Abstract

AIM: To investigate the association of PNPLA3 polymorphisms with concurrent chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

METHODS: A cohort of Han patients with biopsy-proven CHB, with or without NAFLD (CHB group, n = 51; CHB + NAFLD group, n = 57), and normal controls (normal group, n = 47) were recruited from Northern (Tianjin), Central (Shanghai), and Southern (Zhangzhou) China. Their PNPLA3 polymorphisms were genotyped by gene sequencing. The association between PNPLA3 polymorphisms and susceptibility to NAFLD, and clinical characteristics of NAFLD were evaluated on the basis of physical indices, liver function tests, glycolipid metabolism, and histopathologic scoring. The association of PNPLA3 polymorphisms and hepatitis B virus (HBV) load was determined by the serum level of HBV DNA.

RESULTS: After adjusting for age, sex, and body mass index, we found that four linked single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of PNPLA3, including the rs738409 G allele (CHB + NAFLD group vs CHB group: odds ratio [OR] = 2.77, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.18-6.54; P = 0.02), rs3747206 T allele (CHB + NAFLD group vs CHB group: OR = 2.77, 95%CI: 1.18-6.54; P = 0.02), rs4823173 A allele (CHB + NAFLD group vs CHB group: OR = 2.73, 95%CI: 1.16-6.44; P = 0.02), and rs2072906 G allele (CHB + NAFLD group vs CHB group: OR = 3.05, 95%CI: 1.28-7.26; P = 0.01), conferred high risk to NAFLD in CHB patients. In patients with both CHB and NAFLD, these genotypes of PNPLA3 polymorphisms were associated with increased susceptibility to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (NAFLD activity score ≥ 3; P = 0.01-0.03) and liver fibrosis (> 1 Metavir grading; P = 0.01-0.04). As compared to those with C/C and C/G at rs738409, C/C and C/T at rs3747206, G/G and G/A at rs4823173, and A/A and A/G at rs2072906, patients in the CHB + NAFLD group with G/G at rs738409, T/T at rs3747206, A/A at rs4823173, and G/G at rs2072906 showed significantly lower serum levels of HBV DNA (P < 0.01-0.05).

CONCLUSION: Four linked SNPs of PNPLA3 (rs738409, rs3747206, rs4823173, and rs2072906) are correlated with susceptibility to NAFLD, NASH, liver fibrosis, and HBV dynamics in CHB patients.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis B, Hepatitis B virus, Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, PNPLA3, Single-nucleotide polymorphism

Core tip: The association of PNPLA3 polymorphisms with concurrent chronic hepatitis B and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease was determined in Chinese Han patients. The effect of PNPLA3 genotypes on hepatitis B virus load was also evaluated. Four linked single-nucleotide polymorphisms of PNPLA3 (rs738409 G allele, rs3747206 T allele, rs4823173 A allele, and rs2072906 G allele) conferred susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients. Patients carrying these single-nucleotide polymorphisms showed a significantly lower serum level of hepatitis B virus DNA.

INTRODUCTION

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an acquired, metabolic, stress-induced liver disease associated with insulin resistance and genetic susceptibility[1]. A “two-hit hypothesis” has been proposed to describe the pathologic progression of NAFLD, in which a high-fat diet causes hepatic fat accumulation as the first hit, and oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, cytokines, adipokines, bacterial endotoxins, and endoplasmic reticulum stress cause the second hit[2]. The clinical spectrum of NAFLD ranges from simple steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), but can progress to liver cirrhosis and finally hepatocellular carcinoma[3].

Adiponutrin, encoded by PNPLA3 on chromosome 22q13, has both triacylglycerol hydrolase and acylglycerol transacetylase activity in hepatocytes. A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in PNPLA3 (rs738409 C>G), which results in an adiponutrin variant with I148M (isoleucine-to-methionine substitution at residue 148), has been identified as a predisposing factor for liver steatosis. The adiponutrin variant is linked to reduced triglyceride hydrolysis in hepatocytes[4,5]. Moreover, the PNPLA3 rs738409 G allele is closely associated with NASH[6], hepatic fibrosis/cirrhosis[4,7] and hepatocellular carcinoma[8], regardless of the degree of obesity[9]. Except for rs738409, PNPLA3 rs2281135 was recently reported to be in tight linkage disequilibrium (LD) in four human ethnic groups (African, Caucasian, East Asian, and Mexican Americans) with NAFLD[10]. PNPLA3 rs139051 TT is also associated with increased risk of NAFLD in the Chinese Han population[11]. Similar results were reported in a previous study, which showed that PNPLA3 rs2294918 was associated with NASH in European and American populations[12]. Some other PNPLA3 polymorphisms, including rs2281135 and rs6006460, influence serum alanine aminotransferase activity[12] and hepatic fat content[13], respectively. Polymorphism of PNPLA3, therefore, seems to serve as the genetic basis for histologic progression of NAFLD.

With the increasing prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome, NAFLD has now become a commonly occurring liver disease and a public health burden in most areas of China[3]. In Western countries, high-fat diet-induced NAFLD occurs in the absence of hepatitis-virus-induced liver disease. However, the high prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in the Chinese population causes concurrent NAFLD and chronic hepatitis B (CHB) in China[14,15]. Of the studies published to date, hepatic steatosis occurs at rates of 60% (213 cases), 51.2% (86 cases), 13.5% (91 cases), and 14% (1915 cases) in patients from Greece[16], South Korea[17], Hong Kong (China)[18], and Hang Zhou (China)[19], respectively.

Recent experimental evidence indicates that PNPLA3 polymorphisms may play a role in the concurrent development of NAFLD and chronic viral hepatitis. In patients infected with genotype 2 hepatitis C virus (HCV), the PNPLA3 I148M variant correlates with significantly increased insulin resistance. In PNPLA3 I148M carriers, the viral load is significantly lower at baseline and after 3-7 d of antiviral treatment[20]. However, the role of the PNPLA3 polymorphism in patients with NAFLD and CHB has not yet been established.

