Abstract

The present study compared two putative pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse and dependence, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and pregnanolone, with two Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved pharmacotherapies, naltrexone and acamprosate. Experiment 1 assessed the effects of different doses of DHEA, pregnanolone, naltrexone, and acamprosate on both ethanol- and food-maintained responding under a multiple fixed-ratio (FR)-10 FR-20 schedule, respectively. Experiment 2 assessed the effects of different mean intervals of food presentation on responding for ethanol under an FR-10 variable-interval (VI) schedule, whereas Experiment 3 assessed the effects of a single dose of each drug under a FR-10 VI-80 schedule. In Experiment 1, all four drugs dose-dependently decreased response rate for both food and ethanol, although differences in the rate-decreasing effects were apparent among the drugs. DHEA and pregnanolone decreased ethanol-maintained responding more potently than food-maintained responding, whereas the reverse was true for naltrexone. Acamprosate decreased responding for both reinforcers with equal potency. In Experiment 2, different mean intervals of food presentation significantly affected the number of food reinforcers obtained per session; however, changes in the number of food reinforcements did not significantly affect responding for ethanol. Under the FR-10 VI-80 schedule in Experiment 3, only naltrexone significantly decreased both the dose of alcohol presented and blood ethanol concentration (BEC). Acamprosate and pregnanolone had no significant effects on any of the dependent measures, whereas DHEA significantly decreased BEC, but did not significantly decrease response rate or the dose presented. In summary, DHEA and pregnanolone decreased ethanol-maintained responding more potently than food-maintained responding under a multiple FR-10 FR-20 schedule, and were more selective for decreasing ethanol self-administration than either naltrexone or acamprosate under that schedule. Experiment 2 showed that ethanol intake was relatively independent of the density of reinforcement in the food-maintained component, and Experiment 3 showed that naltrexone was the most effective drug at the doses tested when the density for food reinforcement was low and maintained under a variable-interval schedule.

Keywords: ethanol, multiple schedules, DHEA, pregnanolone, naltrexone, acamprosate, rat

Introduction

In 2010, 7% of the U.S. population age 12 or older, or an estimated 17.9 million persons, met the criteria listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders for alcohol dependence or abuse (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011). Compounding this social and economic problem is the lack of suitable pharmacotherapeutic options for treatment. Naltrexone (Depade®, ReVia®) and acamprosate (Campral®) are two FDA-approved compounds for alcohol abuse and dependence, but both have substantial limitations clinically (Ross & Peselow, 2009). For instance, the opioid antagonist naltrexone has limited efficacy except in a subset of individuals, such as those with: 1) a family history of alcohol dependence, 2) an enhanced opioid response to ingestion of alcohol, 3) enhanced alcohol cravings, or 4) a specific μ-opioid receptor polymorphism response (Oslin, Berrettini, & O’Brien, 2006; Pettinati & Rabinowitz, 2006; Ross & Peselow, 2009). Likewise, experiments involving the synthetic homotaurine derivative acamprosate suggest that it is only fully effective in highly motivated subjects with a “goal of abstinence” (Mason & Ownby, 2000), and that the combined experience of acamprosate with ethanol is necessary for decreasing ethanol intake (Hölter, Landgraf, Zieglgänsberger, & Spanagel, 1997). In addition, the mechanism by which acamprosate modulates ethanol intake is poorly understood.

Due to the well-documented limitations of currently available therapies, effective treatments for alcohol abuse and dependence remain an active area of investigation in the alcohol research field. Two promising compounds are the neurosteroids dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and pregnanolone, which have been shown to decrease voluntary home-cage ethanol intake and operant responding for ethanol reinforcement in male rats, likely via negative and positive modulation of the GABAA receptor, respectively (Amato, Hulin, & Winsauer, 2012; Gurkovskaya, Leonard, Lewis, & Winsauer, 2009; Hulin, Amato, & Winsauer, 2012). For these substances to be viable clinical options for the treatment of alcohol abuse, however, they should be at least as effective as current treatment options, and ideally, demonstrate selectivity for ethanol-maintained behavior relative to other behaviors (Haney & Spealman, 2008; Wojnicki, Rothman, Rice, & Glowa, 1999). One pre-clinical strategy for assessing the selectivity of potential treatments is to compare their effects on operant responding for more than one type of reinforcer within the same experimental session under a multiple schedule. This strategy has been effective for comparing cocaine and food reinforcement (Kleven & Woolverton, 1990; Mello, Kamien, Lukas, Drieze, & Mendelson, 1993; Woolverton & Virus, 1989), ethanol and food reinforcement (Amato et al., 2012), and ethanol and alternative liquid reinforcers (Czachowski, Samson, & Denning, 1999; Shelton & Grant, 2001; Slawecki, Hodge, & Samson, 1997). These types of studies are also valuable for studying behavioral variables that can affect drug and ethanol self-administration, such as response rate, reinforcement density, availability of non-drug reinforcers, or deprivation level. For example, increased food deprivation has been consistently shown to increase drug and ethanol self-administration (Carr, 1996; Carroll & Boe, 1984; Carroll, Stotz, Kliner, & Meisch, 1984; Kliner & Meisch, 1989; Meisch & Lemaire, 1991). Unlike food deprivation, the availability of alternative non-drug reinforcements such as sucrose or food can either increase (Shahan & Burke, 2004; Weatherly, Bishop, & Borowiak, 2004; Winsauer & Thompson, 1991) or decrease drug self-administration, particularly under schedules of reinforcement that operate concurrently (Campbell & Carroll, 2000; Carroll, Rodefer, & Rawleigh, 1995; Cosgrove & Carroll, 2003; Samson, Roehrs, & Tolliver, 1982).

In Experiment 1 of the present study, responding for both ethanol and food pellets was maintained under two separate fixed-ratio (FR) schedules with different stimuli that alternated throughout an experimental session. This “multiple” schedule (Ferster & Skinner, 1957) was used to compare the selectivity of DHEA and pregnanolone with the selectivity of naltrexone and acamprosate. Both naltrexone and acamprosate have been shown to decrease voluntary ethanol intake in rats (Boismare et al., 1984; Le Magnen et al., 1987; Stromberg, Mackler, Volpicelli, & O’Brien, 2001), but to our knowledge, no studies have compared them directly with multiple neurosteroids. Of the studies examining the effects of naltrexone and acamprosate on operant responding for ethanol in rats (Hölter et al., 1997; Hyytia & Sinclair, 1993), only a few have tested the specificity of these compounds by determining their effects on reinforcers other than ethanol (Bienkowski, Kostowski, & Koros, 1999; Heyser, Schulteis, Durbin, & Koob, 1998; Middaugh, Kelley, Cuison, & Groseclose, 1999). Moreover, the results of those studies have been mixed. For example, Samson & Doyle (1985) reported that doses up to 20 mg/kg of naloxone (an opioid antagonist similar to naltrexone) did not affect operant responding for sucrose, while Schwarz-Stevens, Files, & Samson (1992) found that doses of naloxone as low as 1 mg/kg reduced responding for sucrose. Studies investigating the selectivity of acamprosate on operant behavior are also scarce in the literature, as a majority of the animal studies have focused on the effect of acamprosate on the alcohol-deprivation effect (Heyser, Moc, & Koob, 2003; Spanagel, Hölter, Allingham, Landgraf, & Zieglgänsberger, 1996) or “drug-seeking” behavior (Czachowski, Legg, & Samson, 2001). When Czachowski & DeLory (2009) did compare the effect of acamprosate on operant responding for ethanol and sucrose, they found that acamprosate decreased both ethanol- and sucrose-maintained responding non-selectively.

Experiment 2 was designed to probe the role of food reinforcement in maintaining ethanol self-administration under a multiple schedule, whereas Experiment 3 examined the effects of all of the drugs on ethanol self-administration when the number of food reinforcements was maintained at a low level under a VI-80 schedule. As mentioned above, reinforcement rate is one of the many behavioral variables that can mediate self-administration behavior as well as mediate the effects of another drug upon schedule-controlled behavior (cf. Lucki & DeLong, 1983; MacPhail & Gollub, 1975). Given that the response and reinforcement rate have generally differed for each reinforcer in previous experiments using a multiple FR FR schedule (Amato et al., 2012; Ginsburg, Koek, Javors, & Lamb, 2005), showing that these variables were not responsible for the observed selectivity of DHEA seemed essential to supporting its potential as a pharmacotherapy for alcohol abuse and dependence. For these reasons, a variable-interval (VI) schedule of food presentation that produced comparable numbers of reinforcements between components was selected from Experiment 2, and behaviorally effective doses of all of the drugs were retested.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Twenty-five male Long-Evans hooded rats served as subjects. Sixteen of these were used for Experiment 1, whereas 9 naïve rats were purchased and trained for Experiments 2 and 3. Males were used exclusively to limit the differential influence of ovarian hormones on self-administration behavior (Anker & Carroll, 2010, 2011). Eight of the subjects serving in Experiment 1 were involved in a previous experiment during which they received subchronic administration of lorazepam (n = 3), DHEA (n = 1), or vehicle (n = 3) during adolescence (postnatal days 35–64) (Hulin et al., 2012). These adolescent treatments were found to alter their preference for ethanol or saccharin, but following behavioral training under the operant procedure detailed below, the effects of adolescent exposure were no longer evident. More specifically, responding for ethanol under the multiple schedule was fairly homogeneous for the group (i.e., comparable to other groups trained in the laboratory) and the effects of the drugs were similar across subjects within the group. The remaining 9 subjects serving in Experiment 1 had a history of responding under a multiple FR-10 FR-20 schedule of ethanol and food reinforcement, respectively, and were tested acutely with several drugs (Amato et al., 2012).

