Abstract

Background

Diagnosis of dementia often requires specialist referral and detailed, time-consuming assessments.

Aim

To investigate the utility of simple clinical items that non-specialist clinicians could use, in addition to routine practice, to diagnose all-cause dementia syndrome.

Design and setting

Cross-sectional diagnostic test accuracy study. Participants were identified from the electoral roll and general practice lists in Caerphilly and adjoining villages in South Wales, UK.

Method

Participants (1225 men aged 45–59 years) were screened for cognitive impairment using the Cambridge Cognitive Examination, CAMCOG, at phase 5 of the Caerphilly Prospective Study (CaPS). Index tests were a standardised clinical evaluation, neurological examination, and individual items on the Informant Questionnaire for Cognitive Disorders in the Elderly (IQCODE).

Results

Two-hundred and five men who screened positive (68%) and 45 (4.8%) who screened negative were seen, with 59 diagnosed with dementia. The model comprising problems with personal finance and planning had an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.86 to 0.97), positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 23.7 (95% CI = 5.88 to 95.6), negative likelihood ratio (LR−) of 0.41 (95% CI = 0.27 to 0.62). The best single item for ruling out was no problems learning to use new gadgets (LR− of 0.22, 95% CI = 0.11 to 0.43).

Conclusion

This study found that three simple questions have high utility for diagnosing dementia in men who are cognitively screened. If confirmed, this could lead to less burdensome assessment where clinical assessment suggests possible dementia.

Keywords: cohort studies, dementia, diagnostic tests, general practice, sensitivity and specificity

INTRODUCTION

The diagnostic pathway for dementia, particularly in the UK, is changing. Case-finding seeks to identify people with possible dementia who have not been formally diagnosed, and has been a source of particular debate.1–4 In contrast, a formal diagnosis aims to be as definitive as possible about the presence or absence of dementia, but the process of getting a diagnosis is often not patient-centred.5 In the general population there are often multiple contributing pathologies to dementia syndrome,6,7 with the association between Alzheimer’s pathology and dementia weakening with age.8 Recent innovations in UK clinical practice have expanded the role of primary care in the diagnosis of dementia, such as GPs diagnosing patients without referral,9 or arranging for a specialist to visit primary care.10 In the UK, GPs are being encouraged to diagnose dementia independently,11 at least in people with moderately advanced disease.12

Few studies exist to provide an evidence-based approach to the diagnosis of dementia by GPs. The World Health Organization recommends that dementia is diagnosed by non-specialists in routine cases in low and middle income countries13; indeed the global clinical judgement of repeated GP consultations (three or four 10-minute-consultations) has moderate utility for the diagnosis of dementia with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.74.14 An AUC of 0.5 indicates a test no better than chance, such as coin-tossing, whereas an AUC of 1 indicates no diagnostic errors. In community-dwelling older people, a combination of functional activities questionnaire score15 with Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score16 and age had an AUC of 0.95.17 However, the MMSE is relatively time-consuming (between 7 and 18 minutes)18 and copyright-protected. GPs commonly report lack of time as a barrier to diagnosing dementia.19 It is desirable to identify the utility of simple clinical items that could be used easily by clinicians, as has been shown for the diagnosis of major depression in which two simple items have an AUC of 0.93.20

The present study used data from the Caerphilly Prospective Study (CaPS) to examine the utility of a variety of simple questions around everyday function, as well as conventional clinical assessment, for diagnosing dementia in older men. It aimed at identifying a quick and simple combination of questions that could be used by a GP as a further diagnostic test, in a person whom they suspected of having dementia after the usual clinical evaluation.

METHOD

Participants

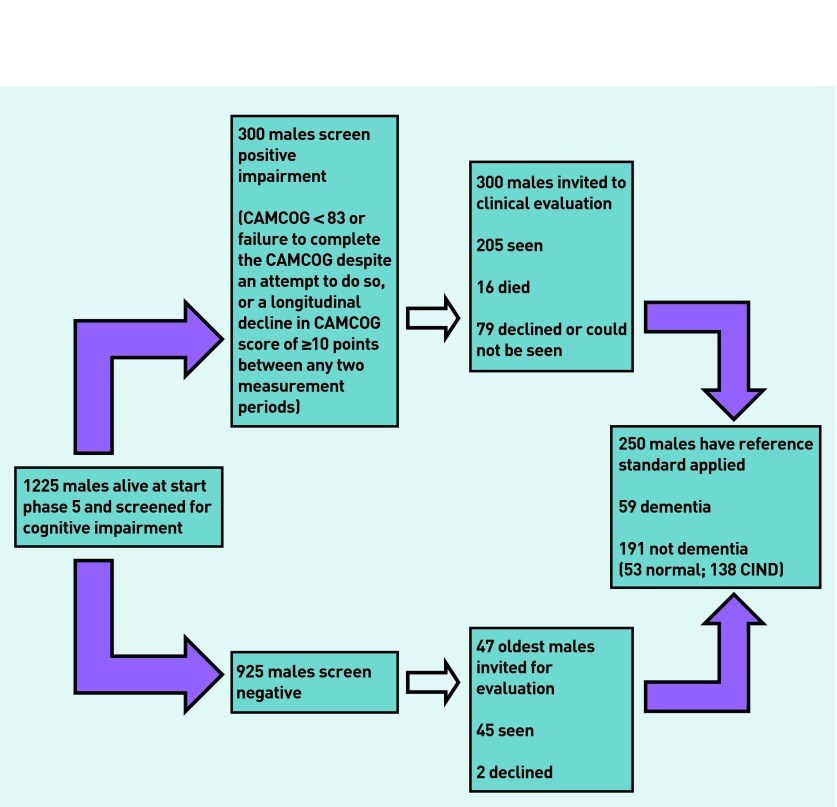

CaPS is a cohort study of men that was established to investigate cardiovascular disease.21 Men aged 45–59 years were identified from the electoral roll and general practice lists in Caerphilly and adjoining villages in South Wales, UK. Initial participation rate was 89% and 2512 men were examined in phase 1 (July 1979 to September 1983) and then followed-up at regular intervals. Cognition was assessed at phases 3 (November 1989 to September 1993), 4 (October 1993 to February 1997), and 5 (September 2002 to June 2004) using tests including the MMSE.16 At phase 5 all men who met screening criteria,22 as well as a sample of those who screened negative, were invited for a clinical evaluation in their home or research clinic by a neurologist. Figure 1 shows the selection of participants and provides the screening criteria.

