Abstract

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, the master mammalian circadian pacemaker, synchronizes endogenous rhythms with the external day-night cycle. Older humans, particularly those with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), often have difficulty maintaining normal circadian rhythms compared to younger adults, but the basis of this change is unknown. We report that the circadian rhythm amplitude of motor activity in both AD subjects and age-matched controls is correlated with the number of vasoactive intestinal peptide-expressing SCN neurons. AD was additionally associated with delayed circadian phase compared to cognitively healthy subjects, suggesting distinct pathologies and strategies for treating aging- and AD-related circadian disturbances.

Introduction

In mammals, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus acts as the master circadian pacemaker to drive and synchronize endogenous rhythms with the external day-night cycle. The SCN must provide a stable, strong circadian output while remaining adaptable to differences between endogenous and exogenous cycles that arise from seasonal changes in the time of sunrise and endogenous circadian periods not exactly equal to 24 hours in length. The SCN contains a core region composed mainly of neurons expressing vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and a shell region made up largely of arginine vasopressin (AVP)-expressing neurons1, which work in a complementary manner to impart stability and flexibility to the circadian timing system. The VIP neurons of the SCN core receive direct light input from the retina and provide intranuclear projections to the rest of the SCN. These neurons use the VPAC2 receptor2 to promote synchronicity of SCN neurons, which is important for maintaining a high-amplitude circadian output, and to allow photic resetting. The AVP neurons of the SCN are relatively resistant to photic phase shifting3, but provide extensive projections to SCN targets4.

In aged individuals, functional weakening of the circadian timing system and concomitant sleep impairments are associated with neurodegeneration and cognitive decline5. Compared to young adults, older humans have been reported to have fewer VIP-immunoreactive (-ir) and AVP-ir neurons in the SCN6,7. However, the relationship between the number of these SCN neurons and circadian activity rhythms in individual older community-dwelling adults is not known. To address this issue, we compared the numbers of surviving AVP-ir and VIP-ir neurons in the SCN with the actual circadian behavior of individual older adults, both with and without Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Materials and Methods

Human Subjects

We studied 17 individuals (mean age 90.4 years at death; 4 male) from the Rush Memory and Aging Project8 (MAP) who had at least 1 week of actigraphy within the 18 months prior to death. The MAP is a longitudinal, community-based study of the chronic conditions of aging, in which motor activity of subjects is monitored biennially for up to 10 days using actigraphs (Actical, Philips Respironics) placed on subjects’ non-dominant wrists (technical details of the actigraph recordings have been previously described9). A subset of subjects (n=7) had been diagnosed with AD, based on cognitive impairment and pathological confirmation, using the NINCDS-ADRDA and National Institute on Aging-Reagan Institute criteria, as described previously10.

The study was conducted in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Quantification of the Circadian Activity Rhythm

To estimate the circadian activity rhythm, we extracted the oscillatory component of ~24 hours in motor activity using the empirical mode decomposition algorithm with a masking procedure11 and normalized its amplitude to the standard deviation of the fluctuations at smaller time scales. This method measures 24 hour rhythmicity in locomotor activity, which is somewhat irregular, without making assumptions about the shape of the underlying waveform (e.g., a sine wave with the cosinor method or a square wave with the circadian index, see Chou et al.12). The software for the extraction of circadian activity rhythm is installed on the server of the Medical Biodynamics Program at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and will be available upon request.

Activity acrophases and nadirs were measured from the raw actigraphy records as the 8 consecutive hours with the most and least total activity each day, respectively. These times were then expressed in relation to sunrise time during the actigraphic recording to minimize the effect of seasonal changes in light-dark cycles on activity behavior between subjects. We also calculated a number of previously reported circadian measures, including circadian index (the peak-to-trough amplitude measured between the 8 hours of greatest and least activity, normalized to the total activity in the day)12, interdaily stability (a measure of how similar the actigraphic records are from day to day)13, and intradaily variability (a measure of the fragmentation of the activity rhythm)13.

