Abstract

Rationale

5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) transport inhibitors can attenuate the abuse-related effects of cocaine and the mechanisms underlying this attenuation may involve activation of 5-HT2C receptors.

Objectives

We investigated the consequences of direct and indirect pharmacological activation of 5-HT2C receptors on reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior induced by cocaine priming and a cocaine paired stimulus.

Methods

Monkeys were trained to self-administer cocaine under a second-order schedule in which responding was maintained by i.v. cocaine injections and a cocaine-paired stimulus. Drug seeking was extinguished by replacing cocaine with vehicle and eliminating the cocaine-paired stimulus. During reinstatement tests, animals received a priming injection of cocaine along with restoration of the cocaine-paired stimulus, but only vehicle was available for self-administration.

Results

Pretreatment with either the 5-HT transport inhibitor fluoxetine (5.6 mg/kg) or the 5-HT2C receptor agonist Ro 60-0175 (1 mg/kg) attenuated reinstatement of drug seeking by cocaine priming. The reinstatement-attenuating effects of both drugs were reversed by the 5-HT2C receptor antagonist SB 242084 (0.03–0.56 mg/kg). Ro 60-0175 (1 mg/kg) attenuated cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking regardless of whether priming injections were or were not accompanied by restoration of the cocaine-paired stimulus. Ro 60-0175 (0.56 mg/kg) was equally effective whether it was administered acutely or chronically. Finally, Ro 60-0175 (0.3–1 mg/kg) had observable behavioral effects suggestive of anxiolytic-like properties.

Conclusions

5-HT2C receptor mechanisms play a key role in the modulation of cocaine-induced reinstatement by fluoxetine and Ro 60-0175. Direct activation of 5-HT2C receptors may offer a novel, tolerance-free therapeutic strategy for prevention of cocaine relapse.

Keywords: Cocaine, Serotonin, Reinstatement, Monkey

Previous preclinical studies have shown that pharmacological inhibition of serotonin (5-HT) uptake resulting in increased levels of 5-HT in the synapse can attenuate the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine, blunt cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking, and reduce cocaine-induced increases in striatal extracellular dopamine (Spealman 1993; Howell and Byrd 1995; Czoty et al. 2002; Rüedi-Bettschen et al. 2010; Sawyer et al. 2012). However, the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the cocaine-attenuating effects of 5-HT uptake inhibition have not been established fully.

The actions of 5-HT are mediated through at least 16 receptor subtypes grouped into seven families (5-HT1R – 5-HT7R) according to their structural and functional characteristics (for review see Bubar and Cunningham 2008). Molecular/genetic and pharmacological studies have implicated several 5-HT receptor subtypes in the behavioral effects of fluoxetine, citalopram and other 5-HT transport inhibitors. For example, the anti-depressive action produced by chronic fluoxetine administration has been attributed to changes in the level of mRNA or receptor protein, as well as to alterations in downstream signaling, associated with the 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor subtypes (Brink et al. 2004; Barbon et al. 2011; Li et al. 2012). 5-HT2B receptors also appear to be involved in the anti-depressant actions of 5-HT transport inhibitors, as the effects of fluoxetine and paroxetine were abolished in 5-HT2B receptor knockout mice compared to wild type mice in a novelty-suppressed feeding (Diaz et al. 2012).

Only a few studies have investigated the 5-HT receptor mechanisms underlying the cocaine-modulating effects of 5-HT transport inhibitors. Rüedi-Bettschen et al. (2010) found evidence of a role for 5-HT1A receptors, showing that fluoxetine-induced attenuation of cocaine priming-induced reinstatement of drug seeking could be reversed with the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT. Additionally, Sawyer et al. (2012) showed that concomitant with fluoxetine-induced attenuation of cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking and cocaine-elicited dopamine overflow, there was evidence of fluoxetine-induced desensitization of the 5-HT2A receptor.

Recently, evidence has emerged that stimulation of 5-HT2C receptors with selective agonists can attenuate cocaine-induced elevations of dopamine within the nucleus accumbens in both rodents and monkeys, mimicking the effects of 5-HT transport inhibitors (Navailles et al. 2008; Manvich et al. 2012a). In rodents, 5-HT2C receptor agonists also have been shown to block several cocaine-induced behavioral effects including hyperlocomotion (Grottick et al. 2000; Filip et al. 2004; Fletcher et al. 2004; Craige and Unterwald 2013), discriminative stimulus effects (Frankel and Cunningham 2004), self-administration (Grottick et al. 2000; Fletcher et al. 2004; 2008) and reinstatement of drug seeking (Grottick et al. 2000; Neisewander and Acosta 2007). Likewise, in monkeys, the 5-HT2C receptor agonists mCPP and Ro 60-0175 have been reported to reduce the behavioral stimulant, reinforcing and relapse-inducing effects of cocaine (Manvich et al. 2012a). Given the striking overlap in the neurochemical and behavioral effects of 5-HT2C receptor agonists compared to 5-HT transport inhibitors, as well as the fact that 5-HT2C receptors are distributed in key mesolimbic dopamine circuits (Lopez-Gimenez et al. 2001; Bubar and Cunningham 2007), it is reasonable to investigate the contribution of this receptor subtype to the behavioral effects of 5-HT transport inhibitors.

