Abstract

Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Masson's tumor) is a benign lesion of the skin and subcutaneous tissue consisting of a reactive proliferation of endothelial cells with papillary formations related to a thrombus. It poses a diagnostic challenge as the clinical signs and symptoms are nonspecific and may mimic a soft tissue sarcoma. The diagnosis is based on histopathology. Here we report two cases of Masson's hemangioma occurring on the upper lip and on the left hand.

Keywords: Hemangioma, intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia, thrombus

INTRODUCTION

In 1923, Pierre Masson first described an intravascular papillary proliferation formed within the lumen of inflamed hemorrhoidal plexus in a man and named it “Hemangioendotheliome vegetant intravasculaire.”[1] From the time of its initial description it has been referred to by various eponyms, including Masson's tumor, Masson's hemangioma, Masson's intravascular hemangioendothelioma, intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (IPEH) or reactive papillary endothelial hyperplasia.[2] Masson described it to be a form of neoplasm and explained the pathogenesis as proliferation of endothelial cells into the vessel lumen, followed by obstruction and secondary degeneration and necrosis. On the other hand, Henschen[3] depicted the lesion as a reactive process rather than a neoplasm. Kauffman and Stout[3] remarked that, although endothelial proliferation that can be easily mistaken for a characteristic of sarcoma is present, the endothelial layer of the lesion is composed of normal endothelial cells, the endothelial proliferation is of benign papillae pattern and the cells show no atypia. However, it is now believed to be a reactive vascular proliferation following traumatic vascular stasis, and the current terminology, IPEH, was proposed by Clearkin and Enzinger[2] in 1976. It is a rare benign condition mimicking angiosarcoma and hence it is being reported here.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 25-year-old female presented with a firm, painless, bluish, slow growing lesion in the upper lip, which was clinically diagnosed as papilloma. Excision of the mass was done and sent for histopathology examination. The H and E sections showed a dilated vessel with an organized thrombus and numerous papillae with a connective tissue core, lined by a single layer of endothelial cells with no atypia, necrosis and mitosis. The lesion was well-circumscribed and contained inside the vascular wall. Thus malignancy was excluded and a diagnosis of IPEH (Masson's hemangioma) of the lip [Figures 1 and 2] was made.

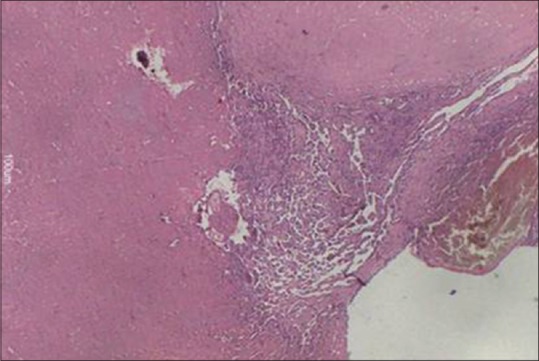

Figure 1.

The lesion showing an organizing thrombus in a dilated vessel accompanied by a papillary formation (H and E, ×100)

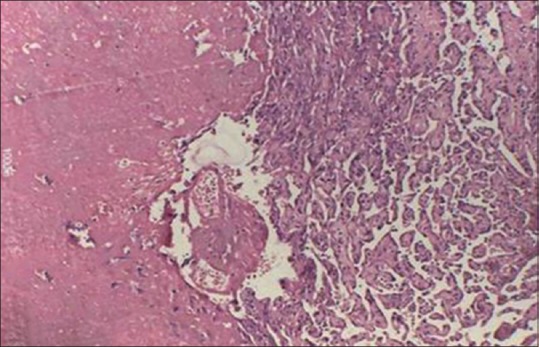

Figure 2.

Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. A thrombus and papillae lined by single layer of benign endothelial cells (H and E, ×400)

Case 2

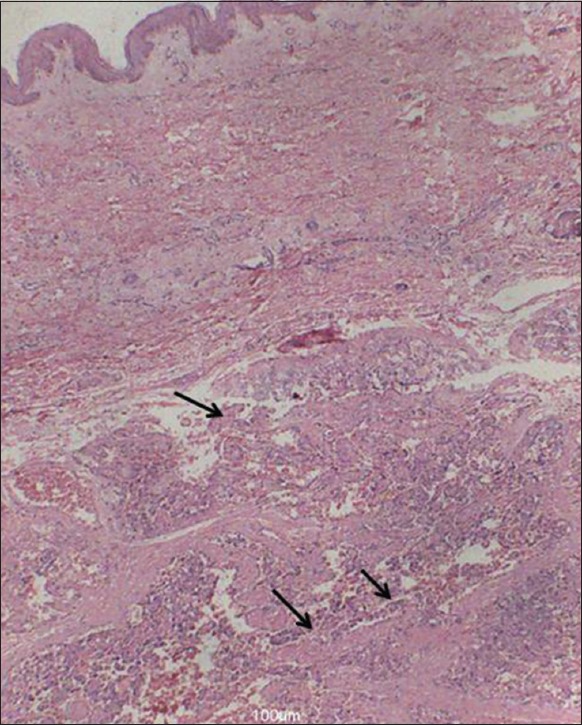

A 31-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with the complaint of swelling on his left hand. Clinically it was a firm, smooth, round and slightly painful swelling. Biopsy was done and H and E sections revealed under a normal stratified squamous epithelium, a well-circumscribed lesion with multiple small papillary structures, [Figure 3] covered by a single layer of endothelium with no atypia. Some of the papillae were attached to the vascular wall and others were lying free in the lumen. Absence of mitotic figures, necrosis, nuclear pleomorphism, and infiltration into adjacent tissue, ruled out malignancy in this case. Abutting to these papillae were areas which showed cystically dilated thin walled vessels filled with blood [Figure 3]. Thus a diagnosis of IPEH superimposed on a cavernous hemangioma (secondary Masson's hemangioma) was given.

Figure 3.

The lesion is well-circumscribed with multiple small papillary structures (arrows) and abutting to the papillae are dilated blood vessels (cavernous hemangioma). Overlying epithelium is also seen (H and E, ×100)

DISCUSSION

Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia is a reactive proliferative lesion of endothelial cells in blood vessels. It is an unusual lesion constituting about 2% of the benign and malignant vascular tumors of the skin and subcutaneous tissues.[4] IPEH may occur in any part of the body and there is a predilection for the deep dermis and subcutis of the head, neck, fingers and trunk. It usually presents as a small, firm, superficial mass with red to blue discoloration of the overlying skin.[5] However, the occurrence of IPEH in the oral cavity is extremely rare. A review in the accessible literature showed <80 cases of IPEH in the oral mucosa and lips.[3] Deep-seated IPEH of the extremities arising from preexisting, intramuscular, cavernous hemangiomas, are considered to be very rare. We report these two cases of Masson's hemangioma because of their rare location - the lip and the forearm. The latter site was associated with cavernous hemangioma, a rare variant of IPEH.

There is no gender or age predilection and it has been equally reported in males and females. However, Pins et al. reported a female: male ratio of 1.2:1.0 with an average age of presentation of 34 years.[6]

Two theories have been proposed to account for the pathogenesis of this lesion. The first theory originally proposed by Masson, states that endothelial proliferation is the primary phenomenon whereas the thrombus arises secondary to endothelial proliferation.[2] In contrast, Clearkin and Enzinger in 1976 suggested that this papillary structure appears after a preexisting thrombus organizes. Nowadays, it is considered to be a reactive vascular proliferation following traumatic vascular stasis. The pathogenesis of IPEH might be related to inflammation or mechanical stimulus such as irritation. It has been proposed that IPEH formation is triggered off with release of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF) by the invading macrophages to the trauma site with proliferation of endothelial cells. Further release of more basic FGF by the proliferating endothelial cells occur, cascading into a positive feedback of endothelial cell proliferation.[7]

Three clinical types of this lesion have been described.[8] A primary or “pure” form arises within a normal blood vessel, most commonly a vein, and is often sited on the fingers, head and neck, and forearms. Our first case that originated in a blood vessel of the lip without any secondary lesion was of the above type. The secondary lesion or “mixed” form arises in the setting of a preexisting vascular malformation, such as a hemorrhoidal vein, cavernous hemangioma or pyogenic granuloma and may be sited intramuscularly. Our second case belonged to this category as it originated in a cavernous hemangioma. The rarest type, an extravascular hemangioma, usually arises from an organizing hematoma.

