Abstract

Background

Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum (S. Pullorum) causes Pullorum disease (PD), a severe systemic disease of poultry and results in considerable economic losses in developing countries. In order to develop a safe and immunogenic vaccine, the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of S06004ΔSPI2, a Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI2) deleted mutant of S. Pullorum was evaluated in 2-day old chickens.

Results

Single intramuscular vaccination with S06004ΔSPI2 (2 × 107 CFU) of chickens revealed no differences in body weight or clinical symptoms compared to control group. S06004ΔSPI2 bacteria can colonize and persistent in liver and spleen of vaccinated chickens approximately 14 days, and specific humoral and cellular immune responses were significantly induced. Vaccination of chickens offered efficient protection against S. Pullorum strain S06004 and S. Gallinarum strain SG9 challenge, respectively, at 10 days post vaccination (dpv) based on mortality and clinical symptoms compared to control group.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that S06004ΔSPI2 appears to be a highly immunogenic and efficient live attenuated vaccine candidate.

Keywords: Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum, Pullorum disease, Salmonella pathogenicity island 2, live attenuated vaccine

Background

Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum (S. Pullorum) is the causative agent of Pullorum disease (PD), an acute systemic disease that results in high morbidity and mortality in young chicks and a loss of weight, decreased fertility and hatchability, lesions, diarrhea and abnormalities of the reproductive tract in infected adults, it can be transmitted vertically to chicks through eggs [1]. This disease remains a big threat of restricting the growth of the poultry industry in developing countries [2]. As a close relative of S. Pullorum, Salmonella enterica serovar Gallinarum (S. Gallinarum) causes Fowl typhoid (FT), a severe systemic disease with significant morbidity and mortality in poultry in many countries [2–5].

Vaccination is an effective strategy for the control of Salmonella infections, both humoral and cellular immunity are required for ideal Salmonella vaccines [6]. Live vaccines offer greater protection than killed vaccines because higher cellular immune response could be induced, it is important for clearance of Salmonella infections [6].

As an indispensable virulence determinant associated with the systemic infections, Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI2) can encode type III secretion system 2 (T3SS2), which is induced after invasion, and the T3SS2 secreted effectors are essential for Salmonella to survive and replicate inside various cell types [7, 8]. There are some papers on the vaccine potential of S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium and S. Typhi mutants with deletion of SPI2 or other key genes located within the pathogenicity island display decreased virulence in poultry, pigs, cattle, mice, and humans [9–14]. Therefore, in order to determine whether the SPI2 mutant strain of S. Pullorum has the vaccine potential, we evaluated the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of S06004ΔSPI2 in susceptible HY-line white chickens. Our results showed that intramuscular vaccination with S06004ΔSPI2 provides efficient protection against challenges with S. Pullorum and S. Gallinarum.

Methods

Experimental animals

The animal experiments were conducted with the approval of the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Yangzhou University. HY-line white chicken eggs were hatched and the chickens were detected for freedom from any clinical signs of enteric disease and negative for Salmonella. Two-day old chickens were used in this study and given antibiotic–free food and water throughout the experimental period.

Bacterial strains

S. Pullorum S06004 (accession No. CP006575.1), a nalidixic acid-resistant (Nalr) clinical isolate obtained from chickens with Pullorum disease in the Jiangsu Province of China in 2006 [15], and the virulent wild type S. Gallinarum strain SG9 (Nalr), supplied by Dr. Barrow [16], were used as challenge strains. S06004ΔSPI2 (Nalr, the whole SPI2 (~40 kb) deleted mutant of S. Pullorum S06004), constructed using the one-step inactivation method described by Datsenko and Wanner [17, 18], was used as the vaccine candidate for this study. Bacterial strains were stored as frozen cultures in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth with 20 % glycerol at −70 °C before use. LB broth, LB solid (15 g/L agar) and XLT4 (Difco) agar were used for culturing bacteria at 37 °C. The media were supplemented with Nal (40 μg/ml) as required.

Bacterial inoculation in chickens

One hundred 2-day old chickens were randomly assigned to 2 groups: vaccinated group (n = 45) and control group (n = 55). The vaccinated group was intramuscularly immunized with 2 × 107 CFU S06004ΔSPI2 in 100 μl phosphate buffered saline (PBS), while control group was unimmunized and only received equal amounts PBS.

Changes of body weight and clinical symptoms after vaccination

Body weights of these chickens were measured at 5, 12 and 19 days post vaccination (dpv), and they were monitored for 19 days for clinical signs of disease, which included anorexia, diarrhea and depression, etc.

