Src and PIPKIγi2 are directly interacting partners, both required for oncogenic growth of tumor cells (18). Recently, PIPKIγ has been shown to modulate breast cancer metastasis, although the specific isoforms involved were not defined (19).

The class I PI3K enzymes are heterodimers of two distinct subunits, an adaptor (e.g. p85, p50, and p55) and a catalytic (e.g. p110α, p110β, and p110δ) (2–4). PI3K is rapidly recruited to activated growth factor receptors (SH2 domain of the adaptor subunit mediating the interaction to the phosphorylated YXXM motif of the receptor) or integrin-mediated adhesion complex (via interaction with focal adhesion kinase in the adhesion complex), promoting its activation and PIP3 synthesis (2, 20). For PIPKI enzymes, the mechanism by which they are recruited to the proximity of the activated growth factor receptors or integrin-mediated adhesion complex to synthesize the spatial pool of PIP2 is not understood. This may be a crucial mechanism for providing a discrete pool of PIP2 required for PIP3 synthesis and Akt activation. Therefore, we embarked on a systematic investigation to define the role of PIPKI enzymes in PI3K/Akt activation in response to stimulation with growth factors and ECM proteins.

Here we show that in a wide variety of cell lines, PIPKIγ was the major PIPKI enzyme contributing to PI3K/Akt signaling in response to activation of growth factor and adhesion receptors in suspension condition. The loss of PIPKIγi2, a focal adhesion-targeted variant of PIPKIγ, recapitulated the effect of PIPKIγ knockdown in PI3K/Akt activation. PIPKIγi2 integrated into a complex with Src and PI3K. Src mediated the incorporation of both PIPKIγi2 and PI3K into the complex via Src association with the p85 subunit of PI3K. The co-expression of PIPKIγi2 with Src resulted in sustained activation of PI3K/Akt. Furthermore, PIPKIγi2 and Src interaction, and its lipid kinase activity were required for PI3K/Akt activation. These results define a mechanism by which PIPKIγi2 functions with the proto-oncogene Src to activate and sustain the PI3K/Akt signaling required for the anchorage-independent or oncogenic growth of tumor cells.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

Antibodies used were as follows: pAkt (193H12), Akt (11E7), pErk1/2 (9101) and Erk1/2 (9102), Src (2108S), p110α (4255s), p110β (3011s), and p85 (4292) were purchased from Cell Signaling; antibody for HA (MMS-101R) was purchased from Covance. Antibodies for PIPKIα, PIPKIγ, and PIPKIγi2 were developed in the laboratory (13, 17, 21).

DNA Constructs and siRNA

DNA constructs used in the study were described previously (18, 22). siRNA oligonucleotides used were as follows: control siRNA, CCUUGGUGACUCGUAGUUU; siPIPKIγi2, GAGCGACACAUAAUUUCUA; siPIPKIγi5, GGAUGGGAGGUACUGGAUU; siPIPKIγ, GCCACCTTCTTTCGAAGAA; siPIPKIα, GAAGUUGGAGCACUCUUGG; siSrc, GGCUCCAGAUUGUCAACAA and GCCUCAACGUGAAGCACUA.

Cell Culture

MDA-MB-231, Cal51, MCF-7, NIH3T3, HEK293, and HEK293FT cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS. T47D cells were cultured in RMPI-1640 containing 10% FBS. SUM159 and SUM1315 cells were cultured in Ham's F-12 supplemented with 5% FCS. All cells were grown at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Transfection or Lentiviral Infection

For siRNA-mediated knockdown of gene expression, LipofectamineRNAiMAX (Invitrogen) was used following the protocol provided by manufacturer, and cells were used 48–72 h post-transfection. For transient transfection into HEK293 cells, Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used. Cells were harvested 24 h post-transfection. For the expression or co-expression of genes into MDA-MB-231 or NIH3T3, a lentiviral system was used as described previously (22). Cells were harvested 48 h postinfection (70–80% of infection efficiency was achieved for the experiments).

Stimulation in Suspension Condition

For the stimulation of cells in the suspension condition, cells were serum-starved overnight, followed by trypsinization and resuspension of cells in serum-free DMEM containing 0.2% BSA. Cells were incubated for 1–2 h in a CO2 incubator before stimulating with FBS (2.5–5% FBS) or EGF (1–10 ηg/ml) or ECM protein (combination of fibronectin/collagen type I, 25 μg/ml each) for the indicated time periods. “Suspension condition” refers to the cells resuspended in their corresponding medium containing 0.2% BSA and 0.5% FBS after trypsinization/detachment. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in an incubator for 2–3 h except for in the time course study. For overnight culture in suspension condition, cells suspended in the medium were seeded into the culture plate coated with 0.3% agar to avoid cell attachment and incubated in a CO2 incubator.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed using lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm NaF, 5 mm Na3VO4, and protease inhibitors). Clear supernatants were incubated with the indicated antibodies for 3–4 h to overnight at 4 °C, followed by isolation of immunocomplexes using protein G-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Biosciences). Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer before eluting the immunocomplexes with 2× sample buffer and then subjected to immunoblotting using specific antibodies.

Anchorage-independent Growth

For anchorage-independent growth, cells were suspended into the medium containing 0.3% agar and seeded into 24-well culture plates (18). To avoid cell attachment, culture plates were precoated with 0.5% agar before cell seeding. Cultures were fed with fresh medium in every 3–5 days and cultured for 1–3 weeks. For inhibition of Akt signaling, PI3K inhibitor (LY294002, 10 μm) was added into the medium. Colonies developed were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet to facilitate the visualization and counting of colonies.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

For the immunofluorescence study, colonies developed in the soft agar were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde, followed by cell permeabilization with 0.1% Triton-X and blocking with 3% BSA in PBS. Cells were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with Alexa555- and/or Alexa488-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were mounted using Vectashield and visualized with a Nikon TE2000-U microscope. Images were acquired using MetaMorph and processed using Adobe Photoshop.

Protein-Lipid Overlay Assay

The effect of PIPKIγ knockdown or PIPKIγi2 overexpression on cellular level of PIP2 and PIP3 were examined by a protein-lipid overlay assay (23). Briefly, acidic lipids containing PIP2 and PIP3 were isolated from unstimulated or stimulated cells following the protocol provided by Echelon Biosciences. Equal numbers of cells were used for the lipid extraction (5 × 105 cells for PIP2 and 10 × 106 for PIP3). Isolated lipids were dissolved into MeOH·CHCl3·HCl and spotted onto nitrocellulose membrane, followed by blocking with 3% BSA in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T). Membranes were incubated with GST-PLCδ-PH (0.5 μg/ml; Echelon Biosciences) or GST-GRP1-PH (1 μg/ml; Echelon Biosciences) overnight at 4 °C. The bound proteins with the lipids in the membrane were detected using HRP-labeled anti-GST antibody (Sigma). The signals generated were measured by the ImageJ program (National Institutes of Health).

Statistical Analysis

The data are presented mean ± S.D. from at least three independent experiments. An unpaired t test was conducted to determine the p value and the statistical significance between two groups (p < 0.05 was considered significant).

Results

PIPKIγ Is Required for PI3K/Akt Activation

The role of individual PIPKI enzymes was investigated in Akt activation in response to FBS or ECM protein stimulation. Cells were stimulated in suspension because this facilitated the segregation of PI3K/Akt signaling initiated in response to growth factors versus ECM proteins. These conditions are also relevant to metastasizing tumor cells in the vasculature or lymphatic circulation as well as circulating tumor cells found in cancer patients (24, 25).

