Abstract

SHIP1 is at the nexus of intracellular signaling pathways in immune cells that mediate BM graft rejection, production of inflammatory and immunosuppressive cytokines, immunoregulatory cell formation, the BM niche that supports development of the immune system and immune cancers. Here I summarize how SHIP participates in normal immune physiology and the pathologies that result when SHIP is mutated. I also put forward a proposal that SHIP can have either inhibitory and activating roles in cell signaling that are determined by whether signaling pathways distal to PI3K are promoted by SHIP's substrate (PI(3,4,5)P3) or its product (PI(3,4)P2) I also propose the “Two PIP Hypothesis” that postulates both SHIP's product and its substrate are necessary for a cancer cell to achieve and sustain a malignant state. Finally, due to the recent discovery of small molecule antagonists and agonists for SHIP, I discuss potential therapeutic settings where chemical modulation of SHIP might be of benefit.

Keywords: SHIP; PI(3,4,5)P3; PI(3,4)P2; Treg cells; NK cells; MIR cells; antigen presentation; osteoblasts; s-SHIP; cancer; Crohn's Disease

SHIP Biochemistry

SHIP is a 5′ inositol poly-phosphatase that requires a PO4 group on the D3 position of the inositol ring for recognition of its two substrates.(1-3) As a consequence of this, SHIP's enzymatic activity is restricted to two different phosphoinositides, PI(3,4,5)P3 and I(1,3,4,5)P4, which SHIP converts to PI(3,4)P2 and I(1,3,4)P3, respectively.(Fig. 1) Production of both SHIP substrates is dependent on the 3′-lipid kinase activity of PI3K. Class I PI3Ks are the most thoroughly studied in mammalian cells and are composed of four isoenzymes subdivided in class IA (p110 α, β, γ, δ) and class IB (p110γ), which pair with five (p85α, p50α, p55α, p85β, and p55γ) and two (p101 and p84) regulatory subunits, respectively. p110α and p110β are ubiquitously expressed, whereas p110γ and p110δ are mainly expressed in leukocytes.(4) The formation of I(1,3,4,5)P4 occurs via phosphorylation of I(1,4,5)P3 by inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate 3-kinases (IP3K)(5) with the activity of phospholipases (e.g., PLC-γ) required to generate the IP3K substrate, I(1,4,5)P3, from PI(4,5)P2. By reducing the levels of PI(3,4,5)P3 and I(1,3,4,5)P4 in cells, SHIP is generally regarded as opposing the activity of PI3K to limit its activation of downstream effectors like Akt/PKB that can be recruited to PI(3,4,5)P3. In many instances this may be the case. However, PI(3,4)P2 also has a prominent positive signaling role in cells (6-10) and thus, in certain contexts, SHIP may also amplify PI3K signals (10) or trigger qualitatively different PI3K effector pathways than those promoted solely by PI(3,4,5)P3.(8,9) Rather than only hydrolyzing I(1,3,4,5)P4, SHIP may also limit I(1,3,4,5)P4 production, as I(1,3,4,5)P4 synthesis by IP3K requires I(1,4,5)P3 that is generated following activation of PLC-γ by Tec family kinases (e.g., Btk), whose activation is dependent upon the SHIP substrate PI(3,4,5)P3.(11) The enzymatic functions of SHIP are likely pivotal for most of its effects on normal physiology. However, there are instances in which a masking function of SHIP via its SH2 domain plays a pivotal role in cell signaling.(12, 13)

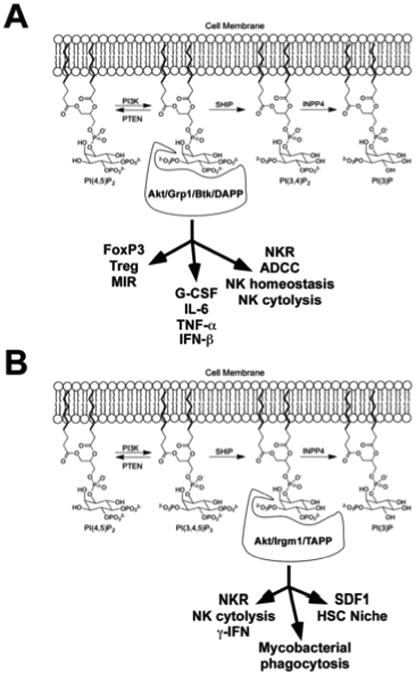

Fig. 1. Enzymatic generation and hydrolysis of PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 at the plasma membrane by PI3K, PTEN, SHIP and INPP4.

Determinants of SHIP signaling

The first determinant of whether SHIP can play a role in cell signaling is whether the cell expresses SHIP and at what level. SHIP was initially thought to be expressed ubiquitously in the hematopoietic compartment, (1-3, 14) although we found differential expression in B lineage cell lines.(15) We now appreciate that although SHIP is expressed in all hematopoietic cell lineages, including stem cells, (16) there is differential control of SHIP expression in certain blood cell lineages.(17) Control of SHIP expression within these blood cell lineages, and particularly the myeloid and NK cell lineages, contributes significantly to the differential function of cell subsets within each of these lineages.(18, 19) Studies to date indicate differential expression of SHIP protein can be achieved by regulation at multiple levels of gene expression that include induction of its transcription by SMAD family transcription factors, (20, 21) post-transcriptional control by microRNA species (22) and post-translational control via ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation.(23) Another additional post-translational determinant of SHIP expression, and therefore its enzymatic activity, is its specific truncation at the C-terminus.(24) This truncation may, in certain signaling contexts, prevent SHIP from hydrolyzing PI(3,4,5)P3 as these truncated isoforms are not recruited by adapter proteins that bind to SHIP's polyproline rich regions located in its COOH terminal region.(25) There is also developmental control of SHIP transcription as a stem cell specific SHIP isoform, s-SHIP, whose expression arises from an intronic promoter, demonstrates expression that is restricted to embryonic stem (ES) cells as well as fetal and adult hematopoietic stem cells (HSC).(16) Transgenesis of a GFP reporter under the control of the s-SHIP intronic promoter indicated possible s-SHIP expression in mammary stem cells (MaSC), although endogenous s-SHIP expression was not demonstrated in MaSC.(26) Thus, control of SHIP expression in a developmental fashion, or in response to cellular stimuli, is a major determinant of whether SHIP plays a role in cell signaling. This control occurs at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional and/or post-translational level.

The second determinant of SHIP signaling is differential recruitment from the cytosol to sites of signaling at the plasma membrane. Plasma membrane recruitment is thought to be critical for SHIP to influence cell signaling, since its primary substrate, PI(3,4,5)P3, is restricted to the plasma membrane and particularly at sites where PI3K is active. Consistent with this, SHIP is thought to be enzymatically active even while present in the cytosol(27) and thus recruitment determines when and where SHIP will act in cell signaling. Although it merits mention that SHIP can also hydrolyze I(1,3,4,5)P4.(1-3) I(1,3,4,5)P4 is a soluble phosphoinositide that plays an important role in Ca++ signaling in lymphocytes.(28) Control of SHIP recruitment to the plasma membrane is complex and can occur in association with adapter proteins (e.g., Shc, Grb2, Dok3), scaffold proteins (e.g., Gab1, 2) or following direct association of SHIP with receptor chains via its SH2 domain.(2, 16, 29-36). The latter includes growth factor receptors (2, 30-34, 37) or immune receptors such as FcRγIIb, FcγRIII, Ly49A-C, KLRG1, DAP10, DAP12 and 2B4.(38-43) These interactions, and thus recruitment of SHIP, in many cases require tyrosine phosphorylation of SHIP or signaling partners to which SHIP is recruited. In the latter context, SHIP can bind to a plasma membrane associated signaling protein via its SH2 domain while in the former situation the plasma membrane localized protein binds to SHIP via its PTB domain interacting with phosphorylated NPXY motifs in SHIP.(44, 45) In some cases the interaction is bidentate as occurs with recruitment of SHIP to receptor complexes via the adapter Shc. In this situation, Shc binds to phosphorylated SHIP via its PTB domain and SHIP binds phosphorylated Shc via its SH2 domain.(37, 46) The exception to this rule, is the stem cell specific SHIP isoform, s-SHIP, which unlike SHIP is not tyrosine phosphorylated upon cell stimulation, but is nonetheless recruited to the plasma membrane by Grb2 via interaction of proline rich sequences in the COOH terminal portion of SHIP with an SH3 domain in Grb2. Although the overwhelming body of evidence indicates SHIP exerts its role on cell signaling primarily via its enzymatic function, SHIP also appears to have a masking function as it can block recruitment of other key signaling enzymes as was first shown for SHP1 recruitment to 2B4 in NK cells.(12) In addition, SHIP has been shown to block PI3K activity at immune activating receptors by preventing PI3K recruitment to DAP10 and 12.(13) This masking function increases the complexity of SHIP's role in cell signaling as it theoretically enables SHIP to either inhibit (13) or promote (12) signals downstream of immune receptors depending upon which signaling component it is competing with.

