Abstract

Study Objectives:

Depression has been identified as the most common condition comorbid to insomnia, with findings pointing to the possibility that these disorders may be causally related to each other or may share common mechanisms. Some have suggested that comorbid insomnia and depression may have a different clinical course than either condition alone, and may thus require specific treatment procedures. In this report we examined the clinical characteristics of individuals referred to an academic sleep center who report comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression and those with symptoms of insomnia outside the context of meaningful depression, and we identified differences between these groups with regard to several cognitive-related variables.

Methods:

Logistic regression analyses examined whether past week worry, dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, and insomnia symptom-focused rumination predicted group membership.

Results:

Individuals with comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression reported more past-week worry, dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, and insomnia symptom-focused rumination, than those with symptoms of insomnia without significant depression symptoms. When including all three cognitive-related variables in our model, those with comorbid symptoms reported more severe insomnia symptom-focused rumination, even when controlling for insomnia and mental health severity, among other relevant covariates.

Conclusion:

The findings contribute to our understanding of the complex nature of comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression and the specific symptom burden experienced by those with significant depression symptoms in the presence of insomnia. The findings also highlight the need for increased clinical attention to the sleep-focused rumination reported by these patients.

Citation:

Levenson JC, Benca RM, Rumble ME. Sleep related cognitions in individuals with symptoms of insomnia and depression. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11(8):847–854.

Keywords: cognition, depression, insomnia, mood, sleep, worry, rumination

Insomnia disorder is characterized by persistent dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality, with specific complaints of difficulty falling asleep, frequent nighttime awakenings with difficulty returning to sleep, and/or awakening earlier in the morning than desired despite adequate opportunity for sleep.1–3 Insomnia disorder is also characterized by significant distress or impairment in daytime functioning as indicated by symptoms such as fatigue, daytime sleepiness, impairment in cognitive performance, and mood disturbances. Prevalence estimates of chronic insomnia vary, with 30–43% of individuals reporting at least one nighttime insomnia symptom.4–7 Most reports suggest prevalence rates of diagnostically defined chronic insomnia disorder around 5–15%,6–9 though at least one has cited rates up to 22%, when using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria to diagnose insomnia.10 The disorder is associated with significant consequences and comorbidities, including psychological, physical, and occupational health impairment, and significant economic burden.5

Insomnia is highly comorbid with a number of psychological disorders and medical conditions,11–13 with up to 90% of insomnia disorders considered comorbid insomnia.12 The simultaneous presentation of insomnia and another condition was historically termed “secondary insomnia,” indicating that insomnia may be caused by, or a symptom of, another disorder, either of which may have promoted “undertreatment” of insomnia.5,14 Because limited understanding of the mechanistic pathways in insomnia makes it difficult to determine the direction of causality between insomnia and comorbid conditions,14 the term has been replaced with “comorbid insomnia” in DSM-5.1 This change highlights the recognition of insomnia as a contributor to other psychiatric and medical disorders, rather than simply a symptom of these conditions, as well as the importance of attending to both insomnia and the comorbid condition during treatment.5,12

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Comorbid insomnia and depression may have a different clinical course than either condition alone, and may require specific treatment procedures. Some work has shown that pathological sleep related cognitions may contribute to a more challenging clinical course of insomnia and may differentiate insomnia subgroups, but additional work is needed to clarify this issue.

Study Impact: The findings suggest that individuals with comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression reported more insomnia symptom-focused rumination than those with symptoms of insomnia without significant depression symptoms, even when controlling for insomnia and mental health severity. The findings highlight the need for increased clinical attention to the insomnia symptom-focused rumination reported by those with comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression.

Approximately 20% of patients in whom insomnia has been diagnosed exhibit some symptoms of depression,15 and nearly 41% of depressed patients meet diagnostic criteria for insomnia16; accordingly, Ohayon17 found depression to be the most common condition comorbid with insomnia. These findings point to the possibility that these disorders may be causally related to each other or may share common mechanisms.15 Moreover, several articles have reported that insomnia symptoms at baseline are associated with an increased risk of subsequent depression symptoms in the years following baseline assessment.18–20 The majority of follow-up assessments occurred an average of 1–6 y after baseline assessment, with one report noting that polysomnographic markers of insomnia were predictive of depression in addition to self-report indices.18 Thus, insomnia is an important indicator of the development of depression.

