Abstract

Background

Heavy drinking is highly comorbid with nicotine and marijuana use among young adults. Yet, our knowledge about the longitudinal effects of nicotine and marijuana use (including onset timing and quantity/frequency) on heavy drinking and whether the effects vary by gender is very limited. This study aims to characterize gender-specific developmental trajectories of multiple substance use and examine gender differences in the effects of nicotine and marijuana use on heavy drinking.

Methods

We conducted secondary analysis on 8 waves of data from 850 high risk youth who were recruited as ninth graders with low GPA in an economically disadvantaged school district in the Midwest, and were followed up annually to young adulthood. Onset ages and quantity/frequency of multiple substance use were assessed by a self-report questionnaire at each wave. The time-varying effect model and linear mixed model were adopted for statistical analysis.

Results

Males’ levels of heavy drinking, nicotine use, and marijuana use tended to grow persistently from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Females, on the other hand, only gradually increased their nicotine use across time while maintaining low levels of heavy drinking and marijuana use. Controlling for the early onset status of alcohol use, early onset statuses of nicotine use and marijuana use both added additional risk for heavy drinking; late onset marijuana users were also at higher risk for heavy drinking than nonusers of marijuana. Controlling for substance use onset statuses, higher quantity/frequency of nicotine and marijuana use both contributed to more involvement in heavy drinking. We also found that the effect of nicotine use quantity on heavy drinking was greater among males.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates the longitudinal effects of onset timing and quantity/frequency of nicotine and marijuana use on heavy drinking. Our analysis of gender differences also identifies female youth’s nicotine use and male youth’s co-use of nicotine and alcohol as two important areas for future prevention and intervention work.

Keywords: Gender difference, heavy drinking, nicotine use, marijuana use, early onset

1. Introduction

Researchers have reported that heavy drinking is associated with many negative outcomes including alcohol use disorders, drug use disorders, poor health, violence/crime, and social/economic disadvantage (Berg et al., 2013; Bonomo et al., 2004; Dawson et al., 2008; Hill et al., 2000; Jennison, 2004; Tucker et al., 2005). Furthermore, researchers have demonstrated some gender differences in drinking patterns and risk factors for alcohol use (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). By understanding gender differences in developmental trajectories and risk factors of heavy drinking, particularly among high risk youth, we may be able to tailor prevention and early intervention efforts to the special timing and risk factors of each gender group and, thus, thwart progression to worse outcomes.

National data from the United States indicate that heavy drinking is highly comorbid with nicotine and marijuana use among young adults (Jackson et al., 2008). Chen and Jacobson (2012) analyzed four waves of data from a nationally representative sample of adolescents and found similar developmental trajectories for heavy drinking, nicotine use and marijuana use by gender: females tend to be involved in higher levels of substance use in early adolescence, whereas males exhibit greater increases across time and higher levels of use in mid-adolescence and early adulthood. A significant limitation of the study is that the developmental trajectories for all the three substances were derived by fitting quadratic growth models that pre-specified a simple shape for developmental changes, which may contribute to the similarity in trajectories across substances. Furthermore, the majority of existing longitudinal studies on substance abuse include predominantly White samples or college samples. To the best of our knowledge, no researchers have characterized gender-specific trajectories of heavy drinking, nicotine use, and marijuana use among minority samples who are at risk for dropout and related deleterious outcomes such as substance abuse. However, this kind of analysis may have important implications for prevention and intervention and thus is needed in the field.

Researchers report that early onset of drinking is highly predictive of subsequent heavy drinking (Eliasen et al., 2009; Jefferis et al., 2005; Muthén & Muthén, 2000; Pitkänen et al., 2005; Rossow & Kuntsche, 2013). D’Amico et al. (2001) investigated the association between early onset of nicotine use or marijuana use and heavy drinking among high school students over an academic year. A major limitation of their study, however, is that the association between early onset of nicotine or marijuana use and heavy drinking was established without taking into account the effect of early onset of alcohol use. It is, therefore, unclear if the observed association is simply a manifestation of the greater likelihood of being early onset drinkers among early onset users of nicotine or marijuana. Furthermore, a potential gender difference in such an association could have important implications for gender-specific intervention but has not yet been examined. Thus, it is a research question open to investigation. Moreover, the majority of existing studies reviewed above were based on predominantly White samples so the results may not be generalizable to the high risk minority population.