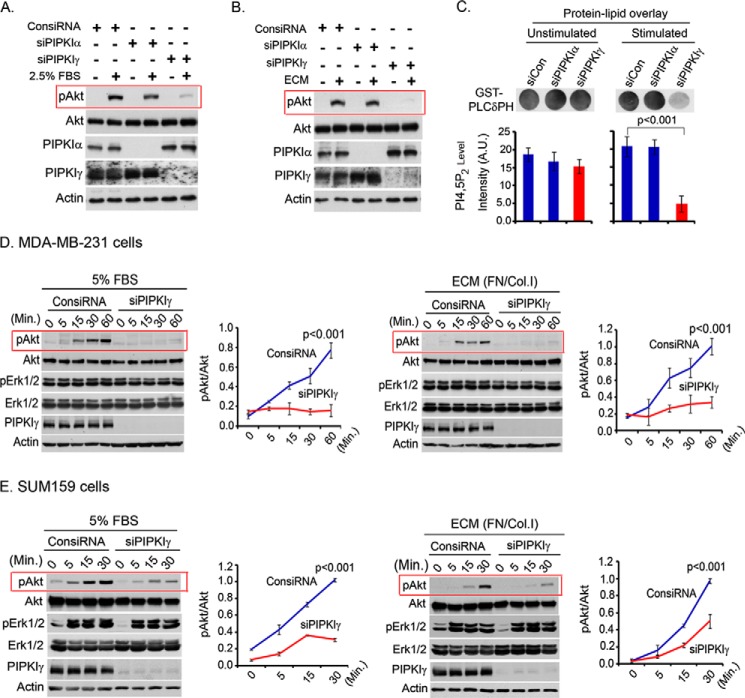

Specific siRNA was used to knock down individual PIPKI isoforms from MDA-MB-231 or other cell lines. The knockdown of PIPKIγ impaired Akt activation in response to both FBS and ECM protein stimulation of the cells (Fig. 1, A and B). This is consistent with the PIPKIγ function in organizing the signaling complex at the plasma membrane and in PIP2 synthesis, the PI3K substrate for PIP3 generation and Akt activation. The knockdown of PIPKIα in comparison showed little impact on Akt activation, demonstrating specificity for PIPKIγ. The impaired activation level of PI3K/Akt was correlated with a significantly decreased PIP2 level in PIPKIγ knockdown cells upon stimulation with FBS and ECM protein in suspension condition (Fig. 1C). Because PIPKIγ is overexpressed in triple-negative breast cancer tissues and plays a role in anchorage-independent growth of tumor cells (18, 26), its role in PI3K/Akt signaling was further examined. The effect of PIPKIγ knockdown on the time course of Akt activation after FBS or ECM stimulation of MDA-MB-231 cells was examined (Fig. 1D). Similar results were obtained in a number of different cell lines, including SUM159 and SUM1315 (Fig. 1E) (data not shown). Furthermore, the effect of PIPKIγ knockdown was more specific toward PI3K/Akt activation because the phosphorylation level of Erk1/2 was minimally affected. However, we could not investigate the effect of PIPKIγ knockdown on Erk1/2 activation in MDA-MB-231 cells because Erk1/2 is constitutively active in this cell line (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

PIPKIγ knockdown blocked Akt activation upon FBS or ECM stimulation. A and B, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with isoform-specific siRNA for PIPKI knockdown. 48 h post-transfection, cells were serum-starved overnight and resuspended into the serum-free medium. Cells were stimulated with FBS (A) or ECM protein (B) for 10 min in the suspension condition. Activated Akt was examined by immunoblotting using phospho-specific antibody for activated Akt. C, PIP2 level in the cells was examined by a protein-lipid overlay assay. Acidic lipids were isolated from an equal number of cells as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The isolated lipids were spotted into the nitrocellulose membrane before incubating with purified GST-PLCδPH protein. HRP-labeled anti-GST antibody was used to detect the bound GST-PLCδPH. A.U., arbitrary units. D, siRNA was used to knock down PIPKIγ expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. As described above, cells were stimulated with FBS or ECM for different time periods before examining the activated Akt and Erk1/2 by immunoblotting. The same experiments were repeated using SUM159 cells (E). Results are represented as means ± S.D. (error bars) from three independent experiments.

PIPKIγ Knockdown Impaired Persistent PI3K/Akt Signaling

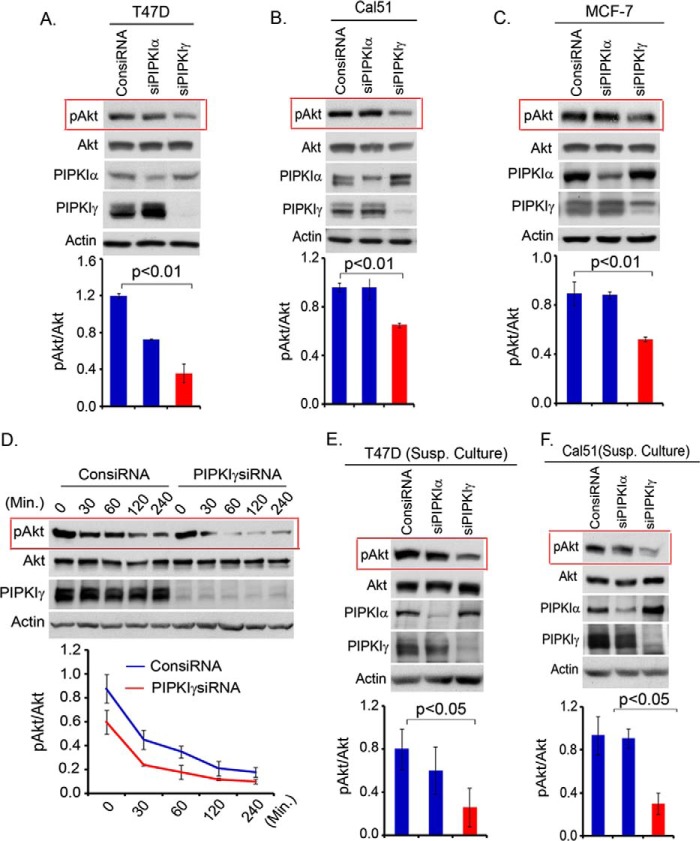

Persistent Akt activation is a key mechanism in oncogenic growth regulation (2, 4). The role of different PIPKI enzymes in protracted PI3K/Akt signaling was examined in different tumor cell lines, including T47D, Cal51, and MCF-7, that show constitutive and higher activation levels of PI3K/Akt signaling due to mutation in the p110α catalytic subunit of the PI3K enzyme (27, 28). As shown in Fig. 2, A–C, the activation level of Akt maintained in T47D, Cal51, and MCF-7 cells growing in normal growth medium was diminished upon PIPKIγ knockdown. Similarly, the knockdown of PIPKIγ in T47D cells significantly abrogated the strength and duration of Akt activation upon withdrawal of serum-containing medium (Fig. 2D). Similar to the adherent condition, these cells maintained a higher level of activated Akt in the suspension condition, which plays a critical role in the oncogenic growth regulation of these tumor cells. As shown in Fig. 2, E and F, PIPKIγ knockdown significantly abrogated the activation level of Akt in the suspension culture of T47D and Cal51 cells and is consistent with the impaired anchorage-independent growth of these tumor cells upon PIPKIγ loss (18).

FIGURE 2.

