Abstract

Heart failure (HF) is hallmarked by an increase in total peripheral resistance (TPR) that compensates for the drop in cardiac output. While initially allowing the maintenance of mean arterial pressure at acceptable levels, the long term up regulation of TPR is prone to compromise cardiac performance and tissue perfusion and to ultimately accelerate disease progression. Augmented vasoconstriction of terminal arteries, the site of TPR regulation, is cooperatively driven by mechanisms like: (i) endothelial dysfunction, (ii) increased sympathetic activity, and (iii) enhanced pressure-induced myogenic responsiveness. Herein we review emerging evidence that the increase in myogenic responsiveness is central to the long-term elevation of TPR in HF. On a molecular level, this augmented intrinsic response is governed by an activation of the tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)/sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) signaling axis in microvascular smooth muscle cells. The beneficial effect of TNFα scavenging strategies on tissue perfusion in HF mouse models adds to the gaining momentum to revisit the use of anti-TNFα treatment modalities in discrete HF patient populations.

Keywords: Heart failure, Resistance arteries, Total peripheral resistance, Myogenic response, Tumor necrosis factor-α, Sphingosine-1-phosphate

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a condition where the heart fails to pump sufficient blood to meet tissue metabolic demands [1]. Clinically, HF progressively damages multiple organ systems and, as a consequence, is a leading cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality affecting over 23 million people worldwide [2]. The socio-economic impact of HF is substantial [2] and prone to grow based on the demographics of the Western population. The disastrous effects of HF and its several co-morbidities on the patients’ quality of life underscores the importance of a complete understanding of this pathology to expedite effective treatments.

The leading symptom in HF is a drop in cardiac output (CO) as a consequence of impaired cardiac contractility. Remarkably, despite severe reductions in CO, concomitant reductions in mean arterial pressure (MAP) are often disproportionately modest. For example, Sullivan and colleagues found that reductions in CO by ~26% were associated with only ~5% decline in MAP [3]. Our group has found a similar disparity between the drop in CO (by ~44%) and the reduction in MAP (by ~8%) when characterizing microvascular changes in a murine model of HF [4]. The mild impact of compromised heart function on MAP results from a compensatory increase in total peripheral resistance (TPR). In early HF, the overall effect of the TPR increase is positive despite the associated negative effects on tissue perfusion and the performance of an already compromised heart. However, the latter become primary elements in the pathogenesis of advanced HF, shedding a spotlight on the mechanisms that regulate TPR under these conditions.

The role of total peripheral resistance in heart failure

Ohm’s law predicts that in order to preserve MAP at near physiological levels, when CO drops TPR must increase. TPR is, indeed, elevated in HF patients [3, 5], albeit at the expense of tissue perfusion (which is inversely proportional to vascular resistance). At early stages of HF, this reduction in tissue perfusion, although counter-intuitive based on its potential to compromise organ viability, is well tolerated on the organ level. At this initial stage, the recruitment of TPR to support maintenance of MAP at pre-set “normal” levels is beneficial to the system. However, with the progression of HF the system drifts towards a situation hallmarked by a maximal increase in TPR and a further declining CO resulting in a falling MAP that is now exclusively governed by CO. Consistent with this notion, a reduction in resting MAP is predictive of future morbidity and mortality and a signature of advanced HF [6–8]. It is also apparent that at late stage HF, where low CO prevails, the negative impact of increased TPR on cardiac performance and tissue perfusion outweighs its beneficial effects on MAP.

In summary, the recruitment of TPR for strict adherence to a predetermined MAP level accelerates the clinical decline in late stage HF and ultimately seals the patient’s fate. Consequently, symptoms resulting from the change in TPR are valuable predictors of the disease’s outcome. In early stage HF, higher TPR is unmasked during exercise (i.e., ~14.3–17.9% higher TPR in the high than in the low risk cohort as calculated from [6] and [9]) and correlates positively with a later severe outcome; as such, the typical symptoms of limited exercise performance [1] assist in diagnosing HF [10].

The HF-induced increase in TPR is achieved through an indiscriminate augmentation in microvascular tone across all vascular beds. This has widespread clinical consequences [11] including: (i) compromised cerebral blood flow [12], possibly explaining the HF-associated decrements in higher order brain function (i.e., memory loss, reduced executive function, psychomotor slowing)[13, 14], (ii) reduced kidney perfusion [15] resulting in decreased serum sodium and increased serum creatinine [16–18], and (iii) inhibited skeletal muscle blood flow [3, 5] leading to altered skeletal muscle structure and function [19]. Importantly, these findings establish impaired organ perfusion as a possible link between HF-associated TPR increases and poor outcome and mortality in HF patients.

