Abstract

Objective

Melanoma incidence and mortality are increasing among United States (U.S.) adults. Currently, routine skin cancer screening total body skin examinations (TBSEs) by a physician are not recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); while organizations such as the American Cancer Society recommend screening. Currently, there are limited data on the prevalence, correlates, and trends of TBSE among U.S. adults.

Methods

We analyzed data by race/ethnicity, age, and skin cancer risk level, among other characteristics from three different National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) cancer control supplements conducted every five years since 2000 in random U.S. households. High-risk status and middle-risk status were defined based on the USPSTF criteria (age, race, sunburn, and family history).

Results

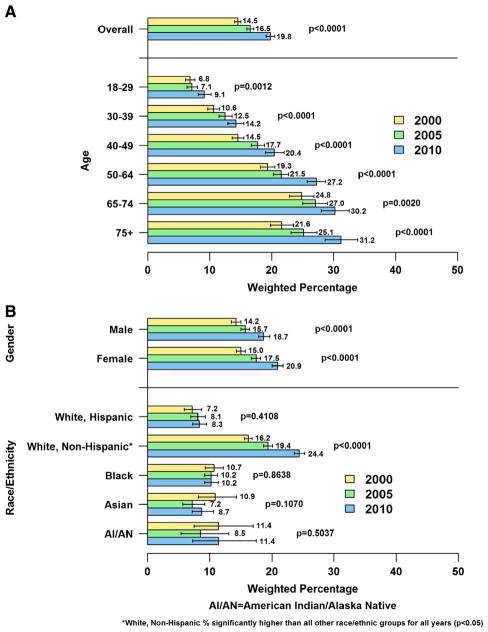

Prevalence of having at least one TBSE increased from 14.5 in 2000 to 16.5 in 2005 to 19.8 in 2010 (P = 0.0001). In 2010, screening rates were higher among the elderly, the fair-skinned, those reporting sunburn(s), and individuals with a family history of skin cancer. Approximately 104.7 million (51.1%) U.S. adults are at high-risk for developing melanoma, of which 24.0% had at least one TBSE.

Conclusions

TBSE rates have been increasing since 2000 both overall and among higher-risk groups. Data on screening trends could help tailor future prevention strategies.

Keywords: Skin cancer, Cancer screening, Early diagnosis of cancer, Melanoma

Introduction

Skin cancer is the most common cancer in the United States. In 2010, there were an estimated two million cases of non-melanoma skin cancer with less than 1000 deaths (NCI, 2013); while, in 2009, there were over 61,646 melanoma cases and 9199 deaths due to melanoma (USCS, 2013). Melanoma is one of the few cancers that has been increasing in both incidence and mortality in the U.S. (Rogers et al., 2010). During the past three decades, the melanoma rates have increased nearly three-fold, from 7.9 per 100,000 in 1975 to 23.1 per 100,000 in 2009. Mortality from melanoma has increased by 33%, from 2.1 per 100,000 in 1975 to 2.8 per 100,000 in 2009 (Howlader et al.). Annual direct costs of treatment for melanoma were estimated to be $44.9 million for Medicare recipients with previously diagnosed cancers and $932.5 million for all Americans with newly diagnosed cases (Guy et al., 2012).

Although there are limited data on the mortality benefit of population-based TBSE screening, studies have found that periodic total body skin examinations (TBSEs) conducted by physicians may increase the likelihood of detecting melanomas at relatively earlier stages, thereby potentially increasing survival time and quality of life and decreasing costs of treatment (Goldberg et al., 2007; Guy et al., 2012). The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (2009) found insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of total body skin examination by a clinician or patient skin self-examination for the early detection of skin cancer in the general U.S. adult population and even among high-risk groups (USPSTF, 2001; Wolff et al., 2009). The American Cancer Society's (ACS) evidence- and consensus-based recommendation for 2013 is that individuals aged ≥20 years should undergo routine screening for skin cancer during their periodic health visit. The American Academy of Dermatology recommends annual screening TBSEs, and also advocates skin self-examination through campaigns such as “Melanoma Monday” (AAD, 2012) (see Appendix 1 for more skin cancer screening guidelines.) The ACS and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists support skin cancer screening of high-risk individuals (ACOG, 2012; ACS, 2013) The USPSTF defines high-risk groups for melanoma as follows: fair-skinned men and women aged >65 years, as well as those who: report sunburn(s), have a family history of skin cancer, and have >50 or atypical moles.

