Abstract

Background:

Migraine is the most common chronic neurological disorders that may be associated with vasodilatation. According to the role of prostaglandin I2 (prostacyclin) receptor (PTGIR) in migraine as a receptor, which acts in vasodilatation, we decided to study the changes of PTGIR expression in migraine patients in relation to a suitable control group.

Materials and Methods:

Extracted mRNA from lymphocytes of 50 cases and 50 controls was used to synthesize cDNA. Real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed, and the data were analyzed. Our results show that PTGIR mRNA expression in cases was significantly higher than the control group (P = 0.010).

Results:

In conclusion, mRNA expression of PTGIR in the blood of people with migraines could be considered as a biomarker.

Conclusion:

In addition, repression of PTGIR gene expression by methods such as using siRNA is probably suitable for therapy of migraine patients.

Keywords: Biomarker, expression, migraine, prostaglandin I2, receptor

INTRODUCTION

Migraine is the most common chronic neurological disorders, which affects over 15% of populations. Patients show moderate to severe headaches often associated with autonomic nervous system. Some other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and generally the pain is worse with physical activity.[1,2] Migraines are believed to be related to a mixture of environmental and genetic factors. However, the underlying causes of migraines are not identified.[3]

The Pathophysiology of migraine show that is a neurovascular disorder.[4] Furthermore, some evidences showing its mechanism begins within the brain and then spreading to the blood vessels and, therefore, neuronal mechanisms play a greater role while other researchers believe that blood vessels play the main role. Others believe that probably both are important.[5,6,7]

Prostaglandin I2 (prostacyclin) (PGI2) is an eicosanoid molecule of the cyclooxygenase pathway, which inhibits the formation of the platelet plug involved in primary hemostasis as a part of the blood clot formation. It is also an important and effective vasodilator.[8,9] PGI2 binds to platelet Gs protein-coupled receptor (prostacyclin receptor) and activates it. This activation leads to the production of cAMP, which goes on to activate protein kinase A (PKA). Followed by a cascade of activity; PKA dephosphorylates the myosin light chain and inhibits myosin light-chain kinase. This will eventually lead to vasodilatation.[10,11,12]

Therefore, since these receptors are as a part of vasodilator factors during the disease attacks, probably play an important role in the mechanism of this disease. In migraine, a common disorder in these receptors exists and since prostaglandin I2 (prostacyclin) receptor (PTGIR) is also present on the lymphocyte membrane, it is expected that these changes are also seen in lymphocytes. In studies that have been done so far about the receptor of PGI2 in migraine, the effect of inhibitors has been noticed.[13,14]

According to what was mentioned and because of the role of PTGIR in migraine, we decided to study the changes of expression in migraine patients in relation to a suitable controls group to find any significance changes in expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and samples

Our sample consisted of 50 patients affected with migraine from the local hospitals in Isfahan province (Khorshid Hospital). All the patients were diagnosed as migraine, using the classification of all headaches, including migraines, is organized by the International Headache Society, and published in the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD). The current version, the ICHD-2, was published in 2004.[1] Following the referral of patients to a neurologist and final diagnosis of patients with clinical and para-clinical examinations, the ethical consent was obtained from patients. The migraine patients did not take an antipsychotic medicine when we took blood samples and the minimum washout was 3 weeks.

The controls group included 50 unrelated individuals without any neurological disorders. They were matched for age and gender with the patient group. General physical and neurological examinations, neuropsychological evaluations were conducted to confirm the accuracy of the clinical diagnosis. Some general data such as date of birth, the date of diagnosis, occupation, and geographical region were also obtained. Peripheral blood was obtained from the patients and controls group.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Lymphocyte cells were isolated from ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid–blood using density-gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque, Sigma, Germany, 100 ml, CN: 17-440-02) and then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (Gibco-BRL, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Denmark, 100 ml, CN: 14190-086). TRIZOL (TRIzol® RNA Isolation Reagents, Invitrogen, Life Technologies Corporation, USA, 100 ml, CN: 15596-026) was used for RNA extraction from the isolated lymphocyte cells according to the standard protocols of the manufacturer. For each sample, RNA concentration was determined by spectrophotometer and stored at −80°C. Generally, 260/280 ratio for samples was >1.8. Then, cDNA synthesis kit (RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, Thermo Scientific, CN. K1622) was used to synthesize cDNA by oligo dT primer (RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Denmark, CN. K1622) from the extracted RNA of samples according to standard protocol of the manufacturer.