The emerging importance of altered TPR in HF is distinct from a purely “cardiocentric” view on this disease. New and exciting avenues of research will lead the way to novel treatment options that will fight this devastating condition by targeting TPR and its anatomical/functional correlates.

From a simplistic perspective, the increase in TPR results from alterations in function and/or structure of pre-capillary resistance arteries, which utilize a plethora of molecular mechanisms to continually match tissue perfusion and metabolic demand. In HF, these molecular mechanisms change driving a functional and structural rearrangement of resistance arteries that soon becomes both hallmarks and promoters of the disease. The current HF literature suggests that the altered activity of pre-capillary resistance arteries (i) results from a combination of decreased vasodilation and increased vasoconstriction and (ii) occurs in the absence of structural remodeling towards a smaller luminal diameter.

Endothelial function in heart failure

Starting in the 1980’s, vascular research has fueled the idea that the endothelial layer precisely governs vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) constriction, and hence TPR using an array of endothelium-derived vasodilating factors (e.g., nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin, and the endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor). In brief, this paradigm suggests that the absence of endothelium-derived substances is responsible for both a reduced capacity to vasodilate (acutely reducing vascular diameter) and disinhibited smooth muscle cell growth (chronically reducing vascular diameter). A strong body of evidence shows that peripheral vasodilation is impaired in HF patients [20–22], that the degree of impairment positively correlates with adverse outcomes [20], and that endothelial function in arteries isolated from HF animal models represents an important target for HF-induced pathological changes [23, 24].

Not surprisingly, compromised vasodilation in HF has been linked to endothelial dysfunction as a result of reduced bioavailability of NO, an observation that fits well with the prominent role assigned to NO in the mechanism of vasorelaxation. Indeed, even prior to the era of NO as an endogenous endothelium-derived factor [25, 26] the NO-donor nitroprusside was successfully used in HF patients to lower TPR and blood pressure, and to improve their cardiac performance [27]. The bioavailability of endogenous NO can be impaired in HF by several pathologic mechanisms: (i) reduced NO production due to reduced expression, activity [28–31] or uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) [32], (ii) increased NO degradation by heightened levels of reactive oxygen species [33], and (iii) decreased sensitivity of VSMC for NO [34–36].

In spite of this evidence, the concept that endothelium-derived NO plays a primary role in the modulation of TPR in HF has been challenged by animal models that show maintained endothelium-dependent dilation despite increased TPR at various stages of HF [4, 37–40]. The temporal dissociation between the increase in TPR and endothelial dysfunction suggests that non-endothelial mechanisms carry the immediate TPR response and that endothelial dysfunction is a delayed complication. From this perspective, the general impairment of endothelial integrity in late stage HF, which is hallmarked by findings like reduced eNOS expression [41], consecutively impaired endothelium-dependent dilation [38, 42], enhanced platelet adhesion [43], expression of pro-inflammatory endothelial markers [44], and reduction of the vascular lumen [45], could be interpreted as “collateral damage” resulting from preceding structural and functional changes. Therefore, it becomes increasingly clear that the concept of endothelial dysfunction does not sufficiently encompass the initial phase of vascular responses to the hemodynamic challenges of HF.

Vascular smooth muscle cell function in heart failure

Recent studies have shed a new light on a possible role for intrinsic VSMC signaling in the cascade of events leading to augmented TPR in HF. VSMCs are the cellular targets of the sympathetic system within the wall of resistance arteries and as such, their sympathetically driven contraction is part of the immediate pressor response that follows the drop in CO. Recent data, however, suggest that the strong sympathetic influence on peripheral arterial tone is only transient; sympathetic tone and vascular reactivity dissociate in later phases of HF. Mice suffering from HF following ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD), start to maintain elevated peripheral tone independent of sympathetic activation at 2 weeks post LAD ligation [4]. In rats 4–6wks post LAD ligation, increased plasma catecholamine levels are compensated by a reduced arterial sensitivity to α2-agonists [46]. Most importantly, human HF patients also display a similar dissociation with elevated skeletal muscle sympathetic nerve activity and corresponding plasma norepinephrine levels [47, 48] on one side and changes in TPR on the other [49].