Figure 1.

Flow of participation in the study.

How this fits in

Commissioners are interested in expanding the role of primary care in diagnosing some people with dementia without referral. However, GPs report lack of time as a barrier to this. The present study identifies three simple questions about functioning that had greater specificity than the composite MMSE (Mini Mental State Examination) for diagnosing dementia. These can be used easily by GPs as part of their assessment of a patient whom they believe may have a diagnosis of dementia.

Index test and reference standard

The reference standard was a consensus diagnosis of dementia made by two clinicians with specialist training in memory disorders using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),23 after reviewing all relevant information including medical records (including investigations where available) and the clinical assessment.22

The index tests were items from the clinical assessment, incorporating a structured history and neurological examination (Cardiff modified CAMDEX24 and Frontal Assessment Battery25) and an informant interview (IQCODE26). Clinical assessment was conducted without prior knowledge of the patient and the informant questionnaire was conducted at the end of the evaluation. Individual items evaluated physical functioning (for example, incontinence), symptom patterns (for example, variability), personality (for example, aggression), and social functioning (for example, ability to plan), and were assessed either directly by the clinician or from the participant and informant (see Appendix 1 for detailed list of items).

Statistical methods

The diagnostic utility of each index item was assessed by calculating standard diagnostic measures, positive and negative predictive values (PPV, NPV), sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratio (LR+, LR−), diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), and AUC with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). As a result of small cell counts, any variable that had more than two categories (for example, normal versus abnormal) was dichotomised. Equivocal physical examination findings were analysed initially as present.

As it was desired to combine index items, only items that met conventional statistical significance (P<0.05) were modelled, and where there were at least 20 subjects in each cell so diagnostic but infrequent items (for example, pout reflex) were excluded. Logistic regression models were used with dementia as the outcome and the index items as diagnostic predictors.27 First, backward stepwise logistic regression models were used with all items meeting the above criteria. Second, this was repeated but using only the five items with the greatest DOR and backwards and forwards stepwise models were run. This was also repeated using the Youden Index,28 as standard stepwise approaches maximise the AUC but not necessarily the diagnostic utility.28

For each model, the model probability of dementia was examined, and only models in which the highest risk was at least 90% were selected, then goodness of fit statistics were calculated to choose between these models.29

In addition the following supplementary analyses were made: any subjects with a prior diagnosis of dementia were excluded; analyses were repeated but recoding equivocal clinical items as absent; imputation was used for missing item data using chained equations and creating seven simulated datasets.30 All analyses were conducted in Stata (version 13).

RESULTS

At the start of phase 5, 1225 men were alive and 300 were screen positive. Of those who were screen positive 205 (68%) attended clinical assessment. In addition, 47 of the 925 men who screened negative were invited for clinical assessment,22 with 45 (95.7%) of these subsequently assessed (see Figure 1 for details for non-response). Seven had already been given a diagnosis of dementia. The cognitive screening procedures were 98% sensitive for identifying men with dementia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cross-tabulation of cognitive impairment screen against reference standard

| Dementia (DSM-IV) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Yes | No | Total | |||

| Cognitive impairment screena | Positive | 58 | 147 | 205 | |

| Negative | 1 | 44 | 45 | ||

| Total | 59 | 191 | 250 | ||

Cambridge Cognitive Examination (CAMCOG) <83 or failure to complete the CAMCOG despite an attempt to do so, or a longitudinal decline in CAMCOG score of ≥ 10 points between any two measurement periods.

Fifty-nine men (24%; 95% CI = 19% to 29%) were diagnosed as having dementia (median age 77.8 years; interquartile range [IQR] 74.9–80.0) and 191 (76%; 95% CI = 71% to 81%) did not have dementia (median age 75.7 years; IQR 71.8–79.3). The median (IQR) MMSE score in men with dementia was 20 (16–23) compared with 25 (22–29) in those without dementia. One-hundred and thirty-eight men were identified as having cognitive impairment not dementia (CIND), and they were included in the no-dementia group for analysis.

Table 2 presents the sensitivity and specificity for the individual clinical items that were examined in combinations. The most sensitive items were participant report of any memory difficulty (91.1%; 95% CI = 80.4% to 97.0%) or forgetting where things were left (91.1%, 95% CI = 80.4% to 97.0%), but specificity was only 19.8% and 31.9%, respectively. Highly specific items were: informant report of problems with reasoning (95.1%; 95% CI = 90.6% to 97.9%); hygiene (95.3%; 95% CI = 90.9% to 98.0%); and disinhibited behaviour (94.7%; 95% CI = 89.9% to 97.7%). A list of diagnostic utility of all single items, regardless of cell counts, is available from the authors on request; the diagnostic accuracy for some items could not be calculated because they were not identified in any men (details in Appendix 1).

