Abstract

Background and purpose

The incidence of knee osteoarthritis will most likely increase. We analyzed historical trends in the incidence of knee arthroplasty in Sweden between 1975 and 2013, in order to be able to provide projections of future demand.

Patients and methods

We obtained information on all knee arthroplasties in Sweden in the period 1975–2013 from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register, and used public domain data from Statistics Sweden on the evolution of and forecasts for the Swedish population. We forecast the incidence, presuming the existence of a maximum incidence.

Results

We found that the incidence of knee arthroplasty will continue to increase until a projected upper incidence level of about 469 total knee replacements per 105 Swedish residents aged 40 years and older is reached around the year 2130. In 2020, the estimated incidence of total knee arthroplasties per 105 Swedish residents aged 40 years and older will be 334 (95% prediction interval (PI): 281–374) and in 2030 it will be 382 (PI: 308–441). Using officially forecast population growth data, around 17,500 operations would be expected to be performed in 2020 and around 21,700 would be expected to be performed in 2030.

Interpretation

Today’s levels of knee arthroplasty are well below the expected maximum incidence, and we expect a continued annual increase in the total number of knee arthroplasties performed.

Knee and hip osteoarthritis are together ranked in eleventh place as contributors to global disability (as measured in disability-adjusted life years), which is just 1 step below diabetes (Murray et al. 2012). This imposes a significant economic burden on society (Kotlarz et al. 2009). Knee and hip arthroplasty improve quality of life and alleviate the social and economic burden of the disease. Knee arthroplasty was 1 of the 10 most commonly performed procedures in the USA between 2000 and 2004, with the most rapidly increasing hospital costs for all stakeholders (Wilson et al. 2008).

The incidence and prevalence of symptomatic osteoarthritis is likely to increase due to aging of the population and the obesity epidemic (Zhang and Jordan 2010). There are numerous methodological challenges in the study of risk factors for osteoarthritis. Today, only obesity and avoidance of joint injury have gained sufficient evidence to support intervention, and an effective preventative solution to osteoarthritis remains to be found (Johnson and Hunter 2014). The increasing incidence of osteoarthritis prompted Iorio et al. (2008) to set out a 10-item list with strategic implications for all stakeholders, and Fehring et al. (2010) concluded that the number of practicing surgeons will not be able to meet the demands of joint replacement in the immediate future.

For efficient healthcare planning, it is important to forecast the future need for joint replacements—as done in the United States by Kurtz et al. (2005, 2007a, 2007b) and Bini et al. (2011). Few attempts have been made in Europe in general—and in Sweden in particular—to forecast the future need for primary knee arthroplasty. Recently, Nemes et al. (2014) assessed the future need for total hip arthroplasty. Robertsson et al. (2000) assessed the future need for primary knee arthroplasty, with the hypothetical assumption of constant incidence and the main drive behind the increased need being changes in the structure of the Swedish population. However, the incidence in fact doubled during the decade that followed.

In this study, we wanted to predict the future need for knee arthroplasty based on the incidence of these procedures in Sweden between 1975 and 2013.

Methods

Data

We obtained information from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (www.knee.se) on all registered knee arthroplasties in Sweden from 1975 through 2013. This registry has national coverage and a high degree of completeness (Knutson and Robertsson et al. 2010). Publicly available data concerning the evolution of the Swedish population were obtained from Statistics Sweden (www.scb.se). We downloaded historical data from 1975 to 2013, including the number of residents aged 40 years or older. Comparative information about hip arthroplasties was obtained from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (www.shpr.se). Incidence of knee arthroplasty was calculated as the number of new knee arthroplasties per year divided by the total number of Swedish residents who were 40 years or older. We modeled incidence instead of total number of knee arthroplasties to safeguard against changes in the population structure.

Statistics

Historical growth rates were estimated with compound annual growth rate (CAGR). The CAGR is a geometric progression ratio that estimates the smoothed annual growth rate by taking into consideration the values at the beginning and the end of the time period under study. CAGR is calculated as

and aids comparison of growth rates over time (Pabinger and Geissler 2014).

Possible changes in growth in incidence and the time point when this change(s) occurred were assessed with piecewise linear regression splines (Muggeo 2003).