Because comorbidity is considered an aggravating factor to an index disease, some have suggested that comorbid insomnia and depression may have a different clinical course than either condition alone, and may thus require specific treatment procedures.15 Past work has shown that the risk of having a psychiatric diagnosis increases with insomnia severity,21 raising the possibility that insomnia comorbid with depression may have a more challenging clinical course or more severe associated symptoms simply because insomnia symptoms are more severe in this patient group than in those insomnia patients without significant depressive symptoms. Although a recent trial showed that group cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI) worked equally well at reducing insomnia among those treatment completers with high and low depression severity, insomnia severity remained higher among those with greater depression severity throughout treatment.22 Thus, questions remain as to how to enhance interventions to more effectively reduce insomnia severity in patients with depression.

The cognitive model of insomnia23 proposes that individuals with insomnia are susceptible to “excessive negatively toned cognitive activity” such as dysfunctional sleep related beliefs, worry, and rumination. Previous work in this area has largely focused on dysfunctional sleep related beliefs (i.e., unhelpful thought patterns focused on consequences of insomnia, worry/helplessness about insomnia, sleep expectations, and medication) and worry (i.e., concerns about future consequences and associated with anxiety). Specifically within the context of insomnia co-morbid with depression, Manber and colleagues22 noted differences in a cognitive treatment component relevant to sleep between those with high and low depression severity, specifically that those with greater depression severity had lower adherence to changing expectations about sleep. Thus, treatment-related changes in sleep-focused cognitions may be moderated by depression severity. Similarly, past work has shown that those with comorbid insomnia have dysfunctional beliefs about sleep that are similar to those with insomnia without significant depression after controlling for depressive symptoms.24 This suggests that dysfunctional beliefs about sleep are at least partially mediated by the distress associated with increased symptoms of depression among the comorbid group. Last, recent findings were unable to detect significant differences related to dysfunctional beliefs about sleep when comparing individuals with psychophysiologic insomnia and individuals with insomnia associated with a mental disorder.25 Only depressive symptomatology successfully discriminated the two groups using an analysis aimed at identifying which variable(s) best differentiated between the groups.

A less studied area within insomnia has been rumination (i.e., repeated focus on the causes or the “why” of the current problem), which may be particularly important in considering those with insomnia and depression given the association of rumination with dysphoria.26 Carney and colleagues' more recent work has focused on understanding insomnia symptom-focused rumination (i.e., repeated focus on what caused insomnia daytime symptoms such as fatigue).27–28 Unlike the results for dysfunctional sleep related beliefs, findings demonstrated an independent contribution of sleep related rumination in individuals with insomnia when also considering worry and depressive symptom severity27 as well as in individuals with insomnia and depression when also considering dysfunctional sleep related cognitions and depressive symptoms severity.28

Thus, it is likely that various areas of cognitive activity may be present for those with insomnia and depression, some of which (e.g., greater dysfunctional sleep related cognitions) may be accounted for primarily by elevated levels of distress and mood disturbance, rather than a characteristic of insomnia. However, it remains unclear whether measures specifically related to worry and insomnia symptom-focused rumination contribute to a more challenging clinical course and may differentiate insomnia subgroups. Understanding the complex nature of comorbid insomnia and depression symptoms is critical to identifying intervention targets that may reduce the severity and duration of insomnia and lessen the subsequent risk of developing symptoms of depression.

In this report we examined the clinical characteristics of individuals referred to an academic sleep center with comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression and those with symptoms of insomnia without significant depression, and we identified differences between these groups with regard to several cognitive-related variables. We hypothesized that level of state-dependent worry, level of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, and level of insomnia symptom-focused rumination would differ between individuals with comorbid symptoms and those with insomnia symptoms without significant depression, with the expectation that those with comorbid symptoms would report more severe pathology on our variables of interest. We also examined whether these differences would hold when accounting for level of mental health symptoms. Given that the majority of participants in the sample were referred to the sleep center for symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), we conducted a follow-up analysis controlling for the presence of OSA among those screened for OSA with a sleep study. This was done to control for the fact that the severity of cognitive-related variables may be an artifact of OSA symptoms.

