Abstract

Motivation: RNA-Seq experiments have revealed a multitude of novel ncRNAs. The gold standard for their analysis based on simultaneous alignment and folding suffers from extreme time complexity of . Subsequently, numerous faster ‘Sankoff-style’ approaches have been suggested. Commonly, the performance of such methods relies on sequence-based heuristics that restrict the search space to optimal or near-optimal sequence alignments; however, the accuracy of sequence-based methods breaks down for RNAs with sequence identities below 60%. Alignment approaches like LocARNA that do not require sequence-based heuristics, have been limited to high complexity ( quartic time).

Results: Breaking this barrier, we introduce the novel Sankoff-style algorithm ‘sparsified prediction and alignment of RNAs based on their structure ensembles (SPARSE)’, which runs in quadratic time without sequence-based heuristics. To achieve this low complexity, on par with sequence alignment algorithms, SPARSE features strong sparsification based on structural properties of the RNA ensembles. Following PMcomp, SPARSE gains further speed-up from lightweight energy computation. Although all existing lightweight Sankoff-style methods restrict Sankoff’s original model by disallowing loop deletions and insertions, SPARSE transfers the Sankoff algorithm to the lightweight energy model completely for the first time. Compared with LocARNA, SPARSE achieves similar alignment and better folding quality in significantly less time (speedup: 3.7). At similar run-time, it aligns low sequence identity instances substantially more accurate than RAF, which uses sequence-based heuristics.

Availability and implementation: SPARSE is freely available at http://www.bioinf.uni-freiburg.de/Software/SPARSE.

Contact: backofen@informatik.uni-freiburg.de

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

The majority of transcripts are non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), which unlike mRNAs do not code for proteins. ncRNAs are associated with a large range of important cellular functions; furthermore, there is increasing evidence of pervasive transcription (e.g. Jacquier, 2009; Clark et al., 2011). Particularly, up to 450 000 ncRNAs have been predicted in the human genome alone (Rederstorff et al., 2010).

Analyzing the huge amount of RNA sequences poses major challenges for bioinformatics; particularly, since the sequence of related ncRNAs is often conserved only weakly, while the RNAs can still share a strongly conserved consensus structure. Therefore, taking sequence and structure similarity into account is indispensable for ncRNA analysis (Will et al., 2007; Torarinsson et al., 2007; Shi et al., 2009; Tseng et al., 2009; Saito et al., 2011; Parker et al., 2011). However, accurate methods for this purpose have extreme computational costs.

The gold standard for RNA alignment has been introduced by Sankoff (1985). Because structure prediction and alignment of RNAs depend on each other, Sankoff’s approach solves the alignment and folding problem simultaneously. For two RNA sequences, it finds two energetically favorable structures of the same shape together with a good alignment that reflects the similarity of the structures. For this purpose, Sankoff composes its objective function from a sequence alignment score and the free energies of the two structures. Because of the extreme time complexity of this algorithm, numerous Sankoff-like strategies have been developed aiming to speed up Sankoff’s task, while preserving accuracy as much as possible.

A major class of such methods utilizes information from sequence-based alignment to reduce the search space for the computationally much more expensive alignment and folding algorithm. This idea was introduced in Holmes (2005), and later refined by Dowell and Eddy (2006) and Harmanci et al. (2007). The latter restricts the alignment space to an envelope around the base matches, whose sequence alignment probabilities exceed a fixed cutoff. Generally, such approaches have to cope with the well-known fact that sequence alignment fails for sequence identities below 60% (Gardner et al., 2005). Consequently, sequence alignments can provide hints at the optimal structure-based alignment, but are potentially far-off. Moreover, even with such improvements Sankoff-like methods remain too expensive for large analysis tasks like clustering putative ncRNAs in large datasets, e.g. the entire human transcriptome or even meta-genomics data.

PMcomp (Hofacker et al., 2004) suggested a fundamentally different route to faster RNA alignment. It introduced a new Sankoff-like scoring model that enables lightweight computation. For this purpose, it employs a base pair-based energy model instead of the original loop-based energy model. Furthermore, PMcomp simplifies Sankoff’s model by predicting only a single consensus structure. Tools like LocARNA (Will et al., 2007), FoldAlignM (Torarinsson et al., 2007) and LocARNA-P (Will et al., 2012) build on the PMcomp model, but additionally sparsify the folding spaces of both RNAs, resulting in time complexity. CARNA (Sorescu et al., 2012) extends the PMcomp model to pseudoknot structures. RAF (Do et al., 2008) combined the ideas of Harmanci et al. (2007) and Hofacker et al. (2004), resulting in a lightweight Sankoff-variant with sequence-based speed up.

1.1 Contributions

In this work, we introduce the novel lightweight Sankoff-style approach SPARSE (sparsified prediction and alignment of RNAs based on their structure ensembles) with quadratic time complexity. Achieving the same complexity as sequence alignment with SPARSE is a breakthrough for RNA analysis, because this profound performance gain works without sequence-based heuristics. On the contrary, it is purely based on information from the RNAs’ structural ensembles. Consequently, the technique is applicable without compromising the alignment quality in the low sequence identity zone.

