Abstract

Background

The determination of NRAS and BRAF mutation status is a major requirement in the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Mutation specific antibodies against NRASQ61R and BRAFV600E proteins could offer additional data on tumor heterogeneity. The specificity and sensitivity of NRASQ61R immunohistochemistry have recently been reported excellent. We aimed to determine the utility of immunohistochemistry using SP174 anti-NRASQ61R and VE1 anti-BRAFV600E antibodies in the theranostic mutation screening of melanomas.

Methods

142 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded melanoma samples from 79 patients were analyzed using pyrosequencing and immunohistochemistry.

Results

23 and 26 patients were concluded to have a NRAS-mutated or a BRAF-mutated melanoma respectively. The 23 NRASQ61R and 23 BRAFV600E-mutant samples with pyrosequencing were all positive in immunohistochemistry with SP174 antibody and VE1 antibody respectively, without any false negative. Proportions and intensities of staining were varied. Other NRASQ61L, NRASQ61K, BRAFV600K and BRAFV600R mutants were negative in immunohistochemistry. 6 single cases were immunostained but identified as wild-type using pyrosequencing (1 with SP174 and 5 with VE1). 4/38 patients with multiple samples presented molecular discordant data. Technical limitations are discussed to explain those discrepancies. Anyway we could not rule out real tumor heterogeneity.

Conclusions

In our study, we showed that combining immunohistochemistry analysis targeting NRASQ61R and BRAFV600E proteins with molecular analysis was a reliable theranostic tool to face challenging samples of melanoma.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13000-015-0359-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Melanoma, BRAF, NRAS, Molecular analysis, Immunohistochemistry

Background

In the last decade, an improved understanding of the genetic mutations in melanoma has resulted in a better knowledge and treatment of this malignant disease. Several mutations have been identified that might affect downstream signaling to increase cell proliferation and to decrease apoptosis [1]. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway represents a major signaling cascade driving cell proliferation, differentiation and survival. This RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway is constitutively activated in melanomas harboring mutations in oncogenes such as BRAF and NRAS, respectively mutated in about 50 % and 15 % of these tumors [2].

The development of targeted therapies such as selective BRAF inhibitors has improved the response rate, the progression-free survival and the overall survival of patients with metastatic BRAF-mutant melanomas [3–6]. The vast majority of these serine/threonine protein-kinase mutations are characterized by the substitution of valine at amino acid position 600, referred to as BRAFV600. This substitution leads to a conformational change resulting in constitutive kinase activity and phosphorylation of downstream targets. Concerning BRAFV600 mutations, about 85–90 % result in a substitution of a valine by a glutamic acid (BRAFV600E). Other less frequent mutations are: BRAFV600K (ranging from 5 to 30 %), and BRAFV600R, BRAFV600D, BRAFV600M, BRAFV600E2, BRAFV600EK601del . Other BRAF hot spots, such as BRAFL597P and BRAFL597S have incidences less than 1 %. Response to targeted-therapies concerning the most frequent and rarer mutations have been reported [7–10]. BRAF inhibitors are now the first-line treatment for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma which test is positive for BRAFV600, in accordance with the recommendations of the health authorities such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and European guidelines [11, 12].

However, targeting BRAF alone doesn’t definitively stop disease progression. Other MAPK pathway proteins such as MEK or NRAS are now the targets of new agents that are tested in a growing number of clinical trials. These new agents could increase BRAF-inhibitors’ effectiveness and hinder drug resistance [5, 13–17].

NRAS mutations, were classically reported to be nearly mutually exclusive to BRAF mutations, at least at the level of single cells, with only rare recently reported exceptions [18–22]. The main NRAS-mutations affect the glutamine at the amino-acid position 61, in 80–90 % of NRAS-mutant melanomas, with mutations encoded as NRASQ61R, NRASQ61L, and NRASQ61K. Other less frequent mutation hot spots at amino acid 12 and 13 have been described [23]. NRASQ61R appears to be the more frequent NRAS mutation in melanoma with about 40–67 % to of NRAS mutations [20, 24]. NRAS targeting is a new field in melanoma treatment and there is no consensus on the NRAS inhibitors to date [25–28]. Nevertheless, the determination of NRAS mutational status is already of interest in melanoma treatment strategies. NRAS mutations are common mechanisms of resistance during treatment with BRAF inhibitors [16, 29]. More recently, therapeutic trials reported an activity of MEK1/2 inhibitors in patients with NRAS-mutated melanoma [30]. Recent data suggested that NRAS mutation in melanoma was also a predictive factor for response to high-dose interleukin 2 indicating that immunotherapy could become the first-line treatment for NRAS-mutated metastatic melanomas, prior to MEK inhibition [31, 32].

For these reasons, the determination of BRAF and NRAS mutation status appears to be a major criterion for treatment choices. Validated molecular methods are available to analyze this status, such as pyrosequencing technology [33–36]. However, for immunohistochemistry (IHC), mainly BRAFV600E detection is yet accepted [33, 37–43]. To our knowledge, there are only two recent studies concerning anti-NRASQ61R IHC screening in the literature [19, 20]. This new antibody may provide additional information on BRAF and NRAS mutational status, especially concerning potential intratumoral genetic heterogeneity.

This context prompt us, first, to analyze, with pyrosequencing and IHC, NRASQ61R, BRAFV600E and other usual mutations, out of 142 primary and metastatic melanoma specimens from 79 patients, and to search for heterogeneity between primary tumors and metastases. Secondly, we attempted to evaluate the interest of this detection in the theranostic mutation screening of melanoma.