To understand the contribution of 5-HT2C receptors to the behavioral effects 5-HT transport inhibitors, it is first necessary to understand the role of these receptors themselves in the behavioral effects of cocaine. Therefore, we systematically evaluated the ability of the selective 5-HT2C receptor agonist Ro 60-0175 and the selective 5-HT2C antagonist SB 242084 to modulate cocaine priming-induced reinstatement of drug seeking using a nonhuman primate model of cocaine relapse (e.g., Spealman et al. 1999). Because Ro 60-0175 has been shown to block reinstatement of drug seeking induced by contextual cues (e.g., Burbassi and Cervo 2008; Fletcher et al. 2008), we also compared the extent to which Ro 60-0175 attenuated cocaine priming-induced reinstatement in the presence and absence of response-contingent presentations of a cocaine-paired stimulus. Additionally, because tolerance has been shown to develop rapidly with some 5-HT drugs including 5-HT2C receptor agonists (e.g., Fone et al. 1998), we evaluated the effects of Ro 60-0175 on cocaine priming-induced reinstatement of drug seeking after both acute and chronic administration. We also characterized the role of 5-HT2C receptors in fluoxetine-induced attenuation of cocaine-induced priming with the selective 5-HT2C antagonist SB 242084. Lastly, we evaluated the effects of Ro 60-0175 in observational studies to determine the extent to which any observed attenuation was specific to cocaine or the result of more general behavioral disruption.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and surgical procedure

Ten adult squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus), weighing 700 to 1000 g, were studied in daily experimental sessions (Monday to Friday). Between sessions, monkeys lived in individual home cages in a climate-controlled vivarium where they had unlimited access to water and received a nutritionally balanced diet (Teklad Monkey Diet, supplemented with fresh fruit). All monkeys were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee on Animals of the Harvard Medical School and the “Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”, 8th edition of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, Department of Health, Education and Welfare Publication No. (NIH) 85-23, revised 2011. Research protocols were approved by the Harvard Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Before beginning the present study, monkeys were prepared with a chronic indwelling venous catheter (polyvinyl chloride, inside diameter: 0.015 mm; outside diameter: 0.035 mm) using the surgical procedures described by Platt et al. (2012). Briefly, under isoflurane anesthesia and aseptic conditions, one end of a catheter was passed to the level of the right atrium by way of a femoral or jugular vein. The distal end of the catheter was passed subcutaneously and exited in the mid-scapular region. Catheters were flushed daily with saline and were sealed with stainless steel obturators when not in use. Monkeys wore nylon-mesh jackets (Lomir Biomedical; Toronto, Canada) at all times to protect the catheter.

Apparatus

Experimental sessions were conducted in ventilated and sound-attenuating chambers that were equipped with white noise generators to mask external sounds. Within the chamber, monkeys were seated in primate chairs with a response lever mounted on the front panel (Med Associates, Inc.; Georgia, VT). Each press of the lever with a minimum downward force of approximately 0.25 N was recorded as a response. Colored lights mounted above the lever could be illuminated to serve as visual stimuli. Catheters were connected to a syringe pump (Med Associates, Inc.; Georgia, VT) located outside of the chamber. Each operation of the pump lasted 1 s and delivered 0.18 ml of vehicle or drug solution into the catheter.

Cocaine self-administration and extinction

Monkeys were trained to self-administer cocaine under a second-order fixed-interval (FI), fixed-ratio (FR) schedule of i.v. drug injection similar to the schedule described by Khroyan et al. (2000). Briefly, in the presence of a white light, completion of every 10th or 30th response (FR10 or FR30, depending on the particular monkey) during a 10 min FI resulted in a 2 s presentation of a red light. Completion of the first FR after the FI elapsed resulted in an i.v. injection of cocaine simultaneous with the onset of the red light (cocaine-paired stimulus). Each injection was followed by a 60 s time out (TO) period, during which all lights were off and responses had no scheduled consequences. If the FR requirement was not completed within 8 min following the expiration of the FI, the component ended automatically without an injection and was followed by a 60 s TO period. Daily sessions ended after completion of five cycles of the second-order schedule or a maximum of 90 min, whichever occurred first. Initially, the dose of cocaine was varied over a 10-fold or greater range to determine the dose that maintained maximum rates of responding for each monkey. The selected cocaine doses were 0.3 (N = 3), 0.18 (N = 4) or 0.1 mg/kg/infusion (N = 3) depending upon the monkey, and these doses of cocaine were kept constant for the remainder of the study.

After establishment of stable cocaine self-administration over a period of 6 to 8 months, responding was extinguished by substituting saline for cocaine as the available solution for self-administration and omitting presentations of the cocaine-paired stimulus. Extinction sessions, including session and TO durations, were otherwise identical to those described above. Extinction sessions were conducted daily until responding declined and stabilized at ≤10% of the response rate maintained during active cocaine self-administration for at least 2 consecutive sessions.

Reinstatement of drug seeking

Tests for priming-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine seeking were begun once the criteria for extinction were satisfied. Reinstatement test sessions used procedures identical to those during cocaine self-administration except that only saline was available for self-administration. Response-contingent presentations of the cocaine-paired stimulus were restored during reinstatement test sessions because earlier studies showed that reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior was greatest when cocaine priming was accompanied by restoration of the cocaine-paired stimulus (Spealman et al. 2004). Priming injections of cocaine and saline were administered i.v. immediately before the session. Between reinstatement test sessions, one or more extinction sessions were conducted to ensure that monkeys continue to meet the extinction criteria. Between experiments with different pretreatment drugs (described below), cocaine self-administration was re-established using the procedures described previously until responding stabilized (i.e., no systematic upward or downward trend in response rate over ≥ 3 consecutive sessions).

To evaluate the degree to which drug seeking was reinstated by a meaningful range of priming doses of cocaine, tests were conducted with saline and cocaine doses of 0.1 – 1 mg/kg. Similarly, we tested a range of doses of the 5-HT2C agonist Ro 60-0175 (0.1 – 1 mg/kg) and the 5-HT2C antagonist SB 242084 (0.03 – 0.56 mg/kg) to determine the extent to which these drugs reinstated cocaine-seeking behavior. Cocaine and SB 242084 were administered i.v. immediately before the session, followed by a saline flush to clear the catheter of residual drug solution. Ro 60-0175 was administered i.m. 30 min before the start of the session. Different doses of a particular drug were tested on different days, and each test session was separated by two or more extinction sessions. The order of testing was varied across monkeys.