Going beyond LocARNA, which sparsifies based on base pair probabilities, SPARSE additionally sparsifies based on conditional probabilities of bases and base pairs within loops (Otto et al., 2014). The latter results in a quadratic time improvement over LocARNA, which already improved by a quadratic factor over Sankoff’s algorithm; this results in the quadratic time complexity of SPARSE, a quartic speedup over the original Sankoff algorithm.

Concretely, SPARSE sparsifies the novel Sankoff-style algorithm prediction and alignment of RNAs based on their structure ensembles (PARSE), which—like PMcomp—supports lightweight computation. Going beyond PMcomp, it predicts two potentially different structures for the two RNA sequences, supporting insertions and deletions of loops. The dependencies between these structures and the alignment are exactly the same as in the original problem formulation of Sankoff. Thus, the increased flexibility of PARSE over the PMcomp-like previous RNA alignment approaches is an important contribution by itself. We show that the novel problem can be efficiently solved by dynamic programming. Moreover, we present a model and algorithm for affine gap costs that distinguishes insertions and deletions of single bases and entire loops.

Based on SPARSE, we furthermore develop a fast multiple RNA alignment approach. In our benchmarks, compared with LocARNA, the much faster SPARSE computes alignments of similar quality with improved folding quality. Compared with RAF (Do et al., 2008), SPARSE is similarly fast (speedup over LocARNA of 4.2 versus 3.7) and has the same time complexity, but provides superior alignment quality in the hard case of low sequence identity.

2 Methods

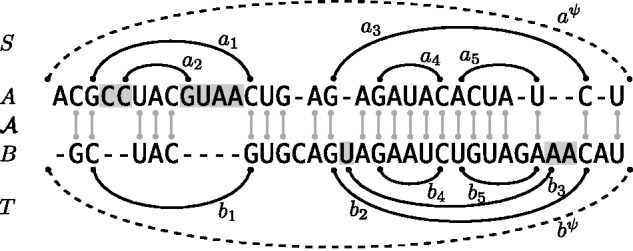

Figure 1 illustrates the subsequent fundamental preliminaries.

Fig. 1.

Example alignment of two RNA sequences A and B together with (non-crossing) structures and . We highlight the positions in the loop closed by a1 and in the loop closed by b2. The base pair a1 is the parent of the highlighted positions in A and of a2. The base pair a1 closes a 2-loop; a2, a 1-loop and a3, a multiloop. The latter is a 3-loop, since a3 has two inner base pairs (a4 and a5.) Note that the structure alignment triple covers the external base pairs and as well as the inner base pairs of the two multiloops. Finally, deletes the entire 2-loop of a1 and inserts the entire 2-loop of b2

RNAs

An RNA sequence A is a string over the alphabet with length . We denote the base at the i-th position of A by ; the substring from position i to j, by ; such substrings of RNA sequences are subsequently called subsequences. A base pair a of A is a pair . A non-crossing RNA structure of A, in the following called structure, is a set of base pairs, where each two different base pairs (i, j) and of do not share any end, i.e. and are pairwise different, and base pairs of do not cross, i.e. there are no with . For reasons of simplicity, we introduce a pseudo base pair , which formally closes the external loop of A. Although does not satisfy , it is otherwise handled like a base pair of A. The position k of A is paired according to , iff there exists such that or . Otherwise k is unpaired.

Loops

For any position k of A, we define the parent of k in , written , as the with i < k < j such that there does not exist any with . Analogously, the parent of a base pair a in , written , is the parent of (or, equivalently, the parent of ). A position k in A or base pair is in the loop closed by a iff , external according to iff , otherwise internal. Furthermore, for a base pair , the loop closed by a consists of the positions . In a structure , a k-loop is a loop with closing base pair a and k−1 inner base pairs , where . A multiloop is a k-loop where k > 2.

Alignments

An alignment of RNA sequences A and B consists of a set of edges written as pairs (i, k), where i is a position in , and k a position in B. Alignment edges do not cross, i.e. for all and . Usually, we consider alignments together with structures of A and of B, forming the triple .

The position i of A is called deleted by , iff there is no k of B s.t. k of B is inserted by , iff there is no i of A s.t. . Positions that are neither deleted nor inserted by are covered by . Analogously, we call a base pair covered by , iff there is a base pair , s.t. symmetrically, we define covered by for base pairs . A base pair (i, j) is called inserted (deleted), iff i and j are inserted (deleted), respectively. matches two positions i and k to each other, iff . Two base pairs are matched to each other by , iff matches their left and right ends to each other.

For 2-loops, we define the notion of insertion or deletion of entire loops. deletes (inserts) the entire 2-loop closed by the base pair , iff it deletes (inserts) all bases in , respectively.

