Abstract

Background

Authors’ conflicts of interest may affect the content of medical guidelines. In April 2010, the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF) issued recommendations on how such conflicts of interest should be dealt with. Most AWMF guidelines are so-called S1 guidelines developed by informal consensus in a group of experts. We now present the first study to date on the management of conflicts of interest in S1 guidelines.

Methods

On 2 December 2013, we selected the guidelines that had appeared from 1 November 2010 to 1 November 2013 among the 449 current S1 guidelines on the AWMF website. We extracted information about conflicts of interest from the guideline texts, reports, and/or conflict of interest statements and evaluated this information descriptively.

Results

There were 234 S1 guidelines in this category, developed by a total of 2190 experts. For 7% (16/234) of the guidelines and 16% (354/2190) of the experts, no individual conflict of interest statement could be found. Where conflict of interest statements were available, conflicts of interest were often declared—in 98% (213/218) of the guidelines and by 85% (1565/1836) of the authors. The most common type of conflict of interest was membership in a specialist society or professional association (1571/1836, 86%). Half of the experts acknowledged a financial conflict of interest (911/1836, 50%). Conflicts of interest were more common among experts contributing to guidelines that mainly concerned treatment with drugs or other medical products than in guidelines that did not have an emphasis of this type (397/663, or 60%, versus 528/1173, or 45%). The conflicts of interest were assessed in 11% (25/234) of the guidelines, with practical consequences in a single case.

Conclusion

Conflicts of interest are often declared in the S1 guidelines of the AWMF, but they are only rarely assessed by external evaluators. Clear rules should be issued for how experts’ declared conflicts of interest should be acted upon, whether they are of a financial nature or not.

Clinical guidelines are developed in order to support physicians and patients in specific clinical situations when decisions concerning diagnosis and treatment are made. Recommendations provided in guidelines are based on the findings of clinical studies and on expert opinion. Identical study findings may be evaluated differently depending on whether or not guideline authors have conflicts of interest (1).

A conflict of interest is defined as a circumstance that gives rise to a risk that professional judgement or actions concerning a primary interest may be inappropriately influenced by a secondary interest (2, 3). A conflict of interest is therefore a state of affairs, not a biased evaluation or the result of a particular act (3, 4). The primary interest is in line with an individual’s professional activities, in the case of doctors the best possible patient care. Secondary interests may be financial, psychological, or social in nature (5). An example of a financial secondary interest is a financial link with manufacturers of drugs or medical devices—accepting gifts or fees for consultancy or lectures, for instance. However, no system for remunerating physicians’ work can help but create secondary interests, and these inevitably conflict with primary interests. Nonfinancial interests may be, for example, the adoption of a particular treatment-related conviction or school of thought. Nonfinancial conflicts of interest often go hand in hand with financial ones (3, 5).

Studies conducted in various countries show that many guidelines (36 to 98%) contain no information on conflicts of interest. When conflict of interest statements are made, multiple conflicts of interest are often declared (6– 17).

In Germany, the Association of Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften) coordinates specialist societies’ development of guidelines on diagnosis and treatment. Member societies’ guidelines are divided into three tiers according to how they are developed:

S1 guidelines are developed by a group of experts who come to an informal consensus.

S2 guidelines are based on either the structured consensus of a representative committee or a systematic analysis of the scientific evidence.

S3 guidelines meet both the criteria above (18).

The AWMF has developed recommendations on handling conflicts of interest, which it published in April 2010 (19). These are based on recommendations made by the US Institute of Medicine (IoM) which have also been discussed and adapted in Germany (2, 20, 21). The AWMF’s regulations include, among others, the following:

Conflicts of interest must be declared and published using a form.

Authors’ declarations must be evaluated by the steering committee and the guideline coordinators.

Collaborators assessed as being biased must be excluded from the evaluation of evidence and development of consensus.

Care should be taken that authors are free of significant conflicts of interest.

Guidelines in which conflicts of interest of individual collaborators are not transparent must not be included in the AWMF register.