A third determinant of SHIP signaling appears to be allosteric activation of its enzyme activity. The Protein Kinase C family of proteins has been known for some time to possess a domain called C2(47) that enables their association with phosphatidylserine or inositol phospholipid species present in the plasma membrane.(48) C2 domains can also target lipid modifying enzymes to sites of signaling at the plasma membrane including lipid phosphatases, phospholipases and lipid kinases.(48) Ong et al showed that like other inositol phosphatases, SHIP also contains a C2 domain and moreover association of this domain with its product PI(3,4)P2 enhances its enzymatic activity due to an allosteric effect on SHIP.(49) Thus, the amount of SHIP activity present at the plasma membrane is not only governed by its expression and recruitment patterns in the cell, but also by access to its own product, PI(3,4)P2. The presence of this C2 domain suggests a feed-forward mechanism in the control of SHIP activity and further indicates the importance of PI(3,4)P2 in control of cell signaling. SHIP is recruited in different ways to receptor signaling complexes where it may, or may not, have ready access to PI(3,4)P2, and this may determine whether allosteric modulation by its product is a significant determinant of SHIP signaling for a given receptor complex. Unfortunately, biochemical tools to dissect this question are not yet available. In addition to its own product increasing SHIP's enzymatic activity, a recent report has shown that phosphorylation of SHIP on serine by cAMP-responsive PKA can also increase SHIP's catalytic activity.(50) This presumably also occurs via allosteric effects as PKA mediated phosphorylation of purified recombinant SHIP increased its enzymatic activity in vitro. Thus, serine phosphorylation by PKAs, and perhaps other serine/threonine kinases, can also be a potential determinant of total SHIP activity at signaling complexes in the cell.

SHIP and hematopoietic stem cell function

HSC give rise to all lineages of the immune system and thus it is appropriate to first consider the role that SHIP and its isoforms play in HSC function. The SH2 containing isoforms of SHIP have been shown to be recruited to a multitude of cytokine and growth factor receptors (51, 52) many of which play a prominent role in HSC biology, and thus it was logical to assume that SHIP might play a role in HSC signaling and thus HSC homeostasis, homing and reconstituting potential. Indeed, both we and Helgason et al found that whole BM isolated from germline SHIP-/- donors exhibited a defect in reconstituting potential.(53, 54) Direct competition assays with purified HSC confirmed the competitive repopulation unit (CRU) assay findings of both groups and suggested that SHIP expression was an intrinsic requirement for HSC function.(54) However, when HSC were rendered deficient for all SH2 containing SHIP isoforms in SHIP+/+ hosts, homeostasis, long-term reconstitution and self-renewal capacity by SHIP-/- HSC were not disrupted.(55) These results indicated SHIP plays a cell extrinsic role in HSC function and implicated a role for SHIP in the niche that supports HSC quiescence. We provided direct evidence for this by showing that both primary BM stromal cells and osteoblasts (OB) express SHIP protein.(55) Moreover, SHIP is tyrosine phoshorylated in niche cells indicating it participates in cell signaling pathways active in niche cells. These findings are the first to demonstrate SHIP expression and participation in the function of non-hematopoietic cells. Consistent with SHIP playing an active role in OB cell signaling, the OB compartment in SHIP-/- mice exhibits altered growth characteristics and an immature phenotype (55) consistent with the increased cycling, spontaneous mobilization and compromised HSC function observed in germline SHIP-/- mice.(54) Disruption of BM niche function by SHIP-deficiency also includes profoundly diminished SDF1/CXCL12 expression in the BM of SHIP-deficient mice, (55) as well as in peripheral lymphoid tissues like spleen (Fig. 2). OB also play a prominent role in development of B lymphoid cells (56) and early B cell development is partially impaired in SHIP-/- mice.(57, 58) Thus, it will be important to determine if OB perturbations in SHIP-/- mice also contribute to inefficient B lymphopoiesis in SHIP-/- mice. This is a distinct possibility as Coggeshall and colleagues have indicated over-production of IL6 by other cells disrupts B lymphopoiesis in SHIP-/- mice by skewing hematopoiesis toward myelopoiesis.(59, 60) In addition, we have also documented profoundly increased G-CSF production in SHIP-/- mice, a growth factor that potently supports myelopoiesis.(55) Inappropriately high G-CSF levels may also contribute to myeloid skewing of hematopoiesis in SHIP-/- mice. Potentially OB are responsible for over-production of several growth factors and cytokines in SHIP-/- mice.

Fig. 2. SDF1/CXCL12 expression is profoundly diminished in the spleen of SHIP-/- mice.

Representative photomicrographs at of frozen sections prepared from the spleens of adult SHIP+/+ (A) and SHIP-/- mice (B) that were stained with biotinylated anti-SDF1 Ab (MAB350, R&D Systems) (A, B) or a biotinylated IgG1k control antibody (C) (MOPC-31C, Becton Dickinson). Staining by the anti-SDF1 Ab or the IgG1k control Ab was revealed by a secondary stain consisting of SA-AlexaFluor 546 (Molecular Probes) (red color). The blue stain is specific for IgD and reveals B lymphocyte areas in the spleen. The above procedures were performed and the resulting photomicrographs obtained by Dr. Katrin Moser (Deutsches Rheuma-Forschungszentrum, Berlin).

In addition to the role of the SH2-containing isoforms on HSC biology via their signaling role in bone marrow (BM) niche cells, we have also identified a stem cell specific isoform, s-SHIP, in both fetal and adult HSC. s-SHIP lacks an SH2 domain present in all other SHIP isoforms due to initiation of its transcription at an internal promoter between exons 5 and 6.(16) Expression of s-SHIP is restricted to ES cells and HSC as we are unable to detect its expression by RT-PCR in differentiated erythroid, lymphoid or myeloid cells isolated from fetal or adult mice. s-SHIP's highly restricted expression pattern and its recruitment to receptor components like gp130 in pluripotent stem cells suggests a cell autonomous role for s-SHIP in stem cells.(61) Intriguingly, unlike its SH2-containing counterparts, s-SHIP is not tyrosine phosphorylated in primitive stem cells and is recruited constitutively to the plasma membrane.(16) Thus, s-SHIP is uniquely positioned to influence PI3K signals in primitive stem cells, and possibly even while they are in a quiescent state.

SHIP in B Cell function

As mentioned above, there are B-lineage extrinsic effects of SHIP deficiency that may reduce the efficiency of B cell development in the bone marrow.(59, 60) Consistent with these studies our analysis of SHIP-deficient HSC in a SHIP-competent microenvironment showed normal production of peripheral B cell numbers as compared to WT competitor BM cells demonstrating SHIP is dispensable for B cell development.(55) However, other studies that preceded the above studies have found alterations of B cell function and humoral immunity in SHIP-/- mice.(57, 58, 62) In general humoral immunity to complex protein antigens appears to be intact; (58) however, certain IgG isotypes are more prominent in secreted antibody to vaccinated antigens in SHIP-/- hosts.(57) T-independent antibody responses are also enhanced in SHIP-/- deficient hosts. It is difficult from these studies to assign a definitive role to SHIP in B cell signaling as some or all of the effects on humoral immunity could be a consequence of profound alterations in T cell immunity, APC function and myeloid biology that occur in germline SHIP-/- mice. However, the above groups found that FcRγIIB inhibitory signals are compromised in SHIP-/- B cells, verifying earlier findings in B cell tumor lines that SHIP, rather than SHP1, is the inhibitory phosphatase recruited to FcγRIIB in B cells that inhibits B cell activation by immune complexes.(38, 63) It merits mention that the Iptkb kinase which phosphorylates I(1,4,5)P3 to generate I(1,3,4,5)P4 has been shown to be critical for control of store-regulated Ca++ channels and thus B cell anergy and activation.(28, 64, 65) Whether SHIP regulates intracellular Ca++ levels in B cells by hydrolysis of Iptkb-produced I(1,3,4,5)P4 is a possibility that might be examined as SHIP has been shown to also regulate Ca++ release following B cell activation.(63)

SHIP in NK cell biology

Our genetic analysis demonstrated that SHIP plays a prominent role in NK cell physiology via its participation in signaling pathways that control survival, homeostasis and repertoire diversity in the peripheral NK compartment.(40, 66, 67) Thus, SHIP deficiency results in severe NK repertoire disruptions that compromise the function of the NK compartment as evidenced by compromised NK-mediated rejection of MHC-I mismatched BM grafts in lethally irradiated SHIP-/- hosts.(40, 66, 68) Other groups have also begun to observe that SHIP plays a pivotal role in signaling pathways that control human NK cell function in vitro, including inhibition of FcγRIII signaling such that ADCC is enhanced when SHIP function is blocked in a human NK cell line (39) and also γ-IFN production by human NK subsets in response to IL-12 plus IL-18.(19) Although SHIP1 has not been directly linked to KIR signaling in NK cells, others have found that antibody cross-linking of an endogenously expressed KIR in the NK3.3 cell line triggers activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway.(69) Because SHIP can oppose PI3K-mediated activation of Akt and is recruited to the KIR analogs expressed by murine NK cells, (40) we proposed that human SHIP1 may also oppose PI3K/Akt signals at KIR in human NK cells.(40) In fact, because the Ig superfamily KIR receptors have greater affinity for their HLA ligands than the C-type lectin Ly49 receptors there could be a more prominent role for SHIP in human KIR signaling and NK cell biology. Combined KIR and human HLA transgenic mouse models are under development to test this possibility.

