Abstract

Background and purpose

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a leading cause of early revision after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Open debridement with exchange of tibial insert allows treatment of infection with retention of fixed components. We investigated the success rate of this procedure in the treatment of knee PJIs in a nationwide material, and determined whether the results were affected by microbiology, antibiotic treatment, or timing of debridement.

Patients and methods

145 primary TKAs revised for the first time, due to infection, with debridement and exchange of the tibial insert were identified in the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR). Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen (37%) followed by coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) (23%). Failure was defined as death before the end of antibiotic treatment, revision of major components due to infection, life-long antibiotic treatment, or chronic infection.

Results

The overall healing rate was 75%. The type of infecting pathogen did not statistically significantly affect outcome. Staphylococcal infections treated without a combination of antibiotics including rifampin had a higher failure rate than those treated with rifampin (RR = 4, 95% CI: 2–10). In the 16 cases with more than 3 weeks of symptoms before treatment, the healing rate was 62%, as compared to 77% in the other cases (p = 0.2). The few patients with a revision model of prosthesis at primary operation had a high failure rate (5 of 8).

Interpretation

Good results can be achieved by open debridement with exchange of tibial insert. It is important to use an antibiotic combination including rifampin in staphylococcal infections.

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a leading cause of early revision after knee arthroplasty (Portillo et al. 2013, Dalury et al. 2013). Debridement with exchange of modular components is a treatment option that allows retention of the prosthetic components that are fixed to bone.

The early experience on debridement of infected knee arthroplasties was summarized in 1993, and the overall success rate of treatment of 377 knees was found to be only 29% (Rand 1993). In 1998, Zimmerli et al. published results of a randomized controlled trial on the role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections. The cure rate in the group treated with a combination of ciprofloxacin and rifampin was 12/12, as compared to 7/12 in the group treated with ciprofloxacin and placebo. In the algorithms for treatment of PJI published a few years later, debridement with retention of the prosthesis was recommended in early infection where the implant was stable, the soft tissues were not damaged, and rifampin was included in the antibiotic treatment of staphylococcal infections (Zimmerli and Ochsner 2003, Zimmerli et al. 2004). The Swedish Society for Infectious Diseases adopted these recommendations in the Swedish guidelines on musculoskeletal infections published in 2004 and revised in 2008 (Swedish Society for Infectious Diseases 2008).

Still, poor results of debridement of knee PJI have been reported in several recent papers from the USA, with a failure rate of 56–64% (Azzam et al. 2010, Gardner et al. 2011, Odum et al. 2011, Fehring et al. 2013). The patient materials in these studies were, however, collected over long periods of time and no information on the antibiotic treatment given was provided. A higher cure rate (three-quarters) was reported in a Spanish study on early staphylococcal infections (in 34 knees and 18 hips) treated with debridement where all except 2 patients received a combination of antibiotics including rifampin (Vilchez et al. 2011). In a larger multicenter study on staphylococcal infections, the cure rate was 55% and the use of rifampin showed a protective effect (Lora-Tamayo et al. 2013).

It has been debated how much time may be allowed to elapse from the primary operation or appearance of infection until debridement is performed. In recent guidelines from the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), debridement with retention of the prosthesis is recommended within approximately 30 days of prosthesis implantation or less than 3 weeks of onset of infectious symptoms (Osmon et al. 2013). Furthermore, there is ongoing discussion about whether the results of debridement are affected by the bacterial species causing the infection, and an unfavorable outcome has been reported in infections caused by S. aureus ( Deirmengian et al. 2003, Choi et al. 2011).

We investigated the success rate of open debridement and exchange of tibial insert in the treatment of knee PJI in a nationwide material. We also wanted to determine the effects of timing of debridement, bacterial species, and antibiotic treatment.

Patients and methods

The study was based on prospectively collected data, stored in the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR), on primary total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) performed during the years 2000–2008. The SKAR was initiated in 1975, and it prospectively follows primary knee arthroplasties inserted in Sweden (Robertsson et al. 2014). It has been estimated to capture 97% of the primary operations (SKAR 2013). The SKAR defines a revision as a new operation in a previously resurfaced knee in which 1 or more of the components are exchanged, removed, or added. In January 2012, the database was searched for first-time revisions due to infection where only the tibial insert was exchanged. We identified 155 cases, and requests were sent to the orthopedic and microbiological departments concerned for detailed hospital records and culture reports.

