Abstract

Objectives

To assess the effect of Michigan's smoke-free air (SFA) law on the air quality inside selected restaurants and casinos. The hypothesis of the study: if the SFA law is effectively implemented in restaurants and casinos, there will be a significant reduction in the particulate matter PM2.5 measured in the same establishments after the law is implemented.

Setting

Prelaw and postlaw design study.

Participants

78 restaurants in 14 Michigan cities from six major regions of the state, and three Detroit casinos.

Methods

We monitored the real-time PM2.5 in 78 restaurants and three Detroit casinos before the SFA law, and again monitored the same restaurants and casinos after implementation of the law, which was enacted on 1 May 2010.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Concentration measurements of secondhand smoke (SHS) fine particles (PM2.5) were compared in each restaurant in the prelaw period to measurements of PM2.5 in the same restaurants during the postlaw period. A second comparison was made for PM2.5 levels in three Detroit casinos prelaw and postlaw; these casinos were exempted from the SFA law.

Results

Prelaw data indicated that 85% of the restaurants had poor to hazardous air quality, with the average venue having ‘unhealthy’ air according to Michigan's Air Quality Index for PM2.5. Postlaw, air quality in 93% of the restaurants improved to ‘good’. The differences were statistically significant (p<0.0001). By comparison, the three casinos measured had ‘unhealthy’ air both before and after the law.

Conclusions

The significant air quality improvement in the Michigan restaurants after implementation of the SFA law indicates that the law was very effective in reducing exposure to SHS. Since the Detroit casinos were exempted from the law, the air quality was unchanged, and remained unhealthy in both prelaw and postlaw periods.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, Smoking and tobacco

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study with 78 restaurant venues, the largest, single US study of its kind, adds increasing evidence to the literature supporting the risk reduction from exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) after a smoke-free air (SFA) law was passed, demonstrating that the SFA law was successful in achieving the objective of significant reduction in the particulate matter PM2.5 measured in the same establishments before and after the law.

The three casinos exempted from the SFA law in Detroit city continue to pose a health risk to employees and patrons, as demonstrated by the high levels of fine particle air pollution that were present before and after the SFA law went into effect.

The annual particulate burden from SHS for full-time employees of the three casinos was six times higher than the US Environmental Protection Agency's annual average PM2.5 standard, both before and after the SFA law was implemented, and was at the 80th percentile of all 66 US casinos previously studied.

A limitation of this study is that a convenience sample was used to select the restaurants included in the study, introducing the potential for less objective comparisons than might occur in a random sample.

Another limitation is that SHS is not the only source of PM2.5 particles.

Introduction

Secondhand smoke (SHS) contains more than 7000 chemicals. Hundreds are toxic, about 70 are known to cause cancer, and many cause numerous health problems in infants and children, including severe asthma attacks, respiratory infections and ear infections. In adults, exposure to SHS causes heart disease and lung cancer.1 There is no risk-free level of exposure to SHS. Even brief exposure has immediate harmful effects on the cardiovascular system, which can increase the risk of heart attack.1–3

The hazardous health effects of exposure to SHS are well documented and established in various independent research studies and numerous international reports.1 4 Scientific evidence has unequivocally established that SHS causes premature death and disease. Most of the disease burden from exposure to SHS results from cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, nasal sinus and breast cancer, as well as respiratory disease and developmental effects in children.1 4 Evidence also supports the association of exposure to SHS with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The health effects of exposure to SHS are detailed in the US Surgeon General's report.1 Exposure to SHS causes an estimated 46 000 premature deaths from heart disease and 3400 deaths from lung cancer each year among non-smokers in the USA.3–5

Research documents population-level health benefits associated with implementation of comprehensive smoke-free laws covering all public places and worksites, including bars and restaurants. These laws reduced exposure to SHS, improved the health of hospitality workers, improved indoor air quality, reduced incidence of acute myocardial infarctions and reduced incidence of asthma exacerbations.1 6 7 However, exemptions to smoke-free laws afforded to casinos leave workers at elevated risk of heart disease and other diseases.8

