Abstract

Objectives

The present study is aimed at describing the seroprevalence and exploring potential risk factor(s) for hepatitis E virus (HEV) in participants who voluntarily underwent anti-HIV antibody testing.

Study design

Seroprevalence study.

Setting

The HIV prevention unit at the National Institute for Infectious Diseases Lazzaro Spallanzani, serving as a referral centre for HIV infection in Lazio, an Italian Region with about 5.6 million inhabitants.

Participants

Participants are a random sample of all subjects who receive counselling and undergo serological tests for anti-HIV antibody (Ab) between 2002 and 2011.

Risk factors and outcome

A set of 16 epidemiological variables (risk factors) were assessed for association with positivity to anti-HEV IgG (outcome).

Results

Between 2002 and 2011, 27 351 serum specimens and related epidemiological information were collected; of these 1116 were randomly selected and analysed. The overall anti-HEV IgG prevalence was 5.38% (60 out of 1116) with evidence of potential heterogeneity between years of sampling (p=0.055). Multivariate analysis provided evidence that anti-HEV IgG prevalence increases by 4% per year of participants’ age (95% CI 1% to 7%, p=0.002). In addition, men who have sex with men and participants who were born outside Italy have an OR for past HEV infection that is about two times higher than in those who were not (p=0.040 and p=0.027, respectively). Analysis of temporal trend showed that variation of anti-HEV IgG can be well explained by a cubic logistic regression model, which describes the variation of prevalence over time as a fluctuation within a 3-year period (p=0.032).

Conclusions

This study provides new evidence that besides the orofecal and zoonotic routes, intimate contacts between males may be a significant mode of HEV transmission.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Recent studies have pointed out that, in Europe and North America, infections with hepatitis E virus (HEV) might be more frequent than expected.

Here, we carried out a seroprevalence study to describe HEV epidemiology and to assess potential risk factors associated with past infections (ie, positivity to anti-HEV IgG).

People born outside Italy and men who have sex with men have an increased risk of testing positive to anti-HEV IgG.

Despite its limitation (the study population mainly comprises healthy young adults whose HEV genotypes could not be established on a serological basis), this study provides new insights about the spreading of HEV in industrialised countries.

Background

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection is one of the most common causes of enterically transmitted hepatitis in countries with low and intermediate healthcare standards.1 In industrialised countries, autochthonous cases of acute infection with HEV are often reported as sporadic cases occurring in clusters associated with occupational exposure (mainly pig handlers)2 3 and/or consumption of contaminated food.4 5 Nevertheless, recent studies have pointed out that, in Europe and North America, infections with HEV might be more frequent than expected,6 suggesting that a direct human-to-human contact may play a significant role in the transmission of the virus in these settings. In particular, it has been proposed that HEV may share transmissions pathways with sexually transmitted pathogens such as HIV.7 8 This latter observation has a topical clinical interest since it has been recently proved that HEV may produce severe chronic infections in immunocompromised participants, including those infected with HIV.9 10

The aim of this study is to explore potential risk factors (other than food and occupational exposure during animal handling) associated with evidence of past HEV infection in a large sample of participants living in Rome (Italy) and its suburbs, who voluntarily underwent anti-HIV antibody (anti-HIV Ab) testing between 2002 and 2011. The study is reported according to the STROBE statement.11

Material and methods

Study design

The study is based on a 10-year seroprevalence study carried out at the unit for HIV prevention of the Italian National Institute for Infectious Diseases Lazzaro Spallanzani (INMI-Spallanzani) between 2002 and 2011.

Setting

INMI-Spallanzani is a 200-bed hospital and research centre which serves as a referral centre for HIV infection diagnosis and therapy for Lazio, an Italian Region with about 5.6 million inhabitants. About 47% of Lazio inhabitants live in Rome, the only large city. All other people live in the 347 municipalities, mainly towns (median habitants 2674 IQR 1120–7997). The unit for HIV prevention at INMI-Spallanzani is an outpatient clinic where people may receive counselling for HIV infection, have access to diagnostics and receive pre-exposure/postexposure prophylaxis. The unit prescribes about 2500 HIV tests per year to patients who come from all over the region.

Participants

Participants are a random sample of all patients who receive counselling and undergo serological tests for anti-HIV Ab (for any reason) at INMI-Spallanzani between 2002 and 2011.

