Abstract

Purpose

Disordered eating behavior—dieting, laxative use, fasting, binge eating—is common in college-aged women (11–20%). A documented increase in the number of young women experiencing psychopathology has been blamed on the rise of engagement with social media sites such as Facebook. We predicted that college-aged women’s Facebook intensity (e.g., the amount of time spent on Facebook, number of Facebook friends, and integration of Facebook into daily life), online physical appearance comparison (i.e., comparing one’s appearance to others’ on social media) and online “fat talk” (i.e., talking negatively about one’s body) would be positively associated with their disordered eating behavior.

Methods

In an online survey, 128 college-aged women (81.3% Caucasian, 6.7% Asian, 9.0% African-American, and 3.0% Other) completed items, which measured their disordered eating, Facebook intensity, online physical appearance comparison, online fat talk, body mass index, depression, anxiety, perfectionism, impulsivity, and self-efficacy.

Results

In regression analyses, Facebook intensity, online physical appearance comparison, and online fat talk were significantly and uniquely associated with disordered eating and explained a large percentage of the variance in disordered eating (60%) in conjunction with covariates. However, greater Facebook intensity was associated with decreased disordered eating behavior whereas both online physical appearance comparison and online fat talk were associated with greater disordered eating.

Conclusions

College-aged women who endorsed greater Facebook intensity were less likely to struggle with disordered eating when online physical appearance comparison was accounted for statistically. Facebook intensity may carry both risks and benefits for disordered eating.

Keywords: disordered eating, fat talk, physical appearance comparison, media exposure, social media, Facebook

Disordered eating behavior—dieting, laxative use, fasting, binge eating—is common in college-aged women (11–20%) (1, 2). The advent of social media has led to new lay and research questions about the role of social media use in fostering disordered eating behavior. A documented increase in the number of individuals seeking treatment for disordered eating has been blamed on the rise of social media sites such as Facebook (3, 4). The amount of time adolescents (13–18 years) spend on Facebook has also been significantly associated with their disordered eating behaviors (5, 6). In an experimental study, college-aged women randomized to spend time on Facebook reported greater shape and weight concerns and state anxiety compared with the control group who viewed a neutral website (7). Greater online appearance exposure—the time devoted to photo applications on Facebook—has been associated with greater thin-ideal internalization—the belief that thin bodies are more attractive and of higher status—and a greater desire to be thin (6).

Facebook has a high adoption rate in college-aged women. In the United States in 2012, 90% college-aged women maintained an active presence on Facebook and women aged 18–29 years represented the largest cohort of Facebook users (8). The goal of the present study was to extend the current literature on associations between Facebook use and disordered eating behaviors in three ways. First, we extended the current literature by examining Facebook intensity. Although research demonstrated that individuals who spend greater time using Facebook were more likely to engage in disordered eating behaviors, no studies to our knowledge had examined Facebook intensity, which captures individuals’ emotional connection to the site and the integration of the site into their daily life (5, 6, 9). Given previous research, we predicted that when college-aged women reported greater Facebook intensity, they would also be more likely to report greater disordered eating (5).

Second, we explored the role of online physical appearance. Maladaptive Facebook usage—the tendency to evaluate oneself negatively in comparison to one’s Facebook friends— significantly predicted an increase in young adult women’s binge eating and purging symptoms in a prospective longitudinal study (10). However, it is unclear whether the association between maladaptive Facebook usage and disordered eating is driven by social comparisons (e.g., evaluating oneself on the basis of relationship status) or physical appearance comparisons (e.g., a downward or upward comparison to others on the basis of one’s physical appearance). In previous research, online physical appearance comparison with Facebook friends and distant peers was associated with greater body image concerns and offline physical appearance comparison was associated with greater disordered eating (11, 12). Thus, we hypothesized that online physical appearance comparison would also be associated with greater disordered eating (13).

Third, we explored the role of online fat talk on Facebook. Fat talk refers to negative talk about body size and shape while emphasizing a societal ideal towards thinness (e.g., “My thighs are so disgusting”) (14). Fat talk has become a social norm, a bid for reassurance, and even a bonding activity among young women (15). Fat talk not only reflects body dissatisfaction, but can intensify disordered behaviors (16). We hypothesized that Facebook may represent a new public forum for online fat talk behavior, especially in comments on photos, and that engaging in online fat talk could index disordered eating behavior in college-aged women.

