Abstract

Introduction

Emerging adults (ages 18 to 25) are more likely to use e-cigarettes compared to other age groups, but little is known about their risk and protective factors. A next step to understanding e-cigarette use among emerging adults may involve examining how transition-to-adulthood themes are associated with e-cigarette use. It may also be important to know which specific transitions, and how the accumulated number of role transitions experienced in emerging adulthood, are associated with e-cigarette use.

Methods

Emerging adults completed surveys indicating their identification with transition-to-adulthood themes, role transitions in the past year, and e-cigarette use. Logistic regression models examined the associations between transition-to-adulthood themes and e-cigarette use. Separate logistic regression models explored the association between individual role transitions, as well as the accumulated number of role transitions experienced, and e-cigarette use, controlling for age, gender, and ethnicity.

Results

Among the participants (n=555), 21% were male, the average age was 22, 45% reported lifetime, and 12% reported past-month, e-cigarette use. Participants who felt emerging adulthood was a time of experimentation/possibility were more likely to report e-cigarette use. Several role transitions were found to be associated with e-cigarette use such as loss of a job, dating someone new, and experiencing a breakup. The relationship between the accumulated number of role transitions and e-cigarette use was curvilinear.

Conclusion

Findings from this pilot study can be a point of departure for future studies looking to understand the risk and protective factors of e-cigarettes among emerging adults.

Keywords: Electronic cigarettes, E-cigarettes, Emerging Adults, Vape, Young Adults, Prevention

1. Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) were introduced into the U.S. market in the mid 2000s (Cobb, & Abrams, 2014). Today, more than 250 e-cigarette brands are available in retail stores and online (Benowitz, 2013). Expenditures for e-cigarette advertising increased from $6.4 million in 2011 to $18.3 million in 2012 (Kim, Arnold, Makarenko, 2014) with health claims that are unsubstantiated by the present scientific evidence used to sell this product (Grana & Ling, 2014; The Lancet 2014). The number of e-cigarette users in the U.S. alone is estimated to be 2.5 million (Cressey, 2013), with annual e-cigarette sales in the U.S. expected to surpass $2.0 billion in 2014 (Cobb & Abrams, 2014).

Our understanding of what drives the use of e-cigarettes lags behind the growth in popularity of this tobacco product. The current literature does not provide a comprehensive understanding of the personal, social, and cultural risk and protective factors associated with e-cigarette use among the general population. Even less is known about e-cigarette use among individuals from ethnically diverse backgrounds, or among individuals in emerging adulthood (ages 18 to 25), the phase of the life course when experimentation with substances is highest (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012; SAMHSA, 2012).

Population-based surveys have found that emerging adults were more likely to use e-cigarettes compared to other age groups (McMillen, Maduka, & Winickoff, 2012; McMillen, Gottlieb, Shaefer, Winickoff, & Klein, 2014; Coleman et al., 2014). The factors that drive e-cigarette use among this population, however, remain unclear and warrant further investigation (Carroll, Chapman, & Wu, 2014). The research on e-cigarette use among emerging adults has been comprised of focus groups among college students, or survey research on regional samples with limited survey measures. One focus group study illustrated that emerging adults perceived e-cigarettes as accessible, convenient, and modern (Choi, Fabian, Mottey, Corbett, & Forster, 2012). Findings from a midwestern regional sample of emerging adults showed that 7.0% reported lifetime, and about 1% reported past-month use of e-cigarettes (Choi, & Forster, 2013). Most participants believed that e-cigarettes could help people quit smoking, are less harmful than combustible cigarettes, and about a quarter believed that e-cigarettes are less addictive than combustible cigarettes (Choi, & Forster, 2013). Positive expectations about the use of e-cigarettes have been associated with e-cigarette use in cross sectional (Pokhrel, Little, Fagan, Muranaka, & Herzong, 2014), and longitudinal research among emerging adults (Choi & Forster, 2014).

Studies on e-cigarette use among college students have been conducted on predominantly non-Hispanic White samples. Sutfin, McCoy, Morrell, Hoeppner, and Wolfson (2013) performed one of the largest studies on e-cigarette use among emerging adults, with a study sample comprised of 80% non-Hispanic White students residing in North Carolina. In order to identify additional factors associated with e-cigarette use among this population, it is important that research be conducted with diverse groups of emerging adults.

