Abstract

Three iron-sulfur proteins–HydE, HydF, and HydG–play a key role in the synthesis of the [2Fe]H component of the catalytic H-cluster of FeFe hydrogenase. The radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine enzyme HydG lyses free tyrosine to produce p-cresol and the CO and CN− ligands of the [2Fe]H cluster. Here, we applied stopped-flow Fourier transform infrared and electron-nuclear double resonance spectroscopies to probe the formation of HydG-bound Fe-containing species bearing CO and CN− ligands with spectroscopic signatures that evolve on the 1- to 1000-second time scale. Through study of the 13C, 15N, and 57Fe isotopologs of these intermediates and products, we identify the final HydG-bound species as an organometallic Fe(CO)2(CN) synthon that is ultimately transferred to apohydrogenase to form the [2Fe]H component of the H-cluster.

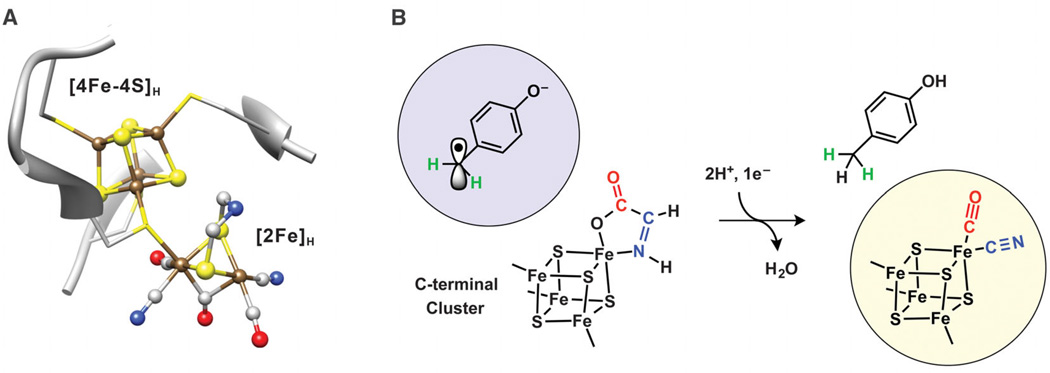

FeFe hydrogenase enzymes rapidly evolve H2 at a 6-Fe catalytic site termed the H-cluster (Fig. 1A) (1–3), which comprises a traditional 4Fe-4S subcluster ([4Fe-4S]H), produced by canonical Fe-S cluster biosynthesis proteins, that is linked via a cysteine bridge to a dinuclear Fe subcluster ([2Fe]H) that contains unusual ligands. Specifically, the [2Fe]H subcluster possesses two terminal CN− ligands, two terminal CO ligands, and azadithiolate and CO bridges, all of which are thought to be synthesized and installed by a set of Fe-S proteins denoted HydE, HydF, and HydG. In one recent model for the [2Fe]H center bioassembly pathway (4, 5), the two radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) enzymes of the set, HydE and HydG, generate the dithiolate moiety and free CO and CN−, respectively, and these ligands are then transferred to a dinuclear Fe precursor bound to HydF, which acts as a scaffold protein for assembling the final [2Fe]H subunit. Individually expressed HydE, HydF, and HydG can be combined for successful in vitro synthesis of the [2Fe]H component of the H-cluster and concurrent activation of FeFe hydrogenase apoprotein (6, 7). Alternatively, an abiotically synthesized dinuclear Fe subcluster, constructed with an azadithiolate bridge as well as one CN− and two CO ligands per Fe, can also be used to activate FeFe hydrogenase (8, 9).

Fig. 1. Ligand synthesis by HydG.

(A) The catalytic H-cluster of FeFe hydrogenases. Ball-and-stick representation (from Protein Data Bank entry 3C8Y) was generated by using University of California San Francisco Chimera: Fe (brown), S (yellow), C (gray), O (red), and N (blue). H was not shown for simplicity. (B) Proposed HydG-catalyzed conversion of 4Fe-4S–bound dehydroglycine to an Fe(CO)(CN) species concomitant with conversion of 4OB• to p-cresol (17).

