Abstract

Assembly of the T cell receptor (TCR) with its dimeric signaling modules, CD3δε, CD3γε, and ζζ, is organized by transmembrane (TM) interactions. Each of the three assembly steps requires formation of a three-helix interface involving one particular basic TCR TM residue and two acidic TM residues of the respective signaling dimer. The extracellular domains of CD3δε and CD3γε contribute to assembly, but TCR interaction sites on CD3 dimers have not been defined. The structures of the extra-cellular domains of CD3δε and CD3γε demonstrated parallel β-strands ending at the first cysteine in the CXXCXEXXX motif present in the stalk segment of each CD3 chain. Mutation of the membrane-proximal cysteines impaired assembly of either CD3 dimer with TCR, and little complex was isolated when all four membrane-proximal cysteines were mutated to alanine. These mutations had, however, no discernable effect on CD3δε or CD3γε dimerization. CD3δε assembled with a TCRα mutant that lacked both immunoglobulin domains, but shortening of the TCRα connecting peptide reduced assembly, consistent with membrane-proximal TCRα-CD3δε interactions. Chelation of divalent cations did not affect assembly, indicating that coordination of a cation by the tetracysteine motif was not required. The membrane-proximal cysteines were within close proximity but only formed covalent CD3 dimers when one cys-teine was mutated. The four cysteines may thus form two intra-chain disulfide bonds integral to the secondary structure of CD3 stalk regions. The three-chain interaction theme first established for the TM domains thus extends into the membrane-proximal domains of TCRα-CD3δε and TCRβ-CD3γε.

The T cell receptor (TCR)3 controls T cell development and function and is assembled from six distinct component polypeptides into an eight-chain complex. The TCR heterodimer is responsible for ligand recognition but lacks cytoplasmic signaling domains. Instead, it associates through non-covalent interactions with three dimeric signaling modules, CD3δε, CD3γε, and ζζ (1–11). The ζ chain only has a short nine-amino acid extracellular domain and forms covalent dimers through a cysteine at position 2 of the predicted trans-membrane (TM) domain (3, 12, 13). The CD3γ, -δ, and -ε chains have more substantial extracellular components, and their Ig domains form noncovalent heterodimers through parallel β-strands, which create a β-sheet along the dimer interface. In each CD3 chain, a nine-amino acid segment with a highly conserved CXXCXEXXX motif connects this β-strand to the TM domain (1, 14–18).

Assembly of the TCR heterodimer with the three dimeric signaling modules requires proper placement of a total of nine ionizable TM residues, the three basic TM residues of the TCR heterodimer (7, 19) and a pair of acidic TM residues in each signaling module (4). Each basic TCR TM residue serves a specific role in the assembly process; lysine residues located close to the center of the TM domains of TCRα and TCRβ serve as interaction sites for the CD3δε and CD3γε dimers, respectively, whereas the arginine in the N-terminal third of the TCRα TM domain interacts with the ζζ dimer (4). The formation of these three-chain TM interactions requires both acidic residues of each signaling module, because substitution of only one of these acidic residues greatly diminishes or abolishes complex formation (4, 20).

Several lines of evidence suggest contributions of the CD3 extracellular domains to assembly of TCR-CD3 complexes, but the location and precise nature of these interaction sites on CD3 dimers remain unknown. Global approaches have demonstrated physical proximity between TCR constant domains and CD3 dimers. Chemical cross-linking experiments demonstrated an interaction between TCRβ and CD3γ (21), a result consistent with the TM interaction of the acidic CD3γε residues and the TCRβ lysine (4, 22). Furthermore, a mAb (H57) that binds to the TCR Cβ FG loop was shown to reduce subsequent staining with a CD3ε mAb (2C11) (23). Steric hindrance between these two mAbs does not provide fine resolution due to the fact that Fab fragments are similar in size to the entire TCRαβ ectodomain.

