Abstract

Background and purpose

Postoperative anterior knee pain is one of the most frequent complications after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Changes in patellar kinematics after TKA relative to the preoperative arthritic knee are not well understood. We compared the patellar kinematics preoperatively with the kinematics after ligament-balanced navigated TKA.

Patients and methods

We measured patellar tracking before and after ligament-balanced TKA in 40 consecutive patients using computer navigation. Furthermore, the influences of different femoral and tibial component alignment on patellar kinematics were analyzed using generalized linear models.

Results

After TKA, the patellae shifted statistically significantly more laterally between 30° and 60°. The lateral tilt increased at 90° of flexion whereas the epicondylar distance decreased between 45° and 75° of flexion. Sagittal component alignment, but not rotational component alignment, had a significant influence on patellar kinematics.

Interpretation

There are major differences in patellar kinematics between the preoperative arthritic knee and the knee after TKA. Combined sagittal component alignment in particular appears to have a major effect on patellar kinematics. Surgeons should be especially aware of altering preoperative sagittal alignment until the possible clinical relevance has been investigated.

Postoperative anterior knee pain is one of the most frequent complications after total knee arthroplasty (TKA), and patellar maltracking has been mentioned as the reason in some recent investigations (Miller et al. 2001b, Kienapfel et al. 2003, Heinert et al. 2011). In vivo studies of patellar kinematics have been conducted on the natural knee using radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging, and bone pins or fluoroscopy and MRI for the replaced knee joint (Stiehl et al. 1995, Katchburian et al. 2003, von Eisenhart-Rothe et al. 2004, Lee et al. 2005). Several authors have emphasized that the occurrence of patellar maltracking is caused by rotational malalignment of the femoral and/or tibial component (Hefzy et al. 1992, Barrack et al. 2001, Miller et al. 2001a, Siston et al. 2005, Belvedere et al. 2007, Luring et al. 2007, Kessler et al. 2008, Steinbrück et al. 2013). Recent studies have shown that femoral internal rotation contributes to altered patellofemoral kinematics and the occurrence of anterior knee pain (Berger et al. 1998, Kienapfel et al. 2003, Farrokhi et al. 2011). In a radiological investigation, Berger et al. (1998) stated that combined internal rotation of the femoral and tibial components correlates directly with the severity of postoperative patellofemoral complications. Furthermore, some authors have reported that the rotation of the femoral component according to the trans-epicondylar line results in better restoration of physiological patellar kinematics than the orientation according to Whiteside’s line or 3° external relative to the posterior condyles (Olcott and Scott 1999, Miller et al. 2001a, Luring et al. 2007). However, we have found only 2 investigations that measured patellar kinematics before and after TKA in vivo using the accuracy of computer navigation (Anglin et al. 2008, Belvedere et al. 2014). These studies involved small patient populations and there was no definition of component orientation. To date, no comparisons of patellar kinematics between the preoperative arthritic knee and the knee after ligament-balanced navigated TKA have been published.

Presently, it is not clear to what extent patellar kinematics of the initial preoperative arthritic knee change after ligament-balanced TKA using computer navigation. We therefore investigated the difference in patellar kinematics between the arthritic knee and the knee after ligament-balanced TKA, using an image-free navigation system. This was based on the findings of Heesterbeek et al. (2011), who stated that ligament-balanced femoral component rotation is not associated with abnormal postoperative patellar position in a radiological investigation. Furthermore, we measured intraoperative axial and sagittal femoral and tibial component alignment, and its influence on patellar kinematics was analyzed using generalized linear models. This concept presented—analysis of combined component alignment and its effect on patellar kinematics intraoperatively using patellar navigation—could help to prevent maltracking of the patella and therefore postoperative complications. In addition, apart from patellar shift, tilt, and rotation, epicondylar distance was used and treated as a new kinematic parameter.

