Abstract

Although web-based treatments have significant potential to assess and treat difficult to reach populations, such as trauma-exposed adolescents, the extent that such treatments are accessed and used is unclear. The present study evaluated the proportion of adolescents who accessed and completed a web-based treatment for post-disaster mental health symptoms. Correlates of access and completion were examined. A sample of 2,000 adolescents living in tornado-affected communities was assessed via structured telephone interview and invited to a web-based treatment. The modular treatment addressed symptoms of PTSD, depression, and alcohol and tobacco use. Participants were randomized to experimental or control conditions after accessing the site. Overall access for the intervention was 35.8%. Module completion for those who accessed ranged from 52.8% to 85.6%. Adolescents with parents who used the Internet to obtain health-related information were more likely to access the treatment. Adolescent males were less likely to access the treatment. Future work is needed to identify strategies to further increase the reach of web-based treatments to provide clinical services in a post-disaster context.

Keywords: Adolescents, Internet interventions, traumatic stress, natural disaster

Adolescents exposed to natural disasters are at high risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Garrison et al., 1995; La Greca, Silverman, Vernberg, & Prinstein, 1996), depression (Kar & Bastia, 2006; Warheit, Zimmerman, Khoury, Vega, & Gil, 1996), use of tobacco (Parslow & Jorm, 2006) and alcohol products (Reijneveld, Crone, Verhulst, & Verloove-Vanhorick, 2003; Rohrbach, Grana, Vernberg, Sussman, & Sun, 2009). The ability of organized care settings to render treatment to adolescents with such diagnoses is impaired after a natural disaster, however (Self-Brown, Anderson, Edwards, & McGill, 2013). In a post-disaster environment, most agencies are focused on the basic and immediate needs of those affected. As a result, potentially long-term needs, such as psychological issues, are not well addressed. Such challenges are especially problematic in rural and nonurban locations because there are typically fewer available resources (Norris, 2002; West, Price, Gros, & Ruggiero, 2013). Adolescents with post-disaster mental health difficulties are unlikely to be identified and receive treatment as a result.

Alternative modalities of service delivery, such as the Internet, have significant potential to address the mental health needs of adolescents, especially those in nonurban and rural areas. There are several strengths to web-based treatments. Nearly all (95%) American adolescents use the Internet, and many use it to obtain health information (Madden, Lenhart, Duggan, Cortesi, & Gasser, 2013). Web-based treatments can be delivered at no cost to the end-user beyond fees associated with Internet access. In the immediate aftermath, most disaster relief focuses on restoring basic services to the affected community including electricity and Internet access. Therefore, it is likely that most households will have access to the Internet in the period shortly after a disaster. Web-based treatments are effective at treating post-trauma symptoms, although the majority of research has focused on adults (Amstadter, Broman-Fulks, Zinzow, Ruggiero, & Cercone, 2009). Provision of web-based treatments from local or national service agencies after a disaster may improve the quality of care offered and reduces the burden placed on an individual care organization.

Despite the proposed benefits, the reach of web-based treatment to disaster-affected adolescents in urban and rural areas is unknown. Reach is defined as the extent that a given population will engage with and complete an available intervention (Koepsell, Zatzick, & Rivara, 2011). Applied to the current problem, not all adolescents who are given access will engage in and benefit from a post-disaster web-based treatment. Prior work with web-based treatments with adolescents for depression and anxiety reported completion rates from 30% to 62% (Calear, Christensen, Mackinnon, Griffiths, & O'Kearney, 2009; O'Kearney, Gibson, Christensen, & Griffiths, 2006; O'Kearney, Kang, Christensen, & Griffiths, 2009). A study with disaster-affected adults reported that 52% of a population-based sample accessed a multicomponent web-based treatment, and 27% completed at least one component (Price, Gros, McCauley, Gros, & Ruggiero, 2012). Understanding rates of access, completion and variables associated with each of these behaviors is therefore a critical step towards informing service agencies about the reach of web-based treatments (Klopper, Schweinle, Ractliffe, & Elhai, 2014).

The behavioral model of health services use offers a framework with which to identify factors associated with access and completion of web-based treatments (Andersen, 2008). The model posits that variables associated with use of services fall into three domains. The first domain, predisposing factors, includes the social environment, demographic information, and cultural perspectives. The second, enabling factors, includes the availability of resources to the individual as well as the financial means to obtain healthcare. The third, evaluative need, is an individual's need for health services based on objective criteria regarding their general health, functioning, and symptom severity.