Lack of agreement among major U.S. medical organizations regarding the use of TBSE for skin cancer screening may impact screening practices within the U.S. population (AAD, 2012; ACS, 2013; Koh et al., 1996; USPSTF, 2012; Wolff et al., 2009). One study using the 2005 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data found that skin cancer screening rates were considerably lower (17%) than the screening rates for breast (54%) and colorectal (51%) cancers, where routine screening is generally recommended (Coups et al., 2010).

At present, there are limited data on TBSE prevalence and trends over time, and characteristics of those screened compared to those not screened in the general U.S. adult population as well as high-risk adult groups. Our study utilizes nationally representative data from the NHIS to add to the research in those areas.

Methods

Our data source, the NHIS, is an annual, cross-sectional, household interview survey of the civilian, non-institutionalized U.S. adult population, which has been conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics (CDC/NCHS) since 1960. NHIS is a public-use dataset that does not include identifiable data; thus, our analysis is exempt from IRB review. Each year, members of approximately 35,000 households participate in the NHIS. In 2000, 2005, and 2010, the NHIS included a cancer control supplement, in which survey respondents were asked, “Have you ever had all of your skin from head to toe checked for cancer either by a dermatologist or some other kind of doctor?” Those who replied that they had were then asked follow-up questions regarding the timing of their most recent TBSE. The supplement was administered to one randomly selected adult per household. The survey samples, which refer to the total number of sample adults, consisted of 32,374 respondents in 2000, 31,428 in 2005, and 27,157 in 2010. Response rates were 72.1% in 2000, 69.0% in 2005, and 60.8% in 2010. We excluded respondents with a history of any type of skin cancer (2000: n = 700; 2005: n = 750; 2010: n = 753) from our main analysis because their TBSEs may have been performed to monitor the progress of a previously diagnosed cancer rather than to detect a previously undiagnosed cancer. In our analyses, we estimated the percentage of U.S. adults who had ever obtained a TBSE, both overall and by age, sex, and race/ethnicity (a proxy for level of pigmentation). Percentages were age-standardized to the 2000 U.S. standard million population (Klein and Schoenborn, 2001). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals around the percentages were calculated based on a logit transformation. Statistical testing for differences in age-standardized percentages was performed using general linear contrasts. Year was treated as a categorical variable in order to test for any differences over time rather than assuming a linear trend. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to calculate adjusted TBSE percentages as predictive margins. The predictive margin for a specific group represents the average predicted response if everyone in the sample had been in that group. An additional multivariable logistic regression model was fit to assess trends in TBSE over time. Race (Hispanic White, non-Hispanic White, non-White) by year interaction terms were included to determine if the year effect varied by race. Skin reaction to sunlight (both short- and long-term exposure) and selected family history (any skin cancer and any cancer) variables were excluded from the models to avoid collinearity with protective behaviors and family history of melanoma/ non-melanoma skin cancer, respectively. TBSE patterns over the past 10 years were also analyzed among the high-risk individuals aged >65 years, those who reported 1 or more sunburn(s), and those with a family history of skin cancer. Statistical testing for the age-adjusted and multivariable analyses was based on the Wald F test. SAS version 9.2 and SUDAAN version 10.0.1 were used to account for the complex sampling design and to allow for weighting of the estimates.