Methods

Case selection

We collected 142 melanoma samples from 79 patients selected from the cases analyzed at the Brest Molecular Genetic Cancer Platform (France) for theranostic purposes or archived specimens from deceased patients. In this file, some of the patients were selected because we had primary and metastatic tumoral samples and some were included because of their known BRAF and NRAS mutated status. Patients ongoing treatment with anti-BRAF target therapy were not included in our study because BRAF inhibitors can induce acquired NRAS mutations. So NRAS mutations in metastatic tumoral specimens could reflect a treatment-linked selection pressure and not true primary intra-patient tumoral heterogeneity (16;29). Cases are summarized in Table 1. The patients’ ages ranged from 17 to 90 years old (average 63.7 years old). The metastatic tumor sites were lymph nodes, skin, brain, lung, stomach, mesentery, liver and parotid gland (see Additional file 1: Table S1 for details). We analyzed both primary and metastatic formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens for the same patient, when different samples were available. Histology slides were read to confirm the diagnosis and the presence of sufficient tumor tissue for both DNA extraction and pyrosequencing and for IHC analysis. The presence and amount of melanin-pigmentation were quantified at low magnification using a semi-quantitative scoring: 0 (absence), 1+ (less than 25 % of pigmented tumor cells), 2+ (25–49 % of pigmented tumor cells), 3+ (50–74 % of pigmented cells) or 4+ (75–100 % of pigmented tumor cells). This study was approved by CHRU Brest our institutional review board (CPP n° DC – 2008 – 214).

Table 1.

Summary of the samples available concerning the 79 patients included in the study

| Both primary tumor and metastasis | 33 |

| More than one metastasis without primary melanoma | 5 |

| Only one metastasis without primary melanoma | 26 |

| Only primary melanoma | 15 |

DNA extraction

Maxwell 16 CE-IVD system (Promega corporation, Fitchburg, WI, USA) combined with the Maxwell® 16 FFPE Tissue LEV DNA Purification Kit (Promega corporation, Fitchburg, WI, USA) was used to isolate DNA from 3 series of 5 μm sections of macro-dissected tissue blocks. DNA was eluted with 100 μl of water provided by the manufacturer.

Mutation analyses

Pyrosequencing

The templates (173 bp of exon 15 of BRAF and 124 bp of exon 3 of NRAS genes) were amplified using the multiplex-PCR kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) in a 20 μl final volume containing 2 μl of the tumor DNA. The genotyping of codons 600 of BRAF and 61 of NRAS was carried out on PyroMark Q24 system (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) (see Table 2 for PCR primers sequences and parameters). Nucleotide numbering was done in accordance with HGVS recommendations (www.hgvs.org/mutnomen). The reference sequences NM_004333.4 for BRAF gene and NM_002524.4 for NRAS gene were used for cDNA-based numbering, i.e. the A of the ATG translational initiation codon was ascribed as +1. Analyses were considered as non conclusive (NC) when the pyrosequencing analysis process failed.

Table 2.

Pyrosequencing primers and parameters for genotyping the codons 600-BRAF and 61-NRAS

| Gene | PCR primers sequence (Forward and Reverse 5′ → 3′) | Pyrosequencing primer | Nucleotides dispensation order |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF | Biotin-GCTTGCTCTGATAGGAAAATG | GATGGGACCCACTCCATCGAGA | GTCTACTGT |

| CCACAAAATGGATCCAGACA | |||

| NRAS | ACACCCCCAGGATTCTTACAGA | GACATACTGGATACAGCTGGA | TCGTATCGAGAG |

| Biotin-GCCTGTCCTCATGTATTGGTC |

Next generation sequencing

DNA libraries were produced using the Ion AmpliSeq™ Cancer Hotspot Panel v2 (Life Technologies, Saint-Aubin, France) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Ten bar-coded (Ion Xpress Barcodes adapters kit, Life Technologies, Saint-Aubin, France) tumor DNAs libraries were sequenced simultaneously on a 316 chip. Sequences were analyzed through the Torrent suite v4.0 for alignment and SNP-InDels detection to produce BAM and VCF output files. The data were visualized with Alamut v.2.3 software (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France) to review ambiguous nucleotide positions.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for NRASQ61R and BRAFV600E-mutant were performed using the monoclonal antibodies N-Ras (Q61R) (clone SP174, Spring Bioscience, Pleasanton, CA, USA) and BRAF V600E (clone VE1, Spring Bioscience, Pleasanton, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1:100. Immunohistochemistry was performed on Ventana Benchmark XT® automated slide preparation system (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France) using two different revelation kits, OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France) and ultraView Universal Alkaline Phosphatase Red Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). A first line IHC was performed with ultraView® kit and a second line IHC was performed with both ultraView® and OptiView® kits for cases presenting discrepancies in IHC between samples collecting from the same patient or between results of molecular mutational status and IHC. The same protocols were applied to both NRASQ61R and BRAFV600E IHC. Briefly, IHC was performed on 4 μm thick sections of the same FFPE material used for mutational testing. A positive control (NRASQ61R mutated melanoma metastasis or BRAFV600E mutated melanoma metastasis) was included in each IHC round.

UltraView® Red detection kit was used through Ventana staining procedure included pretreatment with cell conditioner 1 (pH8) for 60 min, followed by incubation with diluted antibody at 37 °C for 32 min. Antibody incubation was followed by standard signal amplification with the Ventana amplifier kit, ultra-Wash, and counterstaining with one drop of hematoxylin for 12 min and one drop of bluing reagent for 4 min. Subsequently, slides were removed from the immunostainer, washed in water with dishwashing detergent, and mounted.

Optiview® DAB detection kit was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunostaining was interpreted by a single trained pathologist (AU). As there is no recommended scoring system for the interpretation of this immunohistochemical analysis, we have scored the intensity of cytoplasmic immunolabelling as negative, “weak positive” or “strong positive”. In addition, the percentage of immunostained tumor cells was graded according to Busam et al.’s scoring system: 0 (negative), 1+ (positive in less than 25 % of tumor cells), 2+ (25–49 % of tumor cells), 3+ (50–74 % of tumor cells) or 4+ (75–100 % of tumor cells) [38].

Results

Table 3 summarizes the tumors pyrosequencing and immunohistochemistry profile (NRASQ61 or a BRAFV600 mutation and/or a NRASQ61R or a BRAFV600E positive immunohistochemistry).

Table 3.

