Abstract

Objective

We investigate differences between White and South Asian (SA) populations in levels of objectively measured and self-reported physical activity.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Leicestershire, UK, 2010–2011.

Participants

Baseline data were pooled from two diabetes prevention trials that recruited a total of 4282 participants from primary care with a high risk score for type 2 diabetes. For this study, 2843 White (age=64±8, female=37%) and 243 SA (age=58±9, female=34%) participants had complete physical activity data and were included in the analysis.

Outcome measures

Moderate-intensity to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) and walking activity were measured using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), and a combination of piezoelectric pedometer (NL-800) and accelerometer (Actigraph GT3X) were used to objectively measure physical activity.

Results

Compared to White participants, SA participants self-reported less MVPA (30 vs 51 min/day; p<0.001) and walking activity (11 vs 17 min/day; P=0.001). However, there was no difference in objectively measured ambulatory activity (5992 steps/day vs 6157 steps/day; p=0.75) or in time spent in MVPA (18.0 vs 21.5 min/day; p=0.23). Results were largely unaffected when adjusted for age, sex and social deprivation. Compared to accelerometer data, White participants overestimated their time in MVPA by 51 min/day and SA participants by 21 min/day.

Conclusions

SA and White groups undertook similar levels of physical activity when measured objectively despite self-reported estimates being around 40% lower in the SA group. This emphasises the limitations of comparing self-reported lifestyle measures across different populations and ethnic groups.

Trial registration number

Reports baseline data from: Walking Away from Type 2 Diabetes (ISRCTN31392913) and Let's Prevent Diabetes (NCT00677937).

Keywords: SPORTS MEDICINE, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Self-reported measures of physical activity have numerous limitations, which may contribute to reported differences between ethnic groups.

Using data from two large studies, physical activity levels between South Asian (SA) populations and the general population were similar when using objective measures of movement.

Despite the similarity between ethnic groups with objective measures, large differences were found with a commonly used self-reported measure of physical activity where SA participants reported around 20 min less physical activity per day than the general population.

The major strength of this study is the use of both objective and self-reported measures of physical activity, which highlights how reliance on self-report may exaggerate differences between ethnic groups.

The population included in this study was identified with a high risk of type 2 diabetes and there was some missing data, which may act to limit generalisability.

Introduction

In the UK and other industrialised countries, individuals from South Asian (SA) populations are known to have substantially higher rates of chronic disease, particularly type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.1 Differences in health behaviours, such as physical activity, have been reported to be an important determinant of this increased risk.1 2 For example, SA and other minority ethnic groups have consistently been shown to undertake as little as half the amount of daily physical activity as the majority White population in the UK and USA.3–6 In the UK, it has been estimated that differences in self-reported physical activity between SA and White ethnic groups account for over 20% of the excess risk of CHD mortality in the SA sample.2 However, studies investigating ethnic-specific differences in physical activity have relied on self-reported measures of behaviour, which are relatively easy and inexpensive to administer. Self-reported measures of physical activity have inherent limitations, which are likely to be exacerbated when used to compare health behaviour across populations. For example, the way in which physical activity is conceptualised and reported is likely to be heavily influenced by cultural factors beyond total physical activity volume. Many of these limitations can be overcome by employing objective measures of physical activity, such as through the use of pedometers or accelerometers.7 The aim of this study was to investigate and compare levels of self-reported and objectively assessed physical activity in a White and SA group. In addition, we investigated whether validity estimates for the self-reported measures differ across ethnic groups.

Methods

This study reports baseline data from the Walking Away from Type 2 Diabetes and Let's Prevent Diabetes trials. Both studies are ongoing concurrently within primary care, Leicestershire, UK. The design of both studies and baseline profile of recruited participants has been described in detail previously.8–10 Both studies underwent National Health Service (NHS) ethical review; written consent was obtained for each participant.