Subjects were housed in polypropylene cages with hardwood chip bedding, and the colony room was maintained at 21 ± 2 °C with 50 ± 10% relative humidity on a 14:10 light/dark cycle, respectively. Water was provided ad libitum. Subjects were maintained at 90% of their free-feeding weight by food pellets obtained during the experimental sessions (TestDiets, a division of LabDiet, Richmond, IN) and supplemental rodent chow provided several hours after those sessions were completed (Rodent Diet 2018, Harlan, Madison, WI). Subjects ranged in weight from 300–380 g.

Apparatus

Nine identical modular test chambers (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA, Model E10-10TC) described previously (Amato et al., 2012) were used in all experiments. Briefly, the front panel of each chamber was equipped with a houselight, audio speaker, and response lever. Above the lever were three horizontally aligned indicator lamps (Osram Sylvania, Danvers, MA) that served as stimuli, one with a green plastic cap, one with a yellow plastic cap, and one with a red plastic cap. To the left of the lever was a pellet trough, and to the right of the lever was a recessed drinking trough with a 0.1 mL concave liquid reservoir located beneath the trough. A liquid solenoid (Parker Hannifin Corp., New Britain, CT) mounted behind each panel dispensed liquid from a 50-mL centrifuge tube to the liquid reservoir in the chamber when activated. A separate feeder dispensed pellets to the pellet trough. Each chamber was enclosed within a sound-attenuating cubicle equipped with a fan for ventilation and white noise. All test chambers were connected to a computer with MED-PC for Windows, Version IV (MED Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT), which also generated cumulative records for each chamber (Soft CR, MED Associates, Inc.).

Training

Voluntary ethanol intake using either a modified saccharin-fading procedure (Amato et al., 2012), or a home-cage procedure (Hulin et al., 2012) was used prior to shaping the subjects to respond on the lever in each experimental chamber. During initial training sessions, the green stimulus light above the lever was illuminated and every response on the lever dispensed 0.1 mL of 32% v/v ethanol to the liquid reservoir. After rats reliably pressed the lever under this fixed-ratio (FR) 1 schedule, the number of responses necessary for reinforcement was increased until subjects were responding under an FR-10 schedule (i.e., every 10 lever presses dispensed 0.1 mL of 32% v/v ethanol). After 5 days of stable responding under this schedule (in general, the volume of ethanol consumed did not vary by more than 30% from day to day), another component was added to the schedule and strictly alternated with the ethanol component after a specified period of time (i.e., 10 min for ethanol components and 5 min for food components). In this component, the red stimulus light above the lever was illuminated and rats responded under an FR-1 schedule in which a single lever press illuminated the pellet trough briefly (0.4 s) and dispensed a food pellet. To increase stimulus control in each component, the houselight was illuminated during ethanol components and extinguished during food components. As training progressed under this multiple schedule, the number of responses required for food reinforcement was increased until rats were responding under an FR-20 schedule. Each component was also followed by a 1-min resetting change-over delay in which the stimuli above the lever and the houselight were extinguished, and responding on the lever restarted the delay period. The purpose of this manipulation was to limit the development of adventitiously or superstitiously reinforced responding (for an in-depth discussion of adventitious reinforcement, see Sidman, 1960). Sessions began with a 10-min ethanol component and alternated with a 5-min food component each day. For all of the drugs except pregnanolone, sessions ended after 51 min. For pregnanolone, the session timer was removed and the subjects were allowed to complete 4 components under each schedule, which amounted to an increase of approximately 9 min, depending on the amount of responding during the changeover delay. Stable responding for each subject was defined as 10 consecutive days during which responding for food did not vary by more than 20%.

Experiment 1

The acute effects of DHEA (18–133 mg/kg, n = 6), pregnanolone (1–18 mg/kg, n = 9), naltrexone (1–56 mg/kg, n = 5), and acamprosate (32–560 mg/kg, n = 6) were determined after responding under the multiple FR-10 FR-20 schedule had stabilized. In those subjects that received more than one drug (see Table 1 for details), the dose-effect curves for one drug were completed before testing with another drug began. At least 7–10 sessions without drug (i.e., baseline sessions) were also conducted between the end of a series of injections with one drug and the start of a series with another. DHEA, pregnanolone, and naltrexone were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) 15 min prior to the session, while acamprosate was injected i.p. 2 h prior to the session, consistent with an effective time course established in the literature (Hölter et al., 1997). The injection volume was generally 0.1 mL/100 g, except at the higher concentrations due to limitations in solubility (i.e., 56–133 mg/mL of DHEA, 56 mg/mL of naltrexone, and 320–560 mg/mL of acamprosate). DHEA (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO) and pregnanolone (Steraloids, Inc., Newport, RI) were dissolved in a vehicle consisting of 45% (w/v) (2-hydroxyproply)-γ-cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich) and saline. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) and acamprosate sodium (AK Scientific, Inc., Mountain View, CA) were dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline. Drug injections were generally administered on Tuesdays and Fridays, with vehicle or saline (control) injections administered on Thursdays. On one occasion, 320 mg/kg of acamprosate was also administered on 2 consecutive days prior to a test session in order to test its effectiveness after consecutive administrations. Baseline sessions (no injections) were conducted on Mondays and Wednesdays. The highest doses of each drug were only administered once per week to avoid the development of acute tolerance and to limit any “carry over” effects. Doses of each drug were administered in a mixed order.

Table 1.

Doses of DHEA, naltrexone, acamprosate, and pregnanolone that decreased response rate in the food- and ethanol-reinforced components by 50% (ED50) in each subject. Dashes indicate instances in which the response rate was decreased by less than 50%, and thus, an ED50 could not be calculated.

| DHEA ED50 | Naltrexone ED50 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | Food | Ethanol | Food | Ethanol |

| 1172 | 58.3 | 53.3 | 36.2 | 36.6 |

| 1175 | 73.0 | 67.3 | 18.6 | 36.4 |

| 1177 | 64.0 | 59.2 | 34.3 | 33.7 |

| 1185 | 77.3 | 65.2 | ||

| 1187 | 80.7 | 49.8 | ||

| 1190 | 100.9 | 56.5 | 55.6 | 41.2 |

| 1192 | 38.8 | 29.7 | ||

| Mean | 75.7 | 58.6* | 36.7 | 35.5 |

| 95% CI | 60.1–91.3 | 51.4–65.7 | 20.3–53.1 | 30.3–40.8 |

| Acamprosate ED50 | Pregnanolone ED50 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food | Ethanol | Food | Ethanol | |

| 1213 | 244.9 | 97.7 | --- | 13.9 |

| 1214 | --- | --- | ||

| 1215 | --- | --- | 12.6 | 9.4 |

| 1216 | --- | --- | --- | 14.6 |

| 1217 | 331.9 | 331.9 | 8.1 | 8.8 |

| 1218 | --- | --- | ||

| 1219 | 17.1 | 15.9 | ||

| 1220 | --- | --- | 14.8 | 14.2 |

| 1221 | 354.0 | 226.5 | ||

| 1190 | --- | 8.4 | ||

| Mean | 310.3 | 218.7 | 13.2 | 12.2 |

| 95% CI | 167.0–453.5 | 0.0–510.1 | 7.0–19.3 | 9.2–15.1 |

Asterisks (*) indicate a significant difference from food based on the 95% confidence interval (CI).

Experiment 2

Following training under a multiple FR-10 FR-20 schedule for the 9 naïve rats, the schedule of responding for food reinforcement was changed from an FR-20 to a VI-60 and the component duration was increased from 5 to 10 minutes. However, the schedule of responding for ethanol reinforcement remained on an FR-10 schedule and continued to be 10 min in duration. When responding under the VI-60 schedule stabilized, the mean interval value was systematically altered to assess the effect of different intervals for food reinforcement on responding for ethanol. Each interval was in place either until the average volume of ethanol delivered varied by less than 20% across 3 days, or until a maximum of 8 sessions was attained. The mean interval was altered in a mixed order: VI-40, VI-60, VI-20, VI-60, VI-80, VI-40, VI-80, VI-20, VI-60, and VI-80.