Variables

A set of 16 epidemiological variables (risk factors, see table 1, left column) were assessed for potential association with positivity to anti-HEV IgG (outcome) which was used as a marker for past infection with HEV. All risk factors were analysed as binary variables apart form patient's age and the year of sampling which were analysed as continuous variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive and inferential analysis for risk factors of HEV infections

| Descriptive analysis |

ULR model |

Final MLR model† |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEV IgG |

||||||||||||

| Risk factors* | All | Per cent | Positive | Negative | OR | 95% | CI | p Value | OR | 95% | CI | p Value |

| Age‡ | – | – | – | – | 1.03§ | 1.01 | 1.06 | 0.008 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.07 | 0.002 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 414 | 37.10 | 18 | 396 | Base | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Male | 702 | 62.90 | 42 | 660 | 1.40¶ | 0.79 | 2.47 | 0.244 | – | – | – | – |

| MSM | ||||||||||||

| No | 879 | 78.76 | 42 | 837 | Base | – | base | –- | ||||

| Yes | 237 | 21.24 | 18 | 219 | 1.64 | 0.92 | 2.90 | 0.091 | 1.90 | 1.03 | 3.50 | 0.040 |

| HCW | ||||||||||||

| No | 882 | 79.03 | 44 | 838 | Base | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Yes | 234 | 20.97 | 16 | 218 | 1.40¶ | 0.77 | 2.52 | 0.267 | – | – | – | – |

| Sex worker | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 19 | 1.70 | 1 | 18 | Base | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| No | 1097 | 98.30 | 59 | 1038 | 1.02 | 0.13 | 7.80 | 0.982 | – | – | – | – |

| HIV Ab | ||||||||||||

| Pos. | 55 | 4.93 | 3 | 52 | Base | – | base | |||||

| Neg. | 1061 | 95.07 | 57 | 1004 | 0.98§ | 0.30 | 3.25 | 0.979 | 1.23 | 0.35 | 4.29 | 0.742 |

| IDU | ||||||||||||

| No | 1066 | 95.52 | 56 | 1010 | Base | – | base | – | ||||

| Yes | 50 | 4.48 | 4 | 46 | 1.57 | 0.55 | 4.51 | 0.404 | 2.18 | 0.72 | 6.56 | 0.168 |

| Born in Italy | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1006 | 90.14 | 49 | 957 | Base | – | base | – | ||||

| No** | 110 | 9.86 | 11 | 99 | 2.17 | 1.09 | 4.31 | 0.027 | 2.25 | 1.10 | 4.61 | 0.027 |

| Living in Rome | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 986 | 88.35 | 49 | 937 | Base | – | Base | – | ||||

| No | 130 | 11.65 | 11 | 119 | 1.77 | 0.89 | 3.49 | 0.101 | 1.77 | 0.87 | 3.60 | 0.115 |

| Preconception care | ||||||||||||

| No | 1067 | 95.61 | 57 | 1010 | Base | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Yes | 49 | 4.39 | 3 | 46 | 1.16 | 0.35 | 3.83 | 0.813 | – | – | – | – |

| HIV-positive partner | ||||||||||||

| No | 919 | 82.35 | 47 | 872 | Base | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Yes | 197 | 17.65 | 13 | 184 | 1.31 | 0.70 | 2.47 | 0.403 | – | – | – | – |

| Legal†† | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 145 | 12.99 | 6 | 139 | Base | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| No | 971 | 87.01 | 54 | 917 | 1.36 | 0.58 | 3.23 | 0.480 | – | – | – | – |

| New partnership | ||||||||||||

| No | 1012 | 90.68 | 52 | 960 | Base | – | Base | – | ||||

| Yes | 104 | 9.32 | 8 | 96 | 1.54 | 0.71 | 3.33 | 0.275 | 1.83 | 0.81 | 4.12 | 0.143 |

| Condom rupture | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 50 | 4.48 | 2 | 48 | Base | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| No | 1066 | 95.52 | 58 | 1008 | 1.38 | 0.33 | 5.82 | 0.660 | – | – | – | – |

| Occasional sex | ||||||||||||

| No | 869 | 77.87 | 46 | 823 | Base | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Yes | 247 | 22.13 | 14 | 233 | 1.08 | 0.58 | 1.99 | 0.818 | – | – | – | – |

| Year of testing‡‡ | – | – | – | – | –§ | – | – | 0.087 | – | – | – | 0.062 |

| All | 1116 | 100.00 | 60 | 1056 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

The final MLR model was set using three a priori confounders and five additional variables selected by a stepwise approach. The variable with an OR≥ 1.40 in the ULR analysis and intermediate MLR models (not shown) were included in the final model whose fitness was eventually assessed versus the full MLR model (not shown) which included all the variables.