Therefore, we characterized SNPs of PNPLA3 in Han patients with biopsy-proven CHB with or without NAFLD from Northern (Tianjin), Central (Shanghai), and Southern (Zhangzhou) China. The association of PNPLA3 polymorphisms with clinical, laboratory, and pathologic characteristics of NAFLD was evaluated. The correlation between PNPLA3 polymorphism and HBV dynamics was also assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study populations

Forty-seven normal controls (normal group), 57 patients with biopsy-proven CHB and NAFLD (CHB + NAFLD group), and 51 patients with only biopsy-proven CHB (CHB group) were recruited between January 2012 and June 2013. Subjects were enrolled from Tianjin Hospital of Infectious Diseases (Northern China, n = 54), Xinhua Hospital (Shanghai, Central China, n = 72), and Zhengxing Hospital (Zhangzhou, Southern China, n = 29). Subjects with the following were excluded: high alcohol intake (> 20 g/d for men and > 10 g/d for women), HCV infection, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, hereditary hemochromatosis, and current or previous treatment that is known to cause steatosis. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Clinical investigations were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Biochemical and anthropometric analysis

Anthropometric parameters of height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were characterized for the study population. A fasting blood sample was collected from each patient and control subject. The serum was separated and stored at -20 °C until required for further analysis. Biochemical tests were performed for measuring the enzyme activities of alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and γ-glutamyltransferase, as well as the level of total bilirubin by standard enzyme methodology using a multichannel automatic analyzer (Advia 1650; Bayer, Moss, Norway). Fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein, and low-density lipoprotein concentrations were analyzed using Wako Bioproducts (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Richmond, VA, United States). The HBV-DNA titer was quantified by real-time PCR (Daangene, Guangzhou, China) on a Light Cycler (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

Hepatic histopathologic assessment

Liver sections of CHB patients with and without NAFLD were obtained by needle biopsy after obtaining informed consent. Liver samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sliced for further evaluation. Hematoxylin-eosin and Masson’s trichrome staining was successively performed. Histologic changes were graded and staged according to the Kleiner classification, and the NAFLD activity score (NAS) was calculated using the grade of steatosis, lobular inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning[21]. NASH was defined by NAS ≥ 5, including a ballooning degeneration score of ≥ 1.

Genotyping of SNPs

All blood samples were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min immediately after sample collection. The buffy-coat layer obtained from each blood sample was separated and transferred into 1.5-mL centrifuge tubes. Genomic DNA was extracted from the concentrated lymphocytes of the buffy coat using QiAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Benlo, Limburg, Netherlands). The custom Ion AmpliSeq panel (Life Technologies of Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) of PNPLA3 was designed, with the overall coverage rate of 89.91%. The emulation PCR of the template was performed using the Ion OneTouch 2 System (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PNPLA3 variants were genotyped by DNA sequencing using the Ion 318 Chip (Life Technologies) following the Ion PGM 200 Sequencing kit protocol. In addition, the LD of PNPLA3 SNPs was investigated by LD and haplotype block analysis using Haploview software (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, United States).

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Odds ratios (ORs) adjusted for age, sex, and BMI were calculated using multivariant logistic regression with genotypes, age, sex, and BMI as the independent variables. The χ2 test was used to assess whether the genotypes were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and to test differences in genotype distribution. Prior to analyzing the data, all the variables were tested for normality, with non-normally distributed variables log-transformed to be better approximated by normality. Differences among the groups of genotypes were tested by analysis of variance using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Guang-Yu Chen from Clinical Epidemiology Center, Shanghai Jiaotong University.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical data

Patients with both NAFLD and CHB demonstrated a signficantly higher BMI than that of the normal group and CHB patients (P < 0.001, Table 1). Patents in the CHB + NAFLD had higher total cholesterol, trigcyleride, low-density lipoprotein and fasting blood glucose than the CHB group (all P < 0.05), and a trend for decreased high-density lipoprotein, indicated impaired glycolipid metabolism in CHB + NAFLD patients independent of CHB (Table 1). The coexistence of CHB, which reflects chronic hepatic inflammation, may provide an explanation for the insignificant difference in alanine aminotransferase activity between the CHB + NAFLD and the CHB groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of all patients

| Variable | Normal group (n = 47) | CHB group (n = 51) | CHB + NAFLD group (n = 57) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 46.74 ± 6.97 | 36.76 ± 12.60 | 38.98 ± 13.55 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | M: 29 (61.70) | M: 34 (66.67) | M: 42 (73.68) | 0.420 |

| F: 18 (38.30) | F: 17 (33.33) | F: 15 (26.32) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.43 ± 2.59 | 22.84 ± 2.97 | 27.40 ± 3.24 | < 0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.40 ± 1.22 | 4.39 ± 0.96 | 4.89 ± 0.84 | 0.023 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.98 ± 0.31 | 1.12 ± 0.38 | 1.84 ± 1.35 | < 0.001 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.51 ± 1.22 | 1.50 ± 0.44 | 1.20 ± 0.28 | 0.142 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.03 ± 0.85 | 2.22 ± 0.56 | 2.94 ± 1.02 | < 0.001 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 3.39 ± 1.30 | 4.11 ± 0.63 | 5.71 ± 1.92 | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 13. 72 ± 4.16 | 76.14 ± 53.70 | 68.51 ± 47.20 | < 0.001 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 2.25 ± 0.51 | 23.78 ± 21.44 | 5.80 ± 3.55 | < 0.001 |

| GGT (U/L) | 16.42 ± 7.31 | 94.33 ± 94.13 | 60.18 ± 36.81 | < 0.001 |

| ALP (U/L) | 16.08 ± 5.48 | 95.23 ± 40.35 | 101.16 ± 88.46 | < 0.001 |

CHB: Chronic hepatitis B; NAFLD: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; BMI: Body mass index; TC: Total cholesterol; TG: Triglyceride; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; FBG: Fasting blood glucose; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; TBIL: Total bilirubin; GGT: γ-glutamyltransferase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase.