Walking Away: 833 adults were recruited from 10 general practices, 2010–2011.8 Individuals were included on the basis of having a high risk of impaired glucose regulation (IGR) (composite of impaired glucose tolerance and/or impaired fasting glycaemia) or undiagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus identified using a modified version of the automated Leicester Risk Score, specifically designed to be administered in primary care.10 11 An automated platform using medical records was used to rank individuals for diabetes risk using predefined weighted variables (age, gender, body mass index (BMI), family history of type 2 diabetes and use of antihypertensive medication). Those scoring within the 90th centile in each practice were invited to attend a screening visit and to take part in the study. All those who were screened and did not have diabetes were included in a randomised controlled trial testing the effectiveness of a structured education programme designed to promote increased walking activity.8

Let's Prevent Diabetes: 3449 adults were recruited from 44 general practices, 2010–2011.9 As with Walking Away, individuals were recruited on the basis of scoring within the 90th centile of the automated Leicester Risk Score (described above). Those confirmed to have IGR were invited to continue into a randomised controlled trial testing the effectiveness of a structured education programme designed to promote increased walking activity, a healthy diet and weight loss.

Ethnicity and social deprivation

In both studies, information on ethnicity was obtained following an interview-administered protocol with a healthcare professional. Participants classified themselves into 1 of 16 ethnic groups including White (British, Irish or other), Asian or Asian British (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi or other), and Black or Black British (Caribbean, African or any other Black background). Social deprivation was determined by assigning an Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score to the participant's resident area.12 IMD scores are publically available continuous measures of compound social and material deprivation that are calculated using a variety of data including current income, employment, education and housing.

Physical activity

International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ; both studies)

Self-reported total moderate-intensity to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) and walking activity were measured using the short past 7 days self-administered format of IPAQ.13 IPAQ has been internationally validated, and measures the frequency and duration of any walking, other moderate or vigorous-intensity physical activity undertaken for more than 10 continuous minutes across all contexts (eg, work, home and leisure) over a 7-day period.13 Total time in MVPA per day was determined by summing weekly time in walking, moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity activity, and dividing by 7.

Accelerometer (Walking Away only)

Participants were asked to wear a tri-axial accelerometer (Actigraph GT3X, Florida, USA) on the right mid-axillary line of the hip (attached via a waistband), for seven consecutive days during waking hours. These accelerometers translate raw accelerations into activity counts. The accelerometers were initialised to record activity in 15 s epochs. However, to allow for valid comparisons against the IPAQ, which assesses non-sporadic activity, data were reintegrated into 60 s epochs. Freedson cut-points were used to categorise MVPA (≥1952 counts per minute).14 We also derived the time spent in bouts of at least 10 min of MVPA; a 10 min bout was defined as 10 or more consecutive minutes above the moderate intensity activity count threshold, with allowance for interruptions of two 60 s epochs below the moderate threshold. Total physical activity (movement) was computed using accelerometer-defined counts over the full period of valid data collection. Similarly, ambulatory activity was measured using steps, which are also a function on the GT3X accelerometer.

Non-wear time was defined as a minimum of 60 min of continuous zero counts, and days with at least 600 min wear time were considered valid. In order for data to be included in the analysis, participants required at least four valid days.15 Physical activity variables were reported as average daily values derived by dividing total valid outputs by days worn.

A physical activity data analysis tool (ActiSCi, Suffolk, UK) was used to derive wear time, apply cut-point activity categories and undertake reintegration of epoch lengths (15–60 s).

Pedometer (Let's Prevent only)

Piezoelectric pedometers with a 7-day memory (NL-800, New-lifestyles, USA) were used to measure ambulatory activity. New-lifestyles pedometers have been shown to have excellent reliability and validity, and are more accurate than spring-levered pedometers for use on overweight and obese individuals.16 17 All participants were fitted with a pedometer (placed on their trunk along the right anterior axillary line) and instructed to wear it during waking hours for seven consecutive days and to keep a daily log of the time the instrument was attached in the morning and taken-off in the evening. At least three valid days of data were required; a valid day constituted at least 10 h of wear time as assessed by the pedometer log. It has been shown that the average steps per day of any weekly 3-day combination are highly correlated (r>0.8) with the average steps per day taken over a full 7-day period;18 consequently, three or more days of data provide an acceptable measure of habitual walking activity.

