Abstract

This survey study compared pre- and post-pandemic knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and intended behaviors of pregnant women regarding influenza vaccination (seasonal and/or pandemic) during pregnancy in order to determine key factors influencing their decision to adhere to influenza vaccine recommendations. Only 36% of 662 pre-pandemic respondents knew that influenza was more severe in pregnant women, compared to 62% of the 159 post-pandemic respondents. Of the pre-pandemic respondents, 41% agreed or strongly agreed that that it was safer to wait until after the first 3 months to receive the seasonal influenza vaccine, whereas 23% of the post-pandemic cohort agreed or strongly agreed; 32% of pre-pandemic participants compared to 11% of post-pandemic respondents felt it was best to avoid all vaccines while pregnant. Despite 61% of the pre-pandemic cohort stating that they would have the vaccine while pregnant if their doctor recommended it and 54% citing their doctor/nurse as their primary source of vaccine information, only 20% said their doctor discussed influenza vaccination during their pregnancy, compared to 77% of the post-pandemic respondents who reported having this conversation. Women whose doctors discussed influenza vaccine during pregnancy had higher overall knowledge scores (P < 0.0001; P = 0.005) and were more likely to believe the vaccine is safe in all stages of pregnancy (P < 0.0001; P = 0.001) than those whose doctors did not discuss influenza vaccination. The 2009 H1N1 pandemic experience appeared to change attitudes and behaviours of health care providers and their pregnant patients toward influenza vaccination.

Keywords: attitudes and behaviors, H1N1 pandemic, influenza vaccine, pregnancy, survey

Multiple studies have demonstrated that pregnant women infected with influenza virus experience excess morbidity and mortality when compared with other groups.1-4 One study, based on Canadian hospital admissions from 1994 to 2000, found that healthy pregnant women 20 to 34 years old were almost 18 times more likely to be hospitalized for influenza-related illness than non-pregnant women of the same age.5 Influenza vaccination during pregnancy is safe at all stages of pregnancy and while breastfeeding.6-8 In light of such evidence, national advisory bodies recommend the inclusion of all pregnant women at any stage of pregnancy among high-priority recipients of influenza vaccine and the World Health Organization recommended that pregnant women be the highest priority for influenza vaccination.1,4,9

Pregnant women were at increased risk for more severe disease and complications due to the pandemic H1N1 infection.10-12 From April 12, 2009 to April 3, 2010, during the 2 waves of the pandemic, there were 1300 hospitalizations, 257 intensive care unit admissions, and 50 deaths of women of child-bearing age (15–44 years) due to laboratory-confirmed pandemic H1N1 influenza reported in Canada.13 Of these women, 266 (20.5%) were pregnant, leading to a hospitalization rate of 91.7 per 100,000 compared to 16.5 per 100,000 among non-pregnant women of childbearing age.13 All 4 pregnant women who died were in their third trimester and all occurred during the first wave of the pandemic. Similarly, in the first 4 months of the pandemic, the US reported a 5-fold increase in the recent yearly average death rate for pregnancy from seasonal influenza, a trend which was reflected worldwide.14,15 As a result, pregnant women were identified as a high-priority group for vaccination and were the focus of targeted communication efforts to receive the vaccine throughout the pandemic.

H1N1 vaccine uptake among pregnant women exceeded the historical uptake rates (approximately 15%) of seasonal influenza immunization among pregnant women in Canada and the US.16,17 Seasonal influenza vaccination rates also increased during the pandemic and the trend continued through the 2010–2011 influenza seasons.18 However, the rates have dropped again in subsequent seasons and remain well below the recommended Healthy People 2020 target of 80%.19,20

Achieving high influenza vaccine coverage rates in pregnant women continues to be important especially given that the 2009 pandemic H1N1 strain continues to circulate and is now included in the seasonal influenza vaccine.13,21 Although data on the perceptions of pregnant women regarding influenza vaccination before and during the pandemic are informative, an understanding of the views of this population post-pandemic is critical to the development of effective influenza vaccination promotion campaigns designed to maintain high levels of influenza vaccine coverage. The aim of this study was to explore and compare pre-and post-pandemic knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and intended behaviors (KABB) of pregnant women regarding influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Understanding how the pandemic influenced pregnant women's acceptance of the H1N1 vaccine may provide insight into the specific drivers that determine pregnant women's decision to adhere to influenza vaccination recommendations.

Results

Demographics

Subject characteristics

A total of 662 pre-pandemic and 159 post-pandemic surveys were completed. The majority of women were aged 25–34 years; were “Caucasian” (white); and had completed a postsecondary or advanced (MA, MD, PhD) degree. In both surveys, approximately one-fifth of participants were health care providers (Table 1). A total of 41% of pre-pandemic participants and 36% of post-pandemic participants were primiparous; approximately one-third of women in both groups were pregnant for a second time, whereas 26% of the pre-pandemic group and 30% of the post-pandemic cohort had been pregnant at least twice before. The mean gestation at the time of completion for the pre-pandemic group was 27.7 weeks and for the post-pandemic group was 27.2 weeks. Approximately 33% of the pre-pandemic survey participants and 24% of post-pandemic participants had attended at least one prenatal class during their current pregnancy. Twenty-nine percent of pre-pandemic participants and 49% of post-pandemic participant reported receiving the majority of their care during their current pregnancy from a family doctor/general practitioner whereas 60% and 42%, respectively, were cared for mainly by obstetricians. Of the surveyed women who reported one main source for their vaccine information, more than half cited their doctor/nurse as their primary source. A total of 10% of women in the pre-pandemic cohort and 4% in the post-pandemic group reported never having received information about vaccines.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents

| Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 662 | N = 159 | P-value | |

| Age (Years) | |||

| Under 18 | 3 (0.5) | 4 (2.5) | 0.001 |

| 18–24 | 67 (10.1) | 16 (10.1) | |

| 25–34 | 435 (65.7) | 85 (53.5) | |

| 35–44 | 157 (23.7) | 53 (33.3) | |

| 45 or older | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 25 (3.8) | 7 (4.4) | 0.226 |

| Completed high school | 44 (6.6) | 13 (8.2) | |

| Some post-secondary | 131 (19.8) | 24 (15.1) | |

| Completed post-secondary | 377 (56.9) | 85 (53.5) | |

| Advanced degree | 85 (12.8) | 30 (18.9) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 628 (94.9) | 141 (88.7) | 0.026 |