Swedish residents who are 40 years or older represent the majority of primary knee arthroplasty patients (SKAR 2014), so we estimated the incidence of primary knee arthroplasty per 105 Swedish residents aged 40 years or more. The estimated incidence served as outcome for the regression modeling while calendar year served as input. The regression models were built in order to forecast the incidence of primary knee arthroplasties surgeries per 105 Swedish residents aged 40 years or more in the decades after 2013, and to estimate the maximum incidence per 105 Swedish residents aged 40 years or more. We adapted the regression framework used by Nemes et al. (2014) and attempted to estimate the maximum incidence empirically from 3 competing models. These were asymptotic, logistic, and Gompertz regression (Turner et al.1961,1969, Park and Lim 1985) with nonlinear least-squares with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (Moré 1978) and a brute-force grid search. The common denominator of these 3 models is the existence of an upper asymptote, the projected maximum incidence for knee arthroplasty. Beyond that, the 3 models differ in philosophy. The asymptotic model assumes a growth rate that is proportional at any time to the maximum incidence yet to be reached. The logistic model assumes exponential growth at the beginning. It has an inflection point at half of the projected maximum incidence. When the inflection point is passed, the growth decelerates. The model fits a sigmoid curve to the data, which is symmetric around the inflection point. The Gompertz model is similar to the logistic one, but it relaxes the symmetry assumption and its inflection point occurs at around 37% of the projected maximum incidence.

We compared competing models with the Akaike Information Criterion for small samples (AICc) and Akaike weights (wAIC) (Bozdogan 1987, Wagenmakers and Farrell 2004). Akaike weights were also used to calculate a weighted average of the estimated asymptote and predicted incidence, thus giving estimates that incorporate model uncertainty (Lukacs et al. 2010, Symonds and Moussalli 2011).

As these models cannot explicitly account for the effect of changes in age and sex through the history of knee arthroplasty, we undertook a stratified analysis. The data were stratified for sex and separate models were fitted for females and males. Ideally, we should have stratified different age groups too. Despite the fact that the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register is one of the largest and oldest of its kind, one should remember that it contains data from less than 40 years. In addition, relatively small numbers of operations in the first decades after the introduction of knee arthroplasty and the fluctuation of the age group frequencies hindered stratification for age groups as well. While the frequency of the most common age group to undergo knee arthroplasty (65–74 years) is relatively stable, the frequencies of other age groups fluctuate considerably depending on the year of operation (SKAR 2014).

Statistical analyses were performed using in R software release 3.1.0.