Drug interaction experiments were conducted to determine the extent to Ro 60-0175 and SB 242084 attenuated or augmented the priming effects of cocaine. Initially, a range of doses of Ro 60-0175 (0.1 – 1 mg/kg) or vehicle were administered as pretreatments 30 min before a maximally effective priming dose of cocaine (1 mg/kg). Based on results of this experiment, vehicle and Ro 60-0175 (1 mg/kg) then were administered as pretreatments before a full range of cocaine priming doses (vehicle, 0.1 – 1 mg/kg). Because Ro 60-0175 has been shown to block reinstatement induced by cocaine contextual cues (e.g., Fletcher et al. 2008), an additional study directly compared the extent to which Ro 60-0175 attenuated cocaine priming-induced reinstatement in the presence and absence of response-contingent presentations of the cocaine-paired stimulus. In this study, Ro 60-0175 (1 mg/kg) was administered as a pretreatment before i.v. priming injections of cocaine (1 mg/kg) during test sessions in which the cocaine-paired stimulus was either presented contingent on responding or was omitted entirely. Finally, SB 242084 (0.1 mg/kg) was administered as a pretreatment immediately before administration of one of a range of priming doses of cocaine. This intermediate dose of SB 242084 was chosen for pretreatment to ensure against untoward effects, which have been reported at higher doses in squirrel monkeys (e.g., emesis, excessive scratching; Manvich et al. 2012b).

To determine the extent to which SB 242084 might reverse the functional antagonism of cocaine by Ro 60-0175, more extensive antagonism studies were conducted with combinations of cocaine, SB 242084, and Ro 60-0175. A comparison study also was conducted with combinations of cocaine, SB 242084, and the 5-HT transport inhibitor fluoxetine. This additional study was undertaken based on previous findings that fluoxetine, like Ro 60-0175, can significantly attenuate the effects of cocaine priming (Rüedi-Bettschen et al. 2010). SB 242084 (0.03 – 0.56 mg/kg) was administered after pretreatment with either a maximally effective dose of Ro 60-0175 (1 mg/kg) or fluoxetine (5.6 mg/kg; Rüedi-Bettschen et al. 2010) followed by a maximally effective priming dose of cocaine (1 mg/kg).

Finally, because tolerance has been shown to develop rapidly with some 5-HT drugs including 5-HT2C receptor agonists (e.g., Fone et al. 1998), we administered Ro 60-0175 or vehicle (i.m., 30 min pre-session) daily for 21 days during which time only extinction sessions were run as described above. Ro 60-0175 (or vehicle) administration commenced on day 1 of extinction. Following this period of repeated administration, we re-determined the effects of pretreatment with Ro 60-0175 on cocaine priming-induced reinstatement under identical conditions as described above (i.e., Ro 60-0175 was administered 30 min prior a maximally effective priming dose of cocaine). To avoid potential “ceiling” or “floor” effects on response rate, we chose to evaluate the effects of 0.56 mg/kg Ro 60-0175, an intermediate dose that attenuated but did not completely eliminate drug-seeking induced by cocaine priming.

Behavioral observations

Quantitative observational techniques (cf. Platt et al., 2000) were used to evaluate the behavioral effects of Ro 60-0175 in a subgroup of monkeys (N=4) that also had been subjects in the reinstatement studies. A range of doses of Ro 60-0175 (0.1 – 1 mg/kg) or vehicle was administered to the monkeys and their behavior was assessed in the home cage, during 5-min observation periods at 30 and 120 min post injection. These observation intervals were selected to capture the start and end of a typical reinstatement session. Doses of Ro 60-0175 and vehicle were studied in random order among the monkeys. Behavior was scored by a trained observer who was not informed about the drug under study. The behavioral scoring system included 11 categories (see Table 1) that were scored by recording the presence or absence of each behavior in 15-s intervals during each 5-min observation period. Modified frequency scores were calculated from these data as the number of 15-s intervals in which a particular behavior was observed.

TABLE 1.

Behavioral categories.

| Vocalization – any utterance including chirps, twitters, peeps, screeches, etc. |

| Static Posture – any static, atypical or awkward posture |

| Procumbent Posture – loose-limbed, sprawled posture; unable to maintain an upright position; lying on the floor of the chamber |

| Locomotion – any two or more directed steps in the horizontal and/or vertical plane |

| Object Exploration – any tactile or oral manipulation of features of the observational arena |

| Foraging – sweeping and/or picking through wood chip substrate |

| Self-grooming – picking, scraping, spreading or licking of fur |

| Scratching – movement of digits through fur in a rhythmic, repeated motion |

| Visual scanning – directed eye and/or head movements, usually from a sitting position |

| Rest posture – species-typical position: eyes closed, head tucked to chest, tail wrapped around upper body |

| Other – any notable behavior not defined above (e.g., yawn, sneeze) |

Analysis of drug effects

For reinstatement studies, the rate of responding in individual monkeys was computed for each session by dividing the total number of responses by the total elapsed time (excluding responses and time during TO periods). For each experimental condition, the mean response rate ± S.E.M. was calculated for the corresponding group of monkeys. All monkeys (N=10) were tested with a full range of priming doses of cocaine. Thereafter, subgroups of monkeys (N=4 – 8) participated in the various experiments involving Ro 60-0175, SB 242084, and fluoxetine alone and/or combined with cocaine priming.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SigmaStat 3.0. Data were analyzed by one-way or two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni t-tests to assess differences between control conditions and test drugs. The control conditions were either vehicle priming tests for experiments in which the drugs were tested alone, or cocaine priming with vehicle pretreatment for experiments in which cocaine was combined with other drugs.

In the observation study, individual scores for each behavior were averaged over the two 5 min observation periods, as no significant differences in scores were detected between the two time points. Scores were then averaged across subjects to provide group means and analyzed by separate one-way repeated measures ANOVAs, followed by Bonferroni t-tests. The α-level for all statistical tests was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Drugs

(−)-Cocaine hydrochloride was dissolved in 0.9% saline solution. Ro 60-0175 fumarate and fluoxetine hydrochloride were dissolved in sterile water. SB 242084 dihydrochloride was dissolved in sterile water containing 20% propylene glycol (v:v). Compounds were purchased from Tocris Cookson (Ellisville, MO) or Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Intramuscular injection volumes were 0.1 ml/kg of body weight.