†Likelihood ratio test to assess final model nested in full model p=0.988.

‡Age is included as a continuous variable (mean 34.60; SD 10.15).

§A priori confounders.

¶OR<1.40 in the intermediate models (not shown).

**This is: 34 in eastern Europe, 32 in Latin America, 20 in Africa, 16 in western Europe, 4 in North America, 3 in Asia and 1 in Australia.

††Anti-HIV test required by law (eg, adoption).

‡‡Year of testing for HIV is included as a categorical 10-level variable.

Ab, antibody; HCW, healthcare workers (occupational exposure); IDU, injective drug user (ever in life); MLR, multivariate logistic regression; MSM, men who have sex with men; ULR, univariate logistic regression.

Data source and virology assessment

Participants’ epidemiological information was prospectively collected by the doctors on a standard form on the day each patient underwent the test for anti-HIV Ab. Serum samples were prospectively collected according to the Lazio directive which disposes of mandatory sera collection for each patient who undergoes HIV testing. Sera were stored at the INMI-Spallanzani biorepository and preserved at −20°C.

Anti-HEV IgG assays were carried out on specimens preserved in the bio-repository by means of a commercially available ELISA kit (DIA.PRO, Milan, Italy) and according to the manufacturer's instructions. In our experience, clinical sensitivity is ≥97.6%, while specificity is >96.7%.

Study size

The study was powered in order to discern risk factors which can increase the prevalence of anti-HEV IgG prevalence from 5% (the estimate for the Italian general population) to 7% (ie, an OR of 1.4), with a power of 0.80 and an α error of 0.05. The null hypothesis for all inferential analyses was that the HEV IgG prevalence among subjects with a specific risk factor is equal to the prevalence for the general population.

Statistical methods

ORs and 95% CIs were used as measures of association. The association between HEV IgG positivity and potential risk factors was assessed in univariate and multivariate logistic regression models.

The best set of variables for the final multivariate model was chosen according to simplicity and fitness criteria using a manual stepwise approach. Variables with an OR ≥1.40 at univariate analysis were included in subsequent multivariate models (intermediate model) whose fitness was assessed by a likelihood ratio test (LRT). Subsequent intermediate models were set up by removing variables with OR <1.40. A simpler model was assumed whenever the LRT p value was >0.10. Age, results of anti-HIV test and year of sampling (as a 10-level categorical variable) were considered as a priori confounders and included in all the models.

Potential secular trends of anti-HEV IgG prevalence in our population were studied in additional multivariate logistic models to assess linear and non-linear associations between anti-HEV IgG and year of sampling (as a continuous variable). Model fitness was assessed using the LRT test.

According to standard terminology, the association between outcome and risk factors was referred to as: ‘no evidence’ when p value was ≥0.100, ‘weak evidence’ for p value between 0.099 and 0.050 or ‘strong evidence’ for p value<0.050.

The STATA V.12.0 statistical package was used for all analyses.

