Abstract

Objectives: Accumulating evidence suggests that gender affects the incidence and severity of several pulmonary diseases. Previous studies on mice have shown gender differences in susceptibility to naphthalene‐induced lung injury, where Clara cell damage was found to occur earlier and to be more extensive in females than in males. However, very little is known about whether there are any gender differences in subsequent lung repair responses. The aim of this study was to investigate whether gender plays an important role in pulmonary regenerative response to naphthalene‐induced Clara cell ablation.

Materials and methods: Adult male and female mice were injected with a low, medium, or high dose of naphthalene, and lung tissue regeneration was examined by immunohistochemical staining for cell proliferation marker (Ki‐67) and mitosis marker (phosphohistone‐3).

Results: Histopathological analysis showed that naphthalene‐induced Clara cell necrosis was more prominent in the lungs of female mice as compared to male mice. Cell proliferation and mitosis in both the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium and peribronchiolar interstitium of female mice was significantly greater than that of male mice after treatment with the low and medium doses. However, after treatment with high dose of naphthalene, lung regeneration was delayed in female mice, while male mice mounted a timely regenerative response.

Conclusions: These findings show that there are clear gender differences in naphthalene‐induced lung injury and repair.

Introduction

Substantial epidemiological evidence suggests that gender affects the incidence and severity of several lung diseases (1). Although incidence of lung cancer and mortality rate as a result of it, have appeared to reach a plateau in men, it continues to rise in women (1). Among lifetime non‐smokers, worldwide, lung cancer is much more common in women than in men (2), and odds ratios for different histological types of lung cancer are consistently higher for women than for men with equivalent tobacco exposure (3). In addition, adenocarcinoma of the lung is more common in women than in men regardless of smoking status (2, 4, 5, 6, 7). Interestingly, DNA repair capacity has been shown to be 10–15% lower in female lung cancer patients than in their male counterparts (8), and a previous study has found a higher frequency of a specific mutation (G to T transversion) in the p53 gene in lung tumours of women, than in those of men (9). Among the general population, there is also a greater prevalence of asthma in women than in men during the time of puberty to the 5th/6th decade of life (1). Furthermore, lung function of females with cystic fibrosis (CF) deteriorates 26% more rapidly than that of their male counterparts (10), and female CF patients have a worse prognosis than do male CF patients, as women with CF, on average, die at a significantly lower age (28 years vs. 37 years) in Canada (11, 12). In addition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects more non‐smoking females than non‐smoking males (7, 13). Although a reliable animal model for studying pathogenesis of COPD has not yet been well established, female mice exposed to cigarette smoke have been shown to develop emphysematous‐like changes in alveolar structure more rapidly than male mice (14). Gender differences also appear to exist in a rodent model of pulmonary fibrosis, as a previous study has demonstrated that female rats have higher mortality rates and more severe fibrosis in the lungs than male rats in response to bleomycin treatment (15). However, ovariectomized female rats displayed less pulmonary fibrosis than did sham‐operated controls, and hormone replacement therapy with estradiol restored the fibrotic response, suggesting that the exaggerated response of female rats to lung injury may be mediated by sex hormones (15). Studies have also shown that oestrogen can regulate alveolar formation, loss, and regeneration in the lungs of female mice (16, 17).

Many respiratory disorders, such as asthma and CF, involve airway inflammation and epithelial cell injury. Subsequent regeneration and repair of lung epithelium is a vital process to help maintain function and integrity of the airways. Clara cells are non‐mucus and non‐ciliated secretory epithelial cells located in both the proximal and distal airways of mice (18). Many laboratories have used naphthalene treatment of experimental animals, which causes Clara cell‐specific injury, as a model to study the molecular and cellular mechanisms of airway epithelial cell regeneration (19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24). Naphthalene is one of the most common polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons found in cigarette smoke, automobile emissions, pesticides, and ambient air. Metabolism of naphthalene to its cytotoxic and reactive intermediate, 1R, 2S‐naphthalene oxide, is mediated by the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 2F2, which is abundantly expressed in Clara cells; thus, this makes this cell type the primary target for injury in the airways of mice (25, 26, 27, 28). After treatment with naphthalene, injured and necrotic Clara cells are replaced by other airway epithelial cells, which undergo dynamic changes in cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation (18). Many different cell types have been shown to partake in the pulmonary regenerative response to naphthalene‐induced depletion of Clara cells in mice, and those identified to date include basal cells (29, 30), pulmonary neuroendocrine cells (PNEC) (23, 31, 32), bronchoalveolar stem cells (BASC) (21, 33), ciliated cells (22, 24, 34), peribronchiolar interstitial cells (20, 35), and a pollutant‐resistant subpopulation of Clara cells that retain their expression of Clara cell 10‐kDa secretory protein (CC10/CCSP), also known as variant CC10/CCSP‐expressing (vCE) cells (36, 37).

Since female sex hormones, such as oestrogen, can induce expression of many drug‐metabolizing isoenzymes in the lungs, females can undergo more site‐specific metabolic bioactivation of xenobiotics to toxic metabolites than males (2, 5, 7, 13). This may very well be the case for naphthalene, as a previous study has shown that hormonal patterns associated with different stages of the oestrous cycle can alter naphthalene metabolism in the lungs of cycling virgin female mice (38). Furthermore, another study demonstrated that female mice have a more rapid metabolism of naphthalene associated with earlier onset and greater extent of Clara cell injury as compared to male mice administered the same dose of naphthalene (39). However, the aforementioned study only examined gender differences in acute lung injury response following naphthalene exposure, and very little is known about the effect of gender on long‐term cellular repair responses. Our goal in this study was to determine whether there is a gender‐based difference in the pulmonary regenerative response, which occurs subsequent to naphthalene‐induced Clara cell ablation, in mice. Defining gender differences in lung injury and repair is important in understanding the basis for gender differences in susceptibility to various pulmonary diseases.