| Black | 9 (1.4) | 3 (1.9) | |

| Asian | 6 (0.9) | 5 (3.1) | |

| First Nations or Inuit | 7 (1.1) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Other | 12 (1.8) | 8 (5.0) | |

| Number of pregnancies | |||

| 1 | 271 (40.9) | 57(35.85) | 0.592 |

| 2 | 218 (32.9) | 54(33.96) | |

| 3 | 95 (14.4) | 27(16.98) | |

| 4 | 46 (6.9) | 10(6.29) | |

| >4 | 31 (4.7) | 11(6.92) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 0(0.0) | |

| Health care provider | |||

| Yes | 125 (18.9) | 32 (20.1) | 0.74 |

| No | 534 (80.7) | 127 (79.9) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.5) | ||

| Number of weeks pregnant | |||

| Mean | 27.7 | 27.2 | 0.5 |

| SD | 0.34 | 9.36 | |

| Range | 6-41 | 0-41 | |

| Attended pre-natal class | |||

| Yes | 218 (32.9) | 38 (23.9) | 0.052 |

| No | 443 (66.9) | 120 (75.5) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Physician considers pregnancy high risk | |||

| Yes | 133 (20.1) | 37 (23.3) | 0.329 |

| No | 473 (71.5) | 114 (71.7) | |

| Don't know | 54 (8.2) | 7 (4.4) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Primary care provider | |||

| Family doctor / general practitioner | 192 (29.0) | 78 (49.1) | <0.0001 |

| Obstetrician | 399 (60.3) | 67 (42.1) | |

| Family doctor / General Practitioner & obstetrician | 27 (4.1) | 7 (4.4) | |

| Other | 31 (4.7) | 4 (2.5) | |

| Don't know | 7 (1.1) | ||

| Unknown | 6 (0.9) | 3 (1.9) | |

| At least one pre-existing condition* | |||

| Yes | 238 (36.0) | 39 (24.5) | 0.006 |

| No | 424 (64.0) | 120 (75.5) | |

| Diagnosed with asthma | |||

| Yes | 115 (17.4) | 32 (20.1) | 0.109 |

| No | 544 (82.2) | 124 (78.0) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.5) | 3 (1.9) | |

| Primary source of information about vaccines | |||

| Doctor/nurse | 356 (53.8) | 85 (53.5) | 0.0003 |

| Media | 79 (11.9) | 15 (9.4) | |

| Internet | 15 (2.3) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Never received any information | 65 (9.8) | 6 (3.8) | |

| Other | 61 (9.2) | 9 (5.7) | |

| Several sources† | 83 (12.5) | 42 (26.4) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.5) | ||

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | |||

| Yes | 129 (19.5) | 123 (77.4) | <0.0001 |

| No | 530 (80.1) | 36 (22.6) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Ever received influenza vaccine | |||

| Yes | 374 (56.5) | 132 (83.0) | <0.0001 |

| No | 282 (42.6) | 27 (17.0) | |

| Unknown | 6 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Received influenza vaccine every year | |||

| Yes | 180 (48.1) | 72 (45.3) | <0.0001 |

| No | 192 (51.3) | 74 (46.5) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0.5) | 13 (8.2) | |

*For influenza immunization, pre-existing indications include chronic cardio-pulmonary diseases, immunocompromised status, and high-risk contacts. These pre-existing indications include heart condition, cystic fibrosis, asthma, other lung condition(s), allergy to eggs, allergic reaction to previous influenza vaccination, and Guillain-Barré syndrome. The pre-existing indications donot include high blood pressure, diabetes, abnormalities of the cervix or uterus, autoimmune disease, and liver disease hepatitis.

†includes respondents who report more than one of doctor/nurse, media, internet, or other sources of vaccine information.

Risk factors during pregnancy

More than one-third of participants in pre-pandemic surveys reported having at least one pre-existing health condition, whereas approximately 25% of participants in the post-pandemic group reported having at least one pre-existing health condition, with asthma being the one most frequently cited (17% [115/662]) and 20% [32/159], respectively). Advanced maternal age (≥35 years) was a risk factor for 24% and 34%, respectively, of women surveyed. Only 20% of the pre-pandemic cohort and 23% of the post-pandemic participants reported that their physician considered their pregnancy to be high-risk.

Reported immunization behavior

Seasonal influenza

Nearly half of respondents (48% [180/662]) and 45% [72/159] pre- and post-pandemic, respectively) reported receiving influenza vaccine every year. Of those pregnant women who reported receiving the vaccine every year, 37% (n = 66) of the pre-pandemic cohort and 29% (n = 21) of the post-pandemic cohort were health care workers. A total of 20% of pre-pandemic participants reported that their doctor discussed the influenza vaccine with them during this pregnancy, whereas 77% reported that their doctor had discussed seasonal influenza vaccination during pregnancy with them. When asked the main reason for receiving the seasonal influenza vaccine in the past, 44% of pre-pandemic participants and 45% of post-pandemic participants who gave a single response cited protection against disease for self and family, whereas 19% of pre-pandemic participants and 38% of the post pandemic cohort cited their doctor's recommendation. When asked the main reason for not receiving the seasonal influenza vaccine in the past, 36% of the pre-pandemic participants and 70% of post-pandemic women thought they did not need it, whereas 5% and 26%, respectively, were concerned about side effects and 27% and 44%, reported they had no specific reason.

Pandemic influenza

A total of 67% of the post-pandemic respondents reported having received the pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine. Those who routinely receive seasonal influenza vaccine were more likely to have received the pandemic vaccine (90.3% vs. 50.0%, P < 0.001). The main reason for receiving the pandemic vaccine cited by 48% (51/106) of women was to protect themselves, their children, and/or family from infection. Almost one-fifth of these women (20% [21/106]) cited their nurse or doctor's recommendation as the main reason for receiving the pandemic vaccine. Other reasons provided for receiving the pandemic vaccine included: requirement of employer (health care worker or otherwise; n = 3) and pregnancy (n = 1). Among the women who did not receive the H1N1 pandemic vaccine, 26% (13/50) reasoned that they did not think they needed it and 14% (7/50) were concerned about potential side effects. Three women did not receive the pandemic vaccine because they thought the vaccine was brought to market too quickly.