Emerging adulthood is characterized by change, identity exploration, and development (Arnett, 2011). A next step to understanding e-cigarette use among emerging adults may involve examining how transition-to-adulthood themes, or how the specific thoughts and feelings regarding emerging adulthood, are associated with e-cigarette use. Transition-to-adulthood themes have been found to be associated with substance use in earlier studies. For example, participants who felt emerging adulthood was a time of experimentation/possibility were more likely to report cigarette smoking and alcohol and marijuana use (Lisha et al., 2014), while in a separate study participants who felt emerging adulthood was a time to focus on others were less likely to report binge drinking and marijuana use (Allem, Lisha, Soto, Baezconde-Garbanati, & Unger, 2013). The present study examined which transition-to-adulthood themes are associated with e-cigarette use among a sample of emerging adults.

In emerging adulthood young people may experience multiple life transitions and have the time to explore and develop (Arnett, 2000). Role transitions (e.g., starting to date, a new job) may lead to substance use (Arnett, 2005), including experimentation with e-cigarettes. Role transitions have been previously found to be associated with cigarette use, (Allem, Soto, Baezconde-Garbanati, & Unger, 2013) as well as binge drinking and marijuana use among emerging adults (Allem et al., 2013a). The accumulated number of role transitions experienced in emerging adulthood has been associated with hard drug use among emerging adults (Allem, Soto, Baezconde-Garbanati, & Unger, 2015). The stress associated with navigating the changes in critical periods of the life course may lead emerging adults to engage in e-cigarette use, possibly as a coping mechanism (Khantzian, 1997; Sinha, 2008). The present study examined which specific role transitions are associated with e-cigarette use, as well as whether the accumulated number of role transitions experienced in emerging adulthood is associated with e-cigarette use among a sample of emerging adults.

2. Methods

In order to survey an ethnically and sociodemographically diverse sample of emerging adults, we coordinated with administrators from two colleges in the California State University (CSU) system in the Los Angeles area. These two schools were among the most ethnically diverse in the CSU system (College Portraits, 2013). Campus wide emails were circulated and administrators from each college campus posted flyers and announced the current study on their respective CSU portal systems (accessible by each campus homepage). Students received a description of the study, were guaranteed confidentiality, and electronically signed consent forms. This study employed a web-based survey tool that allowed participants to click on a link on a computer or smart phone and submit responses electronically. All respondents were offered a five-dollar gift card after they had completed the survey. All data were de-identified for analytic purposes, and the institutional review board of the principal investigator’s University approved all study procedures.

2.1 Measures

Transition-to-adulthood themes were assessed with the Inventory of the Dimensions of Emerging Adulthood (IDEA) (Reifman, Arnett, & Colwell, 2007). The IDEA instrument has six subscales, which measure the main themes or pillars of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000). The survey items were prompted with “Please think about this time in your life. By ‘time in your life,’ we are referring to the present time, plus the last few years that have gone by, and the next few years to come, as you see them. In short, you should think about a roughly five-year period, with the present time right in the middle. Is this time in your life a …” Responses for each item included “strongly disagree” coded 1, “somewhat disagree” coded 2, “agree” coded 3, and “strongly agree” coded 4. The subscales, corresponding reliability coefficient, and an example question are as follows: Identity Exploration (Cronbach's alpha [α]=0.83) e.g., “time of finding out who you are?”, Experimentation/Possibilities (α=0.78) e.g., “time of many possibilities?”, Negativity/Instability (α=0.82) e.g., “time of confusion?”, Other-Focused e.g., (α=0.66) “time of responsibility for others?”, Self-Focused (α=0.77) e.g., “time of personal freedom?”, and Feeling “In-Between” (α=0.72) e.g., “time of feeling adult in some ways but not others?”.