Bacterial persistence and clearance from internal organs

Liver and spleen samples of five chickens from each group were aseptically collected at 5, 7, 10, 14 and 21 dpv for bacterial recovery. Then they were weighed and suspended in 1 ml PBS and homogenized individually. Homogenates (100 μl) of different dilutions were inoculated on XLT4 agar (containing 40 μg/ml Nal) for enumeration and incubated for 20 h at 37 °C. The bacterial number in the sample was counted and expressed as log10 CFU/g, negative samples were indicated as 0 CFU/g.

Immune responses induced by the vaccine strain

Humoral immune responses were evaluated through determination of Specific antibody IgG levels by Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), using heat-killed whole S. Pullorum bacteria as coating antigen as previously described [19]. Serum samples were collected from five chickens of each group at 3, 7, 14 and 21 dpv, and diluted 1:50 to be used as the primary antibody. The secondary antibody was Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit anti-chicken IgG (1:10,000 dilution). The bound HRP activity was determined using o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma), and the OD492 was determined with an ELISA reader after the reactions were stopped by 2 M H2SO4.

Cellular immune responses were evaluated by the peripheral mononuclear cell proliferation assay as previously described [20, 21]. Soluble antigen was prepared from the wild type S. Pullorum strain S06004. Peripheral lymphocytes were separated from blood of five birds per group using the Histopaque®-1077 (Sigma) at 7, 14 and 21 dpv. After trypan blue dye exclusion testing, a viable mononuclear cell suspension (100 μl) at 1 × 106 CFU/ml in RPMI-1640 medium with 10 % fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 U/ml of penicillin and 50 μg/ml of streptomycin was incubated in triplicate in 96-well tissue culture plates with 50 μl of medium alone or medium containing 4 μg/ml of soluble antigen at 41 °C (in a humidified 5 % CO2 atmosphere for 48 h). The proliferation of stimulated lymphocytes was measured using adenosine triphosphate (ATP) bioluminescence with the ViaLight® Plus Kit (Lonza Rockland, ME, USA). The blastogenic response against soluble antigen was expressed as the mean stimulation index (SI) as previously described [20].

Evaluation of immune protection

Protective efficacy of S06004ΔSPI2 against challenges with S. Pullorum and S. Gallinarum were assessed, based on survival rates and clinical symptoms (including anorexia, diarrhea, depression, high morbidity and mortality). At 10 dpv, twenty chickens from vaccinated group were randomly divided into two groups of 10 animals (group A and C), thirty chickens from control group were randomly divided into three groups of 10 animals (group B, D and E). Group A and B were challenged intramuscularly with 2 × 109 CFU S06004 in 100 μl of PBS. Groups C and D received equal amounts of SG9. Group E only received 100 μl PBS. The surviving birds were counted at 21 days post challenge, and clinical symptoms were recorded every day from 1–35 dpv.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) values unless otherwise specified and analyzed with GraphPad Prism. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant when using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Results

Changes of body weight and clinical symptoms after vaccination

After vaccination with S06004ΔSPI2, the mean body weight of each chicken in vaccinated group and control group at 5, 12 and 19 dpv were shown in Table 1. No significant differences and no clinical signs (anorexia, diarrhea and depression) were observed between the two groups.

Table 1.

Mean body weights of chickens after vaccination. The vaccinated group was intramuscularly immunized with 2 × 107 CFU S06004ΔSPI2 in 2-day old chickens, and control group received 100 μl PBS

| Group | Mean body weight per chicken at dpv (g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 12 | 19 | |

| vaccinated | 65.416 ± 0.418 | 113.878 ± 0.493 | 186.583 ± 0.716 |

| Control | 64.592 ± 0.782 | 114.618 ± 0.795 | 187.171 ± 0.385 |

There were no significant differences between groups at any time point (P > 0.05)

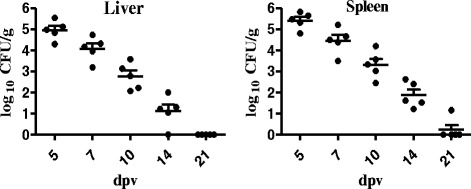

Bacterial persistence and clearance in internal organs

All liver and spleen samples of control group were negative for Salmonella recovery. As shown in Fig. 1, the considerably decreased bacterial counts of vaccinated group were continuously observed through to 21 dpv in both liver and spleen, but S06004ΔSPI2 bacteria can colonize and persistent in liver and spleen of vaccinated chickens approximately 14 days. Only one spleen sample was positive and no liver sample was positive at 21 dpv.