The HydG radical SAM enzyme was previously reported to use free l-tyrosine (Tyr) as its substrate to generate p-cresol and free CO and CN− as its products (6, 10–12). Although HydG has yet to be crystallographically characterized, sequence analysis and results from spectroscopic studies indicate that it has two 4Fe-4S clusters, each with distinct functions (13, 14). The SAM-binding 4Fe-4S cluster, located near the N terminus, reductively cleaves SAM, producing methionine plus a strongly oxidizing 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical (5′-dA•) (15, 16). The second Fe-S cluster, located near the C terminus, was implicated as the site of Tyr binding in our recent investigation of the HydG reaction mechanism using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy (17). Also on the basis of EPR spectroscopic results, we proposed that the initial 5′-dA• generates a neutral tyrosine radical bound to this C-terminal 4Fe-4S cluster, which then undergoes heterolytic cleavage at the Cα-Cβ bond, forming a 4-oxidobenzyl radical (4OB•) and cluster-bound dehydroglycine (DHG) (Fig. 1B) (17). Electron and proton transfer to the 4OB• radical then yields the p-cresol product concomitant with the scission of DHG to form Fe-bound CO and CN− and water (Fig. 1B). In this report, we explored the subsequent time course of the HydG reaction by using stopped-flow Fourier transform infrared (SF-FTIR) and electron-nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) spectroscopies to follow the synthesis of Fe(CO)x(CN)y species and track them to the completion of the H-cluster bioassembly pathway.

SF-FTIR is a useful time-resolved method for studying the HydG reaction mechanism because CO and CN− ligands give rise to strong infrared absorption bands with energies and intensities sensitive to the coordination and electronic environment of the bound Fe center. Figure 2 summarizes SF-FTIR data after the reaction of wild-type Shewanella oneidensis HydG (HydGWT) with excess substrates SAM and 13C-labeled Tyr [(13C)9-Tyr] in the presence of the reductant sodium dithionite (DTH). Observed bands are assigned to stretch vibrations of CO and CN ligands on the basis of their energy shifts upon 12C:13C and 14N:15N site-specific isotope substitution (fig. S2), which was achieved through use of the appropriate Tyr isotopologs (6). The time evolution of the resultant spectra (Fig. 2, A to C) reveals a stepwise conversion of a discrete intermediate, which we term complex A, to a distinct new species, complex B. Complex A is characterized by two bands at 1906 cm−1 and 2048 cm−1 [1949 cm−1 and 2093 cm−1 with 12C-Tyr (Fig. 2D)], which we assign to stretching modes arising from terminal Fe-13CO and Fe-13CN moieties, respectively. The kinetic profile (Fig. 2B) shows that complex A accumulates on the same time scale as the decay of the previously observed 4OB• (17). Hence, the FTIR spectrum and formation kinetics of complex A are consistent with the mechanistic model in Fig. 1B, with the first turnover of HydG, SAM, and Tyr forming bound CO and CN−, presumably on the unique Fe site of the C-terminal 4Fe-4S cluster. Complex A does not form in the relatively conservative Cys394→Ser394 (C394S), C397S HydG double mutant (HydGSxxS), which lacks the C-terminal cluster (figs. S3 and S4).

Fig. 2. FTIR spectra.

Reactions used 100 µM HydGWT and (13C)9-Tyr, producing 13CO and 13CN ligands, unless indicated otherwise. (A) SF-FTIR spectra measured at 30 and 1200 s (solid lines) and at 10 s using 800 µM HydGWT (dotted line, plotted at half intensity). (B) Time dependence of formation and decay of the following species: 4OB• determined by EPR spectroscopy, two experimental runs (•, °) and corresponding kinetic fit (dashed line) (17); FTIR data (no kinetic fit) of complex A (red) and complex B (blue) determined by the peak heights of their respective ν(CO) modes [see (A)]; and free CO trapped by myoglobin (green) (fig. S3). Each data set is scaled to unity at its maximum value. (C) Comparison of the time dependence of the peak heights of all ν(CO) and ν(CN) bands for complex A and complex B. Complex A red symbols are as follows: °, ν(13CN); •, ν(13CO). Complex B blue symbols are as follows: °, ν(13CN); •, ν(13CO) 2010 cm−1; +, ν(13CO) 1960 cm−1. The data for complex A were taken from measurements by using 800 µM HydGWT in order to enhance the signal:noise ratio of the ν(CN) mode. (D) Table of frequencies for observed IR bands of complexes A and B prepared by using Tyr (middle column) or (13C)9-Tyr (right-most column). (E) SF-FTIR spectrum of complex B measured at 900 s and prepared by using a 1:1 mixture of Tyr and 13COO-Tyr (top). Average of the 12CO and 13CO product B spectra (bottom). The arrows indicate new bands not present in either the 12CO or 13CO spectra of complex B. (F) SF-FTIR spectra of complex B measured at 1200 s and prepared by using (13C)9 15N-Tyr (top) and (13C)9Tyr (bottom). Expected (CN) and (CO) bands for 13C15N-containing complex B in the absence of ν(CN)/ ν(CO) vibrational mixing (dotted line). Predicted band shifts computed simply by the change in the reduced mass.