The State of Michigan enacted the Dr Ron Davis Smoke Free Air (SFA) Law in 2009 (Public Act 188), and the law went into effect on 1 May 2010. The law prohibits smoking in all public places and worksites, including bars and restaurants, but has exempted three Detroit casinos. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that states perform studies to assess indoor air quality inside hospitality venues before and after the implementation of SFA laws.9

The purpose of this study is to determine the effect of Michigan's SFA Law on the level of fine particulate matter ≤2.5 µ in diameter (PM2.5) in 78 restaurants in 14 cities state-wide, and in three Detroit casinos, by comparing PM2.5 prior to implementation of the SFA law with PM2.5 post-implementation of the SFA law. Prior to implementation of the law, all the 78 restaurants and three casinos allowed smoking indoors. After implementation of the law, smoking was prohibited in the 78 restaurants, but still allowed in the three casinos.

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) measured in numerous hospitality venues has been found to contain a substantial fraction of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.8 10 11

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) stated that scientific studies have found an association between exposure to fine particulate matter and health problems, including: aggravated asthma, chronic bronchitis, reduced lung function, heart attack and premature death in people with heart or lung disease.12

This study will answer questions concerning: (1) the concentration of the PM2.5 in 78 restaurants before and after the law, (2) whether the PM2.5 declines significantly in these restaurants after the law; and (3) if there is any significant difference in the level of PM2.5 in the three exempted Detroit casinos before and after the law.

Methods

Study design

The Tobacco Control Program of the Michigan Department of Community Health, with assistance from local health departments and their tobacco reduction coalitions, recruited and trained field volunteers to measure the air quality in a sample of restaurants from 2005 through 2008, prior to the enactment of the Michigan SFA law. These restaurants were monitored for PM2.5 before and then again after implementation of the law for PM2.5. The volunteers were instructed to monitor the restaurants during high-volume customer visits, such as weekend evenings. The same instructions applied to the three Detroit casinos.

Study sample and selection

A sample of 78 restaurants was selected because they allowed smoking and had indoor seating. They were located in 14 Michigan cities from six distinct geographic regions of the state. The following cities participated in the study: Ann Arbor, Detroit, Flint, Grand Rapids, Kalamazoo, Lansing, East Lansing, Marquette, Midland, Novi, Saginaw, Sault Ste Marie, Traverse City and West Branch. Three casinos in the city of Detroit were selected because they are the only casinos in Michigan that were exempted by the SFA law. After the implementation of the law, the same restaurants were monitored again except one, in the city of Novi, because it was closed for remodelling. The three Detroit casinos were also monitored again.

Measurement

The concentration of respirable suspended particles PM2.5 was measured using two SidePak Personal Aerosol Monitors, Model AM510 (TSI, Minnesota, USA), which is a battery-powered lightweight photometer. The built-in sampling pump has a size-selective inlet for area measurements with a PM2.5 impactor. The SidePak AM 510 flow rates were set to 1.7 L/min and for 1 min logging intervals. The SidePak was zero calibrated prior to each use by attaching a HEPA filter according to the manufacturer's specifications.

The volunteer field personnel concealed the monitors in purses, shoulder bags or backpacks. They entered the venue as paying customers, were seated and placed orders for food or beverages. They monitored air quality for at least 30 min in each venue. The total number of persons and the number of active smokers were recorded three times during the 30 min visit. The field volunteers also measured the ceiling heights and floor space of the venue using a laser ruler. They recorded times of arrival and departure for each of the venues in a field diary. These data permit calculation of smoker prevalence and smoker density, and the interpreting of results.

Data analysis

The SidePak calibration factors were set to 1 during the measurements, based on factory calibration. However, in the data analysis, a custom gravimetric calibration factor of 0.30, derived from controlled experiments, was applied to convert the logged nominal instrument readings from uncorrected milligrams per cubic metre to actual milligrams per cubic metre of fine particulate matter PM2.5 from secondhand smoke or background.13

We estimated the annual excess exposure of a full-time casino employee by using data on the average Detroit outdoor background PM2.5 exposure and our measurements of PM2.5 exposure in casinos, by assuming working times of 8 h/day on 250 days/year.