2.1 Lightweight Sankoff-style alignment

Given two RNA sequences A and B (of respective sizes n and m), Sankoff’s problem of simultaneous alignment and folding (Sankoff, 1985) asks for an alignment and RNA structures and for both sequences that simultaneously optimize a score of the form ‘energy of + energy of + sequence edit distance’ in a loop-based energy model (Mathews et al., 1999). Importantly, the alignment and the structures and are not independent of each other: Sankoff requires that all external base pairs and interior base pairs of multiloops of both RNAs are covered by . Moreover, Sankoff (1985) requires that any k-loop (k > 2) is ‘aligned with a single k-loop in the other structure’, whereas 2-loops can be flexibly ‘inserted or deleted in toto’ to align stems of different length. Due to these conditions, aligned multiloops are of the same degree, which preserves the shape [called branching configuration in Sankoff (1985)] of the RNA structures.

2.1.1 PMcomp—a lightweight and simplified Sankoff variant

PMcomp (Hofacker et al., 2004) transfers Sankoff’s idea to a lightweight energy model based on base pairs, which allows much faster computation. However, PMcomp simplifies the problem even more by introducing a one-to-one dependency between the predicted structures for and . In consequence, PMcomp predicts only a single consensus structure, whereas Sankoff much more flexibly predicts two compatible structures of A and B. We are going to show that PMcomp’s second simplification (namely, to predict only the consensus structure) is not required for fast computation and even more has adverse effects.

In the simplified energy model of PMcomp, the energy of a structure is the sum of energy-like weights of the single base pairs in each structure. Because PMcomp defines as log odds of the base pair probability pij (McCaskill, 1990), the model effectively multiplies single base pair probabilities. Here, PMcomp follows the general idea to simplify probability calculations by assuming independence. Otherwise PMcomp, like the original Sankoff algorithm, optimizes a score composed of the sequence similarity and energies.

We rephrase the alignment and folding score of PMcomp, which is assigned to an alignment and RNA structures and , as

| (1) |

where σ is the base similarity, γ is the gap penalty () and is the number of insertion and deletions in .

Due to its second simplification of Sankoff, PMcomp maximizes this score only over the that cover all base pairs in and . This is a strong restriction compared with the more expressive Sankoff algorithm, which requires only that the interior base pairs of multiloops and the external base pairs are covered by . Thus, while Sankoff allows flexibly aligning stems of different lengths due to insertion and deletion of 2-loops, PMcomp cannot handle loop deletions and insertions at all.

2.1.2 PARSE—lightweight and flexible folding and alignment

In the novel algorithm PARSE, we overcome the limitations of PMcomp, maximizing the score of Equation (1) with the full flexibility of Sankoff’s specification in terms of dependencies between alignment and predicted structures. Here, we paraphrase Sankoff’s constraints using our notation and terminology.

Definition 1 —

(Sankoff’s Dependencies Between Alignment and Structures). Let A and B be sequences; of A and of B, structures; and , an alignment of A and B. is a structure alignment triple of A and B (satisfying Sankoff’s dependencies), iff for each base pair and

covers a or deletes the entire loop of

covers b or inserts the entire loop of

in (1) and (2), the deleted or inserted loops have to be 2-loops.

Figure 1 shows a structure alignment triple. The definition makes explicit that base pairs are inserted or deleted only together with their entire 2-loop. This enables predicting stems of different length and align them to each other. At the same time, the two predicted structures cannot differ arbitrarily, but must have the same shape.

2.1.3 Realistic gap cost

Because PARSE supports insertion and deletion (indel) of entire loops, which—unlike base indels—correspond to elongation or shortening of stems in the RNA structure, it is reasonable to distinguish the different evolutionary events of base indel and loop indel in our scoring function. Technically, we introduce two different gap penalties for gaps due to base indels and for gaps due to loop indels. To produce biologically relevant alignments, we extend the above score to support affine gap costs. The different nature of loop indels and base indels suggests two different gap opening penalties and . Thus, in addition to the regular gap opening costs for base indels, we penalize the change of structure by loop indels with a specific loop gap opening cost.

3 Algorithms

In general, the structures and are selected from respective sets of possible base pairs and of sizes N and M. For example, and could consist of all canonical base pairs, but subsequently we are going to sparsify those sets. In our context, we generally assume that and are sparse subsets of all possible base pairs. For example, in LocARNA (Will et al., 2007), and consist of—in the sequence length—only linearly many base pairs due to filtering by a fixed threshold probability.

3.1 A sparsification perspective on PMcomp

Originally, PMcomp was presented (Hofacker et al., 2004) without sparsification in mind, defining dynamic programming matrices indexed by the ends of the aligned subsequences and . To make the correspondence to base pairs in and explicit, we define matrix entries that represent the scores of matching the two base pairs a and b and aligning the two enclosed subsequences. Each is computed from entries that store the best score of any two structures and alignment of subsequences and , where all base pairs in and are covered by ; subsequence scores are defined in the appendix.

The PMcomp algorithm is defined by recurrences for all , i (), and k () (Recall that we simplified the score; still, the original recursions are easily obtained by adding the base pair match contribution to .):

The score of the best pair of consensus structure and alignment of A and B is ; recall that and denote the pseudo-base pairs covering the entire sequences A and B. The alignment and structures themselves are obtained by traceback.

