Abstract

Adolescent immunization rates for human papillomavirus (HPV) are low and interventions within school-based health centers (SBHCs) may increase HPV uptake and series completion. We examined the effect of a parent health message intervention on HPV vaccination intent, first dose uptake and series completion among adolescents who received care at SBHCs. Via computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI), 445 parents of young adolescents were randomly assigned to 2 two-level interventions using a 2 × 2 design (rhetorical question (RQ) or no-RQ and one-sided or two-sided message). The RQ intervention involved asking the parent a question they were likely to endorse (e.g., “Do you want to protect your daughter from cervical cancer?”) with the expectation that they would then behave in a manner consistent with their endorsement (i.e., agree to vaccinate). For the one-sided message, parents were given information that emphasized the safety and effectiveness of HPV vaccine, whereas the two-sided message acknowledged that some parents might have concerns about the vaccine, followed by reassurance regarding the safety and effectiveness. At CATI conclusion, parents indicated intentions to have their adolescents vaccinated. Parents who endorsed any intent were sent a consent form to return and all adolescents with signed returned consents were vaccinated at SBHCs. Medical records were reviewed for uptake/completion. Parents were 87% female; adolescents were 66% male and racially/ethnically diverse. 42.5% of parents indicated some intention to immunize, 51.4% were unsure, and 6.1% were not interested. 34% (n = 151) of adolescents received their first dose with series completion rates of 67% (n = 101). The RQ component of the intervention increased intention to vaccinate (RR = 1.45; 95%CI 1.16,1.81), but not first dose uptake or series completion. The 1-sided and 2-sided messages had no effect. This brief, RQ health intervention enhanced intent, but did not impact vaccination rates, likely due to the time delay between the intervention and consent form receipt.

Keywords: brief health messages, HPV vaccination, immunization, intervention, SBHC

Abbreviations

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- HPV4

quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine

- SBHC

School-based health center

- CATI

computer-assisted telephone interviews

- RQ

rhetorical question

- UTMB

University of Texas Medical Branch

- THC

Teen Health Center

Immunizing adolescents for human papillomavirus (HPV) in the United States (US) continues to be a struggle despite routine recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunizations Practices. US national data suggest that only about half of females and less than one quarter of males have received at least one dose of vaccine.1,2 Moreover, among those who received one dose of vaccine, series completion is lower than desired, i.e., 67% for females and 45% for males.2

Interventions that have attempted to increase HPV immunization have had mixed results and many have necessarily used vaccine intent, rather than vaccine receipt, as the primary outcome.3 In addition, most interventions have targeted vaccination intent for girls and young women using a variety of samples, including adolescents, college-enrolled women and parents of the college aged women.3 Across all groups, low rates of HPV vaccine initiation and series completion have been widely reported in the context of traditional settings, such as physician offices, where logistical and financial barriers may present obstacles to immunization.4

School-based health centers (SBHCs) in the US represent an alternative to primary care settings for immunization because most children aged ≤14 years are in school5 and SBHCs minimize common obstacles (e.g., parents missing work).6,7 Thus, it is not surprising that most US parents support SBHC immunization programs8,9 and that these programs have been shown to increase immunization rates among socially disadvantaged youth.9-12 SBHC's procedures for administering immunizations vary according to state, health center, and immunization type, i.e, required versus mandated. Generally, immunization is included as one of several health services that are afforded to children whose parents provide general SBHC consent. Despite this blanket consent, however, many SBHCs do not routinely vaccinate youth without obtaining additional permission specific to vaccination. Some call parents by phone to obtain this permission, immediately prior to vaccination while others collect a separate consent form specific to vaccination at the same time they obtain written blanket consent for general SBHC services. In addition, US SBHCs that participate in the Vaccines for Children's (VFC) program must provide a vaccine information sheet (VIS) that describes the vaccine in detail to each parent after administration. As a result, interventions promoting HPV vaccination at US SBHCs may have to be directed toward parents or guardians.