Results

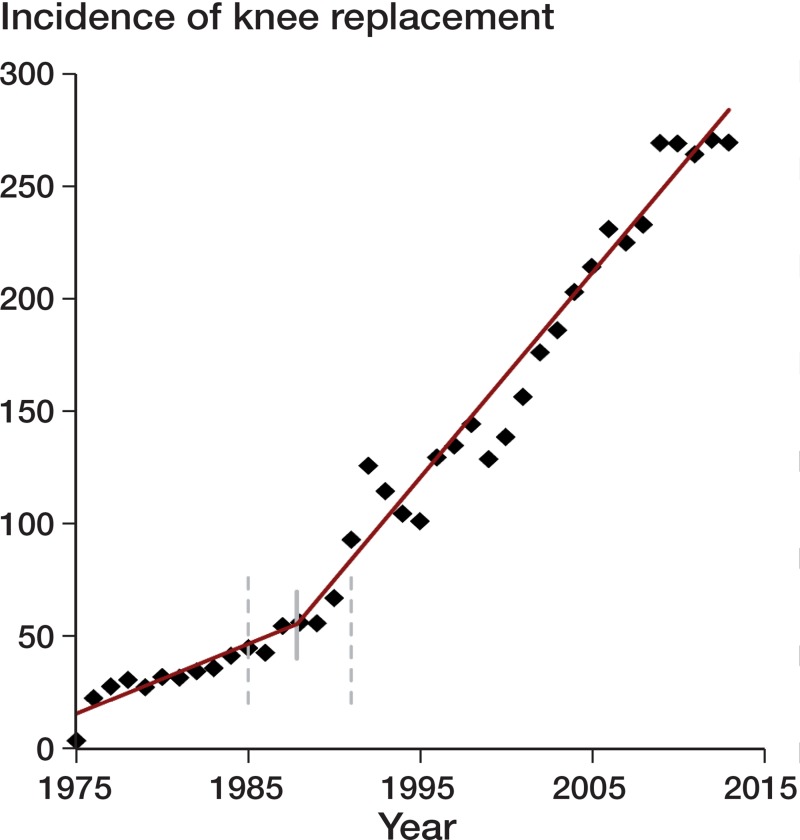

From its start in 1975 until the end of 2013, the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register had recorded 214,802 primary knee arthroplasties. The magnitude of the growth rate changed in 1988 (95% CI: 1985–1991) (Figure 1). Before 1988, the incidence increased by 2.8 (CI: 1.1–4.7) per year. Thereafter, the increase in incidence was higher and amounted to 9.1 (CI: 8.4–9.7) per year.

Figure 1.

Incidence of primary knee arthroplasty in Swedish residents aged 40 years or more, from the introduction of the procedure until the end of 2013, and the estimated time point (1988) and associated 95% confidence intervals when the growth rate of the incidence changed. The black diamonds represent the observed incidence and the red line is the fitted regression line.

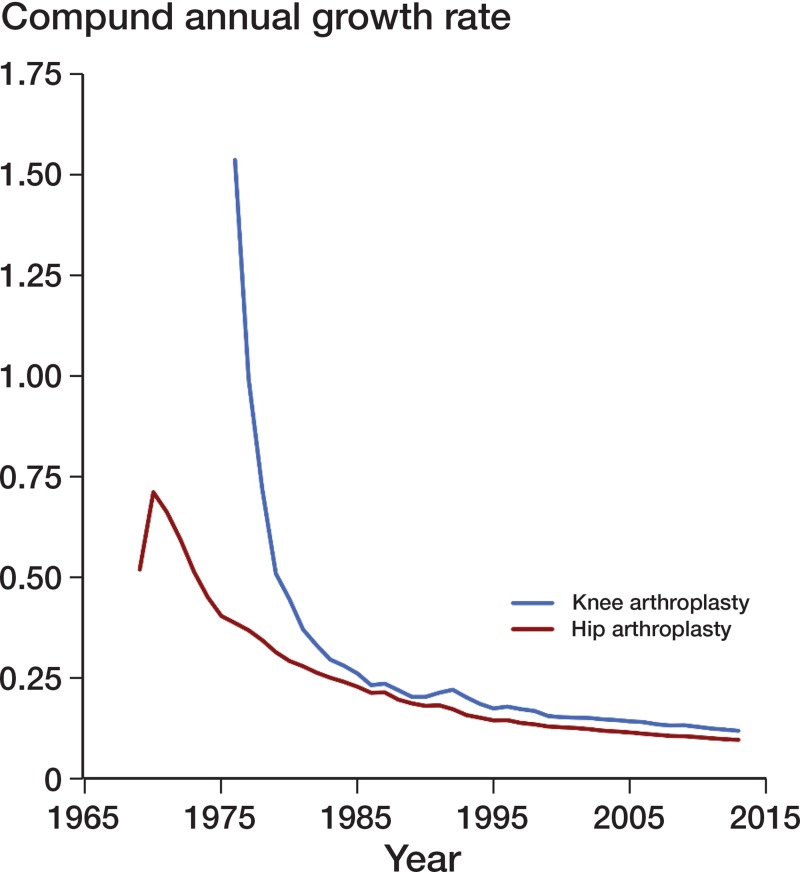

In 1975, only 128 primary knee arthroplasties were performed, with an incidence of 3.5 per 105 Swedish residents aged 40 years or more. By 1985, there had been a 16-fold increase to 1,979 operations per year (with an incidence of 45). Between 1985 and 1995, the annual number of operations almost tripled to 4,302 (incidence 101). Between 1995 and 2005, the annual number of surgeries roughly doubled to 9,796 (incidence 203). From 2005 onward, the increase slowed down and in 2013, 13,338 operations were performed with an incidence of 268 operations per 105 Swedish residents aged 40 years or more. The compound annual growth rate of primary knee replacement operations exceeded the growth rate of hip replacement operations through the whole study period (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Compound annual growth rate for primary knee arthroplasty and the comparative values for hip arthroplasty in Sweden.