Prior work with adolescents identified the predisposing factors of gender and environment in which the intervention was delivered as most relevant to completion of a web-based treatment (Neil, Batterham, Christensen, Bennett, & Griffiths, 2009). A second study determined that the predisposing factors (more education, younger age) and enabling factors (having used the Internet to obtain health information) were associated with an increased likelihood for access of a web-based intervention among disaster affected adults (Price et al., 2012). This study also found the predisposing factor of prior use of mental health treatment was most relevant to completion. Interestingly, perceived need was largely unrelated to access and completion in both samples, which calls into the question the role of symptoms in motivating individuals to seek web-based care.

In order for agencies to appropriately implement and disseminate web-based treatments with adolescents in a post-disaster context, additional research is needed to understand the factors associated with access and completion. Disaster-affected adolescents may be less likely to utilize web-based treatments due to disruptions in roles, routines, and relationships, as well as competing demands after a disaster (e.g., addressing basic needs associated with property damage, physical health, and displacement). Second, few studies have examined predictors of accessing treatment because of the complicated methodology required to answer such questions. A population must first be identified and data collected before the treatment is available. All participants are then given access, yet only a subset will take advantage of the treatment. The majority of prior work either makes the treatment available to the general public or targets a specific population. Studies open to the general public are unable to describe the overall sample size or specific characteristics of the participants who were aware of but chose not to access the treatment. Alternatively, studies that use a targeted population, such as in a school setting, offer participants dedicated time and encouragement. The latter approach is likely to overestimate the proportion of the sample that accessed the intervention.

The present study sought to determine the proportion of adolescents, located in nonurban and urban areas, affected by tornados that accessed and completed a web-based treatment. Adolescents were first assessed via the telephone for potential predictors and then invited to access the website in a naturalistic setting (e.g., their homes). Based upon prior literature with disaster-exposed adults (Price, Davidson, Andrews, & Ruggiero, 2013; Price et al., 2012), it was estimated that 40% of the sample would access the website. Consistent with the behavioral model of health services use, it was hypothesized that predisposing factors and enabling factors would be most relevant to access. Specifically, the predisposing factors of female gender and the enabling resource of regularly using the Internet to access health related information would predict access and completion. Perceived need factors including symptoms of PTSD, depression, tobacco use, and alcohol use were also explored given their theoretical relevance.

Method

A population-based sample of disaster-affected adolescents was recruited. Address-based sampling was used to recruit 2,000 adolescents from Alabama and Missouri. Specific regions were targeted using the coordinates of areas exposed to a series of tornados that occurred 4 months prior the start of recruitment. Census block IDs were assigned to the radii around each coordinate (e.g., 0.5 mile, 2 miles) to serve as sampling strata. Households were recruited by phone or via mail. Exclusion criteria included residence in an institutional setting, households with neither a landline telephone nor cellphone, lack of home Internet access, lack of children aged 12-17 years, and non-English speakers. Budget restrictions precluded translating the intervention into other languages. The overall cooperation rate, calculated according to the American Association for Public Opinion Research industry standards (i.e., [number screened] divided by [number screened + screen-outs + unknown eligibility]), was 61%. After a complete description of the study was provided, verbal informed consent was obtained from parents and adolescents over the phone.

Households with multiple eligible adolescents had one selected at random. After the baseline interview, families were given access to the website via a unique login account. Adolescents were randomized to the intervention or to a control condition after they accessed the website. Randomization occurred in a 3:1 (experimental:control) allocation. Families were compensated $25 for their participation. Adolescents were contacted via telephone 4 months after their baseline interview to obtain additional feedback.

Participants

The sample contained 2,000 adolescents (M age=14.5, SD=1.7). The gender distribution of the sample was nearly equal (Boys: n=981, 49.0%; Girls: n=1019, 51.0%). Self-reported race was n=1251 (62.5%) White, n=451 (22.6%) Black, n=75 (3.8%) other, and n=223, 11.1% declined to answer; n=54 (2.7%) reported Hispanic ethnicity. Most households had partnered parents (n=1469, 73.4%). Median annual income was between $40,000 and $60,000; n=1422 (71.1%) of parents reported some college education. One third of the sample reported living in a rural area (33.9%), 61.4% reported living in an urban area, and 4.5% reported living an urban cluster according to US census information based on zip code.

Measures

A structured baseline interview was administered to the adolescent and a designated parent to assess demographics, disaster impact, and post-disaster mental health functioning. Highly trained interview staff using Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviews (CATI) conducted the phone interviews. CATI maximized the efficiency of the interview process by allowing for specific skip patterns and reducing missing data.

