Abstract

Objective

In clinical practice, behavioral approaches to obesity treatment focus heavily on diet and exercise recommendations. However, these approaches may not be effective for patients with disordered eating behaviors. Little is known about the prevalence of disordered eating behaviors in primary care patients with obesity or whether they affect difficulty making dietary changes.

Methods

We conducted a telephone interview of 337 primary care patients aged 18–65 years with BMI≥35kg/m2 in Greater-Boston, 2009–2011 (58% response rate, 69% women). We administered the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire R-18 (Scores 0–100) and the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-lite) (Scores 0–100). We measured difficulty making dietary changes using four questions regarding perceived difficulty changing diet (Scores 0–10).

Results

50% of patients reported high emotional eating (score>50) and 28% reported high uncontrolled eating (score>50). Women were more likely to report emotional [OR=4.14 (2.90, 5.92)] and uncontrolled eating [OR=2.11 (1.44, 3.08)] than men. African Americans were less likely than Caucasians to report emotional [OR=0.29 (95% CI: 0.19, 0.44)] and uncontrolled eating [OR=0.11 (0.07, 0.19)]. For every 10-point reduction in QOL score (IWQOL-lite), emotional and uncontrolled eating scores rose significantly by 7.82 and 5.48, respectively. Furthermore, participants who reported emotional and uncontrolled eating reported greater difficulty making dietary changes.

Conclusions

Disordered eating behaviors are prevalent among obese primary care patients and disproportionately affect women, Caucasians, and patients with poor QOL. These eating behaviors may impair patients' ability to make clinically recommended dietary changes. Clinicians should consider screening for disordered eating behaviors and tailoring obesity treatment accordingly.

Keywords: Disordered Eating, Obesity, Primary Care

Introduction

In clinical practice, behavioral approaches to obesity treatment focus heavily on diet and exercise recommendations.1 However, these approaches may not be as effective in patients with disordered eating behaviors including emotional and binge eating. Surprisingly, little is known about the prevalence of disordered eating behaviors in primary care patients with obesity and how they relate to dietary adherence.

Experts have characterized disordered eating behaviors into three domains: uncontrolled eating, emotional eating, and cognitive restraint.2 Uncontrolled eating, or a tendency to eat more than usual and a feeling of loss of control, is a defining characteristic of binge eating disorder (BED) which affects approximately 30% of obese patients seeking weight loss treatment.3 Emotional eating, or the tendency to eat in response to stress and emotions, is also associated with overweight and obesity.4–6 Cognitive restraint, or consciously restricting food intake to avoid gaining weight, can also be problematic due to overeating associated with excessive restriction.7–13

Recognizing disordered eating behaviors in primary care patients is important because these patients may do less well with traditional weight loss counseling approaches that do not address underlying psychological drivers of eating. Many of these patients use food as a coping mechanism to deal with life's stressors, yet clinical approaches generally focus on nutrition and exercise education and do not emphasize this major issue. Moreover, these disordered eating behaviors may affect whether patients are able to adhere to treatment and make clinically recommended dietary changes. Prior studies have examined disordered eating behaviors primarily in weight loss treatment seeking populations14–17 and community and convenience samples.2,6,8,11,18–21 However these populations may not be representative of general primary care settings due to selection based on treatment-seeking status and sample convenience.

Identifying primary care patients at high risk for disordered eating may help clinicians tailor treatment approaches, yet few studies have examined predictors of disordered eating. Quality of life (QOL), in particular, may be important to consider when evaluating a patient's underlying propensity for disordered eating. Patients with obesity commonly face social bias, often characterized by stigma, prejudice, and discrimination.22,23 This social bias can lead to social withdrawal, isolation, and lower QOL which may increase the likelihood a patient will use food as coping mechanism. Yet little research has examined how these psychosocial aspects of QOL relate to disordered eating.

In this context, we examined the prevalence of and factors associated with disordered eating behaviors in over 300 sociodemographically diverse primary care patients with moderate (Class II, 35.0 ≤ BMI< 39.9) to severe (Class III, BMI ≥ 40) obesity selected from four primary care clinics in the greater Boston area. Our aims were to 1) Determine the prevalence of disordered eating behaviors in primary care patients with obesity; 2) Identify clinical, demographic, and QOL factors associated with disordered eating; and 3) Examine whether these behaviors are adversely associated with patients' perceived difficulty making dietary changes that facilitate weight control.