Patients and methods

For this exploratory, hypothesis-generating investigation we recruited 46 patients with primary osteoarthtitis of the knee (Kellgren and Lawrence grade III–IV) who were designated for TKA and who received a standard, cemented, cruciate retaining TKA with a fixed platform (PFC Sigma; DePuy, Warsaw, IN) using conventional ligament-balanced technique and computer navigation, including intraoperative patellar tracking (BrainLAB, Feldkirchen, Germany). Patients with a varus/valgus deformity of more than 15°; sagittal or medio-lateral instability of more than 5 mm (grade 1+); extension deficiency; contracted, insufficient, or missing posterior cruciate ligament; tibial or femoral bone loss; previous patella dislocation; or previous surgical intervention on the relevant knee were excluded. Altogether, 6 patients were excluded. The study population therefore consisted of 40 patients (21 of them men) with an average age at the time of surgery of 65 (47–89) years. No patella replacements were used, and no other surgical patellar interventions such as lateral release or patelloplasty were performed before measurements, in order to achieve equivalent conditions before and after TKA. The optical computer navigation system used has been verified to be a reliable measurement tool for evaluation of 3-dimensional tibiofemoral and patellofemoral kinematics with an accuracy of 0.1 mm and 0.1° (Griffin et al. 2000, Lee et al. 2010).

Surgical procedure and data collection

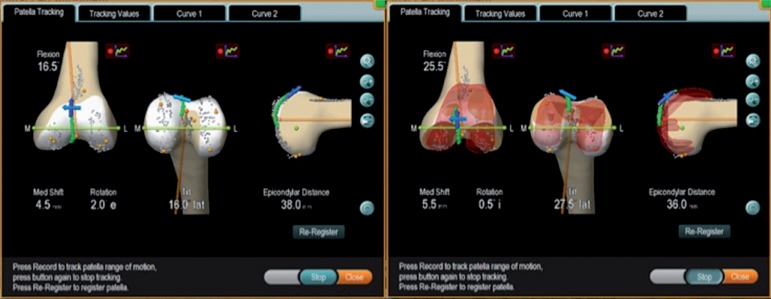

After a midline skin incision, a standard medial parapatellar approach was used. The capsule was marked at standardized locations to ensure later anatomical reconstruction. 2 passive optical reference arrays were secured on the distal medial femur and the proximal medial tibia. The femoral array was attached through an additional 1-cm incision to avoid soft tissue tension during patellar tracking. After referencing the center of the hip by circumduction, the landmarks needed for femorotibial kinematics by the navigation system were digitized. The line connecting the middle of the posterior cruciate ligament to the medial border of the patellar tendon attachment was defined as the tibial a.p. axis according to Akagi et al. (2004). The patellar array was fixed onto the anterior side of the patella by a small screw (Figure 1). A point at the medial, superior, and inferior edge and at the middle of the posterior articular ridge of the patella defined the patella coordinate frame, as recommended by the manufacturer (BrainLab). After anatomical closure of the joint capsule, the natural patellar kinematics and the relative orientation between femur, tibia, and patella were recorded between 30° and 90° of flexion during passive motion (Figure 2). The position of the registered patella coordinate frame relative to the coordinate frame of the femur was calculated by the navigation system during the motion cycle. Both, absolute, and relative values for patellar mediolateral shift (medial: +, lateral: −), axial tilt (medial: −, lateral: +), and coronal rotation (external: −, internal: +) of the patella were collected. In addition, the epicondylar distance describing the line from the previously chosen point at the middle of the posterior articular ridge of the patella perpendicular to the trans-epicondylar line, which is built from the registered femoral epicondyles, was measured during the motion cycle. Figure 2 shows the epicondylar distance before and after TKA was performed, which is represented by green dots in the sagittal view. This distance gives information about the anterior-posterior position of the patella throughout the flexion cycle in relation to the femur. After removal of osteophytes at the medial and lateral compartments, the tibial cut was performed and a double tensiometer inserted at 0° of extension and 90° of flexion with a distraction force of 90 N. In the frontal plane, zero degrees between the femoral and tibial mechanical axis was aimed at. The flexion gap was adapted through bony cuts by the navigation software to achieve ligament balancing. No ligament release was necessary due to well-aligned knees. The femoral component rotation was set by ligament balancing and the rotation of the tibial component was set to the medial third of the tibial tubercle (Berger et al. 1998). A second measurement of patellar kinematics was performed after standardized prosthesis implantation with recommended component placement by the navigation system, as previously published (Bäthis et al. 2006), and with the natural patella without any previously performed surgical patellar intervention. During measurements, the limbs were lifted vertically at the distal femur by the surgeon without touching the tibia, performing 2 repetitions of the motion cycle. Because of missing muscle tone and floppy patellae, values up to 30° of flexion were irregular and were removed from the experimental protocol. Also, definitive femoral component rotation and flexion and tibial component rotation and slope were recorded intraoperatively. The data measured were analyzed using a patellar tracking software application for TKA (Patellar Tracking; BrainLab).

