Abstract

Background

It is estimated that approximately 10% of pancreatic cancers have a familial component. Many inheritable genetic syndromes are associated with increased risk of pancreatic cancer, such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and familial atypical multiple mole melanoma, but these conditions account for only a minority of familial pancreatic cancers. Previous studies have identified an increased prevalence of non-invasive precursor lesions, including pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia, in the pancreata of patients with a strong family history of pancreatic cancer. A detailed investigation of the histopathology of invasive familial pancreatic cancer could provide insights into the mechanisms responsible for familial pancreatic cancer, as well as aid early detection and treatment strategies.

Methods

We have conducted a blinded review of the pathology of 519 familial and 651 sporadic pancreatic cancers within the National Familial Pancreas Tumor Registry. Patients with familial pancreatic cancer were defined as individuals from families in which at least a pair of first-degree relatives have been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

Results

Overall, there were no statistically significant differences in histologic subtypes between familial and sporadic pancreatic cancers (p > 0.05). In addition, among surgical resection specimens within the study cohort, no statistically significant differences in mean tumor size, location, perineural invasion, angiolymphatic invasion, lymph node metastasis and pathologic stage were identified (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

Similar to sporadic pancreatic cancer, familial pancreatic cancer is morphologically and prognostically a heterogeneous disease.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, familial, hereditary, pathology, morphology, histology

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the 4th leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States and has the highest mortality rate of all major epithelial malignancies with a 5-year survival rate of only 5%.1, 2 The exact causes of pancreatic cancer remain unclear, but a number of factors, such as advanced age, tobacco smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus and long-standing chronic pancreatitis are associated with increased risk of pancreatic cancer.3-5 Additionally, nearly 10% of patients with pancreatic cancer report a family history of the disease and individuals with a family history of pancreatic cancer have an increased risk of developing pancreatic cancer themselves.6-9 First-degree relatives of patients with pancreatic cancer have a 2-fold increased risk of developing pancreatic cancer, individuals with two affected first-degree relatives have a 6-fold increased risk, and those with three or more affected first-degree relatives have an estimated 32-fold increased risk.8, 10 Many inheritable genetic syndromes are associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer, such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS), familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (FAMMM), hereditary breast-ovarian cancer (HBOC), hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma (HNPCC) and hereditary pancreatitis.6, 11 In addition, germline mutations in ATM and PALB2 have been identified as predisposing factors to the development of pancreatic cancer.12, 13 But, these conditions account for only a minor subset of familial cases, and thus, the genetic basis for much of familial pancreatic cancer remains elusive.

Clinicopathologic studies have helped define familial cancer syndromes of other organs. For example, the HNPCC and familial adenomatous polyposis syndromes were pathologically identified as distinct before the genes for these two syndromes were known.14 In contrast, studies comparing patients with sporadic versus familial pancreatic cancer have reported no major differences in pathology, apart from some reports suggesting differences in tumor location.8, 15, 16 Of note, Shi et al identified a significantly higher prevalence of non-invasive precursor lesions in patients with familial pancreatic cancer than in patients with sporadic disease.17 Although the study cohort was relatively small, the authors also found no statistically significant differences in histologic subtypes of infiltrating carcinomas arising in familial as compared to sporadic pancreatic cancer patients. However, in the familial group there was a statistically non-significant trend toward more adenosquamous carcinomas; a rare and aggressive neoplasm with a median overall survival of 11 months after resection.18 Thus, an understanding of the pathology of familial pancreatic cancer has the potential to define histologic subtypes of the disease, to guide therapy, and to inform early detection. We, therefore, analyzed invasive carcinomas from a large cohort of patients with familial and sporadic pancreatic cancer to compare and contrast their histomorphology and other pathologic prognostic features.