Thus, in the present study, we examined the unique associations between disordered eating and Facebook intensity, online physical appearance comparison, and online fat talk. We examined the associations in models accounting for physical and psychological covariates previously associated with disordered eating (e.g., higher BMI, greater anxiety, depression, perfectionism, negative urgency, lower self-efficacy) (17, 18).

METHOD

Participants

We recruited a total of 169 participants via a university listserv announcement sent to all undergraduate students at a large southeastern university and through social media sites [Southern Smash blog, and Twitter pages, this study’s Facebook Page, Facebook pages for this southeastern university’s residence halls, and Exchanges, the blog for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders. Participants were invited to contribute to a study examining social media activity and health behaviors in college women and directed to the study website Connections. Participants were not compensated for their participation and were primarily drawn from colleges and universities in the US southeast. Inclusion criteria included self-reports of female gender, age between 18–23 years old, enrollment in college, and maintenance of a Facebook account. All races and ethnicities were recruited. Although 169 participants initiated the survey, 75.7% (128 participants) had complete data.

Study Overview

All participants completed the 185-item survey online through a survey URL. Participants consented to take part in the survey by reading the consent form online and checking their agreement. All questions were optional, but participants were reminded if a question was left blank. Once the survey was submitted, the participants’ involvement in the study was complete. The Institutional Review Board at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill approved the survey and study procedures.

Dependent Variables

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q4) (19)

The EDE-Q4 is a 36-item, self-report survey of eating disorder behaviors and cognitions. The Eating Disorders Examination (EDE) is a widely used interview for the assessment and diagnosis of eating disorders (20, 21). Participants rated their behaviors over the past 28 days on a 7-point scale (1=No days, 7=Every day). The EDE-Q4 demonstrates a high level of agreement with EDE in assessing eating psychopathology in the general population and measures dietary restraint, bulimic episodes, and shape and weight concerns (21). The global score is calculated by taking the average of the dietary restraint, bulimic episodes, and shape and weight concerns subscale scores. Global scores at or above 4 indicate clinically severe eating disorder psychopathology. Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

Independent Variables

Facebook Intensity Scale (FBI) (9)

The FBI is an 8-item questionnaire designed to measure one’s emotional connection to Facebook and incorporation of Facebook into his or her daily life. Sample items are, “I feel out of touch when I haven’t logged onto Facebook in a while” and “I would feel sorry if Facebook shut down.” The assessment also includes items that capture the total number of Facebook “friends” and amount of time spent on Facebook per day. Higher scores reflect greater Facebook intensity. Cronbach’s alpha was .87.

Online Physical Appearance Comparison Scale (Online PACS) (13)

The Online PACS (a modified PACS) measured physical appearance comparisons on Facebook. A sample item included, “The best way for a person to know if they are overweight or underweight is to compare their figure to the figure of others in Facebook photographs,” as adapted from “The best way for a person to know if they are overweight or underweight is to compare their figure to the figure of others.” Higher scores indicated greater physical appearance comparison. Cronbach’s alpha was .78.

Online Fat Talk Scale (FTS) (22)

The FTS presents nine scenarios in which women express and respond to weight concerns. Respondents rate on a 5-point scale whether they would respond similarly to the main character Naomi. For the present study, we adapted the FTS to reflect online interactions (e.g., “Naomi and her friends post photographs on Facebook from a recent party or dance. One friend comments that her stomach looks fat in one of the photographs. Another friend writes that she hates her thighs. Naomi replies with something she hates about her own body.”). Cronbach’s alpha was .91.

Covariates

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Participants self-reported their current height (in) and weight (lbs). Participant BMI was calculated according to standard formulas [703 × weight (lb) / (height (in))2].

Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) (23)

The BDI-II (21 items) assesses depressed mood. Total scores between 0–13 are considered minimal range, 14–19 mild, 20–28 moderate, and 29–63 severe. Cronbach’s alpha was .93.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (24)

Only the trait anxiety scale (20 items) was included in the present study. Half of the items were reverse-coded. Item scores were totaled; totals closer to the minimum of 20 indicated low to mild anxiety, and totals closer to the maximum of 80 indicated severe anxiety. Cronbach’s alpha was .94.

Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS) (25)

The MPS is a 35-item inventory on a 5-point Likert scale. Because the “concern over mistakes” subscale has been found to be a strong predictor of disordered eating behaviors, only this subscale was used (26). Item scores were totaled; higher scores reflected greater high perfectionism. Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

(Negative) Urgency, (Lack of) Premeditation, (Lack of) Perseverance, and Sensation Seeking (UPPS-P) Impulsive Behavior Scale: Negative Urgency (27)

The 12-item negative urgency subscale of the UPPS-P indexes a lack of premeditation and perseverance and the presence of sensation-seeking (e.g., “When I feel bad, I will often do things I later regret in order to make myself feel better now.”). Higher scores indicated greater high impulsivity. Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) (28)

The GSE is a 10-item scale designed to assess an individual’s belief in his/her ability to handle, control, and cope with the demands of life. Each item is scored using a 4-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicated greater self-efficacy. Cronbach alpha’s was .89.

Statistical Analyses

We used SPSS to analyze the survey data, and statistical significance was set at p < .05. (29) Independent variables included Facebook intensity, online physical appearance comparison and online fat talk. Covariates included depression, trait anxiety, perfectionism, impulsivity, general self-efficacy. We examined all variables for outliers and removed a single data point for an individual who reported using Facebook actively for 840 minutes (14 hours) per day. The next closest data point was 240 minutes (4 hours) per day. To investigate whether Facebook intensity, online physical appearance comparison, and online fat talk added unique variance to variability in disordered eating behaviors, we conducted a series of multiple regressions adjusted for covariates. With disordered eating as an outcome, we first included our covariates (Model 1; BMI, depression, trait anxiety, perfectionism, impulsivity, and self-efficacy). We then included each independent variable—Facebook intensity (Model 2), online physical appearance comparison (Model 3), and online fat talk (Model 4)—into a separate regression models while controlling for covariates. Our final model (Model 5) included all three independent variables, Facebook intensity, online physical appearance comparison, and online fat talk.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

Participants reported their year in college: 23.1% were freshmen, 20.1% sophomores, 20.1% juniors, and 36.6% seniors. The majority of respondents (81.3%) reported that they were Caucasian, 6.7% Asian, 9.0% African-American, and 3.0% reported other and 4.7% reported they were Latino. On average, participants reported that their household income ranged between $80,000–90,000 per year.

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for measures are presented in Table 1. In general, participants did not report disordered eating behaviors above the clinical threshold for eating disorder psychopathology; average scores were below 4.0 on the global EDE-Q. However, 22 participants (13.6%) had scores at or above 4. Prior EDE-Q studies have used a cut-off of ≥4 as a marker of clinical significance (30). In addition, 16.8% of participants had depression levels in the moderate-to-severe range as measured by the BDI–II (Total score ≥ 20). On average, participants reported that they had 799.48 Facebook friends (Range=35–2380 friends) and that they spent 52.25 minutes per day in the previous week on Facebook (Range=0–240 minutes).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Dependent and Independent Variables and Covariates

| Measure | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | ||

| Disordered Eating (EDEQ4-Global) | 2.13 | 1.43 |

| Independent Variables | ||

| Facebook Intensity | 3.18 | 0.66 |

| Time per day on Facebook (minutes) | 52.25 | 43.97 |

| Number of Facebook friends | 799.48 | 454.20 |

| Online Physical Appearance Comparison | 12.84 | 3.40 |

| Online Fat Talk | 1.64 | 0.63 |

| Covariates | ||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 23.20 | 4.48 |

| Depression symptoms (BDI) | 12.29 | 10.42 |

| Trait Anxiety (STAI) | 38.54 | 12.18 |

| Perfectionism (MPS) | 2.87 | 0.92 |

| Negative Urgency (UPPS) | 26.14 | 3.40 |

| General Self-Efficacy (GSE) | 30.27 | 4.73 |

Correlations between Outcome and Predictor Variables

The zero-order correlations for all analysis variables are presented in Table 2. Online physical appearance comparison, and online fat talk, BMI, depression, anxiety, perfectionism, negative urgency, were positively and significantly correlated with greater endorsement of disordered eating. Participants’ self-efficacy was significantly and inversely correlated with disordered eating. Facebook intensity was positively correlated with online physical appearance comparison.

Table 2.