Brief health messages that may be helpful for increasing HPV vaccination rates include the use of rhetorical questions (RQ), also known as “foot-in-the-door” techniques.13 This approach involves first asking a general question that the subject is likely to endorse, followed by a more targeted question or request. The belief is that if a person agrees with the general question, s/he is more likely to agree with the targeted request, in order to be consistent. For example, Cox et al found that an RQ intervention increased intention of parents to vaccinate their daughters with HPV vaccine.14

Another approach that can be used to influence health behaviors are one-sided or two-sided messages.15 A one-sided message presents only the arguments supporting the advocated behavior. A two-sided message lists supporting arguments, but also acknowledges (and usually rebuts) one or more potential arguments against the advocated behavior. Research suggests that two-sided messages are sometimes more persuasive than one-sided messages.16

This purpose of this study was to examine the effect of brief health messaging on: parents’ intentions to vaccinate their young adolescent, the first dose uptake of HPV vaccine, and series completion. For the reasons articulated above, we decided to test these messages in SBHCs. We randomized parents to 2 sets of health messages in a 2 (RQ; no-RQ) X 2 (one-sided; two-sided) design. In addition, we targeted those parents who had already provided consent for their teen to receive care in one of these SBHCs. We believed that the provision of health messages to this group of parents, whose teens were unvaccinated, followed by elicitation of intent to vaccinate, would lead to increased vaccine uptake. We hypothesized that parents who were randomized to receive both rhetorical questions and the two-sided messages would have greater intention to vaccinate and greater first dose uptake as compared to parents who received no rhetorical question and a one-sided message.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the parent participants (n = 445) across the 4 conditions. There were no significant differences (p > .05) across the 4 groups, confirming that the randomization was successful. Parents were racially/ethnically diverse, 87.4% were female, and 55.1% were married or living with a partner. The mean age of the adolescent children was 13.5 y and 66.1% were male.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Sample (n = 445)

| Total | No RQ, 1 sided message (n = 116) | RQ, 1 sided message (n = 109) | No RQ, 2 sided message (n = 106) | RQ, 2 sided message (n = 114) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Parent Age (m, sd) | 13.5 (1.3) | 41.4 (7.5) | 42.5 (7.6) | 42.0 (8.9) | 41.2 (7.4) |

| Teen's age (m, sd) | 41.8 (7.6) | 13.3 (1.3) | 13.6 (1.4) | 13.5 (1.4) | 13.7 (1.3) |

| Female parent interviewed | 87.4 (389) | 92.2 (107) | 83.5 (91) | 89.6 (95) | 84.2 (96) |

| Son to be vaccinated | 66.1 (294) | 66.4 (77) | 63.3 (69) | 72.6 (77) | 62.3 (71) |

| Interview conducted in Spanish | 15.7 (70) | 12.9 (15) | 13.8 (15) | 20.8 (22) | 15.8 (18) |

| Parental Race | |||||

| Nonhispanic White | 30.6 (136) | 29.3 (34) | 33.9 (37) | 32.1 (34) | 27.2 (31) |

| Nonhispanic Black | 27.9 (124) | 31.9 (37) | 33.9 (37) | 20.8 (22) | 24.8 (28) |

| Hispanic | 39.8 (177) | 37.1 (43) | 29.4 (32) | 46.2 (49) | 46.5 (53) |

| Nonhispanic other | 1.8 (8) | 1.7 (2) | 2.8 (3) | 0.9 (1) | 1.8 (2) |

| Parental Education | |||||

| < High school | 14.0 (62) | 10.3 (12) | 14.7 (16) | 16.3 (17) | 14.9 (17) |

| High school or GED | 23.5 (104) | 24.1 (28) | 26.6 (29) | 20.2 (21) | 22.8 (26) |

| Some or college degree | 62.5 (277) | 65.5 (76) | 58.7 (64) | 63.5 (66) | 62.3 (71) |

| Single marital status | 44.9 (200) | 42.2 (49) | 45.0 (49) | 47.2 (50) | 45.6 (45.6) |

| Insurance type | |||||

| None | 16.9 (75) | 13.8 (16) | 16.5 (18) | 16.2 (17) | 21.1 (24) |

| Private | 46.1 (205) | 49.1 (57) | 41.3 (45) | 49.5 (52) | 44.7 (51) |

| Public (Medicaid/CHIPS) | 36.9 (164) | 37.1 (43) | 42.2 (46) | 34.3 (36) | 34.2 (39) |