Disaster Exposure

The operationalization of disaster exposure was based on an interview used in prior research (Acierno et al., 2007). Disaster exposure was measured with 9 binary items that assessed if the participant was physically present for the tornado or injured by the tornado. Additional questions asked if the tornado caused the participant to be concerned about others, displaced from their home, or lost a pet. Lack of access to electricity, water, clean clothing, and food for at least one week was also assessed.

Mental Health

Parent mental health was assessed with the Kessler 6 (K6), a brief self-report survey assessing depression and anxiety (Cairney, Veldhuizen, Wade, Kurdyak, & Streiner, 2007; Kessler et al., 2002). Internal consistency for the K6 in the present study was good (α=0.86). Adolescent mental health was assessed with a structured interview that was validated in prior epidemiologic studies with national samples (Kilpatrick & Acierno, 2003; Resnick, Kilpatrick, Dansky, Saunders, & Best, 1993). The interview yielded dichotomous outcomes indicating whether the participant met criteria for PTSD since the tornado, depression since the tornado, had ever used alcohol, and had ever smoked cigarettes.

Internet use for health

Internet use for obtaining health-related information among parents was assessed with the question “Have you ever looked on the Internet for information about a specific disease or medical problem?” Adolescents were asked separately if they had ever looked online for information about physical health, mental health, cigarettes, or substance use.

Intervention

The intervention, called “Bounce Back Now” (BBN) was modular such that participants accessed the content modules based on their preference. Adolescents could enter up to four separate modules that offered strategies to reduce symptoms of PTSD, depression, cigarette use, and alcohol use. After entering a module, adolescents were administered a screener that assessed the symptoms targeted by the module. For example, the depression module asked about the symptoms of depression. Participants who endorsed 2 symptoms of depression, 3 symptoms of PTSD, or any tobacco use were identified as a screen-in and encouraged to complete the respective module. Participants with a negative screen were given the option to complete or leave the module. All participants were given the alcohol module regardless of screener results.

Content for each module was consistent with evidence-based treatments for the respective conditions. The PTSD module provided psychoeducation and guidelines on how to complete exposures to trauma related stimuli, reduce avoidance, and develop coping strategies to manage anxiety (Deblinger et al., 1990; Pynoos, 1993; Ruggiero et al., 2001). The mood module featured behavioral activation strategies, which have shown promise as easily understood and efficacious in the treatment of depression (Hopko, Lejuez, Ruggiero, et al., 2003; Jacobson et al., 1996; Ruggiero et al., 2007). The tobacco and alcohol modules used brief motivational-enhancement and cognitive-behavioral strategies (Dennis et al., 2004; Waldron & Kaminer, 2004). These strategies are evidence based and intended to address the needs of adolescent populations such as teaching skills to: (a) refuse substance abuse offers from peers; (b) establish a positive family and peer network that is supportive of the youth abstaining from use; (c) develop a plan for positive, enjoyable activities to replace substance use-related activities, and (d) cope with stressful and/or high-risk situations (Sampl & Kadden, 2001). Content was displayed through various media to enhance engagement with the intervention (e.g., text, graphics, animations, videos, quizzes).

Control condition content included questions to assess knowledge of a given disorder without providing intervention components or feedback. Control participants did not receive the interactive components (e.g., graphics, videos, activities within the module) or educational materials that were part of the experimental condition. As a result, the control condition was considerably less time-consuming for participants.

Definitions of access and completion (Eysenbach, 2005)

Participants who started a module were considered to have “accessed” the module. Participants who then reached the last page of a module were considered to have “completed” the module.

Data Analytic Plan

An overall rate of access was calculated by dividing the number of adolescents who accessed at least one module by the total N. Module-specific access rates were calculated by dividing the number of participants who accessed a given module by the total N. Rates of completion were calculated by dividing the number of adolescents who completed the module by the total number of participants that accessed the module. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to identify predictors of access and completion (Zeger, Liang, & Albert, 1988) using nested models (Singer & Willett, 2003). An initial model containing all hypothesized predictors was first fitted. Retention of predictors was evaluated in a systematic fashion through change in the deviance statistic. Variables within a category (demographics, Internet access, disaster variables, parent mental health, and adolescent mental health) were removed from smallest to largest odd's ratio (OR). Separate models were evaluated for each module.