The list of role transitions was developed by Allem and colleagues (2013), and modified for the present study to include 22 non-redundant role transitions. The survey items for these 22 transitions were prompted with “Has this happened to you in the last year?” with responses coded 1 “yes” or 0 “no”. The 22 items were, “Started dating someone,” “Started a new romantic relationship,” “Got engaged,” “Got married,” “Moved in with boyfriend or girlfriend,” “Broke up with boyfriend or girlfriend,” “Got a divorce,” “Had a baby,” “Lost a baby,” “Got a new job,” “Lost a job,” “You were demoted or forced to work fewer hours,” “You were unemployed, seeking work but unable to find it,” “Had to care for a parent or relative,” “Stopped having to care for a parent or relative,” “Had to babysit siblings or family members,” “Stopped babysitting siblings or family members,” “Got extremely ill,” “Overcame serious illness,” “Were arrested,” “Became addicted to drugs or alcohol,” and “Overcame addiction to drugs or alcohol.” Summing the 22 individual role transitions created the measure of accumulated number of role transitions. The highest 1.5% of total transitions experienced (>9 transitions) was recoded as the 98.5% value (8 transitions). This adjustment prevented extrapolation to a very small group where very few cases were observed but reduced the skewness of the measure.

The two outcomes of interest were lifetime and past-month e-cigarette use. Survey items on e-cigarette use were prompted with the following statement, “The next few questions are about electronic or e-cigarettes, also called vape pens or e-hookahs. E-cigarettes are battery operated and produce vapor instead of smoke. There are also e-pipes and e-cigars. Some e-cigarettes are disposable and some are rechargeable. Fluid for e-cigarettes comes in many different flavors and nicotine concentrations and is sometimes called ‘juice’ or ‘e-juice’. When we ask bout an ‘e-cigarette’ in the next few questions, we mean any product that fits this description.” Each outcome was coded 1 “yes” and 0 “no” with a 1 indicating any use of an e-cigarette in the specified time period e.g., lifetime use, and past-month use. Age was coded in years, and gender was coded 1 “male” or 0 “female.” Race/ethnicity was coded into five categories: 1) non-Hispanic White, 2) Hispanic or Latino/a, 3) Black or African American, 4) Other (Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander), and 5) multiracial. When the measure of race/ethnicity was used in analyses, indicator variables represented each group with non-Hispanic Whites used as the reference category in regression models.

2.2 Analysis plan

Given the two colleges used as sampling sites, students attending the same college may have shared similar characteristics relative to those who did not. However, appropriate diagnostics revealed that intraclass correlation (ICC) was negligible in this study. For example, the ICCs were 4.08 × 10−16 and 2.37 × 10−22 for lifetime and past-month e-cigarette use respectively.

The present study examined which transition-to-adulthood themes are associated with e-cigarette use. Initially, lifetime and past-month e-cigarette use were each regressed on the six subscales of emerging adulthood. Lifetime and past-month e-cigarette use were then each regressed on the significant subscales while controlling for age, gender, and ethnicity. The events per variable (EPV) rule in logistic regression suggested separate models were appropriate. The EPV rule recommends 10 to 15 cases (“1s” in the dependent variable in this instance) for each explanatory variable in the model. This study had 68 past-month e-cigarette users, suggesting more than 6 explanatory variables in any one model would have run the high risk of overfitting the model (Greenland, 1989; Harrell, Lee & Mark, 1996).

The present study also examined if the accumulated number of role transitions experienced in emerging adulthood is associated with e-cigarette use. Bivariable associations between the accumulated number of role transitions and e-cigarette use were plotted using locally weighted scatter plot smoothing (lowess) as described by Cleveland (1997), and applied to tobacco-related behavior by Allem and colleagues (2012). Lowess is a desirable smoothing method because it tends to follow the data. A .80 bandwidth was used so that the associations grossly fit the general trends. Alternative bandwidths (e.g., .67 and .90) were used to verify the original patterns. This analysis demonstrated that the relationship between the accumulated number of role transitions and e-cigarette use was curvilinear. Spline logistic regressions with knots to approximate the association between role transitions and e-cigarette use were then computed controlling for age and gender. A knot at five transitions was determined appropriate. In other words, the relationship between e-cigarette use and the accumulated number of role transitions dramatically changed after five transitions, where those who experienced between zero and five transitions were more likely to report lifetime as well as past-month e-cigarette use, while those who reported more than five transitions were less likely to report lifetime and past-month e-cigarette use.