Notably, these recursions can be evaluated in space—i.e. space depends on the respective lengths of A and B and sizes N and M of the sets and of considered base pairs. This space complexity is realized in the same way as in LocARNA: at each time, only one matrix needs to be represented in space, since one matrix recurses only to itself and , but does not depend on other matrices. Even the traceback does not require to store all matrices, because recomputing the matrices on the trace is comparably inexpensive.

The time complexity is dominated by computing the matrices. Evaluating a single matrix takes time. Because, the straightforward evaluation of PMcomp’s recursions computes NM such matrices, this results in . Assuming a linear number of base pairs in and (as it holds for LocARNA), this yields time.

However, this evaluation strategy would consider certain subsequences repeatedly, namely as prefixes of different loops, albeit their scores are identical: by definition, the matrices and share common entries, if their base pairs share the same left ends, i.e. and ; thus, LocARNA combines the computation of such matrices. Although (assuming N and M are linearly bound) this does not change the complexity, it substantially speeds up the computation in practice.

3.2 The PARSE core algorithm

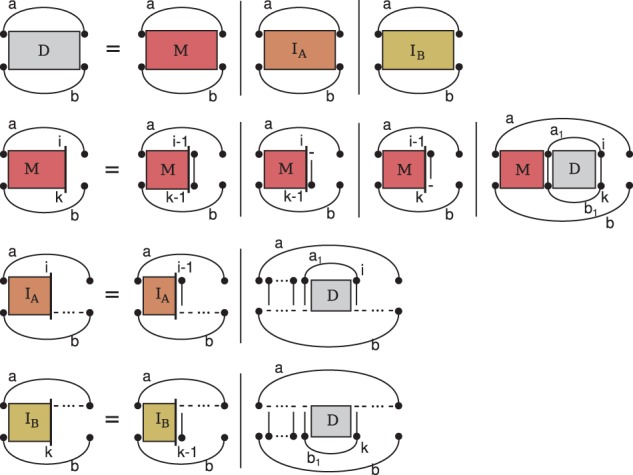

Alignment and folding with the original structure and alignment dependencies of Sankoff requires substantially different recursions. However, we keep the presentation as uniform as possible to our presentation of the PMcomp algorithm. Most obviously, the deletion and insertion of loops requires additional matrices ( and ). More subtly, but centrally, we change the definition of matrix entries for pairs of base pairs. Where the PMcomp algorithm defines as the score of a consensus structure and an alignment matching a and b, PARSE requires optimum scores of structure alignment triples of the subsequences between (and excluding) the ends of a and b without assuming the match of those base pairs; these scores are stored in entries D(a,b). We recursively define entries for all , i and k ; Figure 2 visualizes these recursions.

Fig. 2.

Recursions of the novel lightweight alignment algorithm PARSE

The [resp. ] matrix correspond to the new case of a loop insertion into A (resp. . The additional cases and matrices do not add to the time or space complexity over the PMcomp algorithm; in particular, the space and time for the and matrices is dominated by the M matrices. Therefore, analogous arguments let us conclude that, assuming LocARNA-style ensemble-based sparsification, the algorithm runs (like LocARNA) in quadratic space and quartic time.

Affine gap cost

We add the affine gap costs of the previous section without increasing the complexity; in parallel to distinguishing opening costs for base and loop gaps, we apply different gap penalties. First, similar to the algorithm of Gotoh (1982), we introduce matrices with entries and ; these contain best scores of structure alignment triples like the entries , however, constrain the alignments to delete and insert , respectively. Thus, we define

for deletion, define analogously for insertion, and replace the deletion and insertion cases of the M-recursion of PARSE by and , respectively. Second, we extend the recursions for and . We show the case of , since is analogous. It suffices to make explicit the case of recursing to , which extends an already open gap, and add loop gap opening penalty in the general case of recursing to .

Notably, these extensions do not change the time or space complexity.

3.3 SPARSE—folding and alignment of RNA with ensemble-based sparsification

This section describes the sparsification of PARSE, resulting in SPARSE, which achieves quadratic time complexity. Instead of filling the whole matrix Mab for each pair of base pairs a, b, we are going to skip matrix cells that do not contribute to probable solutions. To define the probable structures and alignments, and thus determine the ‘relevant’ entries of the matrix, we define several probabilities of structure elements in the structure ensemble of a sequence A. For defining these probabilities, we assume that the structures of an RNA sequence A are Boltzmann-distributed in the structure ensemble, where RNA energy is given by a loop-based energy model.

denotes the probability that a structure in the ensemble of A contains the base pair (i, j).

, denotes the joint probability that for a structure in the ensemble of A, (i, j) is a base pair of or the pseudo base pair and k is unpaired in the loop closed by (i, j).

, denotes the joint probability that for a structure in the ensemble of A, (i, j) is base pair of or the pseudo base pair and the ends of are in the loop closed by (i, j).

Note that we explicitly include the case that (i, j) is the pseudo base pair , which closes the external loop. The base pair probabilities are the immediate outcome of McCaskill’s original algorithm (McCaskill, 1990), whereas we calculate the joint probabilities by an extension of this algorithm with the same computational complexity (Otto et al., 2014). Importantly for the complexity of our final algorithm, all these probabilities can be precomputed since they depend only on the single sequences.