METHODS

Procedure

The study consisted of a retrospective medical chart review examining all patients seen at the Wisconsin Sleep Clinic and Laboratory from December 2008 to May 2009. All data were extracted from paper and electronic medical charts with a waiver of informed consent and authorization. When initially referred, patients completed a comprehensive sleep assessment as part of the triage process. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Participants

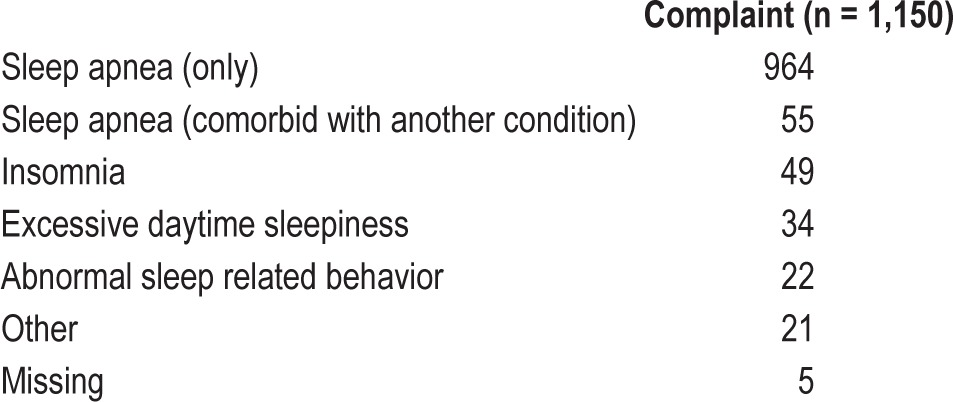

The initial sample included 1,150 consecutive patients aged 18 y or older who were referred to the sleep clinic or laboratory for a variety of sleep complaints and completed at least some of the comprehensive sleep assessment, which included questionnaires assessing demographic variables, insomnia severity, depressive symptoms, worry, insomnia symptom-focused rumination, and dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, among other questionnaires not used in the current study assessing OSA, parasomnias, narcolepsy, restless legs syndrome, daytime sleepiness, daytime fatigue, health-related quality of life, and medical and family history. Of this initial sample, 964 (83.8%) were referred primarily for OSA, with another 55 (4.8%) referred for OSA comorbid with another complaint (e.g., insomnia, restless leg syndrome). Table 1 shows the primary reasons for referral to the sleep clinic for all patients, which were gathered via retrospective chart review based on statement of reason for referral listed by the clinician. Most individuals were seen in the sleep clinic for evaluation (n = 757), where we gathered referral information. Those who did not have a clinic visit were seen in the sleep laboratory, typically for a sleep study. Referral reasons for those seen in the laboratory only were gathered from this visit. Participants were not excluded from the current analyses based on referral reason or based on results of a sleep study.

Table 1.

Reasons for referral to sleep clinic.

For the final study sample, participants were identified as having significant insomnia symptoms based on an Insomnia Severity Index (ISI29,30) score greater than or equal to 11, and those with an ISI less than 11 were excluded,30 leaving a final sample of 716. Those participants with significant insomnia symptoms who also had a Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS31,32) score above 10 were classified as having comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression, whereas those with QIDS scores at 10 or below were classified as having symptoms of insomnia without significant depression. Because of the potential overlap in symptoms between the ISI and QIDS, we identified those participants who had QIDS scores above 10 when sleep related items were excluded, and these participants comprised the group of individuals with insomnia symptoms in the context of meaningful symptoms of depression.

Measures

The ISI is a self-report measure that assesses insomnia severity over the course of the previous 2 w. It includes seven items, which measure insomnia symptom severity on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). The ISI score is obtained by adding individual item scores, with higher scores indicating greater insomnia severity. This measure has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity in the general population. Although early work suggested a score of 15 or above as indicating clinically significant insomnia,29 more recent work has shown that a score of 11 was optimal for detecting insomnia among a clinical sample, with 97.2% sensitivity and perfect 100% specificity.30 Still, because the original ISI measure identified scores of 15 and above as indicative of clinical insomnia, all analyses were repeated using ISI of 15 as the cutoff. The results did not differ meaningfully when using ISI of 15 compared to a score of 11, so the cutoffs using ISI of 11 are reported here.

The QIDS assesses depressive symptoms. It is a 16-item scale, with each item rated on a four-point scale. Total scores range from 0 to 27 with higher scores reflecting greater symptom severity. Previous work has established scores in the range of 6 to 10 to indicate mild depressive symptoms.31,33 The QIDS includes several items that measure sleep disturbance. As previously noted, we computed a second version of the QIDS that excluded sleep related items (QIDS_nosleep), in order to reduce the redundancy of the QIDS and ISI. This version of the QIDS, with a range of 0 to 23, was used in all analyses. However, we repeated the analyses when including participants whose QIDS score was above 10 when including all items, without meaningful differences in the results. Thus, the results using the more stringent classifications are reported here.