Persistence of PI3K/Akt signaling is impaired upon the loss of PIPKIγ. A–C, isoform-specific siRNA were used to knock down PIPKI expression in T47D, Cal51, and MCF-7 cells. Cells were harvested 48–72 post-transfection to examine the activated Akt level by immunoblotting. D, T47D cells after siRNA transfection for PIPKIγ knockdown in the adherent condition were incubated in serum free-medium for different time periods before examining the activation level of Akt by immunoblotting. E and F, isoform-specific siRNA was used to knockdown PIPKI expression in T47D and Cal51 cells. 48 h post-transfection, cells were resuspended and cultured in the suspension condition by seeding the cells into culture plates precoated with soft agar. Cells were harvested 1–2 days later to examine the activation level of Akt in suspension culture. Results are represented as mean ± S.D. (error bars) from three independent experiments.

The Loss of PIPKIγi2 Mimics the Loss of PIPKIγ on PI3K/Akt Activation

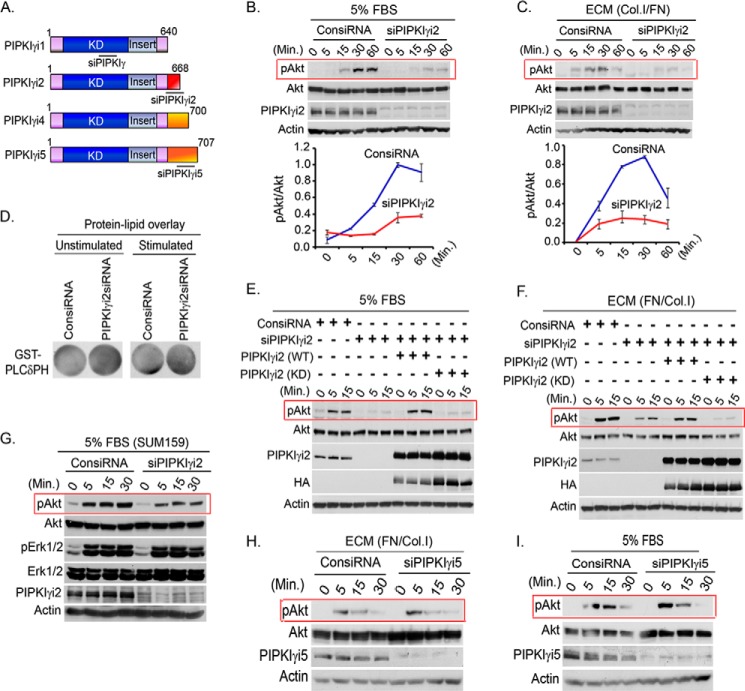

Previously, we have shown that PIPKIγi2 and Src control anchorage-independent growth of tumor cells (18). The role of PIPKIγi2, a focal adhesion-targeting variant of PIPKIγ (for a schematic diagram of PIPKIγ variants, see Fig. 3A), was investigated with the hypothesis that it plays a major role in the spatial synthesis of PIP2 required for PIP3 generation in response to growth factor receptor and adhesion receptor activation, consistent with the compartmentalization of cellular signaling (6, 29). As shown in Fig. 3, B and C, the knockdown of PIPKIγi2 recapitulated the effect of PIPKIγ knockdown on PI3K/Akt activation. However, unlike the knockdown of pan-PIPKIγ, the knockdown of the PIPKIγi2 variant did not show any obvious decrease in the PIP2 level (Fig. 3D), indicating that the effect of PIPKIγi2 may result from localized changes in PIP2 and PIP3 levels in the vicinity of activated growth factor and adhesion receptors in the plasma membrane. Furthermore, kinase activity of PIPKIγi2 was required for rescuing the defect on Akt activation in PIPKIγi2 knockdown cells (Fig. 3, E and F). The effect of PIPKIγi2 knockdown was more specific toward PI3K/Akt activation because the phosphorylation level of Erk1/2 was minimally affected in SUM159 and SUM1315 cells (Fig. 3G) (data not shown). Furthermore, the knockdown of PIPKIγi5, an endosomal targeting variant of PIPKIγ, showed no effect on Akt activation when stimulated with ECM protein and FBS in the suspension condition (Fig. 3, H and I). These results are also consistent with the role of PIPKIγi2 in PIP2 synthesis required for the assembly of the adhesion complex at the plasma membrane (13, 30).

FIGURE 3.

PIPKIγi2 knockdown impaired PI3K/Akt signaling. A, schematic diagram of PIPKIγ variants and target sites for the siRNA used are indicated. B and C, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with siRNA specific for PIPKIγi2. 48–72 h post-transfection, cells were serum-starved overnight and resuspended into serum-free medium before stimulating with FBS or ECM for different time periods. The activation level of Akt was examined by immunoblotting using phospho-specific antibody as described above. D, PIP2 level in the cells was examined by protein-lipid overlay assay as described above. E and F, endogenous PIPKIγi2 was silenced using siRNA from MDA-MB-231 cells or MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing siRNA-resistant PIPKIγi2 (WT) or its kinase dead mutant, PIPKIγi2 (KD). Cells were stimulated with FBS and ECM protein as described above before examining the activated Akt. G, siRNA was used to knockdown PIPKIγi2 in SUM159 cells before examining its effect on the activation level of Akt and Erk1/2 upon stimulation with FBS as described above. H and I, MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with siRNA specific for PIPKIγi5 were stimulated with FBS and ECM protein as described above, and the activation level of Akt was examined as described above.

PIPKIγi2 Overexpression Induces PI3K/Akt Activation and Oncogenic Growth

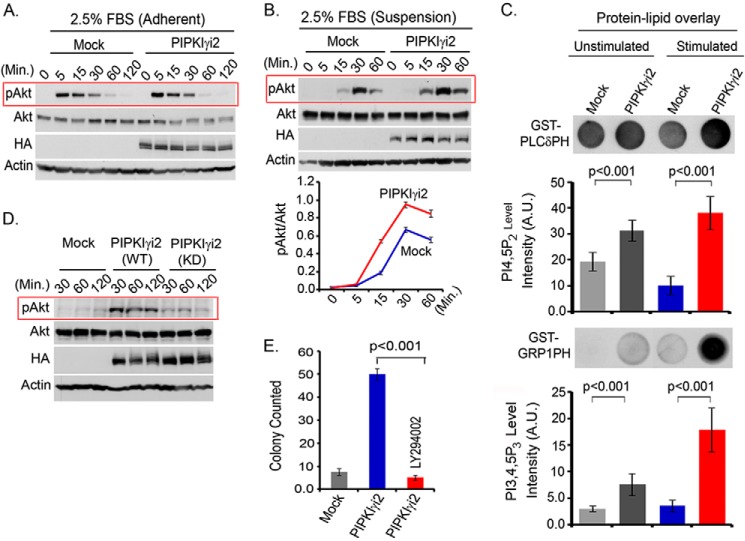

PIPKIγ is overexpressed in triple-negative breast cancers, but the expression of different splices variants remains undefined (26). The impact of overexpression of PIPKIγ variants on Akt activation was examined using MDA-MB-231 cells. In the adherent condition, the loss or overexpression of PIPKIγi2 or other variants showed minimal effect on Akt activation in response to FBS stimulation (Fig. 4A). However, in the suspension condition, PIPKIγi2-overexpressing cells showed a modest increase in Akt activation in response to FBS and ECM protein stimulation of the cells (Fig. 4B) (data not shown). Analysis of phosphoinositide contents in the cells indicated a significantly increased PIP2 level in PIPKIγi2-overexpressing cells, which was further increased upon cell activation (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the increased level of activated Akt, we observed a significantly increased level of PIP3 level in PIPKIγi2-overexpressing cells. This indicates that PIP2 generated by PIPKIγi2 is associated with PIP3 synthesis, leading to PI3K/Akt activation in the plasma membrane. Furthermore, PIPKIγi2-overexpressing cells maintained the higher level of activated Akt following the disruption of the cell-matrix interaction and incubation in the suspension condition (Fig. 4D), which also corroborates with its anchorage-independent growth-promoting effect (18).