We used a modified version of the definition criteria presented by the American musculoskeletal infection society to verify the diagnosis of PJI (Parvizi et al. 2011). PJI was present when there was a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis, when a pathogen was isolated by culture from at least 2 separate tissue or fluid samples obtained from the affected joint, or when there was purulence in the joint. Histological analysis has not been used to diagnose PJI in Sweden. The measurement of synovial leukocyte count and polymorphonuclear neutrophil percentage (PMN%) was not in general use during the study period, and information on C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (SR) was not consistently available. 7 cases were excluded from the original search because these criteria were not fulfilled. Of these, there were 4 cases with wound rupture where the treatment included open debridement and exchange of the tibial insert. In 3 cases, debridement and exchange was performed because of suspected infection but no purulence was found in the joint. In all these cases, the cultures were negative and antibiotic treatment was discontinued. In addition, 3 cases were excluded from the original search as additional surgery had been performed before the joint became infected (due to trauma (n = 2) or an unclear reason (n = 1)).

Included in the study were 145 infected knees in 144 patients, 82 of whom (57%) were males. A 62-year-old male patient with osteoarthritis (OA) who was simultaneously bilaterally operated had both knees infected, and in the study each knee was considered to be a separate case. The mean age at primary operation was 70 (45–91) years. The diagnosis at primary operation was OA in 123 cases, inflammatory arthritis in 16, and other diagnosis in 6 (OA secondary to fracture (n = 4), osteonecrosis (n = 1), and hemophilia (n = 1)). The primary operations were performed in 46 Swedish orthopedic departments. A standard total knee prosthesis was inserted in 142 cases, and a revision model in 6. The fixation of the primary prosthesis was with cement in 142 cases, and all the bone cement used contained gentamicin.

In 12 cases (8%), the infection was regarded to be of acute hematogenous origin, with signs of infection appearing median 6 (2–11) months after the primary operation. To be classified as an acute hematogenous infection, the knee had to be well functioning without any signs of infection before a sudden inflammatory reaction. In the remaining cases, the median time from primary operation until signs of infection appeared was 14 (2–332) days.

The operation with open debridement and exchange of tibial insert was termed the index operation. These were performed in 35 different orthopedic departments throughout Sweden, the highest number of cases treated at 1 unit being 14. In the hematogenous cases, the median time from signs of infection until index operation was 4 (1–32) days. In the remaining cases, the median time from signs of infection until index operation was 7 (0–142) days, and the median time from primary operation until index operation was 23 (2–357) days. According to the observational nature of the study, the index operations did not follow any standard protocol, but in all cases the joint was opened and the tibial insert changed. In most cases, multiple tissue biopsies were taken for culture (Kamme and Lindberg 1981) and the diagnosis was confirmed by positive tissue cultures in 107 cases, by positive culture of joint fluid in 25, and by positive wound culture in combination with purulence in the joint in 3. In 10 cases, the diagnosis was based on the finding of purulence in the joint, often in combination with other signs of infection.

In some cases, antibiotic treatment had been started before obtaining adequate cultures. S. aureus was the most common pathogen detected (Table 1). In 21% of the infections, polymicrobial flora were found with coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) being detected most frequently (Table 2). No methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was isolated. All patients received antibiotic treatment, often prescribed by an infectious disease specialist. There was variation in the antibiotics chosen, in the dose, in the dose interval, and in the duration of treatment. In infections caused by staphylococci, whether or not the antibiotic treatment included rifampin was registered. Due to the large variability in the use of antibiotics, and also changes made because of adverse effects, it was not possible to conduct more detailed studies of the antibiotic treatment.

Table 1.

Pathogens isolated

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 53 | 37 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 33a | 23 |

| Streptococci | 7 | 5 |

| Enterococci | 3 | 2 |

| Other gram-positive bacteria | 2b | 1 |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 5c | 3 |

| Anaerobic bacteria | 2d | 1 |

| Polymicrobial | 30 | 21 |

| Negative culture | 10 | 7 |

| Total | 145 | 100 |

25 methicillin-resistant (MRSE), 4 methicillin-sensitive (MSSE); 4 cases with no information on methicillin resistance.

Pneumococcus and Granulicatella adiacens.

3 Enterobacter cloacae, 1 Escherichia coli, and 1 Proteus mirabilis.

Peptostreptococcus magnus (Finegoldia magna) and Propionibacterium acnes.

