Abstract

Mounting evidence indicates Community Health Workers (CHWs) contribute to improved behavioral and health outcomes and reductions in health disparities. We provide an overview (based on grantee reports and community action plans) that describe CHW contributions to 22 Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) programs funded by CDC from 2007–2012, offering additional evidence of their contributions to the effectiveness of community public health programs. We then highlight how CHWs helped deliver REACH U.S. community interventions to meet differing needs across communities to bridge the gap between health care services and community members; build community and individual capacity to plan and implement interventions addressing multiple chronic health conditions; and meet community needs in a culturally appropriate manner. The experience, skills, and success gained by CHWs participating in the REACH U.S. program have fostered important individual and community-level changes geared to increase health equity. Finally, we underscore the importance of CHWs being embedded within these communities and the flexibility they offer to intervention strategies, both of which are characteristics critical to meeting the needs of communities experiencing health disparities. CHWs served a vital role in facilitating and leading changes and will continue to do so.

Keywords: REACH U.S. Community Health Workers, health inequity, racial and ethic health disparities

INTRODUCTION

People of color are disproportionately burdened by chronic disease. In the United States, the resulting health disparities cost $229.4 billion in direct medical expenditures from 2003 to 2006 (LaVeist, Gaskin, & Richard, 2009). Between 2007 and 2009, African Americans continued to have a shorter healthy life expectancy than Whites, with significant regional disparities in life expectancy between African Americans and Whites in the southeast part of the country (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013). This gap is growing and is attributed primarily to social determinants among African Americans, such as segregation; discrimination; and lack of adequate housing, education, transportation, and access to culturally and community-relevant health care (Flores, 2010; Orsi, Margellos-Anast, & Whitman, 2010). The impact of these factors reaches far beyond people relying on safety net programs for all Americans and calls for a culturally competent solution that will be equally sweeping in its reach across disparate communities (Orsi, 2010).

There is mounting evidence that CHWs (also known by other titles such as community health advisor, community health advocate, outreach worker, community health representative, promotora/promotores de salud [health promoter], patient navigator, navigator promotoras, peer counselor, lay health advisor, peer health advisor, and peer leader) serve effectively in multiple roles in initiatives designed to improve the health of individuals and communities (Brownstein, Andrews, Wall, & Mukhtar, 2011). Studies show that CHWs have decreased the number of emergency room visits among disparate populations by as much as 40% (Fedder, Chang, Curry, & Nichols, 2003) and CHWs have provided a return on investment of more than $2.28 for every $1 invested by shifting inpatient and urgent care to primary care (Whitley, Everhart, & Wright, 2006). These types of results, coupled with CHWs’ contributions to increased patient knowledge and to improved behavioral and health outcomes in multiple health priority areas, represent reductions in health disparities and have sparked a growing interest in advancing the CHW frontline workforce (Comprehensive Health Education Foundation, 2013), For example, in 2010, the Department of Labor recognized the CHW workforce, and various federal, state, and other entities acknowledged CHWs as necessary members of community health teams that have a patient-centered perspective and a preventive approach, especially in underserved communities (Brownstein et al., 2011; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2013; Children’s Health Insurance Plan Reauthorization Amendment, 2009; Comprehensive Health Education Foundation, 2013; Kurzweil & Morgan; Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2010; Whitley, et al., 2006).

In this paper, we summarize the perspectives and contributions of CHWs who participated in implementing 22 CDC-funded Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) program initiatives through REACH U.S. to address racial and ethnic health disparities across a number of health priority areas and priority populations. In 2007, CDC funded 40 REACH U.S. community programs to reduce and eliminate racial and ethnic health disparities by implementing culturally tailored, community-led interventions and addressing one or more health priority areas. We discuss in broad terms the contributions that CHWs, working across their many roles, have made to eliminate health disparities across REACH U.S. communities. Table 1 provides specific examples of these contributions in individual REACH U.S. communities.

Table 1.