Results

Rates of Access and Completion

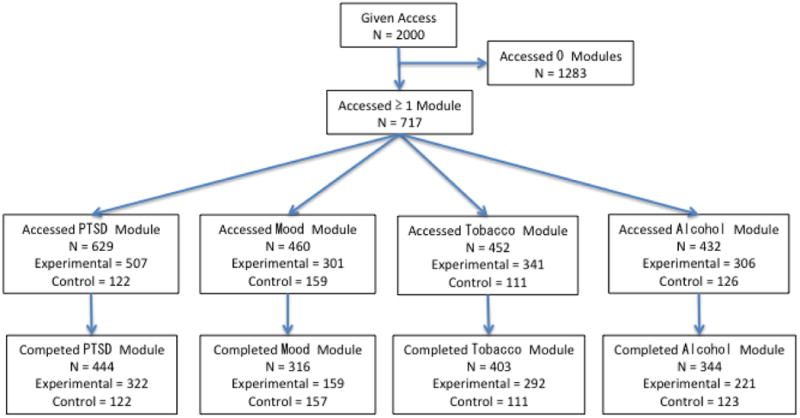

Figure 1 indicates the proportion of the sample that accessed and completed the intervention. Invitations to access the website were sent to 2000 adolescents. More than 1 in 3 adolescents chose to access the website (n=717; 35.8%). Of those who accessed the website, n=550 were randomized to the experimental condition and n=167 were randomized to the control condition. Participants in the experimental condition accessed M=2.65, SD=1.28 modules and those in the control condition accessed M=3.02, SD=1.27 modules. The overall completion rate, defined as completing at least 1 module, was 73.2% (n=403) for the experimental condition and 99.4% (n=166) for the control condition.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram demonstrating the rates of access and completion in the total sample.

Predictors of access

Of the 2000 participants invited to access the website, a subset (N=1765) had sufficient data to be included in a model predicting access to the website. The excluded participants (n=235) refused or declined to answer baseline interview questions and thus were considered to have not missing at random data. Mental health, disaster exposure, demographics, and service use variables were included in the model. Descriptive statistics for all variables included in the model are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of predictors included in the models assessing access and completion.

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | %1 |

| Depression since tornado | 162 | 8.1 |

| PTSD since tornado | 153 | 8.0 |

| Used alcohol in past month | 170 | 8.5 |

| Tried cigarettes | 273 | 13.7 |

| Loss of sentimental objects | 210 | 10.5 |

| Loss Pet | 81 | 4.0 |

| Left home for > 1 day | 600 | 30.1 |

| Present for tornado | 1806 | 90.6 |

| Injured from tornado | 53 | 2.7 |

| Concerned for friends and family | 1495 | 74.8 |

| Lost electricity for 1 week | 462 | 23.1 |

| Lost clean clothing for 1 week | 125 | 6.3 |

| Lost food for 1 week | 95 | 4.8 |

| Lost drinking water for 1 week | 86 | 4.3 |

| Male gender | 981 | 49.0 |

| Hispanic | 54 | 3.0 |

| Black | 451 | 25.4 |

| Parents partnered | 1469 | 73.5 |

| Teen owns mobile device | 1359 | 68.2 |

| Teen looked for health info online | 731 | 36.6 |

| Teen looked for mental health info online | 292 | 14.7 |

| Teen looked for tobacco or alcohol info online | 154 | 7.7 |

| Parents looked for health info online | 1385 | 69.4 |

|

| ||

| M | SD | |

|

| ||

| Teen Age | 14.5 | 1.7 |

| Parent Age | 45.0 | 9.3 |

| Parent Kessler 6 | 5.4 | 5.2 |

Note:

Percentage based on valid cases for a given variable. Total N =2000.

The analysis examining predictors of access included both experimental and control conditions because there were no differences in study procedures prior to access (Table 2). The final model predicting PTSD module access suggested the access rate was higher among adolescents who met criteria for PTSD (OR=1.44, p=0.04), reported drinking alcohol in the past month (OR=1.71, p<0.01), had parents who used the Internet to obtain health information (OR=1.38, p=0.01), and had more educated parents (OR=1.16, p=0.01). Alternatively, adolescents who had older parents (OR=0.99, p=0.05), were male (OR=0.81, p=0.03), and had tried cigarettes (OR=0.56, p<0.01) were less likely to access this module.