The AWMF provides a template form for download on its homepage for conflict of interest statements (22). This contains nine points that inquire into financial and nonfinancial conflicts of interest in the last three years.

There are two studies available in Germany concerning the handling of conflicts of interest when guidelines are compiled. An analysis of dermatology guidelines dating from 2010 shows that information on guideline funding and authors’ conflicts of interest is insufficient (14). A study of S2 and S3 guidelines of German specialist societies dating from 2009 to 2011 shows, in particular, significant shortcomings in handling conflicts of interest: although the practice of disclosing conflicts of interest has become established, the duty to disclose them does not lead to discernible countermeasures (10).

However, the majority of all AWMF guidelines, approximately 60%, are S1 guidelines (23). These provide recommendations which may sometimes even have legal consequences if breached (24). S1 guidelines are developed as a result of informal consensus reached by a group of experts. This makes it particularly important that authors’ conflicts of interest be handled transparently. Because there are no studies as yet on conflicts of interest among authors of S1 guidelines, this study addressed the following questions:

How frequently are conflicts of interest declared in S1 guidelines, and what information about them is provided?

Are authors of guidelines on the use of drugs more likely to have financial conflicts of interest than those of guidelines on other subjects?

Do any consequences result from declared conflicts of interest?

Are the AWMF’s April 2010 recommendations on handling conflicts of interest implemented?

Methods

On 2 December 2013 there were a total of 449 current S1 guidelines on the AWMF homepage (23). This study investigated guidelines that had been finalized at least six months after the publication of the AWMF’s recommendations in April 2010: S1 guidelines dated 1 November 2010 to 1 November 2013. Guideline texts, guideline reports, and conflict of interest statements were searched for information on conflicts of interest, and this information was downloaded.

For every text, several investigators (Henry Pachl, Stephan Schmutz, and Gisela Schott) ascertained how many people were listed as authors and whether any conflicts of interest were stated. Where necessary, consensus was reached between these investigators after consulting the documents in question again. When conflicts of interest were stated (e.g. in the AWMF form), the information was evaluated. The AWMF form contains questions on the following points, among others (22):

Acting as a consultant or expert in a health care company

Lecture or training fees

Financing (third-party funds) for research, staff funding

Ownership interests in drugs/medical devices

Possession of company stock or shares

Personal relationships with a company’s authorized representative

Membership in specialist societies/professional associations

Academic or personal interests

Employer(s) within the last three years.

The point referring to employers was not included in the evaluation.

The guidelines were divided into four categories in line with criterion 23 (“Conflicts of interest of members of the panel that developed the guideline were documented”) of the German Guideline Appraisal Instrument (DELBI, Deutsches Leitlinien-Bewertungsinstrument) (25). These categories were as follows:

The guideline provides no information on conflicts of interest.

The guideline contains a global conflict of interest statement.

The guideline contains a form that inquires into the conflicts of interest of individual authors.

The guideline contains an evaluation of conflicts of interest or information on their consequences.

The guidelines were also divided into those on the use of drugs and those on other subjects. The distinguishing criterion was for at least one drug to be named and its dosage stated in the guideline (background text or recommendation).

The empirical data obtained in this way was processed using descriptive statistical methods and represented in tables and figures. Guidelines on the use of drugs and those on other subjects were compared using a mixed logistic model with generalized estimating equations. This takes into account authors’ affiliation with the guideline in question.

Results

A total of 234 S1 guidelines of 34 responsible specialist societies were investigated. Altogether, 2190 experts were involved in guideline development as authors or members of groups of experts. Some of these were involved in more than one guideline.