REACH U.S. Program Examples Illustrating How Community Health Workers (CHWs) Can Help Address the Needs of Health Disparate Communities

| Challenge | Strategy | Practices | Results | Community |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrating social determinants into health services | Linking health and housing resources | CHW input was used to develop and disseminate housing resource tools to clients/families, clinicians, and other health care providers, with a focus on access and navigation of housing resources for clients dealing with habitability issues. Services included education about housing code enforcement, legal aid, tenant rights, and links to affordable housing. Additional services focused on policy changes related to improving access to medications and immunizations. | 64% reduction in emergency room visits. This program demonstrates a return on investment of $1.46 for every $1 invested in the program as a whole. | Regional Asthma Management and Prevention (RAMP), Public Health Institute, Oakland, California |

| Developing youth leaders | After school program for training youth | A REACH U.S. program in Arizona collaborated with the REACH coalition to develop youth-based CHW programs, such as a teen health careers club addressing health disparities and cervical cancer prevention. The youth developed a play to raise awareness around the human papillomavirus vaccine and conducted outreach. In another afterschool program, called Kids with a Positive Attitude (KAPA), students used PhotoVoice to demonstrate their perspectives of the needs and barriers to health within their community. | Participating teens used pictures to depict their interpretation of the health of the neighborhood. These pictures are included in the City Master Plan. | To Our Children’s Future with Health, Philadelphia, PA |

| Developing toolkit for education and advocacy | Developed and disseminated a toolkit for developing coalition action and advocacy for breast/cervical cancer and as well as trained grassroots leaders. | Community Health Advocates’ efforts resulted in the passage of House Bill 147, which expands treatment through Medicaid for eligible women diagnosed with breast/cervical cancer. Four states (Kentucky, Mississippi, Alaska, and Louisiana) and more than 50 CHWs (referred to as community health advocates in this community) have used the University of Alabama’s toolkit to adopt the grassroots approach to expanding insurance coverage. | University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL. | |

| Increasing access to needed supplies for managing chronic conditions | Generating funding and purchasing supplies | Annually, community health advocates write and produce a play that is presented as Dinner Theater to raise money to provide glucose monitoring strips and other supplies for managing diabetes. Other fundraising methods also were used to generate income to help those with very limited incomes. | The program was established to assist people without insurance or income to purchase glucose monitoring strips and other supplies. A1C dropped from a mean of 10.3 to 7.2 for people who participated in the program for more than 3 months. | Charleston and Georgetown Diabetes Coalition, REACH U.S. SEA-CEED, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston and Georgetown, South Carolina |

| Improving physical activity, and/or healthy eating | Working with others to address needs | CHWs promoted change by encouraging others to assist them in influencing administrators/managers of local organizations to adopt the “Fit Friendly” program. They also promoted adoption of heart and stroke information and instructions for the appropriate use of 9-1-1 in employee orientation and annual mandatory safety updates of community-based organizations in Denver, Colorado. | Adopted the “Fit Friendly” program and 9-1-1employee orientation, and updated an established and ongoing education program. | University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, Aurora, Colorado |

| Meeting community needs | Working with others to address needs | Many women lacked information about breast and cervical cancer. Although Vietnamese women have four to five times the incidence rate of cervical cancer as non-Hispanic white women nationwide, talking about cancer was stigmatized within the community before the work of the CHWs, called patient navigators in this REACH U.S. community. The CHWs, respected members of this Vietnamese community, were able to introduce new concepts in a culturally appropriate manner and to create a comfortable environment in which a formerly taboo subject could be discussed. | The nickname “cancer ladies” was given to the CHWs and became an honorable title among Vietnamese women across the U.S. who requested assistance with disease detection and prevention. This particular community began viewing the CHWs as “sister” figures who provide support and access to health care resources. | Orange County Asian and Pacific Islander Community Alliance, Orange County, Garden Grove, California |

| A review board for community interventions was created, where CHWs and others assessed the nature of the project. | Identified changes in community needs | Greater Lawrence Family Health Center, Lawrence, Massachusetts | ||

| CHWs assist in mapping the service area by conducting a “windshield tour” for health providers. | Health providers see first-hand the health challenges faced by their patients. Dental services for clients were one of the needs identified and addressed through the Baxter Community Health Clinic. | Genesee County Health Department, Flint, Michigan | ||

| Addressing community leadership gaps | CHW model dissemination | In Arizona, two community health centers turned to the REACH U.S. Pima County Arizona program as a source for experienced CHWs and have hired REACH-trained CHWs. | CHWs improved the ability of REACH U.S. programs to meet the needs of health disparate communities in key health priority areas. For example, CHWs educated members of border communities on human papillomavirus and cervical cancer prevention. Based on its success, the outreach workgroup decided to work toward integrating CHW’s\promotoras into every community health center in Pima County. | University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona |

| Formal CHW training | The Center for Excellence in Eliminating Disparities at the University of Illinois at Chicago is developing new curricula to train CHWs on healthy eating and physical activity using information gathered from current CHWs. The center will ask the CHWs about their personal experiences, questions they have been asked by clients, issues they have observed, and the cultural norms of their communities. | Development of high-quality, evidence-based curricula that are relevant to Latino and African American communities that can be used by CHWs in multiple settings to carry the message that healthy eating and physical activity are critical to healthier lives. | Center for Excellence in Eliminating Disparities, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois | |

| Increasing or leveraging policy and systems change | Developing statewide guidelines for diabetes care | CHWs joined with South Carolina Department of Health and health care providers to develop, advocate, and implement statewide guidelines for diabetes care that addresses the unique needs of certain racial and ethnic groups. | South Carolina Guidelines for Diabetes Care have incorporated the identified unique differences of various racial and ethnic groups. The South Carolina legislature has established laws that encourage adopting guidelines. The guidelines have been distributed statewide and are available at www.musc.edu/reach Diabetes care has improved and diabetes-related hospitalizations and emergency department visits for amputations have been reduced by more than 50%. | Charleston and Georgetown Diabetes Coalition, REACH U.S. SEA-CEED, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina |

| Lack of evaluation | Evaluation by partner organizations | At Sinai Institute, a study revealed an $8 return on investment when case management and reinforced education were delivered. | The efforts of partner liaisons at the L.A. BioMedical REACH U.S. program contributes to the reduction in the disparities in influenza immunization rates by demonstrating a 10% rate increase in African American and Hispanic populations during 2007-2010. University of Illinois at Chicago has demonstrated favorable returns on investment in the strategies and interventions. |

Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois |

Multiple CHW Models

Common CHW roles have been integrated into evidence-based models: CHWs serve as effective links between vulnerable populations and health care; manage care; provide culturally appropriate health education; ensure cultural competence of health services; advocate for underserved individuals; provide informal counseling; and build community capacity (to identify, plan and implement interventions to improve health outcomes) (Rosenthal, et al., 1998; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2011). Other significant CHW contributions to REACH communities have included serving as change agents; bridging the gap between health and social services and communities; serving as leaders of health equity and social justice; and providing cost-effective and evidence-based services to eliminate barriers to health (Brownstein et al., 2011).

In this paper, we offer additional evidence of the importance of CHWs’ contributions to local community public health programs and discuss the importance of CHWs in bridging the gap between health care services and community members; building community and individual capacity to plan and implement interventions that address multiple chronic health conditions; and meeting community needs in a culturally appropriate manner. We then highlight how CHWs have engaged in delivering REACH U.S. community interventions that have successfully met differing needs across communities in ways that underscore the importance of CHWs embedment within these communities and the flexibility they offer to intervention strategies—characteristics that we conclude are critical to meeting the needs of communities experiencing health disparities.

Gaps in Health Care

As members of the communities they serve, CHWs contribute to culturally relevant care in health care systems by helping health care providers understand and address barriers associated with a community’s historical and cultural context, including barriers to health care associated with differences in language and culture (Brownstein et al, 2011). Millions of people who lack proficiency in the English language or knowledge of U.S culture have immigrated to the United States. Many of these people reside in cultural enclaves where traditions and practices, including those directly relevant to health practices and norms, continue to thrive across generations (Ransford, Carrillo, & Rivera, 2010). Understanding the culture and practices of these communities is essential to developing innovative and relevant solutions for improving health among community members. Health care providers serving diverse communities often lack knowledge of a community’s language, culture, and historical context, making it difficult to effectively assist underserved communities (Viswanathan, et al., 2010).

REACH CHWs are effective cultural brokers who help bridge gaps between existing services and community needs by addressing key social determinants of health (see Table 1). Being embedded within the community they serve often enables them to work nontraditional office hours and in more convenient locations for assisting community members (e.g., in homes, places of worship, barbershops, malls). In doing so, CHWs increase their accessibility to community members who lack transportation or who cannot leave work to access health services. Table 1 includes specific examples of CHWs’ roles and activities in REACH U.S. communities.