FIGURE 4.

PIPKIγi2 overexpression promotes PI3K/Akt signaling and oncogenic growth. A and B, mock or PIPKIγi2-overexpressing cells were stimulated with FBS in the adherent (A) or suspension (B) condition as described above, and activated Akt was examined by immunoblotting. C, acidic lipids were isolated from an equal number of mock or PIPKIγi2-overexpressing cells in both non-stimulated and stimulated conditions (10 min after stimulation with FBS and ECM protein) and spotted into the nitrocellulose membrane before incubating with purified GST-PLCδPH or GST-GRP1PH proteins. HRP-labeled anti-GST antibody was used to detect the proteins bound to lipids in the membrane. A.U., arbitrary units. D, subconfluent culture of MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing PIPKIγi2 or its kinase-dead mutant was trypsinized and resuspended into the low FBS-containing medium. Cells were incubated in the suspension condition before harvesting the cells at different time points. The activated Akt was examined by immunoblotting. E, MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing PIPKIγi2 were cultured in soft agar in the presence or absence of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 μm). The colonies formed were counted after 2–3 weeks. Results are represented as mean ± S.D. (error bars) from three independent experiments.

After demonstrating the role of PIPKIγi2 in PI3K/Akt signaling, the role of PI3K/Akt signaling in oncogenic growth regulation by PIPKIγi2 was investigated. The PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, was used to block PI3K/Akt signaling in MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing PIPKIγi2. As expected, the LY294002 compound significantly impaired the anchorage-independent growth induced by the PIPKIγi2 expression (Fig. 4E). Anchorage-independent growth is one of the most commonly utilized in vitro methods to define cell transformation/oncogenic growth that directly correlate with in vivo tumor growth and metastasis (31, 32).

PIPKIγi2 and Src Cooperate to Regulate PI3K/Akt Signaling

PIPKIγi2 interacts with Src, and they collaboratively control anchorage-independent growth of tumor cells (18). Src is rapidly recruited to a wide spectrum of growth factor receptors and adhesion molecules and controls the oncogenic growth of tumor cells by regulating downstream signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt signaling (33–35). Similarly, Src phosphorylation of PIPKIγi2 regulates its interaction with the cytoskeletal protein, talin, which mediates its recruitment to the integrin-mediated adhesion complex (17, 18). The direct association of PIPKIγi2 with talin and Src may facilitate its recruitment/assembly in the proximity of activated growth factor receptors and integrin-mediated adhesion complex in the plasma membrane to synthesize the spatial pool of PIP2 for PIP3 generation and Akt activation.

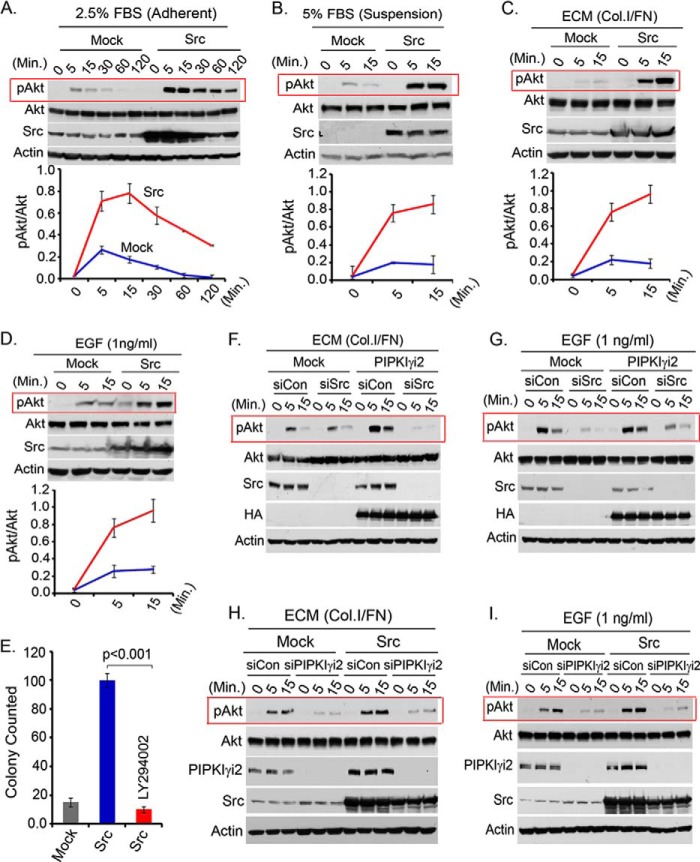

A number of studies demonstrate Src regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling via diverse mechanisms (36–42). Ectopic expression of Src promoted PI3K/Akt activation in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5A). Consistently, in the suspension condition, Src-expressing cells rapidly induced Akt activation in response to FBS, ECM protein, and EGF stimulation (Fig. 5, B–D). These cells also showed persistent Akt activation in a low FBS-containing medium (not shown). Furthermore, the inhibition of PI3K by LY294002 significantly impaired the anchorage-independent growth of Src-expressing cells (Fig. 5E), indicating the role of PI3K/Akt signaling in the oncogenic growth regulation of Src.

FIGURE 5.

PIPKIγi2 and Src cooperate to regulate PI3K/Akt signaling. A and B, mock or Src-expressing MDA-MB-231 cells after overnight serum starvation were stimulated with FBS in the adherent condition (A) or in the suspension condition (B) for different time periods. Cells were harvested, and activated Akt was examined by immunoblotting. C and D, mock or Src-expressing MDA-MB-231 cells were stimulated with ECM protein or EGF in the suspension condition before examining the activated Akt. E, MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing Src were cultured in soft agar in the presence or absence of PI3K inhibitor, LY294002 (10 μm). After 2–3 weeks, the colonies formed were counted. F and G, siRNA was used to knock down Src from PIPKIγi2-overexpressing MDA-MB-231 cells. Then the effect of Src knockdown in Akt activation upon ECM and EGF stimulation in the suspension condition was examined as described above. H and I, PIPKIγi2 was knocked down from Src-overexpressing cells using siRNA. Its effect on Akt activation in response to ECM protein and EGF stimulation of cells in the suspension condition was examined as described above. Results are represented as mean ± S.D. (error bars) from three independent experiments.

The role of Src and PIPKIγi2 in Akt activation in PIPKIγi2-overexpressing cells was investigated. Src interacts with PIPKIγi2, and Src knockdown severely impaired the anchorage-independent growth of PIPKIγi2-overexpressing cells (18). As shown in Fig. 5, F and G, the knockdown of Src abrogated Akt activation in PIPKIγi2-overexpressing MDA-MB-231 cells. These results indicate that PIPKIγ/PIPKIγi2 functions together with Src in the regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling, which supports their role in the organization of signaling complexes and their co-targeting to plasma membrane/adhesion complexes along with the PI3K enzyme.

After demonstrating the role of Src in PI3K/Akt signaling, siRNA was used to knockdown PIPKIγi2 from Src-transfected cells, with the aim of determining whether Src recruits and/or collaborates with PIPKIγi2 in the regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling. As shown in Fig. 5, H and I, PIPKIγi2 knockdown significantly impaired Akt activation in Src-expressing cells stimulated with ECM protein and growth factor (e.g. EGF). These results are also consistent with previous findings that PIPKIγi2 regulated Src activation downstream of the growth factor receptor and integrins (18) and indicate the cooperative role of PIPKIγi2 and Src in the regulation of both signaling and function.