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity for most useful individual clinical items

| Number with data (% missing) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| No dementia (n= 191) | Dementia (n= 59) | |||

| Any memory difficulty (subject) | 187 (0.02) | 56 (0.05) | 91.1 (80.4 to 97.0) | 19.8 (14.3 to 26.2) |

| Any memory difficulty (informant) | 157 (0.18) | 53 (0.10) | 83.0 (70.2 to 91.9) | 31.2 (24.1 to 39.1) |

| Forget where left things (subject) | 188 (0.02) | 56 (0.05) | 91.1 (80.4 to 97.0) | 31.9 (25.3 to 39.1) |

| Forget where left things (informant) | 159 (0.17) | 53 (0.10) | 81.1 (68.0 to 90.6) | 40.9 (33.2 to 49.0) |

| Forget what going to do (informant) | 148 (0.23) | 51 (0.14) | 66.7 (52.1 to 79.2) | 56.8 (48.4 to 64.9) |

| Forget names (subject) | 189 (0.01) | 56 (0.05) | 62.5 (48.6 to 75.1) | 66.7 (59.5 to 73.3) |

| Forget names (informant) | 161 (0.16) | 53 (0.10) | 62.3 (47.9 to 75.2) | 65.2 (57.3 to 72.5) |

| Repeat question (subject) | 186 (0.03) | 55 (0.07) | 65.5 (51.4 to 77.8) | 63.3 (56.0 to 70.2) |

| Repeat question (informant) | 159 (0.17) | 53 (0.10) | 66.0 (51.7 to 78.5) | 63.5 (55.5 to 71.0) |

| Wrong word (subject) | 189 (0.01) | 56 (0.05) | 51.8 (38.0 to 65.3) | 68.3 (61.1 to 74.8) |

| Wrong word (informant) | 161 (0.16) | 53 (0.10) | 50.9 (36.8 to 64.9) | 70.8 (63.1 to 77.7) |

|

| ||||

| Examination findings | ||||

| Any gait disturbance | 184 (0.04) | 56 (0.05) | 42.9 (29.7 to 56.8) | 91.3 (86.3 to 95.0) |

| Any primitive reflexes | 166 (0.13) | 46 (0.22) | 45.7 (30.9 to 61.0) | 77.1 (70.0 to 83.3) |

| Pout | 183 (0.04) | 51 (0.14) | 21.6 (11.3 to 35.3) | 93.4 (88.8 to 96.6) |

|

| ||||

| IQCODE (informant). Compared with 10 years ago, how is this person at: | ||||

| Family and friends | 133 (0.30) | 44 (0.25) | 75.0 (59.7 to 86.8) | 70.7 (62.2 to 78.3) |

| Recall recent events | 163 (0.15) | 54 (0.08) | 79.6 (66.5 to 89.4) | 65.6 (57.8 to 72.9) |

| Recall conversations | 164 (0.14) | 55 (0.07) | 78.2 (65.0 to 88.2) | 53.7 (45.7 to 61.5) |

| Recall own address | 161 (0.16) | 52 (0.12) | 50.0 (35.8 to 64.2) | 91.3 (85.8 to 95.2) |

| Recall day | 162 (0.15) | 55 (0.07) | 69.1 (55.2 to 80.9) | 78.4 (71.3 to 84.5) |

| Recall where kept | 159 (0.17) | 52 (0.12) | 73.1 (59.0 to 84.4) | 77.4 (70.1 to 83.6) |

| Recall different place | 161 (0.16) | 51 (0.14) | 86.3 (73.7 to 94.3) | 50.9 (42.9 to 58.9) |

| Work appliances | 156 (0.18) | 49 (0.17) | 53.1 (38.3 to 67.5) | 91.0 (85.4 to 95.0) |

| Learn new gadget | 157 (0.18) | 52 (0.12) | 86.5 (74.2 to 94.4) | 62.4 (54.4 to 70.0) |

| Learn in general | 162 (0.15) | 55 (0.07) | 81.8 (69.1 to 90.9) | 68.5 (60.8 to 75.6) |

| Follow story | 159 (0.17) | 52 (0.12) | 65.4 (50.9 to 78.0) | 79.3 (72.1 to 85.3) |

| Decisions | 157 (0.18) | 48 (0.19) | 60.4 (45.3 to 74.2) | 89.2 (83.2 to 93.6) |

| Shopping money | 156 (0.18) | 48 (0.19) | 50.0 (35.2 to 64.8) | 94.2 (89.3 to 97.3) |

| Personal finance | 135 (0.29) | 42 (0.29) | 66.7 (50.5 to 80.4) | 93.3 (87.7 to 96.9) |

| Everyday maths | 130 (0.32) | 43 (0.27) | 65.1 (49.1 to 79.0) | 90.8 (84.4 to 95.1) |

| Reasoning | 164 (0.14) | 55 (0.07) | 50.9 (37.1 to 64.7) | 95.1 (90.6 to 97.9) |

|

| ||||

| Everyday activities (asked of subject and informant, present if either identified) | ||||

| Any problems with daily activities | 184 (0.04) | 55 (0.07) | 54.6 (40.6 to 68.0) | 75.5 (68.7 to 81.6) |

| Dressing | 172 (0.10) | 54 (0.08) | 31.5 (19.5 to 45.6) | 90.1 (84.7 to 94.1) |

| Toileting | 172 (0.10) | 55 (0.07) | 29.1 (17.6 to 42.9) | 91.9 (86.7 to 95.5) |

| Hygiene | 170 (0.11) | 55 (0.07) | 32.7 (20.7 to 46.7) | 95.3 (90.9 to 98.0) |

|

| ||||

| Physical symptoms (informant) | ||||

| Any physical symptoms | 181 (0.05) | 52 (0.12) | 63.5 (49.0 to 76.4) | 75.7 (68.8 to 81.8) |

| Urinary incontinence | 184 (0.04) | 55 (0.07) | 47.3 (33.7 to 61.2) | 92.9 (88.2 to 96.2) |

| Falls | 186 (0.03) | 55 (0.07) | 49.1 (35.4 to 62.9) | 79.6 (73.1 to 85.1) |

|

| ||||

| General functioning report (informant) | ||||

| Often muddled | 104 (0.46) | 49 (0.17) | 53.1 (38.3 to 67.5) | 94.2 (87.9 to 97.9) |

| Sometimes muddled | 102 (0.47) | 50 (0.15) | 66.0 (51.2 to 78.8) | 78.4 (69.2 to 86.0) |