These data suggest that in early stages of HF, there is a switch of regulatory responsibility away from a central governor (i.e., sympathetic nervous system) towards peripheral local mechanisms. Several vascular mechanisms could, in principle, regulate the local increase in microvascular resistance: (i) microvascular structural remodeling and (ii) the active myogenic response. Inward remodeling (eutrophic or hypertrophic) of resistance arteries, commonly seen in essential hypertension, manages to maintain elevated peripheral resistance with minimal active constriction [50]. However, passive remodeling seems not to play a role in HF: despite elevated intima-media thickness and greater wall-to-lumen ratio in the brachial artery, lumen diameter is no different between control and HF patients [51, 52]. Furthermore, HF does not alter dilation to direct NO donation or wall cross-sectional area of rat [53] and mouse [4] mesenteric arteries, illustrating the absence of structural remodeling. Therefore, instead of undergoing structural changes, resistance arteries seem to adopt a state of “functional remodeling” that allows for a dynamic, but potentially reversible, increase in tone and vascular resistance.

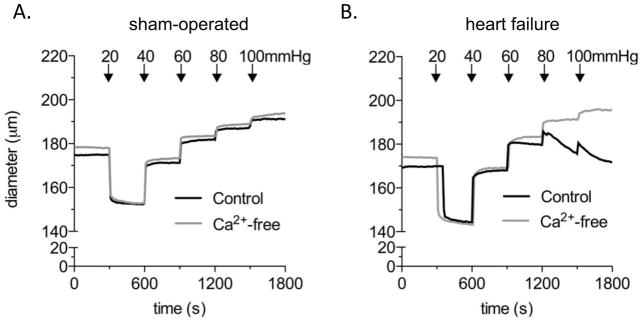

Recent data have identified the enhancement of the pressure-induced myogenic response as the mechanism that promotes a pro-constrictive state in the microvasculature [4, 53, 54] (Figure 1A and B). Although this concept of myogenically driven peripheral vasoconstriction is suited to explain how the sympathetic nervous system could be released from the single purpose of driving TPR (which should benefit homeostasis in the autonomic nervous system), the idea of enhanced myogenic responsiveness in HF present with a conceptual dilemma: the pressure-induced myogenic vasoconstriction increases despite decreasing pressure levels (i.e., systemic MAP). At first glance, this seems counterintuitive and defeats the original purpose of the myogenic response to keep flow constant through proportional adaptation of vascular resistance to pressure. However, the mere existence of a compensatory pattern in HF that sacrifices proper autoregulation for the benefit of stronger vasoconstriction at a given pressure level reveals important insights: (i) maintaining MAP within acceptable limits has priority over tissue perfusion and (ii) compromised tissue perfusion as a hallmark of HF results from a local vascular phenomenon and, at least in early HF stages, occurs independent of changes in MAP.

Figure 1. The myogenic response in heart failure.

(A) In sham-operated mice, posterior cerebral arteries exhibit minimal myogenic tone (i.e. little differences between active pressure-induced vasoconstriction in Ca2+-containing buffer and passive distension in Ca2+-free buffer). All vessels display robust vasoconstriction in response to sympathetic stimulation (i.e. phenylephrine).

(B) At 6–8wks post LAD ligation (i.e., in heart failure), posterior cerebral arteries exhibit strong pressure-induced myogenic vasoconstriction, indicating a heart failure-associated recruitment of these normally “myogenically silent” arteries to the myogenic mechanism [57].

Several molecular concepts explain how enhanced myogenic responsiveness in HF can be maintained over extended periods of time. They propose that in HF, intrinsic signaling mechanisms that regulate myogenic responsiveness under physiological conditions [55, 56] are “hijacked” to increase the “gain” of the response. We propose a new concept that could solve this dilemma by linking the regulation of myogenic responsiveness to the prevalent inflammatory response in HF. In essence, we propose that in HF, the inflammatory cytokine TNFα increases the gain of the myogenic mechanism to enhance myogenic tone at any given level of transmural pressure (Figure 2). This idea of a specific role for TNFα is supported by a combination of complimentary in vivo and in vitro findings: in a LAD-ligation mouse model, (i) HF is associated with an upregulation of TNFα mRNA and protein within the VSMCs of the microvascular wall [57], (ii) in vitro TNFα scavenging with etanercept [58] normalizes augmented myogenic responsiveness in isolated cerebral and skeletal muscle resistance arteries [57, 59], (iii) in vivo (systemic) etanercept treatment restores cerebral blood flow [57], and (iv) arteries isolated from HF TNFα−/− mice do not display enhanced myogenic responsiveness [54, 59].

Figure 2. The TNFα/S1P signaling axis in heart failure.

On the level of resistance arteries, heart failure (HF) is associated with increased autocrine and paracrine effects of microvascular smooth muscle-derived TNFα. The functional changes observed in resistance arteries of HF mice result from two distinct TNFα-driven mechanisms: (i) activation of sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1)-mediated sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) synthesis and (ii) inhibition of S1P degradation (primarily resulting from reduced cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) expression). These effects combine to increase S1P bioavailability and hence, S1P-driven pressure-induced myogenic vasoconstriction.