Immunohistochemistry characteristics of positive samples and correlation with pyrosequencing mutational status. Strong / weak describes the intensity of staining and 1+ to 4+ referrers to the percentage of stained tumor cells. WT indicates wild-type samples according to pyrosequencing data

| NRAS Q61 pyrosequencing | NRAS Q61R | Non NRAS Q61R | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IHC NRASQ61R (SP174) | Strong | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| 4+ | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 3+ | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2+ | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 (WT) |

| 1+ | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| BRAF V600 pyrosequencing | BRAF V600E | Non BRAF V600E | ||

| IHC BRAFV600E (VE1) | Strong | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| 4+ | 13 | 4 | 1 (WT) | 2 (WT) |

| 3+ | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 (WT) |

| 2+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1+ | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 (WT) |

NRAS analysis

In our study, 29.1 % of the patients (23/79) were concluded to have a NRAS-mutated melanoma (17.7 % (14/79) NRASQ61R, 5.1 % (4/79) NRASQ61Land 6.3 % (5/79) NRASQ61K). NRASQ61 mutations were detected in 29.5 % of the samples (38/129) including 23 NRASQ61R (c.182A>G) mutations (17.8 % of the samples, 60.1 % of NRASQ61 mutations), 7 NRASQ61L (c.182A>T) mutations (5.4 % of the samples, 18.4 % of NRASQ61 mutations), 8 NRASQ61K (c.181C>A) mutations (6.2 % of the samples, 21.1 % of NRASQ61 mutations).

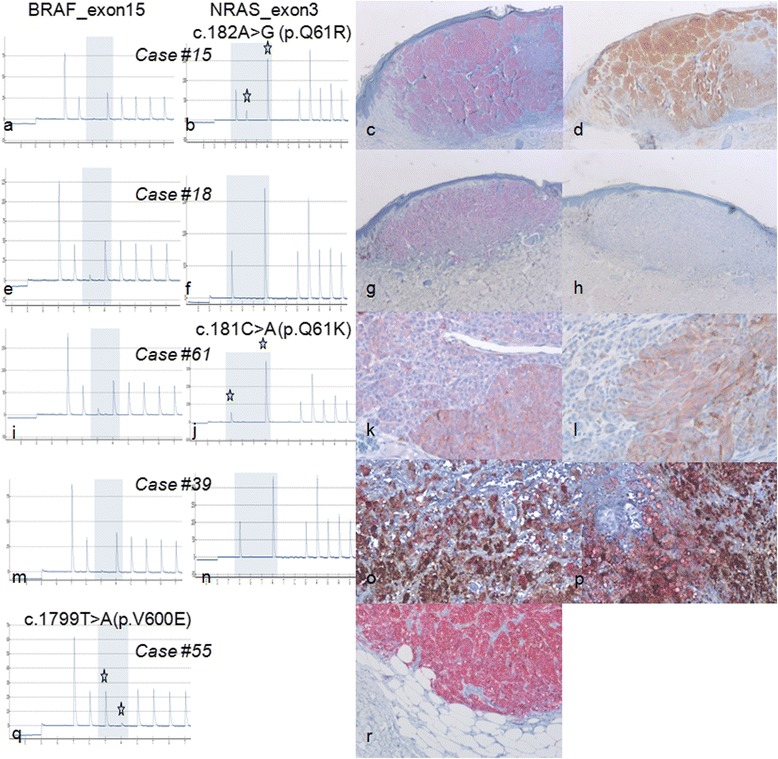

All the 23 NRASQ61R-mutant samples detected by pyrosequencing, had positive immunostaining, with the NRASQ61R SP174 antibody (from 1+ to 4+, and from weak to strong) (see Table 3 and Fig. 1a–d. There was one NRASQ61R-wild-type sample who had positive immunostaining (2+, weak). The 7 NRASQ61L-mutant and the 8 NRASQ61K-mutant detected by pyrosequencing, were negative for immunostaining, with the NRASQ61R SP174 antibody.

Fig. 1.

Examples of paired immunohistochemistry and pyrosequencing results. a, b, c, d case #15: primary BRAF V600 wild-type (a) and NRAS Q61R mutated (b) melanoma with strong 4+ immunostaining with SP 174 anti-NRASQ61R antibody using Red (c) or DAB (d) revelation. e, f, g, h case #18: primary melanoma with BRAF V600 (e) and NRAS Q61 wild-type (f) molecular status but presenting strong 4+ staining using VE1 anti-BRAFV600E antibody (g) and no staining with SP 174 anti-NRASQ61R antibody (h). i, j, k, l case #61: primary BRAF V600 wild-type (i) and NRAS Q61K mutated (j) melanoma having moderate staining using VE1 anti-BRAFV600E antibody (k) and fainter staining with SP 174 anti-NRASQ61R antibody (l). We concluded in a non-specific ambiguous staining in this sample with both antibodies. Note that red revelation kit as been used here as the faint melanin-pigmentation could simulate a weak DAB staining. m, n, o, p case #39: BRAF V600 (m) and NRAS Q61 wild-type (n) melanoma mesentery metastasis presenting both strong melanin pigment that could simulate a strong DAB staining and red immunostained cells with both VE1 anti-BRAFV600E (o) and SP 174 anti-NRASQ61R (p) antibodies. We retrospectively concluded that all stained cells were macrophages, without any evidence of viable tumor cells in this pigmented sample. q, r case #55: BRAF V600E mutated (q) melanoma skin metastasis with strong 4+ immunostaining with VE1 anti-BRAFV600E antibody (r)

Sensitivity of IHC with the NRASQ61R SP174 antibody was 100 % and the specificity was 99.1 %.

The immunostained areas with anti-NRASQ61R antibody were 4+ in 13/23 (56.5 %) of the samples including 10 samples with a strong staining intensity. 2/23 (8.7 %), which had a weak staining, with a 1+ or 2+ grade, were metastatic samples. In one sample (1/23, 4,3 %), about two thirds of the tumor surface/cells was weakly stained. The intensity of staining was strong but concerned less than 75 % of the tumor surface/cells (inferior to 4+) in 7/23 (30,4 %) of the samples.

A non-specific positive extra-tumoral staining was observed in 23/142 (16.2 %) samples in monocytes/macrophages cells (Fig. 1m–p). Within those 23 non specific cases, 7 samples had an adjacent tumor with NRASQ61R mutation and positive IHC.

BRAF analysis

In our study, 32.9 % of the patients (26/79) were concluded to have a BRAF-mutated melanoma (22.8 % (18/79) BRAFV600E, 6.3 % (5/79) BRAFV600Kand 3.7 % (3/79) BRAFV600R).