Information on conflicts of interest

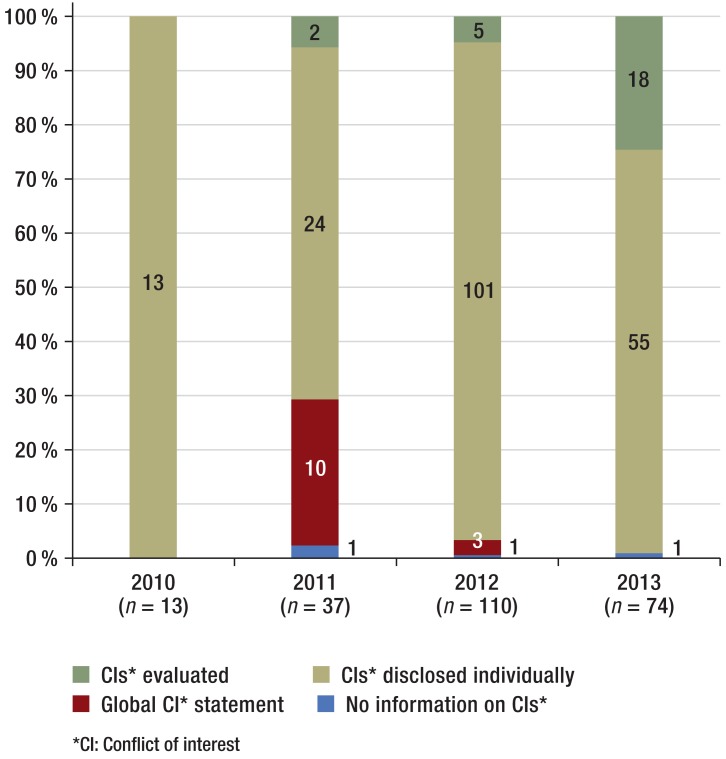

In the majority of guidelines (218/234, 93%) conflict of interest statements were provided as forms completed individually by the authors (Table 1a), while in 7% there was either no conflict of interest statement or only a global one (3/234 and 13/234 respectively). Information evaluating conflicts of interest was provided for 25 guidelines (25/234, 11%). During the study period there was a trend towards fewer global conflict of interest statements, and more evaluations of conflicts of interest, over time (Figure 1).

Table 1a. Information on conflicts of interest in S1 guidelines.

| Guidelines: n = 234* | Proportion | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Individual conflict of interest statement available | 218/234 | 93% |

| Evaluation of conflicts of interest available | 25/234 | 11% |

| Conflicts of interest led to consequence | 1/234 | 0.4% |

| Guidelines for which an individual conflict of interest statement is available, n = 218 | ||

| Guidelines by authors with no conflicts of interest | 5/218 | 2% |

| Guidelines by authors with nonfinancial conflicts of interest only | 27/218 | 12% |

| Guidelines by authors with one or more financial conflict of interest | 186/218 | 85% |

*One guideline listed no authors and was excluded from these figures

Figure 1.

Information on conflicts of interest provided in S1 guidelines (n = 234) during the study period

For most authors (1836/2190, 84%), conflict of interest statements were fully visible (Table 1b). The percentage of authors per year with no or incomplete conflict of interest statements was between 6 and 19%, with no clear trend over the study period (2010: 9/148 authors, 6%; 2011: 72/300 authors, 24%; 2012: 203/1086 authors, 19%; 2013: 70/656 authors, 11%).

Table 1b. Information on conflicts of interest in S1 guidelines.

| Authors: n = 2190 | Proportion | Percentage (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Individual conflict of interest statement available | 1836/2190 | 84% (81 to 87) |

| Evaluation of conflicts of interest available | 111/2190 | 5% (3.0 to 8.5) |

| Conflicts of interest led to consequence | 1/2190 | 0.05% |

| Authors for whom an individual conflict of interest statement is available, n = 1836 | ||

| Authors with no conflicts of interest | 271/1836 | 15% (12 to 18) |

| Authors with nonfinancial conflicts of interest only | 640/1836 | 35% (31 to 38) |

| Authors with one or more financial conflict of interest (AWMF questions 1 to 5) | 925/1836 | 50% (46 to 55) |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; AWMF, Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften)