H1N1 pandemic experience

Just over half of post-pandemic respondents (53% [82/155]) reported that they themselves, their close family or friends, extended family, and/or co-worker became infected with H1N1 influenza during the pandemic. Of the women who reported one main source of information on the H1N1 pandemic (n = 109), 51% (56/109) relied primarily on the media, 18% (20/109) relied on their doctor or nurse, and 11% (12/109) relied on Health Canada. The most common ‘other’ source cited was work.

Knowledge and attitudes

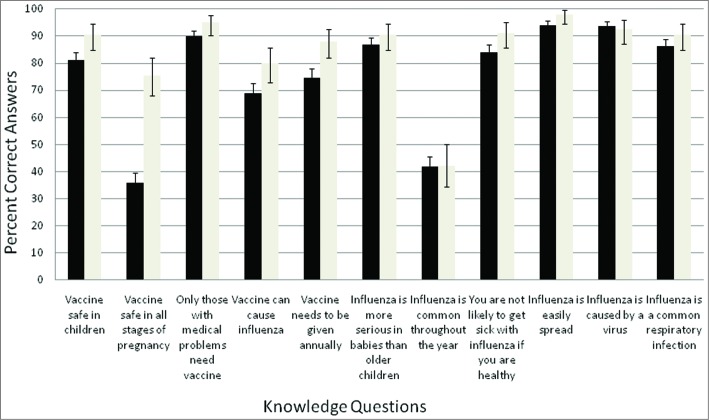

The majority of participants in both groups answered the knowledge questions correctly (Fig. 1). A total of 75% (494/662) of pre-pandemic participants and 88% (140/159) of post-pandemic participants knew the vaccine needed to be given annually but 29% and 18%, respectively, believed that the seasonal influenza vaccine could cause influenza. Only 36% of pre-pandemic participants agreed that influenza was more severe in pregnant women, compared to 62% of post-pandemic participants.

Figure 1.

Proportion of respondents correctly answering knowledge-based questions. Black bars are pre-pandemic and white bars post-pandemic; error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Almost half of pre-pandemic participants (49% [95% CI 45.1–52.8]) did not think the seasonal vaccine was safe in all stages of pregnancy, compared to 18.2% [95% CI 12.6–25.1]) of post-pandemic participants. Almost all (94%) post-pandemic participants knew that Canada's National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) recommends that all pregnant women receive the seasonal influenza vaccine. Forty-one percent (95% CI 37.6–45.2) of pre-pandemic participants agreed or strongly agreed that it was safer to wait until after the first 3 months to receive the seasonal influenza vaccine, whereas 23% (95% CI 16.9–30.6) of the post-pandemic cohort agreed or strongly agreed with that statement. Thirty-two percent (95% CI 28.3-35.6) of pre-pandemic participants compared to 11% (95% CI 6.8–17.3) of post-pandemic participants felt it was best to avoid all vaccinations while pregnant. Being a health care worker did not change this perception.

Sixteen percent (95% CI 13.4–19.2) of pre-pandemic respondents and 42% (95% CI 33.8–49.6) of post-pandemic respondents agreed or strongly agreed that giving the seasonal influenza vaccine to pregnant women will help protect newborn babies from getting influenza, whereas 49% (95% CI 44.8–52.5) and 73% (95% CI 65.3–79.7) of participants, respectively, believed that parents should receive the seasonal influenza vaccine to prevent passing influenza to their babies.

Pre-pandemic, mean knowledge scores were associated with age, level of education, being a health care provider, physician considering pregnancy high risk, source of vaccine information, primary care provider, whether one's physician discussed vaccination during pregnancy, and annual receipt of influenza vaccine (Table 2). Post-pandemic, knowledge scores were associated with being a health care provider, source of vaccine information, whether one's physician discussed vaccination during pregnancy, and annual receipt of influenza vaccine. Both pre- and post-pandemic, those who agreed or strongly agreed that it is best to avoid all vaccines while pregnant, that it is safer to wait until after the first 3 months to receive the vaccine, and that healthy pregnant women do not require influenza vaccine had lower overall knowledge scores compared to those who disagreed or strongly disagreed. Pre- and post-pandemic participants who reported that their physician discussed influenza vaccination during pregnancy had higher overall knowledge scores (9.2 vs. 8.2, P < 0.0001; 9.6 vs. 8.6, P = 0.005, respectively, Table 2) and were more likely to believe the vaccine is safe in all stages of pregnancy (66.4% vs. 33.6%, P < 0.0001; 85.0% vs. 15.0%, P = 0.001. respectively) than those whose doctors did not discuss influenza vaccination. Participants in both groups who reported receiving influenza vaccine annually had higher overall knowledge scores than those who do not routinely receive the vaccine (9.2 vs. 8.1, P < 0.0001; 9.8 vs. 9.1, P < 0.004), were more likely to believe the vaccine is safe in all stages of pregnancy (64.6% vs. 35.4%, P < .0001; 86.1% vs. 11.1%, P = 0.031), and tended to disagree more with the statement that it is best to avoid all vaccines while pregnant (58.2% vs. 24.6%, P < .0001; 90.3% vs. 60.8% P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Mean of knowledge score corresponding to demographic characteristics of survey respondents

| Pre-pandemic n | Post-pandemic n | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 662 | P-value | N = 159 | P-value | |

| Age (Years) | ||||

| Under 18 | 8.000 | 0.014 | 9.250 | 0.275 |

| 18–24 | 7.791 | 8.750 | ||

| 25–34 | 8.510 | 9.294 | ||

| 35–44 | 8.248 | 9.566 | ||

| 45 or older | 0.000 | 11.00 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 7.280 | <0.0001 | 8.857 | 0.233 |

| Completed high school | 7.999 | 8.692 | ||

| Some post-secondary | 7.886 | 9.083 | ||

| Completed post-secondary | 8.448 | 9.447 | ||

| Advanced degree | 9.306 | 9.633 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 8.400 | 0.206 | 9.433 | 0.055 |