Table 2.

Pathogens isolated in 30 polymicrobial infections a

| n | |

|---|---|

| Coagulase-negative staphylococcib | 17 |

| Enterococci | 14 |

| Streptococci | 12 |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 12 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 9 |

| Other gram-positive bacteria | 5 |

| Propionibacterium acnes | 1 |

| Total | 70 |

2 pathogens in 22 cases, 3 pathogens in 7, and 4 pathogens in 1.

10 methicillin-resistant (MRSE); 5 methicillin-sensitive (MSSE); 2 cases with no information on methicillin resistance.

The primary outcome variable was infection that had been healed. Failure to heal was defined as: (1) dying before the end of antibiotic treatment, (2) having revision of major components due to infection, (3) having planned life-long antimicrobial treatment with or without confirmed persistent infection, or (4) having chronic infection. All re-revisions due to infection were considered to be failures, irrespective of which pathogen was cultured at the later revision. Repeated debridement was not regarded as failure.

The follow-up was not standardized. Information on date of death was gathered from the Swedish Cause of Death Register (Statistics Sweden). Revisions performed after the index operation were searched for in the Knee Arthroplasty Register. Regarding re-revision, all cases were followed for at least 2.1 years with a mean follow-up time of 4.5 years. Not all patients with persistent or new infection are re-revised, and therefore a clinical follow-up was needed. The minimal time for clinical follow-up was set at 1 year, presuming that most relapses of infection occur within this time. 31 patients were confirmed to have failed to have their infection cured within 1 year of the index operation. For the remaining cases, the mean clinical follow-up from index operation until the latest available information on the condition of the knee, or confirmed failure, was 3.6 (0–10) years. In cases where information in the medical records was missing, the patients were questioned by telephone. Despite strenuous efforts, the clinical follow-up was less than 1 year for 12 patients, 9 of whom had died when the study was started. In Sweden, it is uncommon for a patient to go to a hospital other than the treating one. Furthermore, excluding these patients would have caused selection bias.

Statistics

Chi-square test was used to compare failure rates between subgroups, except when the expected frequency in a cell of the contingency table was ≤ 5, in which case Fisher’s exact test was used. Any p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. The cumulative revision rate was calculated using the life-table method with 1-month intervals. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained using the Wilson quadratic equation with Greenwood and Peto effective sample-size estimates (Dorey et al. 1993). In the Cox regression analysis, the difference in risk between those treated and those not treated with rifampin was calculated using the treated group as a reference. That the assumption of proportional hazards was fulfilled was assessed with estat post-estimation statistics (global test and graphically). We used IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 for chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test, and STATA 13 for other tests.

Ethics

The study was approved by the local ethics committee in Lund (entry number 2011/694).