Complex A reaches a maximum concentration and starts to decay after about 30 s, concomitant with the appearance and growth of complex B. The three bands associated with complex B have identical kinetics and may be assigned to terminal bound ligands: two high-energy, predominately ν(13CO) modes at 1960 cm−1 and 2010 cm−1 and a ν(13CN) mode at 2062 cm−1. We assign the 2010 cm−1 band to a predominantly ν(13CO) mode rather than a ν(13CN) mode because its energy shifts upon 13C isotopic substitution at the carboxyl position in Tyr [the moiety that gives rise to the CO but not the CN ligands in the mature H cluster (fig. S2)] (6). An additional band at 1906 cm−1 and shoulder at 2048 cm−1 likely arise from residual complex A.

A reasonable structure for complex B is a cuboidal Fe(CO)2(CN)-[3Fe-4S] species in which the unique Fe site is coordinated by the three Tyr-derived diatomic ligands. For CO and CN− ligands that are bound to a single Fe center, the ν(CO) and ν(CN) vibrational modes are expected to be strongly coupled. To test for vibrational mixing between the two observed ν(CO) frequencies, we generated a 1:2:1 mixture of 12CO12CO-, 12CO13CO-, and 13CO13CO-labeled complex B from a 1:1 mixture of natural abundance Tyr and 13COO-Tyr. If the two ν(CO) modes in complex B were not coupled, then the expected resulting spectrum would be a simple 1:1 superposition of the 12CO12CO and 13CO13CO spectra (Fig. 2E, lower trace). Instead, the observed spectrum displayed overlapping additional bands (Fig. 2E, upper trace) that can be ascribed to the two 12CO13CO-labeled isotopomers with apparent CO-stretching frequencies shifted relative to their isotopically pure counterparts because of vibrational mixing of the two fundamental ν(CO) modes (fig. S6). Similarly, a comparison of spectra generated by using (13C)9-Tyr and (13C)9 15N-Tyr (Fig. 2F) shows that 15N substitution produces both a smaller than expected energy shift in the ν(CN) mode as well as an energy shift in the higher energy ν(CO) mode, indicating that these modes are also vibrationally mixed. Taken together, these coupling data suggest that all three ligands (two CO and one CN−) in complex B are bound to a single Fe-center.

The relatively high energies of the ν(CO) modes of complex B suggest that it may be appropriately modeled as a cationic, low-spin [Fe(II)(CO)2(CN)]+ complex based on comparisons with related neutral, low-spin Fe(II)(CO)2(CN) complexes (18, 19). The density functional theory (DFT)–calculated ν(CO) and ν(CN) frequencies and intensities of [fac-(H2S)3Fe(II)(CO)2(CN)]+, a simple model for {Fe(II)(CO)2(CN)-[3Fe-4S]}+, show reasonable agreement with the observed spectrum of complex B (fig. S5 and table S2). Alternative stereoisomers in which the CO and CN− ligands are not cofacial or in which the sulfur donors are replaced with oxygen donors were not found to give rise to the expected intensity patterns. In addition, the coupling pattern in the 12CO13CO isotope mixture (Fig. 2E, top) was only reproduced computationally when the two CO ligands have different inherent ν(CO) energies, which could be explained by the electronic asymmetry of the coordinating [3Fe-4S]0 subcluster (20) or by asymmetry in CO H-bonding interactions.