Materials and methods

Animals and treatments

Adult (2–4 months old) male and female C57BL/6 mice were used in these experiments. All animals were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constant, QC, Canada) and were maintained in accordance to the guidelines of the Hospital for Sick Children, animal facilities. All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Hospital for Sick Children institutional committee for humane use of laboratory animals. Mice were housed five per cage, and were maintained in an environment with controlled temperature and humidity and a 12‐h dark/light cycle. All were fed standard mouse chow and water ad libitum. In order to elicit a sufficient range of repair responses in the lungs of male and female mice, dose–response studies were performed by administering three different doses of naphthalene designated as follows: low dose (50 mg/kg body weight), medium dose (100 mg/kg body weight), and high dose (200 mg/kg body weight). Naphthalene (> 99% pure) was dissolved in corn oil (both from Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) and administered such that the specified doses resulted as 10 ml/kg body weight. Naphthalene or corn oil alone (10 ml/kg body weight, vehicle control) was administered via a single intraperitoneal injection. Groups of three to seven mice per gender were killed at different time points (0, 2, 14, and 21 days) after treatment with each dose of naphthalene or 2 days after corn oil treatment (control group). All mice were dosed and killed between 08:00 h and 10:00 h, to minimize influence of diurnal glutathione abundance fluctuations on extent of naphthalene injury.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Immediately after death, mouse lung tissue was collected for routine histology and immunohistochemistry, and was fixed overnight in 10% buffered formalin followed by paraffin embedding. Five‐micrometre lung sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological examination of naphthalene‐induced tissue changes, using a light microscope. Serial sections of mouse lung tissue were also used for immunohistochemical staining for the following: (i) Clara cell marker: Clara cell 10‐kDa secretory protein (CC10/CCSP); (ii) ciliated cell marker: FoxJ1; (iii) cell proliferation marker: Ki‐67; and (iv) mitosis marker: phosphohistone‐3 (PH‐3). Briefly, sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and then microwaved in 0.01 m citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 18.5 min at 1000 watts for antigen unmasking. Sections were kept in the hot citrate buffer solution for an additional 20 min, washed in water, treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 min, and then transferred to phosphate‐buffered saline (pH 7.2). Tissue sections were blocked with 10% normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with one of the following primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti‐mouse CC10/CCSP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 1 : 7000 dilution; mouse monoclonal anti‐human FoxJ1 (Seven Hills Bioreagents, Cincinnati, OH, USA) at 1 : 6000 dilution; rabbit monoclonal anti‐human Ki‐67 (Lab Vision Corporation, Fremont, CA, USA) at 1 : 200 dilution; or rabbit polyclonal anti‐human PH‐3 (Upstate Laboratories, Temecula, CA, USA) at 1 : 6000 dilution. All primary antibodies were incubated overnight on tissue sections at 4 °C, and immunohistochemical staining was carried out using the immunoperoxidase method according to guidelines for the Vectastain Elite ABC Peroxidase Kit for rabbit primary antibodies and M.O.M. Immunodetection Peroxidase Kit for the mouse primary antibody (both from Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). Sites of peroxidase binding were detected using chromogenic 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride substrate, and positive staining appeared brown in colour. Tissue sections were counterstained with haematoxylin, and sections stained without primary antibody served as negative controls.

Histopathological analysis

H&E‐stained mouse lung sections from each group were scored for extent of naphthalene‐induced bronchiolar epithelial cell necrosis using a light microscope at ×400 magnification. Degree of necrosis was estimated semi‐quantitatively, and was expressed for each mouse as the mean of 10 random fields within each section (one section per mouse) classified on a scale of 0–3. Scoring criteria were as follows: 0, no necrosis, defined as no detection of necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells exfoliated within the airway lumen; 1, mild, defined as only occasional detection of necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells exfoliated within the airway lumen; 2, moderate, more frequent detection of necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells exfoliated in the airway lumen; 3, severe, very frequent detection of numerous necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells in the airway lumen. Data are presented as mean necrosis score ± standard error of three to seven mice per gender at each time point after treatment with each of the three doses of naphthalene.

Labelling index

Labelling index (LI) was first determined using the cell proliferation marker (Ki‐67) and was expressed as percentage of Ki‐67‐positive nuclei in distal bronchiolar airway epithelium and in the peribronchiolar interstitium. Distal bronchiolar airways were defined as distal conducting airways with a diameter of 200 µm or less and distal bronchiolar airway epithelium was defined as cells located between the basal lamina and airway lumen, and peribronchiolar interstitium was defined as cells located between the basal lamina of the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium and an adjacent blood vessel, alveolus, or bronchiole. Number of Ki‐67‐positive nuclei and total number of nuclei in the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium and in the peribronchiolar interstitium were counted separately in five random microscopic fields per section, using a light microscope at ×400 magnification. LI was calculated by dividing the number of Ki‐67‐positive nuclei by total number of nuclei per section (one section per mouse). Data are presented as means ± standard errors of three to seven mice per gender at each time point after treatment with each of the three doses of naphthalene. In order to confirm gender differences in lung regeneration initially observed with the Ki‐67 LI data, mitotic index (MI) was also determined exactly as described for the LI; however, instead of Ki‐67, the mitosis marker, PH‐3, was detected.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons between groups at different time points were performed by one‐way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc tests (Prism 4.0). Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Histopathological analysis

Naphthalene‐induced histopathological changes in the lungs of male and female mice were assessed after H&E staining. At 0 day of naphthalene treatment (control group), no histopathological changes were detected, and normal bronchiolar epithelium, consisting mainly of columnar non‐ciliated (Clara) cells and to a lesser extent, ciliated cells, was observed in the lungs of both male (Fig. 1a,i,q) and female (Fig. 1e,m,u) mice as expected. Similarly, normal bronchiolar epithelium with no histopathological changes was also observed in both male and female mice upon treatment with corn oil only (data not shown). Exfoliation of numerous injured and necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells into the airway lumen was the prominent histopathological change observed in other categories, and was detected in female mice 2 days after injection with the low, medium, or high dose of naphthalene (Fig. 1f,n,v), while in male mice, it was observed only after injection with the medium or high dose (Fig. 1j,r). This sloughing of necrotic cells from bronchiolar epithelium left the basement membrane denuded, with only few uninjured and flattened bronchiolar epithelial cells remaining intact, in both male and female mice, upon treatment with high dose of naphthalene (Fig. 1r,v). Extent of bronchiolar epithelial cell injury and ablation was also dose‐dependent, with the most drastic changes observed at 2 days after treatment with high dose in both male and female mice (Fig. 1r,v). Moreover, bronchiolar injury was more prominent in the lungs of female mice (Fig. 1f,n,v) as compared to male mice (Fig. 1b,j,r) after injection with any (low, medium, or high) of the naphthalene doses. In addition, extent of bronchiolar epithelial cell necrosis was much greater in the lungs of female mice as compared to male mice at 2 days after treatment with each dose of naphthalene, and was confirmed by semi‐quantitation (Table 1). Mean necrosis score of the bronchiolar epithelium in both male and female mice peaked at 2 days and returned to baseline levels by 14–21 days after treatment with each dose of naphthalene (Table 1). Within 14–21 days after injection with low, medium, or high dose, the bronchiolar epithelium appeared fully regenerated and restored with abundance of columnar non‐ciliated (Clara) cells in both male (Fig. 1c,d,k,l,s,t) and female (Fig. 1g,h,o,p,x) mice. However, few residual injured and exfoliated bronchiolar epithelial cells were detected at 14 days after injection with high dose of naphthalene in female mice (Fig. 1w) but not in male mice (Fig. 1s); thus, it has shown faster recovery from lung epithelial cell injury in male mice. Mean necrosis score was also significantly greater in bronchiolar epithelium of female mice as compared to male mice at 14 days after injection with high dose of naphthalene (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Haematoxylin and eosin analysis of bronchiolar epithelial (Clara) cell injury and renewal in male and female mice after treatment with naphthalene. Lung histopathology was examined at 0, 2, 14, and 21 days after injection with (a–h) low dose (50 mg/kg), (i–p) medium dose (100 mg/kg), or (q–x) high dose (200 mg/kg) of naphthalene. A healthy and normal bronchiolar epithelium was detected in both male (a, i, and q) and female (e, m, and u) mice at 0 days (control). Injured and necrotic Clara cells, which have exfoliated into the bronchiolar lumen, were detected in male mice at 2 days after injection with either medium or high dose of naphthalene (asterisks in (j) and (r), respectively), and in female mice at 2 days after injection with low, medium, or high doses of naphthalene (asterisks in (f), (n), and (v), respectively). See Table 1 for necrosis scoring. Few residual injured and exfoliated bronchiolar epithelial cells were detected at 14 days after injection with high dose of naphthalene only in female mice (asterisks in (w)). A fully regenerated bronchiolar epithelium was restored within 14–21 days after injection with naphthalene in both male (c–d, k–l, and s–t) and female (g–h, o–p, and x) mice. Photomicrographs are representative of three to seven mice per gender at each time point after treatment with each dose of naphthalene. All scale bars: 50 µm. Magnification, ×400.