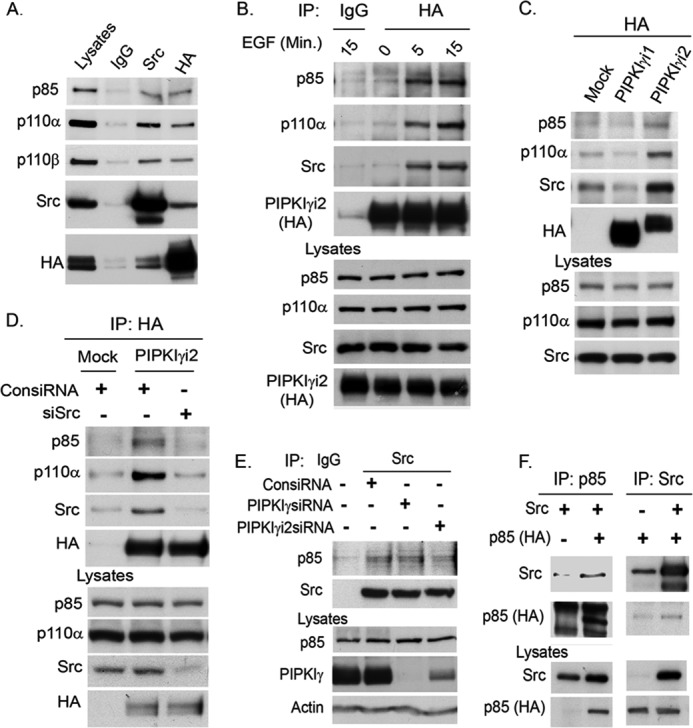

PIPKIγi2 Forms a Signaling Complex with Src and PI3K

To define a mechanism for PIPKIγi2 regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling, we investigated whether the PIPKIγi2 and PI3K enzymes are integrated into a complex upon cell stimulation. PIPKI enzymes often assemble into complexes, where the PIP2 generated modulates an effector molecule (5, 6, 9). In this case, the proximity of PIPKIγi2 and PI3K may facilitate the generation of the spatial pool of PIP2 that is used by PI3K for generation of the PIP3 that then activates Akt. PI3K utilizes SH2 domains of the p85 adaptor subunit for its recruitment to tyrosine-phosphorylated motifs of activated receptors (2). Similarly, PIPKIγi2 may utilize its direct interacting partners, Src and talin, in its recruitment to the proximity of activated growth factor receptors or adhesion complexes.

The incorporation of PIPKIγi2, Src, and PI3K enzymes into a complex was examined in MDA-MB-231 cells ectopically expressing PIPKIγi2 and Src (Fig. 6A). The assembly of these complexes was induced by activated growth factors and adhesion receptors, as demonstrated by the increased association of PIPKIγi2 with Src and PI3K in the cells stimulated with EGF and ECM protein (fibronectin/collagen type I) (Fig. 6B). The interaction of PIPKIγi2 with PI3K was specific because PIPKIγi1, which is deficient in focal adhesion targeting and talin binding, did not integrate into the complex (Fig. 6C). Most significantly, Src knockdown severely impaired PIPKIγi2 association with PI3K (Fig. 6D). The loss of PIPKIγ or PIPKIγi2 did not affect the Src association with PI3K (Fig. 6E). The co-expression and coimmunoprecipitation study demonstrated Src association with PI3K (Fig. 6F) and is consistent with reported studies (38, 42). All of these results indicate that Src functions as a bridging molecule in incorporating both PIPKIγi2 and PI3K into a complex. This provides the mechanism for the spatial generation of PIP2 and PIP3 for Akt activation upon growth factor and adhesion receptor activation.

FIGURE 6.

Src promotes the integration of PIPKIγi2 and PI3K into a complex. A, PIPKIγi2 or Src was immunoprecipitated from MDA-MB-231 cells co-expressing PIPKIγi2 and Src. The coimmunoprecipitation of PI3K enzyme into the immunocomplex was examined by immunoblotting using the antibody specific for PI3K subunits (e.g. p85 and p110α). B, MDA-MB-231 cells expressing PIPKIγi2 were incubated in the suspension condition or stimulated with EGF and ECM for the indicated time periods. PIPKIγi2 was immunoprecipitated, and coimmunoprecipitation of Src and PI3K into the immunocomplex was examined by immunoblotting. C, MDA-MB-231 cells expressing PIPKIγi1 or PIPKIγi2 were stimulated with EGF and ECM protein in the suspension condition as described above. Then PIPKIγi1 or PIPKIγi2 was immunoprecipitated to examine the coimmunoprecipitation of Src and PI3K into the immunocomplex. D, PIPKIγi2 was immunoprecipitated from MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with siRNA for the knockdown of Src. Cells were stimulated as described above, and the coimmunoprecipitation of PI3K with PIPKIγi2 in the immunocomplex was examined by immunoblotting. E, endogenous Src was immunoprecipitated from HEK293 cells transfected with siRNA for PIPKIγ or PIPKIγi2 knockdown. The coimmunoprecipitation of PI3K with Src was examined by immunoblotting. F, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with Src and p85. Src was immunoprecipitated, and coimmunoprecipitation of p85 was examined by immunoblotting. Reciprocally, coimmunoprecipitation of Src with p85 was examined.

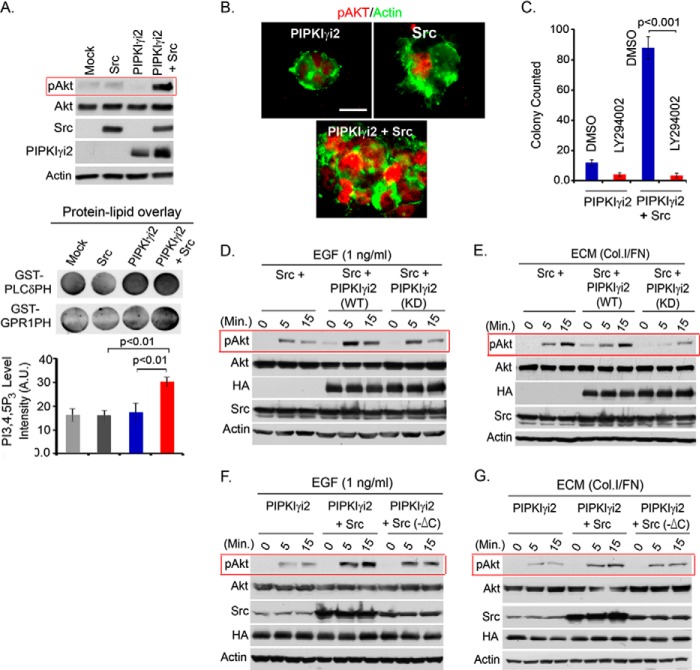

Co-expression of PIPKIγi2 and Src Induces PI3K/Akt Activation and Anchorage-independent Growth