Asymptotic regression did not converge and failed to produce parameter estimates, so this model was dropped.

Maximum incidence estimates from the 2 converging competing models varied considerably. Gompertz regression was the most liberal (697, CI: 484–1,335) and logistic regression was the most conservative (377, CI: 327–464).

Both models fitted the data well, with calendar year explaining 98.3% of the total variation observed in knee arthroplasty incidence for logistic regression and 98.2% for Gompertz regression.

There was no unequivocal support for either model. The probability of being the best model given the data and competing models was 0.711 for logistic regression and 0.289 for Gompertz regression. Thus, we calculated the weighted average of maximum incidence estimates across the 2 models.

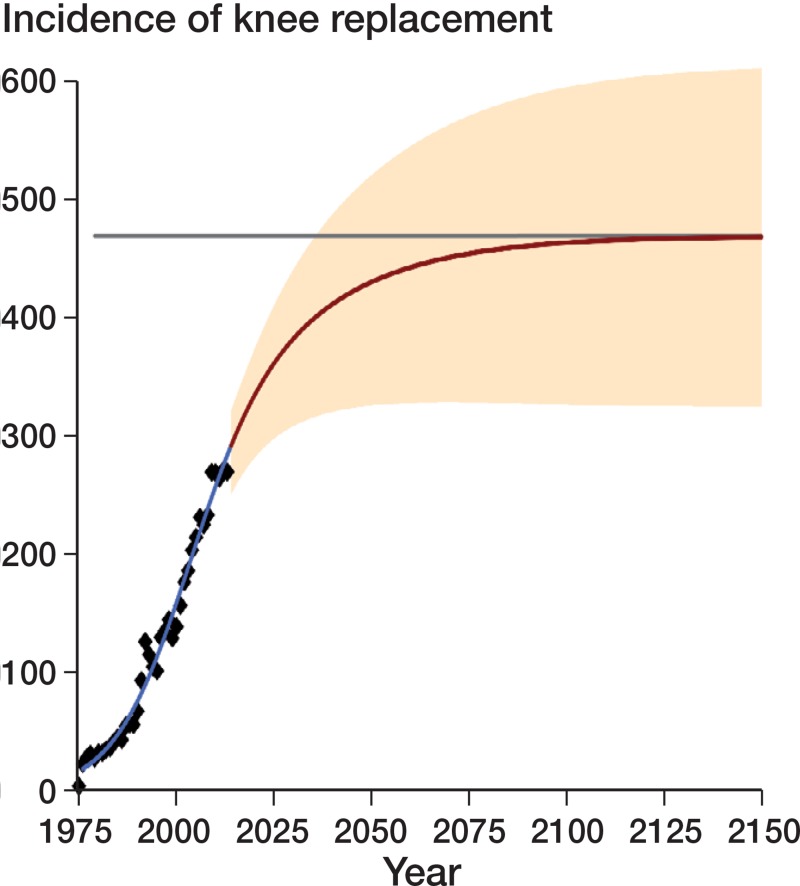

The averaged upper incidence of 469 (CI: 132–807) will be reached somewhere around the middle of the twenty-second century (Figure 3). In 2020, the estimated incidence of total knee arthroplasty per 105 Swedish residents aged 40 years or more will be 334 (95% prediction interval (PI): 281–374) and in 2030 it will be 382 (PI: 308–441). Using official forecasted population growth data, around 17,500 operations would be expected to be performed in 2020 and around 21,700 would be expected to be performed in 2030. The Table gives an overview of the estimated future need for primary knee arthroplasties in the coming decades.

Figure 3.

The recorded and projected incidence of knee arthroplasty per 105 Swedish residents aged 40 years or more. The gray horizontal line represents the highest primary knee arthroplasty incidence estimated. The red line represents the projected number of knee arthroplasties with associated 95% prediction intervals. The black diamonds represent the incidence observed and the blue line is the fitted regression line.