Table 1.

Necrosis scoring of male and female mouse lung sections at different time points after treatment with three different doses of naphthalene

| Time (days) after naphthalene injection | Mean necrosis score/time point after naphthalene injection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low dose (50 mg/kg) | Medium dose (100 mg/kg) | High dose (200 mg/kg) | ||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| 0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| 2 | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 1.03 ± 0.03a,b | 1.20 ± 0.0b | 2.03 ± 0.09a,b | 2.30 ± 0.06b | 2.93 ± 0.05a,b |

| 14 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 1.00 ± 0.05a,b |

| 21 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.20 ± 0.04 |

Histopathological analysis of male and female mouse lung sections at 0, 2, 14, and 21 days after injection with low (50 mg/kg), medium (100 mg/kg), or high dose (200 mg/kg) of naphthalene, as shown in Fig. 1, was performed and the extent of bronchiolar epithelial (Clara) cell necrosis was scored. See the Materials and methods for details. Data are presented as the mean necrosis score ± standard error of three to seven mice per gender at each time point after treatment with each dose of naphthalene. aSignificantly different from that of male mice at same time point after treatment with same dose of naphthalene (P < 0.05). bSignificantly different from the 0 days control group (P < 0.05). The degree of bronchiolar epithelial (Clara) cell necrosis was estimated semi‐quantitatively, and was expressed for each mouse as the mean of 10 random fields within each section (one section per mouse) classified on a scale of 0–3. Scoring criteria were as follows: 0, no necrosis, defined as no detection of necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells exfoliated within the airway lumen; 1, mild, defined as only occasional detection of necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells exfoliated within the airway lumen; 2, moderate, defined as more frequent detection of necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells exfoliated within the airway lumen; 3, severe, defined as very frequent detection of numerous necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells within the airway lumen.

Since H&E analysis of lung injury showed that the most drastic histopathological changes occurred after treatment with high dose of naphthalene (Fig. 1), we decided to focus on this dose only, for studying naphthalene‐induced changes in Clara cells and ciliated cells. In order to follow the fate of Clara cells in male and female mice after naphthalene‐induced bronchiolar epithelial cell injury, immunohistochemical staining for the Clara cell marker, CC10/CCSP, was performed (Fig. 2a–h). Normal bronchiolar epithelium, which stained strongly for CC10/CCSP, was detected in both male and female mice at 0 day (Fig. 2a and 2e, respectively). Necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells, which had exfoliated into the airway lumen, were more abundant in female mice compared to male mice at 2 days post naphthalene injection (Fig. 2f and 2b, respectively). These exfoliated cells also stained very strongly for CC10/CCSP (Fig. 2b,f); this confirms that naphthalene‐induced lung injury was specific to Clara cells. In addition, at 2 days after naphthalene treatment, the diminished bronchiolar epithelium, which had remained intact after Clara cell ablation, stained very weakly for CC10/CCSP in both male and female mice (Fig. 2b and 2f, respectively). Residual injured and necrotic Clara cells were detected in the airway lumen of female mice only at 14 days post naphthalene injection (Fig. 2g). Within 14–21 days after injection with naphthalene, lung injury had cleared up and regenerated bronchiolar epithelium stained very strongly for CC10/CCSP; these conditions suggest Clara cell renewal in both male and female mice (Fig. 2c,d and 2h, respectively).

Figure 2.

(a–h) Immunohistochemical staining for the Clara cell marker: Clara cell 10‐kDa secretory protein (CC10/CCSP) in male (a–d) and female (e–h) mice at 0 (a and e), 2 (b and f), 14 (c and g), and 21 (d and h) days after injection with high dose (200 mg/kg) of naphthalene. At 0 days (control group), a normal bronchiolar epithelium, which stains strongly for CC10/CCSP, was detected in both male (a) and female (e) mice. By 2 days post naphthalene injection in both male and female mice, necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells were detected within the airway lumen, and stained very strongly for CC10/CCSP (asterisks in (b) and (f)). These injured CC10/CCSP‐positive bronchiolar epithelial cells were also detected within the airway lumen at 14 days post naphthalene injection only in female mice (asterisks in (g)). A fully regenerated bronchiolar epithelium, which stains strongly for CC10/CCSP, was restored within 14–21 days after injection with naphthalene in both male (c–d) and female (h) mice. (i–p) Immunohistochemical staining for the ciliated cell marker (FoxJ1) in male (i–l) and female (m–p) mice at 0 (i, m), 2 (j, n), 14 (k, o), and 21 (l, p) days after injection with high dose (200 mg/kg) of naphthalene. At 0 day (control group), a normal bronchiolar epithelium, containing several FoxJ1‐positive (ciliated) and FoxJ1‐negative (Clara) cells, was detected in both male (i) and female (m) mice. By 2 days post naphthalene injection in both male and female mice, injured and exfoliated bronchiolar epithelial cells stained negative for FoxJ1 (asterisks in (j) and (n)), while many of the intact and undamaged bronchiolar epithelial cells were positive for FoxJ1. Within 14–21 days after naphthalene injection, the regenerative response was complete and the bronchiolar epithelium resembled that of the control group in both male (k–l) and female (o–p) mice. Positive staining for both CC10/CCSP and FoxJ1 appears as brown, and sections were counterstained with haematoxylin (×400). Photomicrographs are representative of three to seven mice per gender at each time point after treatment with naphthalene. All scale bars: 50 µm.

In order to follow the fate of ciliated cells in male and female mice after naphthalene‐induced Clara cell injury, immunohistochemical staining for ciliated cell marker (FoxJ1) was performed (Fig. 2i–p). In the 0 day control group, normal bronchiolar epithelium, containing several FoxJ1‐positive (ciliated) cells and FoxJ1‐negative (Clara) cells, was present in both male and female mice (Fig. 2i and 2m, respectively). By 2 days post naphthalene injection, the necrotic bronchiolar epithelial cells detected within the airway lumen stained negatively for FoxJ1in both male and female mice (Fig. 2j and 2n, respectively); this confirms that ciliated cells were not injured by naphthalene treatment even at the high dose used in this study. In addition, many of the residual bronchiolar epithelial cells, which remained intact and uninjured after naphthalene‐induced Clara cell ablation, were positive for FoxJ1, suggesting that ciliated cells can remain unharmed to help protect the denuded bronchiolar epithelial basement membrane in both male and female mice (Fig. 2j and 2n, respectively). Within 14–21 days after injection with naphthalene, regenerative responses were complete and the bronchiolar epithelium resembled that of control groups in both male and female mice (Fig. 2k,l and 2o,p, respectively).