Previously, the synergistic role for PIPKIγi2 and Src in anchorage-independent growth regulation was demonstrated (18). Corroborating these results, co-expression of PIPKIγi2 and Src induced a dramatic and synergistic increase in Akt activation in suspension culture (Fig. 7A). This was further validated by demonstrating the significantly increased PIP3 level in the cells co-expressing PIPKIγi2 and Src (Fig. 7A, bottom). Furthermore, the colonies developed by PIPKIγi2- and Src-expressing cells in the soft agar also showed increased immunostaining for phosphorylated Akt (Fig. 7B). The PI3K/Akt signaling was required for increased anchorage-independent growth in PIPKIγi2- and Src-expressing cells because the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 significantly abrogated colonies developed by these cells in soft agar (Fig. 7C), establishing the role for PI3K/Akt signaling in PIPKIγi2 and Src regulation of oncogenic growth. Corroborating this, the knockdown of Src and PIPKIγi2 impaired PI3K/Akt signaling in T47D and HCC1954 cells in suspension culture (data not shown). Furthermore, a kinase-dead mutant of PIPKIγi2 (D253A,D316A) was severely impaired in inducing PI3K/Akt activation in concert with Src upon stimulation of cells with growth factor and ECM protein (Fig. 7, D and E). This indicates that kinase activity of PIPKIγi2 and PIP2 generation is required for PI3K/Akt signaling. The interaction between PIPKIγi2 and Src was also required for induced Akt activation and oncogenic growth because the Src mutant deficient in PIPKIγi2 binding was significantly impaired in inducing Akt activation (Fig. 7, F and G) and anchorage-independent growth in synergy with PIPKIγi2, as indicated previously (18). This was further substantiated by the disruption of the PIPKIγi2 and Src interaction by the C terminus of Src, which inhibited Akt activation induced by the co-expression of PIPKIγi2 and Src (data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

Co-expression of PIPKIγi2 and Src induces Akt activation and oncogenic growth. A, PIPKIγi2 and Src were individually expressed or co-expressed into MDA-MB-231 cells. These cells were resuspended and cultured in the suspension condition for 1–2 days before harvesting the cells. Activated Akt was examined by immunoblotting. Similarly, lipids were extracted from these cells after 4–5 h of incubation in the suspension condition as described above. Lipids were spotted into the nitrocellulose membrane before incubating with purified GST-PLCδ-PH or GST-GRP1-PH protein. HRP-labeled anti-GST antibody was used to detect the proteins bound to lipids in the membrane. A.U., arbitrary units. B, colony developed by MDA-MB-231 cells individually expressing PIPKIγi2 and Src or co-expressing both of them was immunostained using antibody for activated Akt (red) and actin (green). Bar, 10 μm. C, anchorage-independent growth of MDA-MB-231 cells co-expressing PIPKIγi2 and Src was examined in the presence or absence of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002. Colonies formed were counted after 2 weeks of culture in soft agar as described previously. D and E, MDA-MB-231 cells expressing Src or co-expressing Src with PIPKIγi2 or its kinase-dead mutant were stimulated with EGF and ECM protein in the suspension condition before examining the activated Akt by immunoblotting. F and G, MDA-MB-231 cells expressing PIPKIγi2 or co-expressing PIPKIγi2 with wild type Src or C-terminal deletion mutant, Src (-ΔC) deficient in PIPKIγi2 binding were stimulated with EGF and ECM protein in the suspension condition before examining the activated Akt.

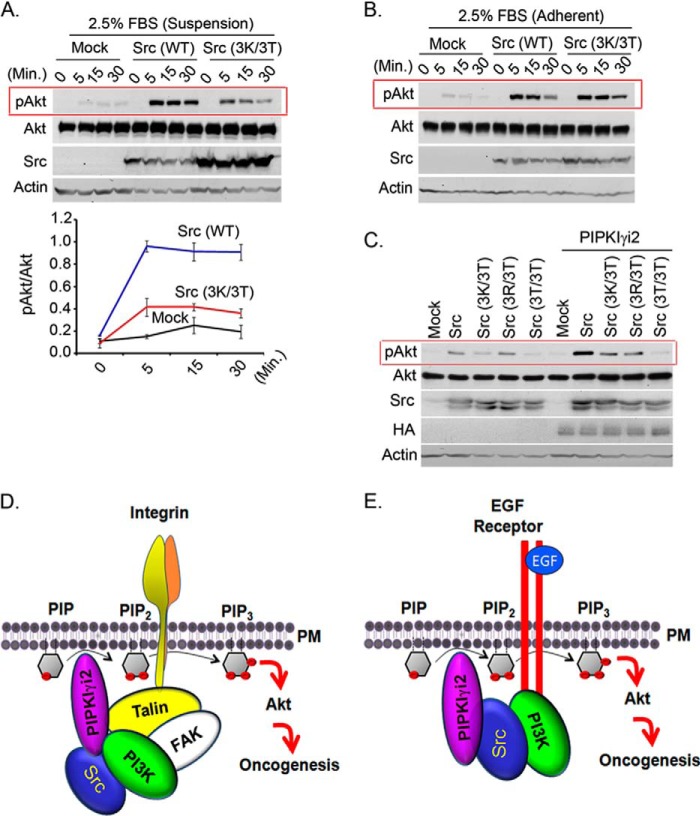

Src contains highly conserved basic residues at the N terminus that are potential anionic phospholipid binding sites, and these residues play a crucial role in Src recruitment and its activation in the plasma membrane (18, 43, 44). The Src mutant, Src (3K/3T) (lysine residues mutated to threonine) poorly induced Akt activation in response to FBS stimulation in the suspension condition (Fig. 8A), although it was competent in the adherent condition (Fig. 8B). Consistently, this mutant showed impaired Akt activation in synergy with PIPKIγi2 in the suspension culture (Fig. 8C). This is consistent with the Src mutants' impaired ability to induce anchorage-independent growth in collaboration with PIPKIγi2 (18). This indicates that Src association with the PIPKIγi2 and PIP2 generated also regulates Src function and is also consistent with our previous results that PIPKIγi2 knockdown affects Src activation downstream of EGF receptors (18). With these results, we conclude that PIPKIγi2 regulates PI3K/Akt signaling and oncogenic growth in coordination with the proto-oncogene Src.

FIGURE 8.

Highly conserved basic amino acids residues in the N terminus of Src are required for Akt activation in synergy with PIPKIγi2. A and B, MDA-MB-231 cells expressing wild type or its mutant form of Src were stimulated in suspension (A) or adherent condition (B) with FBS before examining the activated Akt by immunoblotting. C, NIH3T3 cells co-expressing Src or its mutant form with PIPKIγi2 were cultured in suspension condition for 1–2 days before examining the activated Akt by immunoblotting. D and E, schematic diagram depicting the role of PIPKIγi2 and Src in regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling. PIPKIγi2 is recruited at the vicinity of activated integrins via talin, its direct interacting partner, whereas PI3K can utilize focal adhesion kinase for its recruitment at the adhesion complex upon integrin activation. Simultaneous recruitment of PIP2- and PIP3-synthesizing enzyme may provide the spatial pool of PIP2 and PIP3 required for Akt recruitment to plasma membrane and its subsequent activation, which supports oncogenic growth of tumor cells. Similarly, PIPKIγi2 is recruited in proximity to activated growth factor via Src, which directly interacts with phosphorylated tyrosine motifs of activated growth factor receptors (E). PI3K recognizes distinct tyrosine motifs of activated growth factor receptors. Thus, PIPKIγi2 represents the candidate molecule to contribute the spatial pool of PIP2 required for PIP3 generation and Akt activation upon activation of growth factor receptors and integrins, which promotes oncogenic growth signaling in tumor cells.

Discussion

PI3K/Akt signaling is one of the most commonly deregulated signaling pathways in cancer and plays a key role in oncogenic growth signaling (2, 3). Herein, we illustrated the mechanism by which cancer cells can activate and sustain the PI3K/Akt signaling downstream of growth factor and adhesion receptors in the suspension condition. PIPKIγ and its focal adhesion targeting variant, PIPKIγi2, appeared to provide PIP2 spatially for PIP3 generation and the activation of PI3K/Akt signaling downstream of activated growth factor and adhesion receptors. This indicates that cancer cells maintain their vital cellular signaling, such as PI3K/Akt, irrespective of adherent or suspension condition. This may provide the mechanism by which metastasizing and circulating tumor cells can sustain cellular signaling for their survival and growth.