Brain Tissue Processing and Immunohistochemistry

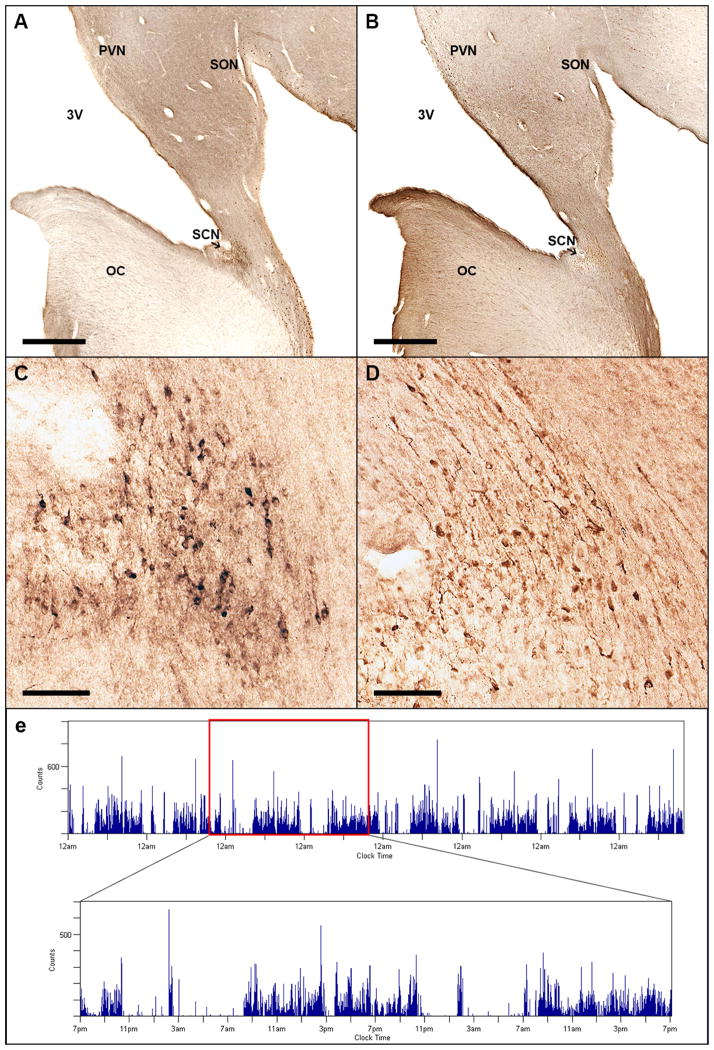

Upon death, we manually dissected blocks of tissue from these subjects containing the hypothalamus from the chiasmatic region to the mammillary bodies. The blocks were coronally sectioned into four 1:4, 50 μm series with one series immunohistochemically stained for VIP (anti-VIP, Immunostar, catalog# 20077, lot 1129001) and another stained for AVP (anti-AVP, Millipore, catalog# AB1565, lot LV1587742) (Fig. 1A–D). Preadsorption of either antibody with its target antigen prior to incubation of the tissue with the primary antibody completely abolished staining. We used methods identical to those recently described9.

Figure 1.

Representative anatomic and actigraphic data. Immunohistochemical staining of human suprachiasmatic nucleus for vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) (A, C) and arginine vasopressin (AVP) (B, D). Low power (a, b, scale bar = 1 mm) and high power views (c, d, scale bar = 100 μm) from a single subject in consecutive sections. (E) Visualization of actigraphy data from an illustrative participant. (Inset: detail view of 48 hours of this recording). OC = Optic Chiasm; PVN = Paraventricular Nucleus; SCN = Suprachiasmatic Nucleus; SON = Supraoptic Nucleus; 3V = 3rd ventricle.

As the VIP-ir and AVP-ir neurons are not always located at precisely overlapping rostral-caudal levels (i.e., one population may begin or end a section or two rostral to the other), we only quantified AVP- or VIP-ir neurons in brains where there was at least one section rostral and one section caudal to the stained neurons. Visual inspection of the stained sections determined that the blocks from 14 subjects contained the entire VIP-ergic SCN and the blocks from 14 subjects contained the entire AVP-ergic SCN (17 total subjects).