TNFα targets microvascular sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) signaling, which provides an immediate link to the regulation of myogenic responsiveness. As a bioactive phospholipid, S1P is formed by VSMC in response to altered transmural pressure and is required for the initiation and maintenance of the pressure-induced myogenic response [60–63] (for a comprehensive review see [55]). Briefly, increases in transmural pressure promote the synthesis of S1P through phosphorylation of sphingosine (a sphingolipid component of the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane) by sphingosine kinase 1 (Sphk1). The activation of Sphk1 results from a pressure-dependent and Erk1/2-mediated phosphorylation of Sphk1 at Ser255, which promotes the translocation of Sphk1 to the sphingosine-rich plasma membrane. Pressure-dependently formed S1P serves two functions in smooth muscle cells: i) intracellular S1P stimulates the release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum to enhance MLCK activation and MLC20 phosphorylation and ii) the extracellular portion of S1P is a ligand to S1P2 G-protein coupled receptors (S1P2R) and promotes Ca2+-sensitization through RhoA/Rho kinase activation, subsequent MLCP inactivation and the resulting reduction of MLC20 dephosphorylation. The bioavailability of S1P is determined by its production by Sphk1 and its degradation by the S1P phosphohydrolase 1 (SPP1, localized on the endoplasmic reticulum). The import of S1P prior to its intracellular degradation is functionally linked to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR), which identifies CFTR as a critical bottleneck for S1P degradation by SPP1 [54, 62]. TNFα regulates the intramural concentration of S1P through two complementary mechanisms: SphK1 activation [57, 64, 65] and CFTR downregulation [62, 66].

The downregulation of CFTR seems to represent the primary mechanism by which TNFα enhances myogenic responsiveness and hence, TPR in vivo. The expression of CFTR in VSMCs is inversely proportional to (i) the size of the infarct and (ii) the amplitude of the pressure-induced myogenic response. Systemic treatment of HF mice with etanercept 6 weeks post-MI (i.e., when pathologic cardiac remodeling was complete) restores microvascular CFTR expression and normalizes myogenic responsiveness and cerebral blood flow [54]. The outcome showing the rescue of CFTR expression and normalization of myogenic responsiveness and cerebral blood flow by late onset etanercept treatment has several important implications: (i) TNFα is central to the microvascular changes in HF, (ii) microvascular effects of TNFα are therapeutically accessible, and (iii) the HF-induced microvascular phenotype is reversible. Along the same lines, it is tempting to speculate that the reversal of microvascular functional remodeling might delay the progression of cardiac damage through reduction of the cardiac mechanical load. Separate results from HF mice treated immediately following LAD ligation demonstrate both a normalization of microvascular function and a clear trend towards better cardiac performance. This could either result from a direct effect of etanercept on the TNFα-dependent progression of cardiac damage or the reduction in TPR, which would reduce the strain on the heart, or a combination of both.

The translational perspective

The concept reviewed here promotes the idea of using anti-TNFα treatment (i.e., etanercept, infliximab) to ameliorate the microvascular effects of HF. The intended therapeutic consequence of improved tissue perfusion has the potential to recover end organ function and some of the clinical deficits. The underlying idea of our therapeutic approach is similar to strategies that employ any combination of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor antagonists, hydralazine, and nitrates to enhance vasodilation and hence, tissue perfusion [11, 67, 68]. The primary advantage of our therapeutic approach lies in its specificity; it directly translates the mechanistic knowledge on TNFα-driven myogenic S1P signaling and its effect on tissue perfusion in HF to specifically target this response and to modulate its strength at full preservation of autoregulatory function. Of note, the full elucidation of the TNFα/S1P signalling pathway provides the opportunity to test and exploit several drug classes that target its different signaling components (e.g. TNFα by etanercept/infliximab, S1P2R by JTE-013 and Sphk1 by dimethylsphingosine).

With regard to TNFα, clinical trials (i.e., RECOVER, RENAISSANCE, and RENEWAL, all multi-centre, double-blind and placebo-controlled) [69] with anti-TNFα treatments in HF patients have unfortunately shown no benefit, a result that might have been favored by the rather cardiocentric study layout. The latter view largely neglected vascular parameters like blood flow, MAP, or TPR as putatively important endpoints.