National data consistently indicate that smokers are at much greater risk for being involved in heavy drinking than nonsmokers (Harrison et al., 2008; Harrison & McKee, 2011; Jackson et al., 2002). Although marijuana use has been legalized in a growing number of states and its prevalence rate has increased drastically in recent years (Miech & Koester, 2012), studies of its effect on heavy drinking are sparse. Researchers have reported that both nicotine and marijuana use are associated with heavy drinking (Fenzel, 2005; Jessor et al., 2006), but neither research team found any significant gender differences in such association. The information derived from these studies is, however, limited because they studied predominantly White college students within a very narrow developmental period (the former was a cross-sectional study; the latter had 3 waves within 2 academic years). Jackson et al. (2008) analyzed 4 waves of data spanning ages 18 to 26 from a nationally representative sample of high school seniors and found that heavy drinking, nicotine use, and marijuana use are highly associated during emerging adulthood. Yet, whether the association is moderated by gender was not examined in that study. Furthermore, it is necessary to extend this line of research to the high risk youth in order to more fully understand the concomitant effects of other substances on heavy drinking.

This study fills in the current knowledge gaps by conducting secondary analysis of eight waves of data from a longitudinal study on predominantly Black youth at high risk for multiple substance use from adolescence to emerging adulthood (ages 14–24). The first objective of this study is to characterize the gender-specific developmental trajectories of heavy drinking, nicotine use, and marijuana use during this critical developmental period. In order to take full advantage of the relatively large number of waves in the data, we used the time-varying effect model (TVEM; Tan et al., 2012) that does not impose any particular shape on the trajectories, so we might gain better insights into the differences across gender groups and multiple substances. The second objective is to investigate the longitudinal effects of early onset status and quantity/frequency of nicotine and marijuana use on heavy drinking, controlling for early onset status of alcohol use. Unlike the majority of researchers who relied on retrospective reports of substance use onset, the onset ages of use for the three substances in this study were derived from youth reports across waves with the most prospective report as the best estimate, in order to minimize recall bias. The third objective is to examine gender differences in the developmental trajectories of heavy drinking, as well as in the effects of nicotine and marijuana use (including onset and quantity/frequency) on heavy drinking.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and sample

The Flint Adolescent Study (FAS) is an ongoing longitudinal study that aims to investigate both risk and protective factors for substance use and related health risk behaviors from adolescence to adulthood (Elkington et al., 2010; Stoddard & Zimmerman, 2011). The study recruited ninth-grade students with a GPA of 3.0 and below from the four public high schools in an economically disadvantaged school district in the Midwest. The grade cutoff was used to select the youth who were at high risk for many deleterious outcomes. Of the 979 adolescents who met criteria, 52 had left the public schools; 67 were consistently absent from school after several attempts to interview them; and 10 participants either refused to participate or were refused participation by their parents. Therefore, the final sample (N=850) represents 87% of the eligible youth who completed the data collection at Wave 1.

The participants were followed for eight waves. Waves 1–4 correspond to the participants’ high school years (1994–1997); Waves 5–8 correspond to the second through fifth years post high school (1999–2002). A response rate of 90% was maintained from Wave 1 to 4; a 68% response rate was maintained from Wave 5 to 8. Trained interviewers from a non-profit organization specializing in survey methodology conducted a structured 50–60 minute face-to-face interview with each participant, in school or a location that the participant identified as convenient and that provided adequate privacy with no interruptions. In addition, a questionnaire on substance use related behaviors was self-administered at the end of the interview to avoid under-report.

In this study, we analyzed 8 waves of data from 850 participants (50% males). The racial composition of this sample was: 80% Black, 17% White, and 3% mixture of Black and White. The high percentage Blacks (self-identified) makes this sample unique because the few large scale longitudinal studies on the risk and protective factors of substance abuse include predominantly White samples. We know relatively little about these issues among Black youth. On average, the highest education level of their parents was completing vocational/training school. About 94% of the participants had completed at least 4 waves of assessment. The two statistical models described under Analytic Approach were particularly designed to handle unequal numbers of repeated measures across participants. During this critical developmental period (ages 14 to 24), 92% of the participants had used alcohol, 82% had used nicotine, and 79% had used marijuana. Thus, this is a high risk sample in comparison to the general young adult population which has lower lifetime prevalence rates: 86% for alcohol use, 62% for nicotine use, and 51% for marijuana use (SAMHSA, 2011).

2.2. Measures

Onset ages of alcohol, nicotine, and marijuana use

Many of the questions in our questionnaire on substance use related behaviors were adopted from the Monitoring the Future national survey (Bachman et al., 1997). From Wave 1 to Wave 3, we asked about the onset ages of alcohol and marijuana use by the following questions: “How old were you when you first had any beer, wine, or liquor?”; “How old were you when you first used marijuana (grass, pot, weed)?” When there was discrepancy across waves, we took the age reported at the earliest wave as the best estimate since it was the least retrospective account (Parra et al., 2003). For individuals who did not use alcohol or marijuana until Wave 4 or later, we used the following questions to determine drinking onset: “How many times have you had alcoholic beverages to drink in the last 12 months?”; “How many times (if any) have you used marijuana (grass, pot, weed) or hashish during the last 12 months?” When the participant reported one time or greater for the first time, we took the participant’s age at that wave as the age of onset. In terms of nicotine use, participants were asked “ How old were you the first time you smoked a cigarette?” at each wave of the study. For any discrepancies across waves, we used the age reported at the earliest wave. In our study sample, the median onset age was 13 for alcohol use, 13 for nicotine use, and 14 for marijuana use. Thus, we defined the age for early onset use of each of the substances as the corresponding median age or younger.