Correlations between Dependent and Independent Variables and Covariates

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | ||||||||||

| 1. Disordered Eating (EDEQ4) | --- | |||||||||

| Independent Variables | ||||||||||

| 2. Facebook Intensity | −.01 | |||||||||

| 3. Online Physical Appearance Comparison | .69*** | .19* | ||||||||

| 4. Online Fat Talk | .37*** | .17 | .48*** | |||||||

| Covariates | ||||||||||

| 5. Body Mass Index | .28** | .02 | .20* | .09 | ||||||

| 6. Depressive Symptoms (BDI) | .60*** | .02 | .50*** | .28** | .20* | |||||

| 7. Trait Anxiety (STAI) | .55** | .10 | .51*** | .28** | .07 | .74*** | ||||

| 8. Perfectionism (MPS) | .50** | .17 | .64** | .40** | .11 | .56*** | .52*** | |||

| 9. Negative Urgency (UPPS) | .36** | .17 | .43*** | .27** | .26** | .55*** | .45*** | .46*** | ||

| 10. Self-Efficacy (GSE) | −.31*** | .04 | −.32*** | −.23** | −.04 | −.53*** | −.52*** | −.36*** | −.23** | --- |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Contributors to Disordered Eating: Hierarchical Regression

Regression analyses data for disordered eating (EDE-Q Global Score) are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis Predicting Disordered Eating (EDEQ4- Global Score): Standardized Beta Values

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | |||||

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | .20** | .20** | .14* | .17* | .13 |

| Depression (BDI)c | .34** | .32** | .33** | .36*** | .35** |

| Trait Anxiety (STAI)d | .25* | .26* | .14 | .28* | .16 |

| Perfectionism (MPS)e | .24** | .25** | <.001 | .18 | .01 |

| Negative Urgency (UPPS)f | −.10 | −.09 | −.14 | −.15 | −.14 |

| Self-Efficacy (GSE)g | .05 | .06 | .06 | .11 | .10 |

| Independent Variables | |||||

| Facebook Intensity | −.07 | −.12* | |||

| Online Physical Appearance Comparison | .50*** | .49*** | |||

| Online Fat Talk | .16* | .16* | |||

| R2 | .46*** | .47*** | .57*** | .49*** | .60*** |

| F for Δb | 17.4*** | 1.1 | 39.56*** | 4.95* | 13.93*** |

| df | 127 | 121 | 121 | 124 | 118 |

Adjusted for Body Mass Index, Depressive Symptoms, Trait Anxiety, Perfectionism, Negative Urgency, and Self-Efficacy

F statistic for change from unadjusted model

BDI – Beck Depression Inventory;

STAI – State Trait Anxiety Inventory;

MPS = Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale

UPPS – (Negative) Urgency, (Lack of) Premeditation, (Lack of) Perseverance, and Sensation Seeking (UPPS-P) Impulsive Behavior Scale: Negative Urgency ;

GSE – General Self Efficacy Scale

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Model 1: Disordered Eating and Covariates

In Model 1, the covariates together explained 46% of the variance in disordered eating. BMI, depression, trait anxiety, and perfectionism explained unique variance in disordered eating.

Model 2: Disordered Eating and Facebook Intensity

When Facebook intensity was added to the model, it did not explain a significant additional percentage of the variance in disordered eating (<1% of the variance).

Model 3: Disordered Eating and Online Physical Appearance Comparison

In comparison, when online physical appearance comparison was added, it explained an additional 11% of the variance (57% vs. 46%, a significant increase). Only BMI and depression explained unique variance in disordered eating in addition to online physical appearance comparison.

Model 4: Disordered Eating and Online Fat Talk

When online fat talk was added, it explained an additional 3% of the variance (49% vs. 46%, a significant increase) in disordered eating. Only BMI, depression, and trait anxiety explained unique variance in disordered eating in addition to online fat talk.

Model 5. Disordered Eating and Facebook Intensity, Online Physical Appearance Comparison, Online Fat Talk

In Model 5, all three variables—Facebook intensity, online physical appearance comparison, and online fat talk—were added to the model in addition to covariates. When all three were added, together they explained an additional 14% of the variance in disordered eating (60% vs. 46%) above and beyond covariates. Of covariates, only depression continued to explain unique variance in the model.