Data analysis

This study reports data on those identifying themselves as White, Asian or Asian British; other ethnic groups were not adequately represented and were excluded from analysis. Asian or Asian British participants are referred to as SA throughout. Only those with complete physical activity data were included.

Given that the recruitment strategy and standard operating procedures were consistent across studies, IPAQ data were combined. Furthermore, as the instruments used to measure steps/day in Walking Away (accelerometer) and Let's Prevent (pedometer) both used piezoelectric technology and have been shown to have similar high levels of accuracy in the measurement of steps undertaken,19 in addition to the fact that the average estimates were similar across studies (Walking Away median=6324 steps/day (IQR=4501, 8441); Let's Prevent median=6099 steps per day (IQR=4342, 8159)), the measure of ambulatory activity was also combined across studies. This approach was followed with a sensitivity analysis (see below).

Differences in levels of physical activity between ethnic groups were determined using independent T Tests; Mann-Whitney tests were used for non-parametric variables. Linear regression models were used to assess whether differences between ethnic groups were affected when adjusted for basic demographic variables (age, sex and social deprivation). As data for self-reported MVPA were highly skewed and remained so after transformation techniques were applied, adjusted analysis was conducted through a Poisson regression model. Results were analysed for the full cohort and stratified by sex. Stratified results are only reported for the self-reported data and objectively measured ambulatory activity, given the small number of SA individuals with accelerometer data in Walking Away.

The ability of IPAQ to accurately rank participants’ physical activity levels compared to objective measures was assessed using Spearman correlation coefficients. The validity of IPAQ in the Walking Away study was further assessed using Bland-Altman plots for the 1 and 10 min bout definitions of accelerometer derived MVPA.

All analyses were two-sided, p<0 0.05 was considered significant, and carried out on PASW Statistics V.18 (SPSS, http://www.spss.com). Analysis was conducted in 2012.

Sensitivity analysis

We investigate whether differences in self-reported activity between ethnic groups were maintained after those reporting 0 min of MVPA/week were excluded; the prevalence of zero MVPA could potentially be affected by differences in the ability to understand the questionnaire. In addition, self-reported physical activity and objectively measured ambulatory activity results were stratified by study group in order to investigate whether the same pattern of results occurred across both studies.

Results

Overall, 605 (73%) participants from Walking Away and 2481 (72%) participants from Let's Prevent were classified as either White or SA, and had complete self-reported and valid objective measures of physical activity. We report data for these White and SA participants with complete physical activity data. In Walking Away, those with missing data, and therefore excluded, were younger (excluded=60.6±8.8 years, included=64.2±7.5 years) and more likely to be SA (excluded=12%, included=7%); however, there was no difference in sex or social deprivation between those with missing and those with complete data. For Let's Prevent, those with missing data were younger (excluded=62.3±8.7 years, included=63.7±7.7 years), more likely to be female (excluded=42%, included=37%) and from a SA background (excluded=19%, included=8%), although there was no difference in social deprivation.

The age, sex, level of social deprivation and BMI of included participants from both studies are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Walking Away |

Let's Prevent |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | White (n=561) | South Asian (n=44) | White (n=2282) | South Asian (n=199) |

| Sex (female) | 195 (35) | 15 (34) | 859 (38) | 68 (34) |

| Age (years) | 64.7 (7.1) | 58.1 (9.8) | 64.1 (7.4) | 58.5 (9.3) |

| Social deprivation score | 12.5 (8.1, 21.2) | 22.6 (12.5, 29.3) | 11.0 (7.0, 19.0) | 24.0 (13.0, 34.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.0 (5.0) | 29.7 (4.6) | 32.2 (5.5) | 30.1 (5.9) |

Categorical results as number (column percentage), continuous parametric results as mean (SD) and continuous non-parametric results as median (IQR).