Primers and real-time polymerase chain reaction procedure

Primers were designed using Allele ID version 7.6. Primers were synthesized by and purchased from Bioneer (in South Korea). According to the cDNA sequence (Gene bank), the sequences of the primers used for real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of PTGIR mRNA were as follows: Forward primer, 5’‑ CCT GCC TCT CAC GAT CCG‑3’ and reverse primer, 5’‑ AAG GCG TAG AAG CGG AAG‑3’. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) selected as house-keeping gene in our assays. The primers sequences were as follows: Forward primer, 5’‑ AAG CTC ATT TCC TGG TAT G‑3’; and reverse primer, 5’‑ CTT CCT CTT GTG CTC TTG‑3’.

Real-time-PCR was performed with a StepOnePlus TM RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA). Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 10 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 60 s at 60°C. The specificity of the amplification reaction was determined by a melting curve analysis acquired by measuring fluorescence of SYBR Green I during a linear temperature transition from 65°C to 95°C at 0.3°C/s. Relative quantification was performed through normalizing various gene signals using GAPDH signal as a reference gene. PCR reactions were accomplished in triplicate in a 20 μl volume, including 400 ng cDNA, 10 μl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix [2X] [Thermo Scientific, CN. K0222]), nuclease-free water and 0.25 μmol forward and reverse primers.

Statistical analysis

LinReg PCR version 7.5 (software for analysis of RT-PCR data) was used and also Relative Expression Software Tool – XL = REST-XL©-version 3, Hentze Group, Germany (calculation software for the relative expression in RT-PCR using Pair Wise Fixed Reallocation Randomization Test©, Hentze Group, Germany) and Relative Expression Software Tool 2009 (REST version 2.0.7, IBM company, USA, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) were used for the calculation of relative expression. The amounts of PTGIR mRNA in the lymphocyte standardized to the GAPDH mRNA by ΔΔCt method. All the other statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS for windows software (version 16, produced by SPSS Inc., IBM company, USA). The independent two-tailed t-test was used for comparison of mRNA expression.

RESULTS

Clinical variables

A case–control study consisted of 50 patients affected by migraine and 50 normal controls. The 50 patients had a mean age of 35.235 ± 10.99 years (range, 9–60 years) and female: male ratio in this group was 4:1. The 50 controls had a mean age of 35.058 ± 11.116 years (range, 8–59 years) and female: male ratio in this group was 3.7:1.3.

mRNA expression of prostaglandin I2 (prostacyclin) receptor

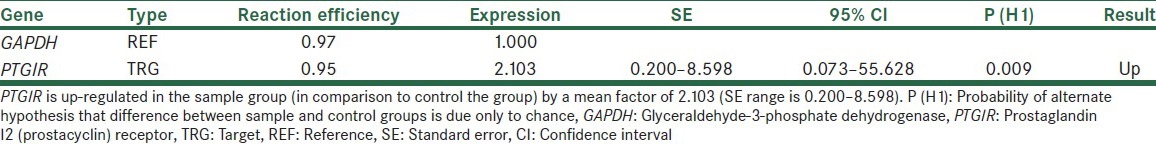

When we calculated relative expression, it showed up-regulation for cases than controls samples. PTGIR in the sample group (in comparison to controls group) is up-regulated by a mean of 2.103 (standard error range is 0.200–8.598) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Normalized relative expression of PTGIR gene