BRAFV600 mutations were found in 30.8 % (37/120) of the tested samples, including 23 BRAFV600E (c.1799T>A) mutations (19.2 % of the samples, 62.1 % of BRAFV600 mutations), 8 BRAFV600K (c.1798_1799GT>AA) mutations (6.7 % of the samples, 21.6 % of BRAFV600 mutations), 6 BRAFV600R (c.1798_1799GT>AG) mutations (5 % of the samples, 16.2 % of BRAFV600 mutations).

Immunohistochemical analysis detected immunolabelling with the anti-BRAFV600E VE1 antibody in the 23 BRAFV600E-mutant samples and in 5 BRAFV600E-wild-type samples (see Fig. 1e–h, q, r) The BRAFV600K and BRAFV600R samples showed no staining, as expected. Sensitivity of IHC detection with BRAFV600E antibody (clone VE1) was 100 % and specificity was 95.1 %.

The proportion of stained tumor cells, within the BRAFV600E-mutant samples, was graded 4+ in 17/23 (73.9 %) cases. Among these cases, the staining intensity varies from strong in 13/17 (76.4 %) to weak in 4/17 (23.5 %) (see Table 3). 2/23 BRAFV600E-mutant samples (8.7 %) and 1 BRAFV600E-wild-type sample were scored 1+ (Fig. 1i–l). A non-specific positive extra-tumoral staining of the monocytes/macrophages was observed in 52/142 (36.6 %) of the samples with the anti-BRAFV600E antibody including 7 samples with adjacent tumor with BRAFV600E mutation and positive IHC (Fig. 1m–p).

Molecular analysis technical issues and melanin pigmentation

Molecular analysis of both BRAFV600 and NRASQ61 profile was possible in 119/142 samples. Molecular testing was conclusive only for either BRAFV600 or NRASQ61 in 1/142 sample and 10/142 samples respectively. Molecular testing was not conclusive neither for BRAFV600 nor NRASQ61 in 12/142 samples. The surface of analyzed lesions ranged from a few square millimeters to a few square centimeters and there was no correlation between the volume of tumor on the slides used for DNA extraction and the molecular test results. In the samples with partially and fully conclusive molecular results, the average proportion of tumor cells was 70.8 % (from 2 to 100 %), and melanin-pigmentation was found in 38.4 % (50/130) of the cases.

Melanin-pigmentation was reported in less than 25 % of tumor cells which were 1+ (20.7 %), 25–50 % of tumor cells 2+ (7.7 %), 50–75 % of tumor cells 3+ (6.2 %) or in more than 75 % of tumor cells 4+ (3.8 %). Within the 23 samples with non-conclusive results of at least one molecular test, 9 samples showed melanin-pigmentation. However, less than 25 % of tumor cells were pigmented among 7 of these 9 samples.

Immunohistochemistry analysis technical issues and melanin pigmentation

IHC technique was repeated using the high-sensitive (ultraView Red) and the very high-sensitive (OptiView DAB) detection kits for discordant patients only. The results of these additional testings were identical to the initial results. There was no difference between Red and DAB detection systems. Melanin-pigmentation appeared in some cases to have a more grayish shade than the brown color of the DAB. However, in the samples with melanin-pigmentation it was not easy to distinguish between DAB focal cytoplasmic strong or weak staining and real melanin-pigmentation of tumor cells. Unlike DAB, phosphatase alkaline Red detection allowed easier distinction between a positive staining and melanin-pigmentation. The melanin-pigmentation was present in 7/23 (30.4 %) of NRASQ61R-mutant samples (i.e. mutated with pyrosequencing and SP174 antibody immunostaining) and in 12/23 (52.2 %) of the BRAFV600E mutant lesions (i.e. mutated with pyrosequencing and VE1 antibody immunostaining). In contrast, 36/96 (37.5 %) of the other samples showed at least focal melanin-pigmentation (1 + and higher) with melanin-pigmentation that could simulate a DAB staining.

Discrepancies between techniques and samples

For the samples showing non-conclusive molecular analysis, IHC was interpreted in all these cases. They were scored as positive with anti-NRASQ61R antibody in 1/13 (7.7 %) and with anti-BRAFV600E antibody in 3/22 (13.6 %).

Among the 38 patients with paired (primary and metastatic tumors) multiple samples, the genotype determined by pyrosequencing was discordant in 4 patients (i.e. inter-lesions): 3 for NRASQ61 (cases #39, #61, #66) and 1 for BRAFV600 (case #4). Furthermore, cases #39 and #66 had also discordant IHC using anti-NRASQ61R antibody. 2 other patients presented with a discordant result using anti-BRAFV600E IHC (cases #48, #61). For the 4 patients having discordant genotype results (cases #4, #39, #61 and #66), microsatellite markers confirmed that the samples originated from the same individual (data not shown). See Additional file 1: Table S1 for details.

Discussion

As BRAF inhibition became the reference treatment of BRAFV600-mutant metastatic melanomas, screening for BRAFV600 mutations was a major requirement for an optimal treatment with targeted therapies [44]. NRAS and BRAF mutations have been reported traditionally to be nearly mutually exclusive in a single tumor with nevertheless rare exceptions of double mutants [19–21]. As recent data suggested, new more efficient therapeutic options are becoming available in NRAS-mutated melanomas such as MEK-inhibitors and immunotherapy [26, 32]. Beside DNA based techniques, IHC with mutation-specific antibodies are emerging as a complementary theranostic tool. We evaluated the combination of novel NRASQ61R and BRAFV600E immunohistochemistry as well as pyrosequencing for mutation status profiling. In our study, mutations frequencies do not reflect frequencies encountered in the general melanoma population. Nevertheless, the numerous NRAS mutated samples included in our study offers the opportunity to focus on performances of the new SP174 anti- NRASQ61R antibody in the melanoma mutational screening.

Molecular analysis

The study by Colomba et al. only reported 1.8 % pyrosequencing analysis failure [33]. The relatively high DNA analysis failure rate (16 %; 23/142) reported in our study may be explained by the fact that many samples were archived samples, i.e. did not undergo standardized pre-analytical steps used for current samples. In our daily practice, the rate of DNA analysis failure in melanoma samples is about 3 % and about 1.5 % concerning non-melanoma samples (unpublished data). The reasons for DNA analysis failures are not always well-known. Here, we hypothesized that non-formalin fixatives, late or over-fixation may explain such failure. A high amount of melanin-pigmentation, which can play a polymerase chain reaction-inhibitor role, can explain several amplification failures but it is not a single sufficient factor as the molecular analysis of most pigmented lesions were conclusive [45].