Results

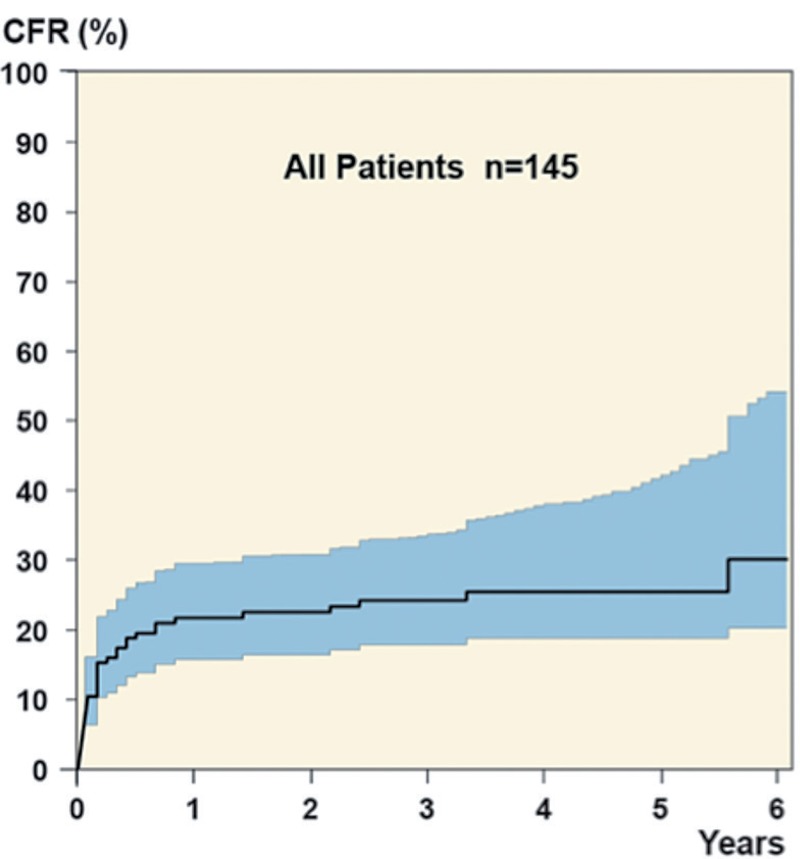

The rate of healing of PJIs was 75%. Of the 36 cases that failed, 4 patients died before the end of antibiotic treatment (6 to 160 days after the index operation), 27 underwent revision of major components due to infection, and the remaining 5 patients received life-long suppressive antibiotic treatment, only 2 of whom had a confirmed infection in the joint. Of the 27 re-revisions, there were 18 2-stage operations (3 of which failed to cure the infection), 7 arthrodeses (2 of which failed), and 2 above-the-knee amputations. In 6 cases, the infection healed after 1 additional debridement and exchange of the tibial insert and these were not regarded as failures. The median time from index revision until failure was 40 days (range: 5 days to 5 years) with 5 failures occurring more than 1 year after the index revision (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The total cumulative failure rate (CFR) up to 6 years after index operation.

Infections that were caused by S. aureus or that were polymicrobial had higher failure rates than infections caused by CNS, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 3). Of the 7 infections caused by streptococci, 2 failed to heal, and 2 of the 5 gram-negative infections failed to heal.

Table 3.

Breakdown of failure rate according to various factors

| Crude failure |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | n | Failed | rate | p-value |

| All | 145 | 36 | 25 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 83 | 19 | 23 | |

| Female | 62 | 17 | 27 | 0.5 |

| Diagnosisa | ||||

| OA | 123 | 28 | 23 | |

| Inflammatory arthritis | 16 | 4 | 25 | 0.8b |

| Other | 6 | 4 | 67 | 0.03b |

| Type of prosthesis | ||||

| Standard TKA | 137 | 31 | 23 | |

| Revision modell | 8 | 5 | 63 | 0.02b |

| Type of infection | ||||

| Hematogenous | 12 | 3 | 25 | |

| Other | 133 | 33 | 25 | 1.0b |

| Pathogenc | ||||

| S. aureus | 53 | 15 | 28 | |

| CNS | 33 | 7 | 21 | 0.5 |

| Polymicrobial | 30 | 9 | 30 | 0.9 |

| Negative culture | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0.1b |

| Use of rifampind | ||||

| Yes | 69 | 13 | 19 | |

| No | 17 | 9 | 59 | 0.01b |

| Timing | ||||

| Signs of infection ≤ 3 weekse | 126 | 29 | 23 | |

| Signs of infection > 3 weeks | 16 | 6 | 38 | 0.2b |

| Time from TKA ≤ 30 daysf | 95 | 21 | 22 | |

| Time from TKA > 30 days | 38 | 12 | 32 | 0.3 |

Comparison with OA.

Fisher’s exact test.

The most common findings presented and comparison made with S. aureus.

In monomicrobial staphylococcal infections

Information missing in 3 cases.

Hematogenous infections excluded.