Methods

Patients

Study approval was obtained by the Johns Hopkins Hospital Institutional Review Board. All biopsies and surgical resection materials were obtained through the National Familial Pancreas Tumor Registry (NFPTR) at Johns Hopkins (www.nfptr.org).19 The NFPTR is an ongoing research study that enrolls patients with a personal or family history of pancreatic cancer. Between 1994 and the end of 2011, the NFPTR enrolled 1384 patients with familial pancreatic cancer (defined as a kindred with at least two first degree relatives with confirmed exocrine pancreatic cancer)20 and 2912 kindreds with sporadic pancreatic cancer (defined as a kindred with at least one member with pancreatic cancer but without a pair of first-degree relatives affected with the disease). Of these, 1170 had histopathology available for review. Although no germline testing was performed within this study, patients with family or personal history of PJS, FAMMM, HBOC or HNPCC were specifically excluded from this study. Of the 1170 patients, 519 satisfied criteria as familial pancreatic cancer, while 651 met criteria for sporadic pancreatic cancer. Demographic data including patient age, gender, race and family history were also recorded. Without knowledge of the patient group, hematoxylin-and-eosin stained slides for each patient including immunohistochemical stains, when available, were reviewed. Histologic subtypes of pancreatic cancer were classified based on standardized nomenclature.21 Among the surgical resections, perineural and angiolymphatic invasion were scored for each specimen. However, in cases where only 1 slide was available for histologic review, the absence of each of these parameters was scored as unknown (Table 2). The presence of lymph node metastases was also scored, but if no lymph nodes were submitted for pathologic review, this parameter was scored as unknown. Gross reports were reviewed for each resection to record tumor location and size. Tumors were staged using the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging Manual.22

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic comparison of surgically resected familial and sporadic pancreatic cancers.

| Patient or tumor features | Total, n = 563 | Familal, n = 166 | Sporadic, n = 397 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range), y | 64.6 (21 - 87) | 65.0 (39 - 86) | 64.5 (21 - 87) | 0.802 |

| Mean tumor size, cm | 3.33 (0.1 - 10) | 3.24 (0.1 - 6.5) | 3.36 (0.1 - 10) | 0.120 |

| Location | ||||

| Head | 438 (78%) | 136 (82%) | 302 (76%) | 0.402 |

| Body | 67 (12%) | 13 (8%) | 54 (14%) | |

| Tail | 44 (8%) | 13 (8%) | 31 (8%) | |

| Uncinate | 7 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 5 (1%) | |

| Diffuse | 7 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 5 (1%) | |

| Perineural invasion | 521 (93%) | 157 (95%) | 364 (92%) | 0.159 |

| Angiolymphatic invasion | 301 (53%) | 83 (50%) | 218 (55%) | 0.309 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 407 (72%) | 119 (72%) | 288 (73%) | 0.837 |

| AJCC TNM staging | ||||

| Stage IA | 20 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 16 (3%) | 0.891 |

| Stage IB | 52 (9%) | 16 (10%) | 36 (9%) | |

| Stage IIA | 82 (14%) | 27 (16%) | 55 (13%) | |

| Stage IIB | ||||

| T1N1M0 | 9 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 6 (2%) | |

| T2N1M0 | 71 (13%) | 21 (13%) | 50 (13%) | |

| T3N1M0 | 313 (56%) | 92 (55%) | 221 (56%) | |

| Stage III | 9 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 7 (2%) | |

| Stage IV | 7 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (2%) |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses to assess differences between familial and sporadic pancreatic cancers were compared using Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was defined as a p value < 0.05. Data analysis was conducted using STATA, version 12 (Statacorp, College Station, TX) and SPSS Statistical software, version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

The clinical demographics and histopathology of the 519 familial and 651 sporadic pancreatic cancers are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic comparison between familial and sporadic pancreatic cancers.

| Patient or tumor features | Total, n = 1170 | Familal, n = 519 | Sporadic, n = 651 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range), y | 64.7 (21 - 105) | 65.3 (29 - 95) | 64.2 (21 - 105) | 0.802 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 587 (50%) | 243 (47%) | 344 (53%) | 0.060 |

| Female | 583 (50%) | 276 (53%) | 307 (47%) | |

| Race | n = 386 | n = 76 | n = 310 | |

| Caucasian | 360 (93%) | 71 (93%) | 289 (93%) | 0.191 |

| Black | 10 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (3%) | |

| Other | 16 (4%) | 5 (7%) | 11 (4%) | |

| Histologic subtype | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma, NOS | 1122 (96%) | 499 (96%) | 623 (96%) | 0.383 |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 14 (1%) | 6 (1%) | 8 (1%) | |

| Colloid carcinoma | 14 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 10 (2%) | |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 9 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast like giant cells |