Results

Prior to the implementation of the SFA law in Michigan, the average PM2.5 level found in the 78 restaurants was 126 μg/m3, while the average PM2.5 level in the 77 restaurants after the law was 11.8 μg/m3; this difference between prelaw and postlaw levels is statistically significant (p<0.001). The summary of smoking activities inside the restaurants is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Total number of venues sampled and smoking activity

| Statistics | Prelaw | Postlaw |

|---|---|---|

| Venues sampled | 78 | 77 |

| Total number of persons | 2964 | 4112 |

| Total number of active smokers | 201 | 0 |

| Active smoker density* | 1.11 | 0 |

| Median smoking prevalence, % | 20 | 0 |

*Average number of burning cigarettes per 100 cubic metres.

There were 201 active smokers (burning cigarettes) observed before the law, while no smokers were observed after the law because of the high compliance rate (96%) with the SFA law. The estimated smoking prevalence in each of the 78 restaurants was calculated by multiplying the total number of active smokers for each city by three and dividing by the average number of persons observed during the measurement period.14–16 The estimated smoking prevalence in the cities ranged from 8% to 39.7% before the law. Non-smokers were in the majority in all the cities. The average smoking prevalence for the 78 restaurants was 20.3% before the law was implemented, which is similar to the adult smoking prevalence in Michigan during 2005–2006 (=22.1%) and in 2009 (=19.8%) when these data were collected.

Table 2 shows the average PM2.5 in 78 restaurants in 14 Michigan cities, in addition to the minimum, maximum and the measure of the central tendency.

Table 2.

The average PM2.5 in the restaurants of the 14 cities prelaw and postlaw in Michigan

| Cities | Prelaw (μg/m3) | Postlaw (μg/m3) |

|---|---|---|

| Grand Rapids | 103.1 | 7.5 |

| Kalamazoo | 142.6 | 10.9 |

| Lansing and East Lansing | 81 | 7.4 |

| Midland | 207 | 4.9 |

| Saginaw | 149.7 | 3.4 |

| Ann Arbor | 133 | 15.9 |

| Detroit | 78.6 | 18.7 |

| Flint | 108.6 | 15.2 |

| Novi | 178.3 | 8.8 |

| Marquette | 160.1 | 6.8 |

| Sault Ste Marie | 117.3 | 38.2 |

| Traverse City | 111.1 | 8.6 |

| West Branch | 68.9 | 6.5 |

| Minimum Value | 9 | 1.6 |

| Maximum Value | 601 | 182 |

| Mean, all (SD) | 126 (109)* | 11.8 (22.9)* |

| Median | 90.8 | 6.7 |

| Geometric mean | 88.5 | 7.4 |

| Count | 78 | 77 |

*p Value: <0.0001.

The data are lognormally distributed; however, the arithmetic mean of the data is useful for risk assessment, while the median gives the measure of central tendency for the data, and the geometric mean characterises the fit of the data to the lognormal model. For individual cities, prelaw mean ranges from 9 to 601 μg/m3 with an average of 126 μg/m3. By contrast, the postlaw mean ranges from 1.6 to 182 μg/m3 with an average of 11.8 μg/m3. The outdoor air quality in Michigan during 2007–2011, measured using the US EPA Federal Reference Method, spanned a much smaller range, from 10 to 18 μg/m3, and all measures of central tendency were around 12 μg/m3. It appears that the postlaw indoor (of the 77 restaurants) and outdoor PM2.5 levels are nearly identical, indicating little or no effect from cooking. The prelaw indoor level of PM2.5 in the 78 restaurants was 10.5 times higher than the outdoor levels for Michigan (12 μg/m3), the threshold for good outdoor air quality according to the EPA National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) of 12 μg/m3.17