3.3.1 Sparse structure and alignment space

The key to sparsifying PARSE, is to optimize only over a subset of solutions, namely probable structures and alignments defined applying fixed probability thresholds θ1, θ2 and θ3 to the above probabilities.

Definition 2 —

(Sparse Structure and Alignment Space). Assume fixed thresholds and sequences A and B. The structure alignment triple of A and B is contained in the sparse structure and alignment space of A and B and, for this reason, called sparse iff

and for all base pairs and and for all , i unpaired and internal in , k unpaired and internal in , where denotes the parent of i in and , the parent of k in and for all internal base pairs a in S and b in T, where denotes the parent of a in S; , the parent of b in T.

Note that in those definitions, explicitly we do not restrict elements in the external loop by Conditions (C2) and (C3), since this does not improve the final complexity further (see Complexity Analysis), but allows more flexibility. An alternative, which we have chosen in our implementation, is filtering the external bases and base pairs by their probabilities to be external (i.e. treating them as elements of the external loops and ).

Finding the best structure alignment triple in the sparse space is a form of constrained evaluation of the PARSE recursions (see previous section). We modify the recursions such that only cases are considered that extend a sub-solution in a way that satisfies the conditions of Definition 2. First of all, only matrices for base pairs a and b satisfying Condition (C1) are considered. This restricts the cases of the recursions for M, and that predict base pairs (in , or both.) Furthermore, Condition (C2) constrains the base match case of the M-recursion; and Condition (C3), its base pair match case.

Constraining the recursion cases based on these probabilities is possible only because, during the evaluation, one has determined the base pairs closing the loop containing the considered bases and base pairs in the single structures. In contrast, previous PMcomp-like algorithms, e.g. LocARNA (Will et al., 2007), RAF (Do et al., 2008) and FoldAlignM (Torarinsson et al., 2007), keep track of only the consensus structure (i.e. the pairs of base pairs matched to each other). Thus, one cannot apply the appropriate joint probabilities with respect to closing base pairs in the single structures; consequently, the developed techniques are not applicable. Figure 3A illustrates that constraining according to loops in the consensus structure would discard relevant structure alignment triples. In the figure, the base pair a3 is highly unlikely contained in the loop closed by a1 (due to stacking, it is much more likely in the loop closed by a2.) Consequently, even moderate thresholds would disallow its alignment to b2.

Fig. 3.

(A) Example alignment. Due to stacking effects, the probability of a base pair a3 in the loop closed by a2 (loop of single structure) is much higher than its probability in the loop closed by a1 [loop of the consensus structure ]. (B) Computing represented entries in the sparsified algorithm. We show the matrix Mab; the rounded bars left and on top of the matrix symbolize the represented positions for a and b; the gray areas contain the represented entries for Mab. In our example, the entry recurses (solid arrows) to unrepresented entries , and (white boxes); the latter via matching base pairs; their left ends correspond to the dashed box at . The numbers 1-4 at the arrow heads refer to the respective recursion case. The unrepresented entries are computed from represented entries (dashed arrows to black boxes), each in constant time

3.3.2 Sparsified evaluation

Constraining the evaluation allows us to represent and fill the matrices only partially for optimizing in the sparse structure and alignment space. Concretely, we do not represent all matrix entries that can be derived only via insertion and deletion cases, since we calculate them from smaller represented entries by adding appropriate gap cost (Fig. 3B).

Definition 3 —

(Represented entries). A position i in A is represented for a base pair (), iff or there exists some (): and . The position is called predecessor of i for a. The entry is represented iff i is represented for a; , iff k is represented for b; and , iff both conditions hold.

Lemma 1 —

(Value of unrepresented entries). Restricting the optimization to the sparse alignment and structure space, an unrepresented entry has the value , where is the predecessor of i for a and is the predecessor of k for b.

Intuitively, Lemma 1 holds, since the unrepresented entries in a matrix Mab correspond to alignments of subsequences and that must end in a gap (because the base match (i, k) and the match of base pairs with right ends i and k are disallowed). Moreover, in such an alignment the entire subsequences and cannot be aligned. The formal proof of Lemma 1 is given in the appendix.

3.3.3 Complexity analysis

Let us prepare the analysis of SPARSE by first deriving the time complexity of PMcomp, where we apply the weak ensemble-based sparsification of LocARNA, i.e. and contain only base pairs satisfying Condition (C1) of Definition 2. Then, for each position i of A, the number of base pairs where is constantly bounded by ; analogously, this holds for (Will et al., 2007). Consequently, evaluating each single entry takes constant time; it remains to count the computed entries. Define the number of times each respective position i (or k) in sequence A (or B) is considered in combination with some base of the second sequence in the entire computation. Denote this number of times by . Then, we count the computed entries by Because, and , we have re-derived the time complexity .

Theorem 1 —

SPARSE optimizes the folding and alignment score in the sparse structure and alignment space in O(nm) time and space.