Immunohistochemistry

IHC detection of NRASQ61R protein with SP174 antibody detected all (100 %) the NRASQ61R-mutant samples (Fig. 1a–d). Our results are consistent with those obtained by Massi et al. and Ilie et al. who have recently reported a sensitivity of 100 % and a specificity of 100 % with this novel antibody [19, 20]. This antibody showed performances similar to those published on BRAFV600E antibody [33, 37–41]. As expected, for other mutations spots/points, NRASQ61R and BRAFV600E antibodies were ineffective. These mutations represented 29/142 (20.4 %) of the samples (17/79 patients, 21.5 %) in this study.

To valid IHC screening, the staining intensity must be strong enough to be distinguished from an artifact background or melanin-pigmentation. Even if melanin-pigmentation was sometimes identified as a grayish pigmentation, the red detection was, to our experience more suitable. Chen et al. have proposed the use of mild hydrogen peroxide and heating to remove endogenous melanin in high pigmented samples to improve the reliability of using anti-BRAFV600E immunohistochemistry with DAB staining [46]. Furthermore, melanin-pigmentation was also present in monocytes/macrophages called melanophages. Distinction between a tumor cell and a melanophage was difficult, e.g. in case #39 where the pigmented macrophages could not be distinguished from DAB-detected immunostained tumor cells (Fig. 1m–p).

In our study, some lesions were regarded as difficult to analyze, along with difficulties reported in previous studies on anti- BRAFV600E IHC whatever chromogens was used [35, 37, 38, 40–43, 46, 47]. Such ambiguous staining images may explain the positive IHC scoring of BRAFV600E-wild-type samples (cases #48 and #61). The positivity of these two cases was finally considered to be an artifact background, even more in case #61 where there was also a very weak staining with anti-NRASQ61R antibody (Fig. 1i–l). Interpretation issues of NRASQ61R IHC have also recently been reported by Ilie et al. who have finally considered a faint staining as non specific and pointed out the need of a moderate to strong cytoplasmic staining of at least 60 % of tumor cells to consider this IHC as positive [19]. Massi et al. have reported a double mutant BRAFV600E and NRASQ61R strongly stained with the two anti- BRAFV600E and anti-NRASQ61R antibodies [20]. Another limitation of IHC was the interpretation of non-specific staining of monocytes/macrophages that can be interspersed or clustered, i.e. representing a focal false positive IHC scoring (Fig. 1m–o). These limitations were similar for both NRASQ61R and BRAFV600E IHC analysis. In contrast with the literature, none of our tested samples with necrosis (some metastatic samples of this study) were misidentified nor showed altered IHC results. One of the two published studies to date concerning anti-NRASQ61R antibody have also reported those issues [19].

Tumor heterogeneity or technical artifacts?

IHC of the specimens gave various intensities and percentages of tumor cells in paired primary and metastatic samples, even though they were positive with pyrosequencing. There was no difference in the staining distribution between primitive or secondary lesions. Only two cases (cases #66 and #70) seemed to have discordant primitive and secondary data. In case #66, the primary sample contained only about 2 % tumor cells and IHC using antibody targeting NRASQ61R allowed the identification of the mutated protein whereas pyrosequencing failed to identify the mutation. In the same case, an in-transit metastasis was not stained with NRASQ61R antibody and was non-conclusive for both NRASQ61 and BRAFV600 while both lymph node and skin metastasis were strongly NRASQ61R stained and mutated. In case #70, the primitive nodular melanoma was stained with BRAFV600E antibody but non-conclusive using molecular analysis and the brain metastasis were BRAFV600E stained and mutated. In this same case #70, a third lesion (a lymph node metastasis) was not stained and was non-conclusive for molecular analysis. Although we cannot rule out samples inappropriate pre-analytical features which may explain both IHC false negatives and the failure of pyrosequencing, these findings are consistent with real tumoral heterogeneity. Tumoral heterogeneity was also found in previous studies [19, 20, 38, 48–50].

Nevertheless such heterogeneity did not seem to provide a major explanation for the discrepancies among a patient’s samples. Allelic detection limits should also be taken into account for pyrosequencing false negatives.

The small proportion of tumor cells compared to non-tumor cells in some samples may be an explanation to this discrepancy as illustrated above by case #66. Moreover in case #4, in regard to BRAFV600 mutational status, the lymph node sample contained only about 10 % of tumor cells on its histopathological section and was identified as BRAFV600E-wild-type whereas other samples containing 40 and 70 % of tumor cells showed a clear identification of BRAFV600E mutation. An additional ultra-deep sequencing indeed identified 8 of 337 allelic copies (2.3 %) presenting a c.1799T>A mutation (p.V600E) in the same DNA sample used for pyrosequencing. This 2.3 % rate of mutated alleles is undoubtedly bellow pyrosequecing detection threshold. Consequently, ultra-deep sequencing can be used as an ancillary identification tool to clarify discrepancies in samples with a low density of tumor cells. A good correlation has already been described between anti-BRAFV600E IHC and ultra-deep sequencing of BRAF in colorectal carcinomas and in melanomas. Ihle et al. also reported a 3 % rate of mutated alleles in a pyrosequencing-negative but IHC BRAFV600E-positive sample [51, 52]. Mutated tumor cell sample (intended for DNA extraction) enrichment by macro- or micro-dissection guided by IHC, may improve the identification process.

Both tumor and technical features must probably be considered to explain apparent intratumoral heterogeneity in our and previous studies in contrast with others reporting strong intratumoral homogeneity [37, 53].

How to manage samples with unclear staining?