Among the entire sample, 42.5% (n = 189) of parents indicated that they wanted their son or daughter immunized with HPV4. Most of the remaining parents (51.4%) were unsure (n = 229), with a small proportion (6.1%; n = 27) indicating that they were never going to immunize their teen. Almost 34% of the sample (n = 151) received their first dose. Among those parents who reported an intention to vaccinate, about 57.1% (108 of 189) received their first dose of HPV4 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of participants obtaining, first, second, and third doses of HPV4.

We computed the relative risks to determine the impact of RQ and message sidedness on intention and first dose uptake assessing both main and interaction effects. We found that RQ was significantly associated with intention to vaccinate (RR = 1.45, CI 1.16, 1.81), but not of first dose uptake (RR = 1.15, CI 0.89, 1.50). Message sidedness had no significant effect on either intention or first dose uptake. The interaction of RQ with message sidedness also was not significant. Neither RQ nor message sidedness was significantly associated with return for the second dose or with series completion. Finally, no adverse events or side effects were reported by participants from the intervention. Compared with non-vaccinated adolescents, those who received the first dose of vaccine were younger (13.1 yrs vs 13.7 yrs, P < .001) and more likely to be Hispanic than non-Hispanic (P < .04). First dose uptake did not differ by parental age, marital status, education level, gender of parent interviewed, or self-reported insurance status.

Of those who received their first dose, 81.4% returned for dose 2, with 66.9% completing the 3 dose series. (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Although the RQ increased intention to vaccinate, this behavioral effect did not impact on first dose uptake. Further message sidedness and the interaction of RQ plus message sidedness did not impact any of the main outcomes. Series completion rates among those adolescents who received their first dose was higher than has been reported in national immunization data reports.1,2 This finding was not unexpected as the use of SBHC does minimize logistic barriers that are associated with return visits necessary to complete the vaccination series.

Our finding that RQ did not affect first dose uptake was disappointing, but the significant effect on vaccine intent is consistent with other HPV research.14 However, it is possible that time delays between the intervention and the mailing of the required the consent form which took between 3–7 d may have eroded the effect of the intervention. It may be that this strategy is best suited to those situations where the vaccine decision occurs immediately following the intervention. However, this speculation requires further evaluation in settings where signed parental consent can be immediately obtained and/or technology-assisted strategies can allow a parent's consent for immunization that can be instantly delivered electronically to a SBHC, so as to enhance and improve immunization rates.

Another possible explanation for our failure to find an intervention effect on vaccine receipt was that a physician did not deliver the brief health messages. Data indicate that provider recommendation is strongly associated with vaccine intent17,18 and uptake19 and had a health care provider delivered the health messages, perhaps increased first dose uptake would have resulted. Brief messages may be most effective when delivered by a trusted health care provider in a setting where vaccines can be delivered immediately after delivery, thereby diminishing the intention-behavior gap. In addition, our categorical measure of intention did not allow us to quantify the strength level of parents’ intentions, and it could be that a certain strength level of intention is needed to facilitate dose uptake. Alternatively, it is also possible that an RQ intervention may have a stronger effect by asking parents to articulate further why they would like to protect their daughter/son from cancer by increasing the dose effect of the RQ (e.g., having a sign in waiting room with a RQ and then having provider restate the RQ), and by pairing the RQ with an implementation intervention that addresses barriers to follow through with intentions. Further research is needed to explore these issues and build on the encouraging preliminary results presented here. Finally, while SBHC can reduce many barriers to care, there also may be other barriers that we could not address that may have influenced facilitation of follow through with intentions (e.g.,, parent's concern about not being “on-site” during the vaccine adminstration9).