Microscopy is very important for its diagnosis. IPEH consists of an intravascular proliferation of numerous papillae with a core of connective tissue and an endothelial surface. It can be distinguished from other neoplastic lesions because it is frequently well-circumscribed or encapsulated, with characteristic papillary fronds, and the proliferative process is entirely limited by the vascular wall[2] as seen in both of our cases. A major differential of IPEH is angiosarcoma. The papillary structure and exuberant endothelisation of IPEH necessitates ruling out the much more frequent angiosarcoma. The following features are important in the differential diagnosis: (a) IPEH is often well-circumscribed or encapsulated; (b) the proliferative process is completely limited to the intravascular spaces; (c) though the endothelial cells are hyperchromatic, extreme nuclear atypia and frequent mitotic figures cannot be seen; (d) papillae are composed of fibrohyalinized tissue of two or more endothelial cell layers without any covering; (e) there is no true endothelial confirmation of IPEH; (f) tangential sectioning may reveal pseudochannels, but no irregular or anastomosing blood vessels in the stroma; and (g) necrosis is an unusual finding in IPEH.[9]

However angiosarcoma invades tissues outside the vascular channels and has more than one or two layers of endothelial cells covering the papillary formation. It also shows more malignant features on cytology,[10] such as mitotic figures, necrosis, nuclear pleomorphism, and infiltration into adjacent tissue.

Immunohistochemical confirmation may be required only if the endothelial origin of the lesion is in question. In such cases endothelial cell markers, such as von Willebrand factor, CD31, factor XIIIa, and CD43 may be used, which would highlight the endothelial lining around the papillary tufts. The treatment for IPEH is surgical excision with complete resection.[11]

The importance of IPEH or Masson's hemangioma lies in the fact that it histologically simulates angiosarcoma. Moreover, it tends to recur if incompletely resected. Correct diagnosis of this entity is essential to prevent aggressive treatment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yücesoy C, Coban G, Yilmazer D, Oztürk E, Hekimoglu B. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Masson's hemangioma) presenting as a lateral neck mass. JBR-BTR. 2009;92:20–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fasina O, Adeoye A, Akang E. Orbital intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia in a Nigerian child: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:300. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narwal A, Sen R, Singh V, Gupta A. Masson's hemangioma: A rare intraoral presentation. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013;4:397–401. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.118363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amérigo J, Berry CL. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia in the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1980;387:81–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00428431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park SJ, Kim HJ, Park SH, Yeo UC, Lee ES. A case of intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia on upper lip. Korean J Dermatol. 2000;38:1693–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pins MR, Rosenthal DI, Springfield DS, Rosenberg AE. Florid extravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Masson's pseudoangiosarcoma) presenting as a soft-tissue sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117:259–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levere SM, Barsky SH, Meals RA. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia: A neoplastic “actor” representing an exaggerated attempt at recanalization mediated by basic fibroblast growth factor. J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19:559–64. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(94)90256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashimoto H, Daimaru Y, Enjoji M. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. A clinicopathologic study of 91 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:539–46. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farah JM, Sawke N, Sawke GK. Cutaneous intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia of the forearm: A case report. Peoples J Sci Res. 2013;6:38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shields JA, Shields CL, Eagle RC, Jr, Diniz W. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia with presumed bilateral orbital varices. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1247–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar A, Surowiec S, Nigwekar P, Illig KA. Masson's intravascular hemangioma masquerading as effort thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:812–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]