Prognosis for the evolution of the Swedish population between 2014 and 2030: the expected number and proportion of Swedish residents aged 40 years or more together with the predicted incidence of primary knee arthroplasty (PKA) per 105 Swedish residents aged 40 or more and the predicted number of future primary knee arthroplasties

| Year | Total population | Population > 40 years | Proportion > 40 years | Incidence | 95% PI | Predicted no. of PKAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 9,747,069 | 4,996,777 | 0.513 | 292 | 250–321 | 14,591 |

| 2015 | 9,856,598 | 5,046,523 | 0.512 | 300 | 257–331 | 15,140 |

| 2016 | 9,961,439 | 5,091,204 | 0.511 | 307 | 263–340 | 15,630 |

| 2017 | 10,053,393 | 5,132,502 | 0.511 | 314 | 268–348 | 16,116 |

| 2018 | 10,138,869 | 5,171,273 | 0.510 | 321 | 273–357 | 16,600 |

| 2019 | 10,218,226 | 5,212,767 | 0.510 | 328 | 277–366 | 17,098 |

| 2020 | 10,292,244 | 5,256,236 | 0.511 | 334 | 281–374 | 17,556 |

| 2021 | 10,359,520 | 5,295,060 | 0.511 | 340 | 285–381 | 18,003 |

| 2022 | 10,420,903 | 5,333,289 | 0.512 | 346 | 289–389 | 18,453 |

| 2023 | 10,477,689 | 5,369,767 | 0.512 | 351 | 292–397 | 18,848 |

| 2024 | 10,53,0849 | 5,407,595 | 0.514 | 357 | 295–404 | 19,305 |

| 2025 | 10,581,134 | 5,448,506 | 0.515 | 361 | 298–411 | 19,669 |

| 2026 | 10,628,190 | 5,490,693 | 0.517 | 366 | 300–417 | 20,096 |

| 2027 | 10,672,333 | 5,533,310 | 0.518 | 370 | 302–424 | 20,473 |

| 2028 | 10,713,499 | 5,580,992 | 0.521 | 375 | 305–430 | 20,929 |

| 2029 | 10,751,868 | 5,630,101 | 0.524 | 379 | 306–436 | 21,338 |

| 2030 | 10,787,725 | 5,684,406 | 0.527 | 382 | 308–441 | 21,714 |

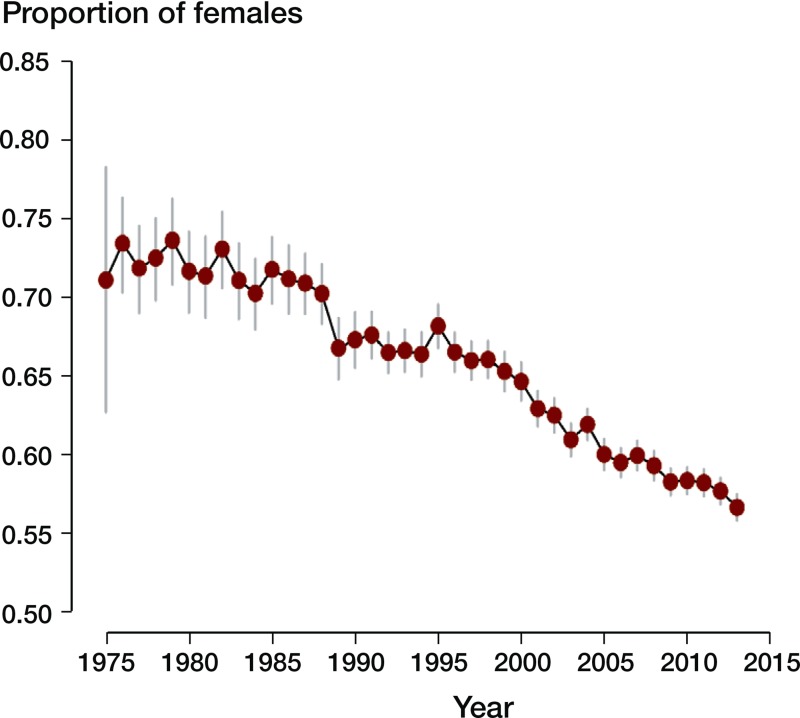

Historically, women have predominated among knee arthroplasty patients, but the sex disparity has gradually decreased (Figure 4). Stratified analysis forecast that a maximum of 466 (95% PI: 223–709) of every 105 Swedish women aged 40 or more would be expected to have knee arthroplasty in the future. In 2020, around 360 (PI: 308–401) of every 105 Swedish women aged 40 or more will undergo knee arthroplasty while in 2030, the figure will be 401 (PI: 333–458). Using officially forecast data, this would mean 9,673 operations in 2020 and 11,606 2030.