Table 2. Predictors of module access.

| 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| PTSD | OR | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Met criteria for PTSD | 1.44* | 1.01 | 2.05 |

| Used alcohol in past month | 1.71** | 1.16 | 2.52 |

| Tried cigarettes | 0.56** | 0.40 | 0.79 |

| Parent age | 0.99* | 0.98 | 1.00 |

| Parent education | 1.16** | 1.04 | 1.31 |

| Teen Male | 0.81* | 0.66 | 0.98 |

| Parents looked for health info online | 1.38** | 1.01 | 1.74 |

|

| |||

| Mood | |||

|

| |||

| Tried cigarettes | 0.60** | 0.43 | 0.85 |

| Parent education | 1.16* | 1.02 | 1.31 |

| Teen Male | 0.72** | 0.58 | 0.89 |

| Parents looked for health info online | 1.40** | 1.08 | 1.80 |

|

| |||

| Alcohol | |||

|

| |||

| Used alcohol in past month | 1.54* | 1.01 | 2.35 |

| Tried cigarettes | 0.64* | 0.44 | 0.93 |

| Without clean clothes for > 1 week after tornado | 0.40** | 0.21 | 0.75 |

| Parent education | 1.21** | 1.06 | 1.37 |

| Teen Male | 0.75** | 0.60 | 0.94 |

| Teen searched online for info about substances | 1.50* | 1.02 | 2.21 |

|

| |||

| Smoking | |||

|

| |||

| Used alcohol in past month | 1.75** | 1.15 | 2.66 |

| Tried cigarettes | 0.51** | 0.35 | 0.74 |

| Teen Male | 0.74** | 0.60 | 0.92 |

| Without food for > 1 week after tornado | 0.40** | 0.20 | 0.80 |

Note: Sample size was N =1765 based on the availability of baseline data.

=p < 0.05.

=p < 0.01.

The final model predicting mood module access suggested that the access rate was higher among adolescents with parents who used the Internet to obtain health information (OR=1.40, p=0.01) and whose parents had more education (OR=1.16, p=0.02). Similar to PTSD, adolescents who had tried cigarettes (OR=0.60, p<0.01) and males (OR=0.72, p<0.01) were less likely to access the mood module.

The final model predicting alcohol module access suggested that access rate was higher among adolescents who used alcohol in the past month (OR=1.54, p=0.05), had parents with more education (OR=1.21, p<0.01), and used the Internet to obtain information about substances (OR=1.50, p=0.04). Adolescents who tried cigarettes (OR=0.64, p=0.02), were male (OR=0.75, p=0.01), and were without clean clothing for at least 1 week (OR=0.40, p<0.01) were less likely to access the module.

The final model predicting tobacco module access suggested that access rate was lower for those who were without food or clothing for more than 1 week (OR=0.40, p=0.01), tried tobacco (OR=0.51, p<0.01), and were male (OR=0.74, p=0.01). Those who drank alcohol in the past month were more likely to access the smoking module (OR=1.75, p=0.01).

Predictors of completion

Similar models were constructed to identify predictors of completion in the experimental condition. Those who screened into the PTSD module by reporting 2 or more symptoms of PTSD (OR=6.99, p<0.01) were more likely to complete this module. However, adolescents who had used the Internet to look for mental health related information (OR=0.46, p=0.02) and those who lost sentimental objects (OR=0.45, p=0.03) were less likely to complete this module. The final model predicting mood module completion in the experimental condition suggested that those who screened into the module by endorsing 3 or more symptoms of depression were more likely to complete (OR=17.86, p <0.01). The final model predicting alcohol module completion in the experimental condition suggested that those who tried cigarettes were less likely to complete the alcohol module (OR=0.40, p=0.02). There were no significant predictors associated with completing the tobacco module. Models examining predictors of module completion for the control group were not tested because of low rates of dropout for these modules (n=0-3).

Follow up data

At the 4-month follow up interview, n=288 of those who did not access the website were contacted and asked about their lack of engagement. The most commonly endorsed reason was that they were “too busy” (n=212). Relatively few participants had concerns about security (n=24) or privacy (n=11). Of those who accessed the website, n=280 of those in the experimental condition were contacted at 4-month follow-up and asked about their experience. The majority of this subsample found the website easy to use (n=214) and would recommend it to others (n=207). The majority (n=182) of the experimental condition spent between 30 and 90 minutes on the site with a notable proportion (n=71) spending >90 minutes on the site.

Discussion

This study addressed an important, and unanswered question: if we build a web-based resource to address adolescents' disaster mental health problems, will they come? The literature has shown that 3 in 4 youth with significant mental health symptoms after a disaster do not receive mental health care to address their needs (Fairbrother, Stuber, Galea, Pfefferbaum, & Fleischman, 2004). Alternative solutions are needed to increase access to needed care and to help the health care system address demand in urban and rural areas. Web-based approaches are scalable and sustainable and may offer significant benefit.