2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Medullary carcinoma | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Large-duct type adenocarcinoma | 5 | 1 | 4 (1%) | |

| Acinar cell carcinoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mixed ductal-neuroendocrine | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Mixed ductal-acinar-neuroendocrine | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Familial pancreatic cancers

Among the familial cohort, patients at clinical presentation ranged in age from 29 to 95 years (mean, 65.3 years) and there was a slight female predominance (n = 276, 53%). Racial data were available for all (100%) patients, the vast majority of which were Caucasian (n = 490, 94%). Microscopically, the vast majority of the invasive carcinomas in the familial group were classic infiltrating ductal adenocarcinoma (499 of 519, 96%). Other types of invasive carcinoma identified in the familial group included 6 (1%) adenosquamous carcinomas, 4 (1%) colloid carcinomas, 5 (1%) undifferentiated carcinomas, one undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells, one medullary carcinoma, one large-duct type adenocarcinoma, one mixed ductal-neuroendocrine carcinoma and one mixed ductal-acinar-neuroendocrine carcinoma. When compared to the sporadic pancreatic cancer cohort, no statistically significant differences in mean patient age (p = 0.80), gender (p = 0.06), race (p = 0.63) and histologic subtype (p = 0.38) were identified by univariate analysis.

Surgically resected cases

Of the 1170 specimens with histopathology within the registry, 563 (48%) were surgical resections that corresponded to 166 familial and 397 sporadic pancreatic cancers (Table 2). The 166 surgically resected pancreatic cancers in the familial cohort ranged in size from 0.1 to 6.5 cm (mean, 3.24 cm) and were predominantly centered within the head of the pancreas (n = 136, 82%). Perineural invasion (n = 151, 91%), angiolymphatic invasion (n = 83, 50%) and lymph node metastasis (n = 119, 72%) were frequent findings. Based on the seventh edition of the AJCC pathologic prognostic staging system, the familial pancreatic cancers were classified as follows: 4 (2%) stage IA, 12 (7%) stage IB, 26 (16%) stage IIA, 116 (70%) stage IIB, 2 (1%) stage III and 1 (1%) stage IV. No significant differences between resected familial and sporadic pancreatic cancers were identified with regards to mean tumor size (p = 0.82), location (p = 0.40), perineural invasion (p = 0.10), angiolymphatic invasion (p = 0.05), lymph node metastasis (p = 0.77) and pathologic stage (p = 0.98).

Discussion

Overall, there were no statistically significant differences in histologic subtypes between familial and sporadic invasive pancreatic cancers. Furthermore, among surgical resections, no differences in mean tumor size, location, perineural invasion, angiolymphatic invasion, lymph node metastasis and pathologic stage were identified. Similar to sporadic pancreatic cancer, familial pancreatic cancer is morphologically and prognostically a heterogeneous disease.

A number of genetic syndromes have been linked to specific histologic subtypes of pancreatic cancer. For example, pancreatic cancer has been described in kindreds with HNPCC. Patients with HNPCC harbor germline mutations in one of the DNA mismatch repair genes including MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 and MSH6. Inactivation of one of these proteins results in microsatellite instability and a distinctive medullary histologic appearance.23-25 Recognition of the medullary morphology can be used to suggest the possibility of HNPCC in a patient with pancreatic cancer and initiate microsatellite instability testing.6 In addition, PJS is associated with germline mutations in the STK11/LKB1 gene and characterized by mucocutaneous melanocytic macules and hamartomatous polyps of the gastrointestinal tract. Individuals with PJS have a 132-fold increased risk of developing pancreatic cancer.26, 27 A number of studies have observed the presence of IPMN precursor lesions in patients with PJS.28 More importantly, the association between PJS and IPMNs has significant ramifications in pancreatic cancer screening as most clinically significant IPMNs are large enough that they can be detected by radiographic imaging.29, 30 In contrast, germline mutations in the CDKN2A gene, which have been linked to FAMMM, have not been reported to be associated with unique histopathologic findings. Similarly, patients with PRSS1 hereditary pancreatitis, who are predisposed to developing pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, do not demonstrate any defining morphologic features. Considering the presence of multiple gene-specific pathologic findings, the lack of detectable differences between familial and sporadic pancreatic cancers may indicate that many susceptibility genes instead of just one remain to be identified. Further, correlation with other predisposing genes (e.g. BRCA2, PALB2, ATM, etc.) rather than a heterogeneous group of familial pancreatic cancer patients may reveal distinct morphologic and prognostic features.

