Abstract

In Catalonia, pertussis outbreaks must be reported to the Department of Health. This study analyzed pertussis outbreaks between 1997 and 2010 in general and according to the characteristics of the index cases. The outbreak rate, hospitalization rate and incidence of associated cases and their 95%CI were calculated. Index cases were classified in two groups according to age (<15 years and ≥15 years) and the vaccine type received: whole cell vaccine (DTwP) or acellular vaccine (DTaP). During the study period, 230 outbreaks were reported. The outbreak rate was 2.43 × 10−6 persons-year, and outbreaks ranged from 2 to 32 cases, with a median duration of 18 days. There were 771 associated cases, with an incidence rate of 0.8 × 10−5 persons-year.

After classifying outbreaks according to the age of the index case, 126 outbreaks (1.3 × 10−6 persons-year) had an index case aged <15 y and 87 (0.87 × 10−6 person-year) had an index case aged ≥15 y (RR = 1.44, 95%CI 1.10–1.90; P = 0.007).

Between 2003 and 2010, after the introduction of the acellular vaccine, the index case was vaccinated with DTwP vaccine in 25 outbreaks (0.43 × 10−6 persons-year) and with DTaP vaccine in 32 outbreaks (0.55 × 10−6 person-year) (RR = 0.78, 95%CI 0.46–1.31; P = 0.35).

Of cases, 37.2% were correctly vaccinated, suggesting waning immunity of pertussis vaccine protection and endogenous circulation of pertussis. A greater number of outbreaks had an index case aged <15 y. No changes in the disease incidence, associated cases and hospitalization rate were observed after the introduction of DTaP.

Keywords: pertussis, hospitalization, surveillance, whole cell pertussis vaccine, acellular pertussis vaccine

Introduction

Pertussis is an infectious disease caused by B. pertussis. Typical pertussis disease in infants lasts 2 to 6 wk and consists of three stages: catarrhal (1–2 wk), paroxysmal (1–6 wk) and convalescence (1–2 wk).1 The clinical characteristics of pertussis differ between infants, young people and adults. Infants have cough ≥2 wk and at least one of the following symptoms: paroxysmal cough, inspiratory whoop, posttussive vomiting or apnea. Young people and adults have mild symptoms, usually only long, persistent cough.2 The epidemiology of pertussis shows a cyclic pattern, with epidemic peaks every 3–5 y.3-7

Pertussis is highly transmissible in the catarrhal stage, resulting in frequent outbreaks that are difficult to detect and control.8 Outbreaks typically occur in schools (high, middle or elementary) or other institutions when vaccine protection against pertussis begins to wane.8

Poland et al.9 reported varying reasons for increases in pertussis outbreaks in the USA, including waning immunity, new B. pertussis circulating strains, various (and confusing) recommendations for DTaP vaccination and high transmissibility. In Europe, as in North America, the reasons for the increasing incidence of pertussis are not clear, but may include the change from DTwP to DTaP, the introduction of better diagnostic analyses, and changes in B. pertussis populations.10

The aim of this study was to analyze pertussis outbreaks from 1997 to 2010 in Catalonia according to the characteristics of the index case.

Results

Between 1997 and 2010, 230 outbreaks were reported. The outbreak rate was 2.43 × 10−6 persons-year (p-y). The median outbreak size was 2 (range 2–32), the median outbreak duration was 18 d (range 0–150) and the median hospitalization duration was 8 d (range 1–59). There were 771 cases and the incidence rate was 0.8 x10−5p-y. Of the 771 cases, 287 (37.2%) were correctly vaccinated, 20 (2.6%) were poorly vaccinated, 152 (19.7%) had an unknown vaccination status and 312 (40.5%) were unvaccinated. Of unvaccinated cases, 149 were born before 1981 and 94 cases were non-preventable due to an age <2 mo.