Association of PNPLA3 polymorphisms and NAFLD in CHB patients

After genotyping for PNPLA3 polymorphisms, the G allele at rs738409, T allele at rs3747206, A allele at rs4823173, and G allele at rs2072906 were associated with NAFLD in CHB patients when compared with CHB only patients (Table 2). Furthermore, a significant association was found between NAFLD and PNPLA3 SNPs rs738409, rs3747206, rs4823173, and rs2072906 after adjusting for sex and age, or sex, age, and BMI (all P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Association tests of PNPLA3 single nucleotide polymorphisms

| Groups | SNPs |

Group (%) |

OR (95%CI) |

P value |

||||||

| Normal | CHB | CHB + NAFLD | Unadjusted | Adjusted for age, sex | Adjusted for age, sex, and BMI | Unadjusted | Adjusted for age and sex | Adjusted for age, sex, and BMI | ||

| CHB+NAFLD vs CHB | 738409 | C: 57.84G: 42.16 | C: 44.74G: 55.26 | 1.695(0.989-2.906) | 2.334(1.169-4.657) | 2.774(1.176-6.543) | 0.054 | 0.016 | 0.020 | |

| 3747206 | C: 57.84T: 42.16 | C: 44.74T: 55.26 | 1.695(0.989-2.906) | 2.334(1.169-4.657) | 2.774(1.176-6.543) | 0.054 | 0.016 | 0.020 | ||

| 4823173 | G: 58.82A: 41.18 | G: 45.61A: 54.39 | 1.703(0.993-2.922) | 2.134(1.089-4.180) | 2.734(1.161-6.437) | 0.052 | 0.027 | 0.021 | ||

| 2072906 | A: 58.82G: 41.18 | C: 44.74G: 55.26 | 1.765 (1.028-3.029) | 2.314(1.174-4.559) | 3.045(1.277-7.262) | 0.039 | 0.015 | 0.012 | ||

| CHB+NAFLD vs normal | 738409 | C: 63.83G: 36.17 | C: 44.74G: 55.26 | 2.180(1.246-3.815) | 2.529(1.335-4.792) | 3.018(1.318-6.914) | 0.00 | 0.004 | 0.009 | |

| 3747206 | C: 63.83G: 36.17 | C: 44.74T: 55.26 | 2.180(1.246-3.815) | 2.529(1.335-4.792) | 3.018(1.318-6.914) | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.009 | ||

| 4823173 | C: 63.83G: 36.17 | G: 45.61A: 54.39 | 2.104(1.203-3.681) | 2.536(1.329-4.840) | 3.212(1.344-7.679) | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.009 | ||

| 2072906 | C: 63.83G: 36.17 | C: 44.74G: 55.26 | 2.180(1.246-3.815) | 2.684(1.403-5.134) | 3.499(1.452-8.430) | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.005 | ||

| CHB vs normal | 738409 | C: 63.83G: 36.17 | C: 57.84G: 42.16 | 1.286( 0.723-2.287) | 1.356(0.695-2.643) | 1.315(0.674-2.567) | 0.391 | 0.372 | 0.422 | |

| 3747206 | C: 63.83G: 36.17 | C: 57.84T: 42.16 | 1.286(0.723-2.287) | 1.356(0.695-2.643) | 1.315(0.674-2.567) | 0.391 | 0.372 | 0.422 | ||

| 4823173 | C: 63.83G: 36.17 | G: 58.82A: 41.18 | 1.235(0.694-2.199) | 1.439(0.717-2.889) | 1.325(0.652-2.694) | 0.472 | 0.306 | 0.437 | ||

| 2072906 | C: 63.83G: 36.17 | G: 58.82A: 41.18 | 1.235(0.694-2.199) | 1.439(0.717-2.889) | 1.325(0.652-2.694) | 0.472 | 0.306 | 0.437 | ||

BMI: Body mass index; CHB: Chronic hepatitis B; CI: Confidence interval; NAFLD: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; OR: Odds ratio; SNPs: Single nucleotide polymorphisms.

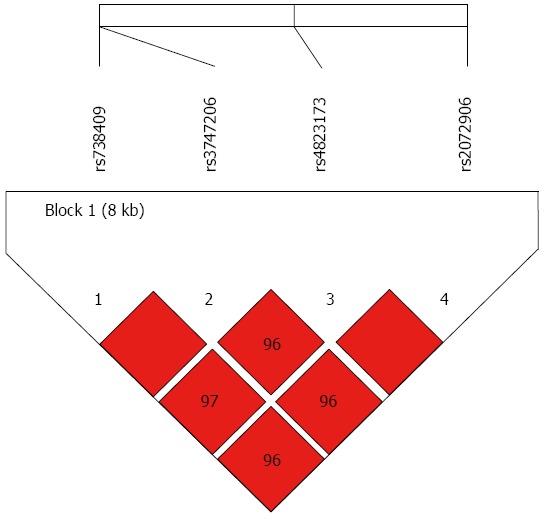

Surprisingly, haplotype block LD mapping showed that SNPs of rs738409, rs3747206, rs4823173, and rs2072906 were in tight LD in an 8-kb sequence (Figure 1). In contrast, the percentage of G allele at rs738409, T allele at rs3747206, A allele at rs4823173, and G allele at rs2072906 was similar between the normal and CHB groups, regardless of age, sex and BMI adjustment.

Figure 1.

Block for liver disease of PNPLA3 single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

Quantitative phenotypes with PNPLA3 polymorphisms

The normal, CHB, and CHB + NAFLD groups were stratified by PNPLA3 genotypes and subjected to demographic and clinical comparisons. In the normal group, subjects bearing G/G allele at rs738409, T/T allele at rs3747206, A/A allele at rs4823173, and G/G allele at rs2072906 demonstrated low-density lipoprotein (P = 0.01-0.06) and fasting blood glucose (P = 0.01-0.02) levels higher than those with C/C or C/G alleles at rs738409, C/C or C/T alleles at rs3747206, G/G or G/A alleles at rs4823173, and A/A or A/G alleles at rs2072906 (Table S1). These subjects were characterized by an increasing trend in total cholesteral levels and decreasing trend in high-density lipoprotein levels (Table S1).

Despite the lack of statistical significance, CHB patients with or without NAFLD carrying the G allele at rs738409, T allele at rs3747206, A allele at rs4823173, and G allele at rs2072906 also exhibited higher levels of triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein, and fasting blood glucose than those with the C allele at rs738409, C allele at rs3747206, G allele at rs4823173, and A allele at rs2072906 (Table S1). Thus, rs738409 (G allele), rs3747206 (T allele), rs4823173 (A allele), and rs2072906 (G allele) may be involved in glycolipid metabolism.