Stereological Cell Counts

Neuron counts of the SCN for each series were obtained using the optical fractionator stereological method, as previously described9. To avoid bias in assigning borders to the cell group, we counted all immunoreactive neurons in the region bounded ventrally by the optic chiasm, medially by the third ventricle, dorsally by the paraventricular nucleus, and laterally by the supraoptic nucleus. Photomicrographs presented in Figure 1 were prepared using Adobe Photoshop CS6. In order to show differences in distribution of the VIP-ir and AVP-ir neurons, minor adjustments to brightness and contrast were implemented to match the backgrounds of both photomicrographs, as the different antibodies used did not stain the tissue to the same darkness.

Statistics

We established that the data were normally distributed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Therefore, we compared cell counts and actigraphic measures between groups using Student’s t-test. To examine the relationship between number of SCN neurons and the amplitudes of the circadian rhythms, we used multivariate linear regressions. We applied the Bonferroni correction only to the principal analyses (number of SCN neurons and amplitude of circadian rhythms) and not to the exploratory analyses. All tests were two-tailed. To examine seasonal changes in VIP and AVP expression levels, we divided subjects into 4 seasons based on date of death; each season included the 90 days before and after its respective solar equinox or solstice. To examine diurnal changes in VIP and AVP expression levels, we divided subjects based on time of death into 4 groups: daytime (10:01–18:00), twilight (18:01–22:00), nighttime (22:01–06:00), and early morning (06:01–10:00).

Results

Clinical Characteristics

The 17 subjects with actigraphic recordings less than 18 months prior to death did not differ from the other subjects in the MAP by age, gender, race, years of education, body mass index, prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), or number of depressive symptoms, vascular risk factors, or vascular diseases (Table 1a). Subjects without AD were not different in age from subjects with AD (mean [SD] 90.5 [5.9] years at death vs. 90.1 [5.2], respectively). There were no significant differences in presence of comorbidities or in medication taken between subjects with and without AD (Table 1b).

Table 1a.

Demographic and clinical metrics of study participants

| Characteristic | Suprachiasmatic nucleus available and <18 months between actigraphy and death (n = 17) | Suprachiasmatic nucleus available and >18 months between actigraphy and death (n = 24) | Suprachiasmatic nucleus not available (n = 194) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| At time of actigraphy | 89.6 (5.5) [83.1 – 101.3] | 85.8 (7.5) [62.0 – 95.7] | 88.0 (6.2) [71.6 – 100.8] | 0.43 |

| At time of death | 90.4 (5.5) [83.9 – 101.6] | 88.5 (7.2) [65.9 – 97.8] | 89.5 (6.1) [72.7 – 102.7] | 0.97 |

| Female/Male sex | 13 (76.5%)/4 (23.5%) | 16 (66.7%)/8 (33.3%) | 133 (68.6%)/61 (31.4%) | 0.79 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 16 (94.1%) | 24 (100%) | 188 (96.9%) | |

| Black | 1 (5.8%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (2.6%) | 0.74 |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Education (years) | 14.1 (2.3) [10 – 18] | 14.3 (1.9) [12 – 18] | 14.7 (2.8) [8 – 25] | 0.98 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.0 (4.3) [17.9 – 33.7] | 28.5 (5.2) [20.9 – 40.8] | 26.0 (5.0) [17.0 – 41.2] | 0.09 |

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 8 (47.1%) | 10 (41.7%) | 70 (36.1%) | 0.60 |

| Number of depressive symptoms | 1.8 (1.9) [0 – 6] | 2.2 (2.6) [0 – 8] | 1.5 (2.0) [0 – 9] | 0.49 |

| Number of vascular risk factors | 1.4 (0.7) [0 – 2] | 1.1 (0.83) [0 – 3] | 1.3 (0.8) [0 – 3] | 0.62 |

| Number of vascular diseases | 0.53 (0.52) [0 – 1] | 0.61 (1.0) [0 – 4] | 0.77 (0.93) [0 – 4] | 0.39 |

| Self-reported hours of sleep | 7.5 (1.3) [5 – 10] | 7.2 (1.6) [5 – 11] | 7.4 (1.6) [4 – 12] | 0.99 |

All values expressed as Mean (Standard Deviation) [Range] or Number (Percentage). Continuous measures were tested across groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test; discrete measures tested using the chi-square test; and race and sex were tested using Fisher’s exact test.