Results

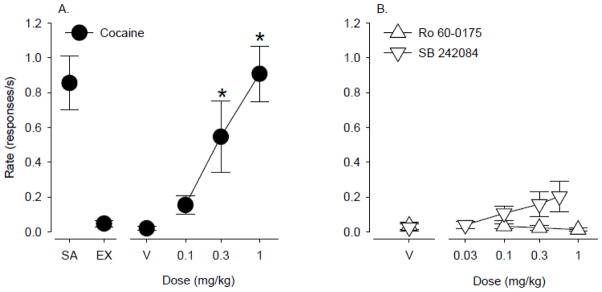

Cocaine self-administration and priming-induced reinstatement of drug seeking

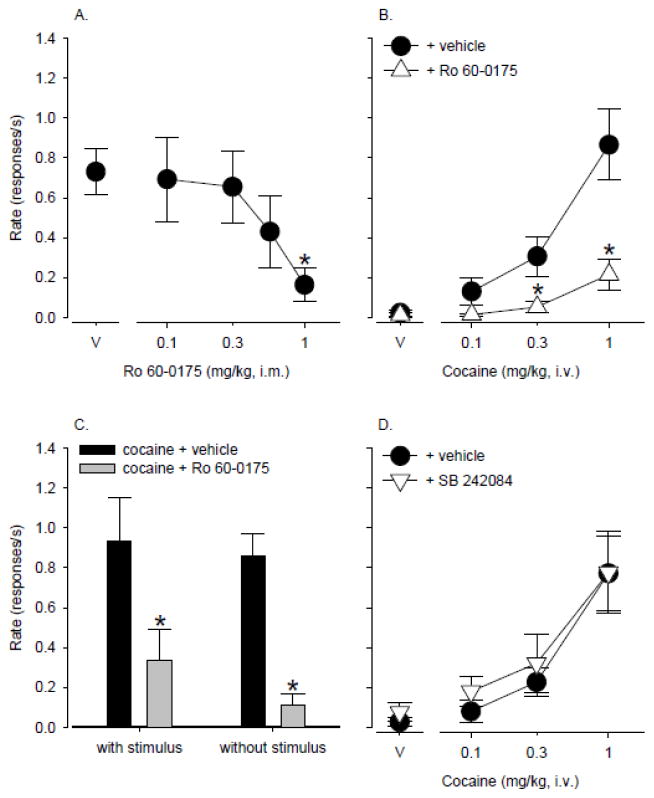

Self-administered cocaine maintained consistently high rates of responding in individual monkeys under the second-order schedule of i.v. drug injection, ranging from 0.5 – 1.8 responses/s in individual monkeys (group mean: 0.86 ± 0.15 responses/s, N=10). During extinction sessions (range: 2 – 5 days depending on the monkey), in which saline was substituted for cocaine and the cocaine-paired stimulus was omitted, responding declined and stabilized at low rates, ranging from 0 – 0.15 responses/s depending on the individual monkey (group mean: 0.05 ± 0.02 responses/s). Priming injections of cocaine (0.1 – 1 mg/kg) administered before test sessions in which the cocaine-paired stimulus was restored but only saline was available for self-administration produced reliable, dose-dependent reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior (Fig. 1A; F 3,27 = 15.8, p < 0.001). Average response rates engendered by priming with 0.3 and 1 mg/kg cocaine were significantly higher than rates obtained with vehicle (p<0.05, Bonferroni t-tests) and approached response rates that were maintained by active cocaine self-administration. Priming injections of vehicle did not induce responding significantly above the level observed during extinction (point above V). When the 5-HT agonist Ro 60-0175 or antagonist SB 242084 were administered as priming injections, neither drug increased response rates significantly above the level obtained with vehicle priming (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

A) Dose-dependent reinstatement of extinguished drug seeking induced by cocaine priming combined with restoration of the cocaine-paired stimulus (N=10). B) Neither the 5-HT2C agonist Ro 60-0175 nor the 5-HT2C antagonist SB 242084 reinstated cocaine seeking above vehicle levels (N=6 – 8). Data are means ± S.E.M. Point above SA shows response rate during active cocaine self-administration. Point above EX shows response rate during extinction sessions. Points above V show response rates following vehicle prime. *, p<0.05 compared with V.

Effects of 5-HT2C ligands on cocaine priming-induced reinstatement

Pretreatment with a range of doses of Ro 60-0175 before a maximally effective cocaine prime (1 mg/kg) resulted in dose-dependent and significant attenuation of cocaine reinstatement (Fig. 2A; F4, 20 = 8.0, p< 0.001). A dose of 1 mg/kg Ro 60-0175 significantly reduced the priming effects of cocaine (p<0.05, Bonferroni t-tests) by more than 75% compared with vehicle pretreatment. In a follow-up experiment, when Ro 60-0175 (1 mg/kg) was administered before a range of cocaine priming doses, the cocaine dose-response function was significantly affected (Fig. 2B; main effect of Ro 60-0175: F1, 5 = 13.5, p< 0.05), shifting downward and to the right. Compared to vehicle pretreatment, reinstatement induced by 0.3 and 1 mg/kg cocaine was significantly reduced by Ro 60-0175 (cocaine x Ro 60-0175 interaction: F3, 15 = 15.7, p < 0.001; p<0.05, Bonferroni t-tests). Furthermore, the extent to which Ro 60-0175 attenuated cocaine priming did not differ regardless of whether the response-contingent, cocaine-paired cues were present or absent (Fig. 2C; main effect of Ro 60-0175: F1, 3 =28.2, p < 0.05; no significant Ro 60-0175 x stimulus interaction). In contrast to effects observed with Ro 60-0175, SB 242084 did not significantly alter the priming effects of cocaine (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

A) Attenuation of cocaine priming-induced reinstatement by Ro 60-0175 (N=5). B) Ro 60-0175 shifts the cocaine priming dose-response function downward (N=6). C) Ro 60-0175 attenuated cocaine priming regardless of whether response-contingent presentations of the cocaine-paired stimulus occurred or not (N=4). D) SB 242084 did not alter the cocaine priming dose-response function (N=5). Data are means ± S.E.M. Points above V show response rates following vehicle prime. *, p<0.05 compared with V.