Educating CHWs in Building Community Capacity

Including CHWs in REACH U.S. interventions has been an effective strategy for building community capacity to provide effective public health services to community members. To help ensure success, REACH U.S. coalitions educated CHWs about the social and environmental factors influencing community public health outcomes and provided CHWs with extensive training in health priority area(s) and leadership skills, including educating and organizing REACH communities. In turn, the CHWs built community capacity by educating community organizations about health issues and how to address them in their communities. CHWs were involved in various aspects of program planning and implementation, such as assisting in linking community organizations and serving as client advocates. CHWs also increased community capacity through a range of interventions, including providing patient outreach and navigation, supporting patients in medical homes, assisting with community institutional review board processes, and providing feedback on the quality health care and the needs of the community. CHWs improved the responsiveness of health care providers, other organizations, and policy makers by presenting at academic and professional meetings, contributing to manuscripts, presenting to community health providers and organizations and engaging in other interactions such as training grassroots leaders.

CHWs also built the capacity of individual community members to prevent and manage their chronic disease(s), raised community members’ health literacy levels, navigated complicated systems inside and outside health care services, provided culturally appropriate support, helped explain medical terms, assisted clients in eligibility screenings and applications, and assisted coalitions in tailoring interventions and developing curricula and training programs for future CHWs. These actions helped community coalitions reach greater numbers of people in their most disparate communities.

Addressing Community Needs across Varying Contexts

The literature is growing regarding the importance of culturally tailoring interventions and engaging CHWs as key strategists in addressing racial and ethnic health disparities. REACH U.S. programs found that engaging CHWs was a critical part of addressing communities’ needs in ways that were sensitive to local cultural and historical contexts. CHWs helped identify community needs and filled gaps in access to care by linking community members and organizations to health services, providing public health resources and education to support healthy behaviors, and serving as advocates for individual and community health. Because they felt passionate about their work and often resided in the communities they served, the CHWs gained community trust and effectively positioned themselves to educate community leaders and inform policy and system changes (see Table 1).

For example, in the University of Colorado’s Fit Friendly Program, the CHWs earned community trust, enabling them to effectively educate community members and foster the adoption of school and worksite wellness initiatives. The Medical University of South Carolina engaged CHWs when educating decision makers about changes in health care reimbursement policies and the need to ensure proper standards of care. The Regional Asthma Management and Prevention (RAMP) initiative engaged CHWs to educate stakeholders on the benefits of revising housing codes. The University of Arizona’s Marana Community Health Center enabled CHWs to facilitate health screening for patients enrolled in Medicaid who were out of compliance with screening guidelines. CHWs contributed to the University of Alabama’s efforts that resulted in expanding treatment through Medicaid for eligible women diagnosed with breast/cervical cancer.

Across many of the REACH sites, CHWs helped address community needs by educating leaders on the importance of addressing social determinants of health, including access to both transportation and safe affordable housing. CHWs also helped educate the public through radio and other media-based education initiatives. Finally, CHWs supported efforts to develop infrastructure (e.g., community gardens) and to deliver public health interventions (e.g., fitness programs).

Gaining community trust was critical for CHWs to successfully bridge gaps between health care systems and patients. This trust positioned CHWs to serve as advocates to help community members navigate the health care system and provide them with a personal level of attention not typical of public health systems. Being embedded in the communities allowed CHWs to meet with clients at grocery stores and other convenient locations. CHWs even accompanied clients who did not have transportation to their health care appointments and assisted them with understanding and adhering to health providers’ recommendations.

Evaluating CHWs’ Efforts: Putting Research into Practice

The training provided to CHWs by REACH Coalitions represents a significant investment to build and extend the community capacity needed to reduce and eliminate racial and ethnic health disparities. However, no widely accepted evaluation approach exists for assessing CHWs’ contributions toward preventing, managing, and reducing the incidence and prevalence of chronic disease in health disparate communities. Therefore, REACH coalitions shared their evaluation and assessment strategies with each other and, in so doing, they discovered a common emphasis on community-based participatory approaches. The REACH coalitions found that engaging CHWs in the evaluation process was helpful, not only to build CHW capacity to provide the necessary services but also because the unique perspectives and roles of CHWs strengthened their evaluation efforts. While coalition members and CHWs needed to be trained in evaluation strategies, program evaluators benefited from the trusting relationships that coalition members and CHWs had established in communities. The special role of CHWs enabled them to communicate the purposes of the evaluation efforts to multiple stakeholders, including providers, patients, and the community at large. This communication helped to ensure a wider understanding of the purposes of evaluation and data collection, and allowed for greater community control over the evaluation data and its use, thereby fostering greater buy-in to the evaluation and to using the evaluation’s findings. REACH coalition members and CHWs participated together in disseminating results, preparing manuscripts, and presenting at professional conferences and to community residents.