Lastly, the present study examined which specific role transitions are associated with e-cigarette use. To avoid potential problems of multicollinearity as well as overfitting the model, 22 generalized linear models examined the relationships between each transition and e-cigarette use controlling for age, gender, and ethnicity. Given the nature of the data (pilot study), relationships between specific role transitions and e-cigarette use significant at p<.05 were reported. Associations significant after a Bonferonni correction (p-values < .002 [.05/22]) were distinguished. For all analyses, the quantity of interest was calculated using the estimates from a multivariable analysis by simulation using 1,000 randomly drawn sets of estimates from a sampling distribution with mean equal to the maximum likelihood point estimates, and variance equal to the variance-covariance matrix of the estimates, with covariates held at their mean values (King, Tomz, & Wittenberg, 2000).

3. Results

Among the participants (n=555), 79% were female, the average age was 22, 45% reported lifetime, and 12% reported past-month, e-cigarette use. Males were significantly more likely to report lifetime e-cigarette use compared to females (57% vs. 42%; p=0.0061), but did not differ on past-month e-cigarette use. The sample was ethnically diverse, with 18% non-Hispanic White, 46% Hispanic or Latino/a, 12% African American or Black, 10% multiracial and 14% other. E-cigarette use did not differ across race/ethnicity in either the case of lifetime use (χ2(4)=7.6512; p=0.105) or past-month use (χ2(4)=0.7216; p=0.949).