Experiment 3

To assess the effects of the four drugs under a multiple schedule that produced similar numbers of ethanol and food reinforcements, an effective dose of each drug was administered subchronically under a multiple FR-10 VI-80 schedule. With the exception of the dose for acamprosate, the dose selected was a dose that significantly affected responding acutely under the multiple FR-10 FR-20 schedule in Experiment 1 (i.e., 56 mg/kg of DHEA, 56 mg of naltrexone, 180 mg/kg of acamprosate, and 5.6 mg/kg of pregnanolone). The dose of acamprosate was reduced because the 560 mg/kg was lethal for one subject, so a dose one-half log unit lower was chosen. In addition, in contrast to Experiment 1, each dose of drug was administered until either ethanol intake did not differ by more than 20% of the mean for 3 consecutive days or for a maximum of 8 days, in which case only the last 3 of those 8 days were averaged for comparability. The pre-session administration time for all of the drugs in this experiment was 15 min.

Blood ethanol concentrations

Blood ethanol concentrations (BECs) were determined following administration of the lowest effective doses of each drug in Experiments 1 and 3, and following all of the changes in mean variable interval in Experiment 2. This was accomplished by saphenous venipuncture immediately following the experimental session in all cases; more specifically, venipuncture occurred on the day the lowest effective dose was redetermined in Experiment 1, whereas venipuncture occurred on the day each subject met criterion in Experiments 2 and 3. All samples were centrifuged (Eppendorf, Model #5418) at 14,000 × g for 5 min and the serum was then harvested and stored at -80 °C until analysis. BECs (mg/dL) were determined using the MicroStat GM7 Analyzer (Analox Instruments Inc., Lunenburg, MA), and the intra-assay coefficient of variation was 4.15 mg/dL.

Data analyses

The dose of ethanol presented was calculated as grams/kilogram (g/kg) body weight based on the volume of solution dispensed and the body weight for each subject. Mean data for each subject were grouped and analyzed using 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA tests with reinforcer and dose (Experiment 1) or reinforcer and VI schedule (Experiment 2) serving as factors. In Experiment 3, a 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to analyze response rate for each drug, with drug and reinforcer serving as factors. One-way ANOVA tests were used to determine the effect of drug administration on the dose of ethanol presented and BEC (Experiment 3). One-way repeated-measures ANOVA tests and Holm-Sidak post hoc tests were also conducted following significant interactions between factors. Significance was accepted at α level ≤ 0.05 for all statistical tests. For the rare occasions when all of the doses of a drug were not administered to every subject in an experimental group (i.e., 133 mg/kg of DHEA), the statistical software (SigmaPlot 12, Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA) defaults to a General Linear Model to accomplish the repeated-measures analysis.

In order to characterize and compare the potency of each drug on food- and ethanol-maintained responding, doses that produced a 50% decrease in rate of responding (ED50 values) for each reinforcer were determined by linear regression using two or more points that represented the slope of the descending portion of the curve. The curves were considered significantly different if the ED50 values for ethanol-maintained responding fell outside the 95% confidence intervals obtained for food-maintained responding.

Results

Operant responding for ethanol was established in all rats. The average volume of ethanol consumed per session under the FR-10 FR-20 schedule of reinforcement was 2.04 ± 0.12 mL, which resulted in an average dose per session of 1.39 ± 0.08 g/kg and BEC of 143.9 ± 5.2 mg/dL. Stable responding under the multiple schedule was also characterized by a distinct pattern of responding in which high, constant rates of responding were followed by brief periods with no responding prior to the initiation of each ratio (i.e., a “break and run” pattern characteristic of responding maintained under an FR schedule).

Experiment 1

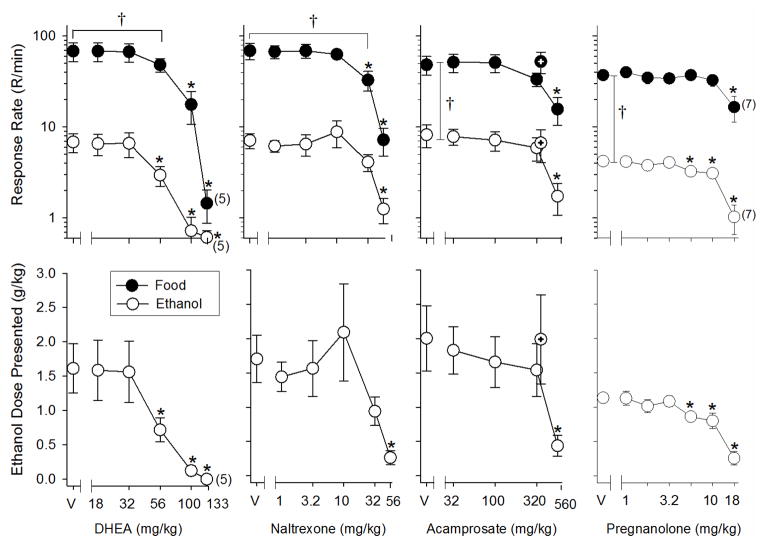

The top left-hand panel of Fig. 1 shows the effects of increasing doses of DHEA on the rate of ethanol- and food-maintained responding under the FR-10 FR-20 schedule. When analyzed statistically, there was a main effect of both dose [F(5,20) = 152.74, p < 0.001] and reinforcer [F(1,4) = 25.48, p = 0.007] on response rate, as well as a significant interaction between these factors [F(5,20) = 16.16, p < 0.001]. On the rate of ethanol-maintained responding, for example, there was a significant main effect of DHEA dose [F(5,24) = 8.99, p < 0.001], and doses of 56–133 mg/kg were significantly different from control (vehicle). On the rate of food-maintained responding, there was also a significant effect of DHEA dose [F(5,24) = 16.93, p < 0.001], but only the effects of 100 and 133 mg/kg were significantly different from control. This difference in potency for the effects of DHEA on food- and ethanol-maintained responding was also indicated by the ED50 values presented in Table 1, as the ED50 for ethanol-maintained responding was significantly lower than that for food.

Figure 1.

Effects of DHEA (n = 6), naltrexone (n = 5), acamprosate (n = 6), and pregnanolone (n = 9) in male rats responding under a multiple schedule of ethanol (FR-10) and food (FR-20) presentation. The dependent measures were response rate (responses [R]/min, top panels) plotted on a log scale and ethanol dose presented (g/kg, bottom panels). For each drug, the unfilled circles represent response rate during the ethanol component, whereas filled circles represent response rate during the food component. The additional points and vertical lines above the 320 mg/kg dose in the acamprosate graph indicate the mean and SEM for a session in which acamprosate was administered acutely over 2 consecutive days. The points and vertical lines above “V” indicate the mean and SEM for sessions in which vehicle was administered (control). The points with vertical lines in the dose-effect data indicate the mean and SEM for sessions in which the respective drugs were administered. The points without vertical lines indicate instances in which the SEM is encompassed by the point. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of subjects represented by that data point when it was less than the total number of subjects for that group, because of the elimination of responding in some subjects at doses below the highest dose tested. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences from control, whereas the bracket and cross (†) indicates significant differences between the response rates for food- and ethanol-maintained behavior.

As shown in the bottom left-hand panel of Fig. 1, the dose of DHEA also had an effect on the dose of ethanol presented [F(5,24) = 9.43, p < 0.001]. Consistent with the effects on response rate, 56–133 mg/kg of DHEA significantly decreased the dose presented when compared to control.

The top panel in the second column of Fig. 1 shows the effects of increasing doses of naltrexone on the rate of ethanol- and food-maintained responding. Similar to DHEA, there was a main effect of naltrexone dose [F(5,20) = 13.78, p < 0.001], a main effect of reinforcer [F(1,4) = 42.88, p = 0.003], and a significant interaction [F(5,20) = 10.46, p < 0.001] of these factors on response rate. However, an analysis of the interaction indicated that food-maintained responding was more sensitive to disruption by naltrexone than ethanol-maintained responding (i.e., 56 mg/kg had a significant effect on the response rate for ethanol [F(5,20) = 5.10, p = 0.004], but both 32 and 56 mg/kg had a significant effect on the response rate for food [F(5,20) = 12.38, p < 0.001]. Consistent with the response rate data, the bottom panel for naltrexone shows that only 56 mg/kg of naltrexone significantly affected the dose of ethanol presented when compared to control [F(5,20) = 5.24, p = 0.003]. Although the statistical analyses indicated there was a difference in potency for the effects of naltrexone on ethanol- and food-maintained response rates, the ED50 values shown in Table 1 were not significantly different.