More broadly, CHWs offered a unique perspective on the REACH Coalitions’ evaluation efforts and helped to balance the need to assess impact with other needs, including sustaining the coalitions’ public health interventions and identifying unmet and emerging community needs. With CHW input, REACH coalitions also identified and used a broader spectrum of evaluation strategies, including documenting community stories as well as using PhotoVoice and focus groups to help inform the intervention strategies (summarized in Table 1) and capture rich insights into the roles, responsibilities, training, ongoing activities, and effectiveness of REACH U.S. CHWs.

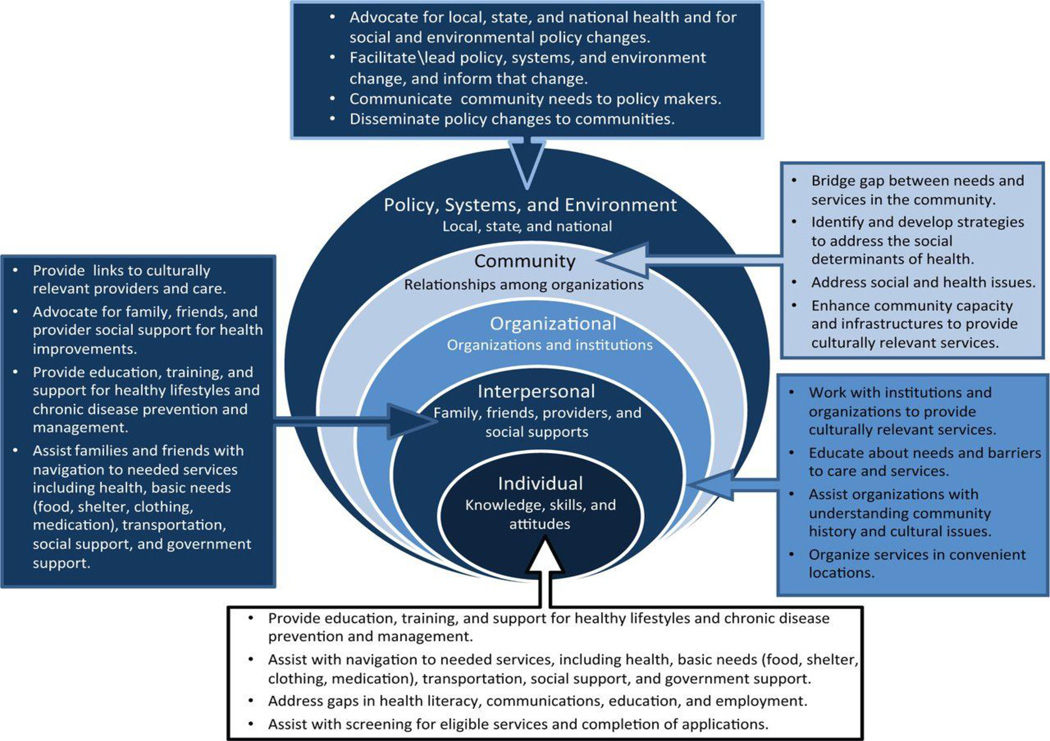

This review demonstrates the large potential for CHWs to fill the gaps across all levels of the socio-ecological model as summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conclusion

The level of engagement of CHWs by more than half of the REACH U.S. programs underscores the importance that experienced practitioners place on CHWs as part of an effective strategy to address racial and ethnic health disparities. REACH CHW models provide community members with a vehicle to communicate their experiences and views on health, reframing the traditional approach to medicine and, ultimately, to the health care system. As brokers of culture, language, and health literacy, CHWs serve as gatekeepers to ensure access to quality health services. They build trust in the community that fosters the foundation for a healthy and sustainable relationship between patients and providers. The review demonstrates the large potential for CHWs to transcend multiple models, fill the gaps in health services, build community capacity, address community needs, and assist in the evaluation of programs, policy, systems and environmental changes to promote health equity in racial and ethnic communities.

As indicated by the 22 REACH U.S. communities, CHWs have the unique ability to reach racial and ethnic populations. It is important to note that among the REACH programs CHWs, and other program providers and researchers learned from each other’s perspective. The activities and formal evaluations listed in this paper and in the included table could inform future research and practical implementation of the roles, activities, and efforts of CHWs in diverse, underserved racial and ethnic communities.