However, in Model 5 in contrast to Model 2, Facebook intensity now explained unique variance in disordered eating. The negative association between Facebook intensity and disordered eating was the same as in Model 2, but the magnitude of this association increased and was now significant. In contrast, both online physical appearance comparison and online fat talk continued to be positively and uniquely associated with disordered eating.

Post-Hoc Mediation Analyses

We conducted post-hoc mediation analyses to examine whether online physical appearance comparison and online fat talk could be mediating the association between Facebook intensity and disordered eating using the PROCESS macro for SPSS. We continued to include covariates from regression models (31). We hypothesized that our pattern of regression findings—the increase in the degree of association between Facebook intensity and disordered eating from Model 2 to Model 5—might reflect suppression. In suppression, the statistical removal of a meditational path increases the magnitude of the relationship between the presumed independent and dependent variable (31). In this case, the statistical removal of variance explained by online physical appearance comparison and online fat talk (Model 5), may have increased the magnitude of the negative association between Facebook intensity and disordered eating.

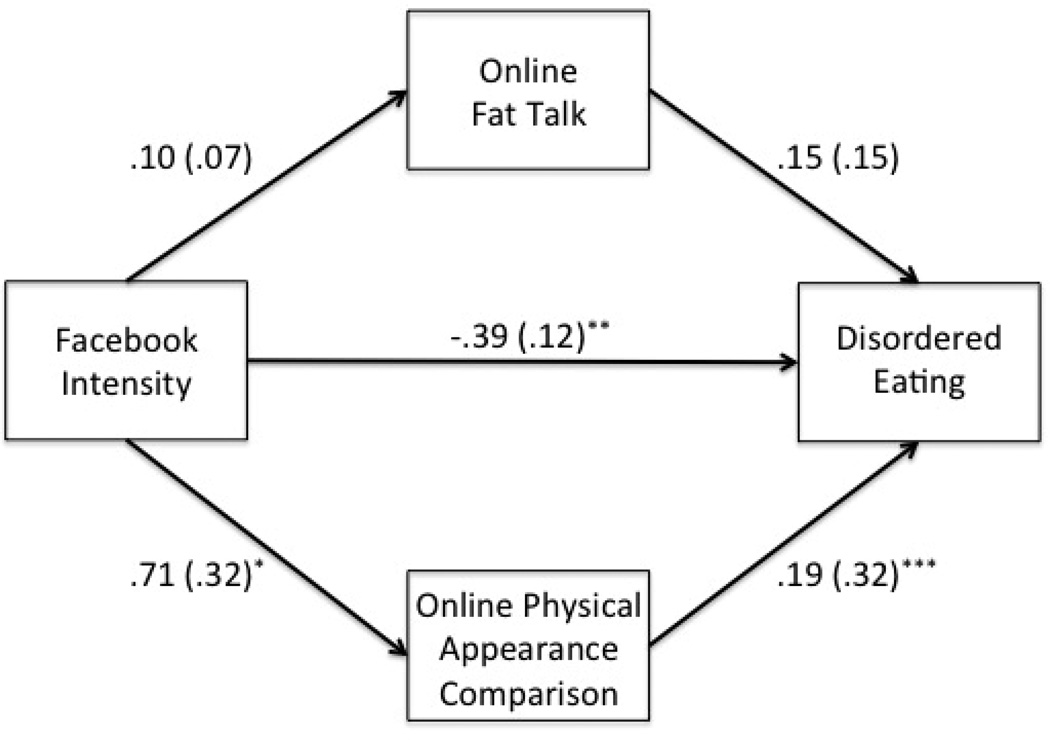

Sixty percent of the variance of disordered eating was explained in mediation analyses (Figure 1). The indirect mediational path between Facebook intensity and disordered eating through online physical appearance comparison was significant. Facebook intensity was significantly positively associated with physical appearance comparison. In turn, online physical appearance comparison was significantly positively associated with greater disordered eating. In contrast, the meditational path through online fat talk was not significant.

Figure 1.

Post-Hoc Mediation Analyses. Online Physical Appearance Comparison Mediates the Association between Facebook Intensity and Disordered Eating (EDEQ4-Global Score) presented in Standardized Beta Values (standard error).