Analyses of the acamprosate data indicated there was a significant main effect of acamprosate dose [F(4,32) = 5.61, p = 0.002], type of reinforcer [F(1,8) = 26.42, p < 0.001], and a significant interaction [F(4,32) = 3.43, p = 0.02] between these factors on response rate (third column, Fig. 1). Furthermore, the dose of acamprosate significantly affected responding for each reinforcer, with 560 mg/kg producing significant differences from control [ethanol: F(4,32) = 7.37, p < 0.001; food: F(4,32) = 4.56, p = 0.005]. This similarity in potency also resulted in response rates for food and ethanol that were significantly different at every dose tested (p < 0.05). Although there was a difference in the ED50 values of almost 100 mg/kg, this difference was not significant, likely due to the small number of subjects in which a 50% decrease in response rate was produced. Note as well that administering 320 mg/kg of acamprosate over 2 consecutive days did not significantly alter the response rate for either reinforcer compared to control.

The bottom panel for acamprosate depicts the effects of acamprosate on the dose of ethanol presented. Similar to the effects on response rate, the dose of acamprosate significantly affected the dose of ethanol presented [F(4,20) = 4.108, p < 0.014], and 560 mg/kg of acamprosate differed significantly from control.

In the group that received pregnanolone (right-most top panel of Fig. 1), the statistical analyses indicated there was a significant effect of reinforcer [F(1,6) = 48.25, p < 0.001] and dose [F(6,36) = 9.85, p < 0.001] on response rate, and a significant interaction [F(6,36) = 6.44, p < 0.001]. Further analysis of the interaction indicated that 5.6–18 mg/kg of pregnanolone significantly affected ethanol-maintained response rates [F(6,46) = 22.00, p < 0.001], whereas only 18 mg/kg affected food-maintained response rates [F(6,46) = 7.06, p < 0.001] compared with control. Nevertheless, the dose-effect curves for response rate did not converge at the highest dose (i.e., the response rates for both food and ethanol were significantly different from one another at every dose tested (p < 0.05), and the ED50 values for ethanol- and food-maintained responding were not significantly different (Table 1). The bottom right-hand panel shows that the doses of pregnanolone that significantly decreased the response rate for ethanol (i.e., 5.6–18 mg/kg) also significantly decreased the dose of ethanol presented [F(6,46) = 20.49, p < 0.001].

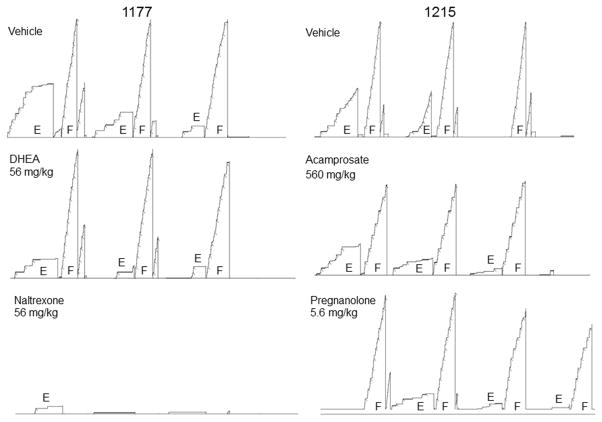

Fig. 2 depicts cumulative records from two representative subjects demonstrating the within-session pattern of responding in each component under the multiple FR-10 FR-20 schedule. As shown, following a saline or vehicle (control) injection (top row), the majority of ethanol-maintained responding occurs during the first component, whereas food-maintained responding generally remains stable throughout the session. When the lowest effective dose of each drug was administered, however, the patterns of responding varied with the drug. For example, DHEA and pregnanolone rather selectively decreased ethanol-maintained responding without affecting food-maintained responding, whereas naltrexone and acamprosate decreased responding for both reinforcers compared with responding after control injections. In fact, 56 mg/kg of naltrexone virtually eliminated responding in both components in subject 1177.

Figure 2.

Cumulative records from subjects 1177 (left) and 1215 (right) showing the within-session pattern of responding under an alternating schedule of ethanol- and food-maintained responding after a control injection (top records). The effects of DHEA (56 mg/kg), naltrexone (56 mg/kg), acamprosate (560 mg/kg), and pregnanolone (5.6 mg/kg) on this pattern of responding are also shown. In each component, the response pen stepped upward with every response and was deflected (‘pipped’) downward after reinforcement. The response pen reset at the edge of the paper or at the completion of a component. Ethanol components alternated after 10 min, whereas food components alternated after 5 min. Session duration was 51 min for DHEA, naltrexone, and acamprosate. Session duration for pregnanolone was approximately 60 min or slightly longer, depending on responding during the changeover delay, which allowed for the extra food component for this drug.

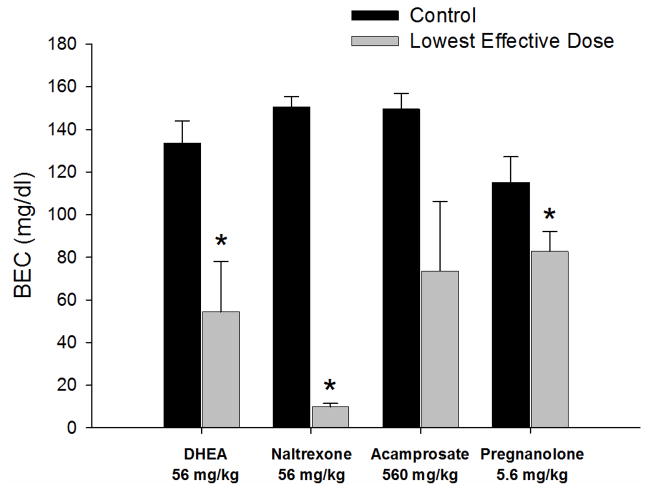

Fig. 3 shows BEC data for the lowest effective dose of each drug (i.e., 56 mg/kg for DHEA and naltrexone, 5.6 mg/kg for pregnanolone, and 560 mg/kg for acamprosate). Based on a 2-way ANOVA, there were no significant differences among the drugs [F(3,42) = 1.12, p = 0.351], but there was a significant effect of dose for all of the drugs [F(1,42) = 51.56] and a significant interaction of drug and dose [F(3,42) = 4.16, p = 0.011]. Subsequent analyses of the interaction then indicated that BECs following DHEA [F(1,8) = 9.39, p = 0.015], naltrexone [F(1,8) = 779.54, p < 0.001], and pregnanolone [F(1,16) = 4.57, p = 0.048] were all significantly different from control. The only drug for which the lowest effective dose did not significantly affect BEC was acamprosate [F(1,10) = 4.87, p = 0.052].

Figure 3.

Blood ethanol concentration (BEC) data for rats responding under a multiple FR-10 FR-20 schedule of ethanol and food presentation. Black bars represent BEC data collected after control sessions, whereas grey bars represent BEC data collected after the second determination of the lowest effective dose of DHEA (56 mg/kg, n = 6), naltrexone (56 mg/kg, n = 5), acamprosate (560 mg/kg, n = 6), and pregnanolone (5.6 mg/kg, n = 9). All bars and vertical lines represent the mean and SEM for the subjects in each drug group. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences from the respective control (p < 0.05).

Experiment 2

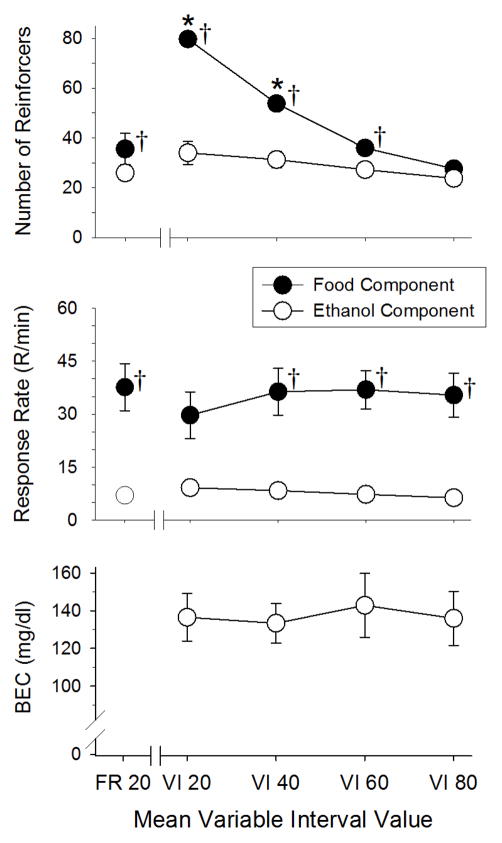

Fig. 4 shows the effects of different mean interval values (in sec) of food reinforcement on both food- and ethanol-maintained responding under multiple FR VI schedules. More specifically, the effects were assessed on the number of reinforcements (top panel), response rate (middle panel), and BEC (bottom panel). The data in the left-hand portion of each graph above “FR 20” were collected under the multiple FR FR schedule just prior to initiating the multiple FR VI schedules and are presented for comparison purposes. As indicated by the data in the top panel, increasing the mean interval value significantly decreased the number of food reinforcers obtained while having no significant effect on the number of ethanol reinforcers obtained. This was verified statistically by a significant interaction between the schedule and reinforcer [F(4,28) = 27.27, p < 0.001]. Post hoc analyses of the interaction also indicated that the number of food reinforcers obtained when the mean interval values were 20 and 40 was significantly different from the number of reinforcers obtained under the original FR-20 schedule. Furthermore, the number of food and ethanol reinforcers obtained between components was significantly different under the multiple FR FR schedule, as well as under all of the VI schedules except the VI-80 schedule.