Figure 1.

Intraoperative setup.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of patellar tracking in the arthritic knee (left panel) and after TKA (right panel).

Statistics

Due to the exploratory nature of the trial, no formal sample size calculation was performed a priori. To obtain robust and accurate estimates of the effects investigated, 40 patients were recruited for analysis. Preoperative and postoperative values were compared by means of paired t-test and they are presented as mean difference (SD) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Generalized linear models with tibiofemoral flexion as fixed effect and interception as random effect were used to assess the influence of femoral and tibial component alignment on patellar kinematics. Interaction terms between component alignments and tibiofemoral flexion were added if a statistically significant main or interaction effect was found. Any p-value of < 0.05 was taken to signify statistical significance. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0, R version 3.0.2, and SAS version 9.3.

Ethics

This study was approved by the local ethical committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Regensburg and all volunteers gave their informed written consent (Ethics Committee Approval no. 12-101-0208).

Results

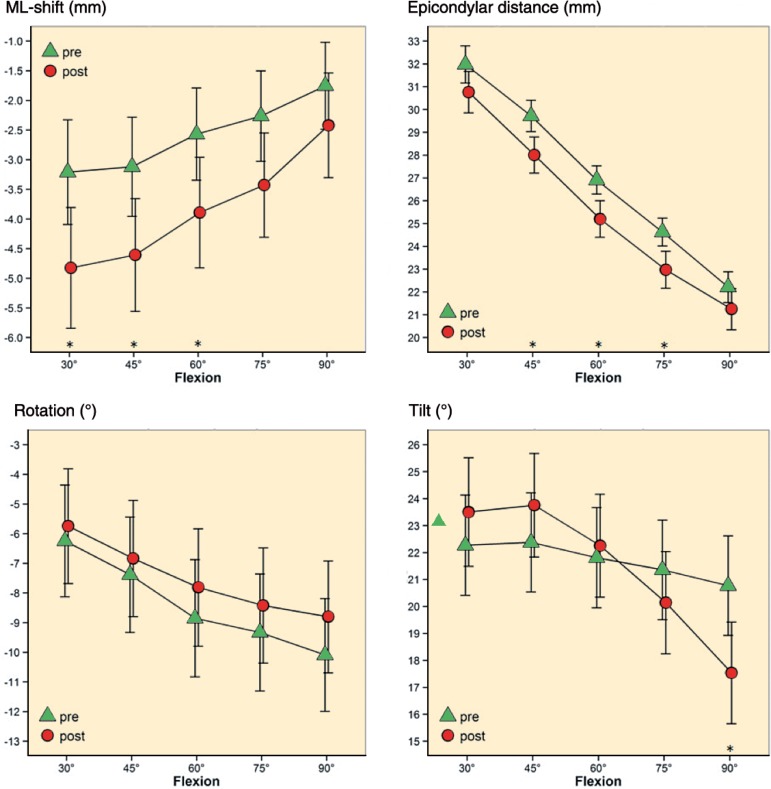

There was a statistically significant difference between preoperative and postoperative mediolateral patellar shift between 30° and 60° of flexion; postoperatively, the patellae shifted more laterally throughout the whole motion cycle compared to the arthritic knee. Interestingly, a decrease in epicondylar distance during the whole motion cycle with significant values between 45° and 75° of flexion was observed after TKA. After implantation, the patellae tilted more laterally at flexion angles between 30° to 60°. However, from 60° to 90° of flexion, the patellae tilted more medially compared to the preoperative values—with statistical significance at 90°. Furthermore, the patellae rotated more medially at all flexion angles after TKA, but this was not statistically significant (Table 1, Figure 3).