TCRαβ-CD3 complexes contain only one copy of each CD3 dimer, despite the similarity of the lysine-based TM interaction sites for CD3δε and CD3γε (4, 24, 25). At least two mechanisms contribute to the specific requirement for both CD3 dimers; the TCRα chain has a strong preference for interaction with CD3δε, and efficient interaction of CD3γε with TCRβ requires prior association of TCRα and CD3δε (4). A contribution of the CD3γ extracellular domains to specificity of assembly was shown by domain exchange; a CD3γ mutant with the TM domain of CD3δ was incorporated into full TCR-CD3 complexes, but a CD3γ mutant with the extracellular domain of CD3δ failed to be incorporated (4, 22, 26).

The persisting uncertainties about the physical nature of TCR-CD3 extracellular domain interactions have resulted in a number of competing models (2). Early models emphasized lateral interactions between Ig domains of TCR and CD3 dimers. However, a more recent model suggested the possibility that the CD3 ectodomains may be located close to the cell membrane underneath the TCR constant domains (27). This model is based on three facts: 1) the TM domains of TCRα-CD3δε and TCRβ-CD3γε are within close proximity (4); 2) the CD3 stalks are substantially shorter than the TCR connecting peptides (2); 3) the location of conserved glycans in CD3γ, CD3δ, and TCRαβ excludes particular surfaces as candidates for such interactions (27). This model suggests that the stalk regions of TCRα-CD3δε and TCRβ-CD3γε may form a three-chain interface. We therefore investigated whether the conserved CXX-CXEXXX motif present in all CD3 chains contributes to assembly of TCR-CD3 complexes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Reagents

Anti-CD3ε (mouse mAb UCHT1) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA), and high affinity anti-hemagglutinin (anti-HA, rat mAb 3F10) and calcium-dependent anti-Protein C (anti-PC, mouse mAb HPC4) were from Roche Applied Science. Streptavidin coupled to agarose beads was purchased from Sigma, and digitonin was from Biosynth International (Naperville, IL).

cDNA Constructs and in Vitro Transcription

Human CD3γ, -δ, -ε, and -ζ constructs were generated form peripheral blood lymphocytes by reverse transcription-PCR, whereas TCRα and -β sequences originated from the A6 T cell clone (28). All sequences were cloned into a modified pSP64 vector (provided by M. Kozak) with the murine H-2Kb signal sequence (4). Mutations were introduced by PCR using overlapping primers. Peptide tags were added as C-terminal in-frame fusions, usually with a three-amino acid flexible linker. The streptavidin-binding peptide (SBP) was sequence C4 (29), with 4 methionines and 1 cysteine changed to serine so that radiolabeled methionine or cysteine would not be incorporated into the tag. Peptide tag sequences (single-letter code) were as follows: SBP (SDEKTTGWRGGHVVEGLAGELEQLRAR-LEHHPQGQREPSSSGGSKLG), PC (EDQVDPRLIDGK), and HA peptide (YPYDVPDYA). In vitro transcription was performed from linearized cDNA constructs using a RiboMax T7 large scale RNA production kit and methyl-7G cap analog (Pro-mega, Madison, WI).

Translation and Assembly Reactions

Each 25-μl reaction contained 17.5 μl of nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega), 0.5 μl of amino acid mixture minus cysteine and methionine (Promega), 0.5 μl of SUPERase-In RNase inhibitor (Ambion), 1.0 μl of 35S-labeled methionine (Amersham Biosciences), equivalent molar amounts of each RNA (60–200 ng of each), and 2.0 μl of ER microsomes. These microsomes were prepared on continuous iodixanol gradients from a mouse IVD12 hybridoma (ATCC) as previously described (4). All translation and assembly reactions were performed at 30 °C. An initial translation period of 30 min under reducing conditions was followed by a 2–4-h assembly period (4 h for complete TCR-CD3 complexes, 2 h for any assembly intermediate) after the addition of GSSG to 4 mM. Reaction volumes were 25–100 μl as required for optimal signal with multistep sequential non-denaturing IP (snIP) procedures.