Table 1b.

Comorbidities and medications of study subjects

| Metric | Non-AD (n = 10) | AD (n = 7) | Two-tailed t-test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-mortem interval | |||

| Mean (SD) [range] | 6.5 (2.2) [3.7 – 10] | 8.4 (4.3) [3.5 – 14.7] | 0.32 |

| Number of depressive symptoms | |||

| Mean (SD) [range] | 1.7 (2.1) [0 – 6] | 1.8 (1.7) [0 – 4]§ | 0.89 |

| Proportion of subjects with presence of: | |||

| Diabetes* | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.95 |

| Hypertension* | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.81 |

| Coronary artery disease* | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Peripheral vascular disease* | 0.20 | 0.43 | 0.37 |

| Stroke†‡ | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.34 |

| Congestive heart failure* | 0.13|| | 0.14 | 0.93 |

| Parkinson’s disease† | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Thyroid disease* | 0.20 | 0.43 | 0.37 |

| History of head injury resulting in loss of consciousness‡ | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.77 |

| Presence of medication for: | |||

| Depression | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.71 |

| Insomnia | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.18 |

| Psychosis | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.36 |

| Mania | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Neurological condition | 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.62 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.36 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.81 |

by self-report

by clinician physical exam

by clinician review of history

missing data from 1 subject

missing data from 2 subjects

Relationship of AVP-ir and VIP-ir Neurons in the SCN with Actigraphic Measures

The number of VIP-ir neurons in the SCN was highly positively correlated with the normalized amplitude of the 24-hour activity rhythm, when adjusted for age at death and sex (Fig. 2, multivariate linear regression, p=0.008, R=0.83). We did not find any other correlations between VIP or AVP neuron count and other rest-activity measures (circadian index12, interdaily stability13, intradaily variability13, time in rest, mean activity level, standard deviation of amplitude, and mean and standard deviation of period length, Table 2a). There was no diurnal or seasonal pattern in the number of VIP-ir or AVP-ir neurons based on time or season of death.

Figure 2.

Number of VIP-ir neurons in the SCN is associated with amplitude of the circadian rhythm of locomotor activity as assessed by actigraphy in subjects who died within 18 months of actigraphy (n = 14). Partial regression plot of model adjusted for age and sex. R indicates the partial correlation coefficient between the number of VIP-ir neurons and the amplitude of the circadian rhythm of locomotor activity. AD subjects plotted as triangles; non-AD subjects as circles.

Table 2a.

Associations between stereologic results and circadian actigraphy measures

| Metric | VIP (n = 14) | AVP (n = 14) | Adjusted for age at actigraphy and sex

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIP (n = 14) | AVP (n = 14) | |||||||||||

| Effect per 1000 cell change in VIP+ cells | SE | p- value | Effect per 1000 cell change in AVP+ cells | SE | p- value | Effect per 1000 cell change in VIP+ cells | SE | p- value | Effect per 1000 cell change in AVP+ cells | SE | p- value | |

| Circadian index | −0.27 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.70 | 0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.98 |

| IS | −0.001 | 0.02 | 0.99 | 0.008 | 0.01 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.79 |

| IV | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.25 | −0.006 | 0.02 | 0.81 | −0.007 | 0.04 | 0.89 | −0.0007 | 0.02 | 0.98 |

| Proportion of time in rest | −0.006 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.47 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.009 | 0.01 | 0.38 |

| Mean activity count/epoch | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.24 | −3.1 | 1.7 | 0.084 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 0.15 | −3.6 | 1.8 | 0.066 |