Using USPSTF guidelines, we defined the following groups as being at high-risk for skin cancer: non-Hispanic White men and women aged >65 years, respondents who reported having been sunburned, and respondents with a family history of skin cancer. High risk characteristics such as many moles (>50) or atypical moles could not be ascertained as they were not asked on the NHIS. Medium-risk individuals were defined as non-Hispanic White individuals aged ≤65 years who did not meet the high-risk criteria. Low-risk individuals were the remaining group of U.S. adults. Numbers of high-, medium-, and low-risk U.S. adults were calculated using NHIS population total estimates. The numbers of individuals screened were calculated by multiplying the NHIS screening percentage times the U.S. adult population estimate for each high-, medium-, and low-risk group (and the high-risk sub-groups). We looked to assess this risk classification by examining the distribution in those respondents that were excluded due to a history of skin cancer. For all three years combined, 76.0% of those with a skin cancer history were considered high-risk with 22.1% medium-risk and only 1.8% low-risk.

Results

Reports of ever having had a TBSE increased nationally from 14.5% [95% CI (14.0–15.0)] in 2000 to 16.5% [95% CI (14.0–15.0)] in 2005 to 19.8% [95% CI (19.1–20.5)] in 2010 (P < 0.0001). Between 2000, 2005, and 2010, there were significant increases in screening among all age groups, with the most screenings being reported among non-Hispanic Whites and individuals age 50 and above (all P < 0.05). TBSE rates increased each year among both men and women. In 2010, the percentage of adults who had ever had a TBSE was positively associated (P < 0.0001) with having more education, doing more physical activity, having had a severe skin reaction to sunlight after 1 h or longer exposure, using sun protection (e.g., wearing a long-sleeved shirt, wearing a wide-brimmed hat, or using sunscreen with an SPF rating of 15 or greater), and going to a tanning salon in the past year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Percentage of U.S. adults who ever had a total body skin examination, overall and by selected characteristics, NHIS 2010.

| Characteristic: | N | Age-Std %a (95% CI)* | Predictive marginsb % (95% CI)** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 24,421 | 19.8 (19.1–20.5) | 20.1 (19.3–20.8) |

| Age (years) | 24,421 | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 |

| 18–29 | 4947 | 9.1 (8.2–10.2) | 12.1 (10.7–13.6) |

| 30–39 | 4527 | 14.2 (12.9–15.5) | 15.3 (13.9–16.7) |

| 40–49 | 4399 | 20.4 (19.0–22.0) | 20.2 (18.8–21.8) |

| 50–64 | 5938 | 27.2 (25.7–28.7) | 24.5 (23.1–25.9) |

| 65–74 | 2467 | 30.2 (28.0–32.5) | 26.1 (23.8–28.5) |

| ≥75 | 2143 | 31.2 (28.6–33.9) | 27.9 (24.7–31.3) |

| Sex | 24,421 | P = 0.0005 | P = 0.4346 |

| Male | 10,743 | 18.7 (17.9–19.7) | 20.3 (19.3–21.4) |

| Female | 13,678 | 20.9 (20.0–21.8) | 19.8 (18.9–20.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | 24,421 | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 |

| White, Hispanic | 4348 | 8.3 (7.3–9.5) | 13.6 (11.5–16.1) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 13,803 | 24.4 (23.6–25.3) | 22.4 (21.5–23.3) |

| Black | 4263 | 10.2 (9.2–11.4) | 13.2 (11.7–14.9) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1644 | 8.7 (7.2–10.6) | 9.9 (8.1–12.0) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 241 | 11.4 (7.3–17.5) | 14.6 (9.2–22.3) |