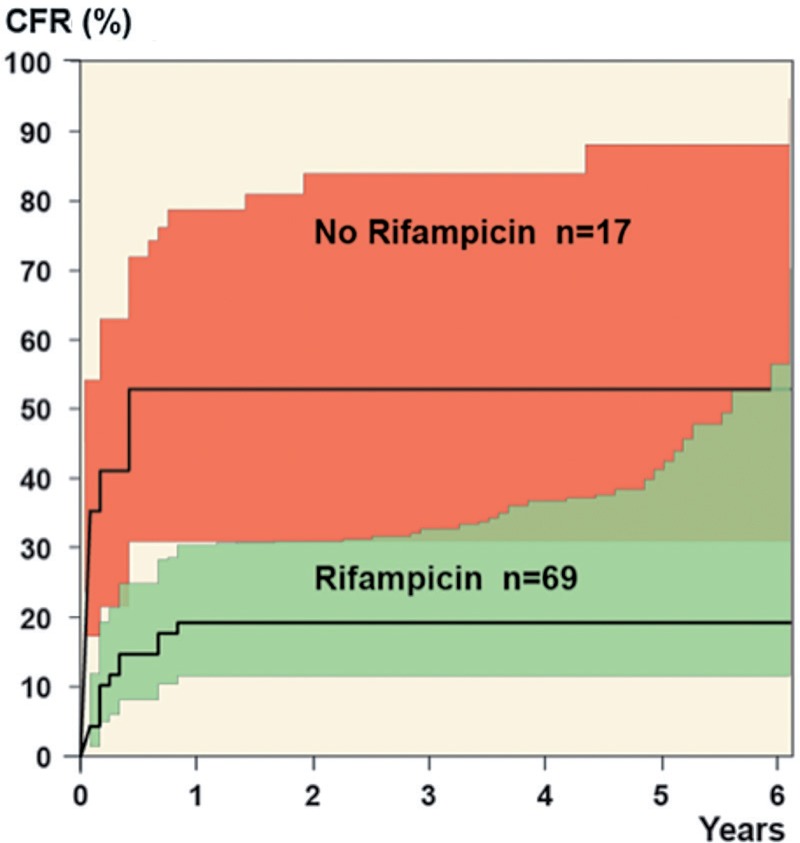

Of the 86 monomicrobial staphylococcal infections, 68 were treated with an antibiotic combination that included rifampin and the failure rate in this group was lower than in those who did not receive treatment with rifampin (p = 0.01) (Table 3). The relative risk of failure at 5 years was 4 times higher in those who did not receive rifampin (95% CI: 1.7–9.7), with most of the failures occurring within a year (Figure 2). 4 patients were re-revised within 10 days of the index operation (3 caused by S. aureus and 1 caused by CNS), and 1 patient died 6 days after index revision due to S. aureus endocarditis. These patients failed to heal before starting oral treatment, so they did not receive rifampin.

Figure 2.

The cumulative failure rate up to 6 years after index operation in staphylococcal infections, according to whether or not rifampin was used.

The failure rate was higher when the time from signs of infection until index operation exceeded 3 weeks (23% vs. 38%, p = 0.2). The number of patients who were treated after more than 3 weeks of appearance of signs of infection was only 16. The failure rate was also higher when the time from primary operation until index operation exceeded 30 days (p = 0.3) (Table 3).

There was a high failure rate in the small groups with a primary diagnosis other than osteoarthritis and inflammatory arthritis, or in patients who had a revision model inserted at the primary operation (Table 3). There was an overlap between the groups, as 3 of 6 patients with another diagnosis also had a revision model .

Mean age was similar in those whose PJI healed and in those whose PJI did not.

Discussion

Debridement and exchange of the tibial insert has been recommended as a treatment for PJI in patients who have a well-fixed prosthesis and are still within approximately 30 days of prosthesis implant or less than 3 weeks from onset of symptoms (Osmon et al. 2013). The results reported in previous studies have varied, and several factors have been suggested to affect the outcome. We investigated the results obtained with this treatment option in a nationwide material, collected throughout Sweden (with 9.5 million people).

Our study was based on data from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register, which is well established and has a clear definition of revision that is well known to Swedish orthopedic surgeons (SKAR 2013). It is, however, possible that some debridements with exchange of the tibial insert that were performed during the study period were not reported to the registry. The effect of unreported cases on the results of the study is difficult to predict, but there is no reason to believe that this would cause systematic bias. The diagnosis of infection was made by many orthopedic surgeons with varying experience of PJI, but the diagnosis was verified by our thorough reading of medical and culture reports—and even in culture-negative cases, there were clear signs of infection.

There is as yet no common definition of healed infection, which makes comparison with other studies difficult. We chose to use strict criteria, and it is possible that some of the cases that we classified as failures had actually healed. It was not possible in every case to determine whether or not death before the end of antibiotic treatment was related to the infection. Furthermore, not all patients receiving planned life-long antibiotic treatment had a verified relapse of infection, and a failure occurring a long time after the index revision might be unrelated to the first infection. On the other hand, we regarded repeated debridement as not being a failure. Some authors have regarded a second debridement as a routine procedure (Peel et al. 2013, Geurts et al. 2013), whereas others have defined failure as a return to the operating room for an infection-related problem (Fehring et al. 2013).