New insights from our animal experiments allow for alternative interpretations: although speculative at this point, those data provide an incentive to revisit anti-TNFα treatment as a viable treatment option for some HF-associated co-morbidities. For example, the beneficial effect of etanercept on cerebral blood flow in mice with HF could, if translatable, be suited to alleviate the impact of HF on neurological function in human patients. This argument could possibly be expanded to other organs as well (i.e., kidney, skeletal muscle), which could benefit from reversing the tissue perfusion-limiting effects of TNFα in the microcirculation. In this regard, it is even more regrettable that the endpoints targeted in the human TNFα scavenger studies did not provide more insight into the effects of the treatment on end organ function. It is also worth a consideration that the anti-TNFα treatment protocols in all previous trials were not intended, leave alone optimized, to correct the microvascular dysfunction. Future approaches with the appropriate “microvascular endpoint” might be able to correct this shortcoming.

In some of the human trials, TNFα scavengers tended to increase risk of death and hospitalization, which resulted in premature termination of the studies. Although the underlying mechanisms remain elusive to date, our microvascular data might advise new ways to interpret these outcomes: A primary problem likely originates from the composition of the patient population, which did not discriminate patients based on the parameter of HF severity (i.e., studies included patients from NYHA stage II to stage IV). This was perfectly reasonable based on the trials’ primary assumption that TNFα scavengers would improve cardiac function independent of the stage of HF. However, the new vascular data invite the speculation that TNFα scavenging at late HF stages drastically reduces TPR, thereby removing the last line of defense to maintain MAP in the setting of a maximally weakened heart. A severe reduction in MAP or even death would be the logical endpoints of such a scenario.

Conclusions

In essence, accumulating evidence suggests that the compensatory TPR increase in HF results from a TNFα-driven enhancement of myogenic responsiveness in resistance arteries. Although critically important to the maintenance of MAP, it has increasingly negative effects on tissue perfusion and cardiac performance with further disease progression.

Following this line of arguments, it is even tempting to speculate that in a scenario where CO is only moderately reduced and MAP still at acceptable levels (i.e., low-grade HF), TNFα-driven and pressure-independent increases in TPR represent more of a complicating factor (that puts additional strain on the heart and hence, negatively impacts long-term prognosis) rather than a hemodynamic necessity.

Data from animal studies demonstrate that the TNFα-driven increase in TPR can be successfully targeted with a TNFα scavenging strategy, raising both the opportunity and challenge to translate these findings into the human situation. The major challenge lies in the negative outcomes of previous clinical trials that have severely dampened the enthusiasm for the use of TNFα scavengers in the context of HF. However, re-focusing on vascular endpoints and carefully re-building the argument from a strictly microvascular perspective might help to resurrect a treatment option with potentially high benefits for HF patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Peter Backx, Dr. Darcy Lidington and Crystal Aultman for their careful reading of the manuscript. This study was supported by: Ontario Graduate Scholarship – Science and Technology (J.T.K.), Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario – Queen Elizabeth II Scholarship (J.T.K.), operating and infrastructure grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (S.-S.B., MOP-84402), Canadian Foundation for Innovation and Ontario Research Fund (S.-S.B., 11810), the Canadian Stroke Network (S.-S.B.); Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario New Investigator Award (S.-S.B.) and start-up funding from the University of Toronto (S.-S.B.).