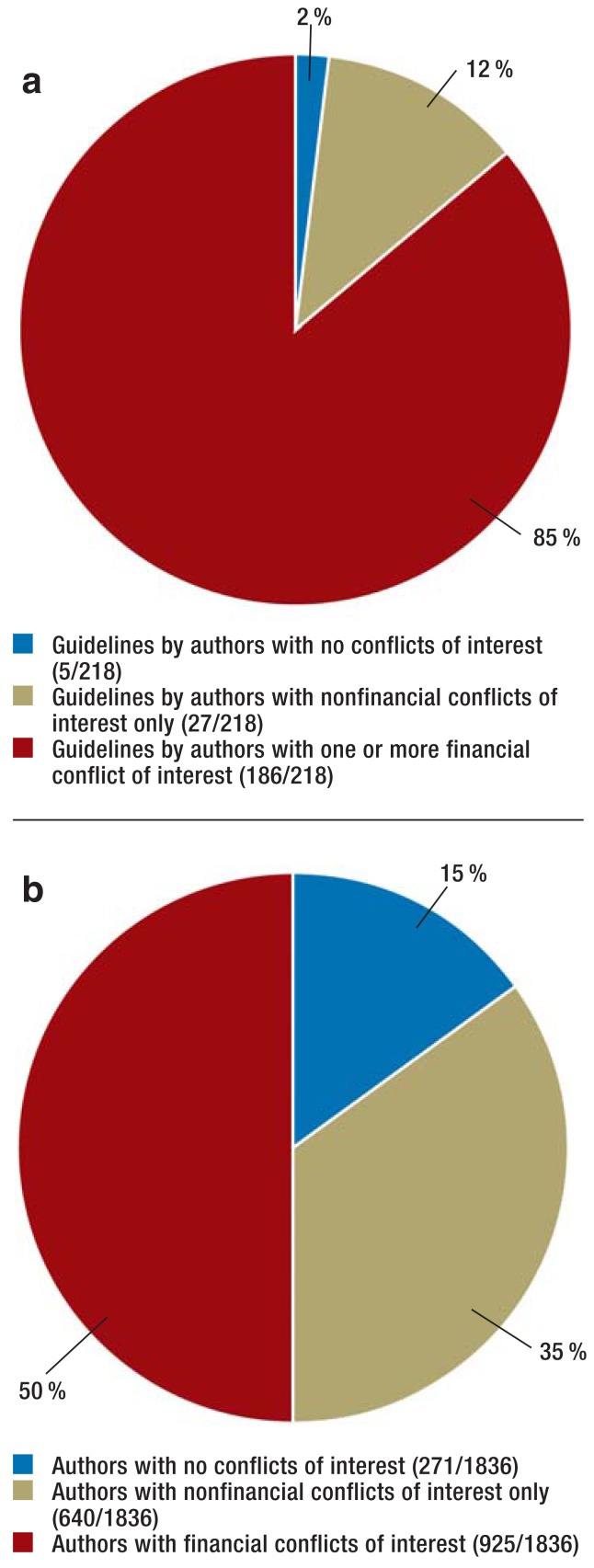

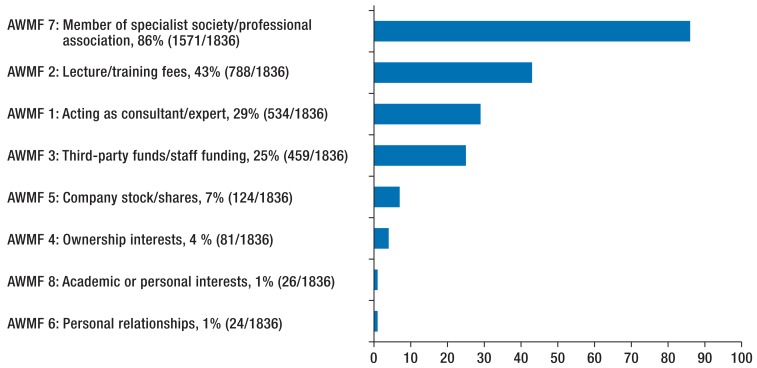

Where conflict of interest statements were available, conflicts of interest were often declared: this was the case in 98% of guidelines (213/218) and for 85% of authors (1565/1836) (Figure 2). The most common conflicts of interest were membership in specialist societies and professional associations and acting as a representative (question 7 of the AWMF form, 1571/1836, 86%) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

a) guidelines (n = 218) and

b) authors (n = 1836) where conflict of interest statements were provided

Figure 3.