The Penn State Worry Questionnaire-Past Week (PSWQ-PW34) is a 15-item scale that was adapted from the original PSWQ.35 It assesses state-dependent worry focused specifically on future consequences. Individuals rate each item on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all typical) to 5 (very typical). Some items are reversed scored, and then all items are summed into a single score ranging from 15 to 75, with higher scores indicating more worry. Previous work has suggested that a cutoff of 45 differentiates individuals with generalized anxiety disorder from healthy controls on the PSWQ.36 The PSWQ-PW has been used previously to measure worry in a clinical insomnia population.27

The Daytime Insomnia Symptom Response Scale (DISRS27,37) was designed to assess ruminative tendencies in insomnia populations, particularly repetitive thought about the causes of daytime symptoms of insomnia. The scale was adapted from the eight-item Symptom-Focused Rumination Subscale (SYM38) of the Response Styles Questionnaire (RSQ39). Twelve additional items were added, resulting in a 20-item scale in which individuals are asked how frequently they engage in specific behaviors listed when feeling tired. Items, which are scored on a four- point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always), are summed to obtain the total score. Higher scores indicate higher levels of rumination. This scale showed highly acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach alpha of 0.93 and 0.94) when tested in two samples. Previous work has shown that a clinical sample of individuals with depression and insomnia report a mean of 56.2 (standard deviation [SD] = 11.6) on this measure, while a group of undergraduates reported an average score of 41.43 (SD = 11.42) on the DISRS.37

The Dysfunctional Beliefs About Sleep Scale (DBAS-1640) is a 16-item scale that measures sleep-disruptive cognitions. This measure, which is a shortened version of the original 30-item questionnaire,41 has four factors that reflect perceived consequences of insomnia, worry/helplessness about insomnia, sleep expectations, and medication. For each statement, the person rates his or her level of agreement/disagreement on a zero to 10-point Likert scale anchored at one end by “strongly disagree” and at the other end by “strongly agree.” The total score is based on the average of all items, with higher scores indicating more dysfunctional beliefs about sleep. Previous work has suggested that a cutoff of 3.8 be used to differentiate individuals presenting at a community sleep clinic from healthy controls.42

The Mental Health Scale of the Short Form (SF)-3643–46 contains five items of the larger 36-item scale, which assess psychological distress and well-being. Lower scores indicate increased feelings of depression and nervousness. This scale shows highly acceptable levels of reliability, based on measures of internal consistency (Cronbach alpha 0.84) and alternate forms (Cronbach alpha 0.93).43,46 Moreover, the mental health scale has demonstrated validity in discriminating patients with psychiatric conditions from those with other medical conditions and discriminating severity levels among those with a psychiatric condition.44;45

Statistical Analyses

SPSS Statistics version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NJ) was used for all study analyses. We first examined descriptive statistics of those individuals who were included in our analyses. We compared the demographic and clinical variables of included individuals who had comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression with those who had insomnia symptoms without significant depression, in order to identify meaningful differences between the groups. To test our hypothesis that insomnia symptoms in the context of meaningful depression differed from insomnia symptoms without significant depression, we conducted logistic regression analyses examining whether the cognitive-related variables of interest predicted participant group membership. We added demographic and clinical variables relevant to group membership to later steps of the models as covariates.

RESULTS

Descriptive Analyses

Of the 1,150 consecutive patients in the initial sample, 716 completed the QIDS (when sleep items were excluded) and ISI, had an ISI score of 11 or higher, and were included in the main analyses of this study. Demographic and clinical variables of the total included sample are shown in Table 2. The majority of the included sample was male (53.5%) and married (58.2%), with a mean age of 47.55 years (SD = 13.70) and average body mass index (BMI) in the “obese” category.

