Abstract

Canker caused by the Ascomycete Valsa mali is the most destructive disease of apple in Eastern Asia, resulting in yield losses of up to 100%. This necrotrophic fungus induces severe necrosis on apple, eventually leading to the death of the whole tree. Identification of necrosis inducing factors may help to unravel the molecular bases for colonization of apple trees by V. mali. As a first step toward this goal, we identified and characterized the V. mali repertoire of candidate effector proteins (CEPs). In total, 193 secreted proteins with no known function were predicted from genomic data, of which 101 were V. mali-specific. Compared to non-CEPs predicted for the V. mali secretome, CEPs have shorter sequence length and a higher content of cysteine residues. Based on transient over-expression in Nicotiana benthamiana performed for 70 randomly selected CEPs, seven V. mali Effector Proteins (VmEPs) were shown to significantly suppress BAX-induced PCD. Furthermore, targeted deletion of VmEP1 resulted in a significant reduction of virulence. These results suggest that V. mali expresses secreted proteins that can suppress PCD usually associated with effector-triggered immunity (ETI). ETI in turn may play an important role in the V. mali–apple interaction. The ability of V. mali to suppress plant ETI sheds a new light onto the interaction of a necrotrophic fungus with its host plant.

Keywords: apple Valsa canker, secreted protein, cell death, virulence factor, plant–fungus interaction

Introduction

The Apple Valsa canker fungus Valsa mali is a necrotrophic pathogen inducing severe necrosis on apple. It is the most devastating pathogen of apple in Eastern Asia, causing severe yield losses each year (Lee et al., 2006; Li et al., 2013). This pathogen preferentially infects apple although it is also aggressive to other Rosaceae woody plants such as pear, crabapple, apricot and peach (Wang et al., 2011b; Zhou et al., 2014). V. mali is considered a necrotroph that completes its life cycle on dead plant cells killed prior to or during colonization (Ke et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2015). Particularly, genes involved in plant cell wall degradation and toxin synthesis are remarkably expanded in the V. mali genome and are commonly up-regulated during infection (Ke et al., 2014; Yin et al., 2015). However, it is becoming more and more evident that interactions between necrotrophs and their hosts are considerably more complex and subtle than previously thought. Functional analysis of the V. mali genome showed that 193 secreted proteins have no known annotation, of which about 101 are V. mali-specific. Given that phytopathogens often secrete a series of proteins into the host–pathogen interface to manipulate host cell physiology and ultimately promote infection, functional verification of these secreted proteins is of particular interest for identifying potential virulence factors.

Effectors play an important role in the host–pathogen interface during infection (Giraldo and Valent, 2013; Vleeshouwers and Oliver, 2014). It is generally accepted that biotrophs actively suppress programmed cell death (PCD) of the host, whereas necrotrophs are believed to promote cell death to enhance colonization (Donofrio and Raman, 2012; Mengiste, 2012). Typically, most of the known effectors secreted by necrotrophic fungi (e.g., Parastagonospora nodorum, Pyrenophora tritici-repentis, Alternaria alternata, or Cochliobolus heterostrophus) lead to effector-triggered susceptibility (ETS) resulting in host cell death (reviewed in Wang et al., 2014). Intriguingly, the effector protein SSITL of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum can suppress the jasmonic/ethylene (JA/ET) signaling pathway mediated resistance at an early stage of infection (Zhu et al., 2013). In addition, oxalic acid secreted by S. sclerotiorum inhibits host autophagy which constitutes an effective defense response in this necrotrophic fungus–plant interaction (Kabbage et al., 2013). These evidences suggest that effectors of necrotrophic fungi may also suppress host defense responses, rather than induce cell death.

Programmed cell death triggered in plants by the pro-apoptotic mouse protein BAX physiologically resembles PCD associated with defense-related HR (Lacomme and Santa Cruz, 1999). As a result, the ability to suppress BAX-triggered PCD has proven a valuable initial screen for pathogen effectors capable of suppressing defense-associated PCD (Abramovitch et al., 2003; Dou et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011a).

As a first step toward elucidating the molecular basis for colonization of apple by V. mali, we identified and characterized the V. mali repertoire of candidate effectors. Out of 70 randomly selected candidate effector proteins (CEPs), seven were able to suppress BAX-induced PCD in Nicotiana benthamiana. Furthermore, functional characterization of VmEP1 revealed that this candidate effector is a true virulence factor of V. mali. Taken together, the candidate effectors identified here provide valuable information for the study of the V. mali–apple interaction. Suppression of effector-triggered immunity (ETI) by this necrotrophic pathogen provides new insights into the interaction of a necrotrophic fungus and its host plant.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Culture Conditions

Valsa mali strain 03–8 is a stock culture of the Laboratory of Integrated Management of Plant Diseases at the College of Plant Protection, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, PRC (Available on request). Cultures were maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium with a layer of cellophane at 25°C in the dark. Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 used for molecular cloning and agro-infiltration experiments was cultured on Luria-Bertani medium at 28°C. N. benthamiana plants were maintained at 25°C with 16 h illumination per day.