Correlation between PNPLA3 polymorphisms and pathologic characteristics

Association of PNPLA3 SNPs with the histologic features of NAFLD, including hepatocyte steatosis, lobular inflammation, hepatocellular ballooning, and liver fibrosis, were analyzed in the CHB + NAFLD group. As compared to those with C/C or C/G alleles at rs738409, C/C or C/T alleles at rs3747206, G/G or G/A alleles at rs4823173, and A/A or A/G alleles at rs2072906, CHB patients harboring the G/G allele at rs738409, T/T allele at rs3747206, A/A allele at rs4823173, and G/G allele at rs2072906 showed increased risk of hepatocellular ballooning (ballooning > 1; P = 0.01-0.03) and NASH (NAS ≥ 3; P = 0.01-0.03), but not with histologic features of steatosis and inflammation (Table 3). Another striking observation was the significant association between rs738409, rs3747206, rs4823173 and rs2072906 of PNPLA3 and fibrogenesis. CHB + NAFLD patients with the G/G allele at rs738409, T/T allele at rs3747206, A/A allele at rs4823173, and G/G allele at rs2072906 were more susceptible to liver fibrosis (> 1 Metavir grading; P = 0.01-0.04) than those with heterozygote or homozygote C alleles at rs738409, C alleles at rs3747206, G alleles at rs4823173, and A alleles at rs2072906 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association tests of PNPLA3 single nucleotide polymorphisms with histological features in chronic hepatitis B + nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients

| Condition |

PNPLA3 genotype |

P value | ||

| CC (n = 12) | CG (n = 27) | GG (n = 18) | ||

| Steatosis | rs738409: CC | rs738409: CG | rs738409: GG | rs738409: 0.384; |

| M: ≤ 1: 5 (41.67%); | M: ≤ 1: 11 (40.74%); | M: ≤ 1: 4 (22.22%); | rs3747206: 0.384; | |

| F: > 1: 7 (58.33%) | F: > 1: 16 (59.26%) | F: > 1: 14 (77.73%) | rs4823173: 0.374; | |

| rs3747206: CC | rs3747206: CT | rs3747206: TT | rs2072906: 0.275 | |

| M: ≤ 1: 5 (41.67%); | M: ≤ 1: 11 (40.74%); | M: ≤ 1: 4 (22.22%); | ||

| F: > 1: 7 (58.33%) | F: > 1: 16 (59.26%) | F: > 1: 14 (77.73%) | ||

| rs4823173: GG | rs4823173: GA | rs4823173: AA | ||

| M: ≤ 1: 5 (38.46%); | M: ≤ 1: 11 (42.31%); | M: ≤ 1: 4 (22.22%); | ||

| F: > 1: 8 (61.54%) | F: > 1: 15 (57.69%) | F: > 1: 14 (77.73%) | ||

| rs2072906: AA | rs2072906: AG | rs2072906: GG | ||

| M: ≤ 1: 5 (38.46%); | M: ≤ 1: 11 (44.00%); | M: ≤ 1: 4 (21.05%); | ||

| F: >1: 8 (61.54%) | F: > 1: 14 (56.00%) | F: > 1: 15 (78.95%) | ||

| Lobular inflammation | rs738409: CC | rs738409: CG | rs738409: GG | rs738409: 0.706; |

| M: ≤ 1: 5 (41.67%); | M: ≤ 1: 10 (37.04%); | M: ≤ 1: 5 (27.78%); | rs3747206: 0.706; | |

| F: > 1: 7 (58.33%) | F: > 1: 17 (62.96%) | F: > 1: 13 (72.22%) | rs4823173: 0.570; | |

| rs3747206: CC | rs3747206: CT | rs3747206: TT | rs2072906: 0.509 | |

| M: ≤ 1: 5 (41.67%); | M: ≤ 1: 10 (37.04%); | M: ≤ 1: 5 (27.78%); | ||

| F: > 1: 7 (58.33%) | F: > 1: 17 (62.96%) | F: > 1: 13 (72.22%) | ||

| rs4823173: GG | rs4823173: GA | rs4823173: AA | ||

| M: ≤ 1: 6 (46.15%); | M: ≤ 1: 9 (34.62%); | M: ≤ 1: 5 (27.78%); | ||

| F: > 1: 7 (53.85%) | F: > 1: 17 (65.38%) | F: > 1: 13 (72.22%) | ||

| rs2072906: AA | rs2072906: AG | rs2072906: GG | ||

| M: ≤ 1: 6 (46.15%); | M: ≤ 1: 9 (36.00%); | M: ≤ 1: 5 (26.32%); | ||

| F: > 1: 7 (53.85%) | F: > 1: 16 (64.00%) | F: > 1: 14 (73.68%) | ||

| Ballooning | rs738409: CC | rs738409: CG | rs738409: GG | rs738409: 0.021 |

| M: ≤ 1: 6 (50.0%); | M: ≤ 1: 9 (33.33%); | M: ≤ 1: 1 (5.56%); | (CC vs GG: P = 0.005; CG vs GG: P = 0.028); | |

| F: > 1: 6 (50.0%) | F: > 1: 18 (66.67%) | F: > 1: 17 (94.44%) | rs3747206: 0.021 | |

| rs3747206: CC | rs3747206: CT | rs3747206: TT | (CC vs TT: P = 0.005; CT vs TT: P = 0.028); | |

| M: ≤ 1: 6 (50.00%); | M: ≤ 1: 9 (33.33%); | M: ≤ 1: 1 (5.56%); | rs4823173: 0.012 | |

| F: > 1: 6 (50.00%) | F: > 1: 18 (66.67%) | F: > 1: 17 (94.44%) | (GG vs AA: P = 0.002; GA vs AA: P = 0.041); | |

| rs4823173: GG | rs4823173: GA | rs4823173: AA | rs2072906: 0.009 | |

| M: ≤ 1: 7 (53.85%); | M: ≤ 1: 8 (30.77%); | M: ≤ 1: 1 (5.56%); | (AA vs GG: P = 0.002; AG vs GG: P = 0.029) | |

| F: > 1: 6 (46.15%) | F: > 1: 18 (69.23%) | F: > 1: 17 (94.44%) | ||

| rs2072906: AA | rs2072906: AG | rs2072906: GG | ||

| M: ≤ 1: 7 (53.85%); | M: ≤ 1: 8 (32.0%); | M: ≤ 1: 1 (5.26%); | ||

| F: > 1: 6 (46.15%) | F: > 1: 17 (68.0%) | F: > 1: 18 (94.74%) | ||

| NAS | rs738409: CC | rs738409: CG | rs738409: GG | rs738409: 0.039 |

| M: < 3: 10 (83.33%); | M: < 3: 11 (40.74%); | M: < 3: 8 (44.44%); | (CC vs CG: P = 0.014; CC vs GG: P = 0.033); | |