We failed to find any effect of the message-sidedness portion of the intervention. The two-sided message was aimed at countering unsupported concerns and increasing parents’ belief that HPV vaccination would protect their teen from anal and/or cervical cancer as well as genital warts. While educational interventions are helpful to increase acceptance in adolescent and young adult samples, education interventions among parental samples of adolescents are mixed.3 Hence, our messages may not have effectively impacted intention and vaccine receipt because parents had a more significant concern that needed to be addressed. Future research is needed to assess whether message sidedness interventions targeting multiple health beliefs or tailored specifically to the meet the parents’ health belief concerns regarding HPV vaccination increase intentions and uptake.

Several limitations deserve comment. First, although we had a minimal intervention comparison group (no-RQ + 1-sided message), we did not have a true no-intervention control group. Also, we were surprised with the relatively low numbers of parents who actually chose to immunize their teen and the large number of parents who reported being unsure as to whether or not they would vaccinate their child. While many SBHCs require parental consent for children and adolescents to be afforded care in this setting, and immunization is listed as one of several services that may be offered, most SBHC have additional policies and procedures for parents to authorize and endorse specific immunizations. Our need to obtain signed parental consent prior to administration of the HPV vaccine may have resulted in an unforeseen barrier to increased uptake, despite our health messaging intervention. Further research in alternative care settings where vaccination policies and procedures vary by geographic location and clinic policy require greater scrutiny and evaluation. For example, if our SBHC system had collected signed parental permission for HPV vaccination upon registration for SBHC services at the beginning of the school year, all students whose parents who indicated that they wanted to have their son or daughter vaccinated after our intervention could have been immunized and rates of uptake would likely have been greater. Regardless, SBHCs may wish to consider more proactive immunization policy initiatives that promote both uptake and vaccine education, especially to those who have consented to have their teen receive care at a SBHC in order to improve immunization rates of the entire school population. Our results in terms of vaccine uptake may not generalize to SBHC populations in other geographic locations or those with different immunization permission policies. It may be that vaccine uptake after brief health messaging might be more effective among schools located in states with higher or lower HPV immunization rates, or in SBHCs that collect vaccine-specific parental consent upon registration, or do not require additional vaccine-specific consent at all. It is important to note that the recommendation for routine HPV vaccination for girls was issued in 2006. Licensure for boys did not occur until 2009 and a routine recommendation was not made until 2011. While we did not find differences in the intention or in first dose uptake between male and female adolescents in our sample, parents of sons had significantly less time to understand and appreciate that this was a recommended vaccine for their sons as compared to parents of females. Finally, we were unable to access immunization records of private office practitioners or the state registry to determine immunization of those parents who indicated some intention to immunize their teenage child. In Texas, the state registry data can only be accessed by clinical care staff and is not accessible for research-only purposes whereas in other geographic locations, state and regional registries are used collaboratively by both clinicians and researchers. While we were able to document that approximately one third of parents had their teen immunized, this may represent a slight underestimate because it is possible that after receiving the intervention parents sought care at their teen's primary care provider, whose records we were unable to review.

We also had to eliminate about 10% of parents (=44) who participated in this study because they did not accurately recall or report that their teen had already received this vaccine. In examining medical records, we found that these teens had received at least one dose of the vaccine prior to study enrollment. While it is possible, that some parents wanted to participate in the study and simply ignored the inclusion/exclusion criteria, it is more likely that most of these parents forgot or did not realize that their teen had already been vaccinated which is consistent with Stupiansky et al20 finding. These data support for the use of electronic and written registries to have an accurate repository of immunization records.