Construction of V. mali cDNA Libraries

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Shenzhen, PRC) according to the manufacturer’s protocol from (a) V. mali mycelium grown on PDA medium for 3 days, and (b) apple twigs of Malus domestica borkh. cv. ‘Fuji’ inoculated with V. mali mycelium [3 days post inoculation (dpi)]. First strand cDNA was synthesized by the RevertAidTM First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Shenzhen, PRC) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Sequence Analyses

The secretome of V. mali was obtained from the sequenced genome in our previous study (Yin et al., 2015). The Whole-Genome Shotgun project for V. mali has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession JUIY01000000. CEPs were defined as extracellular proteins with no known function (e-value > 1e–5). Cysteine content was calculated using the pepstats program from the EMBOSS package (http://emboss.bioinformatics.nl/). Markov clustering analysis was performed using tribe-MCL (Enright et al., 2002). The known effector motifs RXLR (Kale et al., 2010), [L/I]xAR (Godfrey et al., 2010), YxSL[R/K] (Saunders et al., 2012), [R/K]VY[L/I]R (Ridout et al., 2006), and [Y/F/W]xC (Dodds et al., 2009) were searched for using the fuzzpro program from the EMBOSS package. Nuclear localization signals (NLSs) were predicted with NLStradamus (Ba et al., 2009). De novo motif search was performed using MEME (Bailey et al., 2009).

Plasmid Constructs

Targeted genes were amplified from the cDNA library using high-fidelity TransStart® FastPfu DNA polymerase (TransStart, Beijing, PRC). For A. tumefaciens infiltration assays in N. benthamiana, PCR products were digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes and ligated into the PVX vector pGR106 (Giraldo and Valent, 2013). Primers used for PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1. All plasmids were confirmed by sequencing.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens Infiltration Assays

Agro-infiltration assays were carried out following the previously described procedure (Dou et al., 2008). For transient expression, A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 carrying an expression plasmid (pGR106:effector) was grown in LB medium containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml). Cells were resuspended in 10 mM MgCl2 (pH 5.6) and cell density was adjusted to an OD600 = 0.4. Bacteria were infiltrated through a little nick with a syringe to the upper leaves of 4-week-old N. benthamiana plants. A. tumefaciens cells carrying the Bax gene (pGR106:Bax) were infiltrated into the same site just subsequently, or 16 h later. As control, plants were infiltrated with A. tumefaciens carrying an empty PVX vector. Cell death symptoms were evaluated and photographed 3–4 days past infiltration. Each assay was performed in triplicate.

RNA Extraction and Transcript Level Analysis

To measure transcript level of candidate effector genes by qRT-PCR, apple tissue infected with V. mali strain 03–8 was sampled at 0, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours post inoculation (hpi). Total RNA was extracted using the RNAeasy® Plant mini kit (Qiagen, Shenzhen, PRC) following the recommended protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using an RT-PCR system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. SYBR green qRT-PCR assays were performed to analyze transcript levels. V. mali housekeeping gene G6PDH was used as endogenous control (Yin et al., 2013). Data from three biological replicates were used to calculate the mean and standard deviation. Primers used for qRT-PCR were listed in Supplementary Table S3.

Generation of VmEP1 Mutants

A typical reaction assembling three components using the hygromycin B phosphotransferase gene (hph) as a selective marker. The hph gene was amplified with primers, HPH-F (5′-GGCTTGGCTGGAGCTAGTGGAGGTCAA-3′ and HPH-R 5′-AACCCGCGGTCGGCATCTACTCTATTC-3′) from pBIG2RHPH2-GFP-GUS. The upstream (∼1,100 bp) and downstream (∼1,400 bp) flanking sequences of VmEP1 were amplified using primer pairs VmEP1-1F/2R and VmEP1-3F/4R, respectively. Then the deletion cassette was generated by double-joint PCR as described (Yu et al., 2004), using the primer pair VmEP1-CF/CR. For generating deletion mutants, the VmEP1 gene-replacement construct was transformed into protoplasts of V. mali as previously described (Gao et al., 2011). Putative deletion mutants were verified by PCR using four primer pairs (VmEP1-5F/6R, VmEP1-7F/H855R, VmEP1-H856F/8R, and H850/H852) to detect target gene (∼850 bp), upstream (∼1,100 bp), and downstream (∼1,400 bp) region, and the hph gene (∼750 bp), respectively. Subsequently, deletion mutants were confirmed by Southern blot hybridization using the DIG DNA Labeling and Detection Kit II (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers used for gene deletion are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Complementation of the ΔVmEp1 Mutant