| F: ≥ 3: 2 (16.67%) | F: ≥ 3: 16 (59.26%) | F: ≥ 3: 10 (55.56%) | rs3747206: 0.039 | |

| rs3747206: CC | rs3747206: CT | rs3747206: TT | (CC vs CG: P = 0.014; CC vs GG: P = 0.033); | |

| M: < 3: 10 (83.33%); | M: < 3: 11 (40.74%); | M: < 3: 8 (44.44%); | rs4823173: 0.020 | |

| F: ≥ 3: 2 (16.67%) | F: ≥ 3: 16 (59.26%) | F: ≥ 3: 10 (55.56%) | (GG vs GA: P = 0.006; GG vs AA: P = 0.023); | |

| rs4823173: GG | rs4823173: GA | rs4823173: AA | rs2072906: 0.021 | |

| M: < 3: 11 (84.62%); | M: < 3: 10 (38.46%); | M: < 3: 8 (44.44%); | (AA vs AG: P = 0.009; AA vs GG: P = 0.016) | |

| F: ≥ 3: 2 (15.38%) | F: ≥ 3: 16 (61.54%) | F: ≥ 3: 10 (55.56%) | ||

| rs2072906: AA | rs2072906: AG | rs2072906: GG | ||

| M: < 3: 11 (84.62%); | M: < 3: 10 (40.0%); | M: < 3: 8 (42.11%); | ||

| F: ≥ 3: 2 (15.38%) | F: ≥ 3: 15 (60.0%) | F: ≥3: 11 (57.89%) | ||

| Fibrosis grading | rs738409: CC | rs738409: CG | rs738409: GG | rs738409: 0.032 |

| M: ≤ 1: 11 (91.67%); | M: ≤ 1: 17 (62.96%); | M: ≤ 1: 8 (44.44%); | (CC vs GG: P = 0.009); | |

| F: > 1: 1 (8.33%) | F: > 1: 10 (37.04%) | F: > 1: 10 (55.56%) | rs3747206: 0.032 | |

| rs3747206: CC | rs3747206: CT | rs3747206: TT | (CC vs TT: P= 0.009); | |

| M: ≤ 1: 11 (91.67%); | M: ≤ 1: 17 (62.96%); | M: ≤ 1: 8 (44.44%); | rs4823173: 0.024 | |

| F: > 1: 1 (8.33%) | F: > 1: 10 (37.04%) | F: > 1: 10 (55.56%) | (GG vs GA: P = 0.044; GG vs AA: P = 0.006); | |

| rs4823173: GG | rs4823173: GA | rs4823173: AA | rs2072906: 0.015 | |

| M: ≤ 1: 12 (92.31%); | M: ≤ 1: 16 (61.54%); | M: ≤ 1: 8 (44.44%); | (AA vs GG: P = 0.004) | |

| F: > 1: 1 (7.69%) | F: > 1: 10 (38.46%) | F: > 1: 10 (55.56%) | ||

| rs2072906: AA | rs2072906: AG | rs2072906: GG | ||

| M: ≤ 1: 12 (92.31%); | M: ≤ 1: 16 (64.0%); | M: ≤ 1: 8 (42.11%); | ||

| F: > 1: 1 (7.69%) | F: > 1: 9 (36.0%) | F: > 1: 11 (57.89%) | ||

NAS: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score.

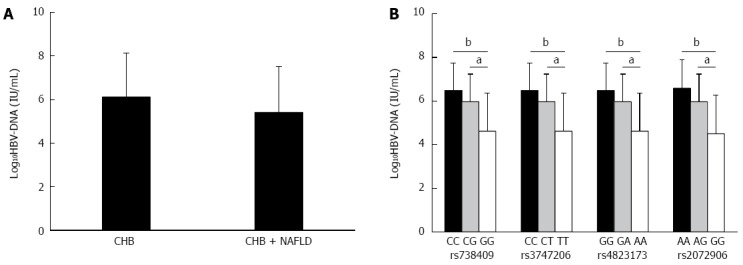

Effect of PNPLA3 polymorphisms on HBV dynamics

As defined by the serum level of HBV DNA, patients in the CHB + NAFLD and CHB groups showed active viral replication. However, there was a decreasing trend in HBV-DNA levels in the CHB + NAFLD patients (Figure 2A). In the CHB + NAFLD group, patients bearing the G/G allele at rs7384096, T/T allele at rs3747206, A/A allele at rs4823173, and G/G allele at rs2072906 were characterized by an HBV-DNA level lower than the patients with C/C or C/G alleles at rs738409, C/C or C/T alleles at rs3747206, G/G or G/A alleles at rs4823173, and A/A or A/G alleles at rs2072906 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Association of PNPLA3 SNPs and serum HBV-DNA level. A: Comparison of serum HBV-DNA level between CHB + NAFLD and CHB patients; B: Association of PNPLA3 SNPs and serum level of HBV-DNA in CHB + NAFLD patients. CHB: Chronic hepatitis B; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; NAFLD: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; SNP: Single-nucleotide polymorphism. aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

PNPLA3 is a hepatocyte-located adiponutrin, and has recently been shown to influence genetic predisposition to NAFLD[22-24]. A commonly prevalent PNPLA3 SNP, the rs738409 G allele, contributes to the increased liver fat content in various populations[4-6,11,25], regardless of sex[5], age[26,27], or underlying diseases[6,28]. Moreover, association studies have confirmed that patients carrying the rs738409 SNP of PNPLA3 are susceptible to NASH[7,25,29,30] and liver fibrosis[25,31-33]. There are similar findings for multiple PNPLA3 SNPs, including rs2281135, rs139051, rs2294918, and rs6006460[10-13]. Therefore, polymorphism of PNPLA3 plays an important role in the development of a full spectrum of NAFLDs, which includes simple steatosis, steatohepatitis, and liver fibrosis. Mechanistically, the effect of PNPLA3 polymorphism on NAFLD has been attributed to abnormalities in plasma alanine and aspartate transaminase and ferritin levels[9,10,22,31], and abdominal fat (waist circumference-to-height ratio above 0.62)[9]. However, the PNPLA3-mediated liver enzyme change is independent of obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolism syndrome[29]. The rs738409 G allele of PNPLA3 is even associated with decreased triglyceride levels in NAFLD patients of Malaysia[34].