Figure 4.

Effects of different mean variable interval values on the number of food and ethanol reinforcements (top panel), response rate (middle panel), and BEC (bottom panel) in 8 rats responding under a multiple schedule of ethanol (FR-10) and food (VI) presentation. Unfilled circles with vertical lines represent the mean and SEM for these dependent measures in the ethanol component, whereas filled circles with vertical lines represent the mean and SEM for these measures in the food component. The points without vertical lines indicate instances in which the SEM is encompassed by the point. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences between the number of reinforcers obtained under the various VI schedules of food reinforcement and the number of reinforcers obtained under the FR schedule. Crosses (†) indicate significant differences between food- and ethanol-maintained responding in terms of the number of reinforcers obtained or the overall response rate.

The middle panel of Fig. 4 also indicates that increasing the mean interval value had little or no effect on the response rate in the food-maintained VI component or the response rate in the ethanol-maintained FR component. This was verified by a significant main effect of reinforcer [F(1,7) = 13.04, p = 0.009] and a significant interaction between schedule and reinforcer [F(4,28) = 4.24, p = 0.008], but the absence of a main effect for schedule [F(4,28) = 0.23, p = 0.92]. In other words, comparatively high rates occurred for food regardless of the schedule (FR or VI) and these rates were always greater than the rates for ethanol under a FR schedule. As indicated by the significant interaction, the only exception to this trend occurred under the VI-20 schedule, which abolished the significant difference between the response rates for each reinforcer.

Because the increase in mean interval value had no significant effects on ethanol-maintained responding under the FR schedule, BEC remained stable under the different VI schedules (bottom panel of Fig. 4). For example, mean BEC values ranged from 133 (VI-40) to 142 (VI-60) mg/dL, and not surprisingly, a 1-way ANOVA indicated that there was no significant effect of mean interval value on BEC [F(3,21) = 0.15, p > 0.05].

Experiment 3

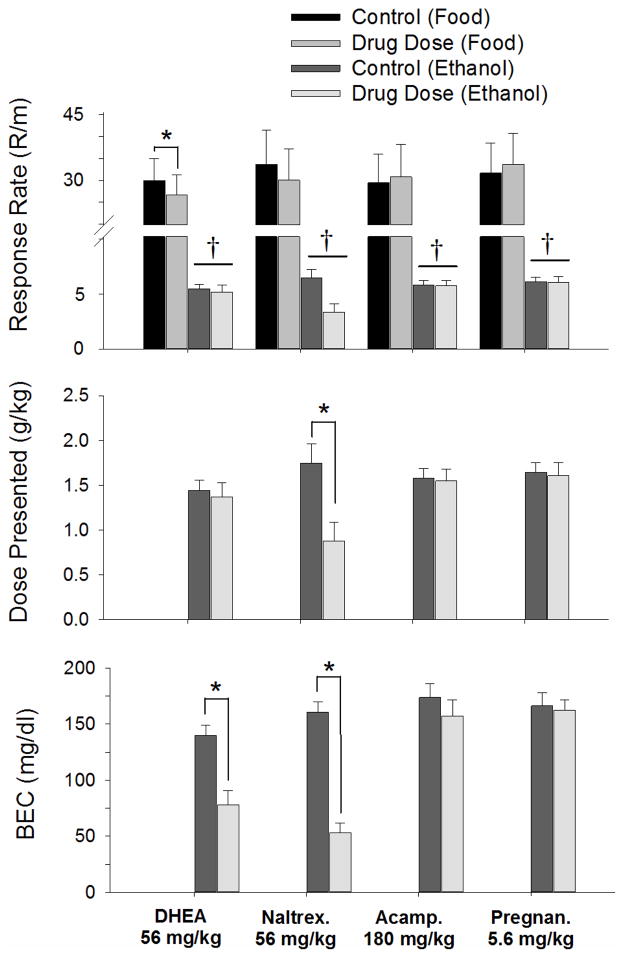

Fig. 5 shows the effects of each drug on response rate for both ethanol and food reinforcement under the multiple FR-10 VI-80 schedule. With the exception of acamprosate, the dose selected was the lowest dose to produce a significant effect under the multiple FR-10 FR-20 schedule. As additional dependent measures of the effects of each drug on ethanol-maintained responding, the dose presented as well as BEC were also measured. With respect to response rate, none of the drugs altered the significant difference between the response rates for food and ethanol, as indicated by a significant effect of reinforcer for each drug [DHEA, F(1,7) = 21.36, p = 0.002; naltrexone, F(1,7) = 12.89, p = 0.009; acamprosate, F(1,7) = 11.72, p = 0.011; and pregnanolone, F(1,7) = 13.72, p = 0.008]. Furthermore, none of the drugs was able to selectively decrease ethanol-maintained responding at the dose tested, as this would have been indicated by a significant interaction [naltrexone, F(1,7) = 0.02, p > 0.05; acamprosate, F(1,7) = 1.94, p > 0.05; and pregnanolone, F(1,7) = 2.64, p > 0.05]. There was a significant interaction between drug and reinforcer for DHEA [F(1,7) = 6.77, p = 0.035], but this was because food-maintained responding was significantly decreased compared to control. Also of note, naltrexone was able to decrease ethanol-maintained responding, but it was not significant, largely due to the concomitant decrease in food-maintained responding. Thus, naltrexone did not produce a significant interaction between treatment and reinforce, and the effect of drug did not reach statistical significance [F(1,7) = 3.65, p = 0.098].

Figure 5.

Effects of a single dose of DHEA, naltrexone, acamprosate, and pregnanolone on responding under a multiple schedule of ethanol (FR-10) and food (VI-80) presentation in 9 subjects. Each dose was administered until one of two criteria was met; that is, until either intake did not vary by more than 20% of the mean for 3 days or a total of 8 days, in which case the last 3 of those 8 days were averaged for comparison. The dependent measures were response rate (responses [R]/minute (m), top panel), ethanol dose presented (g/kg, middle panel), and BEC (mg/dL, bottom panel). Bars and vertical lines indicate the grand mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) for the 9 subjects. Asterisks indicate significant differences between drug and control for a particular reinforcer, whereas crosses indicated significant differences between reinforcers (i.e., significant main effects of reinforcer).

The decrease in ethanol-maintained responding after naltrexone was enough, however, to significantly decrease the dose of ethanol presented and BEC (middle and bottom panels of Fig. 5). Following naltrexone, the dose of ethanol presented dropped from an average of 1.75 to 0.88 g/kg, whereas the average BEC dropped from 160.9 to 53.1 mg/dL. Unlike the effects of naltrexone on the dose of ethanol presented and BEC, acamprosate and pregnanolone were unable to significantly alter these measures. DHEA, on the other hand, did not significantly decrease the dose of ethanol presented, but did significantly decrease BEC from an average of 140.1 to 77.9 mg/dL.

Discussion

Experiment 1 determined the capacity of several drugs to reduce ethanol-reinforced responding in the context of a multiple schedule of ethanol and food reinforcement. Interestingly, the two experimental neurosteroids (DHEA and pregnanolone) were the only drugs that selectively reduced ethanol-reinforced responding, and each did so in a direct comparison with a drug that is currently used to treat alcohol abuse and dependence. Experiment 2 demonstrated the relative independence of ethanol- and food-reinforced responding under the multiple schedule by instituting a VI schedule for food reinforcement and showing that ethanol-maintained responding was largely unaffected. These data were important because they strongly suggest that the selective drug effects observed in Experiment 1 were not the result of an interaction between the food and ethanol components of the multiple schedule. Experiment 3 attempted to replicate the selectivity of the drug effects in Experiment 1 under a multiple FR-10 VI-80 schedule, which essentially equated the number of ethanol and food reinforcers that could be obtained. Under these conditions, only naltrexone was capable of significantly decreasing both the dose of ethanol presented and BEC. Somewhat surprisingly, neither DHEA nor pregnanolone was able to selectively decrease ethanol-maintained responding in the same manner as they did in Experiment 1. Possibly even more surprising was the fact that DHEA significantly decreased BEC without decreasing the response rate for ethanol or the dose of ethanol presented.

As mentioned above, only DHEA and pregnanolone decreased responding for ethanol at doses that did not decrease responding for food in Experiment 1. With regard to DHEA, these findings parallel those reported previously by Amato et al. (2012). However, in that study, DHEA significantly decreased BEC without significantly decreasing the mean overall response rate for the group. This occurred largely because responding during the ethanol component became superstitiously “chained” to responding in the food component for a small number of subjects. Following DHEA administration, these subjects responded during the ethanol component without consuming the total amount of ethanol dispensed. In the present experiments, components strictly alternated with time, which increased experimental control over responding for each reinforcer and eliminated such “superstitious responders”. The increased experimental control also led to a closer association between response rate and reinforcer density for all of the subjects. Finally, the DHEA results from the present study provide a systematic replication of those in the previous study (Amato et al., 2012) indicating that DHEA can decrease ethanol-maintained responding more potently than food-maintained responding under a multiple FR FR schedule.