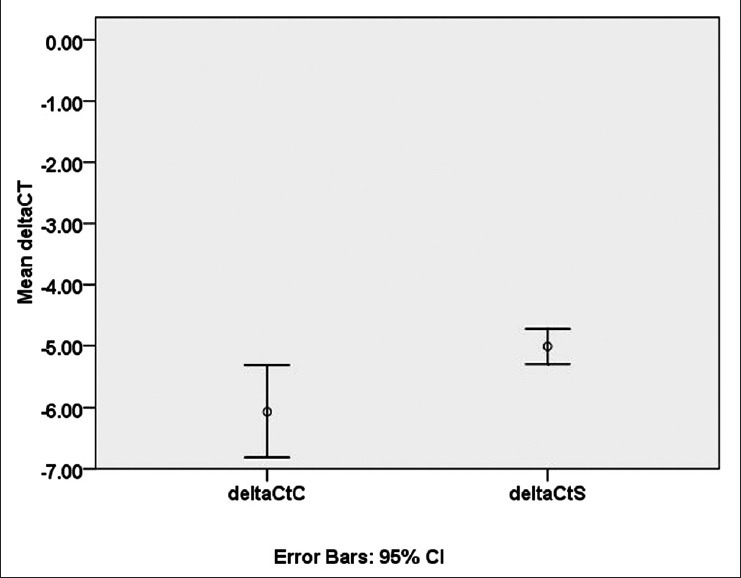

Comparison of −ΔCt of PTGIR mRNA expression between migraine patients and the controls group showed that controls group had lower −ΔCt than the patient group [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Comparison of −ΔCt for prostaglandin I2 (prostacyclin) receptor (PTGIR) mRNA expression between cases and controls. Relative expression of PTGIR mRNA in migraine patients is significantly higher than the control group. CI; confidence interval, deltaCtC; delat Ct of Controls, deltaCtS; delat Ct of Samples

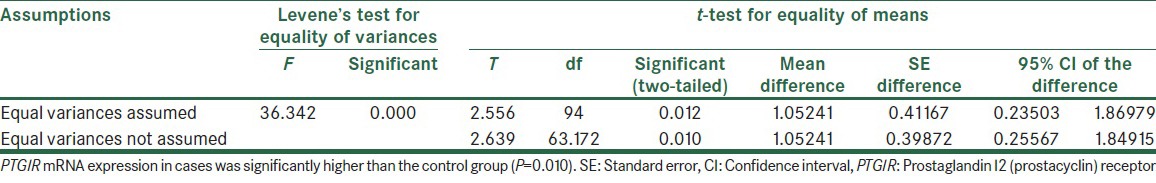

Furthermore, independent two-tailed t-test showed that PTGIR mRNA expression in cases was significantly higher than controls group (P = 0.010) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Independent samples test analysis on-ΔCt of cases and control samples

DISCUSSION

The pathophysiology of migraine is complex, and its mechanisms are not identified, but the role of vasodilatation, neurogenic inflammation, and the central neuronal theory are more important topics in migraine studies.[15]

Some genes associated with migraine are listed. However, the role of these loci in migraine may be unknown. Determining of genes involved in the pathophysiology of migraine has major problems. First, there is no objective diagnostic test to evaluate the cases. Second, migraine is a polygenic disease and is considered as a multifactorial disorder.[16]

The human prostacyclin receptor has been identified as one of the seven transmembrane G-proteins coupled receptor, which plays an important roles in atheroprevention and cardioprotection.[17] The critical cardio‑, vasculo‑, and cytoprotective roles of prostacyclin (PGI2) have been well researched in multiple animal models. Furthermore, PGI2 receptor participates in signal transduction of the pain response, cardioprotection, and inflammation.[18,19,20,21] However, its function in human disease has been less clear.

Studies in healthy individuals showed that PGI2 induced headache and dilatation of both extra- and intra-cerebral arteries. Delayed migraine-like attacks after PGI2 infusion have been reported in migraine patients and similar to normal volunteers immediate dilatation of extra-and intra-cerebral arteries was observed.[22,23] PGI2 infusion caused immediate headache in 92% of migraine patients and it is associated with a significant drop in the mean flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery (MCA) (−10.5%) and dilatation of the superficial temporal artery (32.9%).[24] Migraine-like attacks after PGI2 infusion have been reported in 75% of patients.[23,25]

Recently, prostaglandin I receptor mRNA transcripts were revealed in rat cranial arteries. Furthermore, IP receptor protein was aggregated to smooth muscle of the MCA, middle meningeal artery and basilar artery.[26]