A total of 147 cases were hospitalized (rate: 1.55 × 10−5 p-y), of which 43 (29.2%) were correctly vaccinated, 4 (2.7%) were poorly vaccinated, 8 (5.4%) had an unknown vaccination status and 92 were unvaccinated (1 born before 1981 and 91 non-preventable).

The primary attack rate was 57.57% (± 22.32%) and the secondary attack rate was 35.55% (± 18.96%).

The incidence rates in males and females by age group are shown in Table 1. There was one death during the study period (in 2004); the mortality rate was 0.01 × 10−5 p-y.

Table 1. Associated cases rate by age group and sex. Catalonia, 1997–2010.

| Affected | Incidence rate* (95%CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | Total | Male | Female | RR | P |

| <1 y | 19.08 (16.42–22.05) | 19.63 (15.93–23.92) | 18.49 (14.79–22.84) | 0.94 (0.70–1.27) | 0.743 |

| 1–4 y | 2.58 (2.09–3.15) | 1.91 (1.35–2.64) | 3.29 (2.51–4.24) | 1.72 (1.12–2.67) | 0.011 |

| 5–9 y | 1.91 (1.53–2.37) | 1.86 (1.34–2.52) | 1.97 (1.42–2.66) | 1.06 (0.67–1.66) | 0.881 |

| 10–14 y | 1.45 (1.11–1.85) | 1.32 (0.89–1.88) | 1.58 (1.10–2.21) | 1.20 (0.71–2.03) | 0.545 |

| 15–24 y | 0.26 (0.17–0.37) | 0.15 (0.07–0.29) | 0.37 (0.23–0.57) | 2.46 (1.08–6.10) | 0.030 |

| 25–44 y | 0.47 (0.40–0.55) | 0.31 (0.23–0.41) | 0.65 (0.52–0.79) | 2.08 (1.47–2.99) | < 0.001 |

| >45 y | 0.11 (0.08–0.15) | 0.08 (0.05–0.14) | 0.13 (0.09–0.19) | 1.55 (0.79–3.13) | 0.226 |

Per 100 000 person-year; CI, confident interval; RR, Rate Ratio.

The setting of the outbreak was the family in 211 outbreaks (91.7%), the school in 16 (7.1%) and other (holiday camp or mountain refugee) in 3 (1.2%).

A total of 204 (88.7%) outbreaks were microbiologically confirmed, 20 (8.7%) were not confirmed microbiologically, 2 (0.9%) outbreaks were suspected and in 4 (1.7%).

In microbiologically-confirmed outbreaks, the laboratory test used to diagnose cases was PCR in 159 (69.7%) outbreaks, combined PCR and culture in 44 (19.3%), culture in 14 (6.1%), and serology in 7 (3.1%) outbreaks. In 4 outbreaks, no information was available.

One-hundred-and-sixty-six outbreaks occurred during the warm season, and 64 during the cold season (P < 0.001).

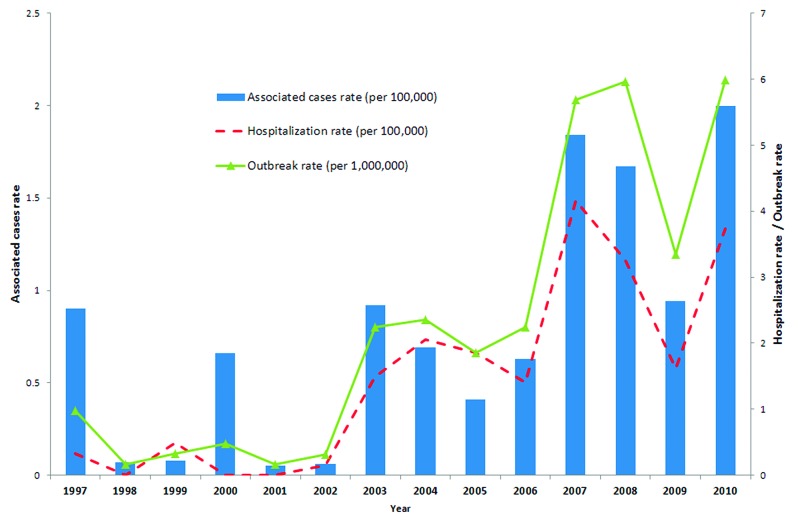

Figure 1 shows the annual rate of cases, hospitalizations and outbreaks.