Type of conflict of interest (experts with disclosed conflicts of interest, n = 1836).

“AWMF 1 to 8” refers to questions in the AWMF’s form for disclosing conflicts of interest (22)

Half of authors disclosed financial conflicts of interest (questions 1 to 5 of the AWMF form, 925/1836, 50%). Acting as a consultant or expert, or paid membership of a scientific advisory board of a health care company, was disclosed by 29% of authors (534/1836). The following were also reported: lecture fees, third-party funds for research, ownership interests in drugs/medical devices, and ownership of company stock (Figure 3). Three or more financial conflicts of interest were disclosed by 285 authors (285/1836, 16%).

Approximately one quarter of the 218 guidelines for which detailed conflict of interest statements were available were compiled by authors with no financial conflicts of interest (27/218, 12%) or in which 25% or fewer of the authors had financial conflicts of interest (28/218, 13%) (Table 2). Roughly speaking, for one additional quarter of the guidelines 26 to 50% of the authors had a financial conflict of interest (60/218, 28%), for another quarter 51 to 75% of the authors had a financial conflict of interest (43/218, 20%), and for a further quarter 76 to 100% of the authors had a financial conflict of interest (55/208 218, 25%).

Table 2. Proportion of authors with financial conflicts of interest in S1 guidelines dating from 2010 to 2013 with disclosed conflicts of interest (n = 218).

| Proportion (percentage) | |

|---|---|

| Guidelines in which 0% of authors disclosed a financial conflict of interest | 27 (12) |

| Guidelines in which 1 to 25% of authors disclosed a financial conflict of interest | 28 (13) |

| Guidelines in which 26 to 50% of authors disclosed a financial conflict of interest | 60 (28) |

| Guidelines in which 51 to 75% of authors disclosed a financial conflict of interest | 43 (20) |

| Guidelines in which 76 to 100% of authors disclosed a financial conflict of interest | 55 (25) |

| Guidelines in which the percentage of authors with a financial conflict of interest could not be determined with certainty because all authors’ conflict of interest statements were incomplete or absent | 5 (2) |

A substantially higher percentage of authors of guidelines on the use of drugs had financial conflicts of interest than authors of guidelines on other subjects (397/663, 60% versus 528/1173, 45%). The difference was statistically significant (odds ratio: 1.82; 95% confidence interval: 1.21 to 2.75) (Table 3).

Table 3. Financial conflicts of interest among authors of guidelines on the use of drugs and on other subjects.

| Authors with no financial conflicts of interest (AWMF form, questions 1 to 5) n = 911 |

Authors with one or more financial conflict of interest (AWMF form, questions 1 to 5) n = 925 |

Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guidelines on the use of drugs (n = 92; authors: n = 663) | 266 (40%) | 397 (60%) | 1.82 (1.21 to 2.75) |

| Guidelines on other subjects (n = 121; authors: n = 1173) | 645 (55%) | 528 (45%) |

AWMF, Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften)

Evaluation and consequences of conflicts of interest

Of the guidelines investigated, 25 contained information evaluating conflicts of interest (25/234, 11%). In five guidelines the authors performed a self-evaluation of their conflicts of interest, and in a further five conflicts of interest were evaluated by lead or coordinating authors. In 15 specialist society guidelines, a standardized sentence stated that “following evaluation by a committee (…) no conflicts of interest were identified.”

With one exception, all evaluations given came to the conclusion that there were no conflicts of interest or that the declared conflicts of interest had no significance for the guidelines.