A fragment containing the entire VmEp1 gene without the termination codon and its promoter (∼1.5 kb) was amplified with primers VmEp1-FL2-F/R (5′-cgactcactatagggcgaattgggtactcaaattggTTTATCTCAATCGCCTCGTT-3′ and 5′-caccaccccggtgaacagctcctcgcccttgctcacGTCTACCGAACATGTCTGTGG-3′), and cloned into plasmid pFL2 by the yeast gap repair approach (Bruno et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2012). The resulting construct, pFL2-VmEp1, was transformed into protoplasts of the ΔVmEp1 mutants 74# and 85#. ΔVmEp1/VmEp1 transformants were confirmed by PCR using the primer pair VmEP1-5F/6R. The ΔVmEp1/VmEp1 complemented transformants 74#-1 and 85#-1were selected for phenotypic analysis.

Vegetative Growth, Conidiation, and Pathogenicity of Mutants

Vegetative growth and conidiation was examined at three and 40 days, respectively. For our pathogenicity assay, detached apple twigs of Malus domestica borkh. cv. ‘Fuji’ were inoculated with VmEP1 deletion mutants, ΔVmEp1/VmEp1 complementation mutants, and wild type as described (Oliva et al., 2010). All treatments were performed with at least ten replicates, and all experiments were repeated three times. Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test using the SAS software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Epifluorescence Microscopy

To measure the level of colonization by the VemEP1-deletion mutants, boundary-zones (∼0.5 cm2) of inoculated leaves were sampled at 60 hpi and treated with 1 M KOH solution for 15 min at 121°C. After cooling to room temperature, the samples were washed in distilled water twice and then stained in a staining solution (0.067 M K2HPO4 + 0.05% aniline blue) according to Hood and Shew (1996). Leaf samples were examined under a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope (excitation 485 nm, dichronic mirror 510 nm, barrier 520 nm). Wild type strain 03–8 was used as control. All treatments were performed with at least five replicates, and all experiments were repeated three times.

Results

Characterization of Candidate Effector Proteins of V. mali

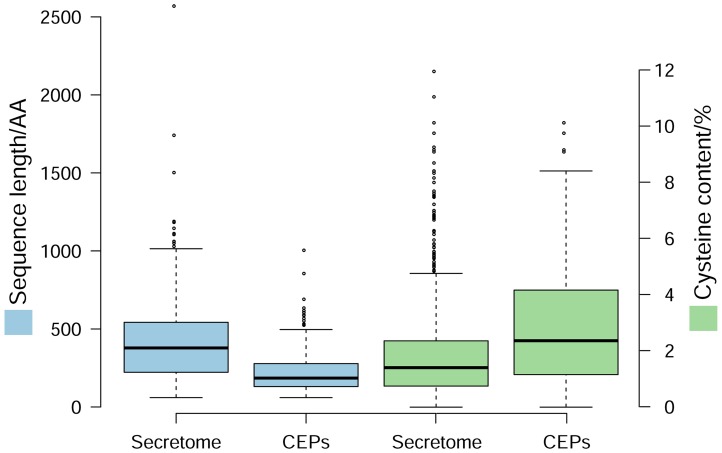

Considering that pathogen effector repertoires are typically lineage-specific, we defined CEPs as predicted extracellular proteins with no known function (e-value threshold >1e–5). Among the 779 secreted proteins predicted from the V. mali genome (Yin et al., 2015), we identified 193 CEPs, of which 101 are V. mali-specific. Analysis of amino acid sequences revealed that V. mali CEPs have several commonly known properties of effector proteins. They have shorter sequence length relative to non-CEPs, with an average of 233 amino acids, and are also cysteine rich (Figure 1). Markov clustering suggests that there is no obvious expansion of V. mali CEP families, and most families contain only one member.

FIGURE 1.

Characteristics of candidate effector proteins (CEPs) in Valsa mali. Box-plot shows sequence length and cysteine content of CEPs compared with those of the total secretome.

Search for conserved motifs in these 193 CEPs showed that 71 of them contain a total of 97 Y/F/WxC motifs, 22 contain 26 L/IxAR motifs, and seven contain a single RxLR motif each. No additional conserved motifs were identified by de novo prediction. In addition, nine CEPs are predicted to contain NLSs.