| Black | 7.778 | 7.667 | ||

| Asian | 7.833 | 9.200 | ||

| First Nations or Inuit | 7.000 | 10.000 | ||

| Other | 8.500 | 8.250 | ||

| Number of pregnancies | ||||

| 1 | 8.221 | 0.433 | 9.459 | 0.948 |

| 2 | 8.486 | 9.222 | ||

| 3 | 8.568 | 9.407 | ||

| 4 | 8.370 | 8.9 | ||

| >4 | 7.886 | 9.793 | ||

| Unknown | 10.500 | 10.000 | ||

| Health care provider | ||||

| Yes | 9.312 | <0.0001 | 10.063 | 0.002 |

| No | 8.150 | 9.158 | ||

| Attended pre-natal class | ||||

| Yes | 8.211 | 0.103 | 9.526 | 0.396 |

| No | 8.452 | 9.292 | ||

| Physician considers pregnancy high risk | ||||

| Yes | 8.399 | 0.031 | 9.487 | 0.763 |

| No | 8.433 | 9.281 | ||

| Don't know | 7.759 | 9.286 | ||

| Primary care provider | ||||

| Family doctor / general practitioner | 8.385 | <0.0001 | 9.410 | |

| Obstetrician | 8.419 | 9.194 | ||

| Family doctor / general practitioner & obstetrician | 8.524 | 10.333 | ||

| Other | 7.368 | 9.750 | ||

| Don't know | 6.286 | 0.000 | ||

| Primary source of information about vaccines | ||||

| Doctor/nurse | 8.357 | <0.0001 | 9.306 | 0.003 |

| Media | 8.2025 | 9.267 | ||

| Internet | 8.800 | 8.500 | ||

| Never received any information | 7.508 | 8.167 | ||

| Other | 9.131 | 10.111 | ||

| Several sources† | 8.546 | 9.069 | ||

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 9.225 | <0.0001 | 9.553 | 0.005 |

| No | 8.162 | 8.611 | ||

| Received influenza vaccine every year | ||||

| Yes | 9.174 | <0.0001 | 9.764 | 0.004 |

| No | 8.085 | 9.108 | ||

†includes respondents who report more than one of doctor/nurse, media, internet, or other sources of vaccine information.

In the multivariate logistic regression of the pre-pandemic survey, being a health care provider, education level, having one's doctor discuss influenza vaccination, and receiving influenza vaccine previously or annually correlated most frequently with correct answers to the knowledge questions (Table 4), whereas a doctor discussion and previous influenza vaccination correlated most frequently with pro-vaccination attitudes (Table 5). Post-pandemic, having a doctor discuss influenza vaccination correlated most frequently with correct responses, and annual receipt of influenza vaccine correlated most frequently with positive attitudes toward influenza vaccination.

Table 3:

Distribution of responses to attitude questions by demographic characteristics of survey respondents

| Health care provider | It is best to avoid all vaccinations while pregnant | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude question 1: | |||||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 60 (48.0) | 0.008 | 26 (81.3) | 0.105 |

| Neither | 27 (21.6) | 3 (9.4) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 37 (29.6) | 3 (9.4) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 163 (30.5) | 86 (67.7) | ||

| Neither | 187 (35.0) | 26 (20.5) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 174 (32.6) | 15 (11.8) | |||

| Attended Prenatal Class | It is best to avoid all vaccinations while pregnant | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 77 (35.3) | 0.857 | 29 (76.3) | 0.355 |

| Neither | 67 (30.7) | 5 (13.2) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 71 (32.6) | 4 (10.5) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 147 (33.2) | 83 (69.2) | ||

| Neither | 148 (33.4) | 24 (20.0) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 140 (31.6) | 13 (10.8) | |||

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | It is best to avoid all vaccinations while pregnant | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 82 (63.6) | <0.0001 | 100 (81.3) | <0.0001 |

| Neither | 22 (17.1) | 16 (13.0) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 24 (18.6) | 7 (5.7) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 141 (26.6) | 12 (33.3) | ||

| Neither | 192 (36.2) | 13 (36.1) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 187 (35.3) | 11 (30.6) | |||

| Received influenza vaccine every year | It is best to avoid all vaccinations while pregnant | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 107 (58.2) | <0.0001 | 65 (90.3) | <0.0001 |

| Neither | 51 (27.7) | 5 (6.9) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 24 (13.0) | 2 (2.8) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 113 (24.6) | 45 (60.8) | ||

| Neither | 158 (34.4) | 18 (14.3) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 180 (39.2) | 11 (14.9) | |||

| Attitude question 2: | |||||

| Health care provider | Pregnant women are at higher risk of severe illness from seasonal influenza than women who are not pregnant | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 47 (37.6) | 0.165 | 5 (15.6) | 0.753 |

| Neither | 35 (28.0) | 4 (12.5) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 41 (32.8) | 23 (71.9) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 162 (30.3) | 25 (19.7) | ||

| Neither | 163 (30.5) | 26 (20.5) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 197 (36.9) | 76 (59.8) | |||

| Attended Prenatal Class | Pregnant women are at higher risk of severe illness from seasonal influenza than women who are not pregnant | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 58 (26.6) | 0.003 | 6 (15.8) | 0.999 |

| Neither | 58 (26.6) | 6 (15.8) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 97 (44.5) | 26 (68.4) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 152 (34.3) | 24 (20.0) | ||

| Neither | 140 (31.6) | 24 (20.0) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 142 (32.1) | 72 (60.0) | |||

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | Pregnant women are at higher risk of severe illness from seasonal influenza than women who are not pregnant | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 43 (33.3) | 0.904 | 25 (20.3) | 0.541 |

| Neither | 35 (27.1) | 23 (18.7) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 50 (38.8) | 75 (61.0) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 165 (31.1) | 5 (13.9) | ||

| Neither | 163 (30.8) | 7 (19.4) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 189 (35.7) | 24 (66.7) | |||

| Received influenza vaccine every year | Pregnant women are at higher risk of severe illness from seasonal influenza than women who are not pregnant | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 59 (32.1) | 0.977 | 10 (13.9) | 0.403 |

| Neither | 56 (30.4) | 11 (15.3) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 68 (37.0) | 51 (70.8) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 145 (31.6) | 19 (25.7) | ||

| Neither | 136 (29.6) | 14 (18.9) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 166 (36.2) | 41 (55.4) | |||

| Attitude question 3: | |||||

| Health care provider | It is safer to wait until after the first 3 months of pregnancy to receive a seasonal influenza vaccine | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 32 (25.6) | 0.088 | 20 (62.5) | 0.005 |

| Neither | 42 (33.6) | 8 (25.0) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 50 (40.0) | 4 (12.5) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 72 (13.5) | 41 (32.3) | ||

| Neither | 228 (42.7) | 53 (41.7) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 222 (41.6) | 33 (26.0) | |||

| Attended Prenatal Class | It is safer to wait until after the first 3 months of pregnancy to receive a seasonal influenza vaccine | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 32 (14.7) | 0.017 | 15 (39.5) | 0.532 |

| Neither | 75 (34.4) | 12 (31.6) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 107 (49.1) | 11 (28.9) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 71 (16.0) | 46 (38.3) | ||

| Neither | 196 (44.2) | 49 (40.8) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 167 (37.7) | 25 (20.8) | |||