PROOF —

Analogous to the above analysis of PMcomp, we bound the time complexity in the same way from numbers and , where is the number of base pairs a in such that i is represented for a. The sum over all such base pairs a of the terms is smaller or qual 1, since this is a sum of probabilities of disjoint events. Due to the Conditions (C2) and (C3), each term is at least , which bounds the number of such base pairs a, i.e. , by in O(1). Finally, the complexity is bounded by for computing all entries and filling in O(nm).

3.3.4 Relaxing the problem for further speedup

So far, we have considered finding the best sparse structure alignment triple. In practice, it is usually sufficient to find some (not necessarily sparse) triple that is at least as good as any sparse triple. For solving the relaxed problem, analogously to the optimization of PMcomp, we combine the computation of all matrices , where and for and positions i and k. For all these matrices, we consider an entry iff it is a represented entry of any of the matrices. Consequently, each considered entry would have been considered by the first algorithm at least once, but possibly several times for different matrices . Although, thus, we do not increase the complexity, we save computation time in the latter case. This algorithm searches completely through all sparse structure alignment triples. However, it can not guarantee that the triple is sparse. For example, a solution could match a base that is not represented for a predicted base pair a1 (), but is represented for an (unpredicted) base pair a2 () that shares the left end with a1 ().

3.4 Multiple alignment

To construct multiple alignments, we suggest a progressive alignment pipeline based on the pairwise SPARSE algorithm. There, we apply SPARSE to construct the guide tree and to align profiles in each progressive step. Unlike PMmulti, the multiple alignment extension to PMcomp (Hofacker et al., 2004), which otherwise applies a similar strategy, we apply RNAalifold (Hofacker et al., 2002; Bernhart et al., 2008) to compute ‘profile’ consensus dot plots in the progressive phase.

For aligning k sequences with maximal length n, we start by computing pairwise alignments between all pairs of the input sequences. Because the required ensemble probabilities depend only on the single sequences, they are precomputed for each sequence. Thus, all pairwise alignments are performed in time. Then, the pipeline constructs a guide tree in time by UPGMA (Gronau and Moran, 2007). In each step of the progressive alignment, RNAalifold computes all required ensemble probabilities in and SPARSE calculates an alignment in (We extended RNAalifold to compute the additional joint probabilities without changing the complexity.). Thus, the progressive alignment takes time, resulting in total time . In comparison, the corresponding pipeline for LocARNA requires time.

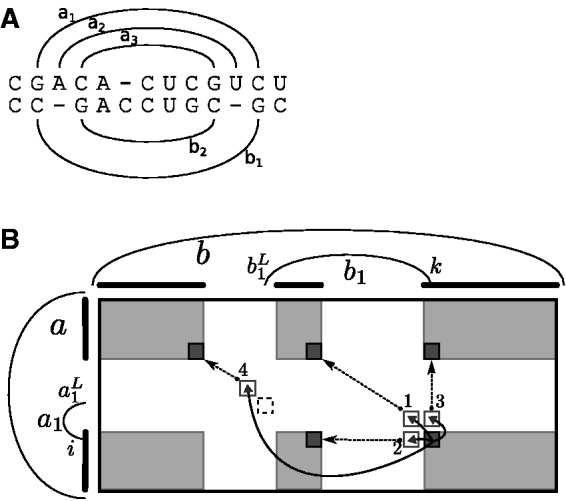

4 Results

4.1 Speedup and alignment quality

We evaluated our implementation of SPARSE on the Bralibase 2.1 (Wilm et al., 2006) benchmark sets k2 and k3, which consist of pairwise and three-way alignments, respectively. We compared SPARSE to LocARNA and RAF; For set k2, which contains only short and medium-sized RNAs of ∼110 nt average length, SPARSE and RAF achieve similar speed ups over LocARNA (Table 1) (For SPARSE, we used these values: θ1 = 1e-3, θ2 = 5e-5, θ3 = 1e-4, βbase = −900, γbase = −3500, βloop = −900 and γloop = −350; for LocARNA and RAF, we used default settings.). For each alignment tool, Figure 4 shows the dependency of alignment quality on sequence identity across k2; for each benchmark instance, the quality is measured as similarity to the Rfam-derived reference alignment reported as sum-of-pairs score (SPS) by compalignp (Wilm et al., 2006). The dependencies are estimated by non-parametric regression (lowess; Cleveland, 1981). This resulting curve visualizes the approximate average SPS at each sequence identity. To furthermore visualize the distribution of the SPS values, we iterated the lowess method both on the elements above and below of the main lowess curve. LocARNA and SPARSE show qualitatively similar performance; across the entire range of sequence identities, we observe a largely constant quality offset, where both tools maintain a high alignment quality even for low sequence identities. In contrast, the quality of RAF alignment drops dramatically when sequence similarity decreases; we conjecture that this is a consequence of the strong sequence-based heuristics in RAF. Our benchmarks on k3 (Supplementary Fig. S1) suggest that this behavior extends to multiple alignment. Although all RNA comparison tools introduce some form of time-quality trade-off, remarkably, in terms of alignment quality SPARSE and RAF behave strongly different at very similar run times.