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Consistent with our regression findings, the direct path between Facebook intensity and disordered eating was also significant. When the meditational path through online physical appearance comparison was accounted for, there was a negative association between Facebook intensity and disordered eating. Participants who endorsed greater Facebook intensity, endorsed less disordered eating behavior but only when the meditational path through physical appearance comparison was accounted for.

Conclusions

We hypothesized that greater Facebook intensity would be associated with greater disordered eating behavior. However, in mediation analyses, we found that the association between Facebook intensity and disordered eating was more complicated than we anticipated. In some ways, Facebook intensity—an individual’s emotional connection and integration of the site into his or her daily life—appears to be a double-edged sword for disordered eating behavior. On the one hand, Facebook intensity was associated with increased online physical appearance comparison, which in turn was associated with greater disordered eating. These findings extend recent research which found that amount time spent on Facebook was associated with more frequent upward physical appearance comparison—judging one’s own appearance to be worse than close friends and peers—which, in turn, was associated with greater body image concerns. Because Facebook presents new opportunities to review one’s own and others’ appearance, time spent on Facebook may foster online physical appearance comparisons between friends and peers.

On the other hand, we also found that Facebook intensity and disordered eating were negatively associated once the meditational path of physical appearance comparison was accounted for statistically (5, 6). College-aged women who endorsed greater Facebook intensity were significantly less likely to report disordered eating behaviors in the absence of physical appearance comparison.

Our findings contrast with the literature regarding the association between amount of time on Facebook and disordered eating (5, 6). We hypothesize that this might be due to the variation in how individuals can spend their time. Simply recording the amount of time spent on Facebook may not capture differences in how and whether people engage in social communication with friends, family, and peers while on the site. In previous studies of Internet use and mental health, greater use of the Internet for communication purposes predicted less depression one year later, use for non-communication purposes predicted greater depression, post-partum depression, and social anxiety (32–34). Moreover, greater Facebook intensity has also been associated with building greater bridging social capital—loose connections with individuals who provide information—and bonding social capital—emotionally close relationships with family and close friends—in college-aged students (9). Facebook engagement can also be a tool to cultivate social closeness and decrease loneliness (35, 36).

It may be that when Facebook is not used as a tool to measure and compare oneself physically against friends and peers, greater Facebook intensity could lead to greater social and emotional support and in turn, less loneliness. Loneliness has been found to be positively associated with disordered eating and is also an independent risk factor for later disordered eating (37, 38). Thus, greater emotional bonds with friends and family could result in less disordered eating behavior. Or it may be that decreased Facebook intensity is a consequence of greater disordered eating behaviors; the cognitions associated with disordered eating may interfere with initiating and maintaining social relationships via Facebook (37, 38).

Limitations

Consistent with the previous literature, we found that online physical appearance and online fat talk were significantly associated with variance in disordered eating behavior. Previous studies have demonstrated that young women who engage in greater physical appearance comparison and fat talk are more likely to engage in greater disordered eating and thus, it is perhaps unsurprising that this behavior extends to online contexts as well (15, 16). However, because this study did not examine offline physical appearance comparison and fat talk, we were unable to examine whether online behavior explained unique variance above and beyond offline behavior.

Moreover, regardless of the positive meditational path for disordered eating, because these are cross-sectional data, we are unable to determine the direction of the association. Although Figure 1 includes directional paths between Facebook intensity, physical appearance comparison and disordered eating, we cannot presume that these paths are causal. Future longitudinal studies would be necessary in order to make causal inferences. In addition, some have suggested that mediation analyses with cross-sectional data may lead to systematic biases and misleading effect sizes (39).

We also measured participant’s self-reported tendencies to engage in physical appearance comparisons and fat talk online and did not obtain data about these behaviors from Facebook directly. No rater interviews took place, which may have affected the validity of responses.

There are several factors that could limit the generalizability of the current study. Future study is necessary to examine the observed associations in males, community samples, clinical samples, and more racially and socioeconomically diverse samples. The narrow age range of the sample in the present study and relatively modest sample size also limits generalizability. Furthermore, only 75.1% of participants who began the survey completed it. It may be that the survey was too long, leading to our oversampling participants with personality characteristics that led them to complete the survey. Women who were willing to complete the survey might have also been influenced by the survey’s focus on body image and online social media use.