In conclusion, our findings support the use of RQ to facilitate parental intention to vaccinate both male and female adolescents and is consistent with other reports using this same strategy.14 Finally, the use of SBHCs as a setting for vaccine delivery appeared to foster relatively high series completion rates and suggesting that they represent an excellent venue for delivery of multi-dose vaccines, like HPV vaccine.

Materials and Methods

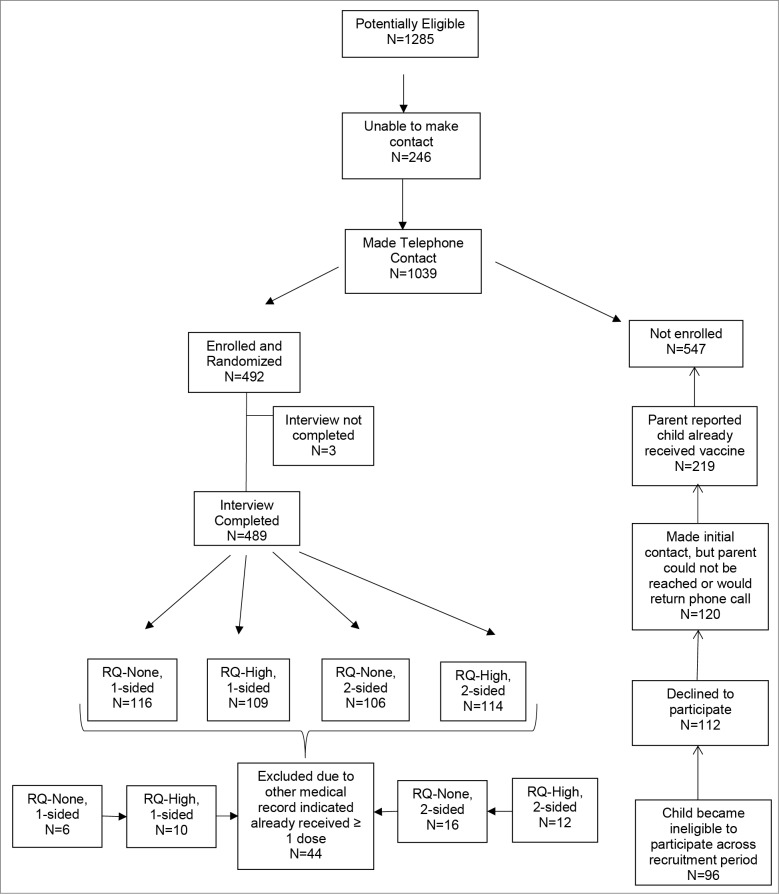

Recruitment. Participants were 445 parents of male and female adolescents (ages 11 to 15 y who had not previously received the HPV vaccine) recruited from the Teen Health Center (THC). The THC is a nonprofit organization that works in collaboration with the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), to provide health care services, including immunizations, to residents ages 0 to 21 y in Galveston County, Texas. At the time of recruitment, the THC consisted of 5 school-based health clinics (SBHCs), 3 in middle schools and 2 in high schools. All SBHCs carried and administered only the quadrivalent HPV vaccine (HPV4). Recruitment began in November of 2010 and continued until April 30, 2013 (See Fig. 1). Teen's medical records were reviewed until April 1, 2014 for series completion.

Figure 1.

Recruitment of participants.

A total of 1,285 parents were determined eligible because they had provided consent for their 11 to 15 y old to receive care at a SBHC, but we were only able to make at least one phone contact with 1,039. Of these, 492 were deemed eligible at the time of the interview, (i.e., son or daughter was between 11 and 15 y of age and had not received ≥ 1 dose of HPV vaccine) and agreed to participate, but 489 completed the entire CATI interview. Upon subsequent review of the teen's medical records, 44 of these adolescents had previously received ≥ 1 dose of HPV despite parental report of no vaccination. Therefore, data from these 44 parents and teens were excluded from all analyses.