Similar to DHEA, the capacity of pregnanolone to modulate ethanol self-administration was consistent with previous studies involving either pregnanolone (Gurkovskaya et al., 2009) or allopregnanolone, a naturally occurring epimer (Ford, Mark, Nickel, Phillips, & Finn, 2007; Ford, Nickel, Phillips, & Finn, 2005; Janak, Redfern, & Samson, 1998; Sinnott, Phillips, & Finn, 2002). In general, these two epimers have been shown to increase ethanol intake at intermediate doses, while decreasing intake at higher doses in both rats and mice. However, these effects likely depend on a number of pharmacological and behavioral variables, and they are not consistently produced by all of the different types of positive GABAA receptor modulators (e.g., Amato et al., 2012; Janak, Redfern, & Samson, 1998; Leonard, Gerak, Gurkovskaya, Moerschbaecher, & Winsauer, 2006). With respect to the pregnane steroids, for example, intermediate doses of pregnanolone did not increase operant responding for ethanol in the present study involving rats, but intermediate doses of allopregnanolone did increase operant responding for ethanol after both i.p. and intracerebroventricular administration in mice (Ford et al., 2005, 2007). Furthermore, in a study from our laboratory using a 2-bottle preference test with rats, an intermediate dose (i.e., 3.2 mg/kg) of pregnanolone increased ethanol intake compared to control after a single acute injection, but not after multiple (3 to 8) injections (Gurkovskaya et al., 2009). The many ways in which ethanol and the neurosteroids can interact also complicates the understanding of how pregnanolone or allopregnanolone affects ethanol intake. Ethanol has been shown to increase the plasma and brain concentrations of allopregnanolone (Barbaccia et al., 1999), and it can modulate both GABAA receptor subunit expression (Kumar, Fleming, & Morrow, 2004) as well as the interaction of endogenous neuroactive steroids with specific GABAA receptor subtypes (Akk, Li, Manion, Evers, & Steinbach, 2007).

Regardless of the exact mechanism by which the pregnane steroids decrease ethanol intake, the selectivity of pregnanolone for reducing ethanol-reinforced responding gives further credence to the notion that substances of this type could potentially serve as pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse and dependence (Ford et al., 2007; VanDoren et al., 2000). Given the opposing ways in which pregnanolone and DHEA interact with the GABAA receptor complex, however, pregnanolone would likely serve more as a “substitution” therapy than DHEA. Consistent with this notion are data from this laboratory and others demonstrating that pregnanolone and other 3α-hydroxy neurosteroids have largely overlapping discriminative stimulus effects with ethanol (Bowen, Purdy, & Grant, 1999; Gerak, Moerschbaecher, & Winsauer, 2008; Ginsburg & Lamb, 2005), whereas DHEA and its sulfated form do not (Bienkowski & Kostowski, 1997; Gurkovskaya & Winsauer, 2009). There are also published data indicating that pregnanolone has reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects in monkeys similar to the barbiturates, another class of drugs that positively modulate the GABAA receptor complex (Rowlett et al., 1999). A final limitation of pregnanolone may be that it was not as effective as DHEA at reducing ethanol intake in a 2-bottle preference test after multiple administrations (Gurkovskaya et al., 2009).

Although clinical trials have indicated that both naltrexone and acamprosate are effective for treating alcohol dependence and preventing relapse (Rösner et al., 2010; Volpicelli, Alterman, Hayashida, & O’Brien, 1992), neither naltrexone nor acamprosate selectively decreased ethanol-maintained responding at the doses tested under the multiple FR FR schedule. The lack of selectivity of naltrexone and acamprosate as well as the need for relatively large doses of these drugs to decrease ethanol intake was consistent with the literature (Escher & Mittleman, 2006). For naltrexone in particular, the effective dose was markedly larger than the dose necessary to block μ-opioid receptors in either rats (e.g., Walker, Makhay, House, & Young, 1994) or monkeys (e.g., France, de Costa, Jacobson, Rice, & Woods, 1990), which suggests that the effect on ethanol- and food-maintained responding was likely mediated by receptors other than the μ-opioid receptors. The effects of naltrexone on ethanol intake in rats have been shown to be variable based on route of administration, drinking paradigm, and even subject food-deprivation levels. For instance, subcutaneous dosing similar to that reported in Gonzales & Weiss (1998) has been shown to be up to 30-fold more potent than intraperitoneal dosing of naltrexone (Williams & Broadbridge, 2009). Furthermore, in studies that directly compared the effects of opioid antagonists on consummatory behavior in food-restricted rats versus free-feeding rats, the opioid antagonist naloxone was at least 10-fold less potent in food-restricted rats (Rudski, Billington, & Levine, 1994). In a study by Williams (2007), intraperitoneal doses of naltrexone up to 30 mg/kg were found to have only a small effect on operant responding for ethanol in food-restricted rats. The use of larger doses may also have been required in the present study to elicit an acute effect, as many previous studies examined the effects of multiple administrations of naltrexone or acamprosate. For example, 3 mg/kg of naltrexone for 3 consecutive sessions was effective at decreasing ethanol intake, whereas 50, 100, or 200 mg/kg of acamprosate for 2 consecutive sessions was effective at decreasing operant ethanol intake (Bienkowski et al., 1999; Czachowski et al., 2001). Thus, multiple administrations or subchronic administration of these drugs may increase the effectiveness of lower doses, as is the case with DHEA. In a study by Gurkovskaya et al. (2009), DHEA doses as low as 10 mg/kg significantly decreased ethanol intake in a 2-bottle ethanol preference procedure after subchronic administration. The fact that DHEA was effective after multiple administrations may be important eventually as the acute effects are probably less critical than the chronic effects for treating dependence. In the meantime, DHEA will need to be compared to naltrexone and acamprosate in other experimental situations and on ethanol reinstatement, as such studies would be another valuable means of determining the putative effectiveness of DHEA for treating alcohol abuse and dependence.

In light of the superstitious behavior that developed previously in some subjects under a multiple FR-10 FR-20 schedule (Amato et al., 2012), the purpose of Experiment 2 was to examine the potential interaction of these schedule components. The schedule of reinforcement and the differential response rates generated by each reinforcer are two variables among many that have been shown to affect both drug self-administration (Kelleher & Goldberg, 1975; Meisch, 1987, 2001) and the behavioral effects of drugs (Barrett & Stanley, 1980; Kelleher & Morse, 1968). Changing the schedule of reinforcement from an FR to a VI during the food component lowered rates of food reinforcement while also producing substantial reductions in the number of food reinforcers obtained during a session. Specifically, as the mean variable interval value increased, food reinforcements decreased. Under the VI-80 schedule, for example, the number of food reinforcements was similar to the number of reinforcements under the FR-20 schedule for food and to the number of ethanol reinforcers under the FR-10 schedule. Despite these orderly changes in the density of food reinforcement under the VI schedules, there was no significant effect on responding during the ethanol component, indicating the relative independence of the responding for each reinforcer under these multiple schedule parameters.

As mentioned earlier, the failure of DHEA and pregnanolone to selectively lower ethanol-maintained responding under the multiple FR-10 VI-80 schedule was somewhat surprising given their effects in several previous studies (Amato et al., 2012; Gurkovskaya et al., 2009; Hulin et al., 2012), and the demonstration of these effects for both home-cage (voluntary) and operant (conditioned) intake procedures. Even without the knowledge gained from these studies, obtaining more potent drug-induced decreases under the ratio schedule for ethanol than the interval schedule for food would not have been surprising. In all likelihood, the sensitivity of the FR component to the marked rate-decreasing effects of naltrexone at 56 mg/kg was responsible for its capacity to significantly decrease both the dose of ethanol presented and BEC in Experiment 3. Interestingly, the rate-decreasing effects of naltrexone under the VI schedule were not large enough to yield a significant main effect of drug on each reinforcer, or small enough to yield a significant interaction between naltrexone and ethanol. Thus, the effects of naltrexone on ethanol-maintained behavior were enhanced under conditions where maintaining the rate of ethanol reinforcement required greater behavioral momentum than maintaining the rate of reinforcement for another reinforcer such as food (cf. Nevin et al., 1983). Although interpreted differently, naltrexone produced similar results in a study by Hay, Jennings, Zitsman, Hodge, & Robinson (2013).