In the present study, PNPLA3 polymorphisms (rs738409, rs3747206, rs4823173, and rs2072906) were strongly associated with susceptibility to NAFLD in CHB patients from Northern, Central, and Southern China. This effect was independent of age, sex and BMI. Strikingly, these four SNPs were present in an 8-kb sequence of PNPLA3 and showed strong LD with each other. When evaluated by NAS score (≥ 3), CHB patients with the rs738409 G allele, rs3747206 T allele, rs4823173 A allele, and rs2072906 G allele had greater susceptibility to suspected NASH or NASH than those with the rs738409 C allele, rs3747206 C allele, rs4823173 G allele, and rs2072906 A allele. These findings demonstrate that the role of PNPLA3 polymorphisms in CHB patients is consistent with that in general population[11,24,32,35]. Thus, in contrast to the HCV-induced hepatocyte steatosis in chronic hepatitis C patients, host metabolism, rather than viral infection, is responsible for the development of fatty liver disease, especially NASH, in CHB patients.

rs738409, rs3747206, rs4823173, and rs2072906 of PNPLA3 were not significantly associated with histologic parameters of NAFLD (steatosis and lobular inflammation), with the exception of ballooning. With regard to hepatosteatosis, there are conflicting reports concerning the correlation between hepatocyte steatosis and PNPLA3 polymorphisms. The rs738409 G allele of PNPLA3 was previously associated with steatosis grade in NAFLD patients in Italy and Japan[25,28], and with hepatic fat content in NAFLD patients in different ethnic subgroups (Caucasians, African Americans, and Hispanics) and different ages (children, adolescents and adults) in the United States[26,27]. However, the correlation between steatosis and rs738409 was not confirmed in four other groups of NAFLD patients from Malaysia, Northern Europe, and Japan[20,29,31,34]. Ethnic subgroups of Chinese, Indian, Malay, Japanese, Danish, Norwegian, Finnish, and Swedish populations were included in these studies. Similarly, PNPLA3 polymorphism does not affect the lobular inflammation in Chinese, Indian, and Malay individuals with NAFLD[29]. On the basis of the slightly higher prevalence of hepatic steatosis and lobular inflammation, together with the prominent liver ballooning in subjects with the G allele at rs738409, T allele at rs3747206, A allele at rs4823173, and G allele at rs2072906, we speculate that the accumulated effect of PNPLA3 polymorphisms on pathologic characteristics may influence the occurrence of NAFLD in CHB patients.

Another noticeable result lies in the effect of PNPLA3 polymorphisms on liver fibrosis. Liver fibrosis is one of the clinical outcomes of NAFLD[7], thus, most patients from the CHB + NAFLD group showed liver fibrosis, regardless of PNPLA3 genotype. Perisinusoidal and portal fibrosis characterized their pathologic disorders on the basis of hepatosteatosis, ballooning, and lobular inflammation. Progressive liver fibrosis (> 1 Metavir grading), however, prevailed in CHB + NAFLD patients carrying G/G allele at rs738409 (C/C vs G/G: P < 0.01), T/T allele at rs3747206 (C/C vs T/T: P < 0.01), A/A allele at rs4823173 (G/G vs A/A: P < 0.01; G/G vs G/A: P < 0.05), and G/G allele at rs2072906 (A/A vs G/G: P < 0.05). These results suggest that PNPLA3 polymorphism is a critical factor in the progression of NAFLD-related fibrosis in CHB patients, which is in accordance with previous reports in general populations[29,31]. NASH is the key step from simple steatosis to liver fibrosis. Therefore, the association between PNPLA3 polymorphisms and liver fibrosis may be attributed to severe NASH correlating with rs738409, rs3747206, rs4823173, and rs2072906.

In addition to the interaction between PNPLA3 polymorphisms and hepatic pathologic parameters, four linked SNPs of PNPLA3 exhibited a striking association with viral dynamics in our study. When compared to that of CHB patients, the serum level of HBV-DNA showed a decreasing trend in patients with NAFLD and CHB. Furthermore, there was a significant reduction of log10 HBV-DNA in CHB + NAFLD patients with the G/G allele at rs738409, T/T allele at rs3747206, A/A allele at rs4823173, and G/G allele at rs2072906. PNPLA3 polymorphisms seem to serve as the negative regulator of HBV replication.

NAFLD and CHB have been shown to share a common mechanism, namely, abnormality in the Toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated innate immune response[35-38]. Suppression of the innate immune response in parenchymal and nonparenchymal liver cells underlies chronic infection with HBV[35]. In contrast, TLR4, one of the members of pattern recognition receptor family, is activated by lipopolysaccharide in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells during high-fat diet-induced NAFLD[35-37]. Activation of TLR4 initiates the innate immune response via MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent signaling pathways. In patients with both NAFLD and CHB, inhibition of the TLR4-dependent innate immune system could be reactivated. Upregulation of TLR4/MyD88 signaling promotes the expression of various inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-α[39-42]. Replication of HBV, evaluated by HBV covalently closed circular DNA, is then repressed by tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, partially via oxidative stress and inhibition of regulatory T cells[39-43]. In agreement with our findings, NAFLD-based downregulation of viral replication has been confirmed in a clinical trial of chronic hepatitis C patients[20] and a transgenic mouse model of HBV[44].

In summary, linked SNPs of PNPLA3 (rs738409, rs3747206, rs4823173, rs2072906) are correlated with susceptibility to NAFLD, NASH, and liver fibrosis in Chinese CHB patients. In addition to fatty liver disease, these PNPLA3 polymorphisms may exert an inhibitory effect on HBV-DNA level.

COMMENTS

Background

With the increasing prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become a commonly occurring liver disease and a public health burden in most areas of China. The high prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in the Chinese population causes concurrent NAFLD and chronic hepatitis B (CHB). Previous studies have indicated that PNPLA3 polymorphisms play an important role in the development of NAFLD. However, the role of the PNPLA3 polymorphism in patients with both NAFLD and CHB has not yet been established.

Research frontiers

PNPLA3 is a hepatocyte-located adiponutrin, and has recently been shown to influence genetic predisposition to NAFLD. In patients with concurrent CHB and NAFLD, the research hotspot lies in uncovering the association of PNPLA3 polymorphisms with clinical, laboratory, and pathologic characteristics of NAFLD, and also with HBV dynamics.