All study procedures were approved by the IRBs at UTMB and Indiana University.

To determine eligibility, the medical records from the SBHC were reviewed (a state-wide immunization registry was not accessible to assess immunization status). Parental contact information was extracted from the THC consent form, and all potentially eligible parents were sent a letter describing the study and informing them that a member of the study team might phone them in the near future to request participation. About 1½ to 2 weeks after the mailing, a trained bilingual research assistant phoned eligible parents. If a parent was not reached by phone after 6 to 8 attempts within a 2-week period, monthly contacts for 6 months were completed. In the event that the phone line became disconnected, attempts to contact parents were continued for 2 months. Parents who were reached by phone were provided information in the language they preferred (English or Spanish) regarding the purpose of the study and its procedures. In addition, all written communication directed to the parents, including the consent form was placed on university-affiliated letterhead, i.e., UTMB and parents were not informed of the study's sponsor. This approach was approved by the UTMB institutional review board. If parents expressed interest in participating, the research assistant verified eligibility status (i.e., confirmed with parent that adolescent had not previously been vaccinated and parent had not previously participated), and obtained oral informed consent to participate in the audiotaped phone interview and parent permission to review the adolescent's medical chart for HPV vaccination status post-interview. The requirement for adolescent assent to review medical charts was waived by the IRBs.

Parents who provided consent were told the following prior to the computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI):

I will be asking questions that address your feelings and opinions about vaccines. We are interested in knowing how parents make decisions about vaccines for their children, in particular the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, so that we can develop better information for parents. Human papillomavirus has been shown to cause serious illnesses in women, like cervical cancer and to cause genital warts and other cancers in both men and women.

The research assistant then read the CATI verbatim in English or Spanish, depending on preference, and each CATI was audiorecorded. The randomization into one of 4 groups was built into the program using a random numbers table. The interview was organized as follows: pre-intervention questions including items on demographics and background information and questions regarding parental health beliefs about vaccines in general, delivery of health message intervention; and post-intervention questions covering parental health beliefs regarding the HPV vaccine and intention to vaccinate. The health message intervention was initiated first with the use of rhetorical questions (RQ) and then with the one- or two-sided message and was not blinded to the research assistant. The intervention group assignment was preprogrammed into the CATI with participants being randomized into one of 4 conditions: 1) rhetorical questions (RQ) plus one-sided message, 2) RQ plus two-sided message, 3) no RQ plus one-sided message, and 4) no RQ plus two-sided message. During the interview, the research assistant recorded all parental responses directly into a secure database. The audiorecorded CATIs were uploaded to a secure drive and reviewed to ensure fidelity to the CATI script. Each parent who completed the CATI was provided with a $40.00 gift card as compensation.

With the exception of parents who expressed no interest in having their teen vaccinated, all parents were mailed a vaccine information sheet (VIS) about the HPV4 vaccine and a consent form to sign if they wanted to have their son/daughter vaccinated at the SBHC per VFC requirements. A stamped self-addressed return envelope was included to faciliate return of the consent. In addition, those parents expressing interest in having their teen receive the vaccine at the SBHC but who did not return the form were called 2 weeks later by the research assistant and sent another VIS sheet and consent form. All teens whose parents returned a signed consent form were scheduled for appointments at the appropriate SBHC to receive the first HPV4 dose. Reminder notices for 2nd and 3rd doses, which included health messages consistent with their intervention condition, were mailed to parents 2 weeks prior to the date of the follow-up appointment. Medical records at both SBHCs and university-based clinics at UTMB subsequently were reviewed to ensure actual dose administration and completion.

Intervention

RQ Condition: Parents of adolescent girls randomized to RQ conditions were asked the following 2 yes/no questions: 1) “Do you want to protect your daughter from cervical cancer?;” and 2) “If there was a vaccine that could prevent cervical cancer, would you have your daughter get it?” For parents of adolescent boys, the RQ wording was altered to be gender appropriate by substituting genital warts for cervical cancer.