Analysis of the available literature showed that most studies report conclusive data on BRAFV600 mutation status, with only a few that reported non conclusive cases for molecular and IHC analysis [33, 37]. In the study by Boursault et al., 3 cases remained unclear in regard to VE1 anti-BRAFV600E immunostaining because of a faint equivocal brown staining in a BRAFV600E-wild-type primary melanoma, a BRAFV600E-mutant primary melanoma and a lymph node BRAFV600K-mutant metastasis [37]. Busam et al. also reported cases of 1+ weak stained BRAFV600E-mutant lesions with this antibody but regarded these cases as interpretable positive IHC cases [38]. On the contrary, Heinzerling et al. and Ihle et al. regarded a weak staining as negative [9, 51]. On 111 cases, Colomba et al. regarded 8 (7.2 %) cases as equivocal for BRAFV600E IHC because of stained macrophages, i.e. consistent with our study, and because of a nuclear staining instead of a cytoplasmic one [33]. In our study, we did not observe any isolated nuclear staining. Interpretation criteria for unclear IHC results are not known [9, 33, 37, 38, 51]. In our study, 6 NRASQ61R-mutant and 1 NRASQ61-wild-type samples were weakly stained whereas 7 BRAFV600E -mutant and 5 BRAFV600-wild-type samples also presented a weak positivity (Table 3). According to our data, caution must be exercised in case of unclear weak staining. We note that in our experience there are less numerous unclear cases with anti-NRASQ61R antibody than with anti-BRAFV600E one. Massi et al. also have reported moderate to strong cytoplasmic staining with anti-NRASQ61R antibody in all their 14 NRASQ61R-mutated samples [20]. Ilie et al. have required a moderate to strong staining in more than 60 % of tumor cells to consider the anti-NRASQ61R IHC as positive [19]. In this manner, our faintly stained- but nevertheless NRASQ61R-mutated samples above mentioned would have been scored negative in their study. This difference points out the need of homogeneous technical interpretative criteria in this field of mutation-specific IHC. To our opinion, both molecular and IHC analysis have to be taken into account to conclude in a mutated of not mutated NRAS and BRAF status in these samples.

Discrepancies between molecular and IHC analysis

Discrepancies between IHC and molecular data were also reported within a same sample. As described in our study, Massi et al. have encountered 3 discordant cases concerning 2 samples initially considered as NRASQ61R mutated but non-stained with SP-174 antibody and, at the opposite, 1 sample positive with this antibody but wild-type concerning molecular analysis. Additional molecular genetic analysis have permitted to correct this discrepancies with the final identification of two NRASQ61K mutations in the 2 negative samples with IHC, and with the identification of a NRASQ61R mutation in the IHC positive sample [20]. Ilie et al. finally have not encountered discrepant cases by considering high stringent interpretative cut off (i.e. moderate to strong staining of at least 60 % of tumor cells) and have reported a specificity of 100 % of anti-NRASQ61R IHC on the basis of pyrosequencing NRAS mutational status. The specificity of their assay was diminished to 92 % taking into account less stringent criteria (i.e. weakly stained samples corresponding to false positive as NRAS wild-type or other than NRASQ61R-mutated samples) [19].

Concerning BRAFV600E mutation, Feller et al. reported a case of a lesion being positive with IHC and negative with pyrosequencing analysis of BRAFV600E [40]. Chen et al. reported a similar case in an esophageal tumor [46]. These results concurred with those of Marin et al. for faint to moderate stained lesion [42]. Analyzing circulating melanoma cells, Hofman et al. reported 15 % of samples to be IHC positive and pyrosequencing negative [47]. Lade-Keller et al. reported on the one hand, 4/13 cases IHC positive and COBAS® system negative for BRAF mutation. These authors, on the other hand, reported a case of BRAFV600E mutated melanoma positive on COBAS® but negative on IHC [35]. Similar IHC negative and BRAFV600E mutated samples were also reported by Skorokhod et al. in 2/14 cases and by Ihle et al. who reported a double mutated codons 600 and 601 tumor, negative using IHC [43, 51]. Taking into account the molecular data as a reference, Long et al. found 35 true positives, 2 false negatives, 57 true negatives and 3 false positives using anti-BRAFV600E antibody. In Long’s study, repeated molecular analysis gave the following explanations for the false positive and negative results. One false negative was reported to be due to an initial genetic testing: false positive revealed a BRAFK601Q mutation instead of a BRAFV600E one. Three false positives were also regarded as related to genetic analysis failure. Finally 2 more BRAFV600E mutated lesions and a third lesion did not allow molecular detection of the mutation due to their lacking of enough tumor cells. Nevertheless, one BRAFV600E mutated case remained IHC negative without clear explanation [41]. Futhermore, Ihle et al. reported a case of cross reactivity with non BRAFV600E mutations with an IHC positive sample using VE1 antibody whereas molecular analysis showed a BRAFV600R mutation [51]. Heinzerling reported the same cross reactivity with a BRAFV600K mutated sample [9]. Finally, in our study, only one sample (case #18) was strongly and homogeneously (4+) stained with VE1 anti-BRAFV600E antibody but wild-type using pyrosequencing without obvious explanation to this discrepancy to date.

Which place for mutation-specific IHC?

To our opinion, the main advantage of IHC testing is the accessibility of the test that can be realized in the same time as histopathological examination. A strong positive IHC staining quick and sure for NRASQ61R or BRAFV600E antibodies can accelerate the patient’s therapeutic management. Nevertheless, conventional, longer but wider analysis using molecular techniques must be realized in case of negative or unclear IHC results. Indeed, given the performances of these IHC screenings and the need to identify all the variants of NRASQ61 and BRAFV600 to guide treatment decision, IHC cannot replace molecular analysis, an essential step in melanoma diagnosis. But IHC can be used as a first-line or a concomitant screening tool in the management of every-day sample, especially the more challenging ones, as proposed in some studies [19, 54].

Conclusions

The determination of the molecular mutated status of metastatic melanoma becomes mandatory on the best way to treat the patient. Intra- and inter-tumor molecular heterogeneity is a challenge on the avenue to a molecular diagnostic determination of melanoma. Technical artifacts must be the first explanation for such an apparent heterogeneity. As multiple primary melanomas can exist in a same patient, and as those primary malignant lesions can sometimes be totally regressive and unnoticed, precaution is required when selecting the sample to test for molecular status [53]. This is why we recommend a more exhaustive and systematic analysis of multiple-tumor specimens for patient’s care and management rather than a single molecular status [55]. As showed in our study, technical limitations concern both molecular and IHC analysis.