Figure 4.

Proportion of female patients who underwent knee arthroplasty and the associated 95% confidence intervals from 1975 until 2013. There was a significant decreasing trend, but females still predominate. Trend test: χ2 = 1722.02, p < 0.0001

Stratified analysis for men forecast that 426 (PI: 23–830) of every 105 Swedish men aged 40 or more would be expected to have knee arthroplasty in the future. In 2020, around 304 (PI: 254–342) of every 105 Swedish men aged 40 or more will undergo knee arthroplasty while in 2030, the figure will be 352 (PI: 277–412). Using officially forecast data, this would mean 7,843 operations in 2020 and and 9,842 operations in 2030.

Discussion

If current trends continue, we could expect that annually up to 462 of 105 Swedish residents aged 40 years or more will undergo primary knee arthroplasty. The number of primary knee arthroplasties performed annually will increase from the current 13,338 operations to around 21,700 in 2030. This increase in the number of knee arthroplasties is due to the increase in the population, to the rising proportion of Swedish residents aged 40 or more, and to the extended indications for the procedure.

The increase in primary knee arthroplasties was higher than for primary hip arthroplasties, though it started at a slightly lower value. In 2013 in Sweden, 13,338 primary knee arthroplasties were performed whereas there were 16,333 hip arthroplasty operations. There appears to be a consensus among the orthopedic profession that the number of primary knee arthroplasties will exceed the number of hip arthroplasties in most countries. This consensus is reinforced by the findings of Cross et al. (2014), who estimated the age-standardized global prevalence of knee osteoarthritis to be 3.5% and the prevalence of hip osteoarthritis to be 0.85%. The incidences of knee and hip osteoarthritis both tend to increase with age, and the aging of the population will most probability result in an increasing number of joint arthroplasties being performed, even though the incidence of these procedures may remain the same.

The historically lower incidence of primary knee arthroplasty compared to hip arthroplasty can partly be attributed to later introduction, later development of well-functioning implants, and differences in the complexities of surgery.

Compared to the knee joint, the hip joint is relatively simple and arthroplasty operations have the potential to restore full mobility and functionality. While joint prostheses were developed in the nineteenth century, the medical breakthrough for hip prostheses happened in 1963 when Charnley introduced his “low friction” cemented prosthesis. A similar breakthrough for knee prostheses had to wait until 1974, when the Total Condylar knee prosthesis was introduced (Ranawat 2002). The anatomical complexities of the knee joint and delay in availability of reliable prostheses led to the conception of more difficult surgery, which resulted in lower numbers of hospitals/surgeons offering knee arthroplasty operations. Despite the many advances since the introduction of knee arthroplasty, one-fifth of patients are not satisfied with the outcome (Bourne et al. 2010). The result in Sweden was that general practitioners and patients opted for knee arthroplasty only when absolutely necessary, due uncertainty about the results and the fear of severe complications in difficult cases and after revision. Until the late 1980s, there was no general consensus that knee arthroplasty actually can be a life changing operation. This, in combination with improved methods in anesthesia, resulted in a rapid increase in knee arthroplasties, and this increase can be expected to continue in the coming decades.

Increasing body mass index (BMI) in many countries and the higher incidence and prevalence of knee osteoarthritis also supports the notion that primary total knee arthroplasties will outnumber primary total hip arthroplasties. Whether or not increased awareness and use of non-surgical and joint-preserving treatments for osteoarthritis can change this scenario remains to be seen.