Message Sidedness Condition. Parents of adolescent girls in the 1-sided message condition were told “The HPV vaccine which you may know as Gardasil is an effective way to protect your daughter from most types of cervical cancer, genital warts, and anal cancer. This vaccine has been licensed for 5 y and over 72 million doses worldwide have been given to adolescent girls and boys as well as young adult women and men. It has been found to be very safe.” For parents of adolescent boys the 1-sided message was slightly altered, and excluded the reference to cervical cancer prevention. Parents of adolescents in the two-sided message condition received this additional statement, which has been identified as a common concern about HPV vaccination21: “Some parents want to wait until more adolescent boys/girls have been given this vaccine before getting their own son/daughter vaccinated. However, this vaccine has been licensed for 5 y and over 72 million doses worldwide have been given to adolescent girls and boys as well as young adult women and men. It has been found to be very safe.”

Measure

Prior to the administration of the intervention, parents were asked about demographic characteristics, such as date of birth, gender, country of origin, race/ethnicity, and language spoken at home. At the conclusion of the interview, after the interventions were administered, all parents were asked about their intention to get their adolesents immunized in the next month at the SBHC. Response options included: Yes; No, I don't intend to get my child vaccinated at all; Unsure; No, but I will eventually get my child vaccinated; or No, but I will eventually get my child vaccinated at UTMB.

Analytic Plan. Outcome variables included intention to vaccinate, first dose acceptance, return for second dose, and series completion. We categorized parents as intending to vaccinate if they indicated that they planned to have their teens vaccinated at the SBHC (n = 166) or a University clinic (n = 23). Those who were unsure (n = 186), indicated that they would eventually vaccinate their teen, but did not specify the location (n = 43), or stated that they were unwilling to vaccinate at all (n = 27) were all defined as non-intenders. Uptake and number of doses received were determined based on reviews of medical records at SBHCs or the university clinic.

Descriptive statistics were used to examine demographic features of the sample. To confirm successful randomization, we computed a series of chi-square analyses to confirm that no demographic characteristics differed among the 4 groups. Subsequently, relative risk analyses determined the effects of the interventions on the outcomes, i.e, intention to vaccinate, first dose uptake, and series completion. The use of relative risk estimation was chosen over odds ratios as this statistic is more directly interpretable.22 We also included an interaction term (i.e., of rhetorical question with message sidedness) to see if one of the intervention varied depending on the level of the other intervention.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Rickert serves on the US. Advisory Board for Human Papillomavirus for Merck & Co, Inc. as well as on the Merck & Co., Inc. Speaker's Bureau. In addition, Dr. Rickert previously served on the Adolescent Health and Wellness Advisory Boards for Pfizer, Inc. and is a member of the Speaker's Bureau. Drs. Auslander, Rosenthal, Rupp, and Cox have no current financial disclosures, but acknowledge that they each have been investigators on investigator initiated studies funded by Merck & Company, Inc. within the last 5 years. Dr. Zimet is an investigator on an investigator initiated study funded by Merck & Company, Inc. and has received an unrestricted program development grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

Funding

This study was supported Merck & Co., Inc. through a grant (IISP #37286) and a grant from Health and Human Services Administration (T71MC0008) to the first author. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the official view of Merck and Company, Inc., or the US. Department of Health and Human Services. These data were presented in part at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Vancouver, British Columbia in May 2014.