Table 1.

Pre- vs. postoperative patellar tracking (lateral shift: +; reduction in epicondylar distance: +; internal rotation: −; lateral tilt: −)

| Flexion | Mean differ-ence (SD) | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shift | 30° | 1.6 (4.2) | 0.2 to 2.9 | 0.02 |

| 45° | 1.4 (4.2) | 0.1 to 2.8 | 0.03 | |

| 60° | 1.3 (4.1) | 0.0 to 2.6 | 0.04 | |

| 75° | 1.1 (4.2) | –0.1 to 2.5 | 0.1 | |

| 90° | 0.6 (3.9) | –0.6 to 1.9 | 0.3 | |

| Epicondylar distance | 30° | 1.2 (4.4) | –0.2 to 2.6 | 0.1 |

| 45° | 1.7 (3.6) | 0.5 to 2.8 | < 0.01 | |

| 60° | 1.7 (3.6) | 0.5 to 2.8 | < 0.01 | |

| 75° | 1.6 (3.4) | 0.5 to 2.7 | < 0.01 | |

| 90° | 0.9 (3.6) | –0.2 to 2.1 | 0.1 | |

| Rotation | 30° | –0.5 (3.5) | –1.6 to 0.6 | 0.4 |

| 45° | –0.5 (3.9) | –1.8 to 0.7 | 0.4 | |

| 60° | –1.0 (4.1) | –2.3 to 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 75° | –0.9 (4.3) | –2.3 to 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| 90° | –1.2 (4.0) | –2.5 to 0.0 | 0.1 | |

| Tilt | 30° | –1.2 (6.4) | –3.3 to 0.8 | 0.2 |

| 45° | –1.3 (5.6) | –3.2 to 0.4 | 0.1 | |

| 60° | –0.4 (4.9) | –2.0 to 1.1 | 0.6 | |

| 75° | 1.2 (4.7) | –0.2 to 2.7 | 0.1 | |

| 90° | 3.2 (4.4) | 1.8 to 4.6 | < 0.01 |

Figure 3.

Pre- and postoperative patellar kinematics (mediolateral shift: medial, +; lateral, −; axial tilt: medial, −; lateral, +; coronal rotation: external, −; internal, +; epicondylar distance (mm) during range of motion: open triangle (preoperatively) and closed circle (postoperatively)). Mean values with standard errors. Asterisks above the x-axis indicate significant differences during range of motion.

Effect of component alignment on patellar kinematics

The influence of axial and sagittal femoral and tibial component alignment (Table 2) on each patellar kinematic parameter was analyzed using generalized linear models. Due to 7 missing values and no statistically significant influence on patellar kinematics, tibial component rotation was removed from the final models. At 90° of flexion, femoral component flexion showed a significant influence on both mediolateral patellar shift and epicondylar distance. Furthermore, we found a significant influence of posterior tibial component slope on patellar epicondylar distance at 75° and 90° of flexion.

Table 2.

Intraoperative component alignment presented as means and standard deviations (external rotation: −; internal rotation: +; flexion: +; extension: −)

| n | Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rotation, femoral component | 40 | –4.0 (5.7) | –20 to 9 |

| Flexion, femoral component | 40 | 2.6 (1.9) | –2.5 to 6 |

| Posterior slope, tibial component | 40 | 4.9 (1.5) | 2 to 8 |

| Rotation, tibial component | 33 | –5.4 (9.8) | –20 to 18 |

An increase in femoral component flexion increased postoperative patellar lateral shift. The generalized linear model indicated that at 90° of flexion, a change in femoral component flexion of 1° changes the difference (preoperative-postoperative) in mediolateral patellar shift by about +0.5 mm. Both increased femoral component flexion and posterior tibial slope reduced postoperative epicondylar distance. The model indicates that at 90° of flexion, a change in femoral component flexion of 1° in combination with a change in tibial posterior slope of 1° increases the difference (preoperative-postoperative) in epicondylar distance by about 1.5 mm (0.6 mm + 0.8 mm). Therefore, the postoperative value for epicondylar distance would be reduced by about 1.5 mm. This effect is slightly reduced at flexion angles of 75° or less, according to the interaction terms with a negative sign (Table 3). In contrast to sagittal component alignment, axial femoral and tibial component alignment did not show any significant influence on patellar kinematics.