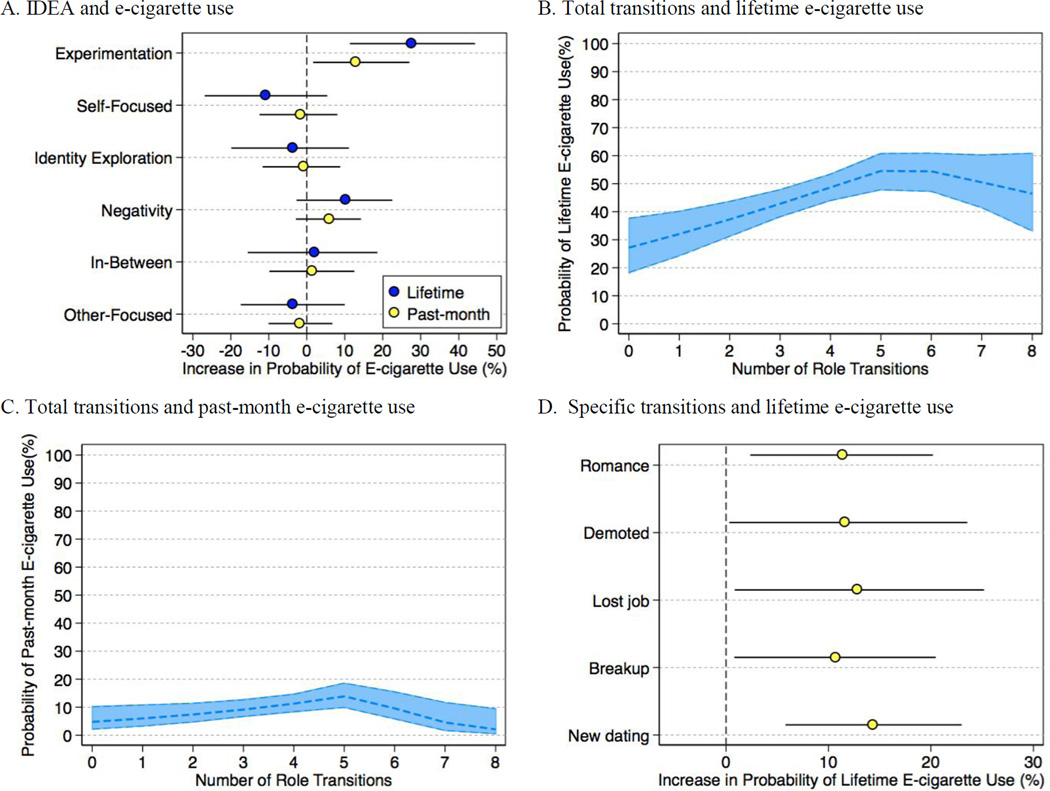

Participants who felt emerging adulthood was a time of experimentation/possibility were more likely to report e-cigarette use. A difference in score on the experimentation/possibility subscale between the 10th percentile and the 90th percentile was associated with a 28% (95% Confidence Interval [CI], 11% to 44%) higher probability of lifetime e-cigarette use, and a 13% (95% CI 2% to 27%) higher probability of past-month e-cigarette use (Figure 1A). Conclusions did not change after controlling for age, gender and ethnicity. The remaining IDEA subscales were not significantly associated with lifetime or past-month e-cigarette use.

Figure 1.

(A) Shows the difference in predicted probabilities of lifetime and past-month e-cigarette use when the 10th and 90th percentile IDEA scores are included in computations with 95% confidence intervals. (B) Shows the predicted probability of lifetime e-cigarette use by number of role transitions. (C) Shows the predicted probability of past-month e-cigarette use by number of role transitions. (D) Shows the difference in predicted probability of lifetime e-cigarette use, with 95% confidence intervals. Estimates were calculated by simulating the first difference in each role transition e.g., experiencing a breakup from 0 to 1. All estimates were arrived by use of 1000 random drawn sets of estimates from each respective coefficient covariance matrix with control variables held at their mean values.

Estimates suggested that the increasing and decreasing trends between number of role transitions and e-cigarette use were significant at and before five as well as after five, using spline logistic regression with a knot at five transitions. A difference in the number of role transitions, from 0 to 5, was associated with a 27% (95% CI, 12 to 40) higher probability of lifetime e-cigarette use (Figure 1B). A difference in the number of role transitions, from 6 to 8, was associated with a −4% (95% CI, −6 to −1) decrease in probability of lifetime e-cigarette use. A difference in the number of role transitions, from 0 to 5, was associated with a 9% (95% CI, 2 to 15) higher probability of past-month e-cigarette use (Figure 1C). A difference in the number of role transitions, from 6 to 8, was associated with a −3% (95% CI, −4 to −2) decrease in probability of past-month e-cigarette use.

Specific role transitions were associated with lifetime e-cigarette use (Figure 1D). Participants who started to date someone new, started a new romantic relationship, or experienced a breakup were 14% (95% CI, 6 to 23), 11% (95% CI, 2 to 20), and 11% (95% CI, 1 to 20) more likely to report lifetime e-cigarette use compared with those who did not, respectively. Participants who reported loss of a job or experienced a demotion were 13% (95% CI, 1 to 26) and 12% (95% CI, 0 to 23) more likely to report lifetime e-cigarette use compared with those who did not, respectively. The association between dating someone new and lifetime e-cigarette use was significant after the Bonferonni correction with p<.002. Specific role transitions were not significantly related to past-month e-cigarette use.

4. Conclusion

The present study identified one transition-to-adulthood theme that was associated with e-cigarette use. Feeling that emerging adulthood was a time of experimentation/possibility was associated with an increased probability of e-cigarette use. Themes of experimentation/possibility have previously been found to be associated with substance use (Lisha et al., 2014; Allem et al., 2013). Similarly, curiosity was determined to be one of the top reasons for e-cigarette experimentation among a sample of adolescents and emerging adults (Kong, Morean, Cavallo, Camenga, & Krishnan-Sarin, 2014). These themes should be discussed in prevention programs with an emphasis on promoting recreational activities that introduce emerging adults to new/exciting activities that fulfill their need for experimentation/possibilities that are distinct from using emerging tobacco products. Activities might include sports, art, entertainment activities, or business ventures. Oftentimes these activities are less available post-high school, but might be important to incorporate in these older age groups.