| Planning | 103 (0.46) | 46 (0.22) | 76.1 (61.2 to 87.4) | 82.5 (73.8 to 89.3) |

| Concentrating | 103 (0.46) | 47 (0.20) | 80.9 (66.7 to 90.9) | 57.3 (47.2 to 67.0) |

| Talk less | 103 (0.46) | 49 (0.17) | 55.1 (40.2 to 69.3) | 78.6 (69.5 to 86.1) |

| Repeat words | 102 (0.47) | 50 (0.15) | 48.0 (33.7 to 62.6) | 81.4 (72.5 to 88.4) |

| No insight | 101 (0.47) | 47 (0.20) | 61.7 (46.4 to 75.5) | 82.2 (73.3 to 89.1) |

|

| ||||

| Personality/emotion/behaviour (informant) | ||||

| Any personality change | 164 (0.14) | 52 (0.12) | 71.2 (56.9 to 82.9) | 56.7 (48.8 to 64.4) |

| Labile | 155 (0.19) | 50 (0.15) | 42.0 (28.2 to 56.8) | 87.1 (80.8 to 91.9) |

| Unmotivated | 152 (0.20) | 48 (0.19) | 37.5 (24.0 to 52.7) | 83.6 (76.7 to 89.1) |

| Disinhibited | 152 (0.20) | 48 (0.19) | 27.1 (15.3 to 41.9) | 94.7 (89.9 to 97.7) |

| Sleep disturbed | 152 (0.20) | 48 (0.19) | 45.8 (31.4 to 60.8) | 79.0 (71.6 to 85.1) |

| Aggressive | 153 (0.20) | 49 (0.17) | 40.8 (27.0 to 55.8) | 89.5 (83.6 to 93.9) |

| Narrowed preoccupations | 152 (0.20) | 48 (0.19) | 37.5 (24.0 to 52.7) | 92.8 (87.4 to 96.3) |

| Mental rigidity | 145 (0.24) | 49 (0.17) | 24.5 (13.3 to 38.9) | 92.4 (86.8 to 96.2) |

| Any functioning problems | 164 (0.14) | 53 (0.10) | 88.7 (77.0 to 95.7) | 40.2 (32.7 to 48.2) |

| Symptom fluctuation (any) | 146 (0.24) | 49 (0.17) | 42.9 (28.8 to 57.8) | 78.1 (70.5 to 84.5) |

| Day to day | 140 (0.27) | 49 (0.17) | 42.9 (28.8 to 57.8) | 82.9 (75.6 to 88.7) |

| Age >75 years | 191 (0.00) | 59 (0.00) | 72.9 (59.7 to 83.6) | 45.6 (38.3 to 52.9) |

The best performing individual items for LR−, LR+, and AUC were as follows: problems with ‘learn new gadget’ (LR− 0.22; 95% CI = 0.11 to 0.43), problems with ‘reasoning’ (LR+ 10.4; 95% CI = 5.06 to 21.5), and problems with ‘personal finance’ (AUC 0.80; 95% CI = 0.72 to 0.88) (Table 3). The optimal cut-point for diagnosis of dementia using age alone was 75.8 years (LR− 0.61; LR+ 1.40; AUC 0.60). In contrast the utility of the MMSE at a traditional cut-point of ≥24 indicating normality was LR− 0.28; LR+ 2.14; AUC 0.72, and the utility of memory problem noted by informant or participant was LR− 0.45; LR+ 1.10; AUC 0.55 suggesting this alone is not a useful diagnostic feature in this population.

Table 3.

Diagnostic utility of the best performing individual clinical items

| Clinical itema | N | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) | DOR (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | Youden (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reasoning | 219 | 10.4 (5.06 to 21.5) | 0.52 (0.39 to 0.68) | 20.2 (8.45 to 48.2) | 0.73 (0.66 to 0.80) | 0.46 (0.31 to 0.59) |

| Personal finance | 177 | 10.0 (5.14 to 19.5) | 0.36 (0.23 to 0.55) | 28.0 (11.1 to 70.3) | 0.80 (0.72 to 0.88) | 0.60 (0.43 to 0.73) |

| Often muddled | 153 | 9.20 (4.05 to 20.9) | 0.50 (0.37 to 0.67) | 18.5 (6.95 to 48.8) | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.81) | 0.47 (0.31 to 0.61) |

| Shopping money | 204 | 8.67 (4.33 to 17.4) | 0.53 (0.40 to 0.71) | 16.3 (6.86 to 38.8) | 0.72 (0.65 to 0.79) | 0.44 (0.28 to 0.58) |

| Everyday maths | 173 | 7.05 (3.94 to 12.6) | 0.38 (0.25 to 0.58) | 18.4 (7.80 to 43.2) | 0.78 (0.70 to 0.86) | 0.56 (0.39 to 0.69) |

| Learn new gadget | 209 | 2.30 (1.83 to 2.89) | 0.22 (0.11 to 0.43) | 10.7 (4.60 to 24.7) | 0.74 (0.68 to 0.81) | 0.49 (0.36 to 0.60) |

| Learn in general | 217 | 2.60 (2.01 to 3.37) | 0.27 (0.15 to 0.47) | 9.79 (4.62 to 20.7) | 0.75 (0.69 to 0.81) | 0.50 (0.37 to 0.62) |

| Recall difference place | 212 | 1.76 (1.45 to 2.13) | 0.27 (0.13 to 0.55) | 6.52 (2.87 to 15.0) | 0.69 (0.62 to 0.75) | 0.37 (0.24 to 0.49) |

| Forget where left things | 244 | 1.34 (1.18 to 1.52) | 0.28 (0.12 to 0.66) | 4.78 (1.87 to 12.2) | 0.61 (0.56 to 0.67) | 0.23 (0.13 to 0.33) |

| Any functioning problems | 217 | 1.48 (1.27 to 1.74) | 0.28 (0.13 to 0.61) | 5.28 (2.18 to 12.7) | 0.64 (0.59 to 0.70) | 0.39 (0.24 to 0.53) |

| Planning | 149 | 4.35 (2.78 to 6.83) | 0.29 (0.17 to 0.49) | 15.0 (6.49 to 34.8) | 0.79 (0.72 to 0.87) | 0.59 (0.42 to 0.71) |

| Recall where kept | 211 | 3.23 (2.32 to 4.50) | 0.35 (0.22 to 0.55) | 9.27 (4.56 to 18.9) | 0.75 (0.68 to 0.82) | 0.50 (0.35 to 0.63) |

AUC = area under receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve. DOR = diagnostic odds ratio. LR− = negative likelihood ratio. LR+ = positive likelihood ratio.