SP174 anti-NRASQ61R antibody seemed overall to have similar performances as VE1 anti-BRAFV600E, with only some samples remaining ambiguous. To face these challenges, we suggest a systematic combined IHC analysis of every sample, using anti-NRASQ61R and anti-BRAFV600E antibodies and molecular analysis with pyrosequencing to complete IHC. We believe that the combination of these techniques and the comparison of their results may improve the theranostic strategy of melanoma by reducing each technique’s drawbacks.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by “La Ligue contre le cancer CD29” and “Omnium group”. We would like to also acknowledge the pathologists of Brest, Lorient, Quimper, Saint-Brieuc, the Brest Hospital Biobank, and Mrs Béatrice Abiven and Miss Elodie Le Calvez for their collaboration in this study.

This study was supported by “La Ligue contre le cancer CD29” and “Omnium group”. The authors declare no other source of support concerning this work.

Additional file

Detailled features of cases and samples analyzed.

Footnotes

Cédric Le Marechal and Pascale Marcorelles contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AU conceived the study. AU, CLM, MDB and PM participated in the design of the study. AU, MT and LS carried out the immunoassays. LP and CLM carried out the molecular genetic studies. AU, MT, CLM and PM drafted the manuscript. SC, ZA and MDB helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Arnaud Uguen, Email: arnaud.uguen@chu-brest.fr.

Matthieu Talagas, Email: matthieu.talagas@chu-brest.fr.

Sebastian Costa, Email: sebastian.costa@chu-brest.fr.

Laura Samaison, Email: laura.samaison@gmail.com.

Laure Paule, Email: laure.paule@chu-brest.fr.

Zarrin Alavi, Email: zarrin.alavi@chu-brest.fr.

Marc De Braekeleer, Email: marc.debraekeleer@chu-brest.fr.

Cédric Le Marechal, Phone: + 33 229 020 150, Email: cedric.lemarechal@chu-brest.fr.

Pascale Marcorelles, Phone: + 33 298 223 349, Email: pascale.marcorelles@chu-brest.fr.