The follow-up was not standardized, but we have reliable information from the SKAR on re-revisions with a minimum follow-up of 2.1 years. It was a weakness of the study not to have a complete clinical follow-up of all patients for a defined period of time after finishing antibiotic treatment, but patients with no signs of infection were usually not planned for a control visit. It is unlikely that any of these patients would have been subject to treatment at any other department than the one performing the index operation. Information on potential prognostic factors, such as comorbidities, smoking, and drug abuse, could not be obtained from the registry or from the medical records. Even though our study was fairly large, there was an obvious lack of power, especially when comparing subgroups within the material.

Of the 145 knee PJIs treated with open debridement and exchange of the tibial insert, followed by antibiotics, 109 healed (75%). The 25% failure rate is lower than the 56–64% failure rate reported in several recently published studies from centers in the USA (Azzam et al. 2010, Odum et al. 2011, Fehring et al. 2013). However, neither the inclusion criteria nor the outcome variables are fully comparable. Some studies included cases of debridement without exchange of the tibial insert, which has been shown to affect the results (Choi et al. 2011). As there is no information provided in these papers on the type of antibiotic treatment, it is not possible to know if differences in choice of antibiotics could explain the variation in outcome. Our findings are in line with the success rate of 76% reported in a Spanish study (with 53 cases) on infections caused by S. aureus, where antibiotic treatment included rifampin (Vilchez et al. 2011). Higher success rates (86% and 77% after 1 and 2 years) have been reported from a specialized center in Australia, in a study (with 43 cases) on methicillin-resistant staphylococci treated with repeated debridement and antibiotics including fusidic acid and rifampin (Peel et al. 2013).

It is important to be aware of the high risk of bacteria rapidly developing resistance to rifampin, especially if the drug is used as monotherapy or before the bulk of the bacterial load has been eliminated. Several risk factors for development of resistance have been identified, and the need for extensive surgical debridement and adequate antibiotic therapy has been stressed (Achermann et al. 2013). Furthermore, drug interaction and toxicity must also be considered (Sendi and Zimmerli 2012).

We were not able to reveal any differences in failure rate depending on the infecting bacteria. However, it is notable that many of the early failures were in cases infected by S. aureus, which is well known to cause fulminant and aggressive infections. Several studies have shown that infections caused by S. aureus can lead to higher failure rates (Choi et al. 2011, Deirmengian et al. 2003, Byren et al. 2009). On the other hand, a recent Dutch study found that CNS was a risk factor for failure, but no information on the use of rifampin was provided (Kuiper et al. 2013). We noted a high failure rate (40%) in infections caused by gram-negative bacteria, but our material contained only 5 cases, so no conclusions can be drawn from the results. Interestingly, a success rate of 94% was reported in a study from Australia involving 17 cases (Aboltins et al. 2011).

We could not detect any statistically significant differences in failure rate depending on the time interval from primary operation until the debridement, as has been shown in a study on 89 PJIs treated with debridement and various local antibiotics (Geurts et al. 2013). Nor was there any difference in failure rate depending on the length of time with symptoms of infection, as found in a Spanish study on staphylococcal infections in hip and knee joints treated with debridement and levofloxacin/rifampin (Barberán et al. 2006). The number of patients who had symptoms for longer than 3 weeks before treatment was, however, small—and in the group of patients presenting with symptoms of infection a long time after the primary operation, there may have been cases of occult hematogenous infections.

5 of the 8 patients who had a revision TKA model inserted at the primary operation failed. This can be explained by a larger amount of foreign material and more extensive exposure of soft tissues.

In summary, in a series of cases treated throughout Sweden, the results of open debridement and exchange of tibial insert were satisfactory, and we recommend this treatment in early postoperative and hematogenous knee PJI. Infections caused by rifampin-sensitive staphylococci should be treated with a combination of antibiotics including rifampin.

Acknowledgments

AH, OR, and AS designed the study. The data were collected and analyzed by all authors. AH and AS prepared the manuscript, which was edited by all the authors.

We thank the personnel at the orthopedic and microbiology departments for providing us with medical records and culture reports.