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | It is safer to wait until after the first 3 months of pregnancy to receive a seasonal influenza vaccine | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 37 (28.7) | 0.001 | 54 (43.9) | 0.035 |

| Neither | 46 (35.7) | 44 (35.8) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 45 (34.9) | 25 (20.3) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 67 (12.6) | 7 (19.4) | ||

| Neither | 225 (42.5) | 17 (47.2) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 226 (42.6) | 12 (33.3) | |||

| Received influenza vaccine every year | It is safer to wait until after the first 3 months of pregnancy to receive a seasonal influenza vaccine | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 49 (26.6) | 0.005 | 37 (51.4) | 0.128 |

| Neither | 64 (34.8) | 24 (33.3) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 70 (38.0) | 11 (15.3) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 54 (11.8) | 24 (32.4) | ||

| Neither | 200 (43.6) | 26 (35.1) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 194 (42.3) | 24 (32.4) | |||

| Attitude question 4: | |||||

| Health care provider | Healthy pregnant women do not require the seasonal influenza vaccine. | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 65 (52.0) | 0.011 | 25 (78.1) | 0.566 |

| Neither | 35 (28.0) | 3 (9.4) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 24 (19.2) | 4 (12.5) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 205 (38.4) | 94 (74.0) | ||

| Neither | 188 (35.2) | 19 (15.0) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 131 (24.5) | 14 (11.0) | |||

| Attended Prenatal Class | Healthy pregnant women do not require the seasonal influenza vaccine. | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 101 (46.3) | 0.286 | 25 (65.8) | 0.083 |

| Neither | 60 (27.5) | 9 (23.7) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 54 (24.8) | 4 (10.5) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 171 (38.6) | 94 (78.3) | ||

| Neither | 163 (36.8) | 12 (10.0) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 101 (22.8) | 14 (11.7) | |||

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | Healthy pregnant women do not require the seasonal influenza vaccine. | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 88 (68.2) | <0.0001 | 99 (80.5) | 0.004 |

| Neither | 30 (23.3) | 13 (10.6) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 10 (7.8) | 11 (8.9) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 183 (34.5) | 20 (55.6) | ||

| Neither | 193 (36.4) | 9 (25.0) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 144 (27.2) | 7 (19.4) | |||

| Received influenza vaccine every year | Healthy pregnant women do not require the seasonal influenza vaccine. | Pre-pandemic n (%) | Post-pandemic n (%) | ||

| n = 662 | p-value | N = 159 | p-value | ||

| Yes | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 126 (68.5) | <0.0001 | 68 (94.4) | <0.0001 |

| Neither | 40 (21.7) | 2 (2.8) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 17 (9.2) | 2 (2.8) | |||

| No | Strongly Disagree / Disagree | 142 (30.9) | 46 (62.2) | ||

| Neither | 176 (38.3) | 15 (20.3) | |||

| Strongly Agree / Agree | 132 (28.8) | 13 (17.3) | |||

Table 4:

Selected variables associated with P-value for each knowledge binary response in multivariate logistic regression analysis

| Pre-pandemic Selected Variables | p-value | Post-pandemic Selected Variables | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza is a common respiratory infection which causes symptoms such as cough, fever and sore muscles. | Attended pre-natal Class | 0.0313 | None | None |

| Received influenza Vaccine Every year | 0.0416 | |||

| Influenza is caused by a virus | Number of Weeks Pregnant | 0.0065 | None | None |

| Health care Provider | 0.0269 | |||

| Physician considers pregnancy high risk | 0.0316 | |||

| Diagnosed with asthma | 0.0003 | |||

| Influenza infection is easily spread from person to person | Ever received influenza vaccine | 0.0023 | None | None |

| You are not likely to get sick with influenza if you are healthy | None | None | None | None |

| Influenza is common throughout the year | Education | 0.0001 | Education | 0.0451 |

| Health care provider | <.0001 | Number of weeks pregnancy | 0.0036 | |

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | 0.0309 | Attended pre-natal class | 0.0018 | |

| Physician considers pregnancy high risk | 0.0106 | |||

| Health care provider | 0.0021 | |||

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | 0.0132 | |||

| Influenza infection is more serious in babies than in older children | Ever received influenza vaccine | 0.0155 | Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | 0.025 |

| Influenza vaccine needs to be given every year | Health care provider | 0.0142 | Ever received influenza vaccine | 0.0034 |

| Received influenza vaccine every year | <.0001 | |||

| Influenza vaccine can cause influenza | Education | 0.035 | Education | 0.0072 |

| Health care provider | 0.0001 | |||

| Ever received influenza vaccine | 0.0046 | |||

| Only people with medical problems need to get influenza vaccine. | Ever received influenza vaccine | 0.0059 | None | None |

| Influenza vaccine is safe in all stages of pregnancy | Age | 0.0296 | Diagnosed with asthma | 0.0438 |

| Education | 0.0049 | Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | 0.0004 | |

| Number of pregnancies | 0.0083 | |||

| Health care provider | 0.0001 | |||

| Attended pre-natal class | 0.0086 | |||

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | <.0001 | |||

| Received influenza vaccine every year | <.0001 | |||

| Influenza vaccine is safe in children | Age | 0.0076 | Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | 0.0002 |

| Education | 0.0032 | |||

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | 0.0103 | |||

| Received influenza vaccine ever year | 0.0030 |

* For influenza immunization, pre-existing indications include chronic cardio-pulmonary diseases, immunocompromised status, and high-risk contacts. These pre-existing conditions include: heart condition, cystic fibrosis, asthma, other lung condition(s), allergy to eggs, allergic reaction to previous influenza vaccination, and Guillain-Barré syndrome. The pre-existing conditions do not include, high blood pressure, diabetes, abnormalities of the cervix or uterus, autoimmune disease, and liver disease or hepatitis.