Previous studies have focused mainly on increasing the amount of PGI2 in migraine, and PGI2 receptor has not been systematically studied in patients with migraine. In this study, we investigated the expression levels of PTGIR and significant difference of PTGIR expression in the blood of migraine patients compared with healthy controls shows that increased PTGIR may play a critical role in migraine and triggers migraine attacks in migraineurs. Accordingly, two conclusions can be found. First, mRNA expression of PTGIR in the blood of people with migraine could be considered as a biomarker. Second, using siRNA could be considered as a choice to inhibit of PTGIR expression for therapeutic aims. In addition, repression of PTGIR gene expression by methods such as using siRNA is probably suitable for therapy of migraine patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Conflict of Interest:The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia. (2nd edition) 2004;24(Suppl 1):9–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limmroth V, Michel MC. The prevention of migraine: A critical review with special emphasis on beta-adrenoceptor blockers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:237–43. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piane M, Lulli P, Farinelli I, Simeoni S, De Filippis S, Patacchioli FR, et al. Genetics of migraine and pharmacogenomics: Some considerations. J Headache Pain. 2007;8:334–9. doi: 10.1007/s10194-007-0427-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartleson JD, Cutrer FM. Migraine update. Diagnosis and treatment. Minn Med. 2010;93:36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goadsby PJ. The vascular theory of migraine – A great story wrecked by the facts. Brain. 2009;132:6–7. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan KC, Charles A. An update on the blood vessel in migraine. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:266–74. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833821c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodick DW. Examining the essence of migraine – Is it the blood vessel or the brain. A debate? Headache. 2008;48:661–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizzo MT. Cyclooxygenase-2 in oncogenesis. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:671–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka Y, Yamaki F, Koike K, Toro L. New insights into the intracellular mechanisms by which PGI2 analogues elicit vascular relaxation: Cyclic AMP-independent, Gs-protein mediated-activation of MaxiK channel. Curr Med Chem Cardiovasc Hematol Agents. 2004;2:257–65. doi: 10.2174/1568016043356273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boron WF, Boulpaep EL. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders; 2005. Medical Physiology: A Cellular and Molecular Approaoch. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haynes J, Jr, Robinson J, Saunders L, Taylor AE, Strada SJ. Role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in cAMP-mediated vasodilation. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H511–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.2.H511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Negash S, Gao Y, Zhou W, Liu J, Chinta S, Raj JU. Regulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated vasodilation by hypoxia-induced reactive species in ovine fetal pulmonary veins. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L1012–20. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00061.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilfeather SA, Massarella A, Gorgolewska G, Ansell E, Turner P. Beta-adrenoceptor and epoprostenol (prostacyclin) responsiveness of lymphocytes in migraine patients. Postgrad Med J. 1984;60:391–3. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.60.704.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puig-Parellada P, Planas JM, Giménez J, Sánchez J, Gaya J, Tolosa E, et al. Plasma and saliva levels of PGI2 and TXA2 in the headache-free period of classical migraine patients. The effects of nicardipine. Headache. 1991;31:156–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1991.hed3103156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho TW, Edvinsson L, Goadsby PJ. CGRP and its receptors provide new insights into migraine pathophysiology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:573–82. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ducros A, Tournier-Lasserve E, Bousser MG. The genetics of migraine. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:285–93. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stitham J, Arehart EJ, Gleim S, Douville K, MacKenzie T, Hwa J. Arginine (CGC) codon targeting in the human prostacyclin receptor gene (PTGIR) and G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) Gene. 2007;396:180–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao CY, Hara A, Yuhki K, Fujino T, Ma H, Okada Y, et al. Roles of prostaglandin I (2) and thromboxane A (2) in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury: A study using mice lacking their respective receptors. Circulation. 2001;104:2210–5. doi: 10.1161/hc4301.098058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng Y, Austin SC, Rocca B, Koller BH, Coffman TM, Grosser T, et al. Role of prostacyclin in the cardiovascular response to thromboxane A2. Science. 2002;296:539–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1068711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egan KM, Lawson JA, Fries S, Koller B, Rader DJ, Smyth EM, et al. COX-2-derived prostacyclin confers atheroprotection on female mice. Science. 2004;306:1954–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1103333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Southall MD, Vasko MR. Prostaglandin receptor subtypes, EP3C and EP4, mediate the prostaglandin E2-induced cAMP production and sensitization of sensory neurons. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16083–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wienecke T, Olesen J, Oturai PS, Ashina M. Prostacyclin (epoprostenol) induces headache in healthy subjects. Pain. 2008;139:106–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wienecke T, Olesen J, Ashina M. Prostaglandin I2 (epoprostenol) triggers migraine-like attacks in migraineurs. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:179–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antonova M, Wienecke T, Olesen J, Ashina M. Prostaglandins in migraine: Update. Curr Opin Neurol. 2013;26:269–75. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328360864b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonova M. Prostaglandins and prostaglandin receptor antagonism in migraine. Dan Med J. 2013;60:B4635. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-14-S1-P114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myren M, Olesen J, Gupta S. Pharmacological and expression profile of the prostaglandin I (2) receptor in the rat craniovascular system. Vascul Pharmacol. 2011;55:50–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]