Figure 1. Pertussis outbreaks, associated cases and hospitalization rates by year. Catalonia, 1997–2010.

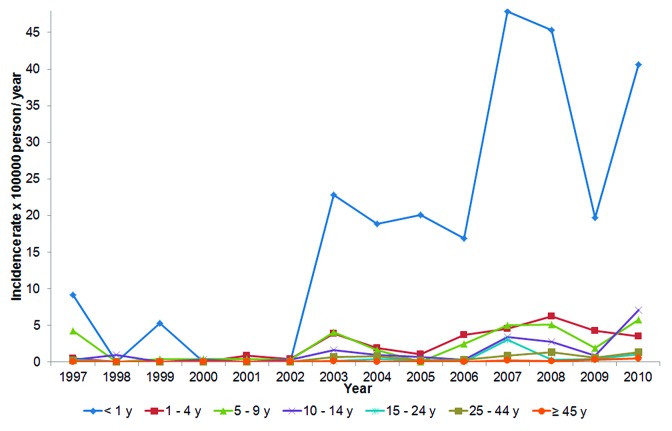

Figure 2 shows cases according to age group (<1 y, 1–4 y, 5–9 y, 10–14 y, 15–24 y, 25–44 y and ≥45 y).

Figure 2. Pertussis cases associated with reported outbreaks by age group and year. Catalonia, 1997–2010.

Classification of outbreaks according to the age of the index case showed that 126 outbreaks (1.3 × 10−6 p-y) had an index case aged <15 y and 87 (0.87 × 10−6 p-y) had an index case aged ≥15 y (RR = 1.44, 95%CI; 1.10–1.90; P = 0.007). The size of the outbreak was 413 cases (0.4 × 10−5 p-y) in outbreaks with an index case aged >15 y and 256 cases (0.3 × 10−5 p-y) in outbreaks with an index case aged ≥15 y (RR = 1.61, 95%CI 1.38–1.85; P < 0.001). The hospitalization rate was 0.6 × 10−5 p-y and 0.1 × 10−5p-y in outbreaks with an index case aged <15 y and ≥15 y, respectively (RR = 8.28, 95%CI 3.78–18.15; P < 0.001). The outbreak duration was 13 d (range 0–103) and 24 d (range 4–150) in outbreaks in which the index case was aged <15 y and ≥15 y, respectively (P < 0.001).

The index case was vaccinated with DTwP in 25 outbreaks (0.43 × 10−6 p-y) and DTaP vaccine in 32 outbreaks (0.55 × 10−6 p-y) (RR = 0.78, 95%CI 0.46–1.31; P = 0.35). There were 75 associated cases in outbreaks with index cases vaccinated with DTwP (0.13 × 10−5 p-y) and 92 (0.16 × 10−5 p-y) in outbreaks with index cases vaccinated with DTaP (RR = 0.16; 95%CI 0.60–1.10; P = 0.18). There were 17 hospitalized cases (0.029 × 10−5 p-y) in outbreaks with index cases vaccinated with DTwP and 16 cases (0.027 × 10−5 p-y) in outbreaks with index cases vaccinated with DTaP (RR = 1.06, 95%CI 0.53–2.10; P = 0.86).

Discussion

The results of this study show that pertussis outbreaks have increased significantly in Catalonia between 1997 and 2010, especially from 2003 onwards. Increases were also observed in the incidence of outbreak-associated cases and outbreak-associated hospitalization rates. The incidence of pertussis increased between the beginning and the end of the study period in all age groups, with the biggest increase being in the <1 y age group. These results are in agreement with other studies performed in the last decade.11-17

Changes in the pertussis vaccination schedule in Catalonia occurred during the study period, similar to those occurring in other countries, such as Sweden, Italy and Finland.18-21 These changes and changes introduced in the pertussis surveillance system in Catalonia make it difficult to interpret the data.