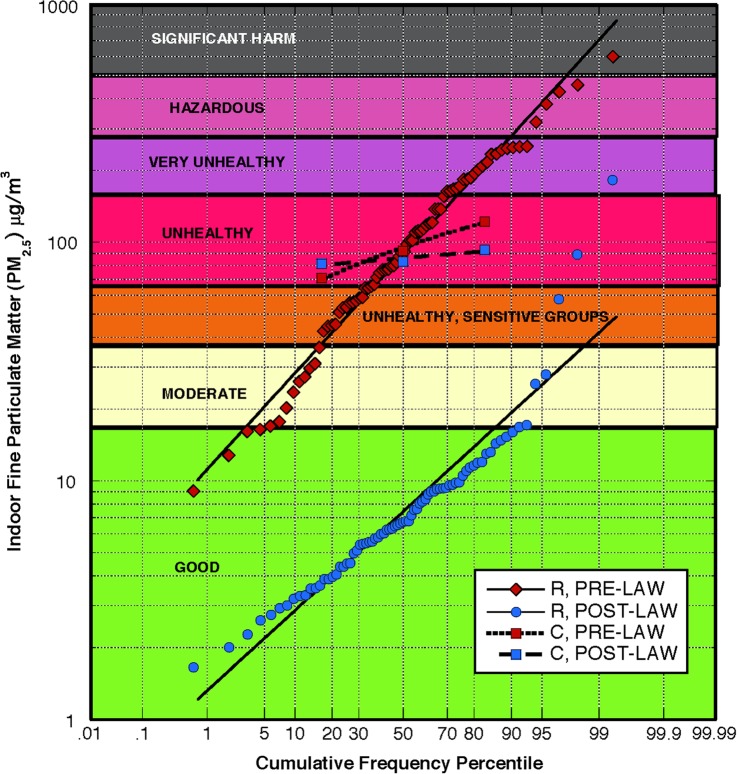

The average PM2.5 level for the casinos was 92 μg/m3 prior to the law and 86 μg/m3 after the law took effect; this difference was not statistically significant. Figure 1 shows the PM2.5 frequency distributions for the three casinos and the 78 restaurants prelaw and postlaw using the Michigan Air Quality Index (AQI) descriptors, from ‘good’ to ‘hazardous’. The prelaw averages are represented by the colour red, while the postlaw averages are indicated by blue.

Figure 1.

PM2.5 frequency distributions for 3 Detroit casinos and 78 restaurants vs Michigan Air Quality Index. The red points indicate prelaw measurements, while blue points indicate postlaw measurements.

The average annual PM2.5 exposure for a full-time employee in the three casinos was 28.9 μg/m3. This level exceeds the 12 μg/m3 EPA NAAQS by 2.4 times.17 We calculated this level by assuming that during the workday, the worker is exposed to (250 d)(8 h/d)(86 μg/m3) =172 000 μg-h/m3; the same employee is exposed only to background particle levels of 12 μg/m3 for 16 h/d during non-work times. Then the worker's background exposure during the workday is (250 d)(16 h/d)(12 μg/m3)=48 000 μg-h/m3, for a total work exposure of 220 000 μg-h/m3 during the year. Then for the remaining 115 days, to background only, yielding an additional exposure of (115 days)(24 h/day)(12 μg/m3)=33 120 μg-h/m3. Therefore, the average annual PM2.5 exposure for a full-time employee in any one of the three casinos is (172 000 μg-h/m3+48 000 μg-h/m3+33 120 μg-h/m3)=253 120 μg-h/m3 per year. However, if the casinos had not been exempted from the ban, the worker's exposure would have been just (365 days)(24 h/day)(12 μg/m3)=105 120 μg-h/m3. Thus, the average casino worker's exposure to PM2.5 air pollution has been increased by a factor of (253 120/105 120)=(2.4).

Figure 1 shows that more than 85% of the restaurants had unhealthy air prior to enactment of the smoke-free law, while less than 5% had unhealthy air afterwards.

For the three Detroit casinos, the same monitoring protocol was used; the SidePak real-time fine particle monitors were deployed by a team of two field volunteers who visited the same three casinos before and after the implementation of the Michigan smoke-free law. Unlike the restaurants and as mentioned, the Detroit casinos were exempted from the law by the state legislature. The PM2.5 was measured on Saturday evenings, prelaw on 18 April 2009, and postlaw on 14 May 2011. Table 3 shows the PM2.5 measurements in the three Detroit casinos. As shown in table 3, the mean PM2.5 was 92 μg/m3 before the law and 85.7 μg/m3 after the law went into effect. Figure 1 shows three readings in red-coloured points before the law and other three readings in blue-coloured points after the law.