Methods

Study Sample, Recruitment, and Data Collection

We performed a telephone interview of a representative random sample of patients with moderate to severe obesity (n=337) in 4 primary care practices in greater-Boston including a large hospital-based academic practice, a suburban practice in an affluent neighborhood, a practice in a working class community, and a community health center in a socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhood. Details of our study sample and sampling methods have been previously described.24 The primary aim of the parent study was to examine patient preferences and barriers regarding bariatric surgery. The current study is a secondary analysis of this parent study. Eligible patients were aged 18–65 years, had at least one visit in the practice in the preceding year, spoke English or Spanish, and had a body mass index (BMI) of 35 kg/m2 or higher (minimum eligibility criteria for bariatric surgery). We oversampled for African American and Hispanic patients and created sampling weights to adjust estimates to reflect the racial and ethnic distribution of practices from which patients were recruited. Patients without a valid address or telephone number and those with a terminal or serious life-limiting illness or severe unstable psychiatric illness (including one patient with an active eating disorder) were excluded. All telephone interviews were conducted in either English or Spanish by a trained interviewer and lasted approximately 45–60 minutes. Our response rate was approximately 58% of eligible patients.24 The study was approved by the local institutional review boards at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and University of Massachusetts.

Measures

Clinical and Demographic Factors

We asked about participants’ demographic characteristics including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education. In addition, we gathered information about patients’ chronic health conditions including health conditions associated with obesity. We calculated BMI (kg/m2) using self-reported height and weight.25

Eating Behaviors

We measured eating behaviors including uncontrolled eating, emotional eating, and cognitive restraint using the 18-item revised Three Factor Eating Questionnaire R-18 (TFEQ-R18).2 Respondents were asked to rate a series of statements about how often they engage in specific eating behaviors using a 4-point scale (definitely true, mostly true, mostly false, definitely false). Global scores for each eating behavior ranged from 0–100. Higher scores reflected higher levels of each eating behavior. Due to the lack of prior literature suggesting a cut point for this questionnaire, we chose to categorize TFEQ-R18 eating behavior domains as "high" based on an a priori cut point (Scores > 50) that captured those patients who responded "definitely true" or "mostly true" on more than 50% of the disordered eating questions.

Quality of Life

We assessed QOL using the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-lite (IWQOL-lite).26 The IWQOL-lite is a 31-item instrument developed to capture 5 domains specific to obesity including physical function, self-esteem, sexual life, public distress and work. Respondents were given a series of statements that begin with “Because of my weight…” and then asked to rate whether the statement is “always true, usually true, sometimes true, rarely true or never true.” A global score ranging from 0–100 is derived using standard methods.26 Higher scores reflect better QOL.

Difficulty Making Dietary Changes

We measured difficulty in making dietary changes using four questions regarding perceived difficulty changing certain aspects of diet that have been shown to facilitate weight loss.27–29 Specifically, respondents were asked to rate on a scale of 0–10, where 0 is not at all difficult and 10 is extremely difficult, how difficult it is to limit the 1) portion size, 2) total amount of calories, 3) fat in diet, and the 4) amount of carbohydrates (or "starches") in food. As one example, respondents were asked "…what number would you use to rate how difficult it is for you to limit the portion size of the food you eat?" Higher scores reflected greater difficulty making dietary changes. We categorized scores ≥ 7 as "high difficulty" in making dietary changes based on an equal division of the 10-point scale into low difficulty (0–3), moderate difficulty (4–6), and high difficulty (7–10).

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize demographic characteristics of the total sample and grouped by eating behavior (cognitive restraint, emotional eating, uncontrolled eating). To examine demographic and clinical predictors of disordered eating behaviors, we performed a series of multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models for each dichotomous eating behavior outcome (categorized as Scores ≤50 and Scores>50). We first adjusted for age (continuous), race, sex, BMI (<40, 40–44.99, >45), education and study site. We further adjusted for overall QOL and obesity-related comorbidities including heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, asthma, apnea, depression and anxiety. We used forward selection (p<0.10) and backward elimination (p<0.05) procedures to identify comorbid conditions significantly associated with the outcomes. To test the robustness of our findings, we conducted sensitive analyses to compare these estimates to multivariable-adjusted linear regression models for each eating behavior treated as a continuous outcome.