Results

Participant and sample description

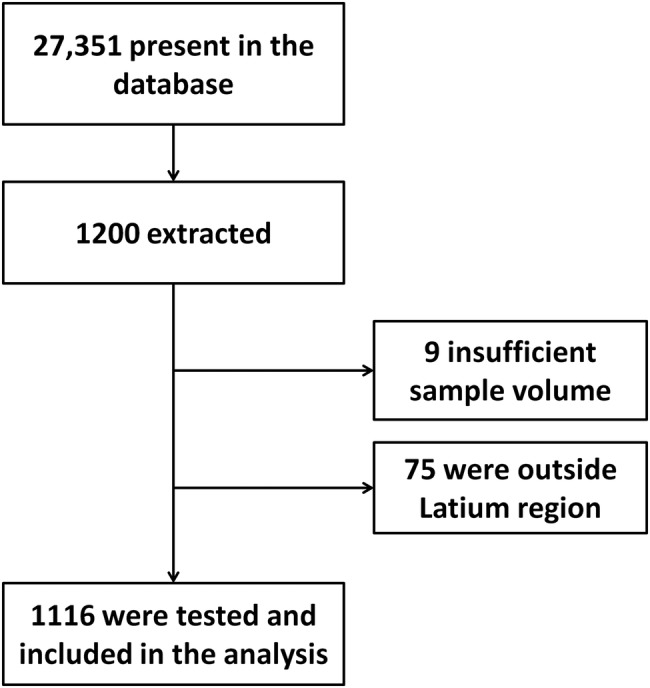

Between 2002 and 2011, 27 351 serum specimens and related epidemiological information were collected; of these, 1200 were randomly selected and 1116 were analysed (figure 1 and table 1). Nine samples were excluded because of insufficient volume for analysis and 75 because they were from participants living outside Lazio (figure 1). The main characteristics of the sample are reported in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for serum samples selection.

Main results

The overall anti-HEV IgG prevalence was 5.38% (60 of 1116) with evidence of potential heterogeneity between years of sampling (p=0.055, see tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Distribution results of anti-HEV IgG according to year of sampling

| Years of sampling | HEV IgG |

All tested | Odds of prevalence (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (%) | Negative | |||

| 2002 | 5 (4.50) | 106 | 111 | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.12) |

| 2003 | 6 (5.41) | 105 | 111 | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.13) |

| 2004 | 3 (2.56) | 114 | 117 | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.08) |

| 2005 | 5 (4.35) | 110 | 115 | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.11) |

| 2006 | 4 (3.74) | 103 | 107 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.11) |

| 2007 | 3 (2.56) | 114 | 117 | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.08) |

| 2008 | 13 (11.71) | 98 | 111 | 0.13 (0.07 to 0.24) |

| 2009 | 8 (7.48) | 99 | 107 | 0.08 (0.04 to 0.17) |

| 2010 | 9 (8.11) | 102 | 111 | 0.09 (0.04 to 0.17) |

| 2011 | 4 (3.67) | 105 | 109 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.10) |

| Total | 60 (5.38) | 1056 | 1116 | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.07) |

The odds of prevalence are calculated as the frequency of positive tests divided by the frequency of negative ones. 95% CI is calculated with the square root of the variance of the score statistic. The χ2 test for homogeneity provides evidence that the prevalence may significantly change in the different year of sampling (p for no difference across the period=0.057).

Univariate analyses (table 1) provided weak to strong evidence that age (p=0.008), men who have sex with men (MSM; p=0.091) and being born outside Italy (p=0.027) were all risk factors significantly associated with positivity to anti-HEV IgG.

Multivariate analysis (table 1) included eight independent variables (ie, three as a priori confounders and five selected through the stepwise process). This analysis confirmed and strengthened the results of the univariate models. In particular, this model estimated that: anti-HEV IgG prevalence increases by 4% per year of participants’ age (95% CI 1% to 7%, p=0.002) and that MSM and participants who were born outside Italy have an OR for past infection with HEV that is about two times higher than for those who were not (ie, 1.90 95% CI 1.03 to 3.50, p=0.040 and 2.25 95% CI 1.10 to 4.61, p=0.027, respectively). In addition, the analysis provided weak evidence that prevalence of anti-HEV IgG varied throughout the period (p=0.062).