| Other/multiracial | 122 | 6.3 (3.3–11.7) | 16.7 (9.1–28.8) |

| Region | 24,421 | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 |

| South | 8949 | 19.3 (18.3–20.5) | 20.9 (19.8–22.0) |

| Midwest | 5369 | 18.3 (16.9–19.7) | 17.5 (16.2–18.7) |

| Northeast | 3883 | 25.2 (23.5–26.9) | 24.6 (23.1–26.2) |

| West | 6220 | 18.0 (16.9–19.2) | 18.2 (17.1–19.3) |

| Education | 24,326 | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 |

| <HS | 4209 | 8.0 (7.1–9.0) | 12.7 (11.2–14.4) |

| HS grad/GED | 6423 | 14.5 (13.5–15.6) | 16.3 (15.2–17.4) |

| Some college/tech school | 7291 | 21.1 (20.0–22.2) | 20.5 (19.3–21.7) |

| College graduate | 6403 | 29.4 (28.0–30.8) | 25.1 (23.8–26.5) |

| Usual place of health care | 24,417 | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.0358 |

| No | 4550 | 10.2 (8.9–11.8) | 17.9 (16.0–19.9) |

| Yes | 19,867 | 21.4 (20.6–22.1) | 20.3 (19.5–21.1) |

| Health care coverage | 24,353 | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 |

| No | 4698 | 8.4 (6.5–10.9) | 15.9 (13.9–18.2) |

| Yes | 19,655 | 21.9 (21.1–22.7) | 20.5 (19.8–21.3) |

| Physical activityc | 23,954 | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 |

| No activity | 8597 | 12.6 (11.7–13.5) | 16.0 (15.0–17.1) |

| Some activity | 5308 | 19.4 (18.1–20.8) | 19.3 (18.0–20.7) |

| Meets/exceeds recommendations | 10,049 | 25.7 (24.7–26.8) | 22.9 (22.0–24.0) |

| Sun protectiond | 24,011 | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 |

| Do not go out in sun | 1163 | 11.9 (9.7–14.6) | 19.6 (17.0–22.4) |

| Sometimes/rarely/never | 13,092 | 15.1 (14.3–15.9) | 16.7 (15.9–17.7) |

| Always/most of the time | 9756 | 26.8 (25.7–27.9) | 23.8 (22.7–24.8) |

| Use of tanning salon in past year | 24,376 | P = 0.0025 | P = 0.0360 |

| No | 23,218 | 19.4 (18.7–20.1) | 19.9 (19.1–20.6) |

| Yes | 1158 | 26.6 (22.3–31.4) | 23.1 (20.2–26.2) |

| Sunburns in past year | 24,307 | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.2653 |

| 0 | 16,318 | 17.8 (17.0–18.6) | 20.5 (19.6–21.4) |

| 1–2 | 6262 | 23.1 (21.7–24.6) | 19.6 (18.6–20.7) |

| 3 or more | 1727 | 23.6 (20.9–26.4) | 18.8 (16.8–21.1) |

| Personal history of any cancer | 24,421 | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 |

| No | 22,988 | 18.9 (18.3–19.6) | 19.3 (18.6–20.1) |

| Yes | 1433 | 34.8 (30.2–39.7) | 29.8 (27.2–32.6) |

| Family history of skin cancer (non-melanoma) | 23,802 | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.0010 |

| No | 23,333 | 19.5 (18.8–20.1) | 19.9 (19.2–20.6) |

| Yes | 469 | 35.2 (30.1–40.8) | 25.9 (22.2–30.0) |

| Family history of melanoma | 23,802 | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 |

| No | 23,357 | 19.4 (18.8–20.1) | 19.8 (19.1–20.5) |

| Yes | 445 | 39.2 (33.4–45.2) | 30.7 (26.5–35.2) |

| Characteristics excluded from model due to issues with collinearity or singularity: | |||