Our results show a high percentage of cases correctly vaccinated. This may be explained by waning immunity, as suggested by other reports.22-24

From 2003 onwards, the age distribution of affected cases show highest incidence in infants aged <1 y. Before 2003, the incidence according to age groups showed a different pattern. In New South Wales (Australia), the age pattern found was similar to ours, with the highest incidence being found in the <1 y age group between 2004 and 2009.25

The rate of outbreaks was higher in the warm season (April to September) in our study. Likewise, in a study performed in the US, the incidence of pertussis and hospitalizations was higher in the summer months of July, August and September.26 However, a Canadian study found a greater number of pertussis outbreaks during the winter (November to March).23

Our results show differences according to sex in some age groups. The 25–44 y age group included a higher percentage of women who had recently been mothers or who had continuous contact with infants. This suggests a need to vaccinate this specific group of subjects and was the rationale to include the vaccination of pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy (weeks 27–36) in Catalonia in early 2014.27

Outbreaks with an index case aged <15 y had a higher outbreak rate, a higher incidence of associated cases and a higher hospitalization rate than outbreaks with an index case aged ≥ 15 y, although the duration of outbreaks was shorter. This may be due to surveillance: it seems that more rapid and effective surveillance is related to outbreaks where the index cases are aged <15 y, resulting in a higher number of cases and hospitalizations. In contrast, outbreaks in which the index cases were aged ≤15 y had a longer duration due to the mild clinical symptoms, which make it more difficult to discover the outbreak and result in fewer cases testing positive.

Difficulties in performing laboratory tests may have affected the study results.28 In Catalonia, serology tests which, according to the Centers for Disease Control of the USA, are the best tests to carry out in cases with cough of between 2 and 8 wk, are not included in the routine analysis of pertussis.29 These cases represent adults and adolescents in whom the only symptom is a cough of long duration. As a result, outbreaks with an index case aged ≥15years are more difficult to detect and secondary cases harder to identify. The importance of the test was shown by Elomaa et al21 in Finland, where serology was performed in 82% of suspected cases of pertussis of all ages; however, in infants aged <2 y, 86% of cases were tested using PCR/culture.

After the introduction of a new vaccine, some changes in the incidence of pertussis were expected. In Australia, the change from DTwP to DTaP occurred between 1999 and 2000. Although one study shows differences in hospitalizations after the introduction of DTaP, this change was not followed by differences in pertussis notifications.18

In Sweden, a study performed after the introduction of DTaP in 1996 found a decrease in pertussis incidence in children under school age and a reduction in the hospitalization rate.19 The study ended in 2000, three years after the introduction of DTaP and the results were, at first, inspiring. However, Sweden was in an unusual situation with respect to pertussis vaccination: DTwP was withdrawn in 1979 and there had been no pertussis vaccination until the inclusion of DTaP in 1996.30 In Catalonia, whole vaccines were not withdrawn, but were replaced by acellular vaccines in 2002. Between 2003 and 2010, outbreaks occurred in Catalonia in which the index cases were vaccinated with one type of vaccine and others whose index cases were vaccinated with the other type of vaccine. After analyzing whether DTaP affected the behavior of pertussis outbreaks, our results show a higher outbreak rate and a higher incidence of associated cases in outbreaks where index cases were vaccinated with DTaP, although the results were not significant.

Our study had some limitations. Some cases were unvaccinated because they were born before 1981 when the routine schedule had not been introduced. Likewise, the changes introduced in pertussis surveillance in 2003 in Catalonia may also have influenced the results observed.

The recent inclusion of pregnant women in the vaccination schedule might result in changes in the epidemiology of pertussis in Catalonia in the near future, and therefore more research will be needed.