To explore the impact of QOL on eating behaviors, we modeled the relationship between overall QOL and specific domains of QOL (physical functioning, public distress, sex life, self-esteem, and work) on eating behaviors in separate linear regression models adjusted for age, race, sex, BMI, education, and study site. We compared adjusted R-squared values and linear regression coefficients to examine which QOL domain was the most important in predicting eating behaviors. Additionally, we examined the relative contributions of individual QOL domains using a series of linear regression models. Our first model included age, race, sex, BMI, education, and study site. We further adjusted for the QOL domain with the highest adjusted R-squared value and examined the marginal contribution above and beyond the first model. We compared the percent variation explained by this model to the amount of variation explained by subsequent models including each additional QOL domain. The order in which additional QOL factors were added to the model was based on adjusted R-squared values, from highest to lowest.

To examine the relationship between eating behaviors and perceived difficulty making dietary changes, we developed a series of multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models for difficulty decreasing portion sizes, calories, carbohydrates, and fats (Scores ≥7). Each outcome was included in a separate model. Eating behavior scores ≤ 50 were used as the reference category. We first adjusted for age, race, sex, BMI, education, and study site, then QOL, and finally comorbidities identified through model selection procedures.

We weighted all estimates to reflect the complex random sampling design. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

As shown in Table 1, the majority of patients were women. By design, more than half of the participants were Non-White, and a broad range of education and income levels were represented. The prevalence of disordered eating behaviors in the population was high; 50% of patients reported scores>50 for emotional eating (mean score=49.3) and 28% reported scores>50 for uncontrolled eating (mean score=38.0). More women reported high levels of emotional eating than men (p <0.0001). Similarly, Caucasians were more likely to report high emotional eating (p<0.0001) and uncontrolled eating (p<0.0001) then African-Americans or Hispanics. Obesity-related QOL scores varied by eating behavior. Participants who reported high emotional eating and uncontrolled eating also reported lower obesity-related QOL scores in all domains than those reporting lower levels of these eating behaviors. Emotional eating and uncontrolled eating were highly correlated; participants who reported high emotional eating were more likely to also report high uncontrolled eating (r = 0.42). High cognitive restraint was less correlated with high emotional eating (r =−0.10) and uncontrolled eating (r=−0.06) (data not shown).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics overall and by eating behavior

| Eating Behaviors1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=337) |

High

Cognitive Restraint (n=144) |

High Emotional Eating (n=164) |

High Uncontrolled Eating (n=91) |

|

| Mean age (yr) | 48.7 yr | 49.8 yr | 49.5 yr | 50.5 yr |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 40.7 kg/m2 | 41.2 kg/m2 | 41.6 kg/m2 | 41.8 kg/m2 |

| Sex | ||||

| Men, % | 31% | 30% | 22% | 28% |

| Women, % | 69% | 70% | 78% | 72% |

| Race | ||||

| White, % | 50% | 42% | 59% | 72% |

| African-American, % | 36% | 39% | 25% | 13% |

| Hispanic, % | 10% | 13% | 12% | 12% |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less, % | 36% | 37% | 31% | 38% |

| Some college or 2-yr degree, % | 29% | 30% | 29% | 25% |

| 4 yr college or more, % | 35% | 32% | 39% | 37% |

| Income | ||||

| $20,000 or less, % | 24% | 29% | 24% | 32% |

| $20,001–$40,000, % | 36% | 32% | 35% | 29% |

| $40,001–$80,000, % | 19% | 16% | 17% | 16% |

| over $80,000, % | 22% | 23% | 24% | 23% |

| IWQOL-Lite (0–100), mean scores | ||||

| Overall Summary | 70.3 | 71.0 | 60.6 | 57.9 |

| Physical Functioning | 61.9 | 60.3 | 54.3 | 51.8 |

| Self Esteem | 62.6 | 62.9 | 49.8 | 47.3 |

| Public Distress | 78.3 | 77.6 | 69.7 | 67.7 |

| Work | 82.5 | 83.4 | 74.9 | 72.8 |

| Sex Life | 77.1 | 77.9 | 66.9 | 63.3 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Cardio-/cerebrovascular disease, % | 5% | 3% | 4% | 6% |

| Asthma, sleep apnea, % | 35% | 40% | 41% | 43% |

| Depression, anxiety, % | 44% | 43% | 52% | 58% |

| Arthritis, back pain, % | 41% | 47% | 40% | 40% |

| Diabetes, % | 20% | 27% | 20% | 18% |

| High blood pressure, % | 50% | 58% | 51% | 46% |

| Other diseases2, % | 24% | 25% | 26% | 32% |

All results are based on a weighted sample.