Innovations and breakthroughs

To shed light on the effect of PNPLA3, a cohort of Han patients with biopsy-proven CHB, with or without NAFLD, and normal controls were enrolled from Northern (Tianjin), Central (Shanghai), and Southern (Zhangzhou) China. Their PNPLA3 polymorphisms were genotyped by gene sequencing. The association between PNPLA3 polymorphisms and susceptibility to NAFLD, and clinical characteristics of NAFLD were assessed on the basis of physical indices, liver function tests, glycolipid metabolism, and histopathologic scoring. Association of PNPLA3 polymorphisms and HBV load was determined by serum level of HBV-DNA. This study found that four linked single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of PNPLA3 (rs738409 G allele, rs3747206 T allele, rs4823173 A allele, and rs2072906 G allele) conferred susceptibility to NAFLD, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and liver fibrosis in CHB patients. Patients carrying these SNPs showed significantly lower serum levels of HBV-DNA.

Applications

The results suggest that four linked SNPs of PNPLA3 (rs738409, rs3747206, rs4823173, and rs2072906) are correlated with susceptibility to NAFLD, NASH, and liver fibrosis in CHB patients. These PNPLA3 polymorphisms may play a regulatory role in HBV dynamics.

Terminology

PNPLA3 is a gene on chromosome 22q13, which encodes adiponutrin, a protein with triacylglycerol hydrolase and acylglycerol transacetylase activity in hepatocytes. SNPs in PNPLA3, such as rs738409 C>G, result in an adiponutrin variant with I148M (isoleucine-to-methionine substitution at residue 148), which has been identified as a predisposing factor for liver steatosis.

Peer-review

This is an interesting work on the effect of PNPLA3 polymorphisms and their association with NAFLD/NASH and HBV viral load in patients with CHB. The work is well designed, performed, and analyzed, and the findings are clear and well presented in the Results section and Figures.

Footnotes

Supported by State Key Development Program for Basic Research of China, No. 2012CB517501; National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81070322, No. 81270491 and No. 81470840; 100 Talents Program, No. XBR2011007h; and Program of the Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology, No. 09140903500 and No. 13ZR14267.

Institutional review board statement: This paper was approved by the Xinhua Hospital Ethics Committee Affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine.

Institutional animal care and use committee statement: No animal has been employed in the experiments relating to manuscript of “Linked polymorphisms of PNPLA3 confer susceptibility to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and decreased viral load in chronic hepatitis B”.

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflict of interest is declared for each author of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at fattyliver2004@126.com. Participants gave informed consent for data sharing.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: January 24, 2015