In conclusion, our results show an increase in the rate of pertussis outbreaks, the incidence of outbreak-associated cases and the outbreak-associated hospitalization rate between 1997 and 2010. As nearly 40% of cases were correctly vaccinated, the results suggest waning immunity of pertussis vaccine protection. No reduction was observed in pertussis incidence after the introduction of DTaP. In outbreaks in which the index case is aged ≥ 15 y, rapid intervention is recommended in order to detect further cases which are in the earliest phase of the disease and thereby immediately break pertussis transmission.

Methods

Catalonia is a region in the northeast of Spain with more than 7.5 million inhabitants. Pertussis vaccine was introduced in Catalonia in 1965, but in 1981 DTwP was introduced in the routine vaccination schedule at 3, 5, and 7 mo. In 1999, the schedule changed to 2, 4 and 6 mo of age and two booster doses were included at 18 mo and 4–6 y. In 2000, DTaP appeared and, in 2002, replaced the previous vaccine. In 2012, the last booster dose of vaccine was replaced by an acellular vaccine with less antigenic charge (Tdap).27,31

Pertussis outbreaks must be reported to the epidemiology surveillance system since 1997 in Catalonia. Epidemiologists must fill in a specific report for each case or outbreak, with information about the pertussis case or index case and contact cases in outbreaks. The PCR test became available in 2003, when a pilot program introduced improvements in pertussis surveillance. Since 2005, all samples are sent to a pertussis reference laboratory.32

We made a descriptive study of pertussis outbreaks between 1997 and 2010. All outbreak reports received by the Department of Health of the Generalitat of Catalonia were reviewed. For each index case and associated case, the following variables were collected: sex, age, hospitalization, vaccination status, type of vaccine received, disease duration, outbreak duration, number of infected cases, number of exposed persons, outbreak setting, type of laboratory test and outbreak starting date. The number of secondary cases was collected in order to calculate the attack rate.

Years were divided into the warm months (April to September) and the cold months (October to March). The incidence rate of outbreaks, cases associated with outbreaks and hospitalized cases in the whole period and yearly, attack rates and the mortality rate were calculated. The rate ratios (RR) and their 95%CI were calculated globally and by sex.

The index case, defined as the first case with clinical symptoms, which was taken as the origin of the outbreak, was identified for each outbreak.

Outbreaks in which the index case was unknown were not included. Outbreaks were classified according to the age of the index case (<15 y and ≥15 y) and according to the type of vaccine received by the index case.

Medians were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Age groups were compared using the rate ratios (RR) and their 95%CI. Outbreaks were studied according to the type of vaccine received by the index case between 2003 and 2010: index cases were classified as: vaccinated with DTwP (born before 2002) or with DTaP (born in 2002 and after). Statistical significance was established as P < 0.05. Data were analyzed using the SPSS v.18 and R programs. The denominators used for the incidence rates were taken from the estimated population of Catalonia provided by Idescat (Statistical Institute of Catalonia).33

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the other members of the Pertussis Surveillance Group of Catalonia, Pedro Plans, Glòria Carmona, Yolanda Jordan, Irene Barrabeig, César Arias, Mònica Carol, Neus Camps, Miquel Alsedà, and José Álvarez, and reporting physicians and staff of the epidemiological surveillance units who participated in the notification of cases and in collecting vaccination histories.

Funding

This study was partially funded by CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), and AGAUR (expedient 2009 SGR 42).