Quantity/frequency of nicotine and marijuana use as well as heavy drinking

At each wave, we consistently asked about cigarette smoking in the past 30 days with a 0–6 scale (0=not at all; 1=less than one cigarette per day; 2=one to five cigarettes per day; 3=about one-half pack per day; 4=about one pack per day; 5=about one and one-half packs per day; and 6=two packs or more per day). We also asked about marijuana or hashish use in the last 30 days with a 0–6 scale (0=0 times; 1=1–2 times; 2=3–5 times; 3=6–9 times; 4=10–19 times; 5=20–39 times; 6=40+ times). Moreover, our questionnaire had two items related to heavy drinking. The first question was “Think back over the LAST TWO WEEKS. How many times have you had five or more drinks in a row? (A “drink” is a glass of wine, a bottle of beer, a shot glass of liquor, or a mixed drink.)” with a 0–5 scale (0=none; 1=once; 2=twice; 3=three to five times; 4=six to nine times; 5=ten or more times). The second question was “When you drink alcoholic beverages, how often do you drink enough to feel pretty high?” with a 0–4 scale (0=never; 1=a few times; 2=about half of the times; 3=nearly all of the times; 4=on nearly all of the occasions). These two items were highly correlated (r = 0.57). We standardized each of them (with the mean 0 and standard deviation 1) and used the mean score of these two items to be the measure of heavy drinking. Similar items have been adopted to construct measures of heavy drinking in national survey data (Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Jackson et al., 2002).