| Skin reaction, 1 he | 23,724 | P < 0.0001 | |

| Do not go out in sun | 1698 | 13.9 (11.5–16.7) | |

| No sunburn, tanning, nothing | 10,623 | 14.6 (13.7–15.5) | |

| Mild sunburn, some tanning | 5291 | 23.8 (22.5–25.1) | |

| Severe sunburn | 6112 | 25.2 (24.0–26.4) | |

| Skin reaction, long exposuree | 23,349 | P < 0.0001 | |

| Do not go out in sun | 2168 | 6.0 (4.9–7.4) | |

| Very dark tan | 3213 | 8.0 (6.9–9.4) | |

| Moderate tan | 7592 | 8.9 (8.2–9.7) | |

| Mild tan | 7223 | 8.3 (7.5–9.2) | |

| Repeated sunburns/freckled | 3123 | 12.3 (11.1–13.7) | |

N = unweighted sample size; model N = 22,018 with 4099 events.

CI = confidence interval; Std = Standardized.

For age standardized %: P-value for global test of association calculated using Wald F test.

For predictive margins %: P-value based on the Wald F test statistic for the simultaneous test that all beta coefficients associated with a given variable are equal to 0.

Percentages are age-standardized to the 2000 U.S. standard population according to the following age groups: 18–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, and ≥70.

Predictive margins calculated from multivariable logistic regression model including all covariates in Table 2 except where noted. In addition, the following variables not included in the table were also adjusted for: employment status, primary language spoken, marital status, cigarette smoking, excessive alcohol use, physician seen in past year, self-reported health status, routine consumption of multivitamins, and body mass index.

The following formula was used to calculate metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes per week from the number of minutes per week of moderate and vigorous exercise: 4.5 × moderate minutes per week + 7.0 × vigorous minutes per week. Physical activity was defined as no activity (MET minutes per week = 0), some activity (MET minutes per week = 1–<675), or meets/exceeds recommendations (MET minutes per week ≥ 675) (Ainsworth BE and 2000).

Defined as wearing a long-sleeved shirt, wearing a wide-brimmed hat, or using sunscreen with an SPF rating of 15 or greater.

Characteristic excluded from model due to issues with collinearity or singularity.

There was a significant race by year interaction in the adjusted model predicting ever having a TBSE (P < 0.0001) (Table 2). A significant increase in ever having a TBSE was found among non-Hispanic Whites between 2000 and 2010 (adjusted odds ratio [OR] for 2010 vs. 2000 = 1.66 [95% CI: 1.55–1.79]). In 2010, the odds of ever having a TBSE among non-Hispanic Whites were about 2.5 times those of Hispanic Whites and non-Whites.

Table 2.

Adjusteda associations of year and race on ever having a total body skin examination among U.S. adults; NHIS 2000, 2005, and 2010.

| Raceb | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| 2000 | |

| White non-Hispanic vs. White Hispanic | 1.71 (1.37–2.15) |

| White non-Hispanic vs. non-White | 1.26 (1.10–1.44) |

| 2005 | |

| White non-Hispanic vs. White Hispanic | 1.82 (1.55–2.15) |

| White non-Hispanic vs. non-White | 1.68 (1.46–1.94) |

| 2010 | |

| White non-Hispanic vs. White Hispanic | 2.49 (2.10–2.95) |

| White non-Hispanic vs. non-White | 2.43 (2.14–2.77) |

| Year† | |

| White Hispanic | |

| 2005 vs. 2000 | 1.18 (0.91–1.53) |

| 2010 vs. 2000 | 1.15 (0.88–1.49) |

| White non-Hispanic | |

| 2005 vs. 2000 | 1.25 (1.17–1.35) |

| 2010 vs. 2000 | 1.66 (1.55–1.79) |

| Non-White | |

| 2005 vs. 2000 | 0.94 (0.77–1.14) |

| 2010 vs. 2000 | 0.86 (0.72–1.02) |

Adjusted for age, sex, marital status, education, region, BMI, smoking status, excessive alcohol use, health status, physical activity level, number of sunburns in past year, family history of melanoma, family history of non-melanoma skin cancer, personal history of cancer, usual source of care, seen physician in past year, sun protection, health care coverage, and employment status.