Table 5:

Selected variables associated with P-value for each attitude ordinal response in multivariate logistic regression analysis

| Pre-pandemic Selected Variables | p-value | Post-pandemic Selected Variables | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| It is best to avoid all vaccinations while pregnant. | Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | <.0001 | Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | <.0001 |

| Ever received influenza vaccine | Received influenza | <.0001 | ||

| Received influenza vaccine every year | <.0001 | Vaccine every year | ||

| Pregnant women are at higher risk of severe illness from influenza than women who are not pregnant | Education | 0.0024 | None | None |

| Race | 0.0383 | |||

| Attended pre-natal | 0.0008 | |||

| class | ||||

| It is safer to wait until after the first 3 months of pregnancy to receive an influenza vaccine | Attended pre-natal class | 0.0088 | Education | 0.0018 |

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | 0.0008 | Physician considers Pregnancy high risk | 0.0105 | |

| At least one pre-existing condition* | 0.0462 | At least one Pre-existing condition* | 0.0103 | |

| Received influenza vaccine ever year | 0.0094 | |||

| Healthy pregnant women do not require influenza vaccine | Doctor ever discussed vaccination during pregnancy | <.0001 | Received influenza vaccine ever year | <.0001 |

| Received influenza vaccine every year | <.0001 | |||

| Pregnant women who receive influenza vaccine are more likely to experience side effects from the vaccine than women who are not pregnant | Education | 0.0305 | Race | 0.0169 |

| Health care provider | 0.0161 | Health care provider | 0.0132 | |

| Doctor ever discussed vaccine during pregnancy | <.0001 | Received influenza vaccine ever year | 0.0028 | |

| Ever received influenza vaccine | 0.0047 | |||

| Received influenza vaccine every year | 0.0006 | |||

| Giving influenza vaccine to pregnant women will help protect newborn babies from getting influenza | Primary source of information about vaccines | 0.0092 | None | None |

| Influenza vaccine poses greater risk to healthy children than natural influenza infection | Education | <.0001 | Race | 0.0361 |

| Primary source of Information about | 0.0070 | Health care provider | 0.0127 | |

| Doctor ever discussed vaccine during pregnancy | <.0001 | Received influenza vaccine ever year | 0.0025 | |

| Received influenza vaccine every year | 0.04 | |||

| It is important that all children in the household are vaccinated against influenza to protect new born babies | Age | 0.0234 | Received influenza vaccine ever year | 0.0106 |

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination | 0.0036 | |||

| Ever received influenza vaccine | 0.027 | |||

| Received influenza vaccine ever year | 0.0001 | |||

| Parents should receive influenza vaccine to prevent passing influenza onto their babies | Age | 0.0201 | Doctor ever discussed vaccine during pregnancy | 0.0280 |

| Doctor ever discussed vaccination | 0.0027 | Received influenza vaccine ever year | <.0001 | |

| Ever received influenza vaccine | 0.0290 | |||

| Received influenza vaccine ever year | <.0001 | |||

| If a vaccine is recommended for all children by the National Advisory Committee on Immunization(part of public Health Agency of Canada that makes recommendation on vaccines) the government has a responsibility to pay for the vaccine for all children | Race | 0.0493 | Received influenza vaccine ever year | 0.0002 |

*For influenza immunization, pre-existing indications include chronic cardio-pulmonary diseases, immunocompromised status, and high-risk contacts. These pre-existing conditions include: heart condition, cystic fibrosis, asthma, other lung condition(s), allergy to eggs, allergic reaction to previous influenza vaccination, and Guillain-Barré syndrome. The pre-existing conditions do not include: high blood pressure, diabetes, abnormalities of the cervix or uterus, autoimmune disease, and liver disease or hepatitis.

Pandemic H1N1 influenza

More than half of the respondents (56% [88/156]) incorrectly thought that the pandemic H1N1 influenza virus was a new strain of influenza; however, most respondents (78% [119/153]) knew that the pandemic virus caused more severe illness in pregnant woman than the seasonal flu typically did. A large proportion of respondents (42% [64/152]) incorrectly thought that more people died from pandemic influenza infections than die from seasonal influenza each year although 69% of respondents were aware that young healthy individuals were affected more severely by the pandemic influenza than by seasonal influenza.

The majority of respondents (61% [94/155]) were ‘slightly worried’ about the H1N1 influenza pandemic whereas 25% (38/155) were ‘not worried’ and 15% (23/155) were ‘very worried’. Almost half (49% [75/154]) of the respondents surveyed considered H1N1 pandemic influenza infection in pregnant women to be ‘very severe’, the other half (49% [75/154]) of respondents considered it to be ‘somewhat severe’, and a minority considered it to be ‘not severe’ (2.6% [4/154]). Respondents who believed the pandemic to be severe, and who were worried about it were more likely to change their opinion and receive the seasonal influenza vaccine, as well as have a more favorable opinion on immunization in general.

Intended immunization behavior

Sixty-one percent (404/662) of pre-pandemic respondents stated that they would have the seasonal influenza vaccine during pregnancy if their doctor recommended it, whereas 80% (126/158) of post-pandemic women surveyed reported that they would receive the seasonal influenza vaccine during pregnancy if their doctor said it was safe and recommended. For the respondents who are more likely to get the seasonal influenza vaccine after living through the H1N1 pandemic, the 2 most common reasons cited were concern about their own safety during pregnancy (36% [28/77]) and concern about the safety of their children/family (30% [23/77]). Twenty-nine percent (45/155) of participants reported after witnessing the pandemic that they were more likely to immunize themselves and their children. The most common reason cited by women who were less likely to receive the seasonal influenza vaccine after the pandemic was that they were not affected by the H1N1 pandemic and so they are not concerned about seasonal influenza (45% [14/31]). Almost one-fifth (19% [6/31]) of respondents reasoned that because they had already received the pandemic H1N1vaccine they would be protected against the next seasonal influenza and therefore were less likely to get the seasonal vaccine.