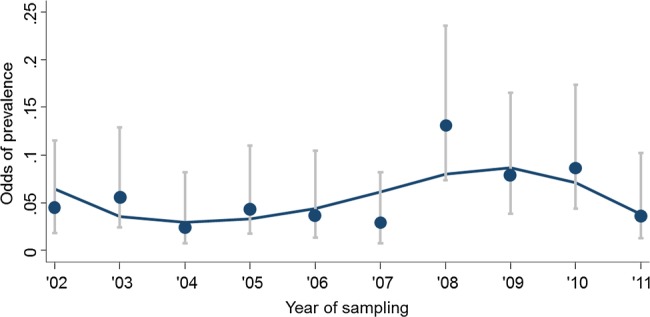

Other analyses

Since all the analyses suggested a variation of HEV IgG prevalence over time, we carried out an additional analysis to improve the inferential power of the model for describing at best this observation (figure 2). For this purpose, additional multivariate logistic models, including the year of sampling as a continuous variable, were implemented using the same set of variables included in the final multivariate model. In this way, we assessed linear and non-linear (ie, quadratic and cubic) associations between the year of sampling and anti-HEV IgG (outcome). The analysis reported in figure 2 showed that the change of anti-HEV IgG prevalence throughout the period could be, at best, described by a multivariate logistic model which included year of sampling as a cubic term, modelling the variations of prevalence as a fluctuation with a period of about 3 years (p=0.032).

Figure 2.

Variation of anti hepatitis E virus (HEV) IgG prevalence according to the year of sampling. The line indicates the odds of prevalence of anti-HEV positivity predicted according to the polynomial logistic regression model, which included years of sampling as a third power. Dots within horizontal bars represent observed odds of prevalence with respective 95% CI.

Discussion

This study was carried out among a population that mainly comprised young adults who lived in the city of Rome and its suburbs and who underwent an anti-HIV Ab test either for sexual or occupational exposure. The results indicate that, besides age, being MSM and being born outside Italy are both risk factors independently associated with past infection with HEV. In addition, we observed that in the study population the prevalence of anti-HEV IgG was not constant between 2002 and 2011.

The association with age, although observed in a population quite homogeneous for age, is expected on the basis of the presumed long persistence of IgG after HEV acute infection, and is consistent with previous evidence from studies carried out in different settings.12 In fact, age was considered as an a priori confounder and included in all inferential models.

The increased risk for HEV infection among MSM is noteworthy, though not unexpected.13 14 The association between homosexual intercourses among males and the increased risk of HEV has been recently suggested by Payne et al13 who carried out a study in the UK among a population of young adults at risk of sexually transmitted infections and obtained results very similar to ours. The mechanisms for HEV transmission among MSM are most probably associated with oro–anal sexual practices, which were also implicated in a recent outbreak of HAV in Rome among HIV-positive MSM.15 In contrast, we observed that anti-HEV IgG positivity was not independently associated with HIV infection, which suggests that HEV and HIV do not share similar pathways of transmission, though a special population, such as MSM, may be at increased risk of both infections due to concurrent behaviours (eg, penetrative anal intercourse for HIV and oro–anal sexual practice for HEV).

Owing to the still significant prevalence of HIV infection among MSM (12.4% in our study, data not shown) and to the possibility that HIV-positive participants may develop severe chronic hepatitis E,16 17 HEV could become a clinical issue for MSM in Europe in the near future, if the increasing trend of infection is confirmed.18–21

Participants who were born outside Italy were at higher risk for HEV infection than those who were born in Italy. Our data do not permit us to establish an unequivocal explanation for this finding; however, consumption of undercooked pork meat and/or poor health condition in several of the countries of origin might have contributed to the increased risk in this subgroup. Moreover, our findings are consistent with other surveillance studies carried out in Italy. In particular, a recent surveillance that aimed to assess the spread of HEV in Apulia (Southern Italy) indicated that the prevalence of anti-HEV IgG was much higher among immigrants (19.7%) than among Italian people (3.9%). It is noteworthy that this study also shows no evidence for an increased prevalence of anti-HEV IgG among participants with HIV infection.22

The time pattern observed here for the fluctuation of anti-HEV IgG prevalence across the period is not entirely consistent with the expected lifelong antibody response against HEV. Nonetheless, existing data on the persistence of anti-HEV IgG after the resolution of the acute infection are not univocal. In fact, while some authors have provided evidence for a long persistence of IgG,12 23 24 other (most recent) studies suggest a potential decline of humoral response over time, which can partially justify our results.25 26 However, it cannot be excluded that the observed fluctuation of prevalence may be an artefact due to the study design and/or the effect of uneven distribution across the period of unknown/uncontrolled predisposing conditions which can have introduced a (secular) selection bias. A large cohort study or a specifically designed case–control study is necessary for an in-depth investigation of the temporal trends of HEV seroprevalence in our geographical area.