First decision: February 10, 2015

Article in press: April 17, 2015

P- Reviewer: Alexopoulou A S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Fan JG, Jia JD, Li YM, Wang BY, Lu LG, Shi JP, Chan LY. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: update 2010: (published in Chinese on Chinese Journal of Hepatology 2010; 18: 163-166) J Dig Dis. 2011;12:38–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Day CP, James OF. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842–845. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vuppalanchi R, Chalasani N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Selected practical issues in their evaluation and management. Hepatology. 2009;49:306–317. doi: 10.1002/hep.22603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krarup NT, Grarup N, Banasik K, Friedrichsen M, Færch K, Sandholt CH, Jørgensen T, Poulsen P, Witte DR, Vaag A, et al. The PNPLA3 rs738409 G-allele associates with reduced fasting serum triglyceride and serum cholesterol in Danes with impaired glucose regulation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nobili V, Liccardo D, Bedogni G, Salvatori G, Gnani D, Bersani I, Alisi A, Valenti L, Raponi M. Influence of dietary pattern, physical activity, and I148M PNPLA3 on steatosis severity in at-risk adolescents. Genes Nutr. 2014;9:392. doi: 10.1007/s12263-014-0392-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guichelaar MM, Gawrieh S, Olivier M, Viker K, Krishnan A, Sanderson S, Malinchoc M, Watt KD, Swain JM, Sarr M, et al. Interactions of allelic variance of PNPLA3 with nongenetic factors in predicting nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and nonhepatic complications of severe obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:1935–1941. doi: 10.1002/oby.20327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valenti L, Al-Serri A, Daly AK, Galmozzi E, Rametta R, Dongiovanni P, Nobili V, Mozzi E, Roviaro G, Vanni E, et al. Homozygosity for the patatin-like phospholipase-3/adiponutrin I148M polymorphism influences liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:1209–1217. doi: 10.1002/hep.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu YL, Patman GL, Leathart JB, Piguet AC, Burt AD, Dufour JF, Day CP, Daly AK, Reeves HL, Anstee QM. Carriage of the PNPLA3 rs738409 C & gt; G polymorphism confers an increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;61:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giudice EM, Grandone A, Cirillo G, Santoro N, Amato A, Brienza C, Savarese P, Marzuillo P, Perrone L. The association of PNPLA3 variants with liver enzymes in childhood obesity is driven by the interaction with abdominal fat. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q, Qu HQ, Rentfro AR, Grove ML, Mirza S, Lu Y, Hanis CL, Fallon MB, Boerwinkle E, Fisher-Hoch SP, et al. PNPLA3 polymorphisms and liver aminotransferase levels in a Mexican American population. Clin Invest Med. 2012;35:E237–E245. doi: 10.25011/cim.v35i4.17153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng XE, Wu YL, Lin SW, Lu QQ, Hu ZJ, Lin X. Genetic variants in PNPLA3 and risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a Han Chinese population. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speliotes EK, Butler JL, Palmer CD, Voight BF, Hirschhorn JN. PNPLA3 variants specifically confer increased risk for histologic nonalcoholic fatty liver disease but not metabolic disease. Hepatology. 2010;52:904–912. doi: 10.1002/hep.23768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, Boerwinkle E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1461–1465. doi: 10.1038/ng.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang FS, Fan JG, Zhang Z, Gao B, Wang HY. The global burden of liver disease: the major impact of China. Hepatology. 2014;60:2099–2108. doi: 10.1002/hep.27406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan JG, Farrell GC. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in China. J Hepatol. 2009;50:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsochatzis E, Papatheodoridis GV, Manesis EK, Chrysanthos N, Kafiri G, Archimandritis AJ. Hepatic steatosis in chronic hepatitis B develops due to host metabolic factors: a comparative approach with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:936–942. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.07.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yun JW, Cho YK, Park JH, Kim HJ, Park DI, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI, Son BH, Shin JH. Hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in young men with treatment-naïve chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2009;29:878–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong VW, Wong GL, Chu WC, Chim AM, Ong A, Yeung DK, Yiu KK, Chu SH, Chan HY, Woo J, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection and fatty liver in the general population. J Hepatol. 2012;56:533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi JP, Fan JG, Wu R, Gao XQ, Zhang L, Wang H, Farrell GC. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatic steatosis and its impact on liver injury in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1419–1425. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rembeck K, Maglio C, Lagging M, Christensen PB, Färkkilä M, Langeland N, Buhl MR, Pedersen C, Mørch K, Norkrans G, et al. PNPLA 3 I148M genetic variant associates with insulin resistance and baseline viral load in HCV genotype 2 but not in genotype 3 infection. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrell GC, Chitturi S, Lau GK, Sollano JD. Guidelines for the assessment and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Asia-Pacific region: executive summary. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:775–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Xing C, Tian Z, Ku HC. Genetic variant I148M in PNPLA3 is associated with the ultrasonography-determined steatosis degree in a Chinese population. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Y, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Expression and characterization of a PNPLA3 protein isoform (I148M) associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:37085–37093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.290114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Xing C, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Genetic variant in PNPLA3 is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in China. Hepatology. 2012;55:327–328. doi: 10.1002/hep.24659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawaguchi T, Sumida Y, Umemura A, Matsuo K, Takahashi M, Takamura T, Yasui K, Saibara T, Hashimoto E, Kawanaka M, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of the human PNPLA3 gene are strongly associated with severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Japanese. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santoro N, Kursawe R, D’Adamo E, Dykas DJ, Zhang CK, Bale AE, Calí AM, Narayan D, Shaw MM, Pierpont B, et al. A common variant in the patatin-like phospholipase 3 gene (PNPLA3) is associated with fatty liver disease in obese children and adolescents. Hepatology. 2010;52:1281–1290. doi: 10.1002/hep.23832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santoro N, Savoye M, Kim G, Marotto K, Shaw MM, Pierpont B, Caprio S. Hepatic fat accumulation is modulated by the interaction between the rs738409 variant in the PNPLA3 gene and the dietary omega6/omega3 PUFA intake. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valenti L, Rametta R, Ruscica M, Dongiovanni P, Steffani L, Motta BM, Canavesi E, Fracanzani AL, Mozzi E, Roviaro G, et al. The I148M PNPLA3 polymorphism influences serum adiponectin in patients with fatty liver and healthy controls. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zain SM, Mohamed R, Mahadeva S, Cheah PL, Rampal S, Basu RC, Mohamed Z. A multi-ethnic study of a PNPLA3 gene variant and its association with disease severity in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hum Genet. 2012;131:1145–1152. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1141-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sookoian S, Castaño GO, Burgueño AL, Gianotti TF, Rosselli MS, Pirola CJ. A nonsynonymous gene variant in the adiponutrin gene is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease severity. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:2111–2116. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P900013-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hotta K, Yoneda M, Hyogo H, Ochi H, Mizusawa S, Ueno T, Chayama K, Nakajima A, Nakao K, Sekine A. Association of the rs738409 polymorphism in PNPLA3 with liver damage and the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:172. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotman Y, Koh C, Zmuda JM, Kleiner DE, Liang TJ. The association of genetic variability in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) with histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52:894–903. doi: 10.1002/hep.23759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valenti L, Alisi A, Galmozzi E, Bartuli A, Del Menico B, Alterio A, Dongiovanni P, Fargion S, Nobili V. I148M patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 gene variant and severity of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52:1274–1280. doi: 10.1002/hep.23823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura M, Kanda T, Nakamoto S, Miyamura T, Jiang X, Wu S, Yokosuka O. No correlation between PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype and fatty liver and hepatic cirrhosis in Japanese patients with HCV. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu J, Meng Z, Jiang M, Pei R, Trippler M, Broering R, Bucchi A, Sowa JP, Dittmer U, Yang D, et al. Hepatitis B virus suppresses toll-like receptor-mediated innate immune responses in murine parenchymal and nonparenchymal liver cells. Hepatology. 2009;49:1132–1140. doi: 10.1002/hep.22751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye D, Li FY, Lam KS, Li H, Jia W, Wang Y, Man K, Lo CM, Li X, Xu A. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates obesity-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis through activation of X-box binding protein-1 in mice. Gut. 2012;61:1058–1067. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spruss A, Kanuri G, Wagnerberger S, Haub S, Bischoff SC, Bergheim I. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in the development of fructose-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. Hepatology. 2009;50:1094–1104. doi: 10.1002/hep.23122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Csak T, Velayudham A, Hritz I, Petrasek J, Levin I, Lippai D, Catalano D, Mandrekar P, Dolganiuc A, Kurt-Jones E, et al. Deficiency in myeloid differentiation factor-2 and toll-like receptor 4 expression attenuates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G433–G441. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00163.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Togashi H, Ohno S, Matsuo T, Watanabe H, Saito T, Shinzawa H, Takahashi T. Interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin 1-beta suppress the replication of hepatitis B virus through oxidative stress. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 2000;107:407–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi H, Lu L, Zhang NP, Zhang SC, Shen XZ. Effect of interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α on hepatitis B virus following lamivudine treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3617–3622. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i27.3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoop JN, Woltman AM, Biesta PJ, Kusters JG, Kuipers EJ, Janssen HL, van der Molen RG. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibits the suppressive effect of regulatory T cells on the hepatitis B virus-specific immune response. Hepatology. 2007;46:699–705. doi: 10.1002/hep.21761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuo TM, Hu CP, Chen YL, Hong MH, Jeng KS, Liang CC, Chen ML, Chang C. HBV replication is significantly reduced by IL-6. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:41. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Busca A, Kumar A. Innate immune responses in hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Virol J. 2014;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Z, Pan Q, Duan XY, Liu Q, Mo GY, Rao GR, Fan JG. Fatty liver reduces hepatitis B virus replication in a genotype B hepatitis B virus transgenic mice model. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1858–1864. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]