Ki‐67 labelling index

Pulmonary regenerative response to naphthalene‐induced Clara cell ablation was examined by quantification of cell proliferation in the lungs of male and female mice. Immunohistochemical staining for Ki‐67 was first used to determine cell proliferation in the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium and in peribronchiolar interstitium of male and female mice after treatment with low, medium, or high dose of naphthalene (3, 4, 5, respectively).

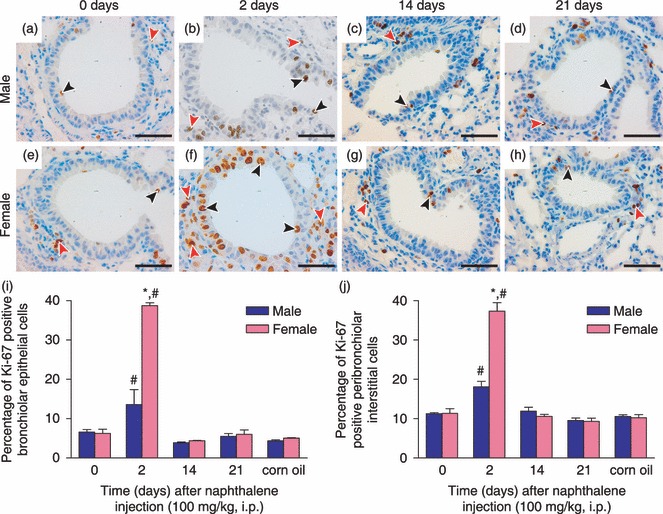

Figure 3.

(a–h) Immunohistochemical staining for the cell proliferation marker: Ki‐67 in male (a–d) and female (e–h) mice at 0 (a, e), 2 (b, f), 14 (c, g), and 21 (d, h) days after injection with low dose (50 mg/kg) of naphthalene. Ki‐67‐positive nuclei are brown, and were detected in both the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium (black arrowheads) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (red arrowheads). Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin (×400). Scale bars: 50 µm. Percentage of Ki‐67‐positive cells was quantified in both the bronchiolar epithelium (i) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (j), as described in the Materials and methods section. Results are presented as means ± standard error of three to seven mice per gender at each time point after treatment with naphthalene or at 2 days after treatment with corn oil (vehicle control). *Significantly different from that of male mice at same time point after naphthalene treatment (P < 0.05). #Significantly different from both of the control groups (0 days and corn oil treatment) (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

(a–h) Immunohistochemical staining for Ki‐67 in male (a–d) and female (e–h) mice at 0 (a, e), 2 (b, f), 14 (c, g), and 21 (d, h) days after injection with medium dose (100 mg/kg) of naphthalene. Ki‐67‐positive nuclei are brown, and were detected in both the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium (black arrowheads) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (red arrowheads). Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin (×400). Scale bars: 50 µm. Percentage of Ki‐67‐positive cells was quantified in both the bronchiolar epithelium (i) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (j), as described in the Materials and methods section. Results are presented as means ± standard error of three to seven mice per gender at each time point after treatment with naphthalene or at 2 days after treatment with corn oil (vehicle control). *Significantly different from that of male mice at same time point after naphthalene treatment (P < 0.05). #Significantly different from both of the control groups (0 days and corn oil treatment) (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

(a–h) Immunohistochemical staining for Ki‐67 in male (a–d) and female (e–h) mice at 0 (a, e), 2 (b, f), 14 (c, g), and 21 (d, h) days after injection with high dose (200 mg/kg) of naphthalene. Ki‐67‐positive nuclei are brown, and were detected in both the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium (black arrowheads) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (red arrowheads). Necrotic Clara cells, which had exfoliated into the bronchiolar lumen, were also present in both male and female mice at 2 days post naphthalene treatment (asterisks in (b) and (f)). Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin (×400). Scale bars: 50 µm. Percentage of Ki‐67‐positive cells was quantified in both the bronchiolar epithelium (i) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (j), as described in the Materials and methods section. Results are presented as means ± standard error of three to seven mice per gender at each time point after treatment with naphthalene or at 2 days after treatment with corn oil (vehicle control). *Significantly different from that of male mice at same time point after naphthalene treatment (P < 0.05). #Significantly different from both of the control groups (0 days and corn oil treatment) (P < 0.05).

In distal bronchiolar airway epithelium, a low baseline Ki‐67 LI level of about 5–7% was observed for all control mice at 0 day after naphthalene injection and 2 days after corn oil injection (Fig. 3i). At 2 days after injection with low dose of naphthalene, Ki‐67 LI was increased to about 22% in female mice, and this value was significantly higher than that of male mice, which had not increased above control levels, and was around 9% (Fig. 3i). At 2 days after injection with medium dose of naphthalene, Ki‐67 LI had now increased significantly above control levels in male mice, but was still significantly less than that of female mice, which increased dramatically to almost 40% (Fig. 4i). Within 14–21 days after injection with both low and medium doses (3, 4, respectively) in male and female mice, cell proliferation of distal bronchiolar airway epithelial cells had decreased to similar levels as those seen in control mice (Ki‐67 LI of about 5–7%). At 2 days after injection with high dose of naphthalene, bronchiolar epithelial cell proliferation increased to over 20% in male mice, significantly greater than Ki‐67 LI observed for female mice, which had not significantly increased above control levels at this time point (Fig. 5i). However, by 14 days after naphthalene injection, Ki‐67 LI increased to almost 20% in female mice, this was now significantly higher than bronchiolar epithelial cell proliferation observed in male mice, which had decreased close to that of control levels (Fig. 5i). By 21 days after injection with high dose of naphthalene, bronchiolar epithelial cell proliferation had decreased to that of control levels (Ki‐67 LI of about 6–7%) in both male and female mice (Fig. 5i).