BMI, body mass index.

Table 2 shows levels of different physical activity constructs across White and SA groups by self-reported and objective measurements. Self-reported physical activity was substantially different across ethnic groups, with SA participants’ reporting levels of MVPA and walking activity around 35–40% lower than White participants (p≤0.001 for both measures). In contrast, there were no significant differences between the two ethnic groups in any of the physical activity constructs measured objectively, although differences in total number of MVPA minutes neared significance (p=0.06). Differences in self-reported MVPA and walking time remained when stratified by sex (see online supplementary resource 1). Objectively measured ambulatory activity was lower in SA females (5252 steps/day; IQR 3927, 7241) compared to White females (5626 steps/day; IQR 4064, 7503), there was no ethnic difference in males (see online supplementary resource 1).

Table 2.

Self-reported and objectively assessed physical activity data, stratified by ethnic group

| Variable | White | South Asian | Unadjusted p value | Adjusted p value (adjusted for age, sex and social deprivation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported data | ||||

| Walking (mins/day)* | 17 (0, 60) | 11 (0, 40) | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total MVPA (mins/day)* | 51 (4, 124) | 30 (0, 79) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Objective data | ||||

| Ambulatory activity (steps/day)* | 6157 (4372, 8171) | 5992 (4351, 8422) | 0.75 | 0.15 |

| Moderate to vigorous intensity (mins/day)† | 21.5 (10.5, 41.6) | 18.0 (7.5, 36.1) | 0.23 | 0.06‡ |

| Time in MVPA bouts (mins/week)† | 28.0 (0, 101.2) | 17.3 (0, 134.4) | 0.54 | 0.80‡ |

Data as median (IQR).

*Data for the combined Walking Away and Let's Prevent cohorts.

†Data available for the Walking Away study only.

‡Model additionally adjusted for accelerometer wear time.

MVPA, moderate-intensity to vigorous-intensity physical activity.

Table 3 shows the correlations between self-reported and objectively measured physical activity stratified by ethnic group. Correlation coefficients ranged from weak to moderate (ρ=0.17–0.50). Correlation coefficients tended to be stronger in SA participants compared to White participants.

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients between self-reported and objectively assessed physical activity data, stratified by ethnic group

| Ambulatory activity (steps/day) | p Value | Accelerometer derived total MVPA (min/day)* | p Value | Accelerometer derived MVPA in at least 10 min bouts (min/week)* | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White group | ||||||

| Self-reported MVPA (min/day) | 0.25 | <0.001 | 0.35 | <0.001 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Self-reported walking (min/day) | 0.17 | <0.001 | 0.34 | <0.001 | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| SA group | ||||||

| Self-reported MVPA (min/day) | 0.31 | <0.001 | 0.47 | 0.001 | 0.50 | 0.001 |

| Self-reported walking (min/day) | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.46 | 0.001 | 0.49 | 0.001 |

*Data available for the walking away study only.

MVPA, moderate-intensity to vigorous-intensity physical activity.