For details of clinical items see Appendix 1.

The results from the stepwise procedures using all or selected index items can be found in Table 4. There were 10 models meeting the criteria of predictive value and goodness of fit. All were better in terms of specificity than sensitivity and all but one had an AUC value ≥0.90. It was judged that the best overall model comprised problems with personal finance and planning (AUC 0.92, 95% CI = 0.86 to 0.97), but the model comprising personal finance and reasoning (AUC 0.86, 95% CI = 0.80 to 0.93) had almost as good a performance profile based on a larger sample size.

Table 4.

Diagnostic utility of the best models

| Modela | n | GOFb | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) | DOR (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finance + Planning | 114 | 0.95 | 23.7 (5.88 to 95.6) | 0.41 (0.27 to 0.62) | 57.8 (13.3 to -) | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.97) | 60.0 (42.1 to 76.1) | 97.5 (91.2 to 99.7) |

| Finance + Reasoning + Muddled + Money | 110 | 0.89 | ∞ | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.90) | ∞ (6.48 to ∞) | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.98) | 25.7 (12.5 to 43.3) | 100 (95.2 to 100) |

| Finance + Reasoning + Muddled + Maths + Money | 100 | 0.74 | ∞ | 0.73 (0.59 to 0.90) | ∞ (6.25 to ∞) | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.99) | 27.3 (13.3 to 45.5) | 100 (94.6 to 100) |

| Urinary incontinence + Planning + Maths | 106 | 0.66 | ∞ | 0.63 (0.48 to 0.82) | ∞ (11.0 to ∞) | 0.95 (0.91 to 1.00) | 37.5 (21.1 to 56.3) | 100 (95.1 to 100) |

| Finance + Reasoning + Muddled + Maths | 102 | 0.65 | ∞ | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.80) | ∞ (11.1 to ∞) | 0.92 (0.85 to 0.98) | 39.4 (22.9 to 57.9) | 100 (94.8 to 100) |

| Finance + Reasoning | 176 | 0.65 | ∞ | 0.55 (0.42 to 0.72) | ∞ (27.9 to ∞) | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.93) | 45.2 (29.9 to 61.3) | 100 (97.3 to 100) |

| Finance + Planning + Maths | 100 | 0.57 | 38.3 (5.34 to 274) | 0.44 (0.30 to 0.66) | 86.1 (13.2 to ∞) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) | 56.3 (37.7 to 73.6) | 98.5 (92.1 to 100) |

| Finance + Planning + Maths + Kept + Learn | 97 | 0.55 | 31.9 (4.41 to 231) | 0.52 (0.37 to 0.74) | ∞ 60.9 (9.35 to ∞) | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.00) | 48.4 (30.2 to 66.9) | 98.5 (91.8 to 100) |

| Finance + Reasoning + Muddled | 116 | 0.54 | ∞ | 0.64 (0.50 to 0.82) | ∞ (11.3 to ∞) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.97) | 36.1 (20.8 to 53.8) | 100 (95.5 to 100) |

| Finance + Planning + Maths + Recall | 97 | 0.40 | 31.9 (4.41 to 231) | 0.52 (0.37 to 0.74) | 60.9 (9.35 to ∞) | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.00) | 48.4 (30.2 to 66.9) | 98.5 (91.8 to 100) |

AUC = area under receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve. DOR = diagnostic odds ratio. LR− = negative likelihood ratio. LR+ = positive likelihood ratio. ∞ = infinity.

IQCODE items Question ‘Compared with 10 years ago how is this person at’ Finances = personal finance; Muddled = often muddled; Money = shopping money; Maths = everyday maths; Kept = recall where kept; Learn = learn in general. See also Appendix 1.

Goodness of fit (GOF) assessed using Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic where a higher P-value indicates a better goodness of fit.

Supplementary analyses when excluding the seven men who had an existing diagnosis of dementia, produced similar results for specificity, but sensitivity was lower (up to 20 percentage points). When analysing equivocal findings as normal the results were almost identical (to two decimal places) to the main analysis. Multiple imputation also resulted in similar results to the main analysis with specificity within 10% of the main estimates, but sensitivity often lower (up to 20 percentage points, details available from the authors). The AUC was consistent between imputed analyses and main.

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study found that combinations of simple questions had comparable or better diagnostic utility than the MMSE, with high utility for ruling-in a diagnosis, in men who were cognitively screened. Abnormal gait and primitive reflexes were the most useful physical findings. Some individual items were highly specific (for example, reasoning), whereas others were very sensitive (any memory difficulty reported by subject), but a combined approach enhanced their value.

Strengths and limitations

CaPS was not designed as a diagnostic test accuracy study, but, for the present study, a sample was selected with a high prior probability of some cognitive impairment from a larger population-based sample, with a broad spectrum of disease. A recognised reference standard was used, applied in consensus by experienced clinicians and a wide range of questionnaire items as well as neurological assessment were examined. Several models were tested that combined the best items. The reference standard was subject to incorporation bias (or circularity31) as results of the index tests could have been used in reaching a final diagnosis, but this is a common problem with clinical definitions of dementia. The estimates for diagnostic utility require validation in further studies, although the index test items were generally derived from well-validated instruments or standard clinical practice. When multiple-imputation was used to deal with the issue of missing data, there was minimal change in the specificity, but the sensitivity of the clinical items was, in general, lower. One limitation is that the study findings cannot be generalised to women, and there may be sex-related and socially-determined patterns in the performance of some index tests. Although the authors examined for interactions, they were underpowered to detect them.