Only one author, who had assessed his conflict of interest statement himself, believed that he had a conflict of interest. He stated that as a consequence he had abstained from voting on evaluation of the treatments on which he had been the lead author in a publication.

Discussion

Transparent handling of authors’ conflicts of interest when guidelines are developed should be part of independent evaluation of drugs or of diagnosis and treatment strategies. To this end, the AWMF published new regulations in April 2010 (19). Although implementation of these is improving, it remains inadequate, as shown in this study of 234 S1 guidelines published between November 2010 and November 2013.

Information on conflicts of interest in S1 guidelines

Even though the regulations on disclosing conflicts of interest were broadly followed, conflict of interest statements were not visible for all guidelines or all authors. Where there were statements, conflicts of interest were frequently declared: only five guidelines stated that the authors had no conflicts of interest.

The most common conflicts of interest disclosed were membership in professional associations and specialist societies. The involvement of representatives of professional associations and specialist societies in guideline compilation is essentially a sensible practice. However, it does carry the risk of biased evaluation, for example if recommendations for a particular specialist physicians’ group are advantageous. Because this affects experts’ secondary financial interests and nonfinancial interests, there are conflicts of interest. As with their financial counterparts, if nonfinancial conflicts of interest are ignored the independence of a guideline may be called into question. If individuals with specialist knowledge are excluded, guideline compilation may miss out on expertise. In order to prevent this, regulations have also been proposed for handling nonfinancial conflicts of interest (26): like financial conflicts of interest, they should be declared and evaluated. There are various possible consequences of conflicts of interest, depending on their type and extent. These range from unlimited collaboration through exclusion from voting on individual issues to exclusion from the entire project.

Half of guideline authors reported financial conflicts of interest, often including consultancy for a pharmaceutical company. In the future, the scale of financial sums received should also be recorded and disclosed, as planned by the Drug Commission of the German Medical Association (27).

In addition, financial conflicts of interest should be either taken into account or prevented as early as the expert recruitment stage. The large number of experts with no financial conflicts of interest indicates that the latter solution is possible. If collaboration with an expert with financial conflicts of interest is unavoidable, the expert should take on only an advisory role and should be excluded from voting. Data should be evaluated by individuals with no conflicts of interest.

Guidelines on the use of drugs had a substantially higher percentage of authors with financial conflicts of interest than guidelines on other subjects. This illustrates the close connections between physicians, pharmaceutical companies, and guideline committees. As a result there is a risk that pharmaceutical companies indirectly influence guidelines through financial connections with authors. This is the conclusion suggested by studies showing that guidelines involving experts with financial links to pharmaceutical companies are more likely to be in line with pharmaceutical companies’ interests than guidelines by authors without such conflicts of interest (28– 31).

The findings of this study of S1 guidelines are similar to those of a comparable analysis of S2 and S3 guidelines performed by the AWMF (10): most conflicts of interest are declared, but they are only rarely evaluated by a steering committee, and no consequences result. However, it is precisely consequences that are important. The reason for this may be that the regulations on evaluating and handling conflicts of interest have not yet been clearly, bindingly formulated. For example, the AWMF’s 2010 recommendations stated that a scale would be developed to assess the extent of conflicts of interest, but as yet there is no such scale on the AWMF website. The concept of trivial conflicts of interest also remains undefined. There is only one, nonbinding recommendation on handling members of guideline development panels who have been assessed as having a conflict of interest: they should not be involved in the evaluation of evidence or in the reaching of a consensus.

Limitations

This study did not include verification of the validity of the conflict of interest statements, as the necessary investigations could not be carried out as part of this research. For the same reason, the effects of how conflicts of interest are handled on guideline content and implementation were not analyzed. Various studies have shown that conflict of interest disclosure can have negative as well as positive effects, for example when attempts are made to compensate for such disclosure with an even stronger bias or when readers’ trust is lost (32– 36).