Eating behavior scores >50 were categorized as 'high'.

Other diseases include gastroesophageal reflux disease, liver disease, and gall bladder problems.

Bolded results are significantly different (p<0.05) from results in those without high levels of disordered eating (scores <50).

Study Location: Greater Boston area. Time of data collection: 2009–2011.

In multivariable analyses adjusted for age, race, sex, BMI, education, study site and QOL (Table 2), women were significantly more likely to report high emotional and uncontrolled eating than men. In contrast, we observed no significant sex difference in cognitive restraint. With regard to differences by race/ethnicity, compared to Caucasians, African Americans were significantly less likely to report high emotional and uncontrolled eating. Similarly, Hispanics were also less likely to report high uncontrolled eating, although the difference was not statistically significant. Interestingly, both African Americans and Hispanics were significantly more likely to report cognitive restraint than Caucasians. Age did not appear to be a strong predictor of emotional and uncontrolled eating, however older participants were significantly more likely to report cognitive restraint.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical factors associated with eating behaviors

| Eating Behaviors1, OR (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Cognitive Restraint | High Emotional Eating | High Uncontrolled Eating | ||||

| Initial Model2 | Final Model3 | Initial Model | Final Model | Initial Model | Final Model | |

| Age (yrs) | 1.28 (1.11, 1.48)4 | 1.32 (1.13, 1.54) | 0.98(0.85, 1.14) | 0.86 (0.72, 1.14) | 1.14 (0.96, 1.34) | 1.15 (0.94, 1.40) |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 1.59 (1.06, 2.39) | 1.53(0.98, 2.40) | 0.29 (0.19,0.44) | 0.36 (0.21,0.60) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.19) | 0.16 (0.09, 0.29) |

| Hispanic | 2.68 (1.57, 4.58) | 2.51 (1.40,4.50) | 1.20 (0.69, 2.10) | 1.19 (0.61,2.32) | 0.60 (0.34,1.06) | 0.71 (0.38,1.36) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 0.88 (0.63,1.23) | 0.89 (0.62,1.29) | 4.14 (2.90, 5.92) | 3.64 (2.35,5.64) | 2.11 (1.44, 3.08) | 1.58 (1.02,2.47) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Less than 40 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 40–44.99 | 1.16 (0.80, 1.68) | 0.98 (0.66, 1.48) | 0.90 (0.61, 1.33) | 0.56 (0.35, 0.89) | 0.79 (0.51, 1.22) | 0.47 (0.28, 0.78) |

| 45 and up | 1.55 (1.06, 2.25) | 1.29 (0.82, 2.02) | 2.45 (1.61, 3.72) | 0.89(0.52, 1.55) | 1.68 (1.10, 2.56) | 0.73 (0.42, 1.25) |

| Education | ||||||

| High School or GED | 0.94 (0.63,1.41) | 0.99 (0.64,1.52) | 0.71 (0.46, 1.08) | 0.83 (0.51, 1.37) | 1.79 (1.12, 2.88) | 1.73 (1.01, 2.94) |

| 2-Year School | 1.22 (0.83, 1.80) | 1.23 (0.81, 1.86) | 0.95 (0.63, 1.42) | 1.14 (0.71, 1.82) | 1.14 (0.73, 1.80) | 1.25 (0.75, 2.08) |

| College or More | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

All results are based on a weighted sample.

Eating behavior scores >50 were categorized as 'high'.

Initial model adjusted for demographic variables including age, race, sex, BMI, education, and study site.

Final model was additionally adjusted for overall quality of life (QOL).

Values shown are adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Study Location: Greater Boston area. Time of data collection: 2009–2011.

In order to explore the relative effect of QOL on disordered eating, we examined multivariable-adjusted models with and without QOL (Table 2). Interestingly, before adjusting for QOL we observed that participants with BMI > 45 kg/m2 were significantly more likely to report disordered eating behaviors than those with BMI < 40 kg/m2, indicating that patients with more severe obesity are at higher risk for disordered eating. However, after adjustment for QOL we observed no significant association with BMI > 45, suggesting that QOL may explain the observed association between higher BMI and disordered eating. In sensitivity analyses, estimates from multivariable-adjusted models treating eating behaviors as continuous outcomes were similar (Table s1). General trends remained the same, however the relationship between sex and uncontrolled eating was not statistically significant.