Discussion

Before the H1N1 2009 pandemic, vaccine uptake rates in this “at-risk” population remained disconcertingly low despite pregnant women being identified as a priority group for vaccination. In Nova Scotia, vaccine coverage with the 2009 H1N1 pandemic vaccine was 54% in the general population 6 months of age and older and 64% in pregnant women.22 Our surveys, comparing pre- and post-pandemic cohorts, demonstrate a shift in knowledge and attitudes during and immediately following the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1), consistent with other studies reporting trends in vaccine uptake among pregnant women following the pandemic.13,19,23,24 Almost twice as many of the post-pandemic cohort knew that seasonal flu was more severe in pregnant women, and they were also aware that the pandemic virus caused more severe illness in pregnant women than the seasonal flu virus. Attitudes also seemed significantly affected by the experience of living through the pandemic. There was not as much concern about vaccine safety among the post-pandemic cohort, and there was more feeling that the vaccine would help protect newborns and that parents should receive the vaccine to prevent passing the virus to their children. In the context of the pandemic, significantly more women reported that their physician discussed influenza with them during their pregnancy, indicating perhaps increased awareness of the risk to pregnant women among health care providers. As with the pre-pandemic cohort, women whose doctors discussed influenza vaccination during pregnancy were more knowledgeable and more accepting of the vaccine in any stage of pregnancy. However, whereas 61% of pre-pandemic respondents stated that they would receive the influenza vaccine while pregnant if their doctor recommended it, with only 20% reporting that their doctor had actually discussed influenza vaccination during their pregnancy, the margin was much narrower for the post-pandemic group, with 80% reporting they would receive the vaccine if their doctor recommended it and 77% reporting that their doctor did discuss it with them. This increase in discourse about the vaccine between women and their providers is a significant finding given that health care provider recommendation has emerged repeatedly in the literature as a key factor contributing to acceptance of vaccine by pregnant women.20,25 Schindler et al26 describe a zone of indecision, a gray zone, between 2 nuanced positions, which manifest in hesitancy in decision making. The more positive and committed toward vaccination, the more likely the health care provider is to promote the vaccine with his pregnant patients. The stepped up professional education campaigns and media campaigns geared to educating health care providers and pregnant women about the benefit–risk ratio of influenza vaccine during pregnancy during the H1N1 pandemic may have been effective in assisting pregnant women in making informed and potentially life-saving decisions. Similar to other pandemic research, our survey found that witnessing the pandemic had a definite impact on seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccine coverage. Lynch et al27 describe the impact of appraised threat to a pregnant women's perceptions of their vulnerability to, and the severity of, H1N1 and their subsequent preventive behavior. In our study, women in the post-pandemic group stated they were more likely to get the seasonal vaccine after witnessing the pandemic, citing both their own safety and safety of their family as reasons. In fact, our survey showed that women who believed the pandemic to be severe and who were worried about the H1N1 virus were more likely to change their opinion about seasonal influenza vaccine and immunization in general. However, we should not be quick to dismiss perceived lack of benefit of influenza vaccination as a factor contributing to suboptimal uptake. If the perceived threat is low, women will unlikely take action against it. In our survey, both cohorts reported not needing the vaccine as a reason for not getting it, similar to other reports, in which a frequently cited reason by pregnant women for declining immunization was the belief that the threat was not real, and that the vaccine was unnecessary.19,28

The study had potential limitations. Ours was a relatively small sample of mostly young, white, well-educated women, which is likely not representative of the general population of pregnant women. The inclusion criteria for the post-partum cohort were expanded to include higher risk pregnancies, which may have contributed to a slight response bias. Ongoing research in a larger population is needed, with a particular focus on predictors of maternal vaccination both during a typical vaccine season as well as during a future possible influenza pandemic.

Methods

Participants, recruitment, and ethical considerations

This study was conducted in the obstetrics outpatient clinics of the IWK Health Cente (IWK), the perinatal care center for the Halifax Regional Municipality in Nova Scotia (population 380,000). Eligible participants included all pregnant women of any trimester who were seen for prenatal care in the obstetrics clinics at the IWK or in local participating physician's offices. Recruitment in the study was passive; surveys were available to all women presenting for care in these areas. The first phase, performed from April 2005 to April 2006, included only women with low-risk pregnancies. The second phase, conducted from January to April 2011, included women with both high- and low-risk pregnancies.

The study package offered to patients included a patient information sheet, a self-directed questionnaire, and 2 self-addressed envelopes to return the questionnaire at a later date if desired. Completion of the questionnaire was taken as consent to participate. The Research Ethics Board of the IWK approved the study. No monetary compensation was offered for participating in the study. Participants were given the chance to enter a draw for a gift certificate to a baby store.

Survey

The 63-item post-pandemic survey was a modified version of the 44-item 2005–2006 pre-pandemic survey. Prior to distribution, both questionnaires were validated, tested for test-retest reliability, and pilot tested. The items encompassed demographic information, including previous vaccination behavior, as well as questions designed to elicit KABB regarding influenza vaccination (seasonal and/or pandemic H1N1) during pregnancy and in childhood. Additional questions in the post-pandemic survey were intended to elicit more information on risk factors associated with pregnancy as well as KABB regarding the H1N1 influenza pandemic and the pandemic vaccine.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were done using SAS® V8, SAS® V9, or SAS® V9.1 (PC) software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). In general, continuous variables are presented by summary statistics (i.e., mean and standard error) and categorical variables by frequency distributions (i.e., frequency counts, percentages, and their 2-sided 95% exact binomial confidence intervals). Descriptive statistics were used to estimate the proportion of respondents who answered correctly the knowledge-based questions and who had specific attitudes toward and beliefs about influenza vaccination (seasonal and/ or pandemic H1N1) in pregnancy. Overall knowledge scores were compared using t-tests. Associations between individual knowledge responses and categorical variables (age, education, ethnicity, attendance at prenatal classes, co-morbidities, health care workers vs. non-health care workers, whether or not vaccination was discussed with physician, and previous influenza vaccination) were estimated using Fisher's exact tests. Demographic and population characteristic variables were used to develop predictive models for knowledge and attitude responses. Logistic regression was used to predict binary knowledge responses, in which the model is used to predict the probability of agreeing or disagreeing with the associated statement. Ordinal logistic regression was used to predict ordered attitude responses, where the model is used to assess the degree (strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, strongly agree) to which subjects have knowledge regarding particular issues about influenza vaccination in pregnancy and childhood. The particular ordinal logistic regression model fit was a cumulative logit model. For each outcome variable, whether binary or ordered, the collection of demographic and population characteristic variables were used in a backward elimination stepwise procedure to develop a multiple regression model. Those predictor variables remaining at the termination of the stepwise procedure are summarized, and P-values are indicated. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Conclusion