References

- 1. Schmidt MA, Gold R, Kurosky SK, Daley MF, Irving SA, Gee J, Nateway AL. Uptake, coverage and completion of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in the vaccine safety datalink, July 2006- June 2011. J Adolesc Health 2013; 53:637-641; PMID:24138765; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Curtis RC, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, Dorell C, Stokeley S. MacNeil J, Hariri S. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2012. MMWR 2013; 62:685-693; PMID:2398549623985496 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fu LY, Bonhomme LA, Cooper SC, Joseph JG, Zimet GD. Educational interventions to increase HPV vaccination acceptance: A systematic review. Vaccine 2014; 32:1901-20; PMID:24530401; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatrics 2013; 168:76-82; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. U. S. Department of Commerce United States Census Bureau. Enrollment status of the population 3 years old and over, by sex, age, race, Hispanic origin, foreign born, and foreign-born parentage: October 2012. Available at http:\\www.census.gov/hhes/school/data/cps/2012/tables.html. [Accessed May 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yusuf H, Averhoff F, Smith N, Brink E. Adolescent immunization: Rationale, recommendations and implementation strategies. Pediatr Ann 1998; 27:436-44; PMID:9677615; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3928/0090-4481-19980701-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boyer-Chuanroong L, Woodruff BA, Unti LM, Sumida YU. Immunizations from ground zero: Lessons learned in urban middle schools. J Sch Health 1997; 67:269-72; PMID:9358380; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1997.tb03447.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Short MB, Rupp R, Stanberry LR, Rosenthal SL. Parental acceptance of adolescent vaccines within school-based health centres. Herpes 2005; 12:23-7; PMID:16026641 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Middleman AB, Tung JS. School-located immunization programs: Do parental preferences predict behavior? Vaccine 2011; 29:3513-3516; PMID:21414378; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cassidy W. School-based adolescent hepatitis B immunization programs in the United States: Strategies and successes. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998; 17(7 suppl):S43-6; PMID:9688100; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00006454-199807001-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu H, Hynes K, Lim JM, Chung HI. Hepatitis B catch-up project: Analysis of 1999 data from the Chicago public schools. Asian Am Pac Isl J Health 2001; 9:205-10; PMID:11846366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilson T, Harman S. Analysis of a bi-state, multi-district, school-based hepatitis B immunization program. J School Health 2000; 70:408-12; PMID:11195951; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07228.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Freedman JL, Fraser SC. Compliance without pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique. J Pers Soc Psychol 1966; 4:196-202; PMID:5969145; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1037/h0023552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cox DS, Cox AD, Sturm L, Zimet G. Behavioral interventions to increase HPV vaccination acceptability among mothers of young girls. Health Psychol 2010;29:29-36; PMID:20063933; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1037/a0016942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crowley AE, Hoyer WD. An integrative framework for understanding two-side persuasion. J Consum Res 1994; 20:561-74; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/209370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hovland C, Lumsdaine A, Sheffield F. Experiments in mass communication. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gowda C, Schaffer SE, Dombkowski KJ, Dempsey AF. Understanding attitudes toward adolescent vaccination and the decision-making dynamic among adolescents, parents and providers. BMC Public Health 2012; 12:509; PMID:22768870; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2458-12-509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gargano LM, Herbert NL, Painter JE, Sales JM, Morfaw C, Rask K, Murray D, DiClemente RJ, Hughes JM. Impact of physician recommendation and parental immunization attitudes on receipt or intention to receive adolescent vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013; 9:2627-33; PMID:23883781; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/hv.25823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hofstetter AM, Rosenthal SL. Factors influencing HPV vaccination: lessons for health care professionals. Expert Rev Vaccines 2014; 13:1013-1026; PMID:24965128; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1586/14760584.2014.933076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stupiansky NW, Zimet GD, Cummings T, Fortenberry JD, Shew M. Accuracy of self-reported human papillomavirus vaccine receipt among adolescent girls and their mothers. J Adolesc Health 2012; 50:103-105; PMID:22188843; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zimet GD, Rosberger Z, Fisher WA, Perez S, Stupiansky NW. Beliefs, behaviors, and HPV vaccine: Correcting the myths and the misinformation. Prev Med 2013; 57:414.418; PMID:23732252; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greenland S. Model-based estimation of relative risks and other epidemiologic measures in studies of common outcomes and in case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol 2004. 15; 160:301-5; PMID:15286014; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/aje/kwh221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]