Immunoprecipitation, Electrophoretic Analysis, and Densitometry

Translation and assembly reactions were stopped by dilution with 1 ml of ice-cold TBS, 10 mM iodoacetamide, and microsomes were pelleted (10 min/20,800 g/4 °C) and rinsed. Pellets were resuspended in 20 μl of solubilization/IP buffer (TBS plus 0.5% digitonin, 10 mM iodoacetamide, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; with 1 mM CaCl2 when anti-Protein C mAb was used) by vigorous pipetting and then rotated for 30 min at 4 °C in a total of 400 μl of solubilization/IP buffer. Lysates were pre-cleared for 1 h with PBS/bovine serum albumin-blocked Sepha-rose 4 beads, and primary captures were performed overnight at 4 °C. Primary IP products were washed twice in 0.5 ml of wash buffer (TBS plus 0.5% digitonin, 10 mM iodoacetamide; with 1 mM CaCl2 for anti-Protein C mAb binding). Nondenaturing elution of SA-captured complexes was performed by incubation with 400 μl of solubilization/IP buffer with 100 μM free biotin for 1 h at 4 °C, and eluted complexes were incubated with subsequent antibodies and Protein G-Sepharose 4 beads (Amersham Biosciences) for 2 h at 4 °C and washed as before. Nondenaturing elution with EDTA (PC tag) was performed as described (4). Final precipitates were digested for 1 h at 37 °C with 500 units of endoglycosidase H (New England Biolabs), separated on 12% BisTris gels under nonreducing conditions (Invitrogen), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and exposed to PhosphorImager plates. Densitometry was performed using the Wide Line tool in the ImageQuant software package (Amersham Biosciences).

Chelation of Cations during TCR-CD3 Assembly

RNAs were translated for 30 min under reducing conditions to permit insertion of newly synthesized radiolabeled proteins into ER microsomes. 20 mM EDTA was then added to the reaction to chelate all divalent cations (0.5 mM Mg2+ is present in rabbit reticulocyte lysate); the same volume of water was added to control reactions. 4 mM GSSG was added simultaneously to initiate formation of structural disulfide bonds. Following a 2–4-h assembly period, membrane microsomes were pelleted and solubilized in IP buffer supplemented with 20 mM EDTA. TCR-CD3 complexes were isolated by one-step IP using the CD3ε-specific UCHT1 mAb. Endoglycosidase H digestion, electrophoresis, and densitometry were performed as described above.

RESULTS

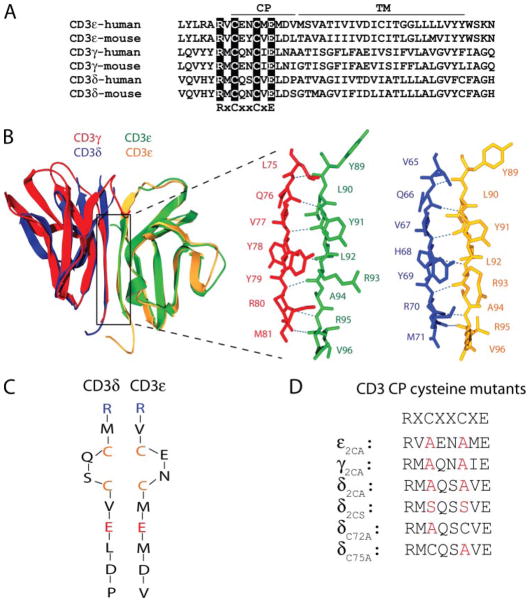

The Membrane-proximal Tetracysteine Motif of CD3γε and CD3δε

The membrane-proximal segments of CD3γ, -δ, and -ε carry a highly conserved CXXCXEXXX sequence motif, and the two cysteines within this motif are located at positions −6 and −9 relative to the predicted TM segments (Fig. 1A). The NMR and crystal structures of CD3γε and CD3δε demonstrated that the G strands of the two chains form a long β-sheet at the dimer interface (27, 30, 31), as illustrated in Fig. 1B for human CD3γε and CD3δε. The cysteines were not included in these recombinant soluble proteins or could not be resolved in these structures, but the available structural information indicates that the four cysteines are located within close proximity in the stalk region of both CD3 dimers. Conserved arginines are located close to the C terminus of the β-strands, and the stalk starts with the first cysteine of this motif (Fig. 1C). The four cysteines may form two intrachain disulfide bonds that stabilize the secondary structure of the CD3 stalk regions or may coordinate a divalent cation, such as zinc. The CD3 constructs that were used to probe the contribution of these cysteine residues to assembly of CD3 dimers with TCR are illustrated in Fig. 1D.