Fig. 1.

Bacterial recovery from liver and spleen of the vaccinated chickens. The vaccinated group was intramuscularly immunized with 2 × 107 CFU S06004ΔSPI2 in 2-day old chickens, and control group received 100 μl PBS. Values represent the mean ± SEM log10 CFU/g. All liver and spleen samples of control group were negative

Humoral and cellular immune responses

Humoral immune responses were evaluated by measuring specific serum IgG levels at 3, 7, 14 and 21 dpv using ELISA. The mean OD492 values of vaccinated group were 0.221 ± 0.019, 0.484 ± 0.039, 0.678 ± 0.056 and 1.032 ± 0.064 at 3, 7, 14 and 21 dpv, respectively (Fig. 2). The chickens in vaccinated group had significantly higher serum IgG levels than those in control group at 7, 14 and 21 dpv. The considerably elevated serum IgG levels of vaccinated group were continuously observed through to 21 dpv.

Fig. 2.

Determination of serum IgG levels. Vaccinated group and control group refer to Fig. 1. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *Significant difference compared to the control group, P < 0.05

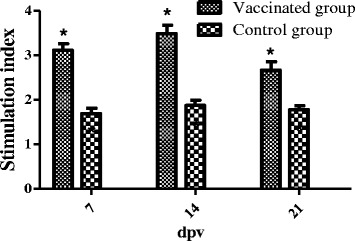

Cellular immune responses were examined by the peripheral mononuclear cell proliferation assay. The mean SI values of vaccinated group were 3.124 ± 0.138, 3.495 ± 0.188 and 2.667 ± 0.189 at 7, 14 and 21 dpv, respectively (Fig. 3). All tested chickens in vaccinated group revealed considerably elevated SI values compared to control group, and the significantly elevated SI values was continuously observed at 14 dpv, but was reduced at 21 dpv.

Fig. 3.

Stimulation index (SI) of chicken lymphocyte samples determined by peripheral lymphocyte proliferation assay using soluble antigen. Vaccinated group and control group refer to Fig. 1. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *Significant difference compared to the control group, P < 0.05

Immune protection

The percent survival of chickens which had been vaccinated intramuscularly with S. Pullorum mutant S06004ΔSPI2 followed by challenge with the parent S. Pullorum strain S06004 or S. Gallinarum strain SG9 at 10 dpv was shown in Table 2. One immunized chicken died, whereas nine chickens died in control group B after challenged with S06004. Three immunized chickens died, whereas all ten chickens died in control group D after challenged with SG9. The clinical symptoms (high morbidity and mortality, anorexia, diarrhea, depression) of group A and C were slight and temporary after challenged compared to group E, and the chickens had recovered by 3–7 days post challenge; but these clinical symptoms were observed in group B and D. S06004ΔSPI2 conferred effective protection.

Table 2.

Protective efficacy of S06004ΔSPI2. Group A and C were intramuscularly immunized with 2 × 107 CFU S06004ΔSPI2 in 2-day old chickens, group B, D and E were nonimmunized. At 10 dpv, group A–D were challenged

| Group | Vaccination | Number | Challenge | Survivors/Total | Survival rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Strain | Route | Dose (CFU) | ||||

| A | S06004△SPI2 | 10 | S06004 | intramuscularly | 2 × 109 | 9/10 | 90* |

| B | PBS | 10 | S06004 | intramuscularly | 2 × 109 | 1/10 | 10 |

| C | S06004△SPI2 | 10 | SG9 | intramuscularly | 2 × 109 | 7/10 | 70* |

| D | PBS | 10 | SG9 | intramuscularly | 2 × 109 | 0/10 | 0 |

| E | PBS | 10 | — | — | — | 10/10 | 100 |

*P < 0.05 for comparison of group A with group B, and group C with group D

Discussion

In this work, we evaluated the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI2) deleted mutant of S. Pullorum (S06004ΔSPI2) to serve as a live vaccine against PD and FT in susceptible HY-line white chickens on the basis of changes of body weight and clinical symptoms, bacterial persistence and clearance, humoral and cellular immune responses, and protective efficiency.

In order to evaluate the effects of S06004ΔSPI2 on growth performance in chickens, we recorded the body weight increases and observed the clinical symptoms after intramuscular vaccination. Our results showed that S06004ΔSPI2 has almost no side effects on growth performance in chickens. T3SS2 encoded by SPI2 is essential for Salmonella colonization and persistence in host. With the absence of a functional T3SS2, Salmonella is cleared more rapidly than the parental wild type strain from the host, and some studies have failed to isolate SPI2 mutants from liver and spleen after oral inoculation [5, 16, 22]. Here, our results showed that S06004ΔSPI2 can colonize and persist in liver and spleen of vaccinated chickens approximately 14 days, this may be related to the breed of chicken, the routes of vaccination and the dose of inoculation.