References

- 1.Guyton AC. HJE: Textbook of medical physiology. Toronto: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000. pp. 235–241. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bui AL, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and risk profile of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 8:30–41. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan MJ, Knight JD, Higginbotham MB, Cobb FR. Relation between central and peripheral hemodynamics during exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. Muscle blood flow is reduced with maintenance of arterial perfusion pressure. Circulation. 1989;80:769–781. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.4.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoefer J, Azam MA, Kroetsch JT, Leong-Poi H, Momen MA, Voigtlaender-Bolz J, Scherer EQ, Meissner A, Bolz SS, Husain M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate-dependent activation of p38 mapk maintains elevated peripheral resistance in heart failure through increased myogenic vasoconstriction. Circ Res. 107:923–933. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindsay DC, Holdright DR, Clarke D, Anand IS, Poole-Wilson PA, Collins P. Endothelial control of lower limb blood flow in chronic heart failure. Heart. 1996;75:469–476. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.5.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenblum H, Helmke S, Williams P, Teruya S, Jones M, Burkhoff D, Mancini D, Maurer MS. Peak cardiac power measured noninvasively with a bioreactance technique is a predictor of adverse outcomes in patients with advanced heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 16:254–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin MH, Goldman L. Correlates of early hospital readmission or death in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:1640–1644. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowie MR, Wood DA, Coats AJ, Thompson SG, Suresh V, Poole-Wilson PA, Sutton GC. Survival of patients with a new diagnosis of heart failure: A population based study. Heart. 2000;83:505–510. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.5.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams SG, Jackson M, Cooke GA, Barker D, Patwala A, Wright DJ, Albuoaini K, Tan LB. How do different indicators of cardiac pump function impact upon the long-term prognosis of patients with chronic heart failure? Am Heart J. 2005;150:983. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu P, Arnold M, Belenkie I, Howlett J, Huckell V, Ignazewski A, LeBlanc MH, McKelvie R, Niznick J, Parker JD, Rao V, Ross H, Roy D, Smith S, Sussex B, Teo K, Tsuyuki R, White M, Beanlands D, Bernstein V, Davies R, Issac D, Johnstone D, Lee H, Moe G, Newton G, Pflugfelder P, Roth S, Rouleau J, Yusuf S. The 2001 canadian cardiovascular society consensus guideline update for the management and prevention of heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2001;17 (Suppl E):5E–25E. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schrier RW, Abraham WT. Hormones and hemodynamics in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:577–585. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi BR, Kim JS, Yang YJ, Park KM, Lee CW, Kim YH, Hong MK, Song JK, Park SW, Park SJ, Kim JJ. Factors associated with decreased cerebral blood flow in congestive heart failure secondary to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1365–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pressler SJ, Kim J, Riley P, Ronis DL, Gradus-Pizlo I. Memory dysfunction, psychomotor slowing, and decreased executive function predict mortality in patients with heart failure and low ejection fraction. J Card Fail. 16:750–760. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauve MJ, Lewis WR, Blankenbiller M, Rickabaugh B, Pressler SJ. Cognitive impairments in chronic heart failure: A case controlled study. J Card Fail. 2009;15:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang WH, Mullens W. Cardiorenal syndrome in decompensated heart failure. Heart. 96:255–260. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.166256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein L, O’Connor CM, Leimberger JD, Gattis-Stough W, Pina IL, Felker GM, Adams KF, Jr, Califf RM, Gheorghiade M. Lower serum sodium is associated with increased short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with worsening heart failure: Results from the outcomes of a prospective trial of intravenous milrinone for exacerbations of chronic heart failure (optime-chf) study. Circulation. 2005;111:2454–2460. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165065.82609.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kearney MT, Fox KA, Lee AJ, Prescott RJ, Shah AM, Batin PD, Baig W, Lindsay S, Callahan TS, Shell WE, Eckberg DL, Zaman AG, Williams S, Neilson JM, Nolan J. Predicting death due to progressive heart failure in patients with mild-to-moderate chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1801–1808. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blair JE, Pang PS, Schrier RW, Metra M, Traver B, Cook T, Campia U, Ambrosy A, Burnett JC, Jr, Grinfeld L, Maggioni AP, Swedberg K, Udelson JE, Zannad F, Konstam MA, Gheorghiade M. Changes in renal function during hospitalization and soon after discharge in patients admitted for worsening heart failure in the placebo group of the everest trial. Eur Heart J. 32:2563–2572. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poole DC, Hirai DM, Copp SW, Musch TI. Muscle oxygen transport and utilization in heart failure: Implications for exercise (in)tolerance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 302:H1050–1063. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00943.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz SD, Hryniewicz K, Hriljac I, Balidemaj K, Dimayuga C, Hudaihed A, Yasskiy A. Vascular endothelial dysfunction and mortality risk in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:310–314. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153349.77489.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hillier C, Cowburn PJ, Morton JJ, Dargie HJ, Cleland JG, McMurray JJ, McGrath JC. Structural and functional assessment of small arteries in patients with chronic heart failure. Clin Sci (Lond) 1999;97:671–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz SD, Krum H. Acetylcholine-mediated vasodilation in the forearm circulation of patients with heart failure: Indirect evidence for the role of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:1089–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01466-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malmsjo M, Bergdahl A, Zhao XH, Sun XY, Hedner T, Edvinsson L, Erlinge D. Enhanced acetylcholine and p2y-receptor stimulated vascular edhf-dilatation in congestive heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:200–209. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ontkean M, Gay R, Greenberg B. Diminished endothelium-derived relaxing factor activity in an experimental model of chronic heart failure. Circ Res. 1991;69:1088–1096. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.4.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980;288:373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer RM, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller RR, Vismara LA, Zelis R, Amsterdam EA, Mason DT. Clinical use of sodium nitroprusside in chronic ischemic heart disease. Effects on peripheral vascular resistance and venous tone and on ventricular volume, pump and mechanical performance. Circulation. 1975;51:328–336. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.51.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comini L, Bachetti T, Gaia G, Pasini E, Agnoletti L, Pepi P, Ceconi C, Curello S, Ferrari R. Aorta and skeletal muscle no synthase expression in experimental heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:2241–2248. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones SP, Greer JJ, van Haperen R, Duncker DJ, de Crom R, Lefer DJ. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase overexpression attenuates congestive heart failure in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4891–4896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0837428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith CJ, Sun D, Hoegler C, Roth BS, Zhang X, Zhao G, Xu XB, Kobari Y, Pritchard K, Jr, Sessa WC, Hintze TH. Reduced gene expression of vascular endothelial no synthase and cyclooxygenase-1 in heart failure. Circ Res. 1996;78:58–64. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scherrer-Crosbie M, Ullrich R, Bloch KD, Nakajima H, Nasseri B, Aretz HT, Lindsey ML, Vancon AC, Huang PL, Lee RT, Zapol WM, Picard MH. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase limits left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation. 2001;104:1286–1291. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.094298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Setoguchi S, Hirooka Y, Eshima K, Shimokawa H, Takeshita A. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves impaired endothelium-dependent forearm vasodilation in patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2002;39:363–368. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Widder J, Behr T, Fraccarollo D, Hu K, Galuppo P, Tas P, Angermann CE, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. Vascular endothelial dysfunction and superoxide anion production in heart failure are p38 map kinase-dependent. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karim SM, Rhee AY, Given AM, Faulx MD, Hoit BD, Brozovich FV. Vascular reactivity in heart failure: Role of myosin light chain phosphatase. Circ Res. 2004;95:612–618. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000142736.39359.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan DR, Dixon LJ, Hanratty CG, Hughes SM, Leahey WJ, Rooney KP, Johnston GD, McVeigh GE. Impaired endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation in elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6:901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Negrao CE, Hamilton MA, Fonarow GC, Hage A, Moriguchi JD, Middlekauff HR. Impaired endothelium-mediated vasodilation is not the principal cause of vasoconstriction in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H168–174. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.1.H168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Main JS, Forster C, Armstrong PW. Inhibitory role of the coronary arterial endothelium to alpha-adrenergic stimulation in experimental heart failure. Circ Res. 1991;68:940–946. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.4.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun D, Huang A, Zhao G, Bernstein R, Forfia P, Xu X, Koller A, Kaley G, Hintze TH. Reduced no-dependent arteriolar dilation during the development of cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H461–468. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.2.H461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ueda A, Ohyanagi M, Koida S, Iwasaki T. Enhanced release of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in small coronary arteries from rats with congestive heart failure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:615–621. doi: 10.1111/j.0305-1870.2005.04240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Murchu B, Miller VM, Perrella MA, Burnett JC., Jr Increased production of nitric oxide in coronary arteries during congestive heart failure. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:165–171. doi: 10.1172/JCI116940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gill RM, Braz JC, Jin N, Etgen GJ, Shen W. Restoration of impaired endothelium-dependent coronary vasodilation in failing heart: Role of enos phosphorylation and cgmp/cgk-i signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2782–2790. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00831.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang P, Hou M, Li Y, Xu X, Barsoum M, Chen Y, Bache RJ. Nadph oxidase contributes to coronary endothelial dysfunction in the failing heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H840–846. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00519.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Peuter OR, Kok WE, Torp-Pedersen C, Buller HR, Kamphuisen PW. Systolic heart failure: A prothrombotic state. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35:497–504. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1234145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yanavitski M, Givertz MM. Novel biomarkers in acute heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 8:206–211. doi: 10.1007/s11897-011-0065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Mast Q, Beutler JJ. The prevalence of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis in risk groups: A systematic literature review. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1333–1340. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328329bbf4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng QP, Bergdahl A, Lu XR, Sun XY, Edvinsson L, Hedner T. Vascular alpha-2 adrenoceptor function is decreased in rats with congestive heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;31:577–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Notarius CF, Morris BL, Floras JS. Dissociation between reflex sympathetic and forearm vascular responses to lower body negative pressure in heart failure patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1760–1766. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00012.