Table 3.

PM2.5 measurements in the three Detroit casinos

| Statistics | Prelaw (μg/m3) | Postlaw (μg/m3) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 6.6 | 23.1 | – |

| Maximum | 193 | 281 | – |

| Mean | 92 | 85.7 | 0.52 |

| Median | 94.2 | 85.7 | – |

| SD | (25.8) | (6.19) | – |

| Geometric Mean | 92.6 | 85.6 | – |

Discussion

The average PM2.5 level in 78 restaurants before the implementation of the SFA law was 126 μg/m3. The level was five times higher than the WHO guideline level for 24 h exposure of 25 μg/m3 (WHO, 2006). The level was also 3.6 times higher than the health-based 24 h National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) for outdoor air average of 35 μg/m3 set by the US EPA on 14 December 2012.17

Indoor air quality in 77 restaurants was significantly improved and PM2.5 average level was reduced by 90.6% after the implementation of the Michigan SFA law. The average postlaw indoor PM2.5 level of 11.8 μg/m3 was below both WHO guideline and the NAAQS. Compliance with SFA law is critical to achieving the goal of eliminating exposure to SHS. All restaurants measured in this study complied with the SFA law. The findings in this study indicate that a state-wide law to eliminate smoking in enclosed workplaces and public places substantially reduced PM2.5 levels in all monitored Michigan restaurants, changing the air quality from unhealthy to good.

Effects of comprehensive SFA laws on indoor air quality and public health are clear. However, opponents of smoke-free regulations compromise the health of casino workers by enacting exemptions from the SFA law for the three Detroit casinos. The data for indoor air quality in these casinos clearly indicate unhealthy air before and after the implementation of the law (as shown in figure 1).

Similar results were found in a cross-sectional study of 53 hospitality venues in seven major cities across the USA; this study showed 82% less indoor air pollution in the locations subject to SFA laws while in our study we found 90.6% reduction.18 Lee et al19 found 88% decline in the mean indoor PM2.5 in hospitality venues after the implementation of the comprehensive SFA law in the State of Kentucky; the indoor PM2.5 was significantly reduced from 161 to 20 μg/m3. Repace et al measured the air quality in seven Boston, Massachusetts, pubs before and after Boston's smoke-free law, and found that presmoking-ban PM2.5 levels in those pubs averaged 179 μg/m3, 23 times higher than postban levels, which averaged 7.7 μg/m3. The presmoking ban levels of fine particle air pollution in all the pubs were in the unhealthy to hazardous range of the AQI. Postban air pollution measurements showed 95% reductions in PM2.5 levels.20 A study of changes in indoor air quality in 20 hospitality venues in western New York before and after a state-wide clean indoor air law, showed a postlaw decrease of 84% in average PM2.5 levels.21 Repace studied eight hospitality venues, including one casino in Delaware before and after Delaware's comprehensive smoking ban, and found that levels of PM2.5 decreased by 90% as a result of the smoking ban.22 Jiang et al13 found, in their study measuring the fine particles and smoking activity in a state-wide survey of 36 California Indian casinos, that the average PM2.5 was 63 μg/m3.

By contrast, Repace23 measured an average PM2.5 of 106 μg/m3 higher in a study of three Pennsylvania casinos.

Other studies have directly assessed the effects of SHS exposure on human health. Rapid improvements in the respiratory health of bartenders were seen after California State's SFA law was implemented.24 In Michigan, Wilson et al25 found a significant improvement in the six self-reported respiratory symptoms of bartenders, plus a significant reduction in the mean urinary cotinine and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL) levels, 2 months after the implementation of the smoke-free law. Farrelly et al26 also showed a significant decrease in both salivary cotinine concentrations and sensory symptoms in hospitality workers after New York State's SFA law prohibited smoking in worksites.