There was a significant race/ethnicity by year interaction (P ≤ 0.001). Odds ratios for race/ ethnicity and year are presented within levels of the other factor.

Our estimates also show that at least half of the U.S. adult population, or approximately 104.7 million adults would be considered high-risk for skin cancer based on the USPSTF criteria. Among the selected high-risk individuals, 24.0% or about 25.3 million adults had a TBSE once in their lifetime, and 11.3% or about 12.0 million adults had a TBSE in the past year. Among the medium-risk group, 24.2% or about 11.9 million adults had a TBSE once in their lifetime, and 9.5% or approximately 4.7 million adults had a TBSE in the past year (Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimatesa of the percentage of U.S. adults who ever or recently (in the past year) had a total body skin examination by skin cancer risk classification, NHIS 2010b.

| % | Total (persons) | % Ever having a TBSE | Number ever having a TBSE | % having a TBSE in past year | Number having a TBSE in past year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk population | 51.1 | 104,671,157 | 24.0 | 25,286,947 | 11.3 | 11,988,052 |

| Family history of skin cancer | 6.5 | 13,306,704 | 37.0 | 4,923,300 | 16.0 | 2,132,244 |

| One sunburn in past year | 16.5 | 33,849,141 | 19.8 | 6,698,830 | 8.8 | 2,985,993 |

| ≥2 sunburns in past year | 17.9 | 36,619,243 | 18.6 | 6,821,600 | 8.2 | 3,002,261 |

| White, non-Hispanic >65 years | 10.2 | 20,896,069 | 32.7 | 6,843,217 | 18.5 | 3,867,554 |

| Medium-riskc | 24.0 | 49,202,288 | 24.2 | 11,915,321 | 9.5 | 4,689,305 |

| Low-riskd | 24.9 | 50,956,915 | 8.3 | 4,227,909 | 3.4 | 1,733,338 |

TBSE: total body skin examination.

These data have been weighted to represent the U.S. population using hierarchical risk factors so each group is mutually exclusive.

High-risk group for developing skin cancer is defined by the USPSTF statement guidance, but this high-risk population definition excludes atypical moles or more than 50 moles as data are not available.

Medium-risk group defined as remainder of White non-Hispanic population.

Low-risk group consists of the remaining population (mostly non-White populations) who are at much lower risk of developing skin cancer.

Discussion

Between 2000 and 2010, there was a significant increase in ever having a TBSE among U.S. adults nationally from 1 in 7 (2000) to 1 in 6 (2005) to 1 in 5 (2010) U.S. adults (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1A). However, rates of ever having a TBSE either did not increase or remained stable in 2005 and 2010 compared to 2000 among Blacks, Asians, and AI/AN (Fig. 1B). Lifetime TBSE rates in 2010 were higher among three groups of U.S. adults at high-risk for skin cancer, specifically, fair-skinned men and women aged >65 years, adults reporting more sunburns, and individuals with a family history of skin cancer. Yet, three out of four high-risk individuals, who may be most likely to develop skin cancer, never had a TBSE (Table 3). Among high-risk groups, those with a family history of skin cancer followed by White, non-Hispanics >65 years were most likely to report and individuals reporting ≥2 sunburns were least likely to report ever having a TBSE.

Fig. 1.

A: Weighted percentage of U.S. adults who reported ever having a total body skin examination (TBSE) to screen for skin cancer overall and by age, and year, National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) 2000, 2005, and 2010. B: Weighted percentage of U.S. adults who reported ever having a total body skin examination (TBSE) to screen for skin cancer by gender, and race/ethnicity, and year, National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) 2000, 2005, and 2010.