The present study also identified the group of emerging adults at highest risk of e-cigarette use based on their accumulated number of role transitions experienced. Findings suggested that those who experienced five transitions were at highest risk of e-cigarette use. Alternatively, those who experienced more than five were significantly less likely to use e-cigarettes. This curvilinear relationship is in contrast to prior research that found a linear relationship between the accumulated number of role transitions and hard drug use among emerging adults (Allem et al., 2015). The curvilinear patterns may reflect two distinct groups of emerging adults. Emerging adults managing many transitions may not have time to experiment with e-cigarettes, while emerging adults managing fewer transitions may have excess time lending to idleness and experimentation with e-cigarettes. Emerging adulthood is a time of increased freedom that often comes with more time to choose how to spend it. Prevention programs should communicate to emerging adults that filling idle time with nicotine experimentation should be avoided and alternative activities should be promoted instead. Conversely, certain emerging adults may be overwhelmed by multiple transitions and use e-cigarettes as a maladaptive coping strategy. Those who experience many transitions may already have sufficient coping skills in place that allow them to take on many transitions without looking to nicotine to alleviate stress. This interpretation, however, should be considered in the context of the other findings of this study. Due to the significant relationship between the theme of experimentation/possibility and e-cigarette use, and the insignificant relationship between the theme of negativity/instability and e-cigarette use, it may be the case that e-cigarettes are used to deal with boredom rather than stress. In other words, if e-cigarette use were associated with the theme of negativity/instability there would be more evidence that e-cigarettes are used as a coping mechanism in the face of many transitions.

Specific role transitions were associated with lifetime e-cigarette use but not past-month use. For example, starting and ending romantic relationships was associated with e-cigarette use as well as fluctuations (e.g., lost job, demotion) in participants’ work lives. While prior studies have found starting and ending romantic relationships were associated with past-month cigarette use (Allem et al., 2013a), and past-month hard drug use (Allem, et al., 2015), among emerging adults, the present study did not find an association between these transitions and past-month e-cigarette use. Setbacks in the process of securing full-time employment, or maintaining part-time employment, may drive emerging adults to drink or smoke cigarettes as a way to alleviate negative affect. Nicotine often found in e-cigarettes, however, may not be perceived by emerging adults as a way to alleviate negative affect. Future research should explore these associations in a population-based sample of emerging adults before a definitive conclusion is drawn.

4.1 Limitations

The relationship between role transitions and e-cigarette use was analyzed at a single time point. Future longitudinal studies should determine whether role transitions precede use of e-cigarettes or whether role transitions are associated with frequency of e-cigarette use (e.g., going from initiation to daily use). The role transitions in this study may not include all transitions that are experienced by emerging adults that could be associated with e-cigarette use. The IDEA instrument may not be a perfect measure of transition-to-adulthood themes, but currently is the only scale available to assess these constructs. E-cigarette use was a dichotomous outcome, limiting the understanding of frequency of use. This study’s sample under represents males, and findings may not generalize to emerging adults in other regions of the U.S. or to those not enrolled in college.

Notwithstanding these limitations, findings from the present study addresses research priorities of the FDA Center for Tobacco Products by describing behaviors of individuals using e-cigarettes and identifying cognitive and affective factors associated with e-cigarette use among emerging adults. By appreciating the unique characteristics in emerging adulthood, these findings make a contribution to the limited literature on e-cigarette use among emerging adults. E-cigarette use poses concerns to public health including emerging adults initiating in smoking, and use of other nicotine products, undermining decades of health campaigns on the harms of smoking (The Lancet Oncology, 2013). Emerging adults who initiate e-cigarette use may struggle with a lifetime of nicotine dependence transitioning back and forth from e-cigarettes to combustible cigarettes. This dual use may also hinder cessation among current smokers. Additionally, e-cigarettes threaten to renormalize smoking (Benowitz, 2013). With these public health concerns in mind, understanding the correlates of e-cigarette use among a priority population like emerging adults is of utmost importance. Findings from this pilot study can be a point of departure for future studies looking to understand the risk and protective factors of e-cigarettes among emerging adults.

Highlights.

45% of participants reported lifetime and 12% reported past-month e-cigarette use.

Themes of experimentation were associated with e-cigarette use.

Those with fewer transitions were more likely to use e-cigarettes.