2.3. Analytic approach

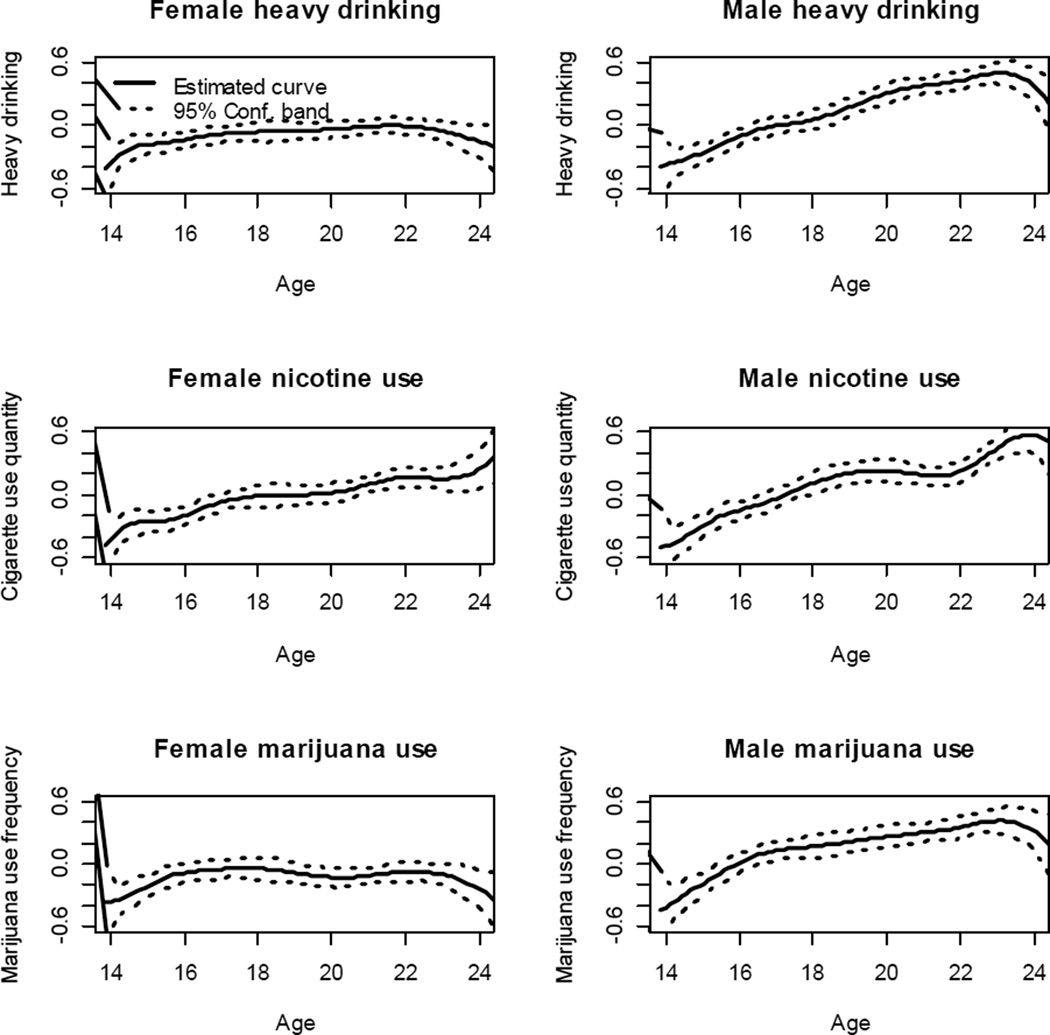

The first objective of this study is to characterize the gender-specific developmental trajectories of heavy drinking, nicotine use, and marijuana use from adolescence to emerging adulthood. We adopted the time-varying effect model (TVEM; Tan et al., 2012) because it does not impose strong parametric assumptions about the nature of developmental changes like traditional methods, which usually involve linear or quadratic shapes. Particularly, when the number of waves is relatively large like the case of the FAS, this new approach can take full advantage of the information contained in the rich longitudinal data. The TVEM SAS macro suite (Yang et al., 2012) was used to fit a flexible B-spline basis function for each gender group on each of the three substance use behaviors along the developmental age. These graphs allow us to visually compare the developmental patterns between gender groups, as well as across substances.

The second objective is to investigate the longitudinal effects of early onset status and quantity/frequency of nicotine and marijuana use on heavy drinking, controlling for early onset status of alcohol use. The linear mixed model (Verbeke and Molenberghs, 2000) was fit to examine such effects. The model took account of the non-independence of repeated measures within participants by involving random effects. We first modeled the trajectories of heavy drinking by entering the intercept, the linear term of age, and the quadratic term of age in order. The higher order terms were only kept in the models if they were significant (p<.01) given the lower order terms. Next, the early onset status of alcohol use was included as the control variable and remained in the model no matter whether it was significant or not, because we wanted to examine the effects of nicotine and marijuana use above and beyond the effect of early onset of alcohol use. Controlling for the trajectories and the effect of early onset of alcohol use, we tested the effects of early onset status of nicotine/marijuana use before the effect of quantity/frequency. We only kept the variables related to nicotine or marijuana use that had significant effects in the model. In the model building process, we constructed two dummy variables (the first variable contrasting early onset users versus the others; the second variable contrasting late onset users versus the others) and found that for alcohol and nicotine use, only the first variable was significant. Thus, for these two substances, we only included the first dummy variable in the analysis (i.e. non-users and late onset users together served as the reference group). In terms of marijuana use, both dummy variables were significant (i.e. non-users and late onset users were at different levels of risk) so we kept them in the model.

The third objective is to examine if there are gender differences in the developmental trajectories of heavy drinking, as well as in the effects of nicotine and marijuana use (including onset and quantity/frequency) on heavy drinking. To achieve this objective, we tested gender effects in the final stage of model building by entering the interactions between gender (male was coded as 1; female as 0) and each of the main effects remaining in the models from previous steps. Interactions were tested individually and only the significant interaction terms were retained in the final model.

3. Results

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics of demographic background, as well as lifetime prevalence, onset ages, and quantity/frequency of substance use by gender. At baseline, both gender groups were on average around 15 years old, with males a little bit older than females. On average, the highest parental education for the male group was at a slightly higher level (male: some college; female: vocational/training school). The two gender groups had about equivalent percentages of Blacks (overall 80%), lifetime alcohol users (overall 92%), lifetime nicotine users (overall 82%), and lifetime marijuana users (overall 79%). Males on average started drinking alcohol earlier than females (age 12.80 vs. 13.38). On the other hand, there was no gender differences in the onset ages of nicotine use (overall mean age at about 13) or marijuana use (overall mean age at about 14). Table 1 also shows gender-specific quantity/frequency of substance use during high school years (Wave 1–4) and post high school years (Wave 5–8). Because the original scales of substance use quantity/frequency were different, they were standardized across waves to facilitate interpretation of the magnitude and comparison across substances. For each participant, the mean of the standardized values across all the four waves during the high school years (or the post high school years) was used to summarize the individual’s substance use in that developmental period. Among females, the levels of heavy drinking and marijuana use in high school years were significantly higher than the corresponding levels in post high school years (p<.01). Males, on the other hand, were involved in higher levels of heavy drinking in post high school years (p<.01). In terms of gender differences, males only had a higher level of marijuana use than females in high school years, whereas males had significantly higher levels of involvement in all three substances during post high school years. Although this kind of macro-level analysis is useful, it does not provide a clear picture of the continuous developmental changes across this entire critical period (ages 14–24) for each gender group. Thus, we conducted another more sophisticated analysis described in the following paragraph.

Table 1.