In the peribronchiolar interstitium, a baseline Ki‐67 LI level of about 10% was observed for all control mice (Fig. 3j). At 2 days after injection with low dose of naphthalene, Ki‐67 LI had increased significantly above control levels in male mice (about 16%); however, it was still significantly less than LI observed for female mice, which had increased to over 30% (Fig. 3j). At 2 days after injection with medium dose of naphthalene, Ki‐67 LI was significantly greater than control levels in male mice, but was still significantly less than that of female mice, which now increased to almost 40% (Fig. 4j). Within 14–21 days after injection with both low and medium doses (3, 4, respectively), cell proliferation of the peribronchiolar interstitium in both male and female mice had decreased to similar levels as those seen in control mice (Ki‐67 LI of about 9–11%). At 2 days after injection with high dose of naphthalene, peribronchiolar interstitial cell proliferation increased to about 33% in male mice, and this was now significantly greater than the Ki‐67 LI observed for female mice, which increased to only 24% (Fig. 5j). However, by 14 days after naphthalene injection, Ki‐67 LI in the peribronchiolar interstitium decreased to near control levels in male mice, while interstitial cell proliferation remained significantly above control levels at about 21% in female mice (Fig. 5j). By 21 days after injection with high dose of naphthalene, peribronchiolar interstitial cell proliferation had decreased to control levels (Ki‐67 LI of about 9–11%) in both male and female mice (Fig. 5j).

PH‐3 mitotic index

In order to confirm the aforementioned gender differences in lung regeneration observed with Ki‐67 LI, immunohistochemical staining for PH‐3 was subsequently used to determine cell mitosis in the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium and in the peribronchiolar interstitium of male and female mice after treatment with low, medium, or high dose of naphthalene (6, 7, 8, respectively).

Figure 6.

(a–h) Immunohistochemical staining for the mitosis marker: phosphohistone‐3 (PH‐3) in male (a–d) and female (e–h) mice at 0 (a, e), 2 (b, f), 14 (c, g), and 21 (d, h) days after injection with low dose (50 mg/kg) of naphthalene. PH‐3‐positive nuclei are brown, and were detected in both the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium (black arrowheads) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (red arrowheads). Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin (×400). Scale bars: 50 µm. Percentage of PH‐3‐positive cells was quantified in both the bronchiolar epithelium (i) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (j), as described in the Materials and methods section. Results are presented as means ± standard error of three to seven mice per gender at each time point after treatment with naphthalene or at 2 days after treatment with corn oil (vehicle control). *Significantly different from that of male mice at same time point after naphthalene treatment (P < 0.05). #Significantly different from both of the control groups (0 days and corn oil treatment) (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

(a–h) Immunohistochemical staining for phosphohistone‐3 (PH‐3) in male (a–d) and female (e–h) mice at 0 (a, e), 2 (b, f), 14 (c, g), and 21 (d, h) days after injection with medium dose (100 mg/kg) of naphthalene. PH‐3‐positive nuclei are brown, and were detected in both the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium (black arrowheads) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (red arrowheads). Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin (×400). Scale bars: 50 µm. Percentage of PH‐3‐positive cells was quantified in both the bronchiolar epithelium (i) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (j), as described in the Materials and methods section. Results are presented as mean ± standard error of three to seven mice per gender at each time point after treatment with naphthalene or at 2 days after treatment with corn oil (vehicle control). *Significantly different from that of male mice at same time point after naphthalene treatment (P < 0.05). #Significantly different from both of the control groups (0 days and corn oil treatment) (P < 0.05).

Figure 8.

(a–h) Immunohistochemical staining for phosphohistone‐3 (PH‐3) in male (a–d) and female (e–h) mice at 0 (a, e), 2 (b, f), 14 (c, g), and 21 (d, h) days after injection with high dose (200 mg/kg) of naphthalene. PH‐3‐positive nuclei are brown, and were detected in both the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium (black arrowheads) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (red arrowheads). Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin (×400). Scale bars: 50 µm. Percentage of PH‐3‐positive cells was quantified in both the bronchiolar epithelium (i) and in the peribronchiolar interstitium (j), as described in the Materials and methods section. Results are presented as mean ± standard error of three to seven mice per gender at each time point after treatment with naphthalene or at 2 days after treatment with corn oil (vehicle control). *Significantly different from that of male mice at same time point after naphthalene treatment (P < 0.05). #Significantly different from both of the control groups (0 days and corn oil treatment) (P < 0.05).

In distal bronchiolar airway epithelium, a low baseline PH‐3 mitotic index (MI) level of about 3–4% was observed for all control mice at 0 day after naphthalene injection and 2 days after corn oil injection (Fig. 6i). At 2 days after injection with low dose of naphthalene, PH‐3 MI increased to about 20% in female mice, and this value was significantly higher than that for male mice, which had not increased above control levels and was around 5% (Fig. 6i). At 2 days after injection with medium dose of naphthalene, PH‐3 MI had now increased significantly above control levels in male mice, but was still significantly less than that of female mice, which increased dramatically to about 36% (Fig. 7i). Within 14–21 days after injection with both low and medium doses (6, 7, respectively), bronchiolar epithelial cell mitosis in both male and female mice had decreased to similar levels to those seen in control mice (PH‐3 MI of about 2–4%). At 2 days after injection with high dose, bronchiolar epithelial cell mitosis increased to almost 20% in male mice, and this was significantly greater than PH‐3 MI observed for female mice, which had not significantly increased above control levels at this time point (Fig. 8i). However, by 14 days after naphthalene injection, PH‐3 MI increased to around 15% in female mice, and this being significantly higher than bronchiolar epithelial cell mitosis observed in male mice, which had decreased close to that of control levels (Fig. 8i). By 21 days after injection with high dose of naphthalene, bronchiolar epithelial cell mitosis had decreased to near control levels (PH‐3 MI of about 5%) in both male and female mice (Fig. 8i).

In peribronchiolar interstitium, baseline PH‐3 MI level of around 9% was observed for all control mice (Fig. 6j). At 2 days after injection with low dose of naphthalene, PH‐3 MI had increased significantly above control levels in male mice (about 14%); however, it was still significantly less than MI observed for female mice, which increased to almost 30% (Fig. 6j). At 2 days after injection with medium dose of naphthalene, PH‐3 MI was significantly greater than control levels in male mice, but was still significantly less than that of female mice, which now increased to about 35% (Fig. 7j). Within 14–21 days after injection with either low or medium dose (6, 7, respectively), peribronchiolar interstitial cell mitosis in both male and female mice had decreased to similar levels as those seen in control mice (PH‐3 MI of about 7–10%). At 2 days after injection with high dose, peribronchiolar interstitial cell mitosis increased to about 30% in male mice, which was significantly greater than PH‐3 MI observed for female mice, which increased to about 21% (Fig. 8j). However, by 14 days after naphthalene injection, PH‐3 MI decreased to near control levels in male mice, while interstitial cell mitosis remained significantly above control levels at about 17% in female mice (Fig. 8j). By 21 days after injection with high dose of naphthalene, peribronchiolar interstitial cell mitosis had decreased to control levels (PH‐3 MI of about 8–9%) in both male and female mice (Fig. 8j).