FIGURE 1. A highly conserved membrane-proximal tetracysteine motif in the stalk region of CD3γε and CD3δε dimers.

A, sequence alignment of human and mouse CD3γ, -δ, and -ε sequences in the membrane-proximal extracellular and TM domains. The conserved CXXCXEXXX motif in the connecting peptide (CP) and the conserved arginine at the −2-position relative to this motif are highlighted. B, ribbon diagrams of the crystal structures of human CD3γε and CD3δε extracellular domains overlaid based on the ε chain present in both dimers (Protein Data Bank code 1SY6 and 1XIW, respectively) (27, 30). The parallel β-strands of each subunit that create a β-sheet at the dimer interface are boxed on the left and shown separately for CD3γε (γ, red; ε, green) and CD3δε (δ, blue; ε, yellow) on the right. C, the cysteines comprising the tetracysteine motif are located within close proximity of each other in the stalk region of CD3δε (and CD3γε). The membrane-proximal CD3δ and CD3ε sequences are aligned, starting with the conserved arginine residues at the C-terminal end of the β-strands shown in B. The cysteines do not form interchain disulfide bonds in assembly-competent CD3δε or CD3γε dimers. Rather, they may form intrachain disulfide bonds or coordinately bind a polar ligand. D, mutants used to probe the role of tetracysteine motifs in assembly of CD3 dimers with TCR.

The Four Membrane-proximal Cysteine Residues Are Not Required for CD3δε or CD3γε Dimerization

We examined the assembly of CD3 dimers and their interaction with TCR using an in vitro translation system with ER microsomes isolated from a murine B cell hybridoma, and we and others have previously shown that this system faithfully reproduces protein interactions in the ER identified with metabolic labeling techniques in cells (4, 32, 33). Major advantages of this system are that a series of mutations can be evaluated in parallel under identical reaction conditions and that quantification of 35S-labeled protein complexes provides highly reproducible measurements (25).