This explanation does not seem to apply to DHEA and pregnanolone, however, as both of these drugs had less of an effect on ethanol-maintained responding under the multiple FR-10 VI-80 schedule than under the multiple FR-10 FR-20 schedule. One possibility is that changing the schedule for food reinforcement from an FR to VI schedule reduced the schedule control over the behavior for that reinforcer and made it more susceptible to disruption than ethanol-maintained behavior (Dews, 1955). A decrease in schedule control under the VI schedule may also explain why the negative GABAA modulator DHEA and the positive GABAA modulator pregnanolone tended to produce effects on food-maintained responding that were not observed previously. More specifically, DHEA significantly decreased food-maintained responding, whereas pregnanolone produced small increases in food-maintained responding, albeit nonsignificantly. These effects are consistent with data indicating that negative modulators such as DHEA produce hypophagic effects (Porter & Svec, 1995), and positive modulators such as pregnanolone produce hyperphagic effects (Chen, Rodriguez, Davies, & Loew, 1996); however, they may have been less observable under a FR schedule. In any case, the drug data obtained using the 2 multiple schedules would seem to indicate that the potency (and possibly the effectiveness) of each drug for decreasing ethanol-maintained behavior can be altered by the schedules of reinforcement, and that further testing under the multiple FR-10 VI-80 schedule will be needed to determine if higher doses of each drug can restore the selective effects observed in earlier studies. Additional studies will also be necessary to determine how DHEA decreased BEC without significantly decreasing the responding for ethanol. As there was no evidence of the type of superstitious chaining that was observed in the previous study (Amato et al., 2012), this effect suggests that DHEA can increase the metabolism of ethanol. However, we have been unable to demonstrate this type of metabolic effect with DHEA in the past (unpublished data).

Future studies will also need to focus on DHEA-related compounds as opposed to DHEA, which is likely to have limited clinical utility in humans due to its androgenic effects (Lardy, Marwah, & Marwah, 2005; Mo, Lu, Garippa, Brownstein, & Simon, 2009; Worrel, Gurkovskaya, Leonard, Lewis, & Winsauer, 2011). Administration of exogenous DHEA has been found to cause acne, hirsutism, and altered menses in women because of its capacity for increasing testosterone levels (Panjari & Davis, 2007; van Vollenhoven, Park, Genovese, West, & McGuire, 1999). However, some of these limitations have been tempered by research indicating that analogues of DHEA such as 7-keto DHEA, which are not converted to sex hormones, are also capable of decreasing ethanol intake (Amato et al., 2012; Worrel et al., 2011). Preclinical laboratory studies have determined that 7-keto DHEA decreases voluntary, home-cage ethanol intake (Panjari & Davis, 2007) and decreases operant responding maintained under a multiple schedule of food and ethanol reinforcement, albeit non-selectively (Amato et al., 2012). There is also the possibility that other metabolites or analogues of DHEA would effectively decrease ethanol intake. 7-keto DHEA contains a keto group at the 7 position of the molecular structure, but modifications of the 3rd and 17th positions of the structure might also produce viable treatments for alcohol abuse (Davidson et al., 2000; Lardy et al., 2005).