PIP2 is utilized by PI3K and PLC enzymes to generate the second messengers: PIP3, inositol triphosphate, and diacylglycerol, in response to growth factor and adhesion receptor activation (45–47). Despite these key functions, the content of PIP2 is maintained relatively constant (5, 6, 9). This indicates that PIP2 synthesis may be channeled for use as a messenger or a precursor for messenger generation (5, 6, 46). Here we show that the PIP2-synthesizing enzyme PIPKIγi2 regulated by Src is integrated into a PI3K complex that is required for the activation of PI3K/Akt signaling. The PI3K-mediated conversion of PIP2 into PIP3 is required for the activation of Akt. Our results support a model where PIPKIγi2-generated PIP2 is utilized by PI3K to synthesize PIP3 and activate Akt. The PI3K/Akt signaling nexuses have roles in oncogenesis (2), and the PIPKIγi2 is required for this pathway in the suspension condition and for anchorage-independent growth of the tumor cells (18). Among different isoforms of PIPKI enzymes, the knockdown of PIPKIγ, which is overexpressed in breast cancer and correlates with poor patient prognosis (26), showed specificity for PI3K/Akt signaling in the suspension condition. The focal adhesion targeting variant, PIPKIγi2, recapitulated the outcome of PIPKIγ knockdown on Akt activation.

The assembly of the signaling complex is the primary event in the initiation and transduction of intracellular signals (48, 49). Many signaling proteins are targeted to the activated growth factor receptors and integrins in the plasma membrane via their SH2 or phosphotyrosine binding domain or similar domains (48, 49). The PI3K enzyme is rapidly recruited to the plasma membrane by utilizing the SH2 domain-mediated interaction of its adaptor subunit (e.g. p85) with phosphotyrosine residues of activated growth factor receptors (2, 3). Upon cell stimulation, PIPKIγi2 specifically associated with Src and the PI3K enzyme; Src facilitated the assembly of the complex of PIPKIγi2 and PI3K as Src knockdown impaired PI3K/Akt activation in PIPKIγi2-expressing cells as well as PIPKIγi2 assembly into the complex. Further, PIPKIγi2 (of the six different PIPKIγ variants) is targeted to the cell-ECM interface via interaction with the cytoskeletal protein, talin (13, 30), positioning PIPKIγi2 as a key enzyme synthesizing PIP2 in response to cell stimulation with ECM proteins through integrin activation. These concepts are supported by (i) impaired Akt activation by PIPKIγi2 knockdown, (ii) increased PIP2 and PIP3 levels in PIPKIγi2-overexpressing cells, and (iii) specific incorporation of PIPKIγi2 with the PI3K enzyme upon cell stimulation with growth factors and ECM protein. This supports a model in which the PIPKIγi2-generated pool of PIP2 is utilized by the PI3K to generate PIP3 for Akt activation (Fig. 8, D and E). Phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the C terminus of PIPKIγi2 by Src (17) could also regulate interaction between PIPKIγi2 and PI3K enzyme, thus promoting the co-targeting of both PIP2- and PIP3-generating enzymes to the plasma membrane to facilitate PI3K/Akt signaling. These interactions may define the fundamental basis of PI3K/Akt regulation by the PIP2-synthesizing enzyme in response to some cell stimuli.

Src, a cytosolic tyrosine kinase, is activated downstream of many growth factor receptors, cytokine receptors, and adhesion receptors (34, 50, 51). By virtue of its SH2 and SH3 domains, Src interacts with different signaling molecules and modulates their functionality (34, 51). Along with its own defined sets of downstream signaling cascades, Src regulates PI3K/Akt signaling by different mechanisms. Some of these include phosphorylation of adaptor subunits of PI3K (e.g. Tyr-688 on p85) and alleviation of inhibitory constraints to its catalytic subunit, p110α (39); co-targeting with PI3K to activated growth factor receptors (38); and activation of Ras and inactivation of PTEN (37), a negative regulator of PI3K/Akt signaling. Here, we show that Src facilitates the assembly of the PIP2-synthesizing enzyme, PIPKIγi2, in the proximity of activated receptors and adhesion complex to support PI3K/Akt activation required for the oncogenic growth of tumor cells. This is consistent with many studies indicating that PI3K/Akt activation is the cumulative outcome of several pathways (2).

With these results, we conclude that PIPKIγi2 coordinates with Src and possibly talin for spatial assembly with PI3K in the proximity of activated growth factor receptors and adhesion complexes for PIP2 and PIP3 synthesis for Akt activation even in the suspension condition (Fig. 8, D and E). This could represent a signaling nexus required for the survival and growth of metastasizing and circulating tumor cells in vivo and is also consistent with reported studies that have demonstrated the role of PIPKIγ/PIPKIγi2 in oncogenic growth and tumor metastasis (18, 19, 26). Because generation of PIP3 by PI3K and Akt activation has significant therapeutic implications for cancers, targeting PIPKIγ/PIPKIγi2 could pave the way for controlling the PI3K/Akt signaling nexus in metastasizing and circulating tumor cells in vivo.

Author Contributions

N. T. and R. A. A. conceived the idea. N. T., S. C., X. T., and T. W. performed the experiments. N. T. and R. A. A. wrote the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA104708 and GM057549 (to R. A. A). This work was also supported by American Heart Association Grants 10POST4290052 (to N. T.) and 13PRE14690057 (to S. C.) and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research Fellowship (to X. T.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- ECM

- extracellular matrix protein

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- SH2

- Src homology domain 2

- SH3

- Src homology domain 3

- PIP2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-phosphate

- PIP3

- phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate

- PIPKI

- phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase

- PTEN

- phosphatase and tensin homolog.