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Witte KK, Notarius CF, Ivanov J, Floras JS. Muscle sympathetic nerve activity and ventilation during exercise in subjects with and without chronic heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24:275–278. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70176-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leimbach WN, Jr, Wallin BG, Victor RG, Aylward PE, Sundlof G, Mark AL. Direct evidence from intraneural recordings for increased central sympathetic outflow in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1986;73:913–919. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.5.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mulvany MJ. Small artery remodeling and significance in the development of hypertension. News Physiol Sci. 2002;17:105–109. doi: 10.1152/nips.01366.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poelzl G, Frick M, Huegel H, Lackner B, Alber HF, Mair J, Herold M, Schwarzacher S, Pachinger O, Weidinger F. Chronic heart failure is associated with vascular remodeling of the brachial artery. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakamura M, Sugawara S, Arakawa N, Nagano M, Shizuka T, Shimoda Y, Sakai T, Hiramori K. Reduced vascular compliance is associated with impaired endothelium-dependent dilatation in the brachial artery of patients with congestive heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004;10:36–42. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(03)00585-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gschwend S, Henning RH, Pinto YM, de Zeeuw D, van Gilst WH, Buikema H. Myogenic constriction is increased in mesenteric resistance arteries from rats with chronic heart failure: Instantaneous counteraction by acute at1 receptor blockade. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:1317–1325. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meissner A, Yang J, Kroetsch JT, Sauve M, Dax H, Momen A, Noyan-Ashraf MH, Heximer S, Husain M, Lidington D, Bolz SS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated downregulation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator drives pathological sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling in a mouse model of heart failure. Circulation. 125:2739–2750. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schubert R, Lidington D, Bolz SS. The emerging role of ca2+ sensitivity regulation in promoting myogenic vasoconstriction. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hill MA, Davis MJ, Meininger GA, Potocnik SJ, Murphy TV. Arteriolar myogenic signalling mechanisms: Implications for local vascular function. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2006;34:67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang J, Noyan-Ashraf MH, Meissner A, Voigtlaender-Bolz J, Kroetsch JT, Foltz W, Jaffray D, Kapoor A, Momen A, Heximer SP, Zhang H, van Eede M, Henkelman RM, Matthews SG, Lidington D, Husain M, Bolz SS. Proximal cerebral arteries develop myogenic responsiveness in heart failure via tumor necrosis factor-alpha-dependent activation of sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling. Circulation. 126:196–206. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohler KM, Sleath PR, Fitzner JN, Cerretti DP, Alderson M, Kerwar SS, Torrance DS, Otten-Evans C, Greenstreet T, Weerawarna K, et al. Protection against a lethal dose of endotoxin by an inhibitor of tumour necrosis factor processing. Nature. 1994;370:218–220. doi: 10.1038/370218a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kroetsch JTMA, Momen MA, Husain M, Bolz SS. Tnf is central to the augmented myogenic response of skeletal muscle resistance arteries in heart failure. FASEB J. 2011;25 (S):1026. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bolz SS, Vogel L, Sollinger D, Derwand R, Boer C, Pitson SM, Spiegel S, Pohl U. Sphingosine kinase modulates microvascular tone and myogenic responses through activation of rhoa/rho kinase. Circulation. 2003;108:342–347. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080324.12530.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keller M, Lidington D, Vogel L, Peter BF, Sohn HY, Pagano PJ, Pitson S, Spiegel S, Pohl U, Bolz SS. Sphingosine kinase functionally links elevated transmural pressure and increased reactive oxygen species formation in resistance arteries. FASEB J. 2006;20:702–704. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4075fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peter BF, Lidington D, Harada A, Bolz HJ, Vogel L, Heximer S, Spiegel S, Pohl U, Bolz SS. Role of sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphohydrolase 1 in the regulation of resistance artery tone. Circ Res. 2008;103:315–324. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lidington D, Peter BF, Meissner A, Kroetsch JT, Pitson SM, Pohl U, Bolz SS. The phosphorylation motif at serine 225 governs the localization and function of sphingosine kinase 1 in resistance arteries. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1916–1922. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.194803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pitson SM, Moretti PA, Zebol JR, Xia P, Gamble JR, Vadas MA, D’Andrea RJ, Wattenberg BW. Expression of a catalytically inactive sphingosine kinase mutant blocks agonist-induced sphingosine kinase activation. A dominant-negative sphingosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33945–33950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pitson SM, Moretti PA, Zebol JR, Lynn HE, Xia P, Vadas MA, Wattenberg BW. Activation of sphingosine kinase 1 by erk1/2-mediated phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2003;22:5491–5500. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boujaoude LC, Bradshaw-Wilder C, Mao C, Cohn J, Ogretmen B, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator regulates uptake of sphingoid base phosphates and lysophosphatidic acid: Modulation of cellular activity of sphingosine 1-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35258–35264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cole RT, Kalogeropoulos AP, Georgiopoulou VV, Gheorghiade M, Quyyumi A, Yancy C, Butler J. Hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate in heart failure: Historical perspective, mechanisms, and future directions. Circulation. 123:2414–2422. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.012781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Caccamo MA, Eckman PM. Pharmacologic therapy for new york heart association class iv heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 17:213–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2011.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mann DL. Targeted anticytokine therapy and the failing heart. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:9C–16C. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.03.007. discussion 38C–40C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]