SHIP is recruited to a variety of NK inhibitory receptors (40, 41, 70, 71) and thus has the capacity to oppose or alter PI3K signals that influence cell survival, proliferation or gene expression in NK cells. We have recently identified a critical role for SHIP in 2B4/CD244 signaling in NK cells such that the absence of SHIP expression leads to increased expression of both 2B4/CD244 and SHP1 and inappropriately high recruitment of SHP1 to 2B4 subsequently compromising NK cytolysis via NKG2D and Ly49H.(12, 66, 72) This occurs in C57BL6 mice on an H2b background. Intriguingly, when the SHIP mutation is transferred to an H2d homozygous background, 2B4 expression is still dysregulated; however, cytolysis triggered by NKG2D is not compromised and in fact was substantially enhanced for MHC mismatched RMA targets.(72) One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that Ly49A, a potent NK licensing or educating receptor, (73, 74) is expressed at inappropriately high levels on SHIP-/- H2d NK cells.(72) In SHIP+/+ NK cells the Ly49A receptor is down-regulated in the presence of H2d ligands.(75) Perhaps SHIP-deficiency allows H2d+ NK cells to express the poly-specific MHC-I receptor Ly49A at sufficient levels to enable NK licensing or education of a greater proportion of NK cells; thus, increasing the lytic capacity of the SHIP-/- NK compartment for MHC-I mismatched tumor targets. In addition, we find that H2d haplotype SHIP-/- mice die with greater frequency and earlier onset than their H2b counterparts suggesting the possibility that SHIP is required to maintain NK self-tolerance when a higher affinity MHC-I receptor/ligand pair is present in the genome.

One deficiency that we observe uniformly in SHIP-deficient NK cells, regardless of MHC haplotype or 2B4 genotype, is impaired induction of γ-IFN after engagement of activating NK receptors, including NK1.1, NKG2D and NKp46.(72) In fact, γ-IFN induction is compromised even in H2d haplotype SHIP-/- NK cells despite their normal or enhanced cytolytic function. The discordant capacity for these two key NK functions in H2d+ SHIP-/- NK cells suggests that SHIP plays distinctly different signaling roles in control of cytolytic function and γ-IFN production. That SHIP is required for γ-IFN induction indicates a positive role for SHIP signaling in promoting this NK effector function. This positive signaling role for SHIP may be related to its production of PI(3,4)P2 and hence activation of distal effector kinases selectively recruited by PI(3,4)P2 that in turn promote induction of γ-IFN

SHIP and antigen presentation

Dendritic cells (DC) or professional antigen presenting cells (APC) play a central role in promoting adaptive immunity. Two different groups have analyzed APC function in SHIP-/- mice in some detail.(40, 68, 76-78) Using different approaches both groups find that priming of allogeneic T cell responses is profoundly compromised in SHIP-/- deficient mice consistent with the earlier findings of Wang et al that the incidence and severity of GvHD is reduced in SHIP-deficient hosts.(40) Host APC function is required for efficient priming of lethal GVHD.(79) However, these groups differ in their proposed mechanism to account for this defect. Ghansah et al were unable to find a defect in priming of allogeneic T cell responses when SHIP-/- DC were FACS purified from secondary lymphoid tissues, while whole splenocytes and lymph node (LN) cells from SHIP-/- DC mice showed compromised priming of allogeneic T cells.(68) In fact, they found that both splenic and LN DC numbers were significantly increased in SHIP-/- mice and showed comparable or even enhanced ability to prime γ-IFN production and proliferation by naïve, antigen-specific OT-II and OT-I transgenic T cells.(68) However, they found that Mac1+Gr1+ myeloid immunoregulatory (MIR) cells, which are profoundly increased in SHIP-/- mice, interfered with the ability of bona fide DC to prime MHC-mismatched T cells. They proposed then that the allogeneic T cell priming defect in SHIP-/- mice is due to a DC extrinsic effect of SHIP-deficiency.(68, 76) Helgason and colleagues prepared SHIP-/- DC by ex vivo differentiation from BM progenitor cells and concluded that the T cell priming defect is due to an intrinsic requirement for SHIP expression by DC.(77) To analyze DC function in vivo, Antignano et al immunized SHIP-/- and WT mice with either Ova/CFA or Ova/Alum. Consistent with our earlier findings, they saw no defect in SHIP-/- APC priming of antigen specific T cell responses when mice were immunized with ovalbumin in alum; however, they did note a defect with ovalbumin in CFA suggesting that priming of TH1 responses are selectively compromised with SHIP-/- DC.(78) As with the Helgason et al this study also relied on the use of ex vivo differentiated BM derived SHIP-/- and WT DC and not bona fide DC prepared from secondary lymphoid tissues as in the study of Ghansah et al. Ultimately the resolution of whether SHIP-/- DC support normal or defective antigen-specific T cell responses will require more sophisticated analysis of T cell priming in vivo. Towards that end, recent preliminary findings indicate that SHIP-/- DC prime normal T cell responses against a viral antigen when SHIP-/- DC are exposed to Ag ex vivo and then injected into naïve mice (E. Lind, W. Kerr and P. Ohashi, unpublished data).

SHIP in T cell function

The first evidence that SHIP plays a specific role in T cell signaling came from studies of transformed T cells and demonstrated tyrosine phosphorylation of SHIP and its association with the adapter Shc in response to T cell receptor (TcR) engagement.(37) Subsequently, others showed SHIP limits PI(3,4,5)P3 levels in T cells, (80) limits activation of Tec family kinases in T cells, (81) is recruited to the KLRG1 inhibitory receptor to oppose TcR signaling, (82) is recruited to the TcR in a LAT:Dok2:Grb2 complex and may be required for Dok2 recruitment to the TcR.(83) These in vitro studies in transformed T cell lines implicated SHIP in TcR signaling and, moreover, suggested multiple molecular mechanisms by which SHIP could influence signals emanating from the TcR that can shape T cell development, maturation, self-tolerance and effector function in T lymphocytes.

To determine if SHIP actually contributes to T cell signaling in a physiologically relevant manner has required the in vivo examination of the T cell compartment in SHIP mutant mice.(84-86) Firstly, it is important to note that although SHIP has been proposed from the above studies to oppose activation of Akt by limiting PI(3,4,5)P3 levels and to limit TcR signals, no inappropriate T cell mediated autoimmunity or T cell neoplasm has thus far been demonstrated in four independently generated germline SHIP-/- strains, (40, 62, 87, 88) CD4Cre+SHIPflox/flox or CD8Cre+SHIPflox/flox mice. It could be argued that such neoplasms are not observed in germline SHIP-/- strains due to their substantially reduced lifespan; (68, 87) however, in the T cell conditional SHIP deletion strains the absence of T cell neoplasms was not observed despite a normal life span. Nor are T cell neoplasms found in primary and secondary hosts reconstituted with SHIP-deficient BM cells.(55) In fact, circulating T cells are found at normal or reduced numbers in SHIP-/- mice (84, 87), after BM reconstitution (55) and may even have a reduced ability to respond to antigen, (78) suggesting defective, rather than hyperactive, TcR signaling in SHIP-deficient T cells. In addition, although SHIP levels are reduced in one T cell cancer line (Jurkat), the majority of T cell cancer lines not only express SHIP, but it is found to be tyrosine phosphorylated and therefore actively involved in intracellular signaling. An exception to this trend appears to be T-ALL where most of these cancers express substantially reduced levels of SHIP.(89)