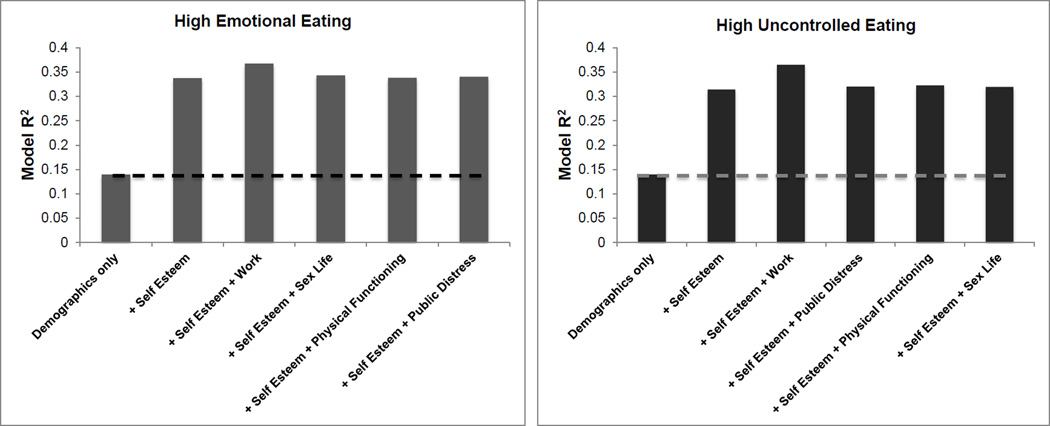

Table 3 presents model R-squared values and multivariable-adjusted associations between QOL domains and eating behaviors. QOL was not significantly associated with cognitive restraint, but lower QOL scores were significantly associated with higher scores on emotional eating and uncontrolled eating. Of the 5 QOL domains measured, higher scores on work function and self-esteem (better QOL) were the strongest correlates of less emotional and uncontrolled eating. In our examination of the relative contributions of individual QOL domains, the self-esteem domain explained more variation in emotional (R2 = 0.34) and uncontrolled eating (R2 = 0.31) than other QOL domains and more than doubled the explanatory power of the model. In post-hoc analyses, we examined the marginal contributions of individual QOL domains above and beyond demographic variables and self-esteem. Although the work domain slightly improved the explanatory power of the model, none of the domains were statistically significant once self-esteem was included in the model (Figure 1a–b).

Table 3.

Relationship between quality of life domains and eating behaviors

| Eating Behaviors (Scores 0–100) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Restraint | Emotional Eating | Uncontrolled Eating | |||||||

| R2 | β± SE1 | p-value | R2 | β± SE | p-value | R2 | β± SE | p-value | |

| QOL domains | |||||||||

| Overall | 0.04 | 0.75 ± 0.66 | 0.26 | 0.31 | −7.82 ± 0.95 | <0.0001 | 0.33 | −5.48 ± 0.68 | <0.0001 |

| Physical Functioning | 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.53 | 0.79 | 0.21 | −4.21 ± 0.83 | <0.0001 | 0.21 | −3.04 ± 0.60 | <0.0001 |

| Public Distress | 0.03 | 0.17 ± 0.55 | 0.76 | 0.21 | −4.35 ± 0.86 | <0.0001 | 0.21 | −3.38 ± 0.62 | <0.0001 |

| Sex Life | 0.03 | −0.03 ± 0.42 | 0.94 | 0.25 | −4.16 ± 0.64 | <0.0001 | 0.21 | −2.43 ± 0.47 | <0.0001 |

| Self Esteem | 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.44 | 0.61 | 0.34 | −6.06 ± 0.63 | <0.0001 | 0.31 | −4.15 ± 0.47 | <0.0001 |

| Work Dysfunction | 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.63 | 0.34 | 0.26 | −6.57 ± 0.95 | <0.0001 | 0.25 | −4.08 ± 0.70 | <0.0001 |

Quality of life domains were rescaled to reflect an increase in 10 units.

Estimates reflect the change in eating behavior score for each 10-unit increase in quality of life domain.

Models adjusted for demographic variables including age, race, sex, BMI, education, and study site.

Study Location: Greater Boston area. Time of data collection: 2009–2011.