Future Directions

Having grown up during the digital age, today’s adolescents and young adults, termed “digital natives” because of their facility with digital media, share much of their lives on social media networks such as Facebook (8, 40). Future research should address how physical appearance comparisons occur on Facebook and other photography sharing sites such as Instagram, Tumblr and Pinterest. Are young women posting pictures of themselves in order to request “likes” and comments in order to covertly compare their appearance to friends, family, and peers? Does Facebook simply reflect offline physical appearance comparison or does it magnify young women’s tendencies to engage in appearance comparison?

Highlights.

Facebook intensity may carry both risks and benefits for college-aged women.

Online physical appearance comparison mediates the association between Facebook intensity and disordered eating.

When online physical appearance comparison is accounted for, greater Facebook intensity is associated with less disordered eating.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge undergraduate research interns in the UNC Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders, Lindsey Zink and Sarah Boesch, for their help with survey design and promotion. Dr. Beth Kurtz-Costes, Dr. Mark Hollins, Dr. Don Baucom, and Dr. Anna Bardone-Cone provided additional mentoring to Ms. Walker. Finally, we extend gratitude to all of the study participants for their willingness to contribute their time and thoughts to the survey. Dr. Zerwas is supported by a NIMH training grant (K01MH100435) and no other material or financial support was provided for the study. Dr. Bulik is a consultant for Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Implications and Contribution

Facebook intensity may carry both risks and benefits for college-aged women. Facebook intensity may be protective for or reflect decreased disordered eating behavior, but only in the absence of physical appearance comparisons.

REFERENCES

- 1.Field AE, Sonneville KR, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Eddy KT, Camargo CA, Jr, et al. Prospective associations of concerns about physique and the development of obesity, binge drinking, and drug use among adolescent boys and young adult men. JAMA pediatrics. 2014 Jan;168(1):34–39. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2915. PubMed PMID: 24190655. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3947325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonneville KR, Horton NJ, Micali N, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Solmi F, et al. Longitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults: does loss of control matter? JAMA pediatrics. 2013 Feb;167(2):149–155. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.12. PubMed PMID: 23229786. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3654655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dugan E. Exclusive: Eating disorders soar among teens - and social media is to blame. The Independent. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Micali N, Hagberg KW, Petersen I, Treasure JL. The incidence of eating disorders in the UK in 2000–2009: findings from the General Practice Research Database. BMJ open. 2013;3(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002646. PubMed PMID: 23793681. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3657659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiggemann M, Slater A. NetGirls: the Internet, Facebook, and body image concern in adolescent girls. The International journal of eating disorders. 2013 Sep;46(6):630–633. doi: 10.1002/eat.22141. PubMed PMID: 23712456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meier EP, Gray J. Facebook photo activity associated with body image disturbance in adolescent girls. Cyberpsychology, behavior and social networking. 2014 Apr;17(4):199–206. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0305. PubMed PMID: 24237288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mabe AG, Forney KJ, Keel PK. Do you “like” my photo? Facebook use maintains eating disorder risk. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2014;47(5):516–523. doi: 10.1002/eat.22254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duggan M, Brenner J. The Demographics of Social Media Users – 2012. Pew Research Center. 2013 [cited 2014 July 11, 2014]. Available from: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Social-media-users.aspx.