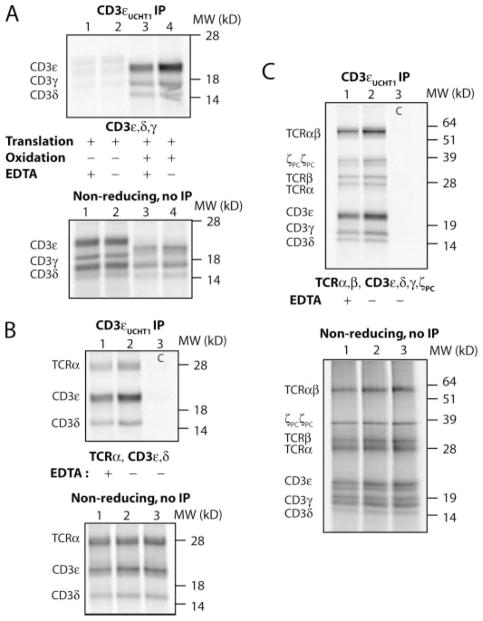

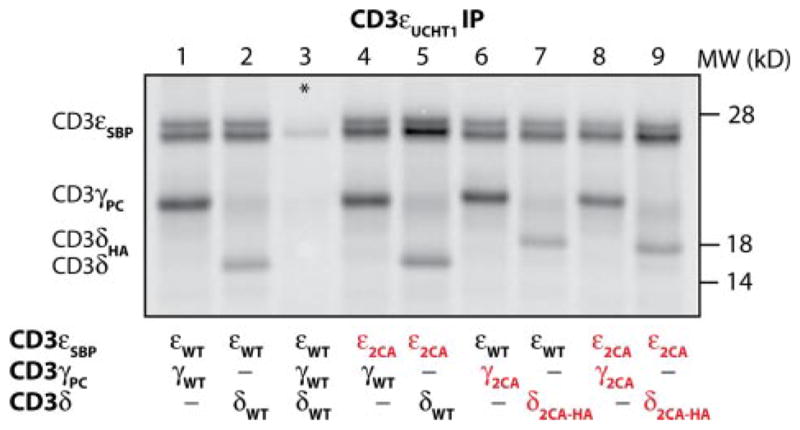

Previous studies based on Western blotting techniques had suggested that the membrane-proximal cysteines may contribute to formation of CD3 dimers (31, 34), and we therefore tested the efficiency of CD3 dimerization for mutants in which both membrane-proximal cysteines of CD3γ, -δ, and/or -ε were substituted by alanine (Fig. 2). CD3 complexes were isolated with the UCHT1 mAb that binds to an exposed surface epitope of CD3ε. This mAb is suitable for this analysis, because it immunoprecipitates properly folded CD3γε and CD3δε dimers (Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 2), including CD3 dimers incorporated into TCR-CD3 complexes (Figs. 3–6) (4, 27, 35, 36). Ala-nine substitution of the two membrane-proximal cysteines of CD3ε (ε2CA) did not reduce recovery of dimers with WT CD3γ or CD3δ (lanes 4 and 5). A mixing control (*, lane 3) in which the three chains were translated separately and then combined prior to solubilization of membranes with digitonin and IP demonstrated that dimer formation occurred in ER micro-somes and not following solubilization. Similar mutations of both cysteines in either CD3γ or CD3δ (γ2CA and δ2CA, respectively, lanes 6 and 7) did not impair dimer formation with WT CD3ε, and even alanine substitution of all four membrane-proximal cysteines did not reduce either CD3γε or CD3δε dimerization (lanes 8 and 9).

FIGURE 2. The membrane-proximal cysteine residues are not required for CD3 dimer formation.

CD3γε and CD3δε dimer formation was examined using an in vitro translation system with ER microsomes using RNAs for CD3γ, CD3δ, and CD3ε WT constructs (lanes 1 and 2) or mutants in which both membrane-proximal cysteines of one chain (lanes 4 –7) or two chains (lanes 8 and 9) were substituted by alanine. The conformation-sensitive UCHT1 mAb specific for CD3ε was used in the IP. In a mixing control (*), CD3γ, -δ, and -ε RNAs were translated separately, and the contents of these reactions were combined prior to detergent solubilization and IP.

FIGURE 3. The membrane-proximal cysteines of CD3δε contribute to assembly with TCRα.

A, CD3ε and CD3δ mutants in which both membrane-proximal cysteines were substituted by alanine (ε2CA and δ2CA, respectively) were analyzed for their ability to assemble into a three-chain TCRα-CD3δε complex. TCRα-CD3 complexes were isolated by two-step snIP using the PC tag attached to TCRα and the CD3ε-specific UCHT1 mAb. The amount of immunoprecipitated TCRα was quantitated relative to the reaction with WT sequences (lane 1). Substitution of the two membrane-proximal cysteines of CD3δ to alanine substantially reduced assembly with TCRα (lane 5), and substitution of all four membrane-proximal cysteines diminished assembly to less than 10% relative to WT (lane 7). Lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8 represent mixing controls (*) in which TCRα and CD3δε RNAs were translated in separate reactions that were combined prior to detergent solubilization of ER membranes. SDS-PAGE of aliquots of reactions prior to IP (lower panel) demonstrated equal quantities of input proteins. B, analysis of CD3δ mutants. CD3δ mutants were analyzed for their ability to form CD3δε dimers (lanes 1–5) and to assemble into TCRα-CD3δε complexes (lanes 6 –10). The two membrane-proximal cysteines were either both substituted by alanine (δ2CA, lanes 2 and 7) or serine (δ2CS, lanes 5 and 10) or individually substituted by alanine (δC72A and δC75A, lanes 3, 4, 8, and 9). CD3δε dimer formation was assessed by two-step snIP targeting the SBP tag on CD3ε and the HA tag on CD3δ (lanes 1–5), whereas TCRα-CD3δε complexes were isolated using the PC tag attached to TCRα and the CD3ε specific UCHT1 mAb (lanes 6–10). Even conservative substitution of the two CD3δε cysteines by serine substantially reduced assembly with TCRα (lane 10) but did not affect CD3δε dimerization (lane 5). Mutation of single membrane-proximal cysteines resulted in formation of covalent CD3δε dimers (†, lanes 3 and 4), indicating that the cysteines comprising the tetracysteine motif are within close proximity. Analysis of aliquots of translation reactions prior to IP demonstrated equal quantities of input proteins (lower panel).