Table 1.

Total run-time and speed up of pairwise alignments due to sparsification across Bralibase 2.1 set k2

| Tool | Total time (s) | Mean time (s) | Speedup (versus LocARNA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LocARNA | 13400 | 1.49 | 1.0 |

| SPARSE | 3600 | 0.40 | 3.7 |

| RAF | 3200 | 0.36 | 4.2 |

Fig. 4.

Alignment quality (measured by SPS) at different sequence identities for pairwise alignments (Bralibase 2.1 set k2). The curves are lowess curves (Cleveland, 1981) through data points for each benchmark instance. The thin lines visualize the distribution of scores by estimating the respective instance averages above and below of the main lowess curve

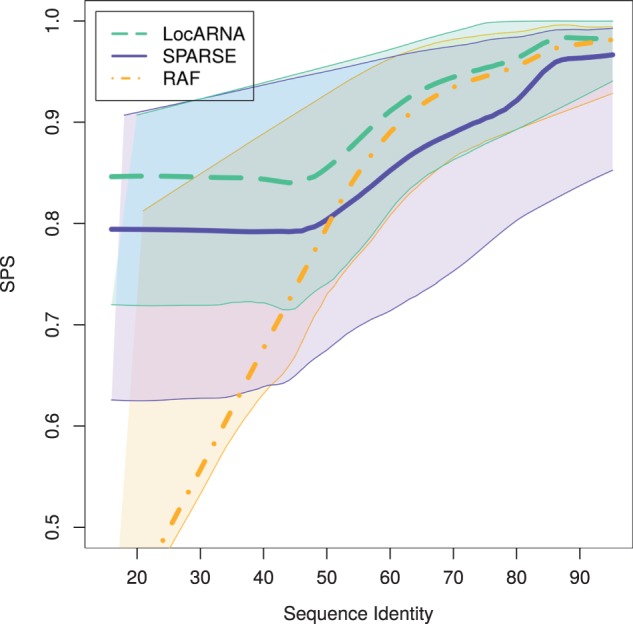

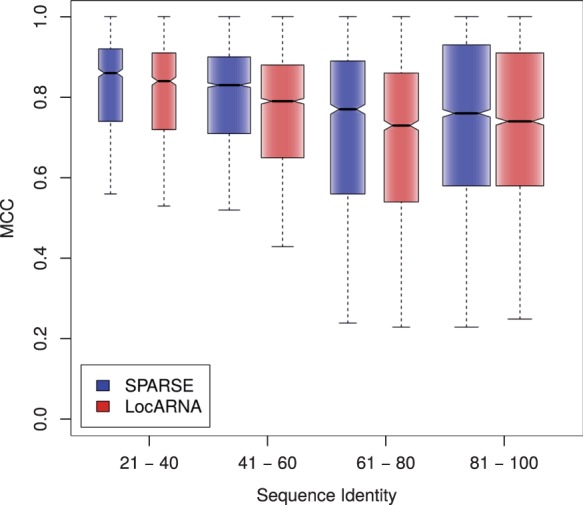

4.2 The SPARSE model improves folding

Moreover, we studied the effect of the novelties in the SPARSE alignment model. Recall that only SPARSE maintains the full flexibility of Sankoff’s approach in the lightweight model, while all previous methods restrict Sankoff’s model by disallowing loop insertions and deletions. Furthermore, the sparsification of SPARSE is expected to affect structure prediction (cf. Fig. 3A.) Comparing our implementations of SPARSE and LocARNA enables isolating these effects, since by design these implementations behave as similar as possible otherwise. The quality of each predicted structure is measured as Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC; Matthews, 1975) relative to the Rfam-derived reference structure. For each sequence of the benchmark, we derive reference structures from Rfam, by constrained folding of the associated Rfam consensus structure of the sequence. We compute MCC values for predictions by SPARSE and LocARNA across k2. Figure 5 compares the structure prediction quality by SPARSE and LocARNA. Visualized by the non-overlapping notches, there is strong evidence for improvements (Chambers et al., 1983) across all sequence identity ranges covered by the benchmark set. For example, these effects are illustrated well by RNAs of the family gcvT (Appendix).

Fig. 5.

Structure prediction quality measured by MCC within different ranges of average pairwise sequence identity (APSI) shown as boxplots. (Bralibase 2.1 set k2) whiskers are extended up to one interquartile range from the boxes

Although SPARSE improved prediction quality and speed over LocARNA, these results suggest even more general conclusions. That is, the improvements can be directly ascribed to the single differences of the tools: sparsification and model flexibility.

5 Discussion

We presented a novel method for simultaneous alignment and folding of RNAs. The relevance of this method is 2-fold. First, we developed the first full-featured lightweight variant of the Sankoff model. This fundamentally improves over the lightweight model of PMcomp. Because this model drastically lowered the computational burden of simultaneous alignment and folding, it has been adopted by many successful RNA alignment approaches. However, all of these methods lack the full flexibility of the Sankoff model; for the first time, SPARSE combines this flexibility with lightweight computation. Second, we present a novel method to speed up Sankoff-style alignment that is purely based on the structure ensemble of RNAs; in particular, it does not have to resort to sequence-based heuristics, which could compromise the alignment quality. We showed that by sparsification based on ensemble probabilities of unpaired bases and base pairs in specific loops, simultaneous alignment and folding requires only quadratic time.