The analysis of the T cell compartment in vivo where SHIP's contribution to normal physiology and pathology is best examined has now begun to be dissected using various genetic models of SHIP-deficiency.(90) Kashiwada et al initially showed that CD4+CD25+ cells with elevated levels of FoxP3 RNA are increased in frequency in the spleens of SHIP-/- mice and have normal suppressive activity in vitro.(90) Subsequently, Collazo et al showed there was an absolute increase in Treg cells in both the spleen and peripheral LNs of SHIP-/- mice and that these cells have slightly elevated levels of FoxP3 protein and suppressive capacity comparable to that of SHIP-proficient CD4+CD25+ Treg cells on a per cell basis in vitro and in vivo.(84) Moreover, it was found that a subset of naive CD4+CD25+ T cells in the periphery inappropriately acquire FoxP3 expression and consequently have potent immunosuppressive capacity in vitro and in vivo. In aggregate then, the germline SHIP-/- mouse has increased T immunoregulatory capacity due to both mechanisms and consistent with this, rejection of vascularized cardiac grafts is delayed in adult mice after induction of SHIP-deficiency.(84) This increased T immunoregulatory capacity may combine forces with increased myeloid immunoregulatory capacity in SHIP-/- mice to enhance engraftment and reduce GVHD following allogeneic BMT as host Treg cells can promote both effects.(91) Locke et al subsequently confirmed these findings, but also found in vitro evidence that SHIP may promote T cell differentiation toward the TH17 lineage at the expense of Treg cell formation.(85) Evaluation of T cell effector responses in T cell conditionally mutant mice has revealed a direct role for SHIP in TH1, TH2 and CD8 T cell functions.(86) TH1 responses were normal or slightly enhanced, while TH2 responses were compromised based on reduced production of IL4, IL5 and IL13 and reduced responses to Helminth infection. Interestingly, CD8 T cells from CD4CreSHIPflox/flox mice exhibited more potent cytolytic responses suggesting that TH1 support of CD8 T cell responses is enhanced by SHIP-deficiency. Intriguingly, this group did not observe an increase in Treg cells suggesting that SHIP may not control FoxP3 acquisition and Treg cell homeostasis in a T-lineage intrinsic fashion. We recently found both inappropriate FoxP3 expression by naive CD4 T cells and expansion of Treg cell numbers in LysMCreSHIPflox/flox mice (Collazo, M., Paraiso, K. and Kerr, W.; unpublished data) that have ablation of SHIP expression only in myeloid lineage cells, indicating SHIP controls FoxP3 expression and Treg homeostasis lineage via a myeloid intermediate.

It has recently been discovered that SHIP-deficient mice exhibit a profound Crohn's-like ileitis – inflammation and destruction of the terminal portion of the small intestine.(92) Remarkably this pathology does not found extend into the remainder of the small, large intestine or bowel and thus appears to closely resemble human Crohn's Disease implying a precise role for SHIP in homeostasis at this key site of mucosal immunity. BM chimeras confirmed this was not due to an intrinsic defect in intestinal epithelial Paneth cells in the terminal ileum. In addition, the intestinal inflammation was transferred to irradiated WT hosts by reconstitution with SHIP-deficient splenocytes confirming the hematolymphoid origin of disease. Moreover, there is a rather profound deficit in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the small intestines of SHIP-deficient mice as well as neutrophilia. These latter findings suggest the autoimmune attack is not be mediated by T cells, but rather results from an over-response by SHIP-deficient neutrophils recruited to this site in the context of limiting numbers of effector CD4 and CD8 T cells.(92) Thus, the SHIP-deficient innate immune system over-responds and causes tissue damage subsequent to an inadequate adaptive immune defense at this mucosal site. It is an intriguing possibility that a similar maladapted response also occurs in mucosal tissues in the lungs of SHIP-/- mice.

SHIP in myeloid biology and function

Perhaps the most prominent impact of the SHIP mutation is on the myeloid compartment with myeloid cells greatly expanded in BM, spleen and LN of SHIP-/- mice. This myeloid expansion leads to consolidation of the lungs in both germline SHIP-/- mice (87) and adult mice following induction of genetic SHIP deficiency mice.(76) However, this myeloproliferative syndrome does not progress to myeloid leukemia, even after serial passage of SHIP-deficient BM stem/progenitors through primary and secondary hosts.(55) Intriguingly, LysMCre mice do not have a major myeloproliferative syndrome and in our hands have a normal lifespan suggesting that the cause of the myeloproliferative disease in germline SHIP-/- mice (D. Wood, W. Kerr, unpublished data) is due to inappropriate production of myelopoietic growth factors by microenvironment cells such as osteoblasts (OB). Consistent with this, SHIP is expressed by OB and SHIP-/- mice have a 400-500% increase in G-CSF levels and a defect in osteoblast maturation.(55)

SHIP plays a pivotal role in various myeloid effector functions and two studies indicate SHIP regulates, (93, 94) rather than promotes, phagocytosis mediated by Fcγreceptors (FcγR) or complement receptors (e.g., CR3). However, a recent study has found that SHIP, via generation of PI(3,4)P2, promotes recruitment of the GTPase Irgm1 to sites of phagocytosis, a critical step in maturation of the phagosome and particularly for engulfment of bacteria.(9) Several of these studies have also indicated a role for SHIP in limiting other macrophage effector functions, including production of the oxidative burst and inflammatory cytokines.(94) Although another study found a positive role for SHIP in the oxidative burst.(95) Thus, there appears to be conflicting findings concerning whether SHIP promotes or represses macrophage effector functions in the immune system.

Resolution of the role that SHIP plays in macrophage effector function will likely require further analysis of SHIP's role in these processes in vivo and possibly in mice with myeloid specific ablation of SHIP expression (e.g., LysMCreSHIPflox/flox mice).(88) Certainly this poses a formidable challenge, but if successful such studies would yield answers of physiological import. The studies to date have largely studied macrophage function ex vivo. It has been our general experience that SHIP-/- primary hematolymphoid cells cultured ex vivo have a survival advantage relative to their WT counterparts and thus are more likely to give higher readouts in assays of effector function. This creates a potential for erroneous findings of enhanced function with the SHIP-deficient cultures even after normalizing for viable cell numbers. One effector function for which there is both in vitro and in vivo evidence of increased effector function in mature myeloid cells is the osteoclast (OC) (96) – a tissue macrophage population that is responsible for bone remodeling via engulfment of bone forming osteolineage cells or OB. Recent evidence indicates this feature of SHIP signaling may not be mediated entirely by its enzymatic activity, as SHIP can mask a PI3K binding site in the DAP12 cytoplasmic tail that is also necessary for PI3K signaling by key OC activating receptors like TREM2.(13) Whether the osteoporetic phenotype of SHIP-/- mice is entirely dependent upon hyper-resorptive behavior by OC awaits the analysis of mice with conditional ablation of SHIP expression in the osteoblast lineage, as OB have recently been shown to express SHIP and exhibit altered growth when SHIP-deficient.(55)

SHIP has been found to be required for development of marginal zone (MZ) macrophages which is ointriguoing since most myeloid cells types are normal or expanded in SHIP-/- mice.(88) Because this was observed in LysMCrSHIPflox/flox mice we can conclude that SHIP signaling in myeloid lineage cells is required for development of MZ macrophages and results from over activation of the Tec kinase Btk, since Btk-/- SHIP-/- mice have normal numbers of MZ macrophages.(88) Another important function for SHIP in vivo in myeloid cells is endotoxin tolerance and this appears to be mediated primarily through macrophages and their production of TGF-β.(18) Sly et al showed that LPS (bacterial endotoxin) increases expression of SHIP in macrophages and mast cells. Elevation of SHIP expression suppresses IFN-beta production and subsequent deleterious immune responses.

Another important SHIP function is to limit the number of myeloid immunoregulatory (MIR) cells. Myeloid cells that suppress unusually vigorous immune responses, first identified by Bronte and colleagues, (97) are now referred to as M2 cells, alternative activated macrophages (AAM), immature dendritic cells, tolerogenic DC, immature myeloid cells, myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC), myeloid suppressor cells (MSC). This nomenclature diversity poses a challenge as it makes it difficult to determine if the same cell population is being studied by different groups.(98) MIR cells are a logical name as this clearly identifies these cells as immunoregulatory and is consistent with the T cell, (99, 100) NK cell (101) and now B cell fields(102) where the immunoregulatory term has been uniformly adopted. Coincidentally, MIR also means ‘peace’ in Russian and this is in line with the peace-keeping mission MIR cells play in normal physiology. We identified a strong requirement for SHIP expression to restrain the numbers of MIR cells present in secondary lymphoid tissues such as spleen and LN and showed that they have a potent capacity to suppress allogeneic T cell responses.(68, 76) This may contribute to the reduced incidence and severity of GvHD observed in SHIP-deficient BMT recipients, (40) although increased Treg cells numbers in SHIP-deficient hosts may also be a contributing factor.(84) Rauh et al subsequently showed that an analogous MIR cell population is also increased in the lungs of SHIP-/- mice.(103) Intriguingly, they identified TGF-β as being critical for induction of SHIP in WT myeloid cells and a subsequent study from the same group further implicated TGFβ as being responsible for inducing SHIP, and that SHIP in turn limits IFN-β production after viral infection. TGF-β induces SHIP expression via a SMAD dependent pathway (20) and this has been shown to occur via SMAD4 in macrophages.(21) This TGF–β/SMAD pathway could act in a feed-forward fashion to promote SHIP expression during intense immune challenges where endotoxin induction of SHIP expression alone is insufficient.