In the USA, per-capital use of primary knee arthroplasties grew due their availability (Medicare enrollment) (Cram et al. 2012), and this increase appears to have been immune to the recent economic downturn (Kurtz et al. 2014). Increased demand for primary knee arthroplasty is not limited to the western world; similar trends have also been observed in South Korea (Koh et al. 2013). With countrywide public healthcare coverage, we expect that the incidence of primary knee arthroplasty will grow in Sweden. How well the estimated 462 per 105 Swedish residents aged 40 years or more represents the maximum incidence is difficult to judge. Kurtz and collaborators (Kurtz et al. 2014) updated their previous projections of demand for joint replacement in the United States and found reasonable agreement with the previous projections, which were based on a more limited dataset (Kurtz et al. 2007a). Nemes et al. (2014) forecast that there would be 16,021 total hip replacements in 2013, while the actual number was 16,333. Since currently only a 1-year forecast can be matched with actual data, it is difficult to judge whether there is a substantial deviation, especially if the actual number of surgeries is within the prediction intervals. Forecasts of future treatment demand attract relatively limited interest compared to economic forecasts. As a consequence, we still lack empirical results on which method best predicts future demand. Thus, instead of a knowledge-driven model selection we resorted to a data-driven selection. As this was inconclusive, we opted for a model-averaging strategy that considers all models, with the final estimates incorporating the uncertainty in model selection. This has long been considered the way to go in the economic literature, with the premise that a combination of forecasts will outperform individual forecasts (Bates and Granger 1969). However there is no consensus regarding the ideal combination technique (Moral-Benito 2013).

As Nemes et al. (2014) described, the accuracy of projections of future demand may be influenced by an array of factors. These authors noted that the assessment criteria for the feasibility of joint arthroplasty has changed. The structure of the population has changed; not only has the proportion of Swedish citizens aged 40 or more increased and keeps increasing, but the population has become more heterogeneous due to increased immigration. The disparity between the sexes is starting to even out. While women have predominated among knee arthroplasty patients in the past, more and more men are being operated. Stratified analysis for sex led to similar results as with unstratified analysis. However, there were discrepancies in the maximum incidence and projected incidence in the distant future. This could be due to better projection from consideration of sex disparity in knee arthroplasty. As stratification further reduced the small number of procedures in the 1970s and the beginning of 1980s, unwanted uncertainty was introduced, which led to widened confidence intervals for the estimated incidences.

The proportion of obese people appears to be increasing (Neovius et al. 2013), and this is accentuated in people with mobility-related disability (Holmgren et al. 2014), who might benefit most from joint arthroplasty. Lighter assessment criteria, increase in sedentary lifestyle, and increasing BMI may led to an increased demand for knee arthroplasty—thus making the present estimates too conservative. Nationwide commitments such as the BOA registry (better management of patients with osteoarthritis) are aimed at offering patients with osteoarthritis information and exercise according to the evidence-based recommendations, to ensure that surgical interventions are only considered if non-surgical treatment has been tried and has failed (Thorstensson et al. 2014). The BOA initiative may reduce the demand for knee arthroplasty, but by how much remains to be seen.

In summary, our findings corroborate previous findings from the USA indicating that there will be increased demand for primary knee arthroplasty. One major drive behind this increase is the aging Swedish population. We also expect an additional increase due to partly unknown causes, where changes in lifestyle and probably also availability would have an influence. Altogether, this means that today’s incidence levels can be expected to be far from the projected maximum.

Acknowledgments

No competing interests declared.