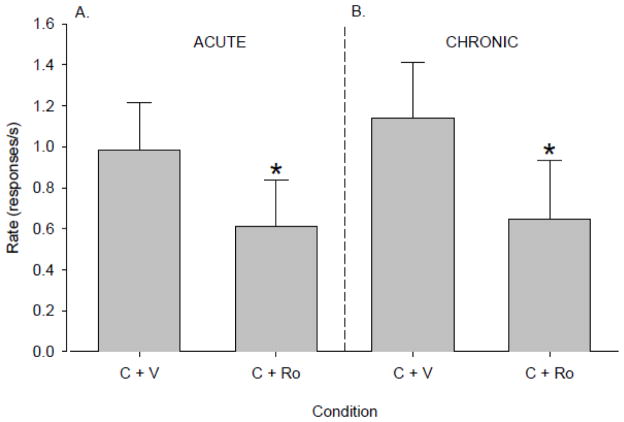

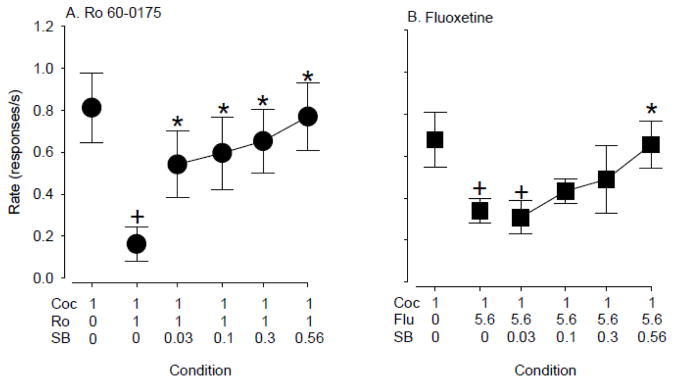

In drug interaction studies, cocaine priming-induced reinstatement of drug seeking was attenuated significantly by both Ro 60-0175 (F5, 23 =9.4, p < 0.001) and fluoxetine (F5, 15 =5.3, p < 0.01); although Ro 60-0175 was more effective, suppressing cocaine priming maximally by 80% compared to 50% for fluoxetine (Fig. 3). Both Ro 60-0175- and fluoxetine-induced attenuation of cocaine priming could be reversed by administration of SB 242084 (Ro 60-0175: F5, 23 =9.4, p < 0.001; Fluoxetine: F5, 15 =5.3, p < 0.01). In the case of attenuation of cocaine priming by Ro 60-0175, even the lowest dose of SB 242084 (0.03 mg/kg) returned responding toward baseline levels (e.g., levels observed with cocaine priming alone; p<0.05, Bonferroni t-tests). In the case of attenuation of cocaine priming by fluoxetine, only the highest dose of SB 242084 (0.56 mg/kg) restored responding to levels observed with cocaine priming alone (p<0.05, Bonferroni t-tests).

Figure 3.

SB 242084 reversed the attenuation of cocaine priming induced by A) Ro 60-0175 (N=6), and by B) fluoxetine (N=4). Data are means ± S.E.M. +, p<0.05 compared with cocaine priming alone; *, p<0.05 compared with cocaine + Ro 60-0175 or fluoxetine.

To assess the degree to which chronic administration might alter the effects of Ro 60-0175, we evaluated attenuation of cocaine priming by Ro 60-0175 both before and after 21 days of daily treatment with Ro 60-0175. A single pretreatment with 0.56 mg/kg Ro 60-0175 before priming with 1 mg/kg cocaine produced a marked attenuation of cocaine-induced reinstatement compared to vehicle pretreatment (t3 = 5.6, p < 0.02; paired t-test, Fig. 4A, compare “C + Ro” to “C + V”). Under these acute conditions, Ro 60-0175 reduced cocaine priming-induced reinstatement by 38%. When the effectiveness of Ro 60-0175 to attenuate cocaine priming-induced reinstatement was reevaluated after 21 days of chronic administration, Ro 60-0175 again significantly reduced cocaine-induced reinstatement relative to repeated vehicle pretreatment (t3 = 10.4, p < 0.002, Fig. 4B, compare “C + Ro” to “C + V”). Furthermore, after chronic administration, the extent to which Ro 60-0175 attenuated cocaine priming-induced reinstatement (approximately 43%) was essentially unchanged from acute conditions. Thus, chronic administration neither augmented nor diminished the effectiveness of Ro 60-0175 in blunting cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking.

Figure 4.

Ro 60-0175 was equally effective at attenuating the priming effects of cocaine whether administered under A) acute (N=4) or B) chronic conditions (N=4). Data are means ± S.E.M. * p<0.05 compared with “C + V”.

Observable effects of Ro 60-0175

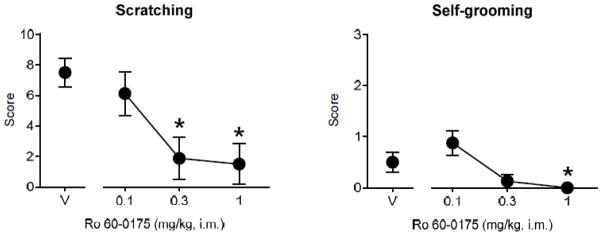

Ro 60-0175 (0.1 – 1 mg/kg) had no significant effect on the majority of behaviors examined including locomotion, object exploration, foraging, visual scanning, and vocalization. Ro 60-0175 also did not alter significantly resting, static or procumbent postures. Ro 60-0175 did, however, produce a significant reduction in the self-directed behaviors scratching (F3, 9 =5.5, p < 0.05; Figure 5, left) and self-grooming (F3, 9 =6.4, p < 0.05; Figure 5, right). Post-hoc analyses revealed that scratching was significantly reduced by 0.3 and 1 mg/kg Ro 60-0175 compared to vehicle (p<0.05, Bonferroni t-tests), and that self-grooming was significantly reduced by 1 mg/kg Ro 60-0175 compared to vehicle (p<0.05, Bonferroni t-tests).