Gender differences in demographic background and substance use including lifetime prevalence, onset ages, and quantity/frequency during high school and post high school years (N=850).

| Variable | Female M (SD) or % |

Male M (SD) or % |

|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline | 14.79 (0.62)* | 14.93 (0.66)* |

| Highest parental education level a | 4.16 (1.44)* | 4.54 (1.39)* |

| Percentage of Blacks | 81.41% | 78.82% |

| Percentage of lifetime alcohol users | 93.87% | 90.82% |

| Percentage of lifetime nicotine users | 83.76% | 79.53% |

| Percentage of lifetime marijuana users | 79.29% | 79.01% |

| Onset age of alcohol use | 13.38 (2.89)* | 12.80 (3.45)* |

| Onset age of nicotine use | 13.17 (2.52) | 13.24 (2.64) |

| Onset age of marijuana use | 14.11 (2.48) | 13.93 (2.44) |

| High school years: Wave 1–4 | ||

| Heavy drinking b | −0.03 (0.66) | 0.02 (0.68) |

| Cigarette use quantity b | −0.03 (0.80) | 0.06 (0.86) |

| Marijuana use frequency b | −0.07 (0.73)* | 0.09 (0.88)* |

| Post high school years: Wave 5–8 | ||

| Heavy drinking b | −0.17 (0.61)* | 0.21 (0.90)* |

| Cigarette use quantity b | −0.07 (0.88)* | 0.11 (0.94)* |

| Marijuana use frequency b | −0.21 (0.72)* | 0.18 (1.00)* |

Significant gender difference (p<.01) based on the two-sample t test (mean) or chi-square test (percentage).

1=completed grade school or less; 2=some high school; 3=completed high school; 4=vocational/training school; 5=some college; 6=completed college; 7=graduate/professional school after college.

Because the original scales of substance use quantity/frequency were different, they were standardized across waves to facilitate interpretation and comparison. The mean of repeated measures across waves was used to summarize an individual’s substance use level during a period.

To achieve the first objective of this study, we characterized the gender-specific developmental trajectories of heavy drinking, nicotine use, and marijuana use from ages 14 to 24, using the time-varying effect models. The estimated curves with 95% confidence bands are presented in Figure 1. Because the three substance use variables were originally in different measurement scales and thus were not comparable, we transformed all of them to standardized scores (with the mean 0 and standard deviation 1) to facilitate comparison across substances. In the beginning (at age 14), females and males were both involved in heavy drinking, nicotine use, and marijuana use at the same low level. Males tended to persistently increase their levels of involvement in all the three substances throughout this critical developmental period, whereas females only had a salient increasing trend in nicotine use across time. Conversely, females’ levels of heavy drinking and marijuana use stayed low throughout the entire period although a slight increase by age 16 and a small decrease after age 22 was found.

Figure 1.

Gender-specific developmental trajectories of heavy drinking, nicotine use, and marijuana use in standardized scales.

The linear mixed model was fit to achieve the second and third objectives of this study. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) based on an unconditional means model (Singer & Willett, 2003) was estimated to be 0.36, indicating that 36% of the total variance in heavy drinking may be attributable to differences among participants. Table 2 shows the fitted linear mixed model with the estimated fixed effects on the top and the variance components on the bottom. The trajectories of heavy drinking during this developmental period can be best delineated using the intercept, the linear term of age, as well as the quadratic term of age. This is consistent with the nonlinear nature of the curves observed in Figure 1. Early onset users of alcohol were at higher risk for heavy drinking in comparison to late onset users and nondrinkers. Controlling for the early onset status of alcohol use, early onset users of nicotine were at higher risk for heavy drinking in comparison to late onset users and nonsmokers. Given the onset statuses of alcohol and nicotine use, both the early onset and late onset statuses of marijuana use added additional risk for heavy drinking (relative to those who did not use marijuana). The effects of marijuana use onset statuses were greater than the effects of early onset statuses of the other two substances (the effect of early onset status of nicotine use was the smallest). We also compared these results with those based on a naïve model without controlling for alcohol use onset: the results were similar except that the estimated regression coefficients for the early onset of nicotine and marijuana use were higher (0.13 and 0.29, respectively), when the early onset of alcohol use was not controlled. Furthermore, controlling for the trajectories and substance use onset statuses, higher quantity/frequency of nicotine and marijuana use both contributed to more involvement in heavy drinking, with the effect of marijuana use greater than the effect of nicotine use.

Table 2.