Table 3.

Influence of component alignment on the preoperative-postoperative difference in patellar kinematics estimated with generalized linear models

| ML-shift a

|

Epicondylar distance a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate b (95% CI) | p-value | Estimate b (95% CI) | p-value |

| Flexion | ||||

| 30° | 1.3 (–0.2 to 2.9) | 0.1 | 4.1 (0.4 to 7.9) | 0.02 |

| 45° | 1.1 (0.0 to 2.4) | 0.1 | 4.3 (0.9 to 7.7) | 0.01 |

| 60° | 1.0 (0.3 to 1.8) | < 0.01 | 2.4 (0.4 to 4.5) | 0.01 |

| 75° | 0.5 (0.0 to 1.1) | 0.1 | 2.5 (0.8 to 4.3) | < 0.01 |

| 90° | reference | reference | ||

| Flexion, FC (per 1°) | 0.5 (0.0 to 1.1) | 0.04 | 0.6 (0.0 to 1.2) | 0.03 |

| Flexion, FC | ||||

| Flexion a | ||||

| 30° | –0.1 (–0.5 to 0.2) | 0.5 | –0.5 (-1.0 to 0.0) | 0.1 |

| 45° | –0.1 (–0.4 to 0.2) | 0.4 | –0.3 (-0.9 to 0.1) | 0.1 |

| 60° | –0.1 (–0.3 to 0.0) | 0.2 | –0.2 (-0.5 to 0.0) | 0.1 |

| 75° | 0.0 (–0.3 to 0.2) | 0.9 | 0.0 (-0.2 to 0.1) | 0.6 |

| 90° | reference | reference | ||

| Posterior slope, TC (per 1°) | 0.4 (–0.2 to 1.1) | 0.2 | 0.9 (0.3 to 1.4) | < 0.01 |

| Posterior slope, TC | ||||

| Flexion a | not included | |||

| 30° | –0.5 (–1.1 to 0.0) | 0.1 | ||

| 45° | –0.5 (–1.1 to 0.0) | 0.1 | ||

| 60° | –0.2 (–0.5 to 0.1) | 0.2 | ||

| 75° | –0.3 (–0.6 to 0.0) | 0.04 | ||

| 90° | reference | |||

| Rotation FC (per 1°) | –0.1 (–0.3 to 0.0) | 0.2 | 0.0 (-0.1 to 0.1) | 1.0 |

Difference in preoperative and postoperative values.

The estimate of each parameter gives the change in ML-shift or epicondylar distance either per one unit change in the parameter or in relation to the reference category. For example, by changing flexion from 90° to 60°, the difference (pre-post) in the ML-shift will increase by 1.0 mm and decrease by –0.1 times the flexion of the femoral component.

FC: femoral component

TC: tibial component

Discussion

We used a commercial navigation system for in vivo evaluation of patellar tracking before and after TKA. Most importantly, we found a difference between patellar tracking in preoperative arthritic knees and knees after ligament-balanced TKA. During the motion cycle, the TKA patellae had a more lateral shift and tilted more laterally until 60°, and again more medially from 60° to 90° of flexion. Interestingly, the TKA patellae tilted significantly more medially at 90° of flexion. In 2 recent cadaveric studies also, a more lateral shift and lateral tilt could be found after TKA (Chew et al. 1997, Hsu et al. 1997). The authors ascribed this effect to the geometry of the femoral implant. Also, Heinert et al. (2011) held the different shape of the patellar groove and its position in TKAs responsible for changes in patellofemoral kinematics compared to the natural knee. The mean rotation of the patella in the preoperative arthritic knee showed an irregular motion throughout flexion compared to the TKA patella. This effect could be ascribed to the arthritic deterioration of the preoperative knee. However, we could not find any statistically significant difference regarding this kinematic parameter. In TKA, the average epicondylar distance of the patella was significantly smaller than in the preoperative knee during flexion angles of 45° to 75° (p < 0.05).