Glossary

Abbreviations,

- DTwP

Diphtheria, tetanus, whole cell pertussis vaccine

- DTaP

Diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis vaccine

- CI

Confidence Interval

- p-y

persons-year

- RR

rate ratio

References

- 1.Feigin RD, Cherry J, Harrison N, Kaplan M. Pertussis and other Bordetella infections. In: Feigin RD, ed. Feigin and Cherry's Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2009; 1683-706. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherry JD, Tan T, Wirsing von König CH, Forsyth KD, Thisyakorn U, Greenberg D, Johnson D, Marchant C, Plotkin S.. Clinical definitions of pertussis: Summary of a Global Pertussis Initiative roundtable meeting, February 2011. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:1756 - 64; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/cid/cis302; PMID: 22431797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards K, Decker MD. Whooping cough vaccine. In Vaccines. 6th edition. Edited by Plotkin SA, Orenstein W, Offit P. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2012;447–92. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochwald O, Bamberger E, Srugo I.. The return of pertussis: who is responsible? What can be done?. Isr Med Assoc J 2006; 8:301 - 7; PMID: 16805225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gregory DS.. Pertussis: a disease affecting all ages. Am Fam Physician 2006; 74:420 - 6; PMID: 16913160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsyth KD, Wirsing von Konig CH, Tan T, Caro J, Plotkin S.. Prevention of pertussis: recommendations derived from the second Global Pertussis Initiative roundtable meeting. Vaccine 2007; 25:2634 - 42; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.017; PMID: 17280745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berti E, Chiappini E, Orlandini E, Galli L, de Martino M.. Pertussis is still common in a highly vaccinated infant population. Acta Paediatr 2014; 103:846 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/apa.12655; PMID: 24716812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weekly Epidemiological Record.. Pertussis vaccines: WHO position paper No 40. 2010; 85:385 - 400 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poland GA.. Pertussis outbreaks and pertussis vaccines: new insights, new concerns, new recommendations?. Vaccine 2012; 30:6957 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.084; PMID: 23141958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bart MJ, Harris SR, Advani A, Arakawa Y, Bottero D, Bouchez V, Cassiday PK, Chiang CS, Dalby T, Fry NK, et al.. Global population structure and evolution of Bordetella pertussis and their relationship with vaccination. MBio 2014; 5:e01074 - 14; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/mBio.01074-14; PMID: 24757216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celentano LP, Massari M, Paramatti D, Salmaso S, Tozzi AE, EUVAC-NET Group.. Resurgence of pertussis in Europe. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005; 24:761 - 5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/01.inf.0000177282.53500.77; PMID: 16148840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacombe K, Yam A, Simondon K, Pinchinat S, Simondon F.. Risk factors for acellular and whole-cell pertussis vaccine failure in Senegalese children. Vaccine 2004; 23:623 - 8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.07.007; PMID: 15542182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vickers D, Mainar-Jaime RC, Pahwa P.. Pertussis in rural populations of Saskatchewan (1995 to 2003): incidence, seasonality, and differences among cases. Can J Public Health 2006; 97:459 - 64; PMID: 17203725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stehr K, Cherry JD, Heininger U, Schmitt-Grohé S, uberall M, Laussucq S, Eckhardt T, Meyer M, Engelhardt R, Christenson P.. A comparative efficacy trial in Germany in infants who received either the Lederle/Takeda acellular pertussis component DTP (DTaP) vaccine, the Lederle whole-cell component DTP vaccine, or DT vaccine. Pediatrics 1998; 101:1 - 11; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1542/peds.101.1.1; PMID: 9417143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broutin H, Mantilla-Beniers NB, Simondon F, Aaby P, Grenfell BT, Guégan JF, Rohani P.. Epidemiological impact of vaccination on the dynamics of two childhood diseases in rural Senegal. Microbes Infect 2005; 7:593 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.12.018; PMID: 15820150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bamberger ES, Srugo I.. What is new in pertussis?. Eur J Pediatr 2008; 167:133 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00431-007-0548-2; PMID: 17668241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hellenbrand W, Beir D, Jensen E, Littmann M, Meyer C, Oppermann H, Wirsing von König CH, Reiter S.. The epidemiology of pertussis in Germany: past and present. BMC Infect Dis 2009; 25:9 - 12; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2334-9-22; PMID: 19243604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott E, McIntyre P, Ridley G, Morris A, Massie J, McEniery J, Knight G.. National study of infants hospitalized with pertussis in the acellular vaccine era. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004; 23:246 - 52; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/01.inf.0000116023.56344.46; PMID: 15014301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olin P, Gustafsson L, Barreto L, Hessel L, Mast TC, Rie AV, Bogaerts H, Storsaeter J.. Declining pertussis incidence in Sweden following the introduction of acellular pertussis vaccine. Vaccine 2003; 21:2015 - 21; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00777-6; PMID: 12706691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tafuri S, Gallone MS, Martinelli D, Prato R, Chironna M, Germinario C.. Report of a pertussis outbreak in a low coverage booster vaccination group of otherwise healthy children in Italy. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13:541 - 6; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2334-13-541; PMID: 24225304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elomaa A, He Q, Minh NNT, Mertsola J.. Pertussis before and after the introduction of acellular pertussis vaccines in Finland. Vaccine 2009; 27:5443 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.07.010; PMID: 19628060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sin MA, Zenke R, Rönckendorf R, Littmann M, Jorgensen P, Hellenbrand W.. Pertussis outbreak in primary and secondary schools in Ludwigslust, Germany demonstrating the role of waning immunity. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009; 28:242 - 4; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/INF.0b013e31818a5d69; PMID: 19209094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fathima S, Ferrato C, Lee BE, Simmonds K, Yan L, Mukhi SN, Li V, Chui L, Drews SJ.. Bordetella pertussis in sporadic and outbreak settings in Alberta, Canada, July 2004-December 2012. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:48 - 56; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2334-14-48; PMID: 24476570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sala-Farré MR, Arias-Varela C, Recasens-Recasens A, Simó-Sanahuja M, Muñoz-Almagro C, Pérez-Jové J.. Pertussis epidemic despite high levels of vaccination coverage with acellular pertussis vaccine. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2013; Forthcoming http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.eimc.2013.09.013; PMID: 24216286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spokes PJ, Quinn HE, McAnulty M.. Review of the 2008-2009 pertussis epidemic in NSW: notifications and hospitalizations. N S W Public Health Bull 2010; 21:7 - 8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1071/NB10031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Brien JA, Caro JJ.. Hospitalization for pertussis: profiles and case costs by age. BMC Infect Dis 2005; 5:57 - 65; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2334-5-57; PMID: 16008838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vilajeliu A, Urbiztondo L, Martínez M, Batalla J, Cabezas C. Vacunació de les dones embarassades contra la tos ferina a Catalunya. [Vaccination in pregnant againts pertussis women in Catalonia] In: Generalitat de Catalunya. Barcelona: Agència de Salut Pública de Catalunya, 2014. Catalan. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Druzian AF, Brustoloni YM, Oliveira SM, Matos VT, Negri AC, Pinto CS, Asato S, Urias CdosS, Paniago AM.. Pertussis in the central-west region of Brazil: one decade study. Braz J Infect Dis 2014; 18:177 - 80; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.08.006; PMID: 24275370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pertussis (Whooping cough). Diagnosis confirmation [Internet]. Atlanta: CDC 1946-[cited 2013] Availabe from: http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/clinical/diagnostic-testing/diagnosis-confirmation.html

- 30.Nilsson L, Lepp T, von Segebaden K, Hallander H, Gustafsson L.. Pertussis vaccination in infancy lowers the incidence of pertussis disease and the rate of hospitalisation after one and two doses: analyses of 10 years of pertussis surveillance. Vaccine 2012; 30:3239 - 47; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.089; PMID: 22094282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Generalitat de Catalunya. Departament de Sanitat i Seguretat Social: Manual de vacunacions. [Vaccination Manual] Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya; 2006. Catalan. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Generalitat de Catalunya... Resultats del programa pilot de vigilancia de la tosferina a Catalunya. [Results of the pilot program of pertussis surveillance in Catalonia] Barcelona [Catalan.]. Butlletí Epidemiològic de Catalunya 2005; 26:1 - 8 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institu d'Estadística de Catalunya (IDESCAT). Municipal Population Register. Idescat 2014: Available from: http://www.idescat.cat/cat/poblacio/poblestimacions.html Catalan.