References

- 1. Croce C. M. (2008) Oncogenes and cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 502–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu P., Cheng H., Roberts T. M., Zhao J. J. (2009) Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 627–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bunney. T. D., Katan M. (2010) Phosphoinositide signalling in cancer: beyond PI3K and PTEN. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 342–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Samuels Y., Diaz L. A., Jr., Schmidt-Kittler O., Cummins J. M., Delong L., Cheong I., Rago C., Huso D. L., Lengauer C., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Velculescu V. E. (2005) Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell 7, 561–5673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choi S., Thapa N., Tan X., Hedman A. C., Anderson R. A. (2015) PIP kinases define PI4,5P signaling specificity by association with effectors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1851, 711–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sun Y., Thapa N., Hedman A. C., Anderson R. A. (2013) Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate: targeted production and signaling. Bioessays 35, 513–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Divecha N. (2010) Lipid kinases: charging PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis. Curr. Biol. 20, R154–R157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Balla T. (2013) Phosphoinositides: tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol. Rev. 93, 1019–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heck J. N., Mellman D. L., Ling K., Sun Y., Wagoner M. P., Schill N. J., Anderson R. A. (2007) A conspicuous connection: structure defines function for the phosphatidylinositol-phosphate kinase family. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42, 15–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barlow C. A., Laishram R. S., Anderson R. A. (2010) Nuclear phosphoinositides: a signaling enigma wrapped in a compartmental conundrum. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 25–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schill N. J., Anderson R. A. (2009) Two novel phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type Iγ splice variants expressed in human cells display distinctive cellular targeting. Biochem. J. 422, 473–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xia Y., Irvine R. F., Giudici M. L. (2011) Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase Iγ_v6, a new splice variant found in rodents and humans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 411, 416–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ling K., Doughman R. L., Firestone A. J., Bunce M. W., Anderson R. A. (2002) Type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase targets and regulates focal adhesions. Nature 420, 89–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li X., Zhou Q., Sunkara M., Kutys M. L., Wu Z., Rychahou P., Morris A. J., Zhu H., Evers B. M., Huang C. (2013) Ubiquitylation of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase type Iγ by HECTD1 regulates focal adhesion dynamics and cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 126, 2617–2628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu Z., Li X., Sunkara M., Spearman H., Morris A. J., Huang C. (2011) PIPKIγ regulates focal adhesion dynamics and colon cancer cell invasion. PLoS One 6, e24775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sun Y., Hedman A. C., Tan X., Schill N. J., Anderson R. A. (2013) Endosomal type Iγ PIP 5-kinase controls EGF receptor lysosomal sorting. Dev. Cell 25, 144–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ling K., Doughman R. L., Iyer V. V., Firestone A. J., Bairstow S. F., Mosher D. F., Schaller M. D., Anderson R. A. (2003) Tyrosine phosphorylation of type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase by Src regulates an integrin-talin switch. J. Cell Biol. 163, 1339–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thapa N., Choi S., Hedman A., Tan X., Anderson R. A. (2013) Phosphatidylinositol phosphate 5-kinase Iγi2 in association with Src controls anchorage-independent growth of tumor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 34707–34718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen C., Wang X., Xiong X., Liu Q., Huang Y., Xu Q., Hu J., Ge G., Ling K. (2014) Targeting type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase inhibits breast cancer metastasis. Oncogene 10.1038/onc.2014.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen H. C., Appeddu P. A., Isoda H., Guan J. L. (1996) Phosphorylation of tyrosine 397 in focal adhesion kinase is required for binding phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 26329–26334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ling K., Bairstow S. F., Carbonara C., Turbin D. A., Huntsman D. G., Anderson R. A. (2007) Type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase modulates adherens junction and E-cadherin trafficking via a direct interaction with μ 1B adaptin. J. Cell Biol. 176, 343–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thapa N., Sun Y., Schramp M., Choi S., Ling K., Anderson R. A. (2012) Phosphoinositide signaling regulates the exocyst complex and polarized integrin trafficking in directionally migrating cells. Dev. Cell 22, 116–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fayngerts S. A., Wu J., Oxley C. L., Liu X., Vourekas A., Cathopoulis T., Wang Z., Cui J., Liu S., Sun H., Lemmon M. A., Zhang L., Shi Y., Chen Y. H. (2014) TIPE3 is the transfer protein of lipid second messengers that promote cancer. Cancer Cell 26, 465–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Plaks V., Koopman C. D., Werb Z. (2013) Cancer: circulating tumor cells. Science 341, 1186–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kang Y., Pantel K. (2013) Tumor cell dissemination: emerging biological insights from animal models and cancer patients. Cancer Cell 23, 573–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sun Y., Turbin D. A., Ling K., Thapa N., Leung S., Huntsman D. G., Anderson R. A. (2010) Type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase modulates invasion and proliferation and its expression correlates with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 12, R6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lehmann B. D., Bauer J. A., Chen X., Sanders M. E., Chakravarthy A. B., Shyr Y., Pietenpol J. A. (2011) Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2750–2767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aksamitiene E., Kholodenko B. N., Kolch W., Hoek J. B., Kiyatkin A. (2010) PI3K/Akt-sensitive MEK-independent compensatory circuit of ERK activation in ER-positive PI3K-mutant T47D breast cancer cells. Cell. Signal. 22, 1369–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao X., Lowry P. R., Zhou X., Depry C., Wei Z., Wong G. W., Zhang J. (2011) PI3K/Akt signaling requires spatial compartmentalization in plasma membrane microdomains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 14509–14514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Legate K. R., Takahashi S., Bonakdar N., Fabry B., Boettiger D., Zent R., Fässler R. (2011) Integrin adhesion and force coupling are independently regulated by localized PtdIns(4,5)2 synthesis. EMBO J. 30, 4539–4553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mori S., Chang J. T., Andrechek E. R., Matsumura N., Baba T., Yao G., Kim J. W., Gatza M., Murphy S., Nevins J. R. (2009) Anchorage-independent cell growth signature identifies tumors with metastatic potential. Oncogene 28, 2796–2805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Simpson C. D., Anyiwe K., Schimmer A. D. (2008) Anoikis resistance and tumor metastasis. Cancer Lett. 272, 177–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ishizawar R., Parsons S. J. (2004) c-Src and cooperating partners in human cancer. Cancer Cell 6, 209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yeatman T. J. (2004) A renaissance for SRC. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 470–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loza-Coll M. A., Perera S., Shi W., Filmus J. (2005) A transient increase in the activity of Src-family kinases induced by cell detachment delays anoikis of intestinal epithelial cells. Oncogene 24, 1727–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jin W., Yun C., Hobbie A., Martin M. J., Sorensen P. H., Kim S. J. (2007) Cellular transformation and activation of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase-Akt cascade by the ETV6-NTRK3 chimeric tyrosine kinase requires c-Src. Cancer Res. 67, 3192–3200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lu Y., Yu Q., Liu J. H., Zhang J., Wang H., Koul D., McMurray J. S., Fang X., Yung W. K., Siminovitch K. A., Mills G. B. (2003) Src family protein-tyrosine kinases alter the function of PTEN to regulate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT cascades. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 40057–40066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fincham V. J., Brunton V. G., Frame M. C. (2000) The SH3 domain directs acto-myosin-dependent targeting of v-Src to focal adhesions via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 6518–6536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cuevas B. D., Lu Y., Mao M., Zhang J., LaPushin R., Siminovitch K., Mills G. B. (2001) Tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 relieves its inhibitory activity on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27455–27461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang X. H., Wang Q., Gerald W., Hudis C. A., Norton L., Smid M., Foekens J. A., Massagué J. (2009) Latent bone metastasis in breast cancer tied to Src-dependent survival signals. Cancer Cell 16, 67–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arcaro A., Aubert M., Espinos, del Hierro M. E., Khanzada U. K., Angelidou S., Tetley T. D., Bittermann A. G., Frame M. C., Seckl M. J. (2007) Critical role for lipid raft-associated Src kinases in activation of PI3K-Akt signalling. Cell. Signal. 19, 1081–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nozu F., Owyang C., Tsunoda Y. (2000) Involvement of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and its association with pp60src in cholecystokinin-stimulated pancreatic acinar cells. Eur J. Cell Biol. 79, 803–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sigal C. T., Zhou W., Buser C. A., McLaughlin S., Resh M. D. (1994) Amino-terminal basic residues of Src mediate membrane binding through electrostatic interaction with acidic phospholipids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 12253–12257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Silverman L., Resh M. D. (1992) Lysine residues form an integral component of a novel NH2-terminal membrane targeting motif for myristylated pp60v-src. J. Cell Biol. 119, 415–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Toker A. (1998) The synthesis and cellular roles of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10, 254–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van den Bout I., Divecha N. (2009) PIP5K-driven PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis: regulation and cellular functions. J. Cell Sci. 122, 3837–3850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Di Paolo G., De Camilli P. (2006) Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature 443, 651–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lemmon M. A. (2008) Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 99–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schlessinger J., Lemmon M. A. (2003) SH2 and PTB domains in tyrosine kinase signaling. Sci. STKE 2003, RE12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Aleshin A., Finn R. S. (2010) SRC: a century of science brought to the clinic. Neoplasia 12, 599–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Parsons S. J., Parsons J. T. (2004) Src family kinases, key regulators of signal transduction. Oncogene 23, 7906–7909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]