Results suggested that more than 1 in 3 adolescents accessed the web-based treatment and more than 1 in 5 completed it. Given that the resource was available to each participant for 4-months and that approximately 34% resided in nonurban areas, these proportions provide empirical support that a web-based treatment can achieve high penetration in a relatively brief period. These data are among the first to be reported on use of such an intervention with a large pre-specified population of adolescents. Module-specific completion ranged from 52.8%-85.6%, which is consistent with prior adolescent and adult studies of web-based treatments (Neil et al., 2009; Price et al., 2012).

Despite these promising numbers, there is considerable room for improving engagement with web-based treatments in adolescents. Access and use may benefit from the inclusion of social networks (Mohr, Cuijpers, & Lehman, 2011) or interactive content including games (Brockmyer et al., 2009). Social connections buffer against mental health symptoms (Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003), enhance treatment (Price, Gros, Strachan, Ruggiero, & Acierno, 2013), and are hypothesized to increase use of technology-based treatments (Mohr et al., 2011). Integrating social networks may increase use, especially for adolescent boys.

Organized care agencies could use a web-based treatment as part of the initial response to a disaster to conduct population-level assessments and treatment in remote areas. Such a strategy may successfully treat mild to moderate symptoms in adolescents and identify those with severe symptoms. Those identified with severe symptoms could be referred for follow-up with a local care agency. This strategy could involve the coordination of state and national agencies in that a larger group deploys the intervention and is able to refer symptomatic adolescents to local providers. Such a strategy is likely to use limited resources efficiently and result in improved mental health at the population level (Draper & Ghiglieri, 2011).

Using the behavioral model of health services use as a framework, our findings identified the subpopulations that web-based treatments are most likely to reach. Consistent with prior work, the predisposing factor of gender and the enabling factor of parental use of the Internet were most strongly associated with access (Donkin et al., 2011; Neil et al., 2009; Price, Davidson, et al., 2013; Price et al., 2012). Parents who use the Internet may be more likely to actively encourage their children to seek health-related information online. Care agencies should develop strategies to access households who may not regularly use the Internet via a laptop or desktop computer. Therefore, a multi-method strategy in which mobile devices or paper-based approaches are used is likely necessary to reach different segments of the disaster-affected population.

The results suggest that adolescent boys (33.1%) were less likely to access the website that girls (38.5%). These proportions, however, were relatively comparable across the genders and gender was unrelated to completion. The discrepancy between boys and girls was less than what is observed in studies of access of traditional mental health services (Wang et al., 2005). Adolescent boys are more likely to experience mental health stigma, which is associated with a decreased willingness to use mental health services (Chandra & Minkovitz, 2006). The increased privacy offered by web-based treatments may facilitate their willingness to use this treatment.

Importantly, evaluative need variables were inconsistently related to treatment access. Meeting criteria for PTSD since the tornado according to the baseline interview was associated with an increased likelihood that an adolescent would access the PTSD module. However, this was not the case for depression and access of the mood module. It is often assumed that those with increased mental health symptoms will self-select into treatments when given the opportunity, but empirical support for this has been mixed (Amstadter, McCauley, Ruggiero, Resnick, & Kilpatrick, 2008; Price, Davidson, Ruggiero, Acierno, & Resnick, 2014). To address this limitation, another study identified personalized feedback as a method to enhance access in trauma-exposed samples (Price, Ruggiero, et al., 2014). For example, an adolescent avoiding conversations about the disaster could be given specific social skills training. Providing tailored feedback to high-risk adolescents, perhaps through population-level assessments, may increase the likelihood of accessing subsequent services.

There were few consistent predictors of treatment completion. This may suggest that once adolescents access an intervention, they are likely to complete the content. Such content may be especially useful for those who are highly symptomatic given that endorsing sufficient symptoms to “screen in” to the mood and PTSD modules was associated with a higher rate of completion. The lack of significant predictors associated with completion may also reflect the use of completion, defined as reaching the end of a module, as a poor indicator of engagement with web-based content. Better indicators may include time spent per page, the extent of interaction with the content, and knowledge retained from interactive content. Such indicators are also more likely to be associated with response to the treatment (Kiluk et al., 2011). Future work is encouraged to examine Internet-based treatment data at this level.