| Normalized Amplitude | 0.022 | 0.017 | 0.23 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.78 | 0.046 | 0.014 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.56 |

| SD of Norm. Amplitude | 5.2 | 2.7 | 0.073 | −2.1 | 1.4 | 0.17 | 7.5 | 3.3 | 0.044 | −2.4 | 1.5 | 0.13 |

| Period | −0.26 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.92 | −0.32 | 1.0 | 0.76 | −0.21 | 0.43 | 0.64 |

| SD of Period | −0.014 | 0.33 | 0.97 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.72 | −0.24 | 0.41 | 0.58 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.43 |

Statistically significant associations are listed in bold.

Circadian and Neuropathological Findings in Alzheimer’s Subjects

AD has been previously linked with reduced interdaily stability and fragmentation of the activity rhythm14, but diagnosis of AD did not significantly affect the normalized mean or standard deviation of circadian activity rhythm amplitude (t-tests, p=0.88, p=0.98, respectively, Table 2b). There was no significant difference in the number of SCN VIP-ir or AVP-ir neurons between non-AD and AD subjects (t-tests, p=0.13 and p=0.40, respectively, Table 2b). However, AD subjects were significantly phase delayed in comparison to non-AD subjects; on average, activity nadirs and acrophases occurred 2.9 hours later than in non-AD subjects, as defined by the midpoint of the 8-hour window with the least and greatest total activity each day, respectively (t-tests, p=0.048, p=0.0018, Table 2b).

Table 2b.

Effect of Alzheimer’s disease on circadian actigraphy measures

| Metric | Mean (SD) [range] | Two-tailed t-test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-AD (n = 10) | AD (n = 7) | ||

| Female/Male sex | 7 (70%)/3 (30%) | 6 (86%)/1 (14%) | |

| Circadian index | 1.267 (0.223) [0.990 – 1.63] | 1.199 (0.319) [0.921 – 1.86] | 0.62 |

| IS | 0.454 (0.129) [0.222 – 0.648] | 0.313 (0.083) [0.222 – 0.444] | 0.015 |

| IV | 1.57 (0.226) [1.26 – 1.97] | 1.66 (0.336) [1.18 – 2.04] | 0.54 |

| Proportion of time in rest | 0.678 (0.099) [0.447 – 0.787] | 0.733 (0.100) [0.614 – 0.834] | 0.28 |

| Mean activity count/epoch | 27.8 (20.8) [11.3 – 83.6] | 15.5 (12.4) [2.75 – 36.0] | 0.15 |

| Acrophase (hours, relative to sunrise) | +6.89 (1.94) [+3.83 – +9.18] | +9.83 (1.25) [+7.69 – +11.29] | 0.0018 |

| Females | +6.72 (2.16) [+3.83 – +9.18] | +9.87 (1.37) [+7.69 – +11.29] | 0.0095 |

| Males | +7.28 (1.62) [+5.58 – +8.81] | +9.61 | |

| Nadir (hours, relative to sunrise) | −2.70 (2.99) [−5.82 – 5.09] | +0.243 (2.59) [−2.93 – +4.88] | 0.048 |

| Females | −2.39 (3.60) [−5.82 – 5.09] | −0.530 (1.74) [−2.93 – +1.64] | 0.26 |

| Males | −3.43 (0.48) [−3.91 – −2.95] | +4.88 | |

| Normalized Amplitude | 0.192 (0.113) [0.039 – 0.391] | 0.201 (0.134) [0.081 – 0.484] | 0.88 |

| SD of Norm. Amplitude | 21.8 (18.0) [6.20 – 66.7] | 22.1 (28.8) [2.49 – 84.6] | 0.98 |

| Period | 24.2 (6.41) [17.5 – 41.2] | 23.5 (4.15) [16.7 – 30.8] | 0.78 |

| SD of Period | 3.19 (2.23) [1.03 – 6.77] | 3.10 (2.26) [0.00 – 6.35] | 0.93 |

Statistically significant associations are listed in bold.