REACH U.S. programs model the strengths of CHWs in working across various levels of the socio-ecological model and addressing each aspect — from individual to local policy and systems change. Many CHWs begin with outreach and education and then advocate for community and systems change, thereby ensuring the sustainability of the change they are helping to create.

The experience, skills, and success gained by CHW participating in the REACH U.S. program has fostered significant individual and community-level changes geared to improve racial justice. The REACH movement provides the resources necessary for people to improve health equity so that race and ethnicity may no longer be a determinant of one’s health. CHWs have served a vital role in leading that change and will continue to do so.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Shannon Cosgrove, Health Equity, YMCA of the USA, Washington, DC, USA.

Martha Monroy, University of Arizona Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, Center of Excellence in Women’s Health, Tucson, AZ, USA.

Carolyn Jenkins, Community Engagement, South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Institute, REACH U.S. SEA-CEED Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA.

Sheila R. Castillo, Midwest Latino Health Research, Training and Policy Center, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Charles Williams, Public Health Partnerships, Neighborhood Initiatives - University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Erlinda Parris, Midwest Latino Health Research, Training and Policy Center, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Jacqueline H. Tran, Health Programs, Orange County Asian and Pacific Islander Community Alliance, Garden Grove, CA, USA.

Mark D. Rivera, Division of Community Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

J. Nell Brownstein, Division for Heart disease and Stoke Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

REFERENCES

- Brownstein JN, Andrews T, Wall H, Mukhtar Q. Addressing chronic disease through community health workers: A policy and systems level approach. 2011 Retrieved December 16, 2013, from http://www.chw-nec.org/pdf/CHW_BRIEF_B_4.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State-specific healthy life expectancy at age 65 years—United States, 2007–2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62:561–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Health Insurance Plan Reauthorization Amendment. PL 111-003; 2009. Sec.302, Outreach and Enrollment. 2009 Retrieved December 16, 2013, from http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ3/pdf/PLAW-111publ3.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Update on Preventive Services initiatives (letter) 2013 Retrieved from http://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/SMD-13-002.pdf.

- Comprehensive Health Education Foundation. Community health worker white paper: Report and recommendations. 2013 Retrieved December 21, 2013, from http://www.chef.org/Portals/0/CHW/FinalChwWhitePaper.pdf.

- Fedder DO, Chang RJ, Curry S, Nichols G. The effectiveness of a community health worker outreach program on healthcare utilization of west Baltimore City Medicaid patients with diabetes, with or without hypertension. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13:22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzweil R, Morgan MJ. Examples of state and local integration of community health workers. (n.d.). Retrieved December 21, 2013, from Peers for Progress Web site: http://peersforprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/20131206_wg6_examples_of_state_and_local_integration_of_chws.pd.

- LaVeist T, Gaskin D, Richard P. The economic burden of health inequalities in the United States. Washington, DC: Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies; 2009. Retrieved December 16, 2013, from http://www.jointcenter.org/sites/default/files/upload/research/files/The%20Economic%20Burden%20of%20Health%20Inequalities%20in%20the%20United%20States.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi JM, Margellos-Anast H, Whitman S. Black-White health disparities in the United States and Chicago: A 15-year progress analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:349–356. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. PL 111-148, secs. 5101, 5102, 5313, 5403, and 3509. 2010 Retrieved December 16, 2013, from http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/healthreform.

- Ransford HE, Carrillo FR, Rivera Y. Healthcare-seeking among Latino immigrants: Blocked access, use of traditional medicine, and the role of religion. Journal of Health Care for the Poor & Underserved. 2010;21:862–878. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal EL, editor. A summary of the National Community Health Advisor Study: Weaving the future (University of Arizona) Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona; 1998. Retrieved December 21, 2013 from http://www.chw-nec.org/pdf/CAHsummaryALL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Community Health Workers Evidence Based Models Toolbox. 2011 Retrieved December 16, 2013 from http://www.hrsa.gov/ruralhealth/pdf/chwtoolkit.pdf.

- Whitley EM, Everhart RM, Wright RA. Measuring return on investment of outreach by community health workers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006;17:6–15. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B, Morgana LC, Honeycutt AA, Thieda P, et al. Outcomes and costs of community health worker interventions: A systematic review. Medical Care. 2010;48(9):792–808. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35b51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]