The linear mixed model of longitudinal effects of nicotine and marijuana use on heavy drinking, controlling for the status of alcohol use onset (N=850).

| Parameter | Standard error | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trajectory | |||

| Intercept | −0.4720 | 0.0490 | .0001 |

| Age b | 0.0457 | 0.0132 | .0005 |

| Age2 b | −0.0033 | 0.0013 | .0104 |

| Substance use onset | |||

| Early onset of alcohol use | 0.1652 | 0.0349 | .0001 |

| Early onset of nicotine use | 0.0898 | 0.0343 | .0089 |

| Early onset of marijuana use | 0.2263 | 0.0445 | .0001 |

| Late onset of marijuana use | 0.1838 | 0.0461 | .0001 |

| Substance use quantity/frequency | |||

| Quantity of nicotine use a | 0.1171 | 0.0171 | .0001 |

| Frequency of marijuana use a | 0.2667 | 0.0119 | .0001 |

| Gender differences | |||

| Male | −0.0717 | 0.0421 | .0883 |

| Male × age b | 0.0422 | 0.0066 | .0001 |

| Male × nicotine use quantity a | 0.0978 | 0.0233 | .0001 |

| Variance components | |||

| Within-person | 0.4055 | ||

| Random intercept | 0.1242 |

The quantity of nicotine use and the frequency of marijuana use were standardized according to their means and standard deviations so the effects are comparable across substances.

Age was centered around 14 to facilitate the interpretation of the gender main effect.

In terms of the gender differences (the third objective), we did not find any significant interactions between gender and the substance use onset statuses so the final model (see Table 2) did not include these terms. Yet, we found significant interactions between gender and age as well as nicotine use quantity. To facilitate the interpretation of the gender main effect, age was centered around 14 (baseline) and nicotine use quantity was centered around the mean. Thus, when the quantity of nicotine use was held constant at the average level, males tended to have an insignificantly lower level of involvement in heavy drinking in the beginning of this critical developmental period, but the level increased at a significantly higher rate afterwards. Furthermore, the effect of quantity of nicotine use on heavy drinking was greater among males, whereas there was no gender difference in the effect of frequency of marijuana use.

4. Discussion

We found that males’ levels of heavy drinking, nicotine use, and marijuana use tended to grow persistently from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Females, on the other hand, only gradually increased their nicotine use across time while maintaining low levels of heavy drinking and marijuana use. Controlling for the early onset status of alcohol use, early onset statuses of nicotine use and marijuana use both added additional risk for heavy drinking; late onset marijuana users were also at higher risk for heavy drinking than nonusers of marijuana. Furthermore, controlling for substance use onset statuses, higher quantity/frequency of nicotine and marijuana use both contributed to more involvement in heavy drinking. We also found that the effect of nicotine use quantity on heavy drinking was greater among males whereas we found no gender difference in the effect of marijuana use frequency.

The effects of early onset and quantity/frequency of nicotine and marijuana use on heavy drinking that were found in this study may be explained by the Problem-Behavior Theory (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). According to the theory, heavy drinking is not an isolated behavior but covaries with other problem behaviors such as nicotine and marijuana use. Using one substance may lead to using others and using a little amount may lead to using a lot. Furthermore, early onset use of any substance may be an indicator of risk for a cluster of problem behaviors. The interrelatedness of problem behaviors may result from dynamic interactions between the individual’s personality (e.g. delinquency) and the environment (e.g. peer influence). Our finding of the longitudinal effect of marijuana use on heavy drinking is not well explained by the gateway theory (Kandel, 1995) that emphasizes the progression from licit drug use (alcohol or nicotine use) to marijuana use. Instead, it tends to provide more support for the common liability model (Degenhardt et al., 2010; Morral et al., 2002; Tarter et al., 2006) that hypothesizes a common factor for drug use propensity.

Our finding indicating that males had lower levels of heavy drinking in early adolescence, but increased more rapidly to higher levels in later development (based on the linear mixed model) was consistent with the result of longitudinal national survey data analyzed using a similar model (Chen & Jacobson, 2012). Females’ relatively higher risk for substance use in early adolescence may be explained by their earlier timing of physical puberty (Wichstrom, 2001). Other biological factors may, however, reduce females’ risk for substance use in later developmental stages such as higher reactivity to substance and greater vulnerability to adverse health effects due to substance use (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). The observed gender difference may also be explained by social-environmental factors such as greater social sanction against females’ substance use (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). The finding of a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population (Keyes et al., 2008) tends to reflect the diminishing gender-based drinking norms in the modern society.

While the developmental trajectories of females’ involvement in heavy drinking and marijuana use remained at lower levels, females’ levels of nicotine use increased developmentally, similar to the trajectories of males’ nicotine use. In fact, other longitudinal studies of adolescents have found more rapid increases in nicotine use across ages among females (Gabrhelik et al., 2012; Gutman et al., 2011). Other researchers also showed that girls developed signs of nicotine dependence at a faster rate (DiFranza et al., 2002; Thorner et al., 2007). Furthermore, Richardson et al. (2011) found that girls scored higher than boys on measures of emotional dependence and social attitudes associated with tobacco smoking. This finding may shed some light on designing future prevention and early intervention programs that particularly target female youth.