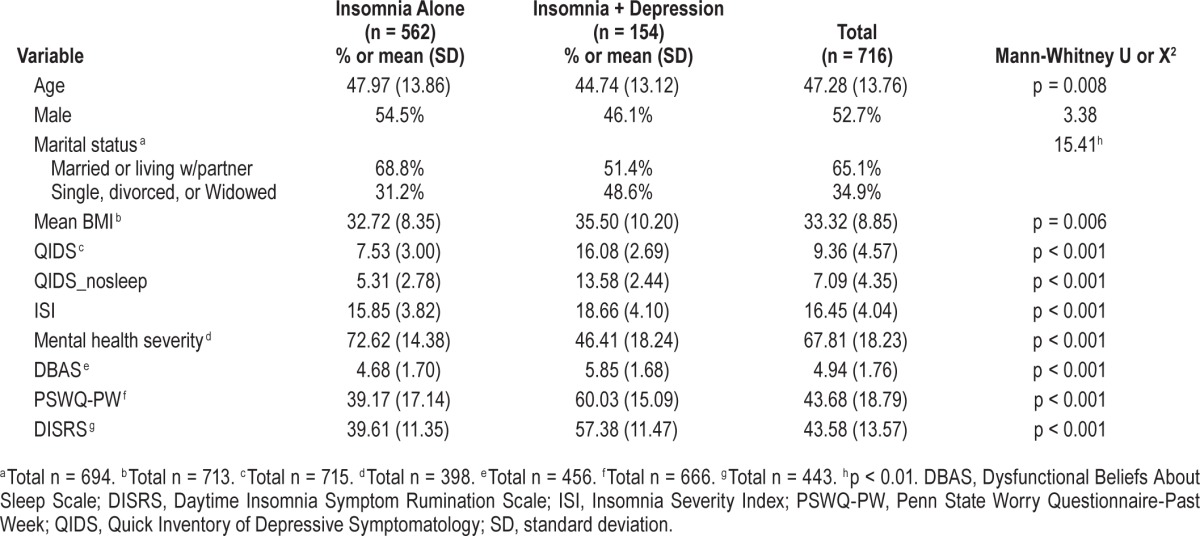

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals with insomnia alone and insomnia comorbid to depression.

Table 2 also shows the means and standard deviations of the demographic and clinical variables of included participants who had insomnia symptoms either with or without significant symptoms of depression. As can be seen in Table 2, participants in the two groups differed significantly on all variables of interest, with the exception of the proportion of males/females in each group. Those with insomnia comorbid with depression were significantly younger, significantly more likely to be single (versus married), and had significantly higher scores on the QIDS, ISI, Mental Health Severity Scale, DBAS-16, PSWQ-PW, and DISRS than those with insomnia without significant depression.

Hypothesis-Testing Analyses

In univariate logistic regression analyses, several clinical variables significantly predicted whether participants had comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression or insomnia symptoms without meaningful depression. Specifically, the two groups were distinguished by scores on the DBAS-16 (Exp(β) = 1.50, p < 0.000, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.30–1.73), DISRS (Exp(β) = 1.14, p < 0.000, CI = 1.11–1.18), and PSWQ-PW (Exp(β) = 1.08, p < 0.000, CI = 1.06–1.09). The Mann-Whitney U test showed that individuals who have comorbid symptoms report higher insomnia severity than those who have insomnia symptoms only (p < 0.0001). Thus, ISI score, as well as other relevant demographic and clinical variables of interest were added to the models, including age, sex, marital status, and BMI. The predictive value of the DBAS-16 (Exp(β) = 1.30, p = 0.002, CI = 1.10–1.54), DISRS (Exp(β) = 1.14, p < 0.000, CI = 1.10–1.17), and PSWQ-PW (Exp(β) = 1.07 p < 0.000, CI = 1.06–1.09) remained significant even when relevant covariates were added.