The participants in this study are mainly young adults in apparently good health and at self-perceived high risk of HIV infection; therefore, attention must be paid while generalising results. In particular: (1) the 5.38% overall prevalence observed in this study may underestimate the actual prevalence of HEV infection as the study participants are younger than the general population of the area (in fact, a strong direct log-linear association between age and prevalence of anti-HEV IgG was found); (2) results cannot be directly generalised to special population groups such as immunocompromised hosts, patients with haemodialysis and/or persons with chronic viral hepatitis; (3) MSMs are the only group represented in the study which is likely to have increased exposure to oro–anal intercourse; therefore, we cannot exclude that behaviours other than oro–anal practices can be involved in the increased risk of HEV infection in this group.

Available data suggest that in Europe anti-HEV prevalence varies widely, ranging between 0.26% (Greece)27 and 52.50% (France).28 It has been suggested that these differences could be due to the variable performance of the different tests used.29 Thus, a direct comparison between the anti-HEV IgG prevalence reported in this study and that reported in other studies, based on different tests, might be inappropriate.30 Nevertheless, we feel that this issue is unlikely to bias the results of our risk analysis as: (1) the commercial kit used in this study has been recently reported to have good performance in comparison to other commonly used tests;31 (2) the occurrence of differential misclassification affecting the internal validity of the study (ie, information bias) is unlikely as specimens were all tested in the same laboratory with the same test and identical procedures.

Finally, the study did not assess several risk factors already known to be associated with the exposure to HEV such as food habits and occupational exposure among animal handlers (but this was outside our intents), and given that we assessed only humoral response (anti-HEV IgG), we could not provide any information about the spread of HEV genotypes in the area.

In conclusion, despite its limitation, this study provides new insights about modes of transmission of hepatitis E in industrialised countries. Here, we propose that in industrialised countries, beside the already known orofaecal route through contaminated food/water or zoonotic exposure, HEV can be directly transmitted between humans through oro–anal intercourse similar to other enterically transmitted pathogens such as HAV15 and salmonella.32

Footnotes

Contributors: SL, MRC and GI designed the research. AN and VP performed the research. ARG, CP and DL contributed new reagents/analytic tools. SL analysed the data. SL, MRC and GI wrote the paper.