A Scottish study of the health impact of the smoking ban on bar workers, found significant early improvements in symptoms, spirometry measurements and systemic inflammation of bar workers. Asthmatic bar workers also had reduced airway inflammation and improved quality of life after the implementation of Scotland's smoke-free legislation in 2006.27

Chronically increased exposure to outdoor PM2.5 is associated with significant increases in heart disease mortality in the general population.28 Pope et al29 concluded that relatively low levels of PM2.5 from either ambient air pollution or SHS are sufficient to increase cardiovascular disease mortality risk. Quantitative estimates of ambient PM2.5 exposure-response and mortality indicate that a daily increase of 10 μg/m3 in outdoor PM2.5 concentrations increases the risk of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) mortality (ICD 10 codes I20-I25) in non-smokers by an average of 18–28% over time to scales ranging from 1 to 18 years (Pope et al). Applying this exposure-response relationship to the exempted casino workers’ exposure yields, an estimated increase in daily exposure of ((12 μg/m3) (2.4)—12 μg/m3)=16.8 μg/m3, for an estimated increase in IHD risk of (16.8 μg/m3/10 μg/m3) (18–28%)=30–47%.

A notable limitation of this study is the fact that a convenience sample was used to select the restaurants included in the study, thus introducing the potential for less objective comparisons than might have occurred in a random sample. Other limitations are that SHS is not the only source of PM2.5 particles and the inability to control for other variables such as ambient particle smoke from cooking, and the presence of table candles. This explains why one out of the six restaurants in Sault Ste Marie city had a high postban concentration of 182 µg/m3, as they had oil candles and were using a smoky grill inside the restaurant during the monitoring process.

Conclusions

This study, the largest single US study of its kind, demonstrates that air quality in Michigan restaurants prior to the SFA law had unhealthy to hazardous levels of indoor air pollution resulting from indoor smoking. The comprehensive SFA law, implemented on 1 May 2010, that prohibited smoking in all public places and places of employment has been shown to decrease exposure to toxic PM2.5 by 90.6%, and yielded good air quality, as shown in figure 1. However, the three Detroit casinos exempted from the SFA law continue to pose a health risk, as demonstrated by the unhealthy levels of fine particle air pollution both before and after the law went into effect. After passing the SFA law, the casino's workers and patrons remained exposed to dangerous air pollution levels.8 In light of the evidence that there is no risk-free level of exposure to SHS, the only safe and proven way to reduce the exposure to these toxic particulates from SHS is by enacting a comprehensive SFA law, without any exemptions, to ensure adequate protection of the health of employees and patrons.1 30

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the local health department staff, coalition members and the volunteers who assisted us in monitoring the restaurants and the casinos, before and after the implementation of the SFA law. We would also like to thank Mikelle Robinson, who was the state tobacco control programme manager at the time of conducting this study for her great support to this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: FS: Planned the concept and design of the study, drafted the protocol, performed the sample selection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafted and submitted the manuscript. TW: Participated in planning of the study, and followed up with data collection, administrative and logistic support, final approval of the article and revision of the manuscript. JK: Participated in planning of the study, and followed up with data collection, obtaining the funding and revision of the manuscript. JR: Participated in planning of the study, revision of protocol, revision of the survey, data collection, entry and analysis, and revision of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported, in part, by cooperative agreements from CDC's Communities Putting Prevention to Work programme (3U58DP001973-01S2).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Michigan Department of Community Health Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A report of the surgeon general: how tobacco smoke causes disease: what it means to you. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Secondhand smoke exposure and cardiovascular effects: making sense of the evidence. Washington: National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.California Environmental Protection Agency. Proposed identification of environmental tobacco smoke as a toxic air contaminant, part B: Health effects. Sacramento, CA: State of California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57:1226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callinan JE, Clarke A, Doherty K et al. Legislative smoking bans for reducing secondhand smoke exposure, smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(4):CD005992 10.1002/14651858.CD005992.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahn EJ. Smokefree legislation: A review of health and economic outcomes research. AM J Prev Med 2010;39(6 Suppl 1):S66–76. 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Repace JL, Jiang RT, Cheng KC et al. Fine particle and secondhand smoke air pollution exposures and risks inside 66 US casinos. Environ Res 2011;111:473–84. 10.1016/j.envres.2011.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluation toolkit for smoke-free policies. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surgeon general's report—how tobacco smoke causes disease: the biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Services. Office of Surgeon General, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann D, Hoffmann I. Chemistry and Toxicology, in Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph 9. Cigars: Health Effects and Trends. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12. U.S. EPA, Fine Particle (PM2.5) Designations, Basic Information. http://www.epa.gov/airquality/particulatematter/designations/basicinfo.htm.