References

- Aboltins C, Dowsey MM, Buising KL, et al. Gram-negative prosthetic joint infection treated with debridement, prosthesis retention and antibiotic regimens including a fluoroquinolone . Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(6):862–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achermann Y, Eigenmann K, Ledergerber B, et al. Factors associated with rifampin resistance in staphylococcal periprosthetic joint infections (PJI): a matched case-control study . Infection. 2013;41(2):431–7. doi: 10.1007/s15010-012-0325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzam KA, Seeley M, Ghanem E, Austin MS, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Irrigation and debridement in the management of prosthetic joint infection: traditional indications revisited . J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1022–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberán J, Aguilar L, Carroquino G, et al. Conservative treatment of staphylococcal prosthetic joint infections in elderly patients . Am J Med. 2006;119(11):993e7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byren I, Bejon P, Atkins BL, et al. One hundred and twelve infected arthroplasties treated with “DAIR” (debridement, antibiotics and implant retention): antibiotic duration and outcome . J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(6):1264–71. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H-R, von Knoch F, Zurakowski D, Nelson SB, Malchau H. Can implant retention be recommended for treatment of infected TKA? . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):961–9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalury DF, Pomeroy DL, Gorab RS, Adams MJ. Why are total knee arthroplasties being revised? . J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 Suppl):120–1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deirmengian C, Greenbaum J, Stern J, et al. Open debridement of acute gram-positive infections after total knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(416):129–34. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000092996.90435.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorey F, Nasser S, Amstutz H. The need for confidence intervals in the presentation of orthopaedic data . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(12):1844–52. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199312000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehring TK, Odum SM, Berend KR, et al. Failure of irrigation and débridement for early postoperative periprosthetic infection . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):250–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2373-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner J, Gioe TJ, Tatman P. Can this prosthesis be saved?: implant salvage attempts in infected primary TKA . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):970–6. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1417-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts J AP, Janssen D MC, Kessels A GH, Walenkamp G H IM. Good results in postoperative and hematogenous deep infections of 89 stable total hip and knee replacements with retention of prosthesis and local antibiotics . Acta Orthop. 2013;84(6):509–16. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.858288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamme C, Lindberg L. Aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in deep infections after total hip arthroplasty: differential diagnosis between infectious and non-infectious loosening . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981. pp. 201–7. [PubMed]

- Kuiper J WP, Vos S JC, Saouti R, et al. Prosthetic joint-associated infections treated with DAIR (debridement, antibiotics, irrigation, and retention): analysis of risk factors and local antibiotic carriers in 91 patients . Acta Orthop. 2013;84(4):380–6. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.823589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lora-Tamayo J, Murillo O, Iribarren JA, et al. REIPI Group for the Study of Prosthetic Infection. A large multicenter study of methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infections managed with implant retention . Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(2):182–94. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum SM, Fehring TK, Lombardi AV, et al. Irrigation and debridement for periprosthetic infections: does the organism matter? . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(6 Suppl):114–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America . Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(1):1–25. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Zmistowski B, Berbari EF, et al. New definition for periprosthetic joint infection: from the Workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(11):2992–4. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel TN, Buising KL, Dowsey MM, et al. Outcome of debridement and retention in prosthetic joint infections by methicillin-resistant staphylococci, with special reference to rifampin and fusidic acid combination therapy . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(1):350–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02061-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portillo ME, Salvadó M, Alier A, et al. Prosthesis failure within 2 years of implantation is highly predictive of infection . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(11):3672–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3200-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand JA. Alternatives to reimplantation for salvage of the total knee arthroplasty complicated by infection . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(2):282–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199302000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKAR (2013) Lund: The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register; 2013. Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register Report, Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J, Sundberg M, W-Dahl A, Lidgren L. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register: a review. Bone Joint Res. 2014;3(7):217–22. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.37.2000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendi P, Zimmerli W. Antimicrobial treatment concepts for orthopaedic device-related infection . Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(12):1176–84. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Society for Infectious Diseases. Vårdprogram för led-och skelettinfektioner. Revision 2008. www.infektion.net Available at.

- Vilchez F, Martínez-Pastor JC, García-Ramiro S, et al. Outcome and predictors of treatment failure in early post-surgical prosthetic joint infections due to Staphylococcus aureus treated with debridement . Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(3):439–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W, Widmer AF, Blatter M, Frei R, Ochsner P. E for the Foreign-Body Infection (FBI) Study Group. Role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections: a randomized controlled trial . JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1998;279(19):1537–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W, Ochsner PE. Management of infection associated with prosthetic joints . Infection. 2003;31(2):99–108. doi: 10.1007/s15010-002-3079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections . N Engl J Med. 2004;351(16):1645–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]