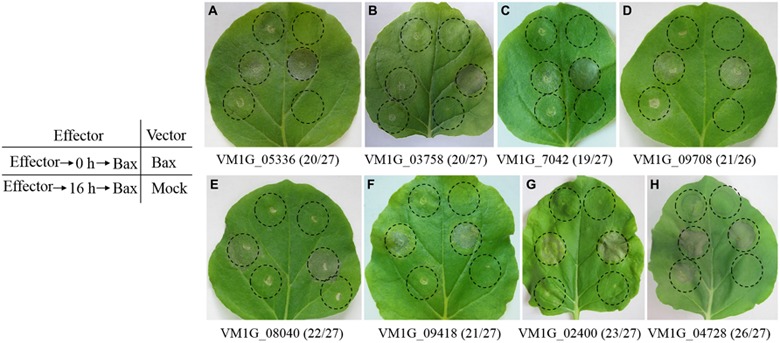

CEPs of V. mali Suppress BAX-induced PCD in N. benthamiana

Phytopathogen effectors often induce a phenotype upon over-expression in planta, reflecting their virulence activity. To investigate the function of the CEPs of V. mali, we tested the ability of CEPs to induce cell death, or to suppress BAX-induced PCD in N. benthamiana. Based on transient over-expression in N. benthamiana performed for 70 randomly selected CEPs, seven V. mali Effector Proteins (VmEPs) significantly suppressed BAX-induced PCD. Others had little or no effect on suppressing PCD (Figure 2). In addition, all 70 CEPs tested could not induce cell death in N. benthamiana. Of these 7 VmEPs, VM1G_05336 is V. mali-specific and the others are hypothetical proteins that have homologs in GenBank NR database. Intriguingly, VmEP1 (VM1G_02400) contained a HeLo domain (Table 1) that is exclusively in the fungal kingdom and is similar as other cell death and apoptosis-inducing domains (Fedorova et al., 2005).

FIGURE 2.

Symptoms of transient expression of CEPs in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves after agro-infiltration. (A–G) Seven VmEPs suppress BAX-induced cell death. (H) Most CEPs, like VM1G_04728, could not suppress BAX-induced PCD. Leaves were infiltrated with A. tumefaciens containing a PVX vector, either empty, or carrying the Bax gene, or the candidate effector genes within the regions indicated by the dashed lines. Photos were taken four to 5 days after the last infiltration. Numbers, for instance 20/27, indicate that 20 out of 27 times infiltrated leaves showed the same symptoms.

Table 1.

Sequence information of Valsa mali effector proteins (VmEPs).

| Gene_ID | Accession No. | Description | Length/AA | Cysteine content | Pfam domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VM1G_02400 | KR868746 | Hypothetical protein | 370 | 8 | HeLo (PF14479) |

| VM1G_03758 | KR868747 | Hypothetical protein | 134 | 2 | NA |

| VM1G_05336 | KR868748 | NA | 101 | 2 | NA |

| VM1G_07042 | KR868749 | Hypothetical protein | 330 | 4 | NA |

| VM1G_08040 | KR868750 | Hypothetical protein | 272 | 1 | Peroxidase 2 (PF01328) |

| VM1G_09418 | KR868751 | Hypothetical protein | 205 | 2 | NA |

| VM1G_09708 | KR868752 | Hypothetical protein | 285 | 3 | NA |

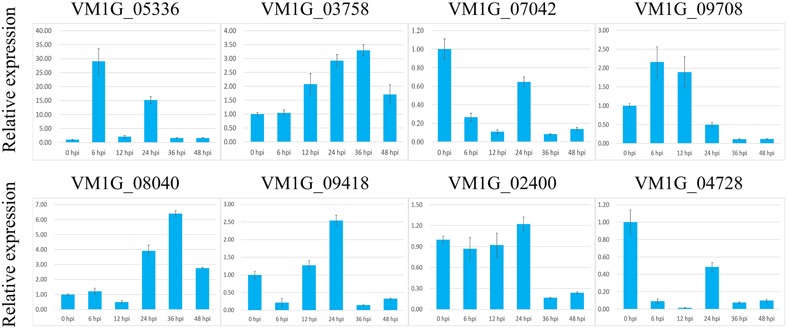

Transcription Level of V. mali Candidate Effector Genes

Fungal effector proteins are generally characterized by specific expression during invasion of plant cells. The expression levels of the 7 VmEP genes identified above were assayed by qRT-PCR with housekeeping gene G6PDH as control (Figure 3). Result showed that 5 of the 7 VmEP genes were up-regulated (fold change >2) during infection. Particularly, the V. mali-specific VM1G_05336 was remarkably induced at 6 and 24 hpi.

FIGURE 3.

Relative expression level of VmEps at 0, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours post inoculation (hpi) using reference gene G6PDH for normalization. Results are presented as a mean fold change in relative expression compared to the 0 hpi sampling stage. All experiments were repeated three times. Error bars indicate SEM.