The present study had several limitations. First, the website was intended to be used as secondary prevention but was made available to adolescents months after the disaster. This delay may have allowed a substantial portion of the individuals to recover naturally and thus render the intervention unnecessary. Future research that deploys this approach in the immediate aftermath of a disaster is needed. A first step toward this process is developing expedited procedures that allow studies to rapidly receive approval from the necessary regulatory bodies. Second, the current study did not include measures that were directly related to Internet use such as familiarity with technology, estimated time spent on the Internet, and frequent tasks completed on the Internet. Third, adolescents received monetary compensation for participating in the study, which may have inflated overall adherence rates. Fourth, the population-based sample was not highly symptomatic, which may have reduced the level of perceived need for this intervention. However, the use of a population-based sample is a relative strength of this study, as it provides an estimate of use rates should these approaches be widely disseminated. Finally, the present study was unable to obtain detailed data on participant use of the website including time spent per page, clicks per activity, and time to completion. Examining such use variables is likely necessary to understand patient behavior on web-based treatments and improve the quality of treatment.

The data from the current study provide empirical support for the quick and broad dissemination of web-based treatments. Such approaches can be part of a multifaceted approach that uses mobile technologies, telehealth, and traditional services in a stepped care approach (Price, Yuen, et al., 2013). Research on access rates, completion rates, usability, and effectiveness of such approaches, particularly for disaster-affected adolescents, will inform dissemination strategies that improve both their appeal and effectiveness.

Table 3. Predictors of module completion in the experimental condition.

| 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 1PTSD | OR | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Loss of sentimental objects | 0.45* | 0.22 | 0.94 |

| Looked online for mental health information | 0.46* | 0.24 | 0.88 |

| Endorsed > 2 PTSD symptoms within the module | 6.99** | 4.18 | 11.69 |

|

| |||

| 2Mood | |||

|

| |||

| Endorsed > 3 symptoms within the module | 17.86** | 6.26 | 50.94 |

|

| |||

| 3Alcohol | |||

|

| |||

| Tried cigarettes | 0.40* | 0.18 | 0.88 |

Note:

Sample excluded n=10 participants who did not have sufficient baseline data; Sample size = 434.

Sample excluded n=41 participants who did not have sufficient baseline data; Sample size = 260.

Sample excluded n=78 participants who did not have sufficient baseline data; Sample size = 263.

=p < 0.05.

=p < 0.01.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None for any author

References

- Acierno R, Ruggiero KJ, Galea S, Resnick HS, Koenen K, Roitzsch J, Kilpatrick DG. Psychological Sequelae Resulting From the 2004 Florida Hurricanes: Implications for Postdisaster Intervention. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(Supplement_1):S103–S108. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, Broman-Fulks J, Zinzow H, Ruggiero KJ, Cercone J. Internet Based Interventions for Traumatic Stress-Related Mental Health Problems: A Review and Suggestion for Future Research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(5):410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, McCauley JL, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG. Service Utilization and Help Seeking in a National Sample of Female Rape Victims. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC) 2008;59(12):1450–1457. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM. National Health Surveys and the Behavioral Model of Health Services Use. Medical Care. 2008;46(7):647–653. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817a835d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmyer JH, Fox CM, Curtiss KA, McBroom E, Burkhart KM, Pidruzny JN. The development of the Game Engagement Questionnaire: A measure of engagement in video game-playing. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(4):624–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cairney J, Veldhuizen S, Wade TJ, Kurdyak P, Streiner DL. Evaluation of 2 measures of psychological distress as screeners for depression in the general population. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;52(2):111–120. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calear AL, Christensen H, Mackinnon A, Griffiths KM, O'Kearney R. The YouthMood Project: A cluster randomized controlled trial of an online cognitive behavioral program with adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(6):1021–1032. doi: 10.1037/a0017391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Minkovitz CS. Stigma starts early: Gender differences in teen willingness to use mental health services. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(6):754.e1–754.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkin L, Christensen H, Naismith SL, Neal B, Hickie IB, Glozier N. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Adherence on the Effectiveness of e-Therapies. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011;13(3):e52. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper C, Ghiglieri M. Stepped care and e-health. Springer; 2011. Post-traumatic stress disorder. Computer based stepped care: Practical applications to clinical problems; pp. 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2005;7(1):e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother G, Stuber J, Galea S, Pfefferbaum B, Fleischman AR. Unmet Need for Counseling Services by Children in New York City After the September 11th Attacks on the World Trade Center: Implications for Pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1367–1374. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison CZ, Bryant ES, Addy CL, Spurrier PG, Freedy JR, Kilpatrick DG. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Adolescents after Hurricane Andrew. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34(9):1193–1201. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar N, Bastia BK. Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and generalised anxiety disorder in adolescents after a natural disaster: a study of comorbidity. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2006;2(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SLT, Zaslavsky AM. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R. Mental health needs of crime victims: epidemiology and outcomes. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16(2):119–132. doi: 10.1023/A:1022891005388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Sugarman DE, Nich C, Gibbons CJ, Martino S, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. A methodological analysis of randomized clinical trials of computer-assisted therapies for psychiatric disorders: toward improved standards for an emerging field. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):790–799. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klopper JJ, Schweinle W, Ractliffe KC, Elhai JD. Predictors of mental healthcare use among domestic violence survivors in shelters. Psychological Services. 2014;11(2):134–140. doi: 10.1037/a0034960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell TD, Zatzick DF, Rivara FP. Estimating the population impact of preventive interventions from randomized trials. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;40(2):191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Prinstein MJ. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in children after Hurricane Andrew: a prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(4):712–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden M, Lenhart A, Duggan M, Cortesi S, Gasser U. Teens and Technology 2013. 2013 Mar 13; Retrieved July 20, 2013, from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Teens-and-Tech/Summary-of-Findings.aspx.