Figure 1. Marginal contributions of individual quality of life domains explaining variation in disordered eating.

a–b. Scores >50 for emotional and uncontrolled eating were categorized as 'high.' Initial model (first bar) adjusted for age, race, sex, BMI, education, and study site. All subsequent models include the individual quality of life domains listed in addition to the variables in the first model. The area above the dashed line indicates the marginal contribution of the domains above and beyond the initial model.

Study Location: Greater Boston area. Time of data collection: 2009–2011

In analyses examining the relationship between disordered eating behaviors and difficulty making dietary changes (Table 4), participants who reported emotional and uncontrolled eating were significantly more likely to report difficulty (≥7 of 10 on difficulty scale) with reducing portion sizes, calories, carbohydrates, and fats. Although the strong positive association between uncontrolled eating and difficulty decreasing portion size and reducing calories was expected, high emotional and uncontrolled eaters also reported greater difficulty reducing carbohydrates and fats than those participants reporting lower levels of emotional and uncontrolled eating.

Table 4.

Relationship between eating behaviors and difficulty making dietary changes

| Difficulty making dietary changes (scores ≥ 7), OR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating Behaviors1 | Difficulty decreasing portion size |

Difficulty decreasing calories |

Difficulty decreasing carbohydrates |

Difficulty decreasing fats |

| High Cognitive Restraint | 1.11 (0.82, 1.51)2 | 0.70 (0.52, 0.94) | 0.54 (0.40, 0.74) | 0.90 (0.65, 1.23) |

| High Emotional Eating | 2.74 (2.00, 3.80) | 2.12 (1.55, 2.89) | 2.23 (1.62, 3.07) | 2.13 (1.52, 2.99) |

| High Uncontrolled Eating | 6.18 (4.26, 8.96) | 2.77 (1.95, 3.92) | 3.75 (2.58, 5.43) | 3.86 (2.69, 5.55) |

Eating behavior scores >50 were categorized as 'high'. Eating behavior scores ≤ 50 were used as reference.

Values shown are adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals).

Models adjusted for age, race, sex, BMI, education, and study site.

Study Location: Greater Boston area. Time of data collection: 2009–2011.

Discussion

In this study, we observed a high prevalence of disordered eating behaviors in primary care patients with moderate to severe obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2). Approximately half of patients reported high levels of emotional eating and more than a quarter reported uncontrolled eating. Women, Caucasians, and patients with poor QOL, particularly those with low self-esteem, were disproportionately affected. We also observed that high levels of emotional and uncontrolled eating were consistently associated with higher self-reported difficulty in making dietary changes including reducing portion sizes, calories, carbohydrates, and fats, even after accounting for demographic factors and BMI.

Our findings are in line with prior work showing that women generally report higher levels of emotional eating than men.6,8,21,30–32 Women are more susceptible to depression than men,33 and it may be that women are more likely to use food as a coping tool in response to negative affect. Also, consistent with prior studies, women were more likely to report uncontrolled eating.32,34,35 However, in contrast to prior work suggesting that women report higher levels of cognitive restraint,21,32,34,36 we did not observe a significant sex difference in cognitive restraint in our sample. This difference may be related to the lower mean BMI of prior studies (Mean BMI range: 21–28.8 kg/m2)21,32,34,36 compared with our sample (Mean BMI = 40.7 kg/m2). Our findings may also differ because, unlike in prior work, our estimates were adjusted for other demographic factors.

Little work has explored racial differences in eating behaviors. Our data suggest that African-Americans are less likely to report emotional eating and uncontrolled eating than Caucasians. This finding may reflect a true difference in eating behaviors across racial and ethnic groups or alternatively, or it may reflect a downward bias in reporting due to stigma around mental health issues in the African-American community.37 Compared with Caucasians, both African-Americans and Hispanics were more likely to report cognitive restraint independently of BMI. These interesting racial differences may be important to consider in the context of obesity treatment and merit exploration in future studies.

Our data suggest that higher BMI is associated with both emotional and uncontrolled eating, an expected finding consistent with prior work.4,6,11,34 Interestingly however, among those with BMI >45 this association substantially dissipated after adjusting for QOL, suggesting that poor QOL was a stronger correlate of disordered eating behavior than BMI alone and likely mediates the association between BMI and disordered eating. Literature on the relation between BMI and cognitive restraint is inconsistent.5–8,18,34 The question of whether high cognitive restraint and restriction of food intake leads to overeating and weight gain or alternatively, that overweight and obese individuals are simply more likely to be dieting and therefore report high cognitive restraint, cannot be teased out by cross-sectional data.6,18 We observed higher cognitive restraint scores among those with a higher BMI, but we cannot infer temporality or causality based on this cross-sectional data.