Despite the lack of detectable differences in the histopathology between familial and sporadic pancreatic cancers, several studies have reported a higher frequency of precursor lesions in familial pancreatic cancer patients.29-34 In fact, both PanINs and incipient IPMNs can be quite extensive with a 2.78-fold higher prevalence per square centimeter in familial compared to sporadic cases.17, 35 Furthermore, these precursor lesions in familial pancreatic cancer patients tend to be of a higher-grade.17 Thus, although the histomorphology of familial pancreatic cancer may have limited potential in identifying kindreds with this disease, the presence of numerous precursor lesions may be more informative.

In summary, we report the pathology of the largest familial pancreatic cancer cohort described to date. While certain subtypes of pancreatic cancer have historically been linked with genetic syndromes, the current study illustrates no statistically significant differences between the morphologies of familial versus sporadic pancreatic cancers. Despite the increased prevalence of precursor lesions, familial pancreatic cancer is a heterogeneous disease. However, correlation with specific, predisposing germline mutations may yield distinct and clinically significant pathologic findings.

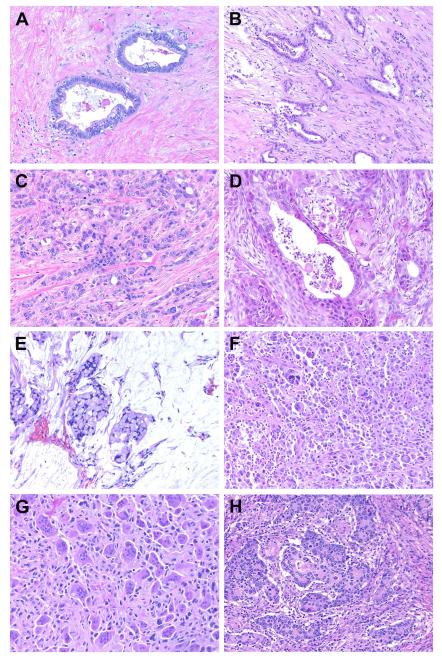

Figure 1.

Histopathology of familial pancreatic cancer. In addition to conventional ductal adenocarcinoma (A, well-differentiated; B, moderately-differentiated; and C, poorly-differentiated), multiple histologic subtypes of invasive pancreatic cancer were identified within the familial pancreatic cancer cohort. These include (D) adenosquamous carcinoma, (E) colloid carcinoma, (F) undifferentiated carcinoma (G) undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells, (H) medullary carcinoma, acinar cell carcinoma (not shown) and mixed variants (not shown).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by NIH SPORE grant CA62924, R01CA097075, The Michael Rolfe Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research, and Susan Wojcicki and Dennis Troper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Hariharan D, Saied A, Kocher HM. Analysis of mortality rates for pancreatic cancer across the world. HPB (Oxford) 2008;10(1):58–62. doi: 10.1080/13651820701883148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. 2013 http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/. 1975-2010.