Discussion

There are many biological factors that can modulate epithelial response to toxicants in airways, including (i) metabolic potential at specific sites for bioactivation and detoxification; (ii) nature of the local inflammatory response; (iii) age of the organism at time of exposure; (iv) history of previous exposure; (v) species and strain of organism exposed; and (vi) gender of exposed organism (40). Although previous studies have shown gender differences in naphthalene metabolism and naphthalene‐induced lung injury in mice (38, 39), very little is known about magnitude of gender on long‐term regenerative responses. In the present study, we have used three different doses of naphthalene in order to obtain a broad range of lung injury and repair responses. We found that female mice were not only more susceptible than male mice to Clara cell injury observed at 2 days after treatment with a very low dose (50 mg/kg) or medium dose (100 mg/kg) of naphthalene, but that both cell proliferation and mitosis were substantially more abundant in distal bronchiolar airway epithelium and in peribronchiolar interstitium of female mice as compared to male mice. Furthermore, by 14–21 days after treatment with low and medium doses, bronchiolar injury had cleared up and low levels of lung tissue regeneration were detected in both male and female mice; these results indicate a timely regenerative response to the two relatively low naphthalene doses. However, after treatment with high dose of naphthalene (200 mg/kg), different lung repair responses were observed. We found that lung regeneration was attenuated and delayed in female mice with bronchiolar epithelial cell proliferation and mitosis not peaking until 14 days, while male mice mounted an adequate and timely regenerative response with cell proliferation and mitosis peaking at 2 days. This delayed lung repair response in female mice may be attributed to the very severe Clara cell damage detected at 2–14 days after treatment with high dose of naphthalene. Female mice are more sensitive than male mice to naphthalene‐induced lung injury, and may have required more time to recover from the massive Clara cell ablation; thus, these cause delayed regenerative response after treatment with high dose of naphthalene. Nevertheless, female mice were eventually able to mount an adequate repair response, and lung regeneration was complete by 21 days after naphthalene treatment.

In the present study, we have used immunohistochemical staining for both Ki‐67 and PH‐3 to assess levels of cell proliferation and mitosis in the lungs (distal bronchiolar airway epithelium and peribronchiolar interstitium) of male and female mice after naphthalene treatment. Levels of lung cell regeneration measured using these two markers showed different values with percentage of PH‐3‐positive cells being slightly lower than percentage of Ki‐67‐positive cells. This can be explained as that these two markers are indicative of different stages of cell cycle. While Ki‐67 is a more general cell proliferation marker and is preferentially expressed during all phases of the cell cycle except for quiescence (41), PH‐3 is a mitosis marker and is specific to M phase only (42). Therefore, it makes sense that MI measured after PH‐3 staining would have a lower percentage of positive cells than LI measured using Ki‐67. Nevertheless, data obtained with both markers showed similar patterns, and the trends in lung regeneration observed in both genders of mice after treatment with the three different doses of naphthalene were conserved. Thus, both Ki‐67 LI data and PH‐3 MI data shown in this study provide strong evidence for gender differences in mouse lung regeneration after naphthalene‐induced Clara cell depletion.

There are many possible explanations for the gender differences in lung repair observed in this study. For instance, female sex hormones, such as oestrogen, may play a role in the pulmonary regenerative response to naphthalene‐induced Clara cell ablation. It is known that oestrogen can induce expression of many drug‐metabolizing isoenzymes in the lungs (2, 5, 7, 13) and, therefore, females have the potential to undergo more metabolic bioactivation of xenobiotics to toxic metabolites than males. Furthermore, studies have shown that hormonal patterns associated with different stages of the oestrous cycle can alter naphthalene metabolism in the lungs of female mice (38), and that metabolism of naphthalene occurs much faster and is associated with a greater extent of lung injury in female mice as compared to male mice (39). Thus, we can only speculate that the more extensive Clara cell injury in female mice, compared to male mice observed in the aforementioned studies and in our study may be due to the fact that females produce substantially more oestrogen than males. Although it has not been directly shown, oestrogen may specifically up‐regulate pulmonary expression of cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 2F2, which is the main enzyme responsible for converting naphthalene into its toxic metabolites, and this may be the reason for previously observed more rapid metabolism of naphthalene in Clara cells of female mice as compared to male mice. Therefore, high oestrogen levels may lead to increased naphthalene metabolism, which in turn can lead to increased injury and repair in lungs of female mice. In addition, both oestrogen receptor‐alpha and oestrogen receptor‐beta are expressed in the airways, and upon binding to its receptors, oestrogen also has the ability to induce lung cell proliferation and differentiation (7). Interestingly, increased oestrogen levels are known risk factors for lung cancer in women (7). It is currently not known if gender differences in lung cell proliferation and mitosis observed in our study are due to gender differences in oestrogen levels. However, this study provides the novel finding that gender‐dependent differences in naphthalene‐induced lung injury can subsequently influence downstream repair kinetics.

Various X‐linked genes involved in the process of lung repair/regeneration may also play a role in gender differences observed in this study. A possible candidate is the gene encoding for gastrin‐releasing peptide receptor (GRPR), which is located on the X‐chromosome near a cluster of genes that escape X‐chromosome inactivation (2, 5, 43). Thus, females have two actively transcribed alleles of GRPR gene compared with only one in males (5). Moreover, a previous study has reported sex differences in expression of GRPR where in the absence of smoking, it is expressed more frequently in the airway cells of women than in men, and in response to tobacco exposure, GRPR expression is activated earlier in women as compared to men (43). There is also increased expression of the GRPR when human airway cells are exposed to oestrogen, suggesting that GRPR could be hormonally regulated (2, 5). This increased expression of GRPR in women is believed to be a contributing factor to their increased susceptibility to tobacco‐induced lung cancer (43). Indeed, signalling through GRPR is highly mitogenic, and we can only speculate that it may account for higher levels of cell proliferation and mitosis detected in lungs of female mice as compared to male mice in our study.

Many different cell types have been shown to play a role in lung regeneration after naphthalene‐induced Clara cell ablation in mice, and those identified to date include basal cells (29, 30), PNECs (23, 31, 32), BASCs (21, 33), ciliated cells (22, 24, 34), peribronchiolar interstitial cells (20, 35), and a pollutant‐resistant subpopulation of Clara cells that retain their expression of Clara cell 10‐kDa secretory protein (CC10/CCSP), also known as variant CC10/CCSP‐expressing (vCE) cells (36, 37).

In the proximal airways, basal cells have been shown to function as a multipotent progenitor capable of renewing naphthalene‐injured tracheal and bronchial epithelium (29, 30). These cells can be found at two main niches within the proximal airways: (i) the submucosal gland ducts and (ii) in cartilage‐intercartilage junctions (18, 44, 45). However, since we observed the most drastic changes in cell proliferation to occur in distal bronchiolar airway epithelium and peribronchiolar interstitium of the lung and did not focus on cell regeneration in proximal airways (trachea and bronchi), basal cells would be unlikely to be involved in gender differences in cell proliferation observed in our study.