Conclusion

The declaration and disclosure of conflicts of interest are not sufficient to ensure that drugs and clinical strategies are evaluated as independently as possible when guidelines are compiled. It is equally important that conflicts of interest be evaluated according to a clear evaluation procedure by an independent committee. However, it is especially important for conflicts of interest to lead to consequences after they have been evaluated. Problematic conflicts of interest require effective countermeasures such as the exclusion of experts from voting on specific issues or from guideline compilation as a whole.

Key Messages.

Most AWMF S1 guidelines contain conflict of interest statements.

Where statements are available, conflicts of interest are often disclosed: membership in a professional association for 86% of authors, and a financial conflict of interest for 50% of authors.

Authors with financial conflicts of interest were more likely to be involved in guidelines on the use of drugs than guidelines on other subjects.

Conflicts of interest were only rarely evaluated by third parties, and there was only one case of a conflict of interest leading to any consequence.

The handling of financial and nonfinancial conflicts of interest should be clearly regulated and documented.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Shimakawa-Devitt, M.A.

This article is partly based on a Master’s Degree thesis by S. Schmutz (37). Interim findings were published as a meeting abstract and poster at the 14th annual conference of the German Network for Evidence-based Medicine (Deutsches Netzwerk Evidenzbasierte Medizin e. V.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Wang AT, McCoy CP, Murad MH, Montori VM. Association between industry affiliation and position on cardiovascular risk with rosiglitazone: cross sectional systematic review. BMJ. 2010;340 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice, Institute of Medicine. Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice. In: Lo B, Field MJ, editors. 1th edition. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieb K, Klemperer D, Ludwig WD. Einleitung. In: Lieb K, Klemperer D, Ludwig WD, editors. Interessenskonflikte in der Medizin - Hintergründe und Lösungsmöglichkeiten. Berlin Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2011. pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson DF. Understanding financial conflicts of interest. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:573–576. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308193290812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klemperer D. Was ist ein Interessenkonflikt und wie stellt man ihn fest? In: ieb K, Klemperer D, Ludwig W-D, editors. Interessenskonflikte in der Medizin - Hintergründe und Lösungsmöglichkeiten. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2011. pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchan HA, Currie KC, Lourey EJ, Duggan GR. Australian clinical practice guidelines—a national study. Med J Aust. 2010;192:490–494. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choudhry NK, Stelfox HT, Detsky AS. Relationships between authors of clinical practice guidelines and the pharmaceutical industry. JAMA. 2002;287:612–617. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cosgrove L, Bursztajn HJ, Krimsky S, Anaya M, Walker J. Conflicts of interest and disclosure in the American Psychiatric Association’s clinical practice guidelines. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:228–232. doi: 10.1159/000214444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kung J, Miller RR, Mackowiak PA. Failure of clinical practice guidelines to meet Institute of Medicine standards: two more decades of little, if any, progress. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1628–1633. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langer T, Conrad S, Fishman L, et al. Conflicts of interest among authors of medical guidelines: an analysis of guidelines produced by German specialist societies. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:836–842. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendelson TB, Meltzer M, Campbell EG, Caplan AL, Kirkpatrick JN. Conflicts of interest in cardiovascular clinical practice guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:577–584. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuman J, Korenstein D, Ross JS, Keyhani S. Prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among panel members producing clinical practice guidelines in Canada and United States: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papanikolaou GN, Baltogianni MS, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Haidich AB, Giannakakis IA, Ioannidis JP. Reporting of conflicts of interest in guidelines of preventive and therapeutic interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2001;1 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosumeck S, Sporbeck B, Rzany B, Nast A. Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest in dermatological guidelines in Germany—an analysis-status quo and quo vadis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor R, Giles J. Cash interests taint drug advice. Nature. 2005;437:1070–1071. doi: 10.1038/4371070a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norris SL, Holmer HK, Ogden LA, Selph SS, Fu R. Conflict of interest disclosures for clinical practice guidelines in the national guideline clearinghouse. PLoS ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bindslev JB, Schroll J, Gotzsche PC, Lundh A. Underreporting of conflicts of interest in clinical practice guidelines: cross sectional study. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14 doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-14-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopp I. Erstellung und Handhabung von Leitlinien aus Sicht der AWMF. MKG-Chirurg. 2010;2:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e. V. (AWMF) Empfehlungen der AWMF zum Umgang mit Interessenkonflikten bei Fachgesellschaften. www.awmf.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Leitlinien/Werkzeuge/empf-coi.pdf. Stand: 23. April 2010 (last accessed on 30 September 2014)