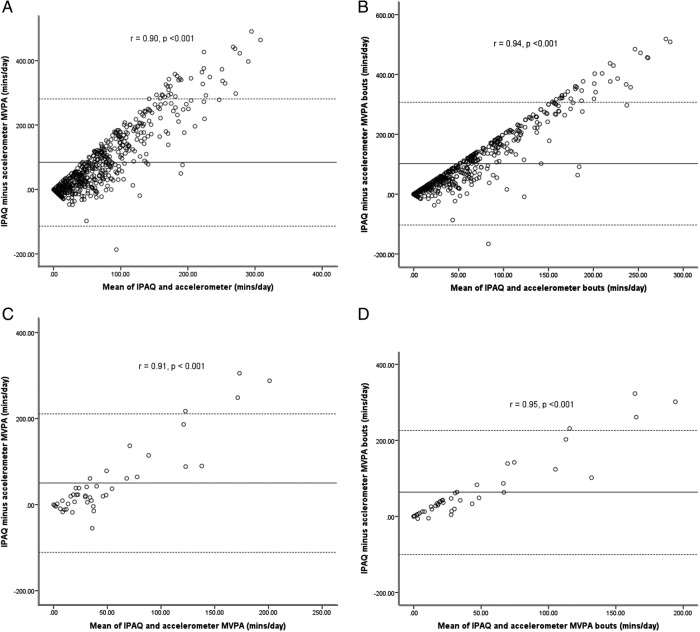

Figure 1 shows Bland-Altman plots, stratified by ethnic group, for time spent in MVPA as assessed by IPAQ and accelerometer measures from the Walking Away study. Plots were completed for two accelerometer outputs: total MVPA time and MVPA time accumulated in bouts of at least 10 min. Regardless of the accelerometer MVPA definition, participants tended to substantially overestimate their MVPA time with self-report, although the discrepancy between measures was lower in SA participants. Specifically, the median difference between IPAQ and accelerometer total accumulated MVPA was 51 (10, 129) min/day for White participants and 21 (0, 63) min/day for SA participants; the corresponding figures when using accelerometer MVPA time in at least 10 min bouts were 67 (22, 148) and 35 (10, 78) min/day, respectively. All plots demonstrated strong proportional bias, with the difference between measures increasing in proportion to the average level of physical activity.

Figure 1.

Bland Altman plots showing the mean bias and limits of agreement when comparing self-reported MVPA with accelerometer derived total MVPA (graph A for White participants and C for South Asian participants) and MVPA accumulated in at least 10 min bouts (graph B for White participants and graph D for South Asian participants). MVPA, moderate-intensity to vigorous-intensity physical activity.

Sensitivity analysis

The difference in self-reported MVPA between White and SA ethnic groups was maintained if those reporting 0 min were removed from the analysis; the median (IQR) values were 77.0 (33, 154) and 51 (26, 120) min/day for White and SA participants, respectively (p<0.001).

Differences between ethnic groups in self-reported MVPA and walking activity were similar across studies (in all cases, SA participants reported levels of MVPA and walking activity 35–55% lower than White participants, (data not shown)). Levels of ambulatory activity for White and SA participants in Walking Away (accelerometer measure) were 6344 (4560, 8474) steps/day and 5847 (4300, 7756) steps/day, respectively (p=0.16 for difference). The same data for Let's Prevent (pedometer measure) were: 6100 (4337, 8113) steps/day and 6025 (4351, 8514) steps/day, respectively (p=0.28 for difference).

Discussion

This paper provides novel evidence showing that differences in self-reported levels of physical activity between White and SA groups are less pronounced with objective measurement. Specifically, while self-reported walking and MVPA levels were around 35–40% lower in SA individuals compared to the majority White population, no meaningful differences were observed in objectively measured ambulatory activity or MVPA in the combined cohort, although small ethnic differences were observed in objectively measured ambulatory activity for females, with SA females being less active, when results were stratified by sex. The lower levels of self-reported physical activity observed in SA participants showed better agreement with objective estimates compared to White participants who substantially over-estimated their activity levels.

Numerous studies relying on self-reported instruments have investigated differences in physical activity between White and SA populations in the UK and elsewhere.3–5 These studies have overwhelmingly reported substantial, clinically meaningful, ethnic-specific differences, consistent with the findings from this study.3 For example, a 2004 review of UK data identified 11 studies comparing SAs to White Europeans;3 all reported lower levels of physical activity within SA groups. More recent investigations based on large population-based samples have continued to support these findings.4 5