The estimates of diagnostic utility may not generalise to other populations, with different prevalence of disease, as sampling was done on the basis of cognitive testing. The overall utility (AUC) of ‘any memory difficulty’ reported by either subject or informant was close to chance, suggesting that the sampling strategy oversampled men with cognitive impairment and hence would overestimate the PPV but would have underestimated the specificity.32 Other investigators have found that subjective memory problems are inconsistently associated with dementia.33 The estimates for diagnostic utility are likely to be overoptimistic as they result from stepwise selection procedures; some items may have been identified as being diagnostically useful by chance.

Comparison with existing literature

To the authors knowledge, this is the first study that has investigated the utility of such a broad range of clinical items for diagnosing dementia in a community-based sample. The results are supported by findings from other investigators who demonstrated that most diagnostic information in primary care was gained from age, functional assessment,34 and the clock drawing test (AUC 0.92).35 The diagnostic utility of an abnormal neurological examination36 and urinary incontinence37 were examined, which have been shown previously to be associated with dementia. Items on everyday maths, personal finances, and reasoning were all derived from IQCODE,26 and were previously found to have modest utility (AUC 0.85, 0.82, 0.82, respectively) in a case–control study in secondary care.38 As a whole, the IQCODE is sensitive (0.80) and specific (0.84) for diagnosing dementia,39 and functioning items have been found to be more discriminatory than memory items,40 which is in keeping with the present results.

Implications for research and practice

The current policy in the UK is to encourage GPs to diagnose dementia in typical elderly cases without referral11 unless there are specific reasons (for example, young age) that require a specialist opinion. Avoiding overdiagnosis (high specificity) may be more important than finding all possible cases (high sensitivity), as currently there are no drugs that modify the natural history of dementia41 and there are potential disadvantages from overdiagnosis.1,11,42

In this study, simple questions had high post-test probability of unspecified dementia. In principle, this raises the possibility that GPs who are considering dementia after evaluating a person with symptoms might be able to make the diagnosis, without specialist input, using relatively simple adjunct questions. GPs who are being asked to diagnose dementia in primary care might find measures of functional performance more useful than standard tests of cognition.

These findings, if replicated in other settings, would potentially be of clinical value in the assessment of patients who are frail and older, a group in whom post-mortem studies indicate a weaker association between neuropathology and clinical presentation.7 It is not the intention that these questions should be used in isolation to diagnose dementia, but rather that they have added value after routine clinical assessment. This should not preclude the consideration of reversible causes of cognitive impairment (for example, infection or depression), the use of further investigations to exclude pathologies (for example, space-occupying-lesion) that mimic dementia, or specialist referral for dementia subtype diagnosis. Such a two-pronged approach would enable GP diagnosis for some patients, with advanced work-up and referral being reserved for scenarios where diagnostic uncertainty persists.43 The utility of the observations in routine clinical settings requires further research. A prospective diagnostic test accuracy study is being conducted to validate these preliminary findings in men and women, and to quantify the incremental value of tests in the context of GP clinical suspicion of possible dementia.

Acknowledgments

Professor Shah Ebrahim obtained funding for and helped design CaPS phase 5. We thank the reviewers and Professor Sarah Purdy for providing helpful comments that improved the manuscript. This study was presented at a UK academic general practice trainees conference, Oxford, April 2014.

Appendix 1. Details of items in index test evaluation

| Item (full details) | Referred to in manuscript as |

|---|---|

| Initial questions: asked of both subject and informant | |

| Have any difficulty with your memory? | Any memory difficulty |

| Forget where you left things more than you used to? | Forget where left things |

| Forget what you were going to do, on the way to doing it? | Forget what going to do |

| Forget names of close friends or relatives? | Forget names |

| Ever forgotten your way or got lost in own neighbourhood? | Get lost |

| Forget what said & ask same question over & over? | Repeat question |

| Aware of memory problem | Aware of problem |

| Difficulty finding word you want to say? | Word finding difficulty |

| Sometimes say the wrong word? | Wrong word |

|

| |

| Interviewer observations | |

| Self-neglect | Interviewer: Self-neglect |

| Uncooperative behaviour | Interviewer: Uncooperative |

| Suspiciousness | Interviewer: Suspiciousnessa |

| Hostile/irritable | Interviewer: Hostilea |

| Incongruent/bizarre | Interviewer: Bizarrea |

| Slow/underactive | Interviewer: Slow |

| Restless | Interviewer: Restless |

| Anxious out of proportion to situation | Interviewer: Anxious |

| Looks depressed | Interviewer: depressed |

| Emotional lability | Interviewer: Labilea |

| Flat affect | Interviewer: Flat |

| Appears to be hallucinating | Interviewer: Hallucinatinga |

| Rapid speech | Interviewer: Rapid speech |

| Slow speech | Interviewer: Slow speech |

| No spontaneous speech, restricted in quantity | Interviewer: limited speech |

| Speech rambling, incoherent, irrelevant | Interviewer: Speech rambling |

| Speech slurred | Interviewer: Speech slurred |

| Perseverating | Interviewer: Perseveratinga |

| No insight | Interviewer: No insight |

| Clouding of consciousness | Interviewer: Clouding of consciousnessa |

| Peculiar use of terms | Interviewer: Peculiar terms |

| Speaking to self | Interviewer: Speaking to self |

| Impaired ability to focus, shift or sustain attention | Interviewer: Impaired focus |

| Impaired judgement of situations or persons | Interviewer: Impaired judgement |

| Hypochondriacal preoccupations with somatic discomfort | Interviewer: Hypochondriacala |