In the distal airways, the PNECs, vCE cells, BASCs, ciliated cells, and peribronchiolar interstitial cells have all been shown to partake in lung repair responses following naphthalene‐induced depletion of Clara cells. PNECs are rare airway epithelial cells organized as solitary cells or as innervated clusters of cells known as neuroepithelial bodies (NEB), and have been proposed to serve various functions, including regulation of embryonic/foetal lung growth and maturation through secretion of neuropeptides, such as calcitonin gene‐related peptide and gastrin‐releasing peptide, and bioactive amines, such as serotonin (46). Although PNECs/NEBs have been shown to proliferate after selective ablation of Clara cells, they mainly function as a self‐renewing progenitor population and are unable to repopulate the entire airway, suggesting that PNECs/NEBs are not sufficient for epithelial renewal (23, 31, 32). However, NEBs provide a microenvironment, which has been identified as one of the major niches responsible for harbouring other progenitor cells capable of lung epithelial regeneration (18, 36, 37, 45, 46, 47, 48). For instance, vCE cells have been identified as an important population of label‐retaining progenitor cells located within the NEB microenvironment, and are critical for Clara cell renewal after naphthalene injury (18, 36, 37, 45, 46, 47, 48). These vCE cells are like Clara cells in that they retain their expression of CC10/CCSP; however, unlike Clara cells, they have been characterized as pollutant‐resistant or naphthalene‐resistant cells because they lack detectable cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 2F2 protein, which renders them unable to generate toxic metabolites of naphthalene necessary for inducing cell injury (18, 36, 37, 45, 46, 47, 48). BASCs are also pollutant‐resistant progenitor cells, and have been identified at another important airway niche, known as the bronchoalveolar duct junction (18, 21, 33, 45, 48, 49). These cells have been shown to dually express both the Clara cell marker (CC10/CCSP) and the alveolar type II cell marker (pro‐surfactant protein‐C), and have the ability to respond to both alveolar and bronchiolar injury (18, 21, 49). In the case of bronchiolar injury, BASCs have been shown to be one of the key players involved in renewal of terminal bronchiolar epithelium after naphthalene‐induced ablation of Clara cells (18, 21, 33, 49). Since we focused on repair of the distal bronchiolar airway epithelium after naphthalene‐induced Clara cell injury, it is quite possible that gender differences in lung cell proliferation observed in our study may involve vCE cells and BASCs.

Although still highly controversial, it has been suggested that in an effort to repair naphthalene‐injured bronchiolar epithelium, ciliated cells undergo squamous metaplasia and cell spreading, followed by cell proliferation and transdifferentiation into distinct epithelial cell types (22, 34). However, other investigators carried out lineage tracing studies in order to follow the fate of ciliated cells in mice after naphthalene‐induced Clara cell ablation, and found strong evidence that ciliated cells can transiently change their morphology (i.e. undergo squamous metaplasia) but do not proliferate or transdifferentiate as part of the repair process (24). Thus, it is unlikely that gender differences in lung cell proliferation observed in our study involved ciliated cells. However, we did observe that in both male and female mice, ciliated cells remained intact and uninjured after naphthalene‐induced Clara cell damage and exfoliation, possibly in effort to help protect denuded basement membrane of the bronchiolar epithelium.

It has also been previously shown that peribronchiolar interstitial cells proliferate in response to naphthalene‐induced Clara cell injury in mice (20, 35). These proliferating interstitial cells are believed to be fibroblast‐like cells and/or alveolar macrophages, and have been reported to interact with the basal lamina of adjacent bronchiolar epithelial cells during the repair process (20, 35). In the present study, we found there to be clear gender differences in peribronchiolar interstitial cell proliferation and mitosis following naphthalene administration; however, since our studies of cell regeneration were at light microscope level, we could not further classify the dividing interstitial cells in our mice.

In summary, we have demonstrated that gender plays an important role in the pulmonary regenerative response to naphthalene‐induced Clara cell ablation in mice. Mechanisms involved in lung repair may include various distinctive steps, and have been studied in several laboratories (19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24), but further studies are required to understand the exact role that gender and sex hormones may play in various stages of cell regeneration. Future studies on naphthalene‐induced lung injury and repair in ovariectomized mice are currently underway in our laboratory, and will help to clarify whether female sex hormones play an important role in this process.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to kindly acknowledge Drs Jeffrey Whitsett and Susan Wert for their helpful suggestions on immunohistochemical staining for FoxJ1. This work was supported in part by Operating Grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CCFF), and the Foundation Fighting Blindness–Canada. J. Hu is a CCFF scholar and recipient of the CCFF Zellers Senior Scientist Award, and holds a Premier's Research Excellence Award of Ontario, Canada. J. Oliver is a recipient of the CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarships Doctoral Award.