Transitions in romance were positively associated with e-cigarette use.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source:

Research reported in this publication was supported by Grant # P50CA180905 from the National Cancer Institute and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP), and Grant # T32CA009492 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or FDA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors:

Jon-Patrick Allem designed the concept of the study, was responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the first version of the manuscript. Jennifer B. Unger, Myriam Forster, and Adam Neiberger provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allem JP, Ayers JW, Unger JB, Irvin VL, Hofstetter CR, Hovell MF. Smoking trajectories among Koreans in Seoul and California: Exemplifying a common error in age parameterization. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2012;13(5):1851–1856. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.5.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem JP, Lisha NE, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. Emerging adulthood themes, role transitions and substance use among Hispanics in Southern California. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(12):2797–2800. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem JP, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. Role transitions in emerging adulthood are associated with smoking among Hispanics in Southern California. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013a;15(11):1948–1951. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem JP, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. The relationship between the accumulated number of role transitions and hard drug use among Hispanic emerging adults. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2015;47(1):60–4. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.1001099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood(s): The cultural psychology of a new life stage. In: Jensen LA, editor. Bridging cultural and developmental approaches to psychology: New synthesis in theory, research, and policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL. The regulatory challenge of electronic cigarettes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310(7):685–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.109501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll Chapman SL, Wu LT. E-cigarette prevalence and correlates of use among adolescents versus adults: a review and comparison. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014;54:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Fabian L, Mottey N, Corbett A, Forster J. Young adults’ favorable perceptions of snus, dissolvable tobacco products, and electronic cigarettes: findings from a focus group study. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(11):2088–2093. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Forster J. Characteristics associated with awareness, perceptions and use of electronic nicotine delivery systems among young US Midwestern adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(3):556–561. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Forster J. Beliefs and experimentation with electronic cigarettes: a prospective analysis among young adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46(2):175–178. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1979;74(368):829–836. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb NK, Abrams DB. The FDA, e-Cigarettes, and the demise of combusted tobacco. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(16):1469–1471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1408448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman BN, Apelberg BJ, Ambrose BK, Green KM, Choiniere CJ, Bunnell R, King BA. Association between electronic cigarette use and openness to cigarette smoking among U.S. adults. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;2014:1–7. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- College Portraits. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.collegeportraits.org.

- Cressey D. Regulation stacks up for e-cigarettes. Nature. 2013;501(7468):473. doi: 10.1038/501473a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grana RA, Ling PM. “Smoking revolution”: A content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46(4):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1989;79(3):340–349. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariate prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Statistics in Medicine. 1996;15(4):361–87. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AE, Arnold YA, Makarenko O. E-cigarette advertising expenditures in the U.S., 2011–12. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46(4):409–412. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G, Tomz M, Wittenberg J. Making the most of statistical analyses: improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science. 2000;44(2):341–355. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2669316. [Google Scholar]

- Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Experimentation and Discontinuation Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu257. ntu257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet. E-cigarettes: closing regulatory gaps. The Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1438–1438. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60701-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet Oncology. Time for e-cigarette regulation. The Lancet Oncology. 2013;14(11):1027–1027. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70468-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisha NE, Grana R, Sun P, Rohrbach L, Spruijt-Metz D, Reifman A, Sussman S. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Revised Inventory of the Dimensions of Emerging Adulthood (IDEA-R) in a sample of continuation high school students. Evaluation & the health professions. 2014;37(2):156–177. doi: 10.1177/0163278712452664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen RC, Gottlieb MA, Shaefer RMW, Winickoff JP, Klein JD. Trends in electronic cigarette use among U.S. adults: Use is increasing in both smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;2014:1–8. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen R, Maduka J, Winickoff J. Use of emerging tobacco products in the United States. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2012;2012(989474):1–8. doi: 10.1155/2012/989474. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/989474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Little MA, Fagan P, Muranaka N, Herzong TA. Electronic cigarette use outcome expectancies among college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(6):1062–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Arnett JJ, Colwell MJ. Emerging adulthood: Theory, assessment, and application. Journal of Youth Development. 2007;2(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1141(1):105–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the 2011 national sur- vey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings, NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4713. Rockville, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sutfin EL, McCoy TP, Morrell HE, Hoeppner BB, Wolfson M. Electronic cigarette use by college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;131(3):214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]