In contrast to self-report, there is a paucity of data investigating ethnic-specific differences in physical activity using objective measures in adults. However, although there is a lack of studies that have directly investigated the impact of self-reported and objectively measured physical activity in the same cohort over the same time period, emerging evidence from national survey data supports findings from this study that ethnic differences are less pronounced when objective measures are used. For example, accelerometer data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found no difference in levels of MVPA between Black and White participants;15 this was in contrast to earlier self-reported data, which revealed meaningful differences in physical activity levels between these ethnic groups.6 Similarly, large population based samples from the UK, including data from the Health Survey for England, have demonstrated that SA groups report 25–50% less activity than White Europeans.3–5 However, Health Survey for England data from 2008 found that ethnicity was not a significant predictor of objectively assessed fitness.20 Therefore, there is increasing evidence that differences in physical activity levels between ethnic groups may not be meaningful when objective measures are employed. The need for purposeful physical activity has been systematically engineered out of daily life in modern industrialised environments, therefore levels of physical activity within the general population in the UK and other industrialised countries are extremely low. For example, when measured objectively, less than 5% of the population undertake at least 30 min of MVPA, in bouts of at least 10 min, on at least 5 days of the week.20 21 Indeed, in the current study, participants accumulated an average of less than 30 min per week of MVPA in bouts of at least 10 min. Therefore, it is implausible that some ethnic groups could accumulate levels that are substantially lower than these already low values.

There are numerous reasons why spurious ethnic differences in levels of physical activity may be detected by self-report. Physical activity questionnaires have tended to be developed and validated in White populations, which is a limitation, as factors influencing recall bias are likely to vary across populations and ethnic groups. For example, inter-cultural differences in how concepts such as ‘moderate’ and ‘vigorous’ are interpreted, and norms around the social acceptability or desirability of undertaking purposeful physical activity have been reported as factors that may contribute to differences in how physical activity is self-reported.3 5 22 These factors have the potential to distort investigations into self-reported differences between groups. This study, therefore, helps reinforce the major limitations and high potential for erroneous conclusions when investigating differences in self-reported health behaviour across populations or ethnic groups.

This study also provides data for the validity of IPAQ in a primary care-based White and SA population. While correlation coefficients between IPAQ and objectively derived estimates of physical activity were low-to-moderate across both ethnic groups, they tended to be stronger for SA participants. Moreover, the degree of overestimating MVPA with self-report was around 50% lower in the SA group. Overall, our validity estimates are in agreement with other studies, which have reported that IPAQ and other physical activity questionnaires substantially overestimate levels of MVPA and provide weak to moderate correlations with objective criterion measures.23

This study has several strengths and limitations. Strengths include the large primary care-based sample and the fact that physical activity was measured using the most widely utilised self-report and objective instruments within lifestyle research. There are several limitations, which may all act to limit generalisability, including: the amount of missing data, particularly for SA participants in the Let's Prevent study; the relatively small size of the SA cohort; the high-risk nature of the included cohorts; and the fact that participants were being recruited into a clinical trial. Nonetheless, differences in self-reported physical activity between ethnic groups were consistent with previously published population level data in the UK.4 5 In addition, it is possible that the degree of reactivity to wearing an accelerometer for a week could have varied by ethnic group, potentially masking any true difference in physical activity levels. However, it is unlikely that this could account for the large discrepancy in ethnic-specific findings between self-reported and objectively measured activity levels.

In conclusion, this study found no, or small, differences between SA and White groups in objectively assessed physical activity despite self-reported estimates being 35–40% lower in the SA group. This finding casts doubt on the reality of the substantial ethnic-specific differences in levels of physical activity that have been reported with self-reported measures. The discrepancy in ethnic comparisons derived with objective and self-reported estimates of physical activity is a reminder of the limitations of trying to meaningfully compare physical activity behaviours across populations and ethnic groups with self-reported instruments, and suggests future studies should only attempt these types of comparisons when objective measures are available.