In any case, the distance between the patella and the anatomical trans-epicondylar line and therefore the anterior-posterior position relative to the femur decreased during the entire range of flexion after TKA. Moreover, we found an influence of femoral component flexion and tibial component slope on epicondylar distance in the generalized linear model. Increased femoral component flexion and also increased tibial posterior slope led to a decrease in epicondylar distance and a more posterior position of the patella in relation to the femur. As reported in the Results section, the model at 90° of flexion indicated a reduction in epicondylar distance of 1.5 mm if the femoral component flexion and the tibial posterior slope increased about 1°. In any case, an increase of 3° in both femoral component flexion and posterior tibial component slope would indicate a reduction in epicondylar distance of 4.5 mm. The influence of tibial component slope on epicondylar distance could be attributed to a more posterior shift and a distalization of the femur in relation to the tibia, and therefore a more proximally placed contact point between the patella and the femoral component. However, clinical benefit from these kinematic changes has not been proven yet. Furthermore, the effect on the quadriceps muscle force still has to be investigated. Until then, great changes in femoral flexion and tibial posterior slope should be avoided to reduce the risk of altered patellar kinematics. In addition, the reduction in epicondylar distance can probably be ascribed to the different shape of the trochlear groove of the femoral component compared to the natural knee, as described by Varadarajan et al. (2011). In any case, this may be a kinematic parameter that would explain increased patellofemoral pressure and changes in peripatellar soft tissue tension after TKA throughout flexion, as described in some recent investigations (Hefzy et al. 1992, Kulkarni et al. 2000, Steinbrück et al. 2013).

Many authors have focused on the influence of femoral and/or tibial rotational component alignment on patellar kinematics in previous cadaveric, radiological, and biomechanical investigations (Berger et al. 1998, Barrack et al. 2001, Miller et al. 2001a, Romero et al. 2003, Siston et al. 2005, Belvedere et al. 2007, Lüring et al 2007, Kessler et al. 2008, Heinert et al. 2011). Heinert et al. (2011) could not find significant changes in patellar kinematics between fixed-bearing and mobile bearing TKAs, while Figgie et al. (1989) showed an influence of tibial component rotation on patellar tracking. Ranawat (1986) reported that patellar maltracking results mainly from femoral component malalignment. Berger et al. (1998) found that combined internal rotation of the femoral and tibial component correlated directly with the severity of postoperative patellofemoral complications. However, contrary to the investigations mentioned above, we found that there was no statistically significant influence of femoral or tibial component rotation—or combined component rotation—on patellar kinematics using a generalized linear model. We ascribe this to either an intraoperative range of femoral and tibial component rotation that was too small or to the well-balanced TKAs from using a ligament-balanced technique, which perhaps tolerate more rotation of the components than has been the case in cadaveric and biomechanical studies. The restoration of the joint line and therefore patellar height was achieved in every knee after TKA had been performed and an overstuffing of the femoral component could be avoided in all cases due to the visualization using the navigation system. Thus, changes in patellar kinematics after TKA cannot be ascribed to these possibly disruptive factors.

Our investigation had some limitations. First of all, we measured patellar kinematics without muscle tone and through passive range of motion. In contrast to cadaveric or computer studies, the data were collected intraoperatively, and were not influenced by possible asymmetrical pull of the attached quadriceps tendon. Thus, the data can be used for further clinical investigations and for development of intraoperative patellar tracking navigation applications. Moreover, Masri and McCormack (1995) reported that patellar congruence angles are not influenced by quadriceps contractions. In the natural knee, reference points on the patella need to be registered after arthotomy has been performed. Thus, patellar tracking of the natural knee was measured after anatomical closure of the capsule. However, standardized marks were set, to achieve the same degree of anatomical closure for patellar tracking before and after TKA. The closure and reopening of the arthrotomy and also the motion cycle were conducted with care, due to possible deterioration of the capsule. We did not investigate flexion angles between 0° and 30°. Thus, we could not analyze a possible effect of the tibiofemoral “screw home mechanism” and its influence on axial component alignment and patellofemoral kinematics, which takes place at early flexion angles. Finally, the patella was not resurfaced for measuring, to compare patellar kinematics in the natural knee with those after TKA. This might affect patellar tracking compared to resurfaced patellae after TKA.