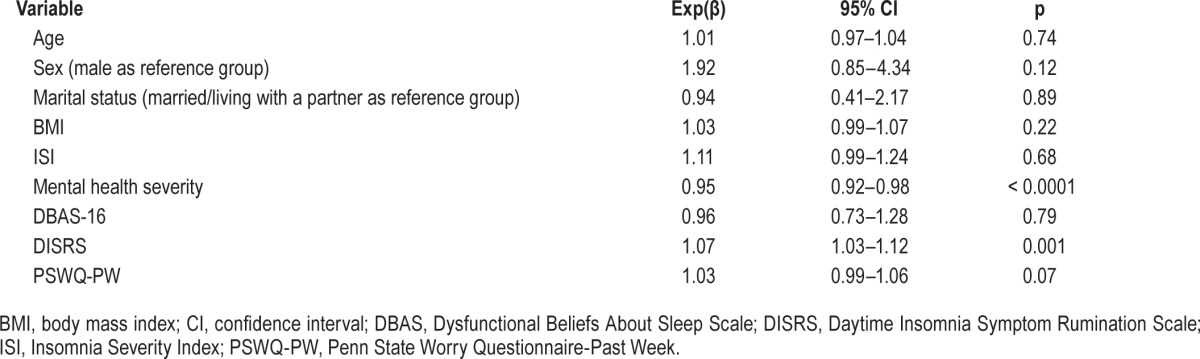

Because we wanted to rule out the possibility that the predictive ability of the DBAS-16, DSIRS, and PSWQ-PW may be an artifact of increased levels of depression among one group relative to the other, we repeated our analyses controlling for the mental health severity scale of the SF-36. The results showed that in all models, DISRS remained a significant predictor of group status, even when controlling for insomnia severity and mental health severity, among other relevant covariates (Exp(β) = 1.08, p < 0.0001, CI = 1.04–1.13), indicating the ability of insomnia symptom-focused rumination to differentiate individuals with comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression from those with insomnia symptoms without meaningful depression. In order to determine which measures discriminate our two groups, we repeated our original logistic regression analyses including all three measures as predictors of group, controlling for insomnia and mental health severity as well as other relevant covariates. We found that only DISRS remained a significant predictor of group status (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression predicting insomnia alone versus insomnia + depression group membership with DBAS-16, DISRS, PSWQ-PW.

Because most individuals in this sample presented to the sleep clinic with a complaint of sleep apnea, we re-ran our original analyses including sleep apnea screen outcome as a covariate (apnea-hypopnea index [AHI] > 5 = 1; AHI ≤ 5 = 0). This analysis included only those patients who underwent polysomnography to detect sleep apnea (n = 610 total; n = 393 AHI > 5; n = 217 AHI ≤ 5). The results remained unchanged. Specifically, when all three measures were entered as predictors of group, and when controlling for insomnia and mental health severity as well as other relevant covariates, DSIRS significantly differentiated the groups (Exp(β) = 1.08, p = 0.002, CI = 1.03–1.13).

DISCUSSION

The current study evaluated the clinical characteristics of individuals referred to an academic sleep center with comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression and those with symptoms of insomnia without significant depression, and identified differences between these groups with regard to cognitive-related variables. We found that individuals with comorbid symptoms reported more dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, past week worry, and insomnia symptom-focused rumination, than those with insomnia symptoms without significant depression. Insomnia symptom-focused rumination continued to differentiate the groups even when controlling for insomnia severity, mental health severity, and the presence of OSA. This indicates that the association of comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression with more severe symptoms and relevant dimensions is not due exclusively to greater insomnia severity, mental health severity, or to the presence of OSA. Rather, there may be something qualitatively different about the insomnia experienced by these two patient groups.

When including all three cognitive-related variables in our model, those with comorbid symptoms reported more severe insomnia symptom-focused rumination, even when insomnia and mental health severity were accounted for. This finding supports past work indicating that rumination and worry are discrete constructs,27 that rumination differentiates good and poor sleepers,26 and that it contributes to sleep quality47; but, it is also consistent with Manber and colleagues'22 suggestion that the efficacy of CBTI may be enhanced among individuals with comorbid insomnia and depression by paying greater attention to cognitive factors. Specifically, intervention for insomnia symptoms in the context of meaningful depression may be improved by targeting rumination related to daytime symptoms of insomnia. Thus, clinicians may elect to devote additional treatment time to cognitive strategies such as: (1) utilizing thought records to record symptom-focused ruminations; (2) challenging relevant cognitions via behavioral experiments; and (3) using acceptance-based approaches that target metacognitive processes in order to regulate emotional distress associated with insomnia (see reference 48 for a review of acceptance-based strategies for disturbed sleep).