In a finding not previously reported, our study suggests that patients with higher levels of emotional and uncontrolled eating report greater difficulty in making dietary changes including decreasing portion sizes, calories, carbohydrates, and fats. This finding has important implications for the clinical treatment of obesity. Traditional behavioral treatment approaches focus heavily on diet and exercise recommendations. However, these approaches may not be effective in patients reporting high levels of emotional and uncontrolled eating. Our data suggest these patients find making prescribed dietary changes challenging. This may be, in part, because many of these patients use food as a coping mechanism to deal with life's stressors. Given the high prevalence of these eating behaviors in primary care, clinicians should consider tailoring weight loss treatment to address these emotional factors affecting eating. Strategies that focus on stress reduction and improved coping skills such as mindfulness may be a promising approach to integrate into clinical obesity treatment, particularly to address emotional and binge eating.38

There are several limitations to our study. Study participants were recruited from four Boston-area primary care clinics so our results are not generalizable outside this geographic area. All study measures were self-reported via phone survey, so it is possible there was under-reporting on BMI and eating behaviors. Also, the survey instrument we used to measure difficulty making dietary changes has not been formally tested for reliability and validity. Although our cross-sectional study design precludes us from making causal inferences, our findings regarding the prevalence of disordered eating behaviors and association with perceived difficulty making dietary changes retain clinical importance. Lastly, our modest sample size may have limited our power to detect small but clinically important differences.