Discussion

These observations are compatible with the hypothesis that VIP-ergic neurons in the SCN are important for the ability to maintain high-amplitude circadian rhythms of activity. The retinorecipient VIP neurons receive direct retinal light input to maintain synchronicity between endogenous rhythms and the external light-dark cycle. Loss of these neurons would result in a decreased ability to entrain to light cues and to maintain synchronized internal SCN rhythms, leading to reduced circadian outputs from the SCN. Thus, diminished amplitudes of circadian rhythms in older people may be due to loss of VIP-ergic neurons in the SCN, consistent with previous observations that the amplitude of circadian body temperature rhythms declines with aging15. Decreased circadian amplitude can behaviorally manifest both in lower activity levels during the day and in greater nighttime movement and awakenings.

Other studies have reported loss of AVP neurons in the SCN with AD, and concomitant fragmentation of activity records. We did not observe these changes in our subjects, perhaps due to different methods used to quantify neurons between these studies. For example, Harper et al.16 reported that loss of AVP-ir neurons in the SCN correlated with activity fragmentation. However, they calculated ratios of AVP-ir neuronal profiles to glial cell profiles in a few selected cell fields in the SCN, rather than total numbers of AVP-ir neurons throughout the nucleus. We used a stereologically rigorous method that quantifies all stained neurons in the nucleus.

Liu and colleagues17 reported lower levels of AVP mRNA expression in the SCN of subjects with AD. However, they were not able to quantify the numbers of AVP mRNA-containing neurons, and in a previous study7 the same group had reported no change in the numbers of AVP-ir neurons in the SCN of elderly subjects (81–100 years old) with dementia compared to those who were not demented. We could not measure mRNA levels in our tissue because it was prepared in a way that did not block the effects of RNAses. However, the amount of AVP protein per cell (which is visualized by immunohistochemistry) may be different from the mRNA levels, and in our series, there was no difference in the number of AVP-ir neurons in the AD compared to the non-AD groups, and no correlation with any measure of circadian activity. While it is possible that some SCN neurons may have had AVP or VIP levels that were below the threshold for detection with our methods, this situation would have applied equally across all of our cases. In addition, even if neurons that had levels of these peptides below our threshold were “dormant” rather than lost, the implication for the circadian correlates would be the same. On the other hand, the absence of correlation of numbers of AVP-ir neurons with circadian rhythms of activity does not necessarily mean that they cannot play a role, just that this would have to be due to alterations of activity, rather than neuron number.

The AD subjects had normalized circadian amplitudes of activity that were similar to the non-AD subjects but showed a consistent phase delay in their activity rhythms of ~3 hours, similar to that reported in body temperature rhythms15. This phase delay may result in sundowning: evening agitation, confusion, and wandering after family members have fallen asleep for the night, which is a frequent cause of institutionalization18. On the other hand, the phase delay in these AD subjects is apparently not related to damage to the principal neuron types in the SCN, and therefore is may reflect deranged inputs to the SCN. For example, AD patients suffer loss of serotonergic neurons in the median raphe nucleus19, which heavily innervates the SCN and modulates its photic resetting20.