- 20.Stretch D, Klemperer D, Knüppel H, Kopp I, Meyer G, Koch K. Ein Diskussionspapier. Berlin: Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin; 2011. Deutsches Netzwerk evidenzbasierte Medizin e V. (DNEbM) (ed.): Interessenkonfliktregulierung: Internationale Entwicklungen und offene Fragen. www.ebm-netzwerk.de/was-wir-tun/pdf/interessenkonfliktregulierung-2011.pdf (last accessed 30 September 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft. Regeln zum Umgang mit Interessenkonflikten bei Mitgliedern der Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaf. www.akdae.de/Kommission/Organisation/Statuten/Interessenkonflikte/Regeln.pdf. Stand: 3. März 2014. (last accessed 30 September 2014)

- 22.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e.V. AWMF-Formular zur Erklärung von Interessenkonflikten im Rahmen von Leitlinienvorhaben. www.awmf.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Leitlinien/Werkzeuge/Formular_Interessenkonflikterklaerung.rtf. Stand: 8. Februar 2010. (last accessed 30 September 2014)

- 23.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e.V. AWMF online - das Portal der wissenschaftlichen Medizin. www.awmf.org. (last accessed 30 September 2014)

- 24.Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin (ÄZQ) Kompendium Q-M-A: Glossar. www.aezq.de/aezq/kompendium_q-m-a/15-glossar. (last accessed 11 September 2014)

- 25.Deutsches Leitlinien-Bewertungsinstrument DELBI. www.leitlinien.de/leitlinienmethodik/leitlinienbewertung/delbi. Stand: Februar 2011. (last accessed 30 December 2014)

- 26.Viswanathan M, Carey TS, Belinson SE, et al. www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/467/1514/conflict-of-interest-methods.pdf AHRQ Publication No13-EHC085-EF". Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. Identifying and managing nonfinancial conflicts of interest for systematic reviews. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osterloh F. Im Zeichen der Transparenz. Dtsch Arztebl. 2014;111 [Google Scholar]

- 28.George JN, Vesely SK, Woolf SH. Conflicts of interest and clinical recommendations: Comparison of two concurrent clinical practice guidelines for primary immune thrombocytopenia developed by different methods. Am J Med Qual. 2013;29:53–60. doi: 10.1177/1062860613481618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schott G, Dunnweber C, Muhlbauer B, Niebling W, Pachl H, Ludwig WD. Does the pharmaceutical industry influence guidelines? Two examples from Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:575–583. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenzer J. Why we can’t trust clinical guidelines. BMJ. 2013;346 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iannone P, Haupt E, Flego G, Truglio P, Minardi M, Clarke S. liability of clinical practice guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:625–629. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.PLoS Medicine Editors. Does conflict of interest disclosure worsen bias? PLoS Med. 2012;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaudhry S, Schroter S, Smith R, Morris J. Does declaration of competing interests affect readers’ perceptions? A randomised trial. BMJ. 2002;325:1391–1392. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7377.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cain DM, Loewenstein G, Moore DA. The dirt on coming clean: perverse effects of disclosing conflicts of interest. J Legal Studies. 2005;34:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kesselheim AS, Robertson CT, Myers JA, et al. A randomized study of how physicians interpret research funding disclosures. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1119–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siwek J. AFP’s conflict of interest policy: disclosure is not enough. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmutz S. Masterarbeit, vorgelegt am 31. Mai 2013. Berlin: School of Public Health an der Charité; 2013. Angaben zu Interessenkonflikten in Leitlinien der AWMF. [Google Scholar]