Specific humoral and cellular immune responses induced by the live attenuated vaccines of Salmonella are crucial for the natural host [6]. To investigate the specific humoral immune responses imparted by the candidate, we examined the specific serum IgG antibody level by indirect ELISA, there was a strong specific serum IgG level in vaccinated chickens, and the antibodies were detectable at 7 dpv. The vaccinated chickens showed significantly elevated IgG levels compared to non-immunized chickens. S. Enteritidis SPI2 mutant can also induce significant increase of antibodies in chickens [9]. Cellular immune responses play a central role in protection against Salmonella challenge, because Salmonella are facultative intracellular pathogens [23]. We further evaluated the cellular immune responses imparted by the candidate in chickens using the peripheral lymphocyte proliferation assay. In the present study, a significantly elevated cellular immune response was clearly observed in chickens immunized with S06004ΔSPI2, but the significantly elevated SI value was decreased at 21 dpv, it is related to the restricted colonization of bacteria in internal organs [24, 25]. Taken together, the specific humoral and cellular immune responses were clearly observed in the vaccinated chickens in this study.

Several previous reports have shown that live attenuated Salmonella vaccines can confer effective cross-protection to different pathogenic Salmonella serovars [26, 27]. Here, we evaluated the protective efficacy of the candidate vaccine against challenge intramuscularly with S. Pullorum and S. Gallinarum, respectively, based on survival rates and clinical symptoms in HY-line white chickens. The survival rates were 90 % and 70 % following respective challenge with S. Pullorum and S. Gallinarum in vaccinated chickens; but in the control groups, the survival rates were 10 % and 0, respectively. The light and temporary clinical symptoms of vaccinated chickens (group A and C) had recovered by 3–7 days post-challenge. Recently, our results also showed that S06004ΔSPI2 can be used as a live attenuated oral vaccine [28]. Overall, these results showed that the candidate vaccine S06004ΔSPI2 can afford effective protection for acute systemic PD and FT infection.

Conclusions

Our present work demonstrated that the vaccination of susceptible chickens with the candidate vaccine S06004ΔSPI2 conferred development of acquired immunity and efficient protection for the experimental systemic PD and FT infection. Taken together, the SPI2 mutant strain of S. Pullorum has the potential of being used as a safe, novel, highly immunogenic vaccine against PD and FT.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31230070), Colleges and Universities of Jiangsu Province Plans to Graduate Research and Innovation (CXZZ13_0917), National Science & Technology Pillar Program (2014BAD13B02), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31201905), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Abbreviations