Our findings suggest that exposure to bright morning light is likely to drive the remaining VIP neurons and may be the basis of previously reported21,22 positive responses to morning bright light therapy in AD subjects. As the principal cell types of the SCN apparently are not damaged by AD, photic or pharmacological treatment directed at restoring appropriate circadian phase may help avoid institutionalization of AD patients.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Veronique van der Horst, Dr. Glenn Rosen, and Mr. Brian Ellison for technical advice and assistance, as well as the staff of the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, and most of all the participants of the Rush Memory and Aging Project and their families, without whom this study would not have been possible. This work was supported by a Dana Foundation Clinical Neuroscience Grant, Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan and National Science Council of Taiwan grants NSC 102-2911-I-008-001, NSC 102-2221-E-008-008, and NSC 103-2221-E-008-006-MY3, Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan support for the Center for Dynamical Biomarkers and Translational Medicine, CGH-NCU Joint Research Foundation grants CNJRF-101CGH-NCU-A4 and VGHUST103-G1-3-3, U.S. National Institutes of Health grants P01AG009975, P01HL095491, R00HL102241, R01NS072337, R01AG017917, R01AG024480, R01NS078009, R01AG043379, and R01AG042210, Canadian Institutes of Health Research grants MOP125934 and MMC132692, the Illinois Department of Public Health, and the Robert C. Borwell Endowment Fund.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Saper CB. The central circadian timing system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23(5):747–51. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An S, Harang R, Meeker K, et al. A neuropeptide speeds circadian entrainment by reducing intercellular synchrony. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(46):E4355–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307088110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaguchi Y, Suzuki T, Mizoro Y, et al. Mice genetically deficient in vasopressin V1a and V1b receptors are resistant to jet lag. Science. 2013;342(6154):85–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1238599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrahamson EE, Moore RY. Suprachiasmatic nucleus in the mouse: retinal innervation, intrinsic organization and efferent projections. Brain Res. 2001;916(1–2):172–91. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02890-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondratova AA, Kondratov RV. The circadian clock and pathology of the ageing brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(5):325–35. doi: 10.1038/nrn3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou J-N, Hofman MA, Swaab DF. VIP neurons in the human SCN in relation to sex, age, and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16(4):571–576. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00043-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swaab DFF, Fliers E, Partiman TSS. The suprachiasmatic nucleus of the human brain in relation to sex, age and senile dementia. Brain Res. 1985;342(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, et al. Overview and findings from the rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9(6):646–63. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim ASP, Ellison BA, Wang JL, et al. Sleep is related to neuron numbers in the ventrolateral preoptic/intermediate nucleus in older adults with and without Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 10):2847–61. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, et al. Neuropathology of older persons without cognitive impairment from two community-based studies. Neurology. 2006;66(12):1837–44. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219668.47116.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senroy N, Suryanarayanan S, Ribeiro PF. An Improved Hilbert–Huang Method for Analysis of Time-Varying Waveforms in Power Quality. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2007;22(4):1843–1850. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou TC, Scammell TE, Gooley JJ, et al. Critical Role of Dorsomedial Hypothalamic Nucleus in a Wide Range of Behavioral Circadian Rhythms. J Neurosci. 2003;23(33):10691–10702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10691.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sokolove PG, Bushell WN. The chi square periodogram: its utility for analysis of circadian rhythms. J Theor Biol. 1978;72(1):131–60. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(78)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatfield CF, Herbert J, van Someren EJW, et al. Disrupted daily activity/rest cycles in relation to daily cortisol rhythms of home-dwelling patients with early Alzheimer’s dementia. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 5):1061–74. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harper DG, Volicer L, Stopa EG, et al. Disturbance of endogenous circadian rhythm in aging and Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(5):359–68. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.5.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harper DG, Stopa EG, Kuo-Leblanc V, et al. Dorsomedial SCN neuronal subpopulations subserve different functions in human dementia. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 6):1609–17. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu RY, Zhou JN, Hoogendijk WJ, et al. Decreased vasopressin gene expression in the biological clock of Alzheimer disease patients with and without depression. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59(4):314–22. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.4.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollak CP, Perlick D. Sleep Problems and Institutionalization of the Elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1991;4(4):204–210. doi: 10.1177/089198879100400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen CP, Eastwood SL, Hope T, et al. Immunocytochemical study of the dorsal and median raphe nuclei in patients with Alzheimer’s disease prospectively assessed for behavioural changes. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2000;26(4):347–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2000.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morin LP. Serotonin and the regulation of mammalian circadian rhythmicity. Ann Med. 1999;31(1):12–33. doi: 10.3109/07853899909019259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satlin A, Volicer L, Ross V, et al. Bright light treatment of behavioral and sleep disturbances in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(8):1028–32. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.8.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovell BB, Ancoli-Israel S, Gevirtz R. Effect of bright light treatment on agitated behavior in institutionalized elderly subjects. Psychiatry Res. 1995;57(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02550-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]