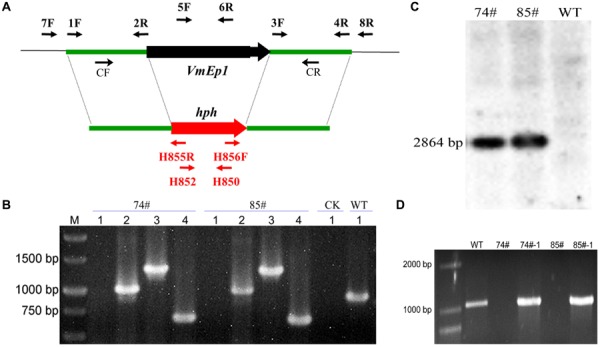

Candidate Effector VmEP1 is a Virulence Factor of V. mali

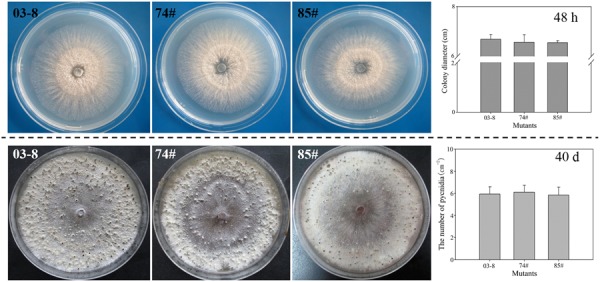

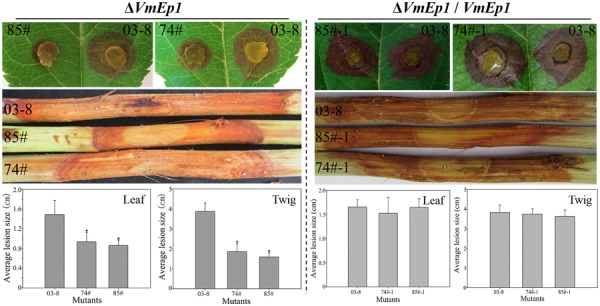

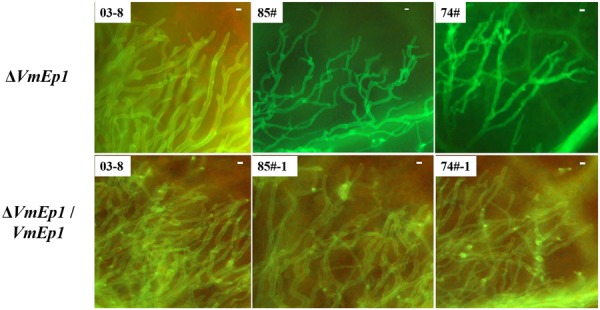

To investigate the function of VmEPs, the putative necrosis-inducing protein VmEP1 (VM1G_02400) and the V. mali-specific VM1G_05336 were chosen for further study. Gene deletion was performed using a gene replacement strategy (Figure 4A). However, only deletion mutants of VmEP1 were obtained. Among the resulting 125 hygromycin-resistant transformants of VmEP1, two were identified by PCR analysis (Figure 4B). These two VmEp1 deletion mutants (74# and 85#) were further confirmed by Southern hybridization (Figure 4C). Complementation of both mutants using a VmEp1 expressing plasmid was again confirmed by PCR using the primer pair VmEP1 5F/6R (Figure 4D). VmEp1 deletion mutants showed no effect on vegetative growth and conidiation on PDA medium (Figure 5). Intriguingly, pathogenicity assays showed that both deletion mutants had significantly reduced virulence on apple twigs and leaves (Figure 6). ΔVmEp1/VmEp1 complemented mutants 74#-1 and 85#-1 exhibit similar virulence as the wild type isolate 03–8 (Figure 6). Results from epifluorescence microscopy show that deletion mutants have reduced mycelia growth within the leaf compared to the wild type which can be rescued by introducing the complementing plasmids (Figure 7). These results indicate that VmEp1 is undoubtedly involved in virulence of V. mali.

FIGURE 4.

Generation and identification of VmEp1 deletion and complementation mutants. (A) Gene replacement strategy of VmEp1. Primer pairs 1F/2R and 3F/4R used for WT amplicon. The hygromycin-resistance cassette (hph) is denoted by the large red arrow. Primer binding sites are indicated by black arrows (see Supplementary Table S2 for primer sequences). (B) Identification of VmEp1 knockout mutants by PCR analysis. 1–4 primer pairs: (1) VmEP1-5F/6R (targeted gene), (2) VmEP1-7F/H855R upstream region), (3) VmEP1-H856F/8R (downstream region), and (4) H850/H852 (hph cassette). (C) Southern blot hybridization analysis of VmEp1 mutants using primer H850/H852. (D) Identification of VmEp1 complementation mutants by PCR analysis using primer pair VmEP1-5F/6R.