- S. Pullorum

Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum

- S. Gallinarum

Salmonella enterica serovar Gallinarum

- PD

Pullorum disease

- FT

Fowl typhoid

- SPI2

Salmonella pathogenicity island 2

- T3SS2

Type III secretion system 2

- Dpv

Days post vaccination

- LB

Luria-Bertani

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- SI

Stimulation index

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XJ, QL and JY designed the experiments, SG and ZP conducted experiments, JY, ZC and LX performed the experiments, JY and ZC analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript, XJ finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Rettger LF. Further Studies on fatal Septicemia in Young Chickens, or "White Diarrhea.". J Med Res. 1909;21:115–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrow PA, Freitas Neto OC. Pullorum disease and fowl typhoid--new thoughts on old diseases: a review. Avian Pathol. 2011;40:1–13. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2010.542575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Smith NH, Nelson K, Crichton PB, Old DC, Whittam TS, Selander RK. Evolutionary origin and radiation of the avian-adapted non-motile salmonellae. J Med Microbiol. 1993;38:129–39. doi: 10.1099/00222615-38-2-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumler AJ, Tsolis RM, Ficht TA, Adams LG. Evolution of host adaptation in Salmonella enterica. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4579–487. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4579-4587.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wigley P, Berchieri A, Jr, Page KL, Smith AL, Barrow PA. Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum persists in splenic macrophages and in the reproductive tract during persistent, disease-free carriage in chickens. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7873–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7873-7879.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mastroeni P, Chabalgoity JA, Dunstan SJ, Maskell DJ, Dougan G. Salmonella: immune responses and vaccines. Vet J. 2001;161:132–64. doi: 10.1053/tvjl.2000.0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galan JE. Salmonella interactions with host cells: type III secretion at work. Annu Rev Cell Dev Bi. 2001;17:53–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waterman SR, Holden DW. Functions and effectors of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:501–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matulova M, Havlickova H, Sisak F, Rychlik I. Vaccination of chickens with Salmonella Pathogenicity Island (SPI) 1 and SPI2 defective mutants of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. Vaccine. 2012;30:2090–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan SA, Stratford R, Wu T, McKelvie N, Bellaby T, Hindle Z, et al. Salmonella typhi and S. typhimurium derivatives harbouring deletions in aromatic biosynthesis and Salmonella Pathogenicity Island-2 (SPI-2) genes as vaccines and vectors. Vaccine. 2003;21:538–48. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyen F, Pasmans F, Van Immerseel F, Morgan E, Botteldoorn N, Heyndrickx M, et al. A limited role for SsrA/B in persistent Salmonella Typhimurium infections in pigs. Vet Microbiol. 2008;128:364–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coombes BK, Coburn BA, Potter AA, Gomis S, Mirakhur K, Li Y, Finlay BB. Analysis of the contribution of Salmonella pathogenicity islands 1 and 2 to enteric disease progression using a novel bovine ileal loop model and a murine model of infectious enterocolitis. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7161–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7161-7169.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dieye Y, Ameiss K, Mellata M, Curtiss R., 3rd The Salmonella Pathogenicity Island (SPI) 1 contributes more than SPI2 to the colonization of the chicken by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karasova D, Sebkova A, Havlickova H, Sisak F, Volf J, Faldyna M, et al. Influence of 5 major Salmonella pathogenicity islands on NK cell depletion in mice infected with Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geng S, Jiao X, Barrow PA, Pan Z, Chen X. Virulence determinants of Salmonella Gallinarum biovar Pullorum identified by PCR signature-tagged mutagenesis and the spiC mutant as a candidate live attenuated vaccine. Vet Microbiol. 2014;168:388–94. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones MA, Wigley P, Page KL, Hulme SD, Barrow PA. Salmonella enterica serovar Gallinarum requires the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system but not the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 type III secretion system for virulence in chickens. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5471–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5471-5476.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6640–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin J, Wu Y, Lin Z, Wang X, Hu Y, Li Q, et al. Construction and characterization of SPI-2 deletion mutant of Salmonella Pullorum S06004. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao. 2015; 10.13343/j.cnki.wsxb.20140621. [PubMed]

- 19.Haneda T, Okada N, Kikuchi Y, Takagi M, Kurotaki T, Miki T, et al. Evaluation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Choleraesuis slyA mutant strains for use in live attenuated oral vaccines. Comp Immunol Microbiol. 2011;34:399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rana N, Kulshreshtha RC. Cell-mediated and humoral immune responses to a virulent plasmid-cured mutant strain of Salmonella enterica serotype gallinarum in broiler chickens. Vet Microbiol. 2006;115:156–62. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song H, Yan R, Xu L, Song X, Shah MA, Zhu H, Li X. Efficacy of DNA vaccines carrying Eimeria acervulina lactate dehydrogenase antigen gene against coccidiosis. Exp Parasitol. 2010;126:224–31. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cirillo DM, Valdivia RH, Monack DM, Falkow S. Macrophage-dependent induction of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system and its role in intracellular survival. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:175–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins FM, Scott MT. Effect of Corynebacterium parvum treatment on the growth of Salmonella enteritidis in mice. Infect Immun. 1974;9:863–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.9.5.863-869.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuda K, Chaudhari AA, Lee JH. Evaluation of safety and protection efficacy on cpxR and lon deleted mutant of Salmonella Gallinarum as a live vaccine candidate for fowl typhoid. Vaccine. 2011;29:668–74. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wigley P, Jones MA, Barrow PA. Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum requires the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system for virulence and carriage in the chicken. Avian Pathol. 2002;31:501–6. doi: 10.1080/0307945021000005879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heithoff DM, House JK, Thomson PC, Mahan MJ. Development of a Salmonella cross-protective vaccine for food animal production systems. Vaccine. 2015;33:100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nandre RM, Lee D, Lee JH. Cross-protection against Salmonella Typhimurium infection conferred by a live attenuated Salmonella Enteritidis vaccine. Can J Vet Res. 2015;79:16–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin J, Cheng Z, Wang X, Xu L, Li Q, Geng S, Jiao X. Evaluation of Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum pathogenicity island 2 mutant as a candidate live attenuated oral vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015;22:706–10. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00130-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]