References

- 1.Busam KJ. Molecular pathology of melanocytic tumors. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013;30:362–74. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colombino M, Capone M, Lissia A, Cossu A, Rubino A, De Giorgi V, et al. BRAF/NRAS mutation frequencies among primary tumors and metastases in patients with melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2522–29. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, Gonzalez R, Kefford RF, Sosman J, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1694–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, Jouary T, Gutzmer R, Millward M, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60868-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amanuel B, Grieu F, Kular J, Millward M, Iacopetta B. Incidence of BRAF p.Val600Glu and p.Val600Lys mutations in a consecutive series of 183 metastatic melanoma patients from a high incidence region. Pathology. 2012;44:357–9. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e3283532565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahlman KB, Xia J, Hutchinson K, Ng C, Hucks D, Jia P, Atefi M, et al. BRAF(L597) mutations in melanoma are associated with sensitivity to MEK inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:791–7. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinzerling L, Kuhnapfel S, Meckbach D, Baiter M, Kaempgen E, Keikavoussi P, et al. Rare BRAF mutations in melanoma patients: implications for molecular testing in clinical practice. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2164–71. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein O, Clements A, Menzies AM, O’Toole S, Kefford RF, Long GV. BRAF inhibitor activity in V600R metastatic melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1073–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coit DG, Thompson JA, Andtbacka R, Anker CJ, Bichakjian CK, Carson WE, et al. Melanoma, version 4.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:621–9. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dummer R, Hauschild A, Guggenheim M, Keilholz U, Pentheroudakis G. Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 7):vii86–vii91. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson S, Bloom KJ, Vallera DU, Rueschoff J, Meldrum C, Schilling R, et al. Multisite analytic performance studies of a real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of BRAF V600E mutations in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens of malignant melanoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1385–91. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2011-0505-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flaherty KT. Dividing and conquering: controlling advanced melanoma by targeting oncogene-defined subsets. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;29:841–6. doi: 10.1007/s10585-012-9488-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johannessen CM, Boehm JS, Kim SY, Thomas SR, Wardwell L, Johnson LA, et al. COT drives resistance to RAF inhibition through MAP kinase pathway reactivation. Nature. 2010;468:968–72. doi: 10.1038/nature09627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nazarian R, Shi H, Wang Q, Kong X, Koya RC, Lee H, et al. Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature. 2010;468:973–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagle N, Emery C, Berger MF, Davis MJ, Sawyer A, Pochanard P, et al. Dissecting therapeutic resistance to RAF inhibition in melanoma by tumor genomic profiling. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3085–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edlundh-Rose E, Egyhazi S, Omholt K, Mansson-Brahme E, Platz A, Hansson J, Lundeberg J. NRAS and BRAF mutations in melanoma tumours in relation to clinical characteristics: a study based on mutation screening by pyrosequencing. Melanoma Res. 2006;16:471–8. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000232300.22032.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilie M, Long-Mira E, Funck-Brentano E, Lassalle S, Butori C, Lespinet-Fabre V, et al. Immunohistochemistry as a potential tool for routine detection of the NRAS Q61R mutation in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:786–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massi D, Simi L, Sensi E, Baroni G, Xue G, Scatena C, et al. Immunohistochemistry is highly sensitive and specific for the detection of NRASQ61R mutation in melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:487–97. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollock PM, Harper UL, Hansen KS, Yudt LM, Stark M, Robbins CM, et al. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat Genet. 2003;33:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sensi M, Nicolini G, Petti C, Bersani I, Lozupone F, Molla A, et al. Mutually exclusive NRASQ61R and BRAFV600E mutations at the single-cell level in the same human melanoma. Oncogene. 2006;25:3357–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bucheit AD, Syklawer E, Jakob JA, Bassett RL, Jr, Curry JL, Gershenwald JE, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes with specific BRAF and NRAS mutations in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 2013;119:3821–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakob JA, Bassett RL, Jr, Ng CS, Curry JL, Joseph RW, Alvarado GC, et al. NRAS mutation status is an independent prognostic factor in metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 2012;118:4014–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fedorenko IV, Gibney GT, Smalley KS. NRAS mutant melanoma: biological behavior and future strategies for therapeutic management. Oncogene. 2013;32:3009–18. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibney GT, Weber JS. Expanding targeted therapy to NRAS-mutated melanoma. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:186–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwong LN, Costello JC, Liu H, Jiang S, Helms TL, Langsdorf AE, et al. Oncogenic NRAS signaling differentially regulates survival and proliferation in melanoma. Nat Med. 2012;18:1503–10. doi: 10.1038/nm.2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Posch C, Ortiz-Urda S. NRAS mutant melanoma–undrugable? Oncotarget. 2013;4:494–5. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McArthur GA, Ribas A, Chapman PB, Flaherty KT, Kim KB, Puzanov I, et al. Molecular analyses from a phase I trial of vemurafenib to study mechanism of action (MOA) and resistance in repeated biopsies from BRAF mutation positive metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;31(Suppl):3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ascierto PA, Schadendorf D, Berking C, Agarwala SS, van Herpen CM, Queirolo P, et al. MEK162 for patients with advanced melanoma harbouring NRAS or Val600 BRAF mutations: a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:249–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson DB, Lovly CM, Flavin M, Ayers GD, Zhao Z, Iams W, et al. NRAS mutation: a potential biomarker of clinical response to immune-based therapies in metastatic melanoma (MM) J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(Suppl):abstract 9019. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joseph RW, Sullivan RJ, Harrell R, Stemke-Hale K, Panka D, Manoukian G, et al. Correlation of NRAS mutations with clinical response to high-dose IL-2 in patients with advanced melanoma. J Immunother. 2012;35(1):66–72. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182372636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colomba E, Helias-Rodzewicz Z, von Deimling A, Marin C, Terrones N, Pechaud D, et al. Detection of BRAF p.V600E mutations in melanomas: comparison of four methods argues for sequential use of immunohistochemistry and pyrosequencing. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Curry JL, Torres-Cabala CA, Tetzlaff MT, Bowman C, Prieto VG. Molecular platforms utilized to detect BRAF V600E mutation in melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2012;3:267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lade-Keller J, Romer KM, Guldberg P, Riber-Hansen R, Hansen LL, Steiniche T, et al. Evaluation of BRAF mutation testing methodologies in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cutaneous melanomas. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan YH, Liu Y, Eu KW, Ang PW, Li WQ, Salto-Tellez M, et al. Detection of BRAF V600E mutation by pyrosequencing. Pathology. 2008;40:295–8. doi: 10.1080/00313020801911512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boursault L, Haddad V, Vergier B, Cappellen D, Verdon S, Bellocq JP, et al. Tumor homogeneity between primary and metastatic sites for BRAF status in metastatic melanoma determined by immunohistochemical and molecular testing. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Busam KJ, Hedvat C, Pulitzer M, von Deimling A, Jungbluth AA. Immunohistochemical analysis of BRAF(V600E) expression of primary and metastatic melanoma and comparison with mutation status and melanocyte differentiation antigens of metastatic lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:413–20. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318271249e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Capper D, Preusser M, Habel A, Sahm F, Ackermann U, Schindler G, et al. Assessment of BRAF V600E mutation status by immunohistochemistry with a mutation-specific monoclonal antibody. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:11–9. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0841-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feller JK, Yang S, Mahalingam M. Immunohistochemistry with a mutation-specific monoclonal antibody as a screening tool for the BRAFV600E mutational status in primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:414–20. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Long GV, Wilmott JS, Capper D, Preusser M, Zhang YE, Thompson JF, et al. Immunohistochemistry is highly sensitive and specific for the detection of V600E BRAF mutation in melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:61–5. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826485c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marin C, Beauchet A, Capper D, Zimmermann U, Julie C, Ilie M, et al. Detection of BRAF p.V600E mutations in melanoma by immunohistochemistry has a good interobserver reproducibility. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:71–5. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0031-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skorokhod A, Capper D, von Deimling A, Enk A, Helmbold P. Detection of BRAF V600E mutations in skin metastases of malignant melanoma by monoclonal antibody VE1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:488–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, Brandhuber BJ, Anderson DJ, Alvarado R, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eckhart L, Bach J, Ban J, Tschachler E. Melanin binds reversibly to thermostable DNA polymerase and inhibits its activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;271:726–30. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Q, Xia C, Deng Y, Wang M, Luo P, Wu C, et al. Immunohistochemistry as a quick screening method for clinical detection of BRAF(V600E) mutation in melanoma patients. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:5727–33. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1759-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hofman V, Ilie M, Long-Mira E, Giacchero D, Butori C, Dadone B, et al. Usefulness of immunocytochemistry for the detection of the BRAF(V600E) mutation in circulating tumor cells from metastatic melanoma patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1378–81. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin J, Goto Y, Murata H, Sakaizawa K, Uchiyama A, Saida T, Takata M. Polyclonality of BRAF mutations in primary melanoma and the selection of mutant alleles during progression. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:464–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilmott JS, Menzies AM, Haydu LE, Capper D, Preusser M, Zhang YE, et al. BRAF(V600E) protein expression and outcome from BRAF inhibitor treatment in BRAF(V600E) metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:924–31. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yancovitz M, Litterman A, Yoon J, Ng E, Shapiro RL, Berman RS, et al. Intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity of BRAF(V600E))mutations in primary and metastatic melanoma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ihle MA, Fassunke J, Konig K, Grunewald I, SchlaaK M, Kreuzberg N, et al. Comparison of high resolution melting analysis, pyrosequencing, next generation sequencing and immunohistochemistry to conventional Sanger sequencing for the detection of p.V600E and non-p.V600E BRAF mutations. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rossle M, Sigg M, Ruschoff JH, Wild PJ, Moch H, Weber A, Rechsteiner MP. Ultra-deep sequencing confirms immunohistochemistry as a highly sensitive and specific method for detecting BRAF mutations in colorectal carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:623–31. doi: 10.1007/s00428-013-1492-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Menzies AM, Lum T, Wilmott JS, Hyman J, Kefford RF, Thompson JF, et al. Intrapatient homogeneity of BRAFV600E expression in melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:377–82. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fisher KE, Cohen C, Siddiqui MT, Palma JF, Lipford EH, III, Longshore JW. Accurate detection of BRAF p.V600E mutations in challenging melanoma specimens requires stringent immunohistochemistry scoring criteria or sensitive molecular assays. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:2281–93. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richtig E, Schrama D, Ugurel S, Fried I, Niederkorn A, Massone C, Becker JC. BRAF mutation analysis of only one metastatic lesion can restrict the treatment of melanoma: a case report. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:428–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]