FIGURE 6. Chelation of divalent cations does not interfere with assembly of complete TCR-CD3 complexes.

A, a control experiment confirmed that CD3 dimers do not form under the reducing conditions of the initial translation period. Following this translation period of 30 min, reactions in lanes 3 and 4 were oxidized by the addition of oxidized glutathione. CD3 dimers were immunoprecipitated using the UCTH1 mAb after a 2-h assembly period. B, the addition of EDTA does not prevent assembly of TCRαwith CD3δε. Three-chain complexes were isolated with the UCHT1 mAb even when EDTA was added before the 2-h assembly period. Lane 3 represents an IP specificity control (C) with an isotype control antibody. C, the presence of EDTA does not interfere with formation of complete TCR-CD3 complexes. Specificity of IP was demonstrated by replacing the CD3ε-specific UCHT1 mAb (lanes 1 and 2) with an isotype control mAb (lane 3).

Mutation of Membrane-proximal Cysteines Substantially Impairs Assembly of CD3δε with TCRα

The first major step in the assembly of TCR-CD3 complexes is the interaction of TCRα with the CD3δε dimer (4, 20), and we examined if mutation of the membrane-proximal cysteines of CD3δ or -ε affects this assembly step (Fig. 3). Three-chain complexes were isolated by two-step snIP using the calcium-dependent PC epitope tag attached to TCRα in the first IP step. Following elution with EDTA, complexes containing CD3ε were then isolated in the second IP step with the UCHT1 mAb. Substitution of the two cysteines at positions 72 and 75 of CD3δ substantially reduced assembly of CD3δε with TCRα (24% relative to WT; lane 5), and simultaneous substitution of all four membrane-proximal cysteines of the CD3δε dimer resulted in an almost complete assembly defect (5% relative to WT; lane 7). Substitution of the two cysteines in only CD3ε had only a subtle effect (lane 3), but these two cysteines contributed to assembly, because simultaneous mutation of CD3δ and CD3ε resulted in a substantially more severe assembly defect than mutation of CD3δ alone (5% versus 24% relative to WT, respectively). Mixing controls (*, lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) demonstrated specificity of assembly, and parallel analysis of aliquots of reactions without IP (lower panel) confirmed the presence of equal quantities of input proteins.

Based on these results, we generated mutants in which the cysteines were individually substituted by alanine (δC72A and δC75A) and examined CD3δε dimerization as well as assembly with TCRα (Fig. 3B). Both point mutations reduced assembly with TCRα to a similar extent as simultaneous substitution of both cysteines (23–30% relative to WT; lanes 8 and 9). Loss of either one or both cysteine side chains may prevent formation of an intrachain disulfide bond and thus modify the conformation of the stalk region. We also generated a CD3δ mutant in which both cysteines were substituted by serine (δ2CS); this mutant maintained the polar character and size of the side chains at positions 72 and 75 but lacked the ability to form a disulfide bond at this site. This mutant showed the same assembly defect as the single or double alanine mutants (lane 10).

Analysis of CD3δ mutants in which only a single cysteine was modified also demonstrated that the four cysteines in the stalk region were within close proximity; mutation of either cysteine resulted in the formation of covalent dimers with CD3ε (indicated by the dagger in Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4). The IP strategy used for this experiment ensured isolation of CD3 heterodimers, because the streptavidin-binding peptide (SBP) tag attached to CD3ε was used in the first IP step (elution with biotin), and the HA tag on CD3δ was used in the second step.