Figure 5.

Ro 60-0175 reduced the self-directed behaviors of scratching (left) and self-grooming (right) (N=4). Data are means ± S.E.M. * p<0.05 compared with “V”.

Discussion

Previous work has demonstrated that increasing 5-HT levels in the synapse via administration of 5-HT transport inhibitors results in attenuation of the behavioral and neurochemical effects of cocaine in laboratory animals. Less is known, however, regarding the 5-HT receptor mechanisms underlying this modulation. In the present study, both the 5-HT2C receptor agonist Ro 60-0175 and the 5-HT transport inhibitor fluoxetine attenuated the priming effects of cocaine. The cocaine-attenuating effects of both drugs were reversed by the 5-HT2C antagonist SB 242084 indicating that the reduction in cocaine seeking by fluoxetine and Ro 60-0175 was due, at least in part, to specific 5-HT2C receptor-mediated agonism. Interestingly, a higher dose of SB 242084 was needed to fully reverse fluoxetine’s effects compared to the effects of Ro 60-0175. The lower potency of SB 242084 to reverse the effects of fluoxetine may reflect the fact that fluoxetine’s effects are mediated via multiple 5-HT receptor subtypes. For example, we and others have shown roles for both 5-HT1A (Rüedi-Bettschen et al. 2010) and 5-HT2A (Sawyer et al. 2012) receptors in fluoxetine’s ability to attenuate the reinstatement of drug seeking induced by cocaine priming.

Our finding that pretreatment with Ro 60-0175 attenuated the priming effects of cocaine and shifted the cocaine dose-response function downward is in accord with other recent studies showing a similar reduction in cocaine priming-induced reinstatement by Ro 60-0175 and by other 5-HT2C agonists (Bubar and Cunningham 2008, for review; Manvich et al. 2012a). Of potential note, however, is our finding that the dose of Ro 60-0175 (1 mg/kg) necessary to attenuate the priming effects of cocaine also has been reported to have rate-decreasing effects on operant responding maintained under a stimulus termination procedure in squirrel monkeys (Manvich et al. 2012a). This latter finding raises the possibility that the attenuation of reinstated drug seeking we observed might have been the result of a generalized suppression of operant behavior or induction of motor deficits instead of a specific effect on cocaine’s relapse-inducing effects. We find this explanation to be unlikely on the basis of results from our observation studies with Ro 60-0175. Across a 10-fold dose range (0.1 – 1 mg/kg), as well as a 120 min time period (chosen to encompass the reinstatement session time), Ro 60-0175 did not alter “gross” motor behavior (e.g., locomotion) or more “fine” motor behaviors (e.g., object exploration, foraging). Moreover, we did not see any increases in resting or procumbent postures that might be indicative of sedative-like effects. The lack of motoric side effects across this dose range is consistent with an earlier report in squirrel monkeys that noted the emergence of sedative-like effects at 10- to 30-fold higher doses (Martin et al. 1998).

Previous studies in rodents have shown that Ro 60-0175 can attenuate reinstatement of drug seeking induced by discrete (Burbassi and Cervo 2008) or contextual (Fletcher et al. 2008) stimuli associated with previous drug self-administration. These and other findings suggest that 5-HT2C receptors may play a key role in drug seeking induced by conditioned environmental stimuli (Burmeister et al. 2004; Burbassi and Cervo 2008). We have previously reported that in monkeys with extensive experience in the self-administration/reinstatement procedure the capacity of cocaine-paired stimuli to reinstate drug seeking tends to wane after initial testing (Spealman et al. 2004). However, these stimuli appear to continue to enhance the priming effects of cocaine, even after repeated testing (Spealman et al. 1999). Therefore, to maximize the likelihood of detecting a drug’s ability to reinstate drug seeking, we routinely restore the cocaine-paired stimulus when conducting drug priming-induced reinstatement tests. In the present study, though, this approach raises the possibility that the attenuation of cocaine priming-induced reinstatement by Ro 60-0175 was due to Ro 60-0175 blunting the priming effects of the cocaine-paired stimuli rather than the priming effects of cocaine itself. However, in a direct evaluation of this possibility, we found that Ro 60-0175 was equally effective in blocking reinstated drug seeking induced by cocaine priming alone or priming combined with presentations of a cocaine-paired stimulus. These findings suggest that, in nonhuman primates, 5-HT2C receptors play as important role in both drug- and cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking.

In contrast to Ro 60-0175, pretreatment with SB 242084 (0.1 mg/kg) before cocaine priming did not alter the shape or position of the cocaine dose-response function. This finding appears to be at odds with a recent study by Manvich et al. (2012b), which reported that SB 242084 itself has cocaine-like properties (e.g., modest stimulant and reinforcing effects when substituted for cocaine) and, when administered as a pretreatment, can enhance the priming effects of cocaine in squirrel monkeys (Manvich et al. 2012b). Effects such as these have been attributed to the antagonist’s ability to stimulate the mesolimbic system by increasing the firing rate of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area and elevating extracellular dopamine levels at terminal regions in the nucleus accumbens (Di Matteo et al. 1999; Fletcher et al. 2002). However, the dose of SB 242084 used here as a pretreatment and by Manvich et al. (2012b) has been found to induce relatively small increases in basal dopamine levels and to produce only modest enhancement of cocaine-induced increases in dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens of squirrel monkeys (Manvich et al. 2012b). A possible explanation for the discrepant finding between the two studies is simply that 0.1 mg/kg SB 242084 is a threshold dose and that if higher doses had been tested in combination with cocaine, enhancement would have been observed. Alternatively, procedural differences (e.g., route of SB 242084 administration, pretreatment interval) could have contributed to the discrepancy. Finally, differences in histories between the two monkey groups also may have altered sensitivity to the SB 242084-induced increase in dopamine levels.