We expected a substantial influence of axial component rotation on patellar kinematics, since most recent investigations have attached a high degree of importance to this alignment parameter (Hefzy et al. 1992, Miller et al. 2001a, Kessler et al. 2008). However, such a great influence of sagittal component alignment on patellar kinematics was not conceivable. While some recent investigations have described the influence of sagittal component alignment on tibiofemoral kinematics (Fitz et al. 2012, Baier et al. 2014, Gromov et al. 2014), we could not find any study on its influence on patellar kinematics in the current literature. The impact of sagittal component alignment could be explained by changed parapatellar soft tissue tension and tibiofemoral contact points. We have not found any previous reports on patellar epicondylar distance, which we found to be an important kinematic parameter for evaluation of the anterior-posterior shift of the patella in relation to the femur.

In summary, since patellar kinematics change substantially after TKA and sagittal component alignment appears to have a great impact, surgeons should be aware of altering sagittal alignment until the clinical relevance has been investigated. Even if a more natural-like trochlea groove in some TKAs is used, the individual intraoperative component alignment appears to be necessary to restore individual patellar kinematics in due consideration of tibiofemoral kinematics.

Acknowledgments

No competing interests declared.

AK and HRS performed operations and were the main authors. GM set up the logistics and helped in writing the manuscript. CB and JS performed operations and revised the manuscript. ES performed operations and helped in interpreting the data. FZ carried out the statistical analysis. JG performed operations.