Funding: The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under Grant Agreement no 278433-PREDEMICS, and from the Italian Ministry of Health, Ricerca Corrente.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The design of this study has been approved by INMI Lazzaro Spallanzani and PREDEMICS ethical boards.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Kmush B, Wierzba T, Krain L et al. . Epidemiology of hepatitis E in low- and middle-income countries of Asia and Africa. Semin Liver Dis 2013;33:15–29. 10.1055/s-0033-1338111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berto A, Backer JA, Mesquita JR et al. . Prevalence and transmission of hepatitis E virus in domestic swine populations in different European countries. BMC Res Notes 2012;5:190 10.1186/1756-0500-5-190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaussade H, Rigaud E, Allix A et al. . Hepatitis E virus seroprevalence and risk factors for individuals in working contact with animals. J Clin Virol. 2013;58:504–8. 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Bartolo I, Diez-Valcarce M, Vasickova P et al. . Hepatitis E virus in pork production chain in Czech Republic, Italy, and Spain, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:1282–9. 10.3201/eid1808.111783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maunula L, Kaupke A, Vasickova P et al. . Tracing enteric viruses in the European berry fruit supply chain. Int J Food Microbiol 2013;167:177–85. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arends JE, Ghisetti V, Irving W et al. . Hepatitis E: an emerging infection in high income countries. J Clin Virol 2014;59:81–8. 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mateos-Lindemann ML, Diez-Aguilar M, Galdamez AL et al. . Patients infected with HIV are at high-risk for hepatitis E virus infection in Spain. J Med Virol 2014;86:71–4. 10.1002/jmv.23804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouamra Y, Benali S, Tissot-Dupont H et al. . Hepatitis B and E co-primary infections in an HIV-1-infected patient. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:1052–6. 10.1128/JCM.02630-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalton HR, Bendall RP, Keane FE et al. . Persistent carriage of hepatitis E virus in patients with HIV infection. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1025–7. 10.1056/NEJMc0903778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jagjit Singh GK, Ijaz S, Rockwood N et al. . Chronic hepatitis E as a cause for cryptogenic cirrhosis in HIV. J Infect 2013;66:103–6. 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Little J, Higgins JP, Ioannidis JP et al. . STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association Studies. STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association Studies (STREGA): an extension of the STROBE statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e22 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khuroo MS, Kamili S, Dar MY et al. . Hepatitis E and long-term antibody status. Lancet 1993;341:1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payne BA, Medhi M, Ijaz S et al. . Hepatitis E virus seroprevalence among men who have sex with men, United Kingdom. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:333–5. 10.3201/eid1902.121174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Welzen BJ, Verduyn Lunel FM, Meindertsma F et al. . Hepatitis E virus as a causative agent of unexplained liver enzyme elevations in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;60:e65–67. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318251b01f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bordi L, Rozera G, Scognamiglio P et al. . GEAS Group. Monophyletic outbreak of hepatitis A involving HIV-infected men who have sex with men, Rome, Italy 2008–2009. J Clin Virol 2012;54:26–9. 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kenfak-Foguena A, Schöni-Affolter F, Bürgisser P et al. . Data Center of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, Lausanne, Switzerland. Hepatitis E Virus seroprevalence and chronic infections in patients with HIV, Switzerland. Emerg Infect Dis 2011;17:1074–8. 10.3201/eid/1706.101067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colson P, Dhiver C, Poizot-Martin I et al. . Acute and chronic hepatitis E in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Viral Hepat 2011;18:227–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01311.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colson P, Romanet P, Moal V et al. . Autochthonous infections with hepatitis E virus genotype 4, France. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:1361–4. 10.3201/eid1808.111827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slot E, Hogema BM, Riezebos-Brilman A et al. . Silent hepatitis E virus infection in Dutch blood donors, 2011 to 2012. Euro Surveill 2013;18:20550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalupa P, Vasickova P, Pavlik I et al. . Endemic hepatitis E in the Czech Republic. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:509–16. 10.1093/cid/cit782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramalingam S, Smith D, Wellington L et al. . Autochthonous hepatitis E in Scotland. J Clin Virol. 2013;58:619–23. 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scotto G, Martinelli D, Centra M et al. . Epidemiological and clinical features of HEV infection: a survey in the district of Foggia (Apulia, Southern Italy). Epidemiol Infect 2014;142:287–94. 10.1017/S0950268813001167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dawson GJ, Chau KH, Cabal CM et al. . Solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for hepatitis E virus IgG and IgM antibodies utilizing recombinant antigens and synthetic peptides. J Virol Methods 1992;38:175–86. 10.1016/0166-0934(92)90180-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryan JP, Tsarev SA, Iqbal M et al. . Epidemic hepatitis E in Pakistan: patterns of serologic response and evidence that antibody to hepatitis E virus protects against disease. J Infect Dis 1994;170:517–21. 10.1093/infdis/170.3.517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitsui T, Tsukamoto Y, Suzuki S et al. . Serological and molecular studies on subclinical hepatitis E virus infection using periodic serum samples obtained from healthy individuals. J Med Virol 2005;76:526–33. 10.1002/jmv.20393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myint KS, Endy TP, Shrestha MP et al. . Hepatitis E antibody kinetics in Nepalese patients. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2006;100:938–41. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stefanidis I, Zervou EK, Rizos C et al. . Hepatitis E virus antibodies in hemodialysis patients: an epidemiological survey in central Greece. Int J Artif Organs 2004;27:842–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansuy JM, Bendall R, Legrand-Abravanel F et al. . Hepatitis E virus antibodies in blood donors, France. Emerg Infect Dis 2011;17:2309–12. 10.3201/eid1712.110371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossi-Tamisier M, Moal V, Gerolami R et al. . Discrepancy between anti-hepatitis E virus immunoglobulin G prevalence assessed by two assays in kidney and liver transplant recipients. J Clin Virol 2013;56:62–4. 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khudyakov Y, Kamili S. Serological diagnostics of hepatitis E virus infection. Virus Res 2011;161:84–92. 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pas SD, Streefkerk RH, Pronk M et al. . Diagnostic performance of selected commercial HEV IgM and IgG ELISAs for immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. J Clin Virol 2013;58:629–34. 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reller ME, Olsen SJ, Kressel AB et al. . Sexual transmission of typhoid fever: a multistate outbreak among men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:141–4. 10.1086/375590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]