At present, the USPSTF states that it is unclear whether benefits of routine TBSEs outweigh harms and also whether screening is beneficial for high-risk populations (USPSTF, 2001; Wolff et al., 2009). Potential harms of TBSE screening include: overdiagnosis via the detection of biologically benign disease that would otherwise go undetected, misdiagnosis of a benign lesion as malignant, complications of diagnostic or treatment interventions (including surgery), the psychological effects of being labeled with a potentially fatal disease, and the discomfort of a bare skin total body exam.

However, in 2012, the USPSTF did recommend that primary care physicians should counsel their fair-skinned patients aged 10–24 years on sun-protective behaviors and decreasing indoor tanning (USPSTF, 2012). Enhancing primary prevention strategies, such as targeted education, may be important during this period of uncertainty on screening guidelines (Andreeva and Cockburn, 2011).

The strengths of this study are related to its use of NHIS, which has a high response rate, sample diversity, the ability to provide estimates that are nationally representative, a large sample size, and experienced survey administrators. Limitations of this study include: self-reported responses that were subject to recall bias, responses that were not verified with medical records, use of a cancer module that is conducted every five years, and challenges with population estimates. Additionally, since this is a cross-sectional analysis, causal relationships cannot be determined.

Conclusions

Our study results show that TBSE rates have been increasing since 2000 both overall and among high-risk groups in spite of years of inconclusive and inconsistent evidence on routine screening via TBSEs and as a result less public education on skin cancer prevention and screening. Despite the increases, the incidence and mortality of melanoma have been rising during that timeframe. The increase in incidence may be due to increased diagnosis of melanomas as a result of more screening, however, this phenomenon does not explain the rise in mortality and warrants further investigation. Analyzing patterns among those who have received TBSEs highlights groups who have lower TBSE rates and who may benefit most from skin cancer prevention education. Among high-risk groups, these included individuals reporting one or more sun-burn(s). Additionally, fair-skinned young adults, those with no health insurance, and those reporting not having a primary care physician may also need to be targeted as at-risk groups since they reported relatively lower TBSE usage in 2010 compared to their opposing counterparts (Table 1). Gaps in current skin cancer screening research include: demonstrating a mortality benefit, identifying populations that would benefit from routine screening, understanding which screening methods should be promoted, and calculating the financial and social impact of skin cancer. In this current setting, data from our study may help plan future skin cancer prevention strategies, especially among high-risk and at-risk groups.

Acknowledgments

Funding/support: This study does not have any sponsors.

Appendix 1. Skin cancer screening and counseling guidelines

| U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (USPSTF, 2012; Wolff et al., 2009)

|

American Cancer Society (ACS) (ACS, 2013)

|

American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) (AAD, 2013; Koh et al., 1996)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009, 2012 | 2013 | Since 1985 | |

| When to start screening | Not addressed. | Adults aged ≥20 years during a periodic health check-up. | Not addressed. |

| Screening method & intervals | Not addressed | Not addressed | Not addressed |

| Patient skin self-examination | Insufficient evidence. (I statement) | Not addressed. | Recommended annually. |

| Total-body skin examination (TBSE) performed by a physician | Insufficient evidence. (I statement) | Not addressed. | Program endorses TBSE by a dermatologist for the general population. |

| High risk (not average risk) | Clinicians should be aware that fair-skinned men and women >65 years, patients with atypical moles, and those with >50 moles constitute known groups at substantially increased risk for melanoma. Other risk factors for skin cancer include: family history of skin cancer and a past history of considerable sun exposure and sunburns. Benefits from screening are uncertain, even in high-risk patients. | Not addressed. | Not addressed. |

| Behavioral counseling | Children, adolescents, and young adults aged 10 to 24 years who have fair skin, should be counseled on minimizing their exposure to ultraviolet radiation to reduce risk for skin cancer (B statement). For adults ≥25 years, insufficient evidence. (I statement) | At a periodic health checkup, adults ≥20 years should receive examination of the skin and health counseling about sun exposure. | Recommended. |

| When to stop screening | Not addressed. | Not addressed. | Not addressed. |

| Family history tool for patient self-assessment | My Family Health Portrait, a tool by the Surgeon General. |

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: None reported for all authors: Lakhani, Saraiya, Thompson, Coleman King, and Guy.