- 3.Partensky C. Toward a better understanding of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: glimmers of hope? Pancreas. 2013;42(5):729–39. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318288107a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahlgren JD. Epidemiology and risk factors in pancreatic cancer. Semin Oncol. 1996;23(2):241–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mack TM, Yu MC, Hanisch R, Henderson BE. Pancreas cancer and smoking, beverage consumption, and past medical history. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;76(1):49–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi C, Hruban RH, Klein AP. Familial pancreatic cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(3):365–74. doi: 10.5858/133.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Permuth-Wey J, Egan KM. Family history is a significant risk factor for pancreatic cancer: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Cancer. 2009;8(2):109–17. doi: 10.1007/s10689-008-9214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein AP, Brune KA, Petersen GM, et al. Prospective risk of pancreatic cancer in familial pancreatic cancer kindreds. Cancer Res. 2004;64(7):2634–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tersmette AC, Petersen GM, Offerhaus GJ, et al. Increased risk of incident pancreatic cancer among first-degree relatives of patients with familial pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(3):738–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grover S, Syngal S. Hereditary pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(4):1076–80. 80, e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hruban RH, Canto MI, Goggins M, Schulick R, Klein AP. Update on familial pancreatic cancer. Adv Surg. 2010;44:293–311. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts NJ, Jiao Y, Yu J, et al. ATM mutations in patients with hereditary pancreatic cancer. Cancer discovery. 2012;2(1):41–6. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones S, Hruban RH, Kamiyama M, et al. Exomic sequencing identifies PALB2 as a pancreatic cancer susceptibility gene. Science. 2009;324(5924):217. doi: 10.1126/science.1171202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynch HT, Rozen P, Schuelke GS. Hereditary colon cancer: polyposis and nonpolyposis variants. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 1985;35(2):95–114. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.35.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen GM, de Andrade M, Goggins M, et al. Pancreatic cancer genetic epidemiology consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(4):704–10. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barton JG, Schnelldorfer T, Lohse CM, et al. Patterns of pancreatic resection differ between patients with familial and sporadic pancreatic cancer. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2011;15(5):836–42. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1417-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi C, Klein AP, Goggins M, et al. Increased Prevalence of Precursor Lesions in Familial Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(24):7737–43. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voong KR, Davison J, Pawlik TM, et al. Resected pancreatic adenosquamous carcinoma: clinicopathologic review and evaluation of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation in 38 patients. Hum Pathol. 2010;41(1):113–22. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hruban RH, Canto MI, Griffin C, et al. Treatment of familial pancreatic cancer and its precursors. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2005;8(5):365–75. doi: 10.1007/s11938-005-0039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brand RE, Lerch MM, Rubinstein WS, et al. Advances in counselling and surveillance of patients at risk for pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2007;56(10):1460–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.108456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hruban RH, Pitman MB, Klimstra DS. Tumors of the Pancreas. The American Registry of Pathology; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Carducci MA, Compton CC. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th edn Springer; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goggins M, Offerhaus GJ, Hilgers W, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinomas with DNA replication errors (RER+) are associated with wild-type K-ras and characteristic histopathology. Poor differentiation, a syncytial growth pattern, and pushing borders suggest RER+ Am J Pathol. 1998;152(6):1501–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilentz RE, Goggins M, Redston M, et al. Genetic, immunohistochemical, and clinical features of medullary carcinoma of the pancreas: A newly described and characterized entity. Am J Pathol. 2000;156(5):1641–51. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65035-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banville N, Geraghty R, Fox E, et al. Medullary carcinoma of the pancreas in a man with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer due to a mutation of the MSH2 mismatch repair gene. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(11):1498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersmette AC, et al. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(6):1447–53. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su GH, Hruban RH, Bansal RK, et al. Germline and somatic mutations of the STK11/LKB1 Peutz-Jeghers gene in pancreatic and biliary cancers. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(6):1835–40. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65440-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato N, Rosty C, Jansen M, et al. STK11/LKB1 Peutz-Jeghers Gene Inactivation in Intraductal Papillary-Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(6):2017–22. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canto MI, Goggins M, Yeo CJ, et al. Screening for pancreatic neoplasia in high-risk individuals: an EUS-based approach. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(7):606–21. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canto MI, Goggins M, Hruban RH, et al. Screening for early pancreatic neoplasia in high-risk individuals: a prospective controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(6):766–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.02.005. quiz 665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potjer TP, Schot I, Langer P, et al. Variation in precursor lesions of pancreatic cancer among high-risk groups. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(2):442–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brentnall TA, Bronner MP, Byrd DR, Haggitt RC, Kimmey MB. Early diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic dysplasia in patients with a family history of pancreatic cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(4):247–55. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-4-199908170-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Canto MI, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, et al. Frequent detection of pancreatic lesions in asymptomatic high-risk individuals. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(4):796–804. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.005. quiz e14-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langer P, Kann PH, Fendrich V, et al. Five years of prospective screening of high-risk individuals from families with familial pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2009;58(10):1410–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.171611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brune K, Abe T, Canto M, et al. Multifocal neoplastic precursor lesions associated with lobular atrophy of the pancreas in patients having a strong family history of pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(9):1067–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]