- 9.Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college student’s use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2007;12:1143–1168. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith AR, Hames JL, Joiner TE., Jr Status update: maladaptive Facebook usage predicts increases in body dissatisfaction and bulimic symptoms. Journal of affective disorders. 2013 Jul;149(1–3):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.032. PubMed PMID: 23453676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fardouly J, Vartanian LR. Negative comparisons about one's appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body image. 2015 Jan;12:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.10.004. PubMed PMID: 25462886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leahey TM, Crowther JH, Ciesla JA. An ecological momentary assessment of the effects of weight and shape social comparisons on women with eating pathology, high body dissatisfaction, and low body dissatisfaction. Behav Ther. 2011 Jun;42(2):197–210. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.07.003. PubMed PMID: 21496506. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3491066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaefer LM, Thompson JK. The development and validation of the Physical Appearance Comparison Scale-Revised (PACS-R) Eating behaviors. 2014 Apr;15(2):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.01.001. PubMed PMID: 24854806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nichter M, Vuckovic N. Fat talk. In: NS, editor. Many mirror: Body image and social relations. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1994. pp. 109–131. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Britton LE, Martz DM, Bazzini DG, Curtin LA, Leashomb A. Fat talk and self-presentation of body image: Is there a social norm for women to self-degrade? Body image. 2006 Sep;3(3):247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.05.006. PubMed PMID: 18089227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salk RH, Engeln-Maddox R. “If you’re fat, then I’m humongous!”: Frequency, content, and impact of fat talk among college women. Psychology of women quarterly. 2011;35(18–28) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Combs JL, Pearson CM, Smith GT. A risk model for preadolescent disordered eating. The International journal of eating disorders. 2011 Nov;44(7):596–604. doi: 10.1002/eat.20851. PubMed PMID: 21997422. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3117119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loth KA, MacLehose R, Bucchianeri M, Crow S, Neumark-Sztainer D. Predictors of Dieting and Disordered Eating Behaviors From Adolescence to Young Adulthood. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2014 Jun 9; doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.016. PubMed PMID: 24925491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter JC, Stewart DA, Fairburn CG. Eating disorder examination questionnaire: norms for young adolescent girls. Behaviour research and therapy. 2001 May;39(5):625–632. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00033-4. PubMed PMID: 11341255. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for young adult women. Behaviour research and therapy. 2006 Jan;44(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.12.003. PubMed PMID: 16301014. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJ. Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behaviour research and therapy. 2004 May;42(5):551–567. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X. PubMed PMID: 15033501. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacDonald Clarke P, Murnen SK, Smolak L. Development and psychometric evaluation of a quantitative measure of “fat talk”. Body image. 2010 Jan;7(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.09.006. PubMed PMID: 19846356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) San Antonio, TX: Psychology Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Luchene R. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: Test manual for Form X. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frost R, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990;14(5):449–68. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bulik CM, Tozzi F, Anderson C, Mazzeo SE, Aggen S, Sullivan PF. The relation between eating disorders and components of perfectionism. The American journal of psychiatry. 2003 Feb;160(2):366–368. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.366. PubMed PMID: 12562586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. Understanding the role of impulsivity and externalizing psychopathology in alcohol abuse: application of the UPPS impulsive behavior scale. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2003 Aug;11(3):210–217. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.210. PubMed PMID: 12940500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwarzer RMJ. Generalized self-efficacy scale. Casual and control beliefs. In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, editors. Measures in Health Psychology: A user’s portfolio Causal and control beliefs. Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON; 1995. pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corp. I. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh Released 2013. I. Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luce KH, Crowther JH, Pole M. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for undergraduate women. The International journal of eating disorders. 2008 Apr;41(3):273–276. doi: 10.1002/eat.20504. PubMed PMID: 18213686. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes AF. In: Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Little TD, editor. New York City, NY: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selfhout MH, Branje SJ, Delsing M, ter Bogt TF, Meeus WH. Different types of Internet use, depression, and social anxiety: the role of perceived friendship quality. Journal of adolescence. 2009 Aug;32(4):819–833. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.011. PubMed PMID: 19027940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Choudhury M, Counts S, Horvitz E, Hoff A. Characterizing and Predicting Postpartum Depression from Shared Facebook Data; Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work & social computing (CSCW ‘14); 2014. pp. 626–638. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCord B, Rodebaugh TL, Levinson CA. Facebook: Social uses and anxiety. Computers in Human Behaviour. 2014;34:23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burke M, Kraut R. Growing Closer on Facebook: Changes in Tie Strength Through Social Network Site Use; Proceedings of the 32nd international conference on human factors in computing systems (CHI ‘14).2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burke M, Marlow C, Lento T. Social Network Activity and Social Well-Being; Proceedings of the 28th nd international conference on human factors in computing systems (CHI ‘10).2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine MP. Loneliness and eating disorders. The Journal of psychology. 2012 Jan-Apr;146(1–2):243–257. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.606435. PubMed PMID: 22303623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rotenberg KJ, Flood D. Loneliness, dysphoria, dietary restraint, and eating behavior. The International journal of eating disorders. 1999 Jan;25(1):55–64. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199901)25:1<55::aid-eat7>3.0.co;2-#. PubMed PMID: 9924653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological methods. 2007 Mar;12(1):23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. PubMed PMID: 17402810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prensky M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon. 2001;9(5):1–6. [Google Scholar]