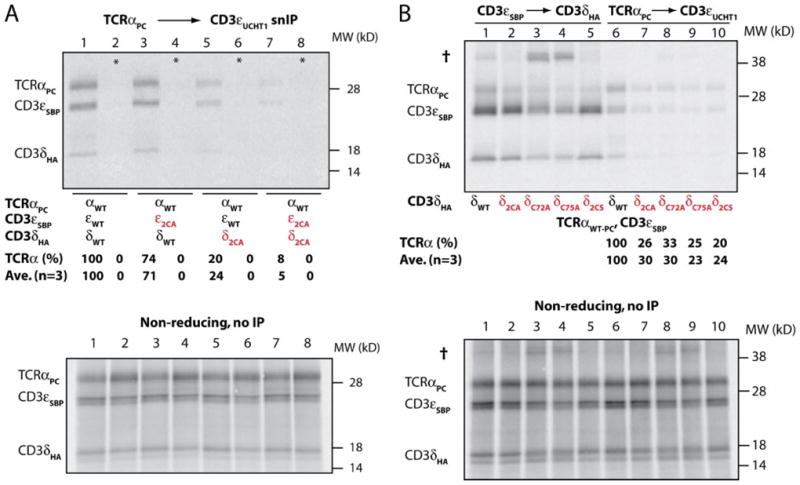

A TCRα Mutant Lacking the Entire Ig Domain Assembles with CD3δε

These results suggested that interactions among the membrane-proximal segments may be involved in assembly of TCRα with CD3δε. We examined the structural requirements on the TCRα side by generating a mutant that contained the entire connecting peptide but lacked both variable and constant Ig domains (αTM2) (Fig. 4A). This mutant assembled with CD3δε (Fig. 4B, lane 3), indicating that interaction among TCR Ig domains and CD3δε was not required for this step. Densitometry measurements of input radiolabeled proteins (Fig. 4B, lower panel) demonstrated that similar molar quantities of WT TCRα and αTM2 proteins were present in these reactions (lanes 1 and 3, respectively). Another mutant in which the TCRα connecting peptide was shortened to six residues (αTM1) also bound to CD3δε, but the yield of this three-chain complex was reduced (lane 2, 30% relative to WT).

FIGURE 4. A TCRα mutant lacking both Ig domains assembles with CD3δε.

A, TCRα assembly with the CD3δε dimer was compared for full-length TCRα, a mutant lacking the two TCRα Ig domains (αTM2), and a mutant in which the connecting peptide was shortened to six residues (αTM1). B, complexes containing these TCRα constructs and CD3δε were isolated by two-step snIP using the SBP tag on TCRα and the CD3ε-specific UCHT1 mAb. The αTM2 construct lacking both TCRα Ig domains assembled with CD3δε; assembly occurred at reduced levels with the shorter αTM1 construct. The αTM1 peptide was targeted in the first IP step and was therefore present in the isolated complex, but this short peptide was difficult to visualize at the quantities isolated in this IP (lane 2). Signal peptide cleavage of αTM2 protein was incomplete (†, lane 3 of the no IP gel in the lower panel). The mixing control in lane 4 (*) in which TCRα and CD3δε chains were translated separately and mixed prior to detergent solubilization demonstrated specificity of assembly. C, CD3δ cysteine mutants yield similar results with the TCRα mutants as with WT TCRα. Three-chain assembly reactions were set up with CD3δ, CD3ε, and SBP-tagged TCR αTM1 or αTM2 peptides, and three-chain complexes were isolated as in B. Substitution of one or both cysteine residues by alanine (δC72A, δC75A, and δ2CA, respectively) or serine (δ2CS) substantially reduced assembly of either TCR αTM1 or αTM2 with CD3δε. The amount of immunoprecipitated CD3ε in reactions with these CD3δ mutants was compared with reactions with WT CD3δ.