SHIP in innate immune cells

SHIP is also known to be expressed and participate in cell signaling in a wide variety of innate immune cells including neutrophils, (104) basophils, (105) mast cells (106, 107) and eosinophils.(108) The pulmonary consolidation and asthma-like syndrome (108) that occurs in SHIP-/- mice may in fact be due to dysfunction on the part of one or several of these innate immune cell types.(105, 106, 108) As discussed above, SHIP has an important role in signaling by innate immune receptors expressed by many of these cells that does not involve opposing PI3K signals at these receptors, but rather suppression of inflammatory cytokine production following SHIP induction by SMAD4.(18, 21, 109) SHIP is also expressed by platelets and cells of the megakaryocytic lineage and negatively influences their production in vivo.(110, 111) Although the primary function of platelets is in clotting and maintenance of hemostasis, platelets have recently been found to have an unexpected role in killing of P. falciparum present in infected erythrocytes.(112) SHIP inhibits glycoprotein VI (GPVI) mediated dense granule secretion and promotes PAR-mediated dense granule secretion by platelets.(113) Thus, whether SHIP also inhibits or promotes platelet-mediated killing of parasites present in erythrocytes seems a valid question.

Promoting/repressing immune functions

It has been well over a decade since SHIP was first cloned and proposed to be a major inhibitory phosphatase at receptors that recruit and activate PI3K enzymes. This view is still correct in many instances. However, we are beginning to appreciate that SHIP may also have a role in promoting certain immune functions. I propose that whether SHIP serves as a repressor or promoter of immune functions depends largely on the PIP species that is most critical for the intracellular signals that promote that specific immune function. For cellular functions where SHIP plays an inhibitory role, PI(3,4,5)P3 is likely to be the dominant inositol phospholipid species that selectively recruits distal effectors necessary for that function (Fig. 3A). Conversely, for cellular functions where SHIP is required, PI(3,4)P2 is likely the dominant inositol phospholipid promoting that activity via enhanced recruitment of distal effectors with preference for PI(3,4)P2 (Fig. 3B). Fig. 3 indicates immune functions that are likely to be dependent upon PI(3,4,5)P3 or PI(3,4)P2 generation based on whether SHIP-deficiency has a positive or negative effect on them, respectively. For immune functions that are PI(3,4)P2 biased, it will be interesting in the coming years to determine if the INPP4A/B genes also influence these functions as PI(3,4)P2 is the major target for these enzymes. In some instances, both PIPs may be utilized by the same receptor to trigger (PI(3,4,5)P3 biased signals) or sustain a cellular response (PI(3,4)P2 biased signals).

Fig. 3. Dual roles for SHIP in immunity are a consequence of PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 biased distal effectors.

(A) PI(3,4,5)P3 biased signaling components (Akt/Grp1/Tec kinases/DAPP) and the immune functions that SHIP can inhibit by reducing PI(3,4,5)P3 levels. (B) PI(3,4)P2 biased signaling components (Akt/Irgm1/TAPP) and the immune functions that SHIP can promote by production of PI(3,4)P2.

SHIP and cancer: the “two PIP hypothesis”

The PI3K/Akt pathway is strongly implicated in cancer as evidenced by the impact of gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in PI3K and loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in PTEN that promote cancer formation. Consequently, there has been a substantial effort to identify LOF mutations in SHIP based on the prevailing view that SHIP simply opposes PI3K mediated activation of Akt. However, only sporadic reports of SHIP LOF mutations have been observed with most occurring in myeloid leukemias.(114-117) Due to the infrequent nature of these mutations, it has not been possible to statistically establish a causative role for these mutations in blood cancer. In fact, one group who rigorously analyzed a similar AML cohort was unable to confirm a significant frequency of SHIP mutations in their Caucasian cohort.(118) To overcome this statistical hurdle, some have resorted to over-expressing the SHIP gene in SHIP null leukemia lines like K562 to demonstrate that this restores apoptosis to these lines. Setting aside concerns over enforced overexpression of a potent signaling molecule on cell viability, these studies support the notion that loss of SHIP promotes leukemogenesis. However, there have been different experiences with this approach, as one group found that restoration of SHIP expression in the K562 leukemia line did not decrease growth and survival of these cells.(119) Another group also found that reduction of SHIP expression does not positively impact multiple myeloma (MM) cell growth.(120) It also merits consideration that the Src family kinase Lyn, which is very effective at activating SHIP, is an oncogenic kinase in many leukemias, including Bcr-Abl+ and Flt3-ITD+ leukemias and their drug resistant forms.(121-123)

We considered then that SHIP1 may actually facilitate cancer cell survival rather than suppress it as PTEN does.(10) Consistent with this view, the enzymatic activities of these inositol phosphatases are quite distinct in that the 3′ poly-phosphatase activity of PTEN reverses the PI3K reaction to generate PI(4,5)P2 from PI(3,4,5)P3, while the 5′ poly-phosphatase activity of SHIP1/2 converts PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(3,4)P2. This distinction is crucial as it enables SHIP1/2 and PTEN to have distinctly different effects on Akt signaling. In fact, the PH domain of Akt binds with greater affinity to the SHIP1/2 product PI(3,4)P2 leading to more potent activation of Akt than the direct product of PI3K, PI(3,4,5)P3.(6) Thus, SHIP1, which is expressed by most blood cell malignancies, could actually promote growth and survival of neoplastic cells. Consistent with this hypothesis, PI(3,4)P2 levels are increased in leukemia cells (124) and increased levels of PI(3,4)P2 in INPP4A and INPP4B mutant mice promote cell transformation and tumorigenicity.(125,126) Thus, via generation of PI(3,4)P2, SHIP1/2 could in some contexts amplify survival or proliferative signals in neoplastic cells by providing additional docking sites at the plasma membrane for recruitment and activation of PH-domain containing kinases such as Akt. We refer to this as the “Two PIP Hypothesis” where a certain amount of both PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 is required to promote a malignant state (Fig. 3). Consistent with this hypothesis, we find that a SHIP1 selective inhibitor reduces Akt activation and promotes apoptosis of human blood cell cancers that express SHIP1.(10) We confirmed a role for PI(3,4)P2 in cancer signaling by showing that introduction of exogenous PI(3,4)P2 into leukemia cells protects them from SHIP1 inhibition in a dose-dependent manner.(10) Consistent with the ‘Two PIP Hypothesis’, a SHIP agonistic compound also reduces the growth of MM cells in vitro.(127) That both antagonistic and agonistic SHIP modulators can kill MM cells highlights the delicate balance of both PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 signals the cancer cell must achieve in order to achieve and sustain the malignant state. It is likely then that multiple configurations of PI3K, PTEN, SHIP1/2 and/or INPP4 mutations (or alterations in their expression), are permissible in order to increase levels of both PIP species to achieve this malignant state. It is important then to analyze the entire spectrum of key inositol phospholipid signaling enzymes (PI3K, PTEN, SHIP1/2, INPP4) in each blood cell malignancy, and solid tumors such as breast cancer, (128) in order to better understand how perturbations of this signaling cassette result in each particular cancer satisfying the ‘Two PIP Hypothesis’.