| Repetitive conversation | Interviewer: Repetitive |

| Spontaneously talking about distant past | Interviewer: Distant past |

|

| |

| Examination Findings | |

| Other significant findings | Other significant findings |

| Cranial Nerve abnormality | Cranial nerve defect |

| Field defect | Field defect |

| Horner Syndrome | Horner’s |

| Acuity | Acuity |

| Ophthalmoplegia | Ophthalmoplegia |

| VII cranial nerve deficit | Facial nerve palsy |

| Hearing difficulty | Hearing difficulty |

| Pseudo-bulbar palsy | Pseudo-bulbar palsy |

| Bulbar palsy | Bulbar palsy |

| Speech disturbance: Dysarthria | Dysarthria |

| Gait disturbance any | Any Gait disturbance |

| Gait disturbance: Parkinsonian/Apraxic | Parkinsonian gait |

| Gait disturbance: Spastic | Spastic gait |

| Gait disturbance: Ataxic | Ataxic gait |

| Gait disturbance: Antalgic | Antalgic gait |

|

| |

| Pyramidal Signs (not clinically due to myelopathy): on right, left or absent | Significant pyramidal signs |

| Drift | Drift |

| Weakness | Weakness |

| Hypertonia | Hypertonia |

| Hyperreflexia | Hyperreflexia |

| Babinski | Babinski |

| Extrapyramidal Signs | Significant Extrapyramidal Signs |

| Rigidity | Rigidity |

| Bradykinesia | Bradykinesia |

| Tremor | Tremor |

| Postural instability | Postural instability |

| Asymmetric deficit | Asymmetric deficit |

| Central Sensory disturbance (not peripheral nerve) | Sensory disturbance |

| Cerebellar signs | Cerebellar signs |

| Other localising signs | Other localising signs |

| Primitive reflexes | Any primitive reflexes |

| Palmomental | Palmomental |

| Pout | Pout |

| Grasp | Grasp |

|

| |

| IQCode. Compared with 10 years ago how is this person at: | |

| Remembering things about family and friends (for example, birthdays, occupations, addresses) | Family and friends |

| Remembering things that have happened recently | Recall recent events |

| Recalling conversations a few days later | Recall conversations |

| Remembering own address and telephone number | Recall own address |

| Remembering what day and month it is | Recall day |

| Remembering where things are usually kept | Recall where kept |

| Remembering where to find things put in a different place from usual | Recall difference place |

| Working familiar household appliances | Work appliances |

| Learning to use new gadget or appliance around the house | Learn new gadget |

| Learning new things in general | Learn in general |

| Following a story in a book or on TV | Follow story |

| Making decisions on everyday matters | Decisions |

| Handling money for shopping | Shopping money |

| Handling personal finance (for example, pension, bank) | Personal finance |

| Handling everyday arithmetic (for example, how much food to buy, time between visits from friends/family | Everyday maths |

| Using intelligence to understand what’s going on and to reason things through | Reasoning |

|

| |

| Everyday Activities (asked of both subject and informant) | |

| Any problems with daily activities | Any ADL problems |

| Difficulty feeding self | Feeding |

| Change in eating habit | Appetite |

| Difficulty dressing | Dressing |

| Needing assistance with bathing/washing/toileting | Toileting |

| Decreased attention to personal hygiene | Hygiene |

|

| |

| Physical Symptoms (informant) | |

| Physical symptoms (any) | Any physical symptoms |

| Urinary | Urinary incontinence |

| Faecal | Faecal incontinence |

| Tendency to fall | Falls |

| Syncope/unexplained loss of consciousness | Syncope |

|

| |

| General Functioning report (informant) | |

| General functioning any problems | Any functioning problems |

| Tends to talk about distant past rather than present | Distant past |

| Loss of special skill or hobby | Hobby |

| Thinking often muddled | Often muddled |

| Greater difficulty thinking and planning ahead | Planning |

| Difficulty concentrating, more distractible | Concentrating |

| Talking more than previously | Talk more |

| Talking less than previously | Talk less |

| Repeating words or phrases | Repeat words |

| Fails to realise extent of any problems | No insight |

|

| |

| Personality/emotion/behaviour (informant) | |

| Any personality change | Any personality change |

| Emotional lability | Labile |

| Emotional blunting | Blunting |

| Lack of motivation and spontaneous behaviour | Unmotivated |

| Breaches of social etiquette/disinhibited behaviour | Disinhibited |

| Perservative/stereotyped behaviour | Perseveration |

| Sleep pattern disturbance | Sleep disturbed |

| Aggression | Aggressive |

| Narrowed preoccupations | Narrowed preoccupations |

| Mental rigidity | Mental rigidity |

| Hyperorality (increased oral behaviours) | Hyperorality |

| Auditory hallucinations | Auditory hallucinations |

| Visual hallucinations | Visual hallucinations |

| Would (Has) subject cope (d) alone without partner/cohabitee? | Unable cope alone |

|

| |

| Symptom onset and progression | |

| Onset | Months since onset: more than 12 |

| Course of symptoms | Course not improving |

|

| |

| Symptom fluctuation | Symptom fluctuation (any) |

| Hour to hour | Hour to hour |

| Day to night | Day to night |

| Day to day | Day to day |

| Week to week | Week to weeka |

| Accommodation not own home | Accommodation not own home |

Indicates features which were not identified in any men and so diagnostic utility could not be calculated. ADL = activities of daily living.