- Mohr DC, Cuijpers P, Lehman K. Supportive accountability: a model for providing human support to enhance adherence to eHealth interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011;13(1):e30. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil AL, Batterham P, Christensen H, Bennett K, Griffiths KM. Predictors of Adherence by Adolescents to a Cognitive Behavior Therapy Website in School and Community-Based Settings. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2009;11(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH. Disasters in urban context. Journal of Urban Health. 2002;79(3):308–314. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.3.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kearney R, Gibson M, Christensen H, Griffiths K. Effects of a Cognitive‐ Behavioural Internet Program on Depression, Vulnerability to Depression and Stigma in Adolescent Males: A School- Based Controlled Trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2006;35(1):43–54. doi: 10.1080/16506070500303456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kearney R, Kang K, Christensen H, Griffiths K. A controlled trial of a school-based Internet program for reducing depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26(1):65–72. doi: 10.1002/da.20507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(1):52–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parslow RA, Jorm AF. Tobacco use after experiencing a major natural disaster: analysis of a longitudinal study of 2063 young adults. Addiction. 2006;101(7):1044–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M, Davidson TM, Andrews JO, Ruggiero KJ. Access, use and completion of a brief disaster mental health intervention among Hispanics, African-Americans and Whites affected by Hurricane Ike. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2013;19(2):70–74. doi: 10.1177/1357633X13476230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M, Davidson TM, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Resnick HS. Predictors of Using Mental Health Services After Sexual Assault. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2014;27(3):331–337. doi: 10.1002/jts.21915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M, Gros DF, McCauley JL, Gros KS, Ruggiero KJ. Nonuse and dropout attrition for a web-based mental health intervention delivered in a post-disaster context. Psychiatry. 2012;75(3):267–284. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2012.75.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M, Gros DF, Strachan M, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R. The role of social support in exposure therapy for Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom veterans: A preliminary investigation. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0026244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M, Ruggiero KJ, Ferguson PL, Patel SK, Treiber F, Couillard D, Fahkry SM. A feasibility pilot study on the use of text messages to track PTSD symptoms after a traumatic injury. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M, Yuen EK, Goetter EM, Herbert JD, Forman EM, Acierno R, Ruggiero KJ. mHealth: A Mechanism to Deliver More Accessible, More Effective Mental Health Care. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2013 doi: 10.1002/cpp.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijneveld SA, Crone MR, Verhulst FC, Verloove-Vanhorick SP. The effect of a severe disaster on the mental health of adolescents: a controlled study. The Lancet. 2003;362(9385):691–696. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(6):984–991. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach LA, Grana R, Vernberg E, Sussman S, Sun P. Impact of Hurricane Rita on Adolescent Substance Use. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2009;72(3):222–237. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2009.72.3.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self-Brown S, Anderson P, Edwards S, McGill T. Child Maltreatment and Disaster Prevention: A Qualitative Study of Community Agency Perspectives. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2013;14(4):401–407. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2013.2.16206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. 1st. Oxford University Press; USA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-Month Use of Mental Health Services in the United States: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warheit GJ, Zimmerman RS, Khoury EL, Vega WA, Gil AG. Disaster Related Stresses, Depressive Signs and Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among a Multi-Racial/Ethnic Sample of Adolescents: A Longitudinal Analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1996;37(4):435–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JS, Price M, Gros KS, Ruggiero KJ. Community Support as a Moderator of Postdisaster Mental Health Symptoms in Urban and Nonurban Communities. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2013;7(05):443–451. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for Longitudinal Data: A Generalized Estimating Equation Approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(4):1049–1060. doi: 10.2307/2531734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]