Chemical modulation of SHIP1 activity

Recent efforts by my group and that of Krystal and colleagues have resulted in small molecule approaches to inhibit or enhance the enzymatic activity of SHIP1.(10, 49) Based on the ‘Two PIP Hypothesis’ there are obvious applications for both SHIP antagonists and agonists in cancer treatment.(10, 127) In Wang et al we proposed that, “inhibition of SHIP signaling should be explored as a means to increase both the efficacy and utility of allogeneic BM transplantation.” (40) The realization of this idea might have significant clinical benefit in a wide variety of immunological diseases including severe autoimmune disease where BMT is used to reset the immune system and in BMT for blood cell cancers. Toward that end, we have found that treatment of mice with a SHIP inhibitor significantly expanded the MIR cell compartment and reduced mouse and human APC priming of allogeneic T cell responses.(10) As organ graft rejection is delayed in mice with induced genetic SHIP deficiency, (84) it may also be worth exploring whether SHIP inhibitors are of utility in solid organ transplantation, especially given SHIP's role in limiting immunoregulatory capacity in the T cell compartment in vivo.(84, 85)

The use of SHIP modulation in autoimmune diseases is also a distinct possibility, but here the path is less clear due to the inhibitory and activating roles of SHIP in different immune functions. As asthma like conditions prevail in SHIP-deficient mice this would seem to preclude the use of SHIP inhibitors in autoimmunity and other disease settings; however, the lung consolidation and myeloid cell infiltrate observed in all germline SHIP-/- mice is not observed in SHIP inhibitor treated mice.(10) Given its potent ability to martial immunoregulatory elements of both the myeloid and T lymphoid compartments it might then be plausible to use SHIP inhibitors in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. However, SHIP agonists might also find application in this setting.(49) Further research to examine these possibilities is needed.

Given our recent finding that in an MHC haplotype disparate setting SHIP-deficient NK cells exhibit profoundly increased cytolytic activity against MHC-mismatched tumors, (72) there may also be applications for SHIP inhibitors to increase the effectiveness of the NK cell mediated graft-versus-tumor effect identified by Velardi and colleagues in HLA mismatched BMT for cancer.(129) Other justifications for the use of SHIP inhibitors in cancer include the fact that they might boost the effectiveness of Ab therapies for cancer and could also reduce metastases. SHIP has been shown to inhibit signals emanating from the FcγRIII, (130) the major promoter of ADCC in both human and mouse NK cells. As many Ab therapies like Rituximab are thought to mediate their effects through ADCC, SHIP inhibitors could be combined with Ab therapies to increase their effectiveness. SHIP-deficient mice also exhibit severely diminished levels of SDF-1/CXCL12 production in secondary lymphoid tissues and BM where tumor metastases are lured by SDF-1/CXCL12. Hence, it stands to reason that SHIP inhibitors might also reduce tumor burden not only by directly promoting the death of cancer cells, but also by reducing their capacity to find safe harbors in microenvironments known to nurture metastases and cancer stem cells.

Fig. 4. The ‘Two PIP Hypothesis’ in Cancer.

Signals emanating from both PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 are necessary for the cancer cell to achieve and sustain the malignant state.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank former and current members of the Kerr lab whose hard work and dedication have helped to define the role that SHIP plays in immunity and cancer. I am also deeply indebted to the vibrant and insightful work of my fellow ‘SHIP-mates’ at other institutions. Due to space limitations I apologize for not being able to cite all their studies that could have also merited mention. I thank Michelle Collazo and Kim Paraiso for allowing me to cite our unpublished findings. During the course of our studies in this area my research was and continues to be supported by grants from the U.S. NIH (R01 HL72523, RO1 HL085580) and The Paige Arnold Butterfly Run. During the initial phases of his SHIP research the author was very fortunate to be the Newman Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and is currently the Murphy Family Professor of Childrens' Oncology Research and an Empire Scholar of SUNY Upstate Medical University.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The author currently serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of Aquinox Pharmaceuticals (Vancouver, BC) that is devoted to chemical modulation of SHIP1 expression for therapeutic purposes. The author is also the inventor or co-inventor on patents, both issued and pending, related to modulation of SHIP expression and activity for therapeutic purposes.