Although fluoxetine reduced the priming effects of cocaine about 50%, Ro 60-0175 was more effective, attenuating the effects of cocaine by up to 80%. Additionally, in reinstatement test sessions in which the cocaine-paired stimulus was restored but only saline was available for self-administration, priming injections of Ro 60-0175 did not increase responding above vehicle-control levels. These and other findings indicating that 5-HT2C receptor agonists can attenuate the abuse-related effects of cocaine without precipitating relapse on their own raise the possibility that this class of drugs may represent a novel treatment approach for cocaine abuse. One potential concern with this strategic approach, though, is the observation that tolerance can develop to some of the behavioral effects of 5-HT2C agonists after as few as 14 days of chronic administration (e.g., 5-HT2C agonist-induced hypolocomotion; Fone et al. 1998). However, we administered Ro 60-0175 for 21 consecutive days and observed no change in its capacity to reduce the priming effects of cocaine. Likewise, Fletcher and colleagues (2008) noted that the ability of Ro 60-0175 to reduce cocaine self-administration in rats persisted across an 8 day dosing regimen. Together, these findings suggest that tolerance may not be an issue for the cocaine-attenuating properties of 5-HT2C agonists.

Finally, any prospective pharmacotherapy should be free from side effects that would hinder patient compliance. As noted earlier, our observation studies did not reveal any indication of sedative-like or motor-impairing effects with acute Ro 60-0175 treatment. We did, however, observe a reduction in self-directed scratching and grooming with intermediate-to-high doses of Ro 60-0175 (i.e., 0.3 and 1 mg/kg). Increases in self-directed behaviors have been associated with anxiety and stress in nonhuman primates and have been shown to be amenable to reduction with typical anxiolytics such as alprazolam (e.g., Schino et al. 1996; Castles et al. 1999; Troisi 2002; Birkett et al. 2005). Thus, the reduction in scratching and grooming by Ro 60-0175 may be indicative of an anxiolytic-like effect. Although speculative, this interpretation would be consistent with findings in rodents that Ro 60-0175 blocks reinstatement of drug seeking induced by the pharmacological stressor yohimbine (Fletcher et al. 2008), produces an anxiolytic-like effect in the elevated plus maze model of anxiety (Nic Dhonnchadha et al. 2003), and prevents stress-induced enhancement of brain 5-HT turnover and dopamine release (Pozzi et al. 2002; Mongeau et al. 2010). From a human treatment perspective, cocaine abstinence is frequently associated with increases in anxiety, and relapse to cocaine use is often triggered by stress. Thus, medications with anxiolytic-like properties may increase the likelihood of maintaining abstinence and preventing relapse to drug self-administration.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by DA11054, RR00168 and OD11103.

We thank K. Bano, L. Teixeira and R. Smith for technical assistance.

References

- Baker DA, Tran-Nguyen TL, Fuchs RA, Neisewander JL. Influence of individual differences and chronic fluoxetine treatment on cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:18–26. doi: 10.1007/s002130000676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbon A, Orlandi C, La Via L, Caracciolo L, Tardito D, Musazzi L, Mallei A, Gennarelli M, Racagni G, Popoli M, Barlati S. Antidepressant treatments change 5-HT2C receptor mRNA expression in rat prefrontal/frontal cortex and hippocampus. Neuropsychobiology. 2011;63:160–168. doi: 10.1159/000321593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batki SL, Washburn AM, Delucchi K, Jones RT. A controlled trial of fluoxetine in crack cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;41:137–142. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett MA, Platt DM, Tiefenbacher S, Rowlett JK. A “pharmacological stressor” model of anxiolysis in monkeys: Alprazolam attenuation of the behavioral and physiological effects of yohimbine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:S235. [Google Scholar]