SN, ORob, ORol, and GG contributed to the conception and the design of the study. ORob, AWD and MS contributed to the acquisition of data. Statistical analyses were run by SN who also drafted the manuscript. All authors interpreted results, revised critically, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Bates JM, Granger CWJ. The combination of forecasts. OR. 1969;20(4):451–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bini SA, Sidney S, Sorel M. Slowing demand for total joint arthroplasty in a population of 3.2 million . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(6):124–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne R, Chesworth B, Davis A, Mahomed N, Charron KJ. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdogan H. Model selection and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)—The general-theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):345–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991–2010 . JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227–36. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study . Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1323–30. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehring TK, Odum SM, Troyer JL, Iorio R, Kurtz SM, Lau EC. Joint replacement access in 2016: a supply side crisis . J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:1175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren M, Lindgren A, de Munter J, Rasmussen F, Ahlstrom G. Impacts of mobility disability and high and increasing body mass index on health-related quality of life and participation in society: a population-based cohort study from Sweden . BMC Public Health. 2014;14:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio R, Robb WJ, Healy WL, Berry DJ, Hozack WJ, Kyle RF, et al. Orthopaedic surgeon workforce and volume assessment for total hip and knee replacement in the united states: Preparing for an epidemic . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2008;90-A(7):1598–605. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VL, Hunter DJ. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis . Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson K, Robertsson O. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (www.knee.se) The inside story . Acta Orthop. 2010;81:5–7. doi: 10.3109/17453671003667267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh IJ, Kim TK, Chang CB, Cho HJ, In Y. Trends in use of total knee arthroplasty in Korea from 2001 to 2010 . Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2013;471(5):1441–50. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2622-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotlarz H, Gunnarsson CL, Fang H, Rizzo JA. Insurer and Out-of-Pocket Costs of Osteoarthritis in the US Evidence From National Survey Data . Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(12):3546–53. doi: 10.1002/art.24984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S, Mowat F, Ong K, Chan N, Lau E, Halpern M. Prevalence of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 1990 through 2002 . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87A(7):1487–97. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030 . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007a;89-A(4):780–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, Mowat F, Saleh K, Dybvik E, et al. Future clinical and economic impact of revision total hip and knee arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007b;89-A:144–51. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the Economic Downturn on Total Joint Replacement Demand in the United States . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2014;96-A:624–30. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs PM, Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model selection bias and Freedman’s paradox. Ann Inst Stat Math. 2010;62(1):117–25. [Google Scholar]

- Moral-Benito E. Model averaging in economics: and overview. Journal of Economic Surveys. 2013 DOI: 10.1111/joes.12044. [Google Scholar]

- Moré J. The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm: Implementation and theory. In: Numerical analysis. (Ed. Watson GA) Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 1978;630:105–16. [Google Scholar]

- Muggeo V MR. Estimating regression models with unknown break-points . Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22(19):3055–71. doi: 10.1002/sim.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions 1990–2010 . The Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemes S, Gordon M, Rogmark C, Rolfson O. Projections of total hip replacement in Sweden from 2013 to 2030 . Acta Orthop. 2014;85(3):238–43. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.913224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neovius K, Johansson K, Kark M, Tynelius P, Rasmussen F. Trends in self-reported BMI and prevalence of obesity 2002–10 in Stockholm County, Sweden . Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(2):312–5. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabinger C, Geissler A. Utilization rates of hip arthroplasty in OECD countries . Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(6):734–41. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EW, Lim SM. Empirical estimation of the asymptotes of disease progress curves and the use of the Richards generalized rate parameters for describing disease progress. Phytopathology. 1985;75(1):786. [Google Scholar]

- R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2014; Vienna, Austria: R Core Team. R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- Ranawat CS. History of total knee replacement. J South Orthop Assoc. 2002;11(4):218–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Dunbar MJ, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Past incidence and future demand for knee arthroplasty in Sweden - A report from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register regarding the effect of past and future population changes on the number of arthroplasties performed . Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:376–80. doi: 10.1080/000164700317393376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKAR. Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2014. 2014. ISBN 978-91-979924-8-0.

- Symonds M RE, Moussalli A. A brief guide to model selection, multimodel inference and model averaging in behavioural ecology using Akaike’s information criterion. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2011;65(1):13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Thorstensson CA, Garellick G, Rystedt H, Dahlberg LE. Better management of patients with osteoarthritis. Development and nationwide implementation of an evidence-based supported osteoarthritis self-management programme . Musculoskeletal Care. 2014 doi: 10.1002/msc.1085. doi: 10.1002/msc.1085. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner ME, Monroe RJ, Lucas HL., Jr Generalized asymptotic regression and non-linear path analysis. Biometrics. 1961;17(1):120–43. [Google Scholar]

- Turner ME, Jr, Blumenstein BA, Sebaugh JL. A generalization of the logistic law of growth . Biometrics. 1969;25(3):577–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmakers EJ, Farrell S. AIC model selection using Akaike weights . Psychon Bull Rev. 2004;11(1):192–6. doi: 10.3758/bf03206482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NA, Schneller ES, Montgomery K, Bozic KJ. Hip and knee implants: current trends and policy considerations . Health Affairs. 2008;27:1587–98. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.6.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis . Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26:355–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]