Performing Bralibase 2.1 benchmarks, we demonstrated that, also in practice, the method provides a profound speed up. At similar speed as one of the fastest known simultaneous alignment and folding tools RAF, SPARSE maintains high alignment and folding quality for the ‘twilight’ zone of RNAs with low sequence identity, which are particularly hard to align. Finally, these benchmarks (and concrete examples, see Appendix) suggest that the added expressivity of the novel lightweight model improves the folding accuracy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Niklas Meinzer for implementing a benchmark tool for our evaluation and the anonymous reviewers for their help to improve this article.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG grants BA 2168/3-3, BA 2168/4-3 SPP 1395 InKoMBio, MO 2402/1-1) and German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF grant 031 6165A e:Bio RNAsys) to R.B.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Bernhart S.H., et al. (2008) RNAalifold: improved consensus structure prediction for RNA alignments. BMC Bioinformatics, 9, 474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers J.M., et al. (1983) Graphical Methods for Data Analysis . Wadsworth, Belmont, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Clark M.B., et al. (2011) The reality of pervasive transcription. PLoS Biol, 9, e1000625; discussion e1001102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland W.S. (1981) Lowess: a program for smoothing scatterplots by robust locally weighted regression. Am. Stat., 35, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Do C.B., et al. (2008) A max-margin model for efficient simultaneous alignment and folding of RNA sequences. Bioinformatics, 24, i68–i76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell R.D., Eddy S.R. (2006) Efficient pairwise RNA structure prediction and alignment using sequence alignment constraints. BMC Bioinformatics, 7, 400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner P.P., et al. (2005) A benchmark of multiple sequence alignment programs upon structural RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res., 33, 2433–2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh O. (1982) An improved algorithm for matching biological sequences. J. Mol. Biol., 162, 705–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronau I., Moran S. (2007) Optimal implementations of UPGMA and other common clustering algorithms. Inf. Process. Lett., 104, 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Harmanci A.O., et al. (2007) Efficient pairwise RNA structure prediction using probabilistic alignment constraints in Dynalign. BMC Bioinformatics, 8, 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofacker I.L., et al. (2002) Secondary structure prediction for aligned RNA sequences. J. Mol. Biol., 319, 1059–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofacker I.L., et al. (2004) Alignment of RNA base pairing probability matrices. Bioinformatics, 20, 2222–2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes I. (2005) Accelerated probabilistic inference of RNA structure evolution. BMC Bioinformatics, 6, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquier A. (2009) The complex eukaryotic transcriptome: unexpected pervasive transcription and novel small RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet., 10, 833–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews D., et al. (1999) Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol., 288, 911–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews B. (1975) Comparison of the predicted and observed secondary structure of t4 phage lysozyme. Biochem. Biophys. Acta, 405, 442–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaskill J.S. (1990) The equilibrium partition function and base pair binding probabilities for RNA secondary structure. Biopolymers, 29, 1105–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto C., et al. (2014) ExpaRNA-P: simultaneous exact pattern matching and folding of RNAs. BMC Bioinformatics, 15, 6602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker B.J., et al. (2011) New families of human regulatory RNA structures identified by comparative analysis of vertebrate genomes. Genome Res. 21, 1929–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rederstorff M., et al. (2010) RNPomics: defining the ncRNA transcriptome by cDNA library generation from ribonucleo-protein particles. Nucleic Acids Res., 38, e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y., et al. (2011) Fast and accurate clustering of noncoding RNAs using ensembles of sequence alignments and secondary structures. BMC Bioinformatics, 12 (Suppl 1), S48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankoff D. (1985) Simultaneous solution of the RNA folding, alignment and protosequence problems. SIAM J. Appl. Math., 45, 810–825. [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., et al. (2009) Metatranscriptomics reveals unique microbial small RNAs in the ocean’s water column. Nature, 459, 266–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorescu D.A., et al. (2012) CARNA—alignment of RNA structure ensembles. Nucleic Acids Res., 40, W49–W53. DAS, MMö, and MMa contributed equally to this work. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torarinsson E., et al. (2007) Multiple structural alignment and clustering of RNA sequences. Bioinformatics, 23, 926–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng H.-H., et al. (2009) Finding non-coding RNAs through genome-scale clustering. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol., 7, 373–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will S., et al. (2007) Inferring non-coding RNA families and classes by means of genome-scale structure-based clustering. PLoS Comput. Biol., 3, e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will S., et al. (2012) LocARNA-P: accurate boundary prediction and improved detection of structural RNAs. RNA, 18, 900–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilm A., et al. (2006) An enhanced RNA alignment benchmark for sequence alignment programs. Algorithms Mol. Biol., 1, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.