In summary, the present findings highlight the value of using multiple schedules of ethanol- and food-maintained responding in the search for new pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse and dependence. These data also support the need for further study of analogues of the neurosteroids as potential pharmacotherapies, because DHEA and pregnanolone were more selective than naltrexone and acamprosate at decreasing ethanol-reinforced responding under a multiple FR FR schedule of ethanol and food reinforcement in rats. Unfortunately, they were not as selective at decreasing ethanol-maintained behavior under the multiple FR VI schedule, but this may have been due to several experimental variables, including the schedule of reinforcement, or simply, the dose of drug tested. The data obtained under the different multiple schedules also highlight the value of studying behavioral variables such as the schedule of reinforcement, as these variables readily show differences in the capacity of both existing and potential pharmacotherapies to decrease ethanol-maintained responding. Furthermore, as suggested by some investigators (e.g., Escher & Mittleman, 2006; Howell & Wilcox, 2001), the most effective pharmacotherapies for drug self-administration are those that can selectively alter one behavior while leaving others intact. If this is the case, both the androstane steroids and the pregnane steroids may hold promise; however, only the androstane steroids do not appear to have an inherent abuse liability.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grant AA019848 (M.W.H.) from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). The NIAAA had no further involvement than financial support. All authors have contributed to the conception of experiments, collection of data, analyses of the results described in this manuscript, and have made significant intellectual contribution to this work. Additionally, the authors have reviewed this final work and approve submission for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors also deny any financial, personal, or other conflicts of interest that may inappropriately affect or influence the presentation or interpretation of the findings described in this manuscript. Finally, the authors would like to express their gratitude for the expert assistance of Mr. Peter B. Lewis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akk G, Li P, Manion BD, Evers AS, Steinbach JH. Ethanol modulates the interaction of the endogenous neurosteroid allopregnanolone with the alpha1beta2gamma2L GABAA receptor. Molecular Pharmacology. 2007;71:461–472. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato RJ, Hulin MW, Winsauer PJ. A comparison of dehydroepiandrosterone and 7-keto dehydroepiandrosterone with other drugs that modulate ethanol intake in rats responding under a multiple schedule. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2012;23:250–261. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32835342d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the effects of allopregnanolone on yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;107:264–267. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Carroll ME. Females are more vulnerable to drug abuse than males: evidence from preclinical studies and the role of ovarian hormones. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 2011;8:73–96. doi: 10.1007/7854_2010_93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaccia ML, Affricano D, Trabucchi M, Purdy RH, Colombo G, Agabio R, et al. Ethanol markedly increases “GABAergic” neurosteroids in alcohol-preferring rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;384:R1–R2. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00678-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JE, Stanley JA. Effects of ethanol on multiple fixed-interval fixed-ratio schedule performances: dynamic interactions at different fixed-ratio values. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1980;34:185–198. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1980.34-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski P, Kostowski W. Discriminative stimulus properties of ethanol in the rat: effects of neurosteroids and picrotoxin. Brain Research. 1997;753:348–352. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski P, Kostowski W, Koros E. Ethanol-reinforced behaviour in the rat: effects of naltrexone. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;374:321–327. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boismare F, Daoust M, Moore N, Saligaut C, Lhuintre JP, Chretien P, et al. A homotaurine derivative reduces the voluntary intake of ethanol by rats: are cerebral GABA receptors involved? Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1984;21:787–789. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(84)80020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen CA, Purdy RH, Grant KA. Ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of endogenous neuroactive steroids: effect of ethanol training dose and dosing procedure. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1999;289:405–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell UC, Carroll ME. Reduction of drug self-administration by an alternative non-drug reinforcer in rhesus monkeys: magnitude and temporal effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;147:418–425. doi: 10.1007/s002130050011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr KD. Feeding, drug abuse, and the sensitization of reward by metabolic need. Neurochemical Research. 1996;21:1455–1467. doi: 10.1007/BF02532386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Boe IN. Effect of dose on increased etonitazene self-administration by rats due to food deprivation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;82:151–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00427762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Rodefer JS, Rawleigh JM. Concurrent self-administration of ethanol and an alternative nondrug reinforcer in monkeys: effects of income (session length) on demand for drug. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02246139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Stotz DC, Kliner DJ, Meisch RA. Self-administration of orally-delivered methohexital in rhesus monkeys with phencyclidine or pentobarbital histories: effects of food deprivation and satiation. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1984;20:145–151. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(84)90115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SW, Rodriguez L, Davies MF, Loew GH. The hyperphagic effect of 3 alpha-hydroxylated pregnane steroids in male rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1996;53:777–782. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove KP, Carroll ME. Effects of a non-drug reinforcer, saccharin, on oral self-administration of phencyclidine in male and female rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;170:9–16. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czachowski CL, Delory MJ. Acamprosate and naltrexone treatment effects on ethanol and sucrose seeking and intake in ethanol-dependent and nondependent rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;204:335–348. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1465-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czachowski CL, Legg BH, Samson HH. Effects of acamprosate on ethanol-seeking and self-administration in the rat. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:344–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czachowski CL, Samson HH, Denning CE. Independent ethanol- and sucrose-maintained responding on a multiple schedule of reinforcement. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:398–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson M, Marwah A, Sawchuk RJ, Maki K, Marwah P, Weeks C, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetic study with escalating doses of 3-acetyl-7-oxo-dehydroepiandrosterone in healthy male volunteers. Clinical and Investigative Medicine. 2000;23:300–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dews PB. Studies on behavior. I. Differential sensitivity to pentobarbital of pecking performance in pigeons depending on the schedule of reward. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1955;113:393–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escher T, Mittleman G. Schedule-induced alcohol drinking: non-selective effects of acamprosate and naltrexone. Addiction Biology. 2006;11:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferster CB, Skinner BF. Schedules of Reinforcement. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Ford MM, Mark GP, Nickel JD, Phillips TJ, Finn DA. Allopregnanolone influences the consummatory processes that govern ethanol drinking in C57BL/6J mice. Behavioural Brain Research. 2007;179:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford MM, Nickel JD, Phillips TJ, Finn DA. Neurosteroid modulators of GABA(A) receptors differentially modulate Ethanol intake patterns in male C57BL/6J mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1630–1640. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000179413.82308.6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France CP, de Costa BR, Jacobson AE, Rice KC, Woods JH. Apparent affinity of opioid antagonists in morphine-treated rhesus monkeys discriminating between saline and naltrexone. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1990;252:600–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerak LR, Moerschbaecher JM, Winsauer PJ. Overlapping, but not identical, discriminative stimulus effects of the neuroactive steroid pregnanolone and ethanol. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2008;89:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg BC, Koek W, Javors MA, Lamb RJ. Effects of fluvoxamine on a multiple schedule of ethanol- and food-maintained behavior in two rat strains. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:249–257. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2156-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg BC, Lamb RJ. Alphaxalone and epiallopregnanolone in rats trained to discriminate ethanol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1621–1629. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000179374.39554.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales RA, Weiss F. Suppression of ethanol-reinforced behavior by naltrexone is associated with attenuation of the ethanol-induced increase in dialysate dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:10663–10671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10663.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurkovskaya OV, Leonard ST, Lewis PB, Winsauer PJ. Effects of pregnanolone and dehydroepiandrosterone on ethanol intake in rats administered ethanol or saline during adolescence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Alcoholism Research. 2009;33:1252–1264. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurkovskaya OV, Winsauer PJ. Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol, pregnanolone, and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in rats administered ethanol or saline as adolescents. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2009;93:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Spealman R. Controversies in translational research: drug self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:403–419. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1079-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay RA, Jennings JH, Zitzman DL, Hodge CW, Robinson DL. Specific and nonspecific effects of naltrexone on goal-directed and habitual models of alcohol seeking and drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Alcoholism Research. 2013;37:1100–1110. doi: 10.1111/acer.12081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyser CJ, Moc K, Koob GF. Effects of naltrexone alone and in combination with acamprosate on the alcohol deprivation effect in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1463–1471. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyser CJ, Schulteis G, Durbin P, Koob GF. Chronic acamprosate eliminates the alcohol deprivation effect while having limited effects on baseline responding for ethanol in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18:125–133. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölter SM, Landgraf R, Zieglgänsberger W, Spanagel R. Time course of acamprosate action on operant ethanol self-administration after ethanol deprivation. Alcoholism: Clinical and Alcoholism Research. 1997;21:862–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Wilcox KM. The dopamine transporter and cocaine medication development: drug self-administration in nonhuman primates. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2001;298:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulin MW, Amato RJ, Winsauer PJ. GABA(A) receptor modulation during adolescence alters adult ethanol intake and preference in rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Alcoholism Research. 2012;36:223–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyytia P, Sinclair JD. Responding for oral ethanol after naloxone treatment by alcohol-preferring AA rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Alcoholism Research. 1993;17:631–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janak PH, Redfern JE, Samson HH. The reinforcing effects of ethanol are altered by the endogenous neurosteroid, allopregnanolone. Alcoholism: Clinical and Alcoholism Research. 1998;22:1106–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RT, Goldberg SR. Control of drug-taking behavior by schedules of reinforcement. Pharmacological Reviews. 1975;27:291–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RT, Morse WH. Determinants of the specificity of behavioral effects of drugs. Ergebnisse der Physiologie, Biologischen Chemie und Experimentellen Pharmakologie. 1968;60:1–56. doi: 10.1007/BFb0107250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleven MS, Woolverton WL. Effects of bromocriptine and desipramine on behavior maintained by cocaine or food presentation in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990;101:208–213. doi: 10.1007/BF02244128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliner DJ, Meisch RA. Oral pentobarbital intake in rhesus monkeys: effects of drug concentration under conditions of food deprivation and satiation. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1989;32:347–354. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Fleming RL, Morrow AL. Ethanol regulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptors: genomic and nongenomic mechanisms. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2004;101:211–226. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardy H, Marwah A, Marwah P. C(19)-5-ene steroids in nature. Vitamins and Hormones. 2005;71:263–299. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(05)71009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Magnen J, Tran G, Durlach J, Martin C. Dose-dependent suppression of the high alcohol intake of chronically intoxicated rats by Ca-acetyl homotaurinate. Alcohol. 1987;4:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(87)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard ST, Gerak LR, Gurkovskaya O, Moerschbaecher JM, Winsauer PJ. Effects of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid and flunitrazepam on ethanol intake in male rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2006;85:780–786. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucki I, DeLong RE. Control rate of response or reinforcement and amphetamine’s effect on behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1983;40:123–132. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1983.40-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhail RC, Gollub LR. Separating the effects of response rate and reinforcement frequency in the rate-dependent effects of amphetamine and scopolamine on the schedule-controlled performance of rats and pigeons. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1975;194:332–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason BJ, Ownby RL. Acamprosate for the treatment of alcohol dependence: a review of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. CNS Spectrums. 2000;5:58–69. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900012827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisch RA. Factors controlling drug reinforced behavior. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1987;27:367–371. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(87)90584-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisch RA. Oral drug self-administration: an overview of laboratory animal studies. Alcohol. 2001;24:117–128. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisch RA, Lemaire GA. Effects of feeding condition on orally delivered ethanol as a reinforcer for rhesus monkeys. Alcohol. 1991;8:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(91)91264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Kamien JB, Lukas SE, Drieze J, Mendelson JH. The effects of nalbuphine and butorphanol treatment on cocaine and food self-administration by rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;8:45–55. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middaugh LD, Kelley BM, Cuison ER, Jr, Groseclose CH. Naltrexone effects on ethanol reward and discrimination in C57BL/6 mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:456–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Q, Lu S, Garippa C, Brownstein MJ, Simon NG. Genome-wide analysis of DHEA- and DHT-induced gene expression in mouse hypothalamus and hippocampus. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2009;114:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevin JA, Mandell C, Atak JR. The analysis of behavioral momentum. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1983;39:49–59. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1983.39-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Berrettini WH, O’Brien CP. Targeting treatments for alcohol dependence: the pharmacogenetics of naltrexone. Addiction Biology. 2006;11:397–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panjari M, Davis SR. DHEA therapy for women: effect on sexual function and wellbeing. Human Reproduction Update. 2007;13:239–248. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati HM, Rabinowitz AR. Choosing the right medication for the treatment of alcoholism. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2006;8:383–388. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JR, Svec F. DHEA diminishes fat food intake in lean and obese Zucker rats. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1995;774:329–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb17400.x-i1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rösner S, Hackl-Herrwerth A, Leucht S, Lehert P, Vecchi S, Soyka M. Acamprosate for alcohol dependence. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;8:CD004332. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004332.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Peselow E. Pharmacotherapy of addictive disorders. Clinical Neuropharmacology. 2009;32:277–289. doi: 10.1097/wnf.0b013e3181a91655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlett JK, Winger G, Carter RB, Wood PL, Woods JH, Woolverton WL. Reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects of the neuroactive steroids pregnanolone and Co 8-7071 in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;145:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s002130051050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudski JM, Billington CJ, Levine AS. Naloxone’s effects on operant responding depend upon level of deprivation. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1994;49:377–383. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90437-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Doyle TF. Oral ethanol self-administration in the rat: effect of naloxone. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1985;22:91–99. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90491-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Roehrs TA, Tolliver GA. Ethanol reinforced responding in the rat: a concurrent analysis using sucrose as the alternate choice. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1982;17:333–339. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz-Stevens KS, Files FJ, Samson HH. Effects of morphine and naloxone on ethanol- and sucrose-reinforced responding in nondeprived rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16:822–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahan TA, Burke KA. Ethanol-maintained responding of rats is more resistant to change in a context with added non-drug reinforcement. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2004;15:279–285. doi: 10.1097/01.fbp.0000135706.93950.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL, Grant KA. Effects of naltrexone and Ro 15-4513 on a multiple schedule of ethanol and Tang self-administration. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1576–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. In Tactics of Scientific Research: Evaluating Experimental Data in Psychology. Boston, MA: Authors Cooperative, Inc; 1960. Control Techniques; pp. 341–363. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott RS, Phillips TJ, Finn DA. Alteration of voluntary ethanol and saccharin consumption by the neurosteroid allopregnanolone in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;162:438–447. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slawecki CJ, Hodge CW, Samson HH. Dopaminergic and opiate agonists and antagonists differentially decrease multiple schedule responding maintained by sucrose/ethanol and sucrose. Alcohol. 1997;14:281–294. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(96)00153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Hölter SM, Allingham K, Landgraf R, Zieglgänsberger W. Acamprosate and alcohol: I. Effects on alcohol intake following alcohol deprivation in the rat. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;305:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg MF, Mackler SA, Volpicelli JR, O’Brien CP. Effect of acamprosate and naltrexone, alone or in combination, on ethanol consumption. Alcohol. 2001;23:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]