Although the association between early onset of alcohol use and later involvement in heavy drinking has been well-established, to the best of our knowledge, no study has ever investigated the potential risk of early onset of nicotine and marijuana use, controlling for the effect of early onset of alcohol use. Our finding that early onset statuses of nicotine use and marijuana use both added additional risk for heavy drinking, thus, fills in this important gap in the literature. Previous studies have found that adolescence is a critical period of brain and neurocognitive development that is essential for establishing life-long adult characteristics; and most importantly, such development is very likely to be disrupted by heavy alcohol use during adolescence (Crews & Hodge, 2007; Lisdahl et al., 2013). Thus, preventing heavy drinking among adolescents could result in long-term health benefits. Our result implies that instead of trying to interrupt drinking trajectories later on, interventions should focus on delaying not only the onset of alcohol use but also the onset of nicotine and marijuana use.

We found that early onset users of alcohol and nicotine were at higher risk for heavy drinking than late onset users and nonusers; however, for marijuana use, both early onset users and late onset users were at higher risk than nonusers. This finding is consistent with the result of another longitudinal study (Flory et al., 2004), which indicated that early onset alcohol users were more dysfunctional in terms of psychosocial predictors and psychopathology outcomes than late onset users and nonusers, whereas for marijuana, the early onset and late onset users were both more dysfunctional than the nonusers. Flory et al. (2004) argued that these differences may relate to the fact that alcohol is a lot more available, particularly at social gatherings, but marijuana is harder to obtain, illegal in most states, and often used surreptitiously. This hypothesis may be further examined in those states where marijuana is widely accessible such as Colorado.

Our longitudinal model indicates that the effect of quantity of nicotine use on heavy drinking was greater among males. In fact, the national data (Falk et al., 2006) show that men were much more likely than women to use both alcohol and nicotine (27.5% vs. 16.4%, respectively). Furthermore, previous publications of the FAS data found that male adolescents were more likely than female adolescents to use alcohol and nicotine as ways to cope with depressive symptoms (Repetto et al., 2004, 2005). Thus, more intervention efforts may be needed for male youth’s co-use of alcohol and nicotine. Particularly, we should equip high risk youth with better coping strategies than self-medication.

Several limitations of the study should be noted. First, our findings may not be generalizable to other minority populations because our sample consisted of predominantly Black youth. We elected not to conduct comparison between Black and the other racial group (17% White; 3% mixture) because the sample size of the latter was very small and also the recruitment protocol was not based on race but on academic achievement. Second, our sample included ninth graders with grade point average (GPA) of 3.0 or lower so the results may not be generalizable to all youth. Yet, by the twelfth grade, the range of GPA was more normal in distribution. Third, our sample had higher lifetime prevalence rates of substance use relative to the general young adult population. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to youth at lower risk. Fourth, we relied on self-report data, but this is common for this type of research. It is notable, however, that the substance use information was collected in a paper and pencil survey after the main interview was completed so may have been less influenced by interviewer effects.

These limitations notwithstanding, this study has made several significant contributions. First, the longitudinal design of FAS allows us to characterize the developmental trajectories of multiple substance use among high risk youth from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Second, we are able to take advantage of the annual data collection during this critical developmental period to provide prospective data on the timing of substance use onset. This is a unique contribution as the field has mostly relied on retrospective data of onset ages of which the accuracy is a major concern, especially for individuals who have been using the substance for some years prior to data collection. Third, the high percentage of Black youth makes the FAS sample unique because the few large scale longitudinal studies on the risk and protective factors of substance abuse include predominantly White samples.

Highlights.

Females were at risk for increasing nicotine use across time.

Early onset of nicotine and marijuana use added risk for heavy drinking.

Higher consumption of nicotine and marijuana contributed to heavy drinking.

The effect of nicotine use quantity on heavy drinking was greater among males.

Acknowledgements

Role of Funding Sources

Funding for this study was provided by NIAAA Grant K01 AA016591 and NIDA Grant R01 DA007484. NIAAA and NIDA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