These findings provide additional empirical support for the idea that poor sleepers experience rumination and dysfunctional beliefs about sleep26,27,49 and that those with comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression report higher levels of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep than those with insomnia without comorbidities.24,42 Although we might have expected individuals with comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression to report higher levels of depression-related rumination, our findings contribute novel support for the idea that insomnia symptom-focused rumination is more severe in the comorbid sample relative to those with insomnia symptoms without significant depression. Moreover, to our knowledge, this is the first examination of clinical differences between insomnia subgroups that utilized an entirely clinic-referred sample. Our clinic sample was largely referred for evaluation of OSA and many within the sample received a diagnosis of OSA, which may have contributed to the worry, dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, and insomnia symptom-focused rumination reported by these patients based on additional noninsomnia sleep related concerns. These may include gasping or apneic episodes, snoring, and headaches. Nevertheless, our primary findings remained significant even when accounting for the presence of laboratory-determined OSA. Moreover, although only 49 participants were primarily referred for insomnia, 716 of the entire group reported an ISI score of 11 or greater. This highlights the need for increased awareness of the high prevalence of meaningful insomnia symptoms in those suspected of OSA and with an OSA diagnosis and a consideration of treatment recommendations that considers more complex patients who may present with a number of comorbidities, including OSA, insomnia, and depression.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several strengths and limitations. First, our study utilizes the DISRS, a self-report measure expressly designed to evaluate rumination specifically related to insomnia. Because symptoms of insomnia and depression often overlap, which may mask the true influence of insomnia symptom-focused rumination, this measure has the advantage of parsing out rumination related to consequences of insomnia from rumination related to depression. Though introduced relatively recently, this measure has shown highly acceptable internal consistency in a group of patients with comorbid depression and insomnia. Moreover, the ability of insomnia symptom-focused rumination to differentiate our patient groups, even when operationalizing depression symptoms in multiple ways and when including covariates related to sleep disordered breathing, speaks to the robust nature of our results. The use of data from a large, representative sample of patients presenting to a sleep clinic is also a strength because it increases the generalizability of our results to a general population of patients referred to a sleep clinic who are likely to have various comorbidities and presenting complaints, including OSA. One limitation is that the data used in these analyses were gathered via retrospective chart review, rather than as part of a particular protocol. Thus, not every patient had the same evaluation, and the referral reason was gathered from a sleep laboratory visit note, rather than a clinic visit note, for 393 of the 1,150 patients included in the full chart review. However, all subjects, whether seen in the sleep laboratory or sleep clinic, completed the same comprehensive sleep questionnaire. Additionally, we are unaware of validity data in support of the QIDS in those with comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression, which may constitute another limitation. Last, this study examines the characteristics of our patient groups cross-sectionally. Future work should examine comorbid insomnia and depression longitudinally, which may illustrate the time course of insomnia and depression symptoms, providing clues as to the complex, and perhaps causative, interactions between these two forms of pathology.

Overall, we conclude that individuals with comorbid symptoms of insomnia and depression reported higher insomnia symptom-focused rumination than those with insomnia symptoms outside of significant depression among a sample primarily referred for sleep apnea evaluation. Insomnia symptom-focused rumination remained significantly different between the groups even when accounting for insomnia severity, mental health severity, and OSA. The findings contribute to our understanding of the complex nature of comorbid insomnia and depression symptoms and the specific symptom burden experienced by those with significant depression in the presence of insomnia. The findings also highlight the need for increased clinical attention to insomnia symptom-focused rumination reported by these patients, as well as the need for additional work that tests whether a greater treatment focus on these areas is associated with greater insomnia treatment efficacy and a longer duration of remission.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This study was supported by the Center for Sleep Medicine and Research, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI and Grant HL082610. Drs. Rumble and Benca have received research support from Merck. Dr. Benca also is a consultant to Merck and Jazz. Dr. Levenson has received royalties from American Psychological Association Books and grant support from the American Psychological Foundation. She is supported by HL082610. This work was performed at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was performed at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. It was supported by the Center for Sleep Medicine and Research, University of Wisconsin, Madison and Grant HL082610 from the National Institutes of Health. The authors with to thank Daniel J. Buysse, MD for his feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- BMI