The kinetics in Fig. 2B suggest sequential conversion of complex A to complex B, which we associate with another turnover of HydG acting on a second substrate Tyr to form an additional CO to coordinate the unique Fe center of the C-terminal cluster (21). Unlike the first turnover (17), we have no experimental information at this time about how Tyr binds and what intermediates may be involved in this second reaction, although we note that our model for complex A is coordinatively unsaturated and could bind Tyr or a Tyr-derived fragment during the second turnover. Only at much longer times was free CO detected in solution through its binding to exogenous myoglobin (see green trace in Fig. 2B and fig. S3), which rules out the binding of externally derived CO as part of the mechanism. The release of free CO is correlated with the rise of complex A (Fig. 2B) at a late time (>300 s), suggesting that complex B may degrade to complex A by loss of CO when other H-cluster maturation components are not available to facilitate its incorporation into the proper downstream assembly products (vide infra). Reports of no lag phase in free CO production (12) may arise from alternative chemistry resulting from differences in experimental protocols.

To determine the fate of the Fe-containing complex B, we measured the continuous-wave (CW) EPR and pulse ENDOR spectra of HydA1 hydrogenase from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii that had been either uniformly or selectively labeled with 57Fe [xxxxx (I) = 1 or 2]. Uniformly 57Fe-labeled HydA1 (HydA157Fe) was generated by introducing 57Fe into the growth media for HydA1. The Q-band Davies pulse ENDOR (22) spectrum of the purified HydA157Fe poised in the Hox state is shown in Fig. 3A. This spectrum was obtained at the highest xxxxxx (g) value, g1 = 2.10, where there is no overlap with the EPR signal from the CO-inhibited Hox-CO form (fig. S7), and it shows several peaks in the 3- to 10-MHz range.

Fig. 3. Q-band (34.00 GHz, 1.155 T) Davies ENDOR spectra of FeFe hydrogenase HydA1 enriched with 57Fe.

(A) HydA157Fe; (B) HydA157Fe–HydG [black, experiment; red, simulation with A(57Fe) = 16.0 MHz]; (C) (A) – (B) difference spectrum [black, experiment; red, simulation with A(57Fe) = 10.55 MHz]. ENDOR simulations used line widths of 0.4 and 0.65 MHz for [2Fe]H and [4Fe-4S]H components, respectively, with other values taken directly from experiment parameters and CW EPR simulations. The ENDOR spectrum of natural abundance Fe HydA1 in the Hox state was subtracted from both spectra (A) and (B). a.u., arbitrary units.

For a sample of HydA1 (that we term HydA157Fe–HydG) in which the [2Fe]H cluster was assembled in vitro (6, 7) by using HydE and HydF expressed in natural abundance media and HydG expressed in 57Fe-enriched media (fig. S1), the ENDOR spectrum (Fig. 3B) was well simulated by a single doublet, with frequencies ν± = A(57Fe)/2 ± νI, where A(57Fe) = 16.0 MHz is the effective hyperfine tensor component at this g1 = 2.10 value and νI is the 57Fe nuclear Zeeman frequency at this magnetic field. We assigned this doublet to the [2Fe]H subcluster, because the [4Fe-4S]H cluster is not labeled with 57Fe for this sample. Subtraction of the 57Fe ENDOR spectrum of the [2Fe]H subcluster–labeled sample from that of the HydA157Fe sample isolated the 57Fe ENDOR signal that arose from the [4Fe-4S]H cluster (Fig. 3C), which was well simulated as an ENDOR doublet with A(57Fe) = 10.55 MHz. Both A(57Fe) values for HydA1 are consistent with previous ENDOR and Mössbauer spectroscopic studies of the Hox state of Desulfovibrio vulgaris and Clostridium pasteurianum hydrogenases (≈16 to 18 MHz for the [2Fe]H subcluster and ≈ 8 to 10MHz for the [4Fe-4S]H cluster) (23–26), although they differ somewhat from those derived from ENDOR data for the Desulfovibrio desulfuricans hydrogenase (12.4 and 11.1 MHz, respectively) (27). Comparing the magnitudes of the two A(57Fe) values determined above confirms that the greatest spin density of the H-cluster in the Hox state lies on the [2Fe]H subcluster. More importantly, these ENDOR data show that Fe in the [2Fe]H subcluster of the mature H-cluster originates from the HydG radical SAM maturase.