Historically, societal pressures about vaccination in pregnant women have had a direct impact on vaccine coverage, which has been reflected in rates ranging from less than 10% to 33%.29 The increase in influenza vaccination rates among pregnant women in the context of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic reflects our findings that this experience appeared to change attitudes and behaviors of health care providers and their pregnant patients, consistent with what one would expect during a disease scare. This would appear to be the result of media coverage contributing to fear of the pandemic as well as enhanced public vaccination campaigns. Although this increase in coverage was sustained throughout the 2011–12 season, it is again on the declines, reflecting a potential return to habitual behaviors in the absence of the disease stimulus. We need to heed lessons learned from this pandemic and maintain the momentum with imaginative, effective, evaluable public and professional education campaigns that continue to link perceived risk of disease with the pandemic experience. If the vaccine coverage seen during the pandemic is to be maintained, public health campaigns must transform their platform to highlight the construct of ongoing personal risk to pregnant women in the face of seasonal and/or pandemic influenza.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge the statistical assistance provided by Li Li of the Canadian Center for Vaccinology.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

SM and SH receive funding from vaccine manufacturers to conduct clinical trials of influenza and other vaccines; they also receive consulting/speakers' honoraria when serving on ad hoc scientific advisory boards or giving presentations supported financially by vaccine manufacturers. All other co-authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. CDC Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59 (8):1-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McNeil S, Halperin B, MacDonald N. Influenza in pregnancy: the case for prevention. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009; 634:161-83; PMID:19280858; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-0-387-79838-7_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McNeil SA, Dodds LA, Fell DB, Allen VM,Halperin BA, Steinhoff MC, MacDonald NE. Effect of respiratory hospitalization during pregnancy on infant outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 204(6 Suppl 1):S54-7; PMID:21640231; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Advisory Committee on Immunization Statement on influenza vaccination for 2013-2014. Can Commun Dis Rep 2013; 39(ACS-4):1-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schanzer D, Langley JM, Tam TWS. Influenza attributed hospitalization rates among pregnant women, Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2007; 29:622-9; PMID:17714614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tamma PD, Ault KA, del Rio C, Steinhoff MC, Halsey NA, Omer SB. Safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 201(6):547-52; PMID:19850275; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. MacDonald NE, Riley LE. Steinhoff MC. Influenza immunization in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 114(2 Pt1):365-8; PMID:19622998; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181af6ce8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mak TK, Mangtani P, Leese J, Watson JM, Pfeifer D. Influenza vaccination in pregnancy: current evidence and selected national policies. Lancet Infect Dis 2008; 8:44-52; PMID:18156088; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization . Vaccines against influenza: WHO position paper –November 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2012; 87:461-76; PMID:23210147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, Williams JL, Swerdlow DL, Biggerstaff MS, Lindstrom S, Louie JK, Christ CM, Bohm SR, et al. . H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet 2009; 374:451-8; PMID:19643469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lapinsky SE. H1N1 novel influenza A in pregnant and immunocompromised patients. Crit Care Med 2010; 38(4 Suppl):e52-7; PMID:19935415; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c85d5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Campbell A, Rodin R, Kropp R, Mao Y, Hong Z, Vachon J, Spika J, Pelletier L. Risk of severe outcomes among patients admitted to hospital with pandemic (H1N1) influenza. CMAJ 2010; 182(4): 349-55; PMID:20159893; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1503/cmaj.091823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Advisory Committee on Immunization Statement on seasonal trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV) for 2010-2011. Can Commun Dis Rep 2010; 36(ACS-6):1-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Callaghan W, Chu S, Jamieson D. Deaths from seasonal influenza among pregnant women in the United States, 1998-2005. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 115:919-23; PMID:20410763; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d99d85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fisher BM, Scott J, Hart J, Winn V, Gibbs R, Lynch AM. Behaviours and perceptions regarding seasonal and H1N1 influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 204(6 Suppl 107):S107-11; PMID:21419386; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dodds L, McNeil SA, Fwell D, Allen VM, Coombs A, Scott J, MacDonald N. Impact of influenza exposure on rates of hospital admissions and physician visits because of respiratory illnesses among pregnant women. CMAJ 2007; 176(4):463-8; PMID:17296958; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1503/cmaj.061435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. CDC . Seasonal influenza and 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women – 10 states, 2009-10 influenza season. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010; 59:1541-5; PMID:21124293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. CDC . Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women – United States; 2010-11 influenza season. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60(32):1078-82; PMID:21849964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Henninger M, Crane B, Naleway A. Trends in influenza vaccine coverage in pregnant women, 2008 to 2012. Perm J 2013; 17(2):31-6; PMID:23704840; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7812/TPP/12-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gorman JR, Brewer NT, Wang JB, Chambers CD. Theory-based predictors of influenza vaccination among pregnant women. Vaccine 2012; 31:213-8; PMID:23123019; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Public Health Agency of Canada. Flu-Watch Reports 2012-2013 season; http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/fluwatch/12-13/index-eng.php. Accessed August 11, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Strang R, English P. Nova Scotia's response to H1N1: Summary report. Department of Health and Wellness. December 2010; http://www.novascotia.ca/DHW/publications/H1N1-Summary-Report.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ding H, Santibanez TA, Jamieson DJ, Weinbaum CM, Euler GL, Grohskopf LA, Lu PJ, Singleton JA. Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women – National 2009 H1N1 flu survey (NHFS). Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 204(6) (Suppl) S96-S106; PMID:21640233; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gilmour H, Hofmann N. H1N1 vaccination. Health Rep 2010; 21(4):63-9; PMID:21269013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eppes C, Wu A, You W, Cameron KA, Garcia P, Grobman W. Barriers to influenza vaccination among pregnant women. Vaccine 2013; 31:2874-8; PMID:23623863; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schindler M, Blanchard-Rohner G, Meier S, Martinez de Tejada B, Siegrist CA, Burton-Jeangros C. Vaccination against seasonal flu in Switzerland: The indecision of pregnant women encouraged by healthcare professionals. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2012; 60:447-53; PMID:23141298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lynch MM, Mitchell EW, Williams JL, Brumbaugh K, Jones-Bell M, Pinkney DE, Layton CM, Mersereau PW, Kendrick JS, Medina PE, et al. . Pregnant and recently pregnant women's perceptions about Influenza A Pandemic (H1N1) 2009: Implications for public health and provider communication. Matern Child Health J 2012; 16:1657-64; PMID:21822963; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10995-011-0865-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meharry PM, Colson ER, Grizas AP, Stiller R, Vazquez M. Reasons why women accept or reject the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV) during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J 2013; 17:156-64; PMID:22367067; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10995-012-0957-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Naleway AL, Smith WJ, Mullooly JP. Delivering influenza vaccine to pregnant women. Epidemiol Rev 2006; 28:47-53; PMID:16731574; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/epirev/mxj002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]