MAZ designed the study and obtained the funding for data collection. JEH and HH coordinated data collection and data management. AB and AD conducted literature review and statistical analysis. AB wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg J. Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: The impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Berg N, Kiviruusu O, Karvonen S, Kestilä L, Lintonen T, Rahkonen O, Huurre T. A 26-year follow-up study of heavy drinking trajectories from adolescence to mid-adulthood and adult disadvantage. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2013;48:452–457. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomo YA, Bowes G, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Patton GC. Teenage drinking and the onset of alcohol dependence: A cohort study over seven years. Addiction. 2004;99:1520–1528. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews F, He J, Hodge C. Adolescent cortical development: A critical period of vulnerability for addiction. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2007;86:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Metrik J, McCarthy DM, Frissell KC, Applebaum M, Brown SA. Progression into and out of binge drinking among high school students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:341–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Li T, Grant BF. A prospective study of risk drinking: At risk for what? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, et al. Evaluating the drug use “gateway” theory using cross-national data: consistency and associations of the order of initiation of drug use among participants in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;108:84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Rigotti NA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, McNeill AD, Coleman M, Wood C. Development of symptoms of tobacco dependence in youth: 30 month follow up data from the DANDY study. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:228–235. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasen M, Kjær SK, Munk C, Nygård M, Sparén P, Tryggvadottir L, Grønbæk M. The relationship between age at drinking onset and subsequent binge drinking among women. European Journal of Public Health. 2009;19:378–382. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA. Psychological distress, substance use, and HIV/STI risk behaviors among youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:514–527. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9524-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Yi H, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Research & Health. 2006;29:162–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenzel L. Multivariate analyses of predictors of heavy episodic drinking and drinking-related problems among college students. Journal of College Student Development. 2005;46:126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: Early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrhelik R, Duncan A, Lee M, Stastna L, Furr-Holden CM, Miovsky M. Sex specific trajectories in cigarette smoking behaviors among students participating in the unplugged school-based randomized control trial for substance use prevention. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1145–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutma L, Eccles J, Peck S, Malanchuk O. The influence of family relations on trajectories of cigarette and alcohol use from early to late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison ER, McKee SA. Non-daily smoking predicts hazardous drinking and alcohol use disorders in young adults in a longitudinal U.S. sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison ER, Desai RA, McKee SA. Nondaily smoking and alcohol use, hazardous drinking, and alcohol diagnoses among young adults: Findings from the NESARC. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:2081–2087. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, White HR, Chung I, Hawkins J, Catalano RF. Early adult outcomes of adolescent binge drinking: Person- and variable-centered analyses of binge drinking trajectories. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:892–901. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Schulenberg JE. Conjoint developmental trajectories of young adult substance use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:723–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Cooper M, Wood PK. Adolescent alcohol and tobacco use: Onset, persistence and trajectories of use across two samples. Addiction. 2002;97:517–531. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis BH, Power CC, Manor OO. Adolescent drinking level and adult binge drinking in a national birth cohort. Addiction. 2005;100:543–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennison K M. The short-term effects and unintended long-term consequences of binge drinking in college: A 10-Year follow-up study. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:659–684. doi: 10.1081/ada-200032331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Costa FM, Krueger PM, Turbin MS. A developmental study of heavy episodic drinking among college students: The role of psychosocial and behavioral protective and risk factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:86–94. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychological development: a longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D. Stages in adolescent involvement in drug use. Science. 1995;190:912–914. doi: 10.1126/science.1188374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisdahl K, Gilbart E, Wright N, Shollenbarger S. Dare to delay? The impacts of adolescent alcohol and marijuana use onset on cognition, brain structure, and function. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2013;4:1–19. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech R, Koester S. Trends in U.S., past-year marijuana use from 1985 to 2009: An age– period–cohort analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;124:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morral AR, McCaffrey DF, Paddock SM. Reassessing the marijuana gateway effect. Addiction. 2002;97:1493–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analysis: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra GR, O'Neill SE, Sher KJ. Reliability of self-reported age of substance involvement onset. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:211–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen T, Lyyra A, Pulkkinen L. Age of onset of drinking and the use of alcohol in adulthood: A follow-up study from age 8–42 for females and males. Addiction. 2005;100:652–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetto P, Caldwell C, Zimmerman M. A longitudinal study of the relationship between depressive symptoms and cigarette use among African American adolescents. Health Psychology. 2005;24:209–219. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetto P, Zimmerman M, Caldwell C. A longitudinal study of the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use in a sample of inner-city black youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:169–178. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson C, Memetovic J, Ratner P, Johnson J. Examining gender differences in emerging tobacco use using the Adolescents' Need for Smoking Scale. Addiction. 2011;106:1846–1854. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossow I, Kuntsche E. Early onset of drinking and risk of heavy drinking in young adulthood—A 13-year prospective study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:E297–E304. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SA, Zimmerman MA. Association of interpersonal violence with self-reported history of head injury. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1074–1079. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/2k10nsduh/2k10results.htm#TabC-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Shiyko M, Li R, Li Y, Dierker L. A time-varying effect model for intensive longitudinal data. Psychological Methods. 2012;17:61–77. doi: 10.1037/a0025814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Kirisci L, Reynolds M, Clark DB. Predictors of marijuana use in adolescents before and after licit drug use: examination of the gateway hypothesis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:2134–2140. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorner ED, Jaszyna-Gasior M, Epstein DH, Moolchan ET. Progression to daily smoking: Is there a gender difference among cessation treatment seekers? Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:829–835. doi: 10.1080/10826080701202486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Martino SC, Klein DJ. Substance use trajectories from early adolescence to emerging adulthood: A comparison of smoking, binge drinking, and marijuana use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wichstrom L. The impact of pubertal timing on adolescents’ alcohol use. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Tan X, Li R, Wagner A. TVEM (time-varying effect model) SAS macro suite users' guide(Version 2.1.0) University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State; 2012. [Google Scholar]