FIGURE 5.

Impact of VmEp1 deletion on vegetative growth and conidiation. Wild-type (03–8), and VmEp1 deletion mutants (74#) and (85#) were grown on PDA for 48 h or 40 days at 25°C. Colony diameter and number of mature pycnidia were counted. Bars indicate standard deviation of the mean of 30 individual dishes. The experiment was repeated three times.

FIGURE 6.

Pathogenicity of mutants. Wild-type (03–8), VmEp1 deletion mutants (74#) and (85#), and complementation mutants (74#-1) and (85#-1) were inoculated on leaves and twigs of Malus domestica borkh. cv. ‘Fuji’ for 60 h, or 5 days, respectively. Asterisk represents a significant difference in pathogenicity (P < 0.05). Bars indicate standard deviation of the mean of 30 individual host plants. The experiment was repeated three times.

FIGURE 7.

Epifluorescence microscopy of tissue colonization during infection. Boundary-zones (∼0.5 cm2) of inoculated leaves were sampled at 60 hpi. All treatments were performed with at least five replicates, and all experiments were repeated three times. Bar = 10 μm.

Discussion

In the genome of V. mali, we previously identified 193 genes encoding secreted proteins with no known function (Yin et al., 2015). In this study, we identified seven V. mali Effector Protein (VmEP) genes by a functional screen of these proteins, based on a virus in planta over-expression system. We showed that transient expression of each of these seven VmEPs significantly suppressed BAX-induced PCD in N. benthamiana, five genes of which were up-regulated during infection. While the ability to suppress BAX-triggered PCD is a valuable initial screen for pathogen effectors (Wang et al., 2011a), for it physiologically resembles defense-related HR (Lacomme and Santa Cruz, 1999), this result strongly suggests that V. mali expresses secreted proteins during plant infection, which can suppress effector-triggered plant immunity (ETI) responses in the host.

Effectors of necrotrophic pathogens interact with their host in a gene-for-gene relationship to initiate disease, which leads to ETS (Jones and Dangl, 2006; Oliver and Solomon, 2010; Wang et al., 2014). The host specific toxins secreted by Cochliobolus victoriae are translocated into plant cells to interact with specific corresponding host proteins to promote host cell death (Donofrio and Wilson, 2014; Kuhn and Panstruga, 2014). Likewise, the proteinaceous host specific toxin PtrToxA produced by P. tritici-repentis targets a host chloroplastic protein, which disrupts the photosynthetic capacity and triggers PCD (Stergiopoulos et al., 2013; Petre and Kamoun, 2014). Indeed, most of the identified effectors of necrotrophic pathogens are found to promote host cell death (Wang et al., 2014). However, because we screened these effector candidates on non-host N. benthamiana, seven out of 70 examined candidate effectors of V. mali suppress BAX-induced PCD and not a single one was found to induce PCD in N. benthamiana. Considering that many effectors of necrotrophic pathogen are host-specific toxins, it is necessary to examine ability of these CEPs to induce necrosis on hosts to determine whether they could be proteinaceous toxins.

Recently, the classic necrotrophic fungus S. sclerotiorum was found to have a biotrophic phase at the very early stage of infection (Kabbage et al., 2013). Oxalic acid secreted by this fungus can suppress host autophagy which is a defense response in its interaction with its host. Indeed, S. sclerotiorum suppresses the defense-related autophagy/PCD at an early stage of infection, and promotes disease-related apoptosis/PCD after infection established (Kabbage et al., 2013). This means that not all forms of cell deaths are equivalent. One type of cell death may be suppressed by a necrotrophic pathogen to inhibit plant defense responses, while another may be promoted to facilitate disease progress. The effectors identified in this study in V. mali probably participate in the suppression of defense-related PCD. Nevertheless, the interaction targets of these effector proteins in apple need to be determined to verify their exact roles in V. mali–apple interaction. Especially for VmEP1, because targeted deletion of VmEP1 gene results in a significant reduction in virulence.

As a necrotrophic fungus, V. mali is thought to contain virulence factors that induce cell death. Particularly, the impressive arsenal of plant cell wall degrading enzymes and secondary metabolites may account for the severe necrosis observed on apple bark (Yin et al., 2015). Deletion of six pectinase genes significantly reduced virulence of V. mali (Yin et al., 2015). Phytotoxic small polypeptides secreted by the closely related peach canker pathogens Leucostoma persoonii and L. cincta can only induce stem necrosis on host plants, reflecting a host specific characteristic (Svircev et al., 1991). In addition, V. mali also possesses homologs of necrosis-inducing factors including NPP1, Ecp2, and Epl (Yin et al., 2015). Likewise, these potential virulence factors also need to be functionally verified.