- 13.Jiang RT, Cheng KC, Acevedo-Bolton V et al. Measurement of fine particles and smoking activity in a statewide survey of 36 California Indian casinos. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2011;21:31–41. (open access). http://www.nature.com/jes/journal/vaop/ncurrent/abs/jes200975a.htmlhttp://www.nature.com/jes/journal/vaop/ncurrent/abs/jes200975a.html 10.1038/jes.2009.75http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/jes.2009.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Repace JL. Exposure to secondhand smoke. In: Ott W, Steinemann A, Wallace L, eds. Exposure analysis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2007. Chapter 9 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pritsos CA, Pritsos KL, Spears KE. Smoking rates among gamblers at Nevada casinos mirror US smoking rate. Tob Control 2008;17:82–5. 10.1136/tc.2007.021196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Repace JL, Lowrey AH. Indoor air pollution, tobacco smoke, and public health. Science 1980;208:464–72. 10.1126/science.7367873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA's revised air quality standards for particle pollution: monitoring, designations and permitting requirements. 2013. http://www.epa.gov/pm/2012/decfsimp.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Travers MJ, Hyland A, Repace JL. 7-City Air Monitoring Study (7-CAMS), March-April 2004. Buffalo: Roswell Park Cancer Institute, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee K, Hahn EJ, Robertson HE et al. Strength of smoke-free laws and indoor air quality. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11:381–6. 10.1093/ntr/ntp026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Repace JL, Hyde JN, Brugge D. Air pollution in Boston bars before and after a smoking ban. BMC Public Health 2006;6:266 10.1186/1471-2458-6-266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Indoor air quality in hospitality venues before and after the implementation of a clean indoor air law—Western New York, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53:1038–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Repace JL. Respirable particles and carcinogens in the air of Delaware hospitality venues before and after a smoking ban. J Occup Environ Med 2004;46:887–905. 10.1097/01.jom.0000141644.69355.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Repace JL. Secondhand smoke in Pennsylvania casinos: a study of nonsmokers’ exposure, dose, and risk. Am J Public Health 2009;99:1478–85. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.146241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisner MD, Smith AK, Blanc PD. Bartenders’ respiratory health after establishment of smoke-free bars and taverns. JAMA 1998;280:1909–14. 10.1001/jama.280.22.1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson T, Shamo F, Boynton K et al. The impact of Michigan's Dr. Ron Davis smoke-free air law on levels of cotinine, tobacco-specific lung carcinogen and severity of self-reported respiratory symptoms among non-smoking bar employees. Tob Control 2012;21:593–5. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farrelly MC, Nonnemaker JM, Chou R et al. Changes in hospitality workers’ exposure to secondhand smoke following the implementation of New York's smoke-free law. Tob Control 2005;14:236–41. 10.1136/tc.2004.008839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menzies D, Nair A, Williamson PA et al. Respiratory symptoms, pulmonary function, and markers of inflammation among bar workers before and after a legislative ban on smoking in public places. JAMA 2006;296:1742–8. 10.1001/jama.296.14.1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pope CA III, Dockery DW. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 2006;56:709–42. 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pope CA III, Burnett RT, Krewski D et al. Cardiovascular mortality and exposure to airborne fine particulate matter and cigarette smoke: shape of the exposure-response relationship. Circulation 2009;120:941–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.857888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Guidelines on protection from exposure to tobacco smoke. Article 8 of the FCTC. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, 2007. [Google Scholar]