References

- 1. Carey MA, Card JW, Voltz JW, Arbes SJ Jr, Germolec DR, Korach KS, Zeldin DC (2007) It's all about sex: gender, lung development and lung disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 18, 308–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegfried JM (2001) Women and lung cancer: does oestrogen play a role? Lancet Oncol. 2, 506–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zang EA, Wynder EL (1996) Differences in lung cancer risk between men and women: examination of the evidence. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 88, 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel JD, Bach PB, Kris MG (2004) Lung cancer in US women: a contemporary epidemic. JAMA 291, 1763–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patel JD (2005) Lung cancer in women. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 3212–3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Malhotra S, Lam S, Man SF, Gan WQ, Sin DD (2006) The relationship between stage 1 and 2 non‐small cell lung cancer and lung function in men and women. BMC Pulm. Med. 6, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ben‐Zaken Cohen S, Pare PD, Man SF, Sin DD (2007) The growing burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer in women: examining sex differences in cigarette smoke metabolism. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 176, 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wei Q, Cheng L, Amos CI, Wang LE, Guo Z, Hong WK, Spitz MR (2000) Repair of tobacco carcinogen‐induced DNA adducts and lung cancer risk: a molecular epidemiologic study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92, 1764–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kure EH, Ryberg D, Hewer A, Phillips DH, Skaug V, Baera R, Haugen A (1996) p53 mutations in lung tumours: relationship to gender and lung DNA adduct levels. Carcinogenesis 17, 2201–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corey M, Edwards L, Levison H, Knowles M (1997) Longitudinal analysis of pulmonary function decline in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. 131, 809–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corey M (1996) Survival estimates in cystic fibrosis: snapshots of a moving target. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 21, 149–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Corey M, Farewell V (1996) Determinants of mortality from cystic fibrosis in Canada, 1970–89. Am. J. Epidemiol. 143, 1007–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sin DD, Cohen SB, Day A, Coxson H, Pare PD (2007) Understanding the biological differences in susceptibility to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease between men and women. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 4, 671–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. March TH, Wilder JA, Esparza DC, Cossey PY, Blair LF, Herrera LK, McDonald JD, Campen MJ, Mauderly JL, Seagrave J (2006) Modulators of cigarette smoke‐induced pulmonary emphysema in A/J mice. Toxicol. Sci. 92, 545–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gharaee‐Kermani M, Hatano K, Nozaki Y, Phan SH (2005) Gender‐based differences in bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 166, 1593–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Massaro D, Massaro GD (2004) Estrogen regulates pulmonary alveolar formation, loss, and regeneration in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 287, L1154–L1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Massaro D, Clerch LB, Massaro GD (2007) Estrogen receptor‐α regulates pulmonary alveolar loss and regeneration in female mice: morphometric and gene expression studies. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 293, L222–L228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rawlins EL, Hogan BL (2006) Epithelial stem cells of the lung: privileged few or opportunities for many? Development 133, 2455–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stripp BR, Maxson K, Mera R, Singh G (1995) Plasticity of airway cell proliferation and gene expression after acute naphthalene injury. Am. J. Physiol. 269, L791–L799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van Winkle LS, Buckpitt AR, Nishio SJ, Isaac JM, Plopper CG (1995) Cellular response in naphthalene‐induced Clara cell injury and bronchiolar epithelial repair in mice. Am. J. Physiol. 269, L800–L818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim CF, Jackson EL, Woolfenden AE, Lawrence S, Babar I, Vogel S, Crowley D, Bronson RT, Jacks T (2005) Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell 121, 823–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Park KS, Wells JM, Zorn AM, Wert SE, Laubach VE, Fernandez LG, Whitsett JA (2006) Transdifferentiation of ciliated cells during repair of the respiratory epithelium. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 34, 151–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Linnoila RI, Jensen‐Taubman S, Kazanjian A, Grimes HL (2007) Loss of GFI1 impairs pulmonary neuroendorine cell proliferation, but the neuroendocrine phenotype has limited impact on post‐naphthalene airway repair. Lab. Invest. 87, 336–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rawlins EL, Ostrowski LE, Randell SH, Hogan BL (2007) Lung development and repair: contribution of the ciliated lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 410–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buckpitt A, Buonarati M, Avey LB, Chang AM, Morin D, Plopper CG (1992) Relationship of cytochrome P450 activity to Clara cell cytotoxicity. II. Comparison of stereoselectivity of naphthalene epoxidation in lung and nasal mucosa of mouse, hamster, rat and rhesus monkey. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 261, 364–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Plopper CG, Macklin J, Nishio SJ, Hyde DM, Buckpitt AR (1992) Relationship of cytochrome P‐450 activity to Clara cell cytotoxicity. III. Morphometric comparison of changes in the epithelial populations of terminal bronchioles and lobar bronchi in mice, hamsters, and rats after parenteral administration of naphthalene. Lab. Invest. 67, 553–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Plopper CG, Suverkropp C, Morin D, Nishio S, Buckpitt A (1992) Relationship of cytochrome P‐450 activity to Clara cell cytotoxicity. I. Histopathologic comparison of the respiratory tract of mice, rats and hamsters after parenteral administration of naphthalene. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 261, 353–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Buckpitt A, Chang AM, Weir A, Van Winkle L, Duan X, Philpot R, Plopper C (1995) Relationship of cytochrome P450 activity to Clara cell cytotoxicity. IV. Metabolism of naphthalene and naphthalene oxide in microdissected airways from mice, rats, and hamsters. Mol. Pharmacol. 47, 74–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hong KU, Reynolds SD, Watkins S, Fuchs E, Stripp BR (2004) Basal cells are a multipotent progenitor capable of renewing the bronchial epithelium. Am. J. Pathol. 164, 577–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hong KU, Reynolds SD, Watkins S, Fuchs E, Stripp BR (2004) In vivo differentiation potential of tracheal basal cells: evidence for multipotent and unipotent subpopulations. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 286, L643–L649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peake JL, Reynolds SD, Stripp BR, Stephens KE, Pinkerton KE (2000) Alteration of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells during epithelial repair of naphthalene‐induced airway injury. Am. J. Pathol. 156, 279–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reynolds SD, Hong KU, Giangreco A, Mango GW, Guron C, Morimoto Y, Stripp BR (2000) Conditional clara cell ablation reveals a self‐renewing progenitor function of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 278, L1256–L1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Giangreco A, Reynolds SD, Stripp BR (2002) Terminal bronchioles harbor a unique airway stem cell population that localizes to the bronchoalveolar duct junction. Am. J. Pathol. 161, 173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lawson GW, Van Winkle LS, Toskala E, Senior RM, Parks WC, Plopper CG (2002) Mouse strain modulates the role of the ciliated cell in acute tracheobronchial airway injury‐distal airways. Am. J. Pathol. 160, 315–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Van Winkle LS, Isaac JM, Plopper CG (1997) Distribution of epidermal growth factor receptor and ligands during bronchiolar epithelial repair from naphthalene‐induced Clara cell injury in the mouse. Am. J. Pathol. 151, 443–459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reynolds SD, Giangreco A, Power JH, Stripp BR (2000) Neuroepithelial bodies of pulmonary airways serve as a reservoir of progenitor cells capable of epithelial regeneration. Am. J. Pathol. 156, 269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hong KU, Reynolds SD, Giangreco A, Hurley CM, Stripp BR (2001) Clara cell secretory protein‐expressing cells of the airway neuroepithelial body microenvironment include a label‐retaining subset and are critical for epithelial renewal after progenitor cell depletion. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 24, 671–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stelck RL, Baker GL, Sutherland KM, Van Winkle LS (2005) Estrous cycle alters naphthalene metabolism in female mouse airways. Drug Metab. Dispos. 33, 1597–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Van Winkle LS, Gunderson AD, Shimizu JA, Baker GL, Brown CD (2002) Gender differences in naphthalene metabolism and naphthalene‐induced acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 282, L1122–L1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Plopper CG, Buckpitt A, Evans M, Van Winkle L, Fanucchi M, Smiley‐Jewell S, Lakritz J, West J, Lawson G, Paige R, Miller L, Hyde D (2001) Factors modulating the epithelial response to toxicants in tracheobronchial airways. Toxicology 160, 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Takebayashi S, Nakagawa T, Kojima K, Kim TS, Endo T, Iguchi F, Kita T, Yamamoto N, Ito J (2005) Nuclear translocation of beta‐catenin in developing auditory epithelia of mice. Neuroreport 16, 431–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hendzel MJ, Wei Y, Mancini MA, Van Hooser A, Ranalli T, Brinkley BR, Bazett‐Jones DP, Allis CD (1997) Mitosis‐specific phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates primarily within pericentromeric heterochromatin during G2 and spreads in an ordered fashion coincident with mitotic chromosome condensation. Chromosoma 106, 348–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shriver SP, Bourdeau HA, Gubish CT, Tirpak DL, Davis AL, Luketich JD, Siegfried JM (2000) Sex‐specific expression of gastrin‐releasing peptide receptor: relationship to smoking history and risk of lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92, 24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Engelhardt JF (2001) Stem cell niches in the mouse airway. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 24, 649–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stripp BR, Shapiro SD (2006) Stem cells in lung disease, repair, and the potential for therapeutic interventions: state‐of‐the‐art and future challenges. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 34, 517–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Linnoila RI (2006) Functional facets of the pulmonary neuroendocrine system. Lab. Invest. 86, 425–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bishop AE (2004) Pulmonary epithelial stem cells. Cell Prolif. 37, 89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stripp BR, Reynolds SD (2008) Maintenance and repair of the bronchiolar epithelium. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 5, 328–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim CF (2007) Paving the road for lung stem cell biology: bronchioalveolar stem cells and other putative distal lung stem cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 293, L1092–L1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]