References

- Akagi M, Oh M, Nonaka T, Tsujimoto H, Asano T, Hamanishi C. An anteroposterior axis of the tibia for total knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2004;420:213–219. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200403000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglin C, Ho K CT, Briard J-L, de Lambilly C, Plaskos C, Nodwell E, et al. In vivo patellar kinematics during total knee arthroplasty . Comput Aided Surg. 2008;13(6):377–91. doi: 10.3109/10929080802594563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier C, Fitz W, Craiovan B, Keshmiri A, Winkler S, Springorum R, et al. Improved kinematics of total knee replacement following partially navigated modified gap-balancing technique . Int Orthop. 2014;38(2):243–9. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2140-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrack RL, Schrader T, Bertot AJ, Wolfe MW, Myers L. Component rotation and anterior knee pain after total knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2001;392:46–55. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200111000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäthis H, Shafizadeh S, Paffrath T, Simanski C, Grifka J, Lüring C. Are computer assisted total knee replacements more accurately placed? A meta-analysis of comparative studies . Orthopade. 2006;35(10):1056–65. doi: 10.1007/s00132-006-1001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvedere C, Catani F, Ensini A, Barrera J L M de la, Leardini A. Patellar tracking during total knee arthroplasty: an in vitro feasibility study . Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(8):985–93. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvedere C, Ensini A, Leardini A, Dedda V, Feliciangeli A, Cenni F, et al. Tibio-femoral and patello-femoral joint kinematics during navigated total knee arthroplasty with patellar resurfacing . Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(8):1719–27. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2825-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger RA, Crossett LS, Jacobs JJ, Rubash HE. Malrotation causing patellofemoral complications after total knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 1998;356:144–153. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199811000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew J TH, Stewart NJ, Hanssen AD, Luo Z-P, Rand JA, An K-N. Differences in patellar tracking and knee kinematics among three different total knee designs . Clin Orthop. 1997;345:87–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Eisenhart-Rothe R, Siebert M, Bringmann C, Vogl T, Englmeier K-H, Graichen H. A new in vivo technique for determination of 3D kinematics and contact areas of the patello-femoral and tibio-femoral joint . J Biomech. 2004;37(6):927–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrokhi S, Keyak JH, Powers CM. Individuals with patellofemoral pain exhibit greater patellofemoral joint stress: a finite element analysis study . Osteoarthr Cartil OARS Osteoarthr Res Soc. 2011;19(3):287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitz W, Sodha S, Reichmann W, Minas T. Does a modified gap-balancing technique result in medial-pivot knee kinematics in cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty?: a pilot study . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(1):91–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2121-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin FM, Insall JN, Scuderi GR. Accuracy of soft tissue balancing in total knee arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(8):970–3. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.6503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromov K, Korchi M, Thomsen MG, Husted H, Troelsen A. What is the optimal alignment of the tibial and femoral components in knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop. 2014;85(5):480–7. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.940573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heesterbeek PC, Keijsers NW, Wymenga A. Femoral component rotation after balanced gap total knee replacement is not a predictor for postoperative patella position . Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(7):1131–6. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefzy MS, Jackson WT, Saddemi SR, Hsieh Y-F. Effects of tibial rotations on patellar tracking and patello-femoral contact areas . J Biomed Eng. 1992;14(4):329–43. doi: 10.1016/0141-5425(92)90008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinert G, Kendoff D, Preiss S, Gehrke T, Sussmann P. Patellofemoral kinematics in mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing posterior stabilised total knee replacements: a cadaveric study . Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(6):967–72. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H-C, Luo Z-P, Rand JA, An K-N. Influence of lateral release on patellar tracking and patellofemoral contact characteristics after total knee arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 1997;12(1):74–83. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katchburian MV, Bull A MJ, Shih Y-F, Heatley FW, Amis AA. Measurement of patellar tracking: assessment and analysis of the literature . Clin Orthop. 2003;412:241–259. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000068767.86536.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler O, Patil S, Colwell CW, Jr., D’Lima DD. The effect of femoral component malrotation on patellar biomechanics . J Biomech. 2008;41(16):3332–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienapfel H, Springorum H-P, Ziegler A, Klose K-J, Georg C, Griss P. [Der Einfluss der Femur- und Tibiakomponentenrotation auf das patellofemorale Versagen beim künstlichen Kniegelenkersatz.] Orthop. 2003;32(4):312–8. doi: 10.1007/s00132-002-0441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Freeman MA, Poal-Manresa J, Asencio J, Rodriguez J. The patellofemoral joint in total knee arthroplasty: is the design of the trochlea the critical factor? . J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(4):424–9. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.4342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K-Y, Slavinsky JP, Ries MD, Blumenkrantz G, Majumdar S. Magnetic resonance imaging of in vivo kinematics after total knee arthroplasty . J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;21(2):172–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D-H, Park J-H, Song D-I, Padhy D, Jeong W-K, Han S-B. Accuracy of soft tissue balancing in TKA: comparison between navigation-assisted gap balancing and conventional measured resection . Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(3):381–7. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0983-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luring C, Perlick L, Bathis H, Tingart M, Grifka J. The effect of femoral component rotation on patellar tracking in total knee arthroplasty . Orthopedics. 2007;30(11):965–7. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20071101-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masri BA, McCormack RG. The effect of knee flexion and quadriceps contraction on the axial view of the patella . Clin J Sport Med. 1995;5(1):9–17. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MC, Berger RA, Petrella AJ, Karmas A, Rubash HE. Optimizing femoral component rotation in total knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2001a;392:38–45. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MC, Zhang AX, Petrella AJ, Berger RA, Rubash HE. The effect of component placement on knee kinetics after arthroplasty with an unconstrained prosthesis . J Orthop Res. 2001b;19(4):614–20. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcott CW, Scott RD. Femoral component rotation during total knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 1999;367:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero J, Stähelin T, Wyss T, Hofmann S. Significance of axial rotation alignment of components of knee prostheses . Orthopade. 2003;32(6):461–8. doi: 10.1007/s00132-003-0475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siston RA, Patel JJ, Goodman SB, Delp SL, Giori NJ. The variability of femoral rotational alignment in total knee arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87(10):2276–80. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrück A, Schröder C, Woiczinski M, Fottner A, Müller PE, Jansson V. Patellofemoral contact patterns before and after total knee arthroplasty: an in vitro measurement . Biomed Eng Online. 2013;12(1):58. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-12-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiehl J, Komistek R, Dennis D, Paxson R, Hoff W. Fluoroscopic analysis of kinematics after posterior-cruciate-retaining knee arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995;77:884–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadarajan KM, Rubash HE, Li G. Are current total knee arthroplasty implants designed to restore normal trochlear groove anatomy? . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(2):274–81. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]