This study suggests that disordered eating behaviors including emotional and uncontrolled eating are prevalent among primary care patients with obesity. Women, Caucasians and patients with poor QOL, particularly those with low self-esteem, are disproportionately affected. Moreover, these eating behaviors may impair patients' ability to make clinically recommended dietary changes. Primary care clinicians should consider screening for disordered eating especially among those at highest risk and tailor weight loss treatment to address psychological and emotional drivers of eating.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK073302, PI Wee). Dr. Wee is supported by a NIH Midcareer Mentorship Award (K24DK087932). Dr. Chacko is supported by an Institutional National Research Service Award (T32AT000051), the Ryoichi Sasakawa Fellowship Fund, and the Division of General Medicine and Primary Care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Portions of this paper were presented at the annual meeting of The Obesity Society in Atlanta, GA on November 15, 2013 and the Society for General Internal Medicine meeting in San Diego, CA on April 24, 2014.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Authorship: Dr. Wee designed the parent study, obtained funding, and supervised the conduct of the study. Drs. Wee and Chacko conceived the research question. Ms. Chiodi has full access to all of the data in the study, conducted all analyses, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Chacko drafted the initial manuscript, and Dr. Wee and Ms. Chiodi provided critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Carter FA, Jansen A. Improving psychological treatment for obesity. Which eating behaviours should we target? Appetite. 2012;58:1063–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlsson J, Persson LO, Sjostrom L, Sullivan M. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) in obese men and women. Results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1715–1725. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL. Epidemiology of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34(Suppl):S19–S29. doi: 10.1002/eat.10202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozier AD, Kendrick OW, Leeper JD, Knol LL, Perko M, Burnham J. Overweight and obesity are associated with emotion- and stress-related eating as measured by the eating and appraisal due to emotions and stress questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, Gerber RA, et al. Psychometric analysis of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R21: results from a large diverse sample of obese and non-obese participants. International Journal of Obesity. 2009;33:611–620. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peneau S, Menard E, Mejean C, Bellisle F, Hercberg S. Sex and dieting modify the association between emotional eating and weight status. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2013;97:1307–1313. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.054916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Swain RM, Stunkard AJ, Platte P, Vogt RA. The Eating Inventory in obese women: clinical correlates and relationship to weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:778–785. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Lauzon-Guillain B, Basdevant A, Romon M, Karlsson J, Borys JM, Charles MA. Is restrained eating a risk factor for weight gain in a general population? Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:132–138. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lluch A, Herbeth B, Mejean L, Siest G. Dietary intakes, eating style and overweight in the Stanislas Family Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1493–1499. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beiseigel JM, Nickols-Richardson SM. Cognitive eating restraint scores are associated with body fatness but not with other measures of dieting in women. Appetite. 2004;43:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindroos AK, Lissner L, Mathiassen ME, et al. Dietary intake in relation to restrained eating, disinhibition, and hunger in obese and nonobese Swedish women. Obes Res. 1997;5:175–182. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawson OJ, Williamson DA, Champagne CM, et al. The association of body weight, dietary intake, and energy expenditure with dietary restraint and disinhibition. Obes Res. 1995;3:153–161. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herman CP, Mack D. Restrained and unrestrained eating. J Pers. 1975;43:647–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1975.tb00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.d'Amore A, Massignan C, Montera P, Moles A, De Lorenzo A, Scucchi S. Relationship between dietary restraint, binge eating, and leptin in obese women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:373–377. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gradaschi R, Noli G, Cornicelli M, Camerini G, Scopinaro N, Adami GF. Do clinical and behavioural correlates of obese patients seeking bariatric surgery differ from those of individuals involved in conservative weight loss programme? J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;26(Suppl 1):34–38. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gianini LM, White MA, Masheb RM. Eating pathology, emotion regulation, and emotional overeating in obese adults with Binge Eating Disorder. Eat Behav. 2013;14:309–313. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boschi V, Iorio D, Margiotta N, D'Orsi P, Falconi C. The three-factor eating questionnaire in the evaluation of eating behaviour in subjects seeking participation in a dietotherapy programme. Ann Nutr Metab. 2001;45:72–77. doi: 10.1159/000046709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angle S, Engblom J, Eriksson T, et al. Three factor eating questionnaire-R18 as a measure of cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating in a sample of young Finnish females. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geliebter A, Aversa A. Emotional eating in overweight, normal weight, and underweight individuals. Eat Behav. 2003;3:341–347. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(02)00100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldschmidt AB, Crosby RD, Engel SG, et al. Affect and eating behavior in obese adults with and without elevated depression symptoms. The International journal of eating disorders. 2013;47(3):281–286. doi: 10.1002/eat.22188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keskitalo K, Tuorila H, Spector TD, et al. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire, body mass index, and responses to sweet and salty fatty foods: a twin study of genetic and environmental associations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:263–271. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Psychosocial origins of obesity stigma: toward changing a powerful and pervasive bias. Obes Rev. 2003;4:213–227. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2003.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Hout GC, van Oudheusden I, van Heck GL. Psychological profile of the morbidly obese. Obes Surg. 2004;14:579–588. doi: 10.1381/096089204323093336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wee CC, Huskey KW, Bolcic-Jankovic D, Colten ME, Davis RB, Hamel M. Sex, race, and consideration of bariatric surgery among primary care patients with moderate to severe obesity. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:68–75. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2603-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9:102–111. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen SD, Kang J, Kline GA. Portion control plate for weight loss in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a controlled clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1277–1283. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bazzano LA, Hu T, Reynolds K, et al. Effects of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:309–318. doi: 10.7326/M14-0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, Selker HP, Schaefer EJ. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. Jama. 2005;293:43–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsen JK, van Strien T, Eisinga R, Engels RC. Gender differences in the association between alexithymia and emotional eating in obese individuals. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.French SA, Jeffery RW, Wing RR. Food intake and physical activity: a comparison of three measures of dieting. Addict Behav. 1994;19:401–409. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Provencher V, Drapeau V, Tremblay A, Despres JP, Lemieux S. Eating behaviors and indexes of body composition in men and women from the Quebec family study. Obes Res. 2003;11:783–792. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bebbington PE. Sex and depression. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aurelie L, Gilles F, Jean-Jacques D, et al. Characterization of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire scores of a young French cohort. Appetite. 2012;59:385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bellisle F, Dalix AM. Cognitive restraint can be offset by distraction, leading to increased meal intake in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:197–200. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Lauzon B, Romon M, Deschamps V, et al. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R18 is able to distinguish among different eating patterns in a general population. The Journal of nutrition. 2004;134:2372–2380. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ward EC, Wiltshire JC, Detry MA, Brown RL. African American men and women's attitude toward mental illness, perceptions of stigma, and preferred coping behaviors. Nurs Res. 2013;62:185–194. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31827bf533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katterman SN, Kleinman BM, Hood MM, Nackers LM, Corsica JA. Mindfulness meditation as an intervention for binge eating, emotional eating, and weight loss: a systematic review. Eat Behav. 2014;15:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.