- Brink CB, Viljoen SL, de Kock SE, Stein DJ, Harvey BH. Effects of myo-inositol versus fluoxetine and imipramine pretreatments on serotonin 5HT2A and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in human neuroblastoma cells. Metab Brain Dis. 2004;19:51–70. doi: 10.1023/b:mebr.0000027417.74156.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubar MJ, Cunningham KA. Distribution of serotonin 5-HT2C receptors in the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience. 2007;146:286–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubar MJ, Cunningham KA. Prospects for serotonin 5-HTR pharmacotherapy in psychostimulant abuse. Prog Brain Res. 2008;172:319–346. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00916-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbassi S, Cervo L. Stimulation of serotonin2C receptors influences cocaine-seeking behavior in response to drug-associated stimuli in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;196:15–27. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0916-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister JJ, Lungren EM, Neisewander JL. Effects of fluoxetine and d-fenfluramine on cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:146–154. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister JJ, Lungren EM, Kirschner KF, Neisewander JL. Differential roles of 5-HT receptor subtypes in cue and cocaine reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:660–668. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castles DL, Whiten A, Aureli F. Social anxiety, relationships and self-directed behaviour among wild female olive baboons. Anim Behav. 1999;58:1207–1215. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craige CP, Unterwald EM. Serotonin(2C) receptor regulation of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference and locomotor sensitization. Behav Brain Res. 2013;238:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czoty PW, Ginsburg BC, Howell LL. Serotonergic attenuation of the reinforcing and neurochemical effects of cocaine in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:831–837. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.3.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz SL, Doly S, Narboux-Neme N, Fernandez S, Mazot P, Banas SM, Boutourlinsky K, Moutkine I, Belmer A, Roumier A, Maroteaux L. 5-HT2B receptors are required for serotonin-selective antidepressant actions. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:154–163. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Matteo V, Di Giovanni G, Di Mascio M, Esposito E. SB 242084, a selective serotonin2C receptor antagonist, increases dopaminergic transmission in the mesolimbic system. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1195–1205. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip M, Bubar MJ, Cunningham KA. Contribution of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) 5-HT2 receptor subtypes to the hyperlocomotor effects of cocaine: Acute and chronic pharmacological analyses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:1246–1254. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Grottick AJ, Higgins GA. Differential effects of the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist M100,907 and the 5-HT2C receptor antagonist SB242,084 on cocaine-induced locomotor activity, cocaine self-administration and cocaine-induced reinstatement of responding. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:576–586. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Chintoh AF, Sinyard J, Higgins GA. Injection of the 5-HT2C receptor agonist Ro60-0175 into the ventral tegmental area reduces cocaine-induced locomotor activity and cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:308–318. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Rizos Z, Sinyard J, Tampakeras M, Higgins GA. The 5-HT2C receptor agonist Ro60-0175 reduces cocaine self-administration and reinstatement induced by the stressor yohimbine, and contextual cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1402–1412. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fone KC, Austin RH, Topham IA, Kennett GA, Puhani T. Effect of chronic m-CPP on locomotion, hypophagia, plasma corticosterone and 5-HT2C receptor levels in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:1707–1715. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel PS, Cunningham KA. m-Chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP) modulates the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine through actions at the 5-HT2C receptor. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:157–162. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grottic AJ, Fletcher PJ, Higgins GA. Studies to investigate the role of 5-HT2C receptors on cocaine- and food-maintained behaviors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:1183–1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Byrd LD. Serotonergic modulation of the behavioral effects of cocaine in the squirrel monkey. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1551–1559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khroyan TV, Barrett-Larimore RL, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD. Dopamine D1- and D2-like receptor mechanisms in relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior: Effects of selective antagonists and agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:680–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Sullivan NR, McAllister CE, Van de Kar LD, Muma NA. Estradiol accelerates the effects of fluoxetine on serotonin 1A receptor signaling. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.11.005. pii: S0306-4530(12)00361-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Gimenez JF, Mengod G, Palacios JM, Vilaro MT. Regional distribution and cellular localization of 5-HT2C receptor mRNA in monkey brain: Comparison with [3H]mesulergine binding sites and choline acetyltransferase mRNA. Synapse. 2001;42:12–26. doi: 10.1002/syn.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manvich DF, Kimmel HL, Howell LL. Effects of serotonin 2C receptor agonists on the behavioral and neurochemical effects of cocaine in monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012a;341:424–434. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.186981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manvich DF, Kimmel HL, Cooper DA, Howell LL. The serotonin 2C receptor antagonist SB 242084 exhibits abuse-related effects typical of stimulants in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012b;342:761–769. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.195156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JR, Bös M, Jenck F, Moreau J-L, Mutel V, Sleight AJ, Wichmann J, Andrews JS, Berendsen HHG, Broekkamp CLE, Ruigt GSF, Köhler C, van Delft AML. 5-HT2C receptor agonists: Pharmacological characteristics and therapeutic potential. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:913–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongeau R, Martin CBP, Chevarin C, Maldonado R, Hamon M, Robledo P, Lanfumey L. 5-HT2C receptor activation prevents stress-induced enhancement of brain 5-HT turnover and extracellular levels in the mouse brain: Modulation by chronic paroxetine treatment. J Neurochem. 2010;115:438–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navailles S, Moison D, Cunningham KA, Spampinato U. Differential regulation of the mesoaccumbens dopamine circuit by serotonin 2C receptors in the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens: An in vivo microdialysis study with cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:237–246. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander JL, Acosta JI. Stimulation of 5-HT2C receptors attenuates cue and cocaine-primed reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:791–800. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282f1c94b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nic Dhonnchadha BA, Bourin M, Hascoet M. Anxiolytic-like effects of 5-HT2 ligands on three mouse models of anxiety. Behav Brain Res. 2003;140:203–214. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00311-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pani PP, Trogu E, Vecchi S, Amato L. Antidepressants for cocaine dependence and problematic cocaine use. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD002950. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002950.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD. Dissociation of cocaine-antagonist properties and motoric effects of the D1 receptor partial agonists SKF 83959 and SKF 77434. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:1017–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt DM, Carey GJ, Spealman RD. Models of neurological disease (substance abuse): Self-administration in monkeys. In: Enna S, Williams M, editors. Current Protocols in Pharmacology. Wiley; New York: 2012. pp. 10.5.1–10.5.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi L, Acconcia S, Ceglia I, Invernizzi RW, Samanin R. Stimulation of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT2C) receptors in the ventrotegmental area inhibits stress-induced but not basal dopamine release in the rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurochem. 2002;82:93–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüedi-Bettschen D, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD, Platt DM. Attenuation of cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking in squirrel monkeys: Kappa opioid and serotonergic mechanisms. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210:169–177. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer EK, Mun J, Nye JA, Kimmel HL, Voll RJ, Stehouwer JS, Rice KC, Goodman MM, Howell LL. Neurobiological changes mediating the effects of chronic fluoxetine on cocaine use. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1816–1824. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schino G, Perretta G, Taglioni AM, Monaco V, Troisi A. Primate displacement activities as an ethopharmacological model of anxiety. Anxiety. 1996;2:186–191. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-7154(1996)2:4<186::AID-ANXI5>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spealman RD. Modification of behavioral effects of cocaine by selective serotonin and dopamine uptake inhibitors in squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 1993;112:93–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02247368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spealman RD, Barrett-Larimore RL, Rowlett JK, Platt DM, Khroyan TV. Pharmacological and environmental determinants of relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:327–336. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spealman RD, Lee B, Tiefenbacher S, Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Khroyan TV. Triggers of relapse: Nonhuman primate models of reinstated drug seeking. In: Bevins R, Bardo MT, editors. Motivational factors in the etiology of drug abuse. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, NE: 2004. pp. 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi A. Displacement activities as a behavioral measure of stress in nonhuman primates and human subjects. Stress. 2002;5:47–54. doi: 10.1080/102538902900012378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Preston KL, Sullivan JT, Fromme R, Bigelow GE. Fluoxetine alters the effects of intravenous cocaine in humans. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994;14:396–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]