body mass index

- CBTI

cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia

- CI

confidence interval

- DBAS

Dysfunctional Beliefs About Sleep Scale

- DISRS

Daytime Insomnia Symptom Response Scale

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- ISI

Insomnia Severity Index

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PSWQ-PW

Penn State Worry Questionnaire-Past Week

- QIDS

Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology

- RSQ

Response Styles Questionnaire

- SD

standard deviation

- SYM

Symptom-Focused Rumination Subscale

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. The international classification of sleep disorders, 2nd ed.: Diagnostic and coding manual. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh JK, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, et al. Nighttime insomnia symptoms and perceived health in the America Insomnia Survey (AIS) Sleep. 2011;34:997–1011. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morin CM, Jarrin DC. Insomnia and healthcare-seeking behaviors: impact of case definitions, comorbidity, sociodemographic, and cultural factors. Sleep Med. 2013;14:808–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohayon MM, Reynolds CF. Epidemiological and clinical relevance of insomnia diagnosis algorithms according to the DSM-IV and the Iinternational Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) Sleep Med. 2009;10:952–60. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Belanger L, et al. Prevalence of insomnia and its treatment in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56:540–8. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morin CM, Benca R. Chronic insomnia. Lancet. 2012;379:1129–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60750-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth T, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, et al. Prevalence and perceived health associated with insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR; International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; and Research Diagnostic Criteria/International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition criteria: results from the America Insomnia Survey. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth T, Jaeger S, Jin R, et al. Sleep problems, comorbid mental disorders, and role functioning in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:1364–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichstein KL, Taylor DJ, McCrae CS, et al. Insomnia: epidemiology and risk factors. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practices of sleep medicine. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 827–37. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dikeos D, Georgantopoulos G. Medical comorbidity of sleep disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:346–54. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283473375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NIH State of the Science Conference Statement Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults. Sleep. 2005;28:1049–57. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Staner L. Comorbidity of insomnia and depression. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart R, Besset A, Bebbington P, et al. Insomnia comorbidity and impact and hypnotic use by age group in a national survey population aged 16 to 74 years. Sleep. 2006;29:1391–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohayon MM. Prevalence of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of insomnia: distinguishing insomnia related to mental disorders from sleep disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31:333–46. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szklo-Coxe M, Young T, Peppard PE, et al. Prospective associations of insomnia markers and symptoms with depression. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:709–20. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riemann D, Voderholzer U. Primary insomnia: a risk factor to develop depression? J Affect Disord. 2003;76:255–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarsour K, Morin CM, Foley K, et al. Association of insomnia severity and comorbid medical and psychiatric disorders in a health plan-based sample: insomnia severity and comorbidities. Sleep Med. 2010;11:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manber R, Bernert RA, Suh S, et al. CBT for insomnia in patients with high and low depressive symptom severity: adherence and clinical outcomes. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:645–52. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harvey AG. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:869–93. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carney CE, Edinger JD, Manber R, et al. Beliefs about sleep in disorders characterized by sleep and mood disturbance. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62:179–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohn L, Espie CA. Sensitivity and specificity of measures of the insomnia experience: a comparative study of psychophysiologic insomnia, insomnia associated with mental disorder and good sleepers. Sleep. 2005;28:104–12. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carney CE, Edinger JD, Meyer B, et al. Symptom-focused rumination and sleep disturbance. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4:228–41. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0404_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carney CE, Harris AL, Moss TG, et al. Distinguishing rumination from worry in clinical insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:540–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carney CE, Moss TG, Lachowski AM, et al. Understanding mental and physical fatigue complaints in those with depression and insomnia. Behav Sleep Med. 2014;12:272–89. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2013.801345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, et al. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:573–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med. 2004;34:73–82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rush AJ, Bernstein IH, Trivedi MH, et al. An evaluation of the quick inventory of depressive symptomatology and the hamilton rating scale for depression: a sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression trial report. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stober J, Bittencourt J. Weekly assessment of worry: an adaptation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for monitoring changes during treatment. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:645–56. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, et al. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28:487–95. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Behar E, Alcaine O, Zuellig AR, et al. Screening for generalized anxiety disorder using the Penn State Worry Questionnaire: a receiver operating characteristic analysis. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2003;34:25–43. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(03)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carney CE, Harris AL, Falco A, et al. The relation between insomnia symptoms, mood, and rumination about insomnia symptoms. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:567–75. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bagby RM, Rector NA, Bacchichi JR, et al. The stability of the Response Styles Questionnaire scale in a sample of patients with major depression. Cognitive Ther Res. 2004;28:527–38. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991:61115–21. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morin CM, Vallieres A, Ivers H. Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (DBAS): validation of a brief version (DBAS-16) Sleep. 2007;30:1547–54. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morin CM. New York-London: The Guilford Press; 1993. Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carney CE, Edinger JD, Morin CM, et al. Examining maladaptive beliefs about sleep across insomnia patient groups. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McHorney CA, Ware JE., Jr Construction and validation of an alternate form general mental health scale for the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey. Med Care. 1995;33:15–28. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS-36-Item short form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–63. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric, Incorporated; 2000. How to score version two of the SF-36 Health Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zoccola PM, Dickerson SS, Lam S. Rumination predicts longer sleep onset latency after an acute psychosocial stressor. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:771–5. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181ae58e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ong JC, Ulmer CS, Manber R. Improving sleep with mindfulness and acceptance: a metacognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50:651–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carney CE, Edinger JD. Identifying critical beliefs about sleep in primary insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:342–50. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]