References

- 1.Kavanaugh WM, Pot DA, Chin SM, Deuter-Reinhard M, Jefferson AB, Norris FA, Masiarz FR, Cousens LS, Majerus PW, Williams LT. Multiple forms of an inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase form signaling complexes with Shc and Grb2. Current Biology. 1996;6:438–445. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00511-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damen JE, Liu L, Rosten P, Humphries RK, Jefferson AB, Majerus PW, Krystal G. The 145-kDa protein induced to associate with Shc by multiple cytokines is an inositol tetraphosphate and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate 5-phosphatase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:1689–1693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lioubin MN, Algate PA, Tsai S, Carlberg K, Aebersold A, Rohrschneider LR. p150Ship, a signal transduction molecule with inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase activity. Genes & Development. 1996;10:1084–1095. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkins PT, A K, Davidson K, Stephens LR. Signalling through Class I PI3Ks in mammalian cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34(Pt 5):647–662. doi: 10.1042/BST0340647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia HJ, Yang G. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinases: functions and regulations. Cell Res. 2005;15:83–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC, Toker A. Direct regulation of the Akt proto-oncogene product by phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate. Science. 1997;275:665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.665. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheid MP, Huber M, Damen JE, Hughes M, Kang V, Neilsen P, Prestwich GD, Krystal G, Duronio V. Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)P3 is essential but not sufficient for protein kinase B (PKB) activation; phosphatidylinositol (3,4)P2 is required for PKB phosphorylation at Ser-473: studies using cells from SH2-containing inositol-5-phosphatase knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9027–9035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106755200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma K, Cheung SM, Marshall AJ, Duronio V. PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 levels correlate with PKB/akt phosphorylation at Thr308 and Ser473, respectively; PI(3,4)P2 levels determine PKB activity. Cell Signal. 2008;20:684–694. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiwari S, Choi HP, Matsuzawa T, Pypaert M, MacMicking JD. Targeting of the GTPase Irgm1 to the phagosomal membrane via PtdIns(3,4)P(2) and PtdIns(3,4,5)P(3) promotes immunity to mycobacteria. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:907–917. doi: 10.1038/ni.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks R, Fuhler GM, Iyer S, Smith MJ, Park MY, Paraiso KH, Engelman RW, Kerr WG. SHIP1 inhibition increases immunoregulatory capacity and triggers apoptosis of hematopoietic cancer cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3582–3589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scharenberg AM, El-Hillal O, Fruman DA, Beitz LO, Li Z, Lin S, Gout I, Cantley LC, Rawlings DJ, Kinet JP. Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PtdIns-3,4,5-P3)/Tec kinase-dependent calcium signaling pathway: a target for SHIP-mediated inhibitory signals. EMBO Journal. 1998;17:1961–1972. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahle JA, Paraiso KH, Kendig RD, Lawrence HR, Chen L, Wu J, Kerr WG. Inappropriate Recruitment and Activity by the Src Homology Region 2 Domain-Containing Phosphatase 1 (SHP1) Is Responsible for Receptor Dominance in the SHIP-Deficient NK Cell. J Immunol. 2007;179:8009–8015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng Q, Malhotra S, Torchia JA, Kerr WG, Coggeshall KM, Humphrey MB. TREM2- and DAP12-dependent activation of PI3K requires DAP10 and is inhibited by SHIP1. Sci Signal. 3:ra38. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware MD, Rosten P, Damen JE, Liu L, Humphries RK, Krystal G. Cloning and characterization of human SHIP, the 145-kD inositol 5-phosphatase that associates with SHC after cytokine stimulation. Blood. 1996;88:2833–2840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerr WG, Heller M, Herzenberg LA. Analysis of lipopolysaccharide-response genes in B-lineage cells demonstrates that they can have differentiation stage-restricted expression and contain SH2 domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:3947–3952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tu Z, Ninos JM, Ma Z, Wang JW, Lemos MP, Desponts C, Ghansah T, Howson JM, Kerr WG. Embryonic and hematopoietic stem cells express a novel SH2-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase isoform that partners with the Grb2 adapter protein. Blood. 2001;98:2028–2038. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geier SJ, Algate PA, Carlberg K, Flowers D, Friedman C, Trask B, Rohrschneider LR. The human SHIP gene is differentially expressed in cell lineages of the bone marrow and blood. Blood. 1997;89:1876–1885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sly LM, Rauh MJ, Kalesnikoff J, Song CH, Krystal G. LPS-induced upregulation of SHIP is essential for endotoxin tolerance. Immunity. 2004;21:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trotta R, Parihar R, Yu J, Becknell B, Allard J, 2nd, Wen J, Ding W, Mao H, Tridandapani S, Carson WE, Caligiuri MA. Differential expression of SHIP1 in CD56bright and CD56dim NK cells provides a molecular basis for distinct functional responses to monokine costimulation. Blood. 2005;105:3011–3018. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valderrama-Carvajal H, Cocolakis E, Lacerte A, Lee EH, Krystal G, Ali S, Lebrun JJ. Activin/TGF-beta induce apoptosis through Smad-dependent expression of the lipid phosphatase SHIP. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:963–969. doi: 10.1038/ncb885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan H, Ding E, Hu M, Lagoo AS, Datto MB, Lagoo-Deenadayalan SA. SMAD4 is required for development of maximal endotoxin tolerance. J Immunol. 184:5502–5509. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Rao DS, Baltimore D. Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7113–7118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902636106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruschmann J, Ho V, Antignano F, Kuroda E, Lam V, Ibaraki M, Snyder K, Kim C, Flavell RA, Kawakami T, Sly L, Turhan AG, Krystal G. Tyrosine phosphorylation of SHIP promotes its proteasomal degradation. Exp Hematol. 38:392–402. 402 e391. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damen JE, Liu L, Ware MD, Ermolaeva M, Majerus PW, Krystal G. Multiple forms of the SH2-containing inositol phosphatase, SHIP, are generated by C-terminal truncation. Blood. 1998;92:1199–1205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Damen JE, Ware MD, Kalesnikoff J, Hughes MR, Krystal G. SHIP's C-terminus is essential for its hydrolysis of PIP3 and inhibition of mast cell degranulation. Blood. 2001;97:1343–1351. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohrschneider LR, Custodio JM, Anderson TA, Miller CP, Gu H. The intron 5/6 promoter region of the ship1 gene regulates expression in stem/progenitor cells of the mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2005;283:503–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phee H, Jacob A, Coggeshall KM. Enzymatic activity of the Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol phosphatase is regulated by a plasma membrane location. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19090–19097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller AT, Sandberg M, Huang YH, Young M, Sutton S, Sauer K, Cooke MP. Production of Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 mediated by the kinase Itpkb inhibits store-operated calcium channels and regulates B cell selection and activation. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:514–521. doi: 10.1038/ni1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Damen JE, Liu L, Wakao H, Miyajima A, Rosten P, Jefferson AB, Majerus PW, Krosl J, Humphries RK, Krystal G. The role of erythropoietin receptor tyrosine phosphorylation in erythropoietin-induced proliferation. Leukemia. 1997;11:423–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huber M, Helgason CD, Damen JE, Liu L, Humphries RK, Krystal G. The src homology 2-containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP) is the gatekeeper of mast cell degranulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:11330–11335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verdier F, Chretien S, Billat C, Gisselbrecht S, Lacombe C, Mayeux P. Erythropoietin induces the tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-2. An alternate pathway for erythropoietin-induced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:26173–26178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zamorano J, Keegan AD. Regulation of apoptosis by tyrosine-containing domains of IL-4R alpha: Y497 and Y713, but not the STAT6-docking tyrosines, signal protection from apoptosis. Journal of Immunology. 1998;161:859–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang S, Mantel C, Broxmeyer HE. Flt3 signaling involves tyrosyl-phosphorylation of SHP-2 and SHIP and their association with Grb2 and Shc in Baf3/Flt3 cells. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 1999;65:372–380. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drachman JG, Kaushansky K. Dissecting the thrombopoietin receptor: functional elements of the Mpl cytoplasmic domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:2350–2355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lemay S, Davidson D, Latour S, Veillette A. Dok-3, a novel adapter molecule involved in the negative regulation of immunoreceptor signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2743–2754. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2743-2754.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robson JD, Davidson D, Veillette A. Inhibition of the Jun N-terminal protein kinase pathway by SHIP-1, a lipid phosphatase that interacts with the adaptor molecule Dok-3. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2332–2343. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2332-2343.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamkin TD, Walk SF, Liu L, Damen JE, Krystal G, Ravichandran KS. Shc interaction with Src homology 2 domain containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP) in vivo requires the Shc-phosphotyrosine binding domain and two specific phosphotyrosines on SHIP. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:10396–10401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ono M, Bolland S, Tempst P, Ravetch JV. Role of the inositol phosphatase SHIP in negative regulation of the immune system by the receptor Fc(gamma)RIIB. Nature. 1996;383:263–266. doi: 10.1038/383263a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galandrini R, Tassi I, Mattia G, Lenti L, Piccoli M, Frati L, Santoni A. SH2-containing inostiol phosphatase SHIP-1 transiently translocates to raft domains and modulates CD16-mediated cytotoxicity in human NK cells. Blood. 2002 doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang JW, Howson JM, Ghansah T, Desponts C, Ninos JM, May SL, Nguyen KH, Toyama-Sorimachi N, Kerr WG. Influence of SHIP on the NK repertoire and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Science. 2002;295:2094–2097. doi: 10.1126/science.1068438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eissmann P, Beauchamp L, Wooters J, Tilton JC, Long EO, Watzl C. Molecular basis for positive and negative signaling by the natural killer cell receptor 2B4 (CD244) Blood. 2005 doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abramson J, Pecht I. Clustering the mast cell function-associated antigen (MAFA) leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of p62Dok and SHIP and affects RBL-2H3 cell cycle. Immunol Lett. 2002;82:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gays F, Aust JG, Reid DM, Falconer J, Toyama-Sorimachi N, Taylor PR, Brooks CG. Ly49B is expressed on multiple subpopulations of myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:5840–5851. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rohrschneider LR, Fuller JF, Wolf I, Liu Y, Lucas DM. Structure, function, and biology of SHIP proteins. Genes & Development. 2000;14:505–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krystal G. Lipid phosphatases in the immune system. Semin Immunol. 2000;12:397–403. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0222. In Process Citation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tridandapani S, Kelley T, Pradhan M, Cooney D, Justement LB, Coggeshall KM. Recruitment and phosphorylation of SH2-containing inositol phosphatase and Shc to the B-cell Fc gamma immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif peptide motif. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 1997;17:4305–4311. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newton AC. Protein kinase C. Seeing two domains. Curr Biol. 1995;5:973–976. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hurley JH, Meyer T. Subcellular targeting by membrane lipids. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:146–152. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ong CJ, Ming-Lum A, Nodwell M, Ghanipour A, Yang L, Williams DE, Kim J, Demirjian L, Qasimi P, Ruschmann J, Cao LP, Ma K, Chung SW, Duronio V, Andersen RJ, Krystal G, Mui AL. Small-molecule agonists of SHIP1 inhibit the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2007;110:1942–1949. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang J, Walk SF, Ravichandran KS, Garrison JC. Regulation of the Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase (SHIP1) by the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20070–20078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu L, Damen JE, Ware M, Hughes M, Krystal G. SHIP, a new player in cytokine-induced signalling. Leukemia. 1997;11:181–184. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huber M, Helgason CD, Damen JE, Scheid M, Duronio V, Liu L, Ware MD, Humphries RK, Krystal G. The role of SHIP in growth factor induced signalling. Progress in Biophysics & Molecular Biology. 1999;71:423–434. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(98)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Helgason CD, Antonchuk J, Bodner C, Humphries RK. Homeostasis and regeneration of the hematopoietic stem cell pool is altered in SHIP-deficient mice. Blood. 2003 doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Desponts C, Hazen AL, Paraiso KH, Kerr WG. SHIP deficiency enhances HSC proliferation and survival but compromises homing and repopulation. Blood. 2006;107:4338–4345. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hazen AL, Smith MJ, Desponts C, Winter O, Moser K, Kerr WG. SHIP is required for a functional hematopoietic stem cell niche. Blood. 2009;113:2924–2933. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu J, Garrett R, Jung Y, Zhang Y, Kim N, Wang J, Joe GJ, Hexner E, Choi Y, Taichman RS, Emerson SG. Osteoblasts support B-lymphocyte commitment and differentiation from hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2007;109:3706–3712. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Helgason CD, Kalberer CP, Damen JE, Chappel SM, Pineault N, Krystal G, Humphries RK. A dual role for Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol-5-phosphatase (SHIP) in immunity: aberrant development and enhanced function of b lymphocytes in ship -/- mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2000;191:781–794. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brauweiler A, Tamir I, Dal Porto J, Benschop RJ, Helgason CD, Humphries RK, Freed JH, Cambier JC. Differential regulation of B cell development, activation, and death by the src homology 2 domain-containing 5′ inositol phosphatase (SHIP) Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2000;191:1545–1554. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakamura K, Kouro T, Kincade PW, Malykhin A, Maeda K, Coggeshall KM. Src homology 2-containing 5-inositol phosphatase (SHIP)suppresses an early stage of lymphoid cell development through elevated interleukin-6 production by myeloid cells in bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2004;199:243–254. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maeda K, Mehta H, Drevets DA, Coggeshall KM. IL-6 increases B-cell IgG production in a feed-forward proinflammatory mechanism to skew hematopoiesis and elevate myeloid production. Blood. 115:4699–4706. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-230631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Desponts C, Ninos JM, Kerr WG. s-SHIP associates with receptor complexes essential for pluripotent stem cell growth and survival. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;15:641–646. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu Q, Oliveira-Dos-Santos AJ, Mariathasan S, Bouchard D, Jones J, Sarao R, Kozieradzki I, Ohashi PS, Penninger JM, Dumont DJ. The inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase ship is a crucial negative regulator of B cell antigen receptor signaling. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1998;188:1333–1342. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.7.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ono M, Okada H, Bolland S, Yanagi S, Kurosaki T, Ravetch JV. Deletion of SHIP or SHP-1 reveals two distinct pathways for inhibitory signaling. Cell. 1997;90:293–301. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marechal Y, Pesesse X, Jia Y, Pouillon V, Perez-Morga D, Daniel J, Izui S, Cullen PJ, Leo O, Luo HR, Erneux C, Schurmans S. Inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate controls proapoptotic Bim gene expression and survival in B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13978–13983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704312104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marechal Y, Queant S, Polizzi S, Pouillon V, Schurmans S. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase B controls survival and prevents anergy in B cells. Immunobiology. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wahle JA, Paraiso KH, Costello AL, Goll EL, Sentman CL, Kerr WG. Cutting edge: dominance by an MHC-independent inhibitory receptor compromises NK killing of complex targets. J Immunol. 2006;176:7165–7169. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kerr WG. Acquisition and remodeling of the NK receptor repertoire. In: Brossay L, editor. Everything You Wanted to Know About NK Cells, But Were Afraid to Ask. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ghansah T, Paraiso KH, Highfill S, Desponts C, May S, McIntosh JK, Wang JW, Ninos J, Brayer J, Cheng F, Sotomayor E, Kerr WG. Expansion of myeloid suppressor cells in SHIP-deficient mice represses allogeneic T cell responses. J Immunol. 2004;173:7324–7330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marti F, Xu CW, Selvakumar A, Brent R, Dupont B, King PD. LCK-phosphorylated human killer cell-inhibitory receptors recruit and activate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:11810–11815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu R, Abramson J, Fridkin M, Pecht I. SH2 domain-containing inositol polyphosphate 5′-phosphatase is the main mediator of the inhibitory action of the mast cell function-associated antigen. J Immunol. 2001;167:6394–6402. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abramson J, Xu R, Pecht I. An unusual inhibitory receptor--the mast cell function-associated antigen (MAFA) Mol Immunol. 2002;38:1307–1313. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fortenbery NR, Paraiso KH, Taniguchi M, Brooks C, Ibrahim L, Kerr WG. SHIP influences signals from CD48 and MHC class I ligands that regulate NK cell homeostasis, effector function, and repertoire formation. J Immunol. 184:5065–5074. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim S, Poursine-Laurent J, Truscott SM, Lybarger L, Song YJ, Yang L, French AR, Sunwoo JB, Lemieux S, Hansen TH, Yokoyama WM. Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature. 2005;436:709–713. doi: 10.1038/nature03847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Johansson S, Johansson M, Rosmaraki E, Vahlne G, Mehr R, Salmon-Divon M, Lemonnier F, Karre K, Hoglund P. Natural killer cell education in mice with single or multiple major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1145–1155. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Khoo NK, Fahlen L, Sentman CL. Modulation of Ly49A receptors on mature cells to changes in major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Immunology. 1998;95:126–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paraiso KH, Ghansah T, Costello A, Engelman RW, Kerr WG. Induced SHIP deficiency expands myeloid regulatory cells and abrogates graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2007;178:2893–2900. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Neill L, Tien AH, Rey-Ladino J, Helgason CD. SHIP-deficient mice provide insights into the regulation of dendritic cell development and function. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:627–639. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Antignano F, Ibaraki M, Kim C, Ruschmann J, Zhang A, Helgason CD, Krystal G. SHIP is required for dendritic cell maturation. J Immunol. 184:2805–2813. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shlomchik WD, Couzens MS, Tang CB, McNiff J, Robert ME, Liu J, Shlomchik MJ, Emerson SG. Prevention of graft versus host disease by inactivation of host antigen-presenting cells. Science. 1999;285:412–415. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Freeburn RW, Wright KL, Burgess SJ, Astoul E, Cantrell DA, Ward SG. Evidence that SHIP-1 contributes to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate metabolism in T lymphocytes and can regulate novel phosphoinositide 3-kinase effectors. J Immunol. 2002;169:5441–5450. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tomlinson MG, Heath VL, Turck CW, Watson SP, Weiss A. SHIP family inositol phosphatases interact with and negatively regulate the Tec tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55089–55096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408141200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tessmer MS, Fugere C, Stevenaert F, Naidenko OV, Chong HJ, Leclercq G, Brossay L. KLRG1 binds cadherins and preferentially associates with SHIP-1. Int Immunol. 2007;19:391–400. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dong S, Corre B, Foulon E, Dufour E, Veillette A, Acuto O, Michel F. T cell receptor for antigen induces linker for activation of T cell-dependent activation of a negative signaling complex involving Dok-2, SHIP-1, and Grb-2. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2509–2518. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Collazo MM, Wood D, Paraiso KH, Lund E, Engelman RW, Le CT, Stauch D, Kotsch K, Kerr WG. SHIP limits immunoregulatory capacity in the T-cell compartment. Blood. 2009;113:2934–2944. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-181164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Locke NR, Patterson SJ, Hamilton MJ, Sly LM, Krystal G, Levings MK. SHIP regulates the reciprocal development of T regulatory and Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:975–983. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tarasenko T, Kole HK, Chi AW, Mentink-Kane MM, Wynn TA, Bolland S. T cell-specific deletion of the inositol phosphatase SHIP reveals its role in regulating Th1/Th2 and cytotoxic responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11382–11387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704853104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Helgason CD, Damen JE, Rosten P, Grewal R, Sorensen P, Chappel SM, Borowski A, Jirik F, Krystal G, Humphries RK. Targeted disruption of SHIP leads to hemopoietic perturbations, lung pathology, and a shortened life span. Genes & Development. 1998;12:1610–1620. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Karlsson MC, Guinamard R, Bolland S, Sankala M, Steinman RM, Ravetch JV. Macrophages control the retention and trafficking of B lymphocytes in the splenic marginal zone. J Exp Med. 2003;198:333–340. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lo TC, Barnhill LM, Kim Y, Nakae EA, Yu AL, Diccianni MB. Inactivation of SHIP1 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia due to mutation and extensive alternative splicing. Leuk Res. 2009;33:1562–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kashiwada M, Cattoretti G, McKeag L, Rouse T, Showalter BM, Al-Alem U, Niki M, Pandolfi PP, Field EH, Rothman PB. Downstream of tyrosine kinases-1 and Src homology 2-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase are required for regulation of CD4+CD25+ T cell development. J Immunol. 2006;176:3958–3965. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Swedin JM, Lucas PJ, Gress RE, Levine BL, June CH, Serody JS, Blazar BR. L-Selectin(hi) but not the L-selectin(lo) CD4+25+ T-regulatory cells are potent inhibitors of GVHD and BM graft rejection. Blood. 2004;104:3804–3812. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kerr WG, Park MY, Maubert M, Engelman RW. SHIP deficiency causes Crohn's disease-like ileitis. Gut. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.202283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cox D, Dale BM, Kashiwada M, Helgason CD, Greenberg S. A regulatory role for Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase(SHIP) in phagocytosis mediated by Fc gamma receptors and complement receptor 3 (alpha(M)beta(2); CD11b/CD18) J Exp Med. 2001;193:61–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ganesan LP, Joshi T, Fang H, Kutala VK, Roda J, Trotta R, Lehman A, Kuppusamy P, Byrd JC, Carson WE, Caligiuri MA, Tridandapani S. FcgammaR-induced production of superoxide and inflammatory cytokines is differentially regulated by SHIP through its influence on PI3K and/or Ras/Erk pathways. Blood. 2006;108:718–725. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kamen LA, Levinsohn J, Cadwallader A, Tridandapani S, Swanson JA. SHIP-1 increases early oxidative burst and regulates phagosome maturation in macrophages. J Immunol. 2008;180:7497–7505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Takeshita S, Namba N, Zhao JJ, Jiang Y, Genant HK, Silva MJ, Brodt MD, Helgason CD, Kalesnikoff J, Rauh MJ, Humphries RK, Krystal G, Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. SHIP-deficient mice are severely osteoporotic due to increased numbers of hyper-resorptive osteoclasts. Nat Med. 2002;8:943–949. doi: 10.1038/nm752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bronte V, Wang M, Overwijk WW, Surman DR, Pericle F, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Apoptotic death of CD8+ T lymphocytes after immunization: induction of a suppressive population of Mac-1+/Gr-1+ cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:5313–5320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gabrilovich DI, Bronte V, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Ochoa A, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Schreiber H. The terminology issue for myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:425. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3037. author reply 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Thornton AM, Shevach EM. CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells suppress polyclonal T cell activation in vitro by inhibiting interleukin 2 production. J Exp Med. 1998;188:287–296. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]