Funding

The main Caerphilly study was funded by an intramural grant to Medical Research Council Epidemiology Unit (Cardiff). The Alzheimer’s Society funded the phase 5 follow-up. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for phase 5 was provided by Gwent Research Ethics Committee (01/69).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Le Couteur DG, Doust J, Creasey H, Brayne C. Political drive to screen for pre-dementia: not evidence based and ignores the harms of diagnosis. BMJ. 2013;347(sep09_21):f5125. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns A. Alistair Burns and 51 colleagues reply to David Le Couteur and colleagues. BMJ. 2013;347(oct15_6):f6125. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox C, Lafortune L, Boustani M, Brayne C. The pros and cons of early diagnosis in dementia. Br J Gen Pract. 2013 doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X669374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmad S, Orrell M, Iliffe S, Gracie A. GPs’ attitudes, awareness, and practice regarding early diagnosis of dementia. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X515386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manthorpe J, Samsi K, Campbell S, et al. From forgetfulness to dementia: clinical and commissioning implications of diagnostic experiences. Br J Gen Pract. 2013 doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X660805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews FE, Brayne C, Lowe J, et al. Epidemiological pathology of dementia: attributable-risks at death in the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. PLoS Med. 2009;6(11):e1000180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuropathology Group Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Aging Study. Pathological correlates of late-onset dementia in a multicentre, community-based population in England and Wales. Neuropathology Group of the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC CFAS) Lancet. 2001;357(9251):169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savva GM, Wharton SB, Ince PG, et al. Age, neuropathology, and dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(22):2302–2309. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodd E, Cheston R, Fear T, et al. An evaluation of primary care led dementia diagnostic services in Bristol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):592. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0592-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greaves I, Greaves N, Walker E, et al. Gnosall Primary Care Memory Clinic: Eldercare facilitator role description and development. Dementia. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1471301213497737. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunet M. Targets for dementia diagnoses will lead to overdiagnosis. BMJ. 2014;348(apr01_2):g2224. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Support for commissioning dementia care NICE commissioning guides [CMG48] 51 Improving early identification, assessment and diagnosis. London: NICE; 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cmg48/chapter/51-improving-early-identification-assessment-and-diagnosis. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dua T, Barbui C, Clark N, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: summary of WHO recommendations. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11):e1001122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Hout HPJ, Vernooij-Dassen MJFM, Hoefnagels WHL, et al. Dementia: predictors of diagnostic accuracy and the contribution of diagnostic recommendations. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(8):693–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, et al. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37(3):323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cruz-Orduña I, Bellón JM, Torrero P, et al. Detecting MCI and dementia in primary care: effectiveness of the MMS, the FAQ and the IQCODE [corrected] Fam Pract. 2012;29(4):401–406. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GBB, et al. Community screening for dementia: The Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) compared. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(4):377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch T, Iliffe S. Rapid appraisal of barriers to the diagnosis and management of patients with dementia in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Caerphilly and Speedwell Collaborative Group Caerphilly and Speedwell collaborative heart disease studies. The Caerphilly and Speedwell Collaborative Group. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1984;38(3):259–262. doi: 10.1136/jech.38.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fish M, Bayer A, Gallacher JEJ, et al. Prevalence and pattern of cognitive impairment in a community cohort of men in South Wales: methodology and findings from the Caerphilly Prospective Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;30(1):25–33. doi: 10.1159/000115439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. (DSM-IV-TR) [Internet]. Text. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roth M, Tym E, Mountjoy CQ, et al. CAMDEX. A standardised instrument for the diagnosis of mental disorder in the elderly with special reference to the early detection of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149:698–709. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.6.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, Pillon B. The FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology. 2000;55(11):1621–1626. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jorm AF, Korten AE. Assessment of cognitive decline in the elderly by informant interview. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:209–213. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meng X, D’Arcy C, Morgan D, Mousseau DD. Predicting the risk of dementia among Canadian seniors: a useable practice-friendly diagnostic algorithm. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27(1):23–9. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318247a0dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin J, Tian L. Optimal linear combinations of multiple diagnostic biomarkers based on Youden index. Stat Med. 2014;33(8):1426–1440. doi: 10.1002/sim.6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosmer DW, Lemesbow S. Goodness of fit tests for the multiple logistic regression model. Commun Stat Methods. 1980;9(10):1043–1069. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Buuren S, Boshuizen HC, Knook DL. Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):681–694. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<681::aid-sim71>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Worster A, Carpenter C. Incorporation bias in studies of diagnostic tests: how to avoid being biased about bias. CJEM. 2008;10(2):174–175. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500009891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leeflang MMG, Rutjes AWS, Reitsma JB, et al. Variation of a test’s sensitivity and specificity with disease prevalence. CMAJ. 2013;185(11):E537–544. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reid LM, Maclullich AMJ. Subjective memory complaints and cognitive impairment in older people. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(5–6):471–485. doi: 10.1159/000096295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heyrman J, Dessers L, de Munter M-B, et al. Functional status assessment in the elderly. In: Wonca Classification Committee, editor. Functional status measurement in primary care. New York, NY: Springer; 1990. pp. 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Lepeleire J, Heyrman J, Baro F, Buntinx F. A combination of tests for the diagnosis of dementia had a significant diagnostic value. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(3):217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olazarán J, Torrero P, Cruz I, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and dementia in primary care: the value of medical history. Fam Pract. 2011;28(4):385–392. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grant RL, Drennan VM, Rait G, et al. First diagnosis and management of incontinence in older people with and without dementia in primary care: a cohort study using The Health Improvement Network primary care database. PLoS Med. 2013;10(8):e1001505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perroco TR, Bustamante SEZ, Moreno MDPQ, et al. Performance of Brazilian long and short IQCODE on the screening of dementia in elderly people with low education. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(3):531–538. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209008849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quinn TJ, Fearon P, Noel-Storr AH, et al. Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) for the diagnosis of dementia within community dwelling populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD010079. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010079.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sikkes SAM, Knol DL, van den Berg MT, et al. An informant questionnaire for detecting Alzheimer’s disease: are some items better than others? J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17(4):674–681. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon PJ. No evidence exists that ‘anti-dementia’ drugs modify disease or improve outcome. BMJ. 2014;348:g2607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunet MD, McCartney M, Heath I, et al. There is no evidence base for proposed dementia screening. BMJ. 2012;345:e8588. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Health Quality Ontario The appropriate use of neuroimaging in the diagnostic work-up of dementia: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14(1):1–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]