All financial interests (including pharmaceutical and device products): None reported by all authors: Lakhani, Saraiya, Thompson, Coleman King, and Guy.

Other disclosure: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Uncited references

Author contributions:

Drs. Lakhani, Saraiya, Coleman King, and Guy, and Mr. Thompson had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Lakhani, Saraiya, Thompson, Coleman King, and Guy.

Acquisition of data: Lakhani, Saraiya, Thompson, and Guy.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Lakhani, Saraiya, Thompson, Coleman King, and Guy.

Drafting of the manuscript: Lakhani, Saraiya, Thompson, Coleman King, and Guy.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Lakhani, Saraiya, Thompson, Coleman King, and Guy.

Statistical analysis: Lakhani, Saraiya, Thompson, and Guy.

Obtained funding: Not applicable.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Obtained funding: Lakhani, Saraiya, Thompson, Coleman King, and Guy.

Study supervision: Lakhani, Saraiya, and Thompson.

Contributor Information

Naheed A. Lakhani, Email: Naheeda786@gmail.com.

Trevor D. Thompson, Email: tkt2@cdc.gov.

Sallyann Coleman King, Email: fjq9@cdc.gov.

Gery P. Guy, Jr, Email: irm2@cdc.gov.

References

- AAD. American Academy of Dermatology, Melanoma Monday; 2012. http://www.aad.org/spot-skin-cancer/what-we-do/melanoma-monday/ [Google Scholar]

- ACOG. Skin cancer prevention, Tool Kit for Teen Care. 2. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, Youl P, English D. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer (Journal international du cancer) 2010;126:450–458. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva VA, Cockburn MG. Cutaneous melanoma and other skin cancer screening among Hispanics in the United States: a review of the evidence, disparities, and need for expanding the intervention and research agendas. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:743–745. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coups EJ, Geller AC, Weinstock MA, Heckman CJ, Manne SL. Prevalence and correlates of skin cancer screening among middle-aged and older white adults in the United States. Am J Med. 2010;123:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwueme DU, Guy GP, Jr, Li C, Rim SH, Parelkar P, Chen SC. The health burden and economic costs of cutaneous melanoma mortality by race/ethnicity—United States, 2000 to 2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:S133–S143. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MS, Doucette JT, Lim HW, Spencer J, Carucci JA, Rigel DS. Risk factors for presumptive melanoma in skin cancer screening: American Academy of Dermatology National Melanoma/Skin Cancer Screening Program experience 2001–2005. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy GP, Ekwueme DU. Years of potential life lost and indirect costs of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer: a systematic review of the literature. PharmacoEconomics. 2011;29:863–874. doi: 10.2165/11589300-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy GP, Jr, Ekwueme DU, Tangka FK, Richardson LC. Melanoma treatment costs: a systematic review of the literature, 1990–2011. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: Apr, 2012. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/, based on November 2011 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected US population. Healthy People 2010 Statistical Notes: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. pp. 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh HK, Norton LA, Geller AC, et al. Evaluation of the American Academy of Dermatology's National Skin Cancer Early Detection and Screening Program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:971–978. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis DJ, Halpern AC, Rebbeck T, et al. Validation of a melanoma prognostic model. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1597–1601. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.12.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCI. Skin Cancer. National Cancer Institute; American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures; 2013. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/skin. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283–287. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2008 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- USCS. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2009 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; Atlanta: 2013. Available at: www.cdc.gov/uscs. [Google Scholar]

- USPSTF. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: screening for skin cancer: recommendations and rationale. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:44–46. [Google Scholar]

- USPSTF. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: recommendation statement. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff T, Tai E, Miller T. Screening for skin cancer: an update of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:194–198. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]