Author Contributions

ZL and ZY contributed equally to this work as first authors. LH designed and managed the project. ZL, YF, and MX performed the experimental work. ZY performed all the computational analysis. ZL, ZY, ZK, and LH wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The review editor Weixing Shan declares that, despite being affiliated with the same institution as authors Zhiyuan Yin, Xu Ming, and ZhenPeng Li, the review process was carried out objectively. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31471732, 31171796), the Program for Agriculture (nyhyzx201203034-03) and the 111 Project (B07049). Authors wish to thank Fengming Song (Zhejiang University, China) for providing the pBIG2RHPH2-GFP-GUS plasmid and Dr. Ralf T. Voegele at Universität Hohenheim for proofreading this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2015.00579

References

- Abramovitch R. B., Kim Y. J., Chen S., Dickman M. B., Martin G. B. (2003). Pseudomonas type III effector AvrPtoB induces plant disease susceptibility by inhibition of host programmed cell death. EMBO J. 22 60–69. 10.1093/emboj/cdg006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ba A. N. N., Pogoutse A., Provart N., Moses A. M. (2009). NLStradamus: a simple Hidden Markov Model for nuclear localization signal prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 10:202 10.1186/1471-2105-10-202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Boden M., Buske F. A., Frith M., Grant C. E., Clementi L., et al. (2009). MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 W202–W208. 10.1093/nar/gkp335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno K. S., Tenjo F., Li L., Hamer J. E., Xu J.-R. (2004). Cellular localization and role of kinase activity of PMK1 in Magnaporthe grisea. Eukaryot. Cell 3 1525–1532. 10.1128/EC.3.6.1525-1532.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds P. N., Rafiqi M., Gan P. H., Hardham A. R., Jones D. A., Ellis J. G. (2009). Effectors of biotrophic fungi and oomycetes: pathogenicity factors and triggers of host resistance. New Phytol. 183 993–1000. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02922.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donofrio N. M., Raman V. (2012). Roles and delivery mechanisms of fungal effectors during infection development: common threads and new directions. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15 692–698. 10.1016/j.mib.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donofrio N. M., Wilson R. A. (2014). Redox and rice blast: new tools for dissecting molecular fungal–plant interactions. New Phytol. 201 367–369. 10.1111/nph.12623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou D., Kale S. D., Wang X., Chen Y., Wang Q., Wang X., et al. (2008). Conserved C-terminal motifs required for avirulence and suppression of cell death by Phytophthora sojae effector Avr1b. Plant Cell 20 1118–1133. 10.1105/tpc.107.057067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright A. J., van Dongen S., Ouzounis C. A. (2002). An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 1575–1584. 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorova N. D., Badger J. H., Robson G. D., Wortman J. R., Nierman W. C. (2005). Comparative analysis of programmed cell death pathways in filamentous fungi. BMC Genomics 6:177 10.1186/1471-2164-6-177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Li Y., Ke X., Kang Z., Huang L. (2011). Development of genetic transformation system of Valsa mali of apple mediated by PEG. Acta Microbiol. Sin. 51 1194–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo M. C., Valent B. (2013). Filamentous plant pathogen effectors in action. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11 800–814. 10.1038/nrmicro3119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey D., Bohlenius H., Pedersen C., Zhang Z., Emmersen J., Thordal-Christensen H. (2010). Powdery mildew fungal effector candidates share N-terminal Y/F/WxC-motif. BMC Genomics 11:317 10.1186/1471-2164-11-317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood M. E., Shew H. D. (1996). Applications of KOH-aniline blue fluorescence in the study of plant-fungal interactions. Phytopathology 86 704–708. 10.1094/Phyto-86-704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. D., Dangl J. L. (2006). The plant immune system. Nature 444 323–329. 10.1038/nature05286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbage M., Williams B., Dickman M. B. (2013). Cell death control: the interplay of apoptosis and autophagy in the pathogenicity of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003287 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale S. D., Gu B., Capelluto D. G., Dou D., Feldman E., Rumore A., et al. (2010). External lipid PI3P mediates entry of eukaryotic pathogen effectors into plant and animal host cells. Cell 142 284–295. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke X., Huang L., Han Q., Gao X., Kang Z. (2013). Histological and cytological investigations of the infection and colonization of apple bark by Valsa mali var. mali. Australas. Plant Pathol. 42 85–93. 10.1007/s13313-012-0158-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ke X., Yin Z., Song N., Dai Q., Voegele R. T., Liu Y., et al. (2014). Transcriptome profiling to identify genes involved in pathogenicity of Valsa mali on apple tree. Fungal Genet. Biol. 68 31–38. 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn H., Panstruga R. (2014). Introduction to a virtual special issue on phytopathogen effector proteins. New Phytol. 202 727–730. 10.1111/nph.12804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacomme C., Santa Cruz S. (1999). Bax-induced cell death in tobacco is similar to the hypersensitive response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 7956–7961. 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. H., Lee S. W., Choi K. H., Kim D. A., Uhm J. Y. (2006). Survey on the occurrence of apple diseases in Korea from 1992 to 2000. Plant Pathol. J. 22 375–380. 10.5423/PPJ.2006.22.4.375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Gao X., Du Z., Hu Y., Kang Z., Huang L. (2013). Survey of apple Valsa canker in Weibei area of Shaanxi province. Acta Agric. Boreali Occidentalis Sin. 1 029. [Google Scholar]