Acknowledgments

TY drafted the manuscript and analysed the data; DB assisted with analysis and interpretation of data; TY, CE, JH, KK and MJD contributed to the conception, design and acquisition of data; CE, JH, DB, KK and MJD provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; all the authors approved the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a National Institute for Health Research Programme grant, the National Institute for Health Research Leicester-Loughborough Diet, Lifestyle and Physical Activity Biomedical Research Unit and the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care—Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland (NIHR CLAHRC—LNR).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Nottingham NHS ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Barnett AH, Dixon AN, Bellary S et al. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk in the UK south Asian community. Diabetologia 2006;49:2234–46. 10.1007/s00125-006-0325-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams ED, Stamatakis E, Chandola T et al. Physical activity behaviour and coronary heart disease mortality among South Asian people in the UK: an observational longitudinal study. Heart 2011;97:655–9. 10.1136/hrt.2010.201012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischbacher CM, Hunt S, Alexander L. How physically active are South Asians in the United Kingdom? A literature review. J Public Health 2004;26:250–8. 10.1093/pubmed/fdh158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams ED, Stamatakis E, Chandola T et al. Assessment of physical activity levels in South Asians in the UK: findings from the Health Survey for England. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:517–21. 10.1136/jech.2009.102509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yates T, Davies MJ, Gray LJ et al. Levels of physical activity and relationship with markers of diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk in 5474 white European and South Asian adults screened for type 2 diabetes. Prev Med 2010;51:290–4. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crespo CJ, Smit E, Andersen RE et al. Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical inactivity during leisure time: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:46–53. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00105-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corder K, Brage S, Ekelund U. Accelerometers and pedometers: methodology and clinical application. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2007;10:597–603. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328285d883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yates T, Davies MJ, Henson J et al. Walking away from type diabetes: trial protocol of a cluster randomized controlled trial evaluating a structured education programme in those at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes. BMC Fam Pract 2012; 13:46 10.1186/1471-2296-13-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray LJ, Khunti K, Williams S et al. Let's prevent diabetes: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial of an educational intervention in a multi-ethnic UK population with screen detected impaired glucose regulation. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2012;11:56 10.1186/1475-2840-11-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray LJ, Khunti K, Edwardson C et al. Implementation of the automated Leicester Practice Risk Score in two diabetes prevention trials provides a high yield of people with abnormal glucose tolerance. Diabetologia 2012;55:3238–44. 10.1007/s00125-012-2725-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray LJ, Davies MJ, Hiles S et al. Detection of impaired glucose regulation and/or type 2 diabetes mellitus, using primary care electronic data, in a multiethnic UK community setting. Diabetologia 2012;55:959–66. 10.1007/s00125-011-2432-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The English Indices of Deprivation 2007: Summary. http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/communities/pdf/576659.pdf (accessed 26 May 2010).

- 13.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1381–95. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998;30:777–81. 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW et al. Physical Activity in the United States Measured by Accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008;40:181–8. 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crouter SE, Schneider PL, Bassett DR Jr. Spring-levered versus piezo-electric pedometer accuracy in overweight and obese adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37:1673–9. 10.1249/01.mss.0000181677.36658.a8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider PL, Crouter SE, Bassett DR. Pedometer measures of free-living physical activity: comparison of 13 models. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004;36:331–5. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000113486.60548.E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tudor-Locke C, Burkett L, Reis JP et al. How many days of pedometer monitoring predict weekly physical activity in adults? Prev Med 2005;40:293–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abel MG, Peritore N, Shapiro R et al. A comprehensive evaluation of motion sensor step-counting error. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2011;36:166–70. 10.1139/H10-095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NHS Information Centre. Health survey for England—2008: physical activity and fitness 2009. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/statistics-and-data-collections/health-and-lifestyles-related-surveys/health-survey-for-england/health-survey-for-england--2008-physical-activity-and-fitness

- 21.Tudor-Locke C, Brashear MM, Johnson WD et al. Accelerometer profiles of physical activity and inactivity in normal weight, overweight, and obese US men and women. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010;7:60 10.1186/1479-5868-7-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolin KY, Fagin C, Ufere N et al. Physical activity in UK Blacks: a systematic review and critical examination of self-report instruments. Int J Behav Nutr Phys 2010;7:73 10.1186/1479-5868-7-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee PH, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH et al. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:115 10.1186/1479-5868-8-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]