The SF-FTIR and 57Fe ENDOR spectroscopic results presented in this report provide further insight into the assembly of the [2Fe]H subcluster of FeFe hydrogenase, illustrated in Fig. 4. Prior work demonstrated that the CO and CN− ligands of the [2Fe]H subcluster are generated from Tyr via HydG. Results from SFFTIR spectroscopic studies provide evidence for the formation of two distinct Fe-bound CO and CN-containing species, complexes A and B, during the HydG reaction. Analysis of the vibrational mode coupling buttressed by DFT results on realistic model complexes lead us to postulate that complex B is a 3Fe-4S–bound Fe(CO)2(CN) species. The 57Fe-labeling experiments prove that Fe in the [2Fe]H subcluster is provided by HydG. It is therefore straightforward to envisage a mechanism wherein two complex B units assemble together with a dithiolate bridge to form the [2Fe]H cluster. Our proposal for the structure of this deliverable species is consistent with all of the available data and points to the biologically relevant product of the HydG reaction as being an organometallic Fe(CO)2(CN) synthon.

Fig. 4. Schematic for the bioassembly of the FeFe hydrogenase H-cluster via a HydG-synthesized Fe(CO)2(CN) synthon.

Pink indicates xxxxx; cyan, xxxxx; gray, xxxxxxxx.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the NIH (R.D.B., no GM072623; S.P.C., no. GM65440) and by the Division of Material Sciences and Engineering (J.R.S., award no. DE-FG02-09ER46632) of the Office of Basic Energy Sciences (OBER) of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), by DOE OBER (S.P.C.), and the UniCat Cluster of Excellence of the German Research Council (V.P.).

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

www.sciencemag.org/content/343/6169/[page]/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S10

Tables S1 and S2

References (27–43)

References and Notes

- 1.Vignais PM, Billoud B. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4206–4272. doi: 10.1021/cr050196r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent KA, Parkin A, Armstrong FA. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4366–4413. doi: 10.1021/cr050191u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams MWW, Stiefel EI. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2000;4:214–220. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shepard EM, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:10448–10453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001937107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulder DW, et al. Structure. 2011;19:1038–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuchenreuther JM, George SJ, Grady-Smith CS, Cramer SP, Swartz JR. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e20346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuchenreuther JM, Britt RD, Swartz JR. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e45850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berggren G, et al. Nature. 2013;499:66–69. doi: 10.1038/nature12239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esselborn J, et al. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9:607–609. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pilet E, et al. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:506–511. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Driesener RC, et al. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:1687–1690. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shepard EM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:9247–9249. doi: 10.1021/ja1012273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubach JK, Brazzolotto X, Gaillard J, Fontecave M. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5055–5060. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tron C, et al. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011;2011:1121–1127. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frey PA, Hegeman AD, Ruzicka FJ. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008;43:63–88. doi: 10.1080/10409230701829169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vey JL, Drennan CL. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:2487–2506. doi: 10.1021/cr9002616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuchenreuther JM, et al. Science. 2013;342:472–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1241859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piper TS, Cotton FA, Wilkinson G, Inorg J. Nucl. Chem. 1955;1:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darensbourg DJ. Inorg. Chem. 1972;11:1606–1609. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weigel JA, Holm RH, Surerus KK, Munck E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:9246–9247. [Google Scholar]

- 21.This process would also entail formal loss of CN−. Although the SF-FTIR data for complex B cannot rigorously exclude coordination by two CN− groups, we consider this to be unlikely because only one n(CN) mode is observed and only one CN− per Fe is present in both the assembled [2Fe]H subcluster and the synthetic dinuclear Fe compound that can activate the FeFe hydrogenase (8, 9)

- 22.Davies ER. Phys. Lett. A. 1974;47:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Telser J, Benecky MJ, Adams MWW, Mortenson LE, Hoffman BM. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:13536–13541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Telser J, Benecky MJ, Adams MWW, Mortenson LE, Hoffman BM. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:6589–6594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popescu CV, Munck E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:7877–7884. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira AS, Tavares P, Moura I, Moura JJG, Huynh BH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:2771–2782. doi: 10.1021/ja003176+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.