- Mengiste T. (2012). Plant immunity to necrotrophs. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 50 267–294. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-172955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva R., Win J., Raffaele S., Boutemy L., Bozkurt T. O., Chaparro-Garcia A., et al. (2010). Recent developments in effector biology of filamentous plant pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 12 705–715. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver R. P., Solomon P. S. (2010). New developments in pathogenicity and virulence of necrotrophs. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13 415–419. 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petre B., Kamoun S. (2014). How do filamentous pathogens deliver effector proteins into plant cells? PLoS Biol. 12:e1001801 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout C. J., Skamnioti P., Porritt O., Sacristan S., Jones J. D., Brown J. K. (2006). Multiple avirulence paralogues in cereal powdery mildew fungi may contribute to parasite fitness and defeat of plant resistance. Plant Cell 18 2402–2414. 10.1105/tpc.106.043307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders D. G., Win J., Cano L. M., Szabo L. J., Kamoun S., Raffaele S. (2012). Using hierarchical clustering of secreted protein families to classify and rank candidate effectors of rust fungi. PLoS ONE 7:e29847 10.1371/journal.pone.0029847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stergiopoulos I., Collemare J., Mehrabi R., de Wit P. J. (2013). Phytotoxic secondary metabolites and peptides produced by plant pathogenic Dothideomycete fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37 67–93. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00349.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svircev A., Biggs A., Miles N. (1991). Isolation and partial purification of phytotoxins from liquid cultures of Leucostoma cincta and Leucostoma persoonii. Can. J. Bot. 69 1998–2003. 10.1139/b91-251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vleeshouwers V. G., Oliver R. P. (2014). Effectors as tools in disease resistance breeding against biotrophic, hemibiotrophic, and necrotrophic plant pathogens. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 27 196–206. 10.1094/MPMI-10-13-0313-IA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Han C., Ferreira A. O., Yu X., Ye W., Tripathy S., et al. (2011a). Transcriptional programming and functional interactions within the Phytophthora sojae RXLR effector repertoire. Plant Cell 23 2064–2086. 10.1105/tpc.111.086082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Wei J., Huang L., Kang Z. (2011b). Re-evaluation of pathogens causing Valsa canker on apple in China. Mycologia 103 317–324. 10.3852/09-165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Jiang N., Liu J., Liu W., Wang G. L. (2014). The role of effectors and host immunity in plant–necrotrophic fungal interactions. Virulence 5 722–732. 10.4161/viru.29798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z., Ke X., Huang D., Gao X., Voegele R. T., Kang Z., et al. (2013). Validation of reference genes for gene expression analysis in Valsa mali var. mali using real-time quantitative PCR. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 29 1563–1571. 10.1007/s11274-013-1320-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z., Liu H., Li Z., Ke X., Dou D., Gao X., et al. (2015). Genome sequence of Valsa canker pathogens uncovers a potential adaptation of colonization of woody bark. New Phytol. 10.1111/nph.13544 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., Hamari Z., Han K., Seo J., Reyes-Domínguez Y., Scazzocchio C. (2004). Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulations in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43 973–981. 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Zhang H., Li G., Shaw B., Xu J. R. (2012). The cyclase-associated protein Cap1 is important for proper regulation of infection-related morphogenesis in Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002911 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Zhang M., Zhai L., Yang X., Cao S., Hong N., et al. (2014). Comparison of pathogenicity of Valsa mali strains showing different culturing phenotypes. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 44 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Wei W., Fu Y., Cheng J., Xie J., Li G., et al. (2013). A secretory protein of necrotrophic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum that suppresses host resistance. PloS ONE 8:e53901 10.1371/journal.pone.0053901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.