Both TCRα mutants showed a pattern comparable with WT TCRα when analyzed against the panel of CD3δ mutants in which the membrane-proximal cysteines were substituted by alanine or serine (Figs. 3B and 4C). For example, the double serine CD3δ mutant (δ2CS) showed a severe assembly defect with both αTM1 and αTM2 proteins (7–10% relative to WT CD3δ), indicating that loss of the TCRα Ig domains had not resulted in a different type of interaction with CD3δε for these proteins.

Mutation of Membrane-proximal Cysteines Also Affects Association of CD3γε with TCR but Not Association of the ζζ Dimer

The CD3γε dimer assembles efficiently with TCRαβ only in the presence of the CD3δε dimer (4), indicating that association of CD3γε usually occurs following formation of the TCR-CD3δε assembly intermediate. We therefore assessed the effect of mutation of the membrane-proximal cysteines in the CD3γε dimer in the context of the six-chain CD3δε-TCRαβ-CD3γε assembly intermediate by targeting the CD3γ (PC tag) and CD3δ (HA tag) chains in a two-step snIP (Fig. 5A). We have previously shown that this IP method yields stoichiometric quantities of all three dimers (1:1:1) (25). Mutation of the two cysteines in either CD3γ or CD3ε (γ2CA and ε2CA) moderately reduced recovery of the six-chain complex (lanes 3 and 5), but substitution of all four cysteines resulted in a severe assembly defect (lane 7, 11% relative to WT). In this experiment, the CD3ε mutation affected the interaction of both CD3δε and CD3γε with TCR, but the results in Fig. 3A had demonstrated that the CD3ε mutation had only a modest effect in the context of the CD3δε dimer as long as CD3δ was WT (71% of CD3δε-TCRα complexes relative to WT CD3ε). The observed reduction in the yield of six-chain complexes was thus primarily due to mutation of the four cysteines in the CD3γε dimer. The results for the CD3γε dimer were thus similar to CD3δε, because mutation of all four cysteines had a more substantial effect than mutation of cysteines in only one chain (Figs. 3A and 5A). Mutation of the membrane-proximal cysteines of CD3γ and -ε did not affect the last assembly step, the association of the ζζ dimer (Fig. 5B), because the reduction in recovery of fully assembled complexes resembled the reduction of six-chain complexes, indicating that there was no additional negative effect on the last assembly step. In fact, the yield of complexes with the CD3γ and -ε cysteine mutations was higher in the presence of ζζ (lane 6, 57% of complexes relative to WT CD3γ and -ε) than in its absence (lane 3, 15% of complexes relative to WT), suggesting that the ζζ dimer may stabilize complexes that incorporate these mutated CD3 chains.

FIGURE 5. Role of tetracysteine motifs in formation of the six-chain CD3δε-TCRαβ-CD3γε intermediate.

A, assembly of the six-chain complex was examined in reactions with TCRα, TCRβ, and CD3γ, -δ, and -ε. TCR complexes containing both CD3γε and CD3δε were isolated by two-step snIP utilizing the PC and HA tags attached to CD3γ and CD3δ, respectively. The other components (TCRα, TCRβ, and CD3ε) carried SBP tags to facilitate resolution of all components by SDS-PAGE. Substitution of the two membrane-proximal cysteines by alanine in only CD3γ (γ2CA) or CD3ε (ε2CA) moderately reduced assembly of the six-chain complex, but introduction of these mutations into both CD3γ and CD3ε chains (γ2CA and ε2CA) resulted in a severe assembly defect. B, the cysteine mutations do not affect the final assembly step, association of the ζζ dimer. Assembly reactions with all TCR-CD3 components (lanes 4 – 6) were compared with reactions lacking the ζ chain (lanes 1–3). Complete TCR-CD3 complexes were isolated by two-step snIP targeting the ζ chain (PC tag) and CD3ε (UCHT1 mAb) (lanes 4 – 6), whereas six-chain complexes were isolated from reactions lacking the ζ chain by two-step snIP targeting CD3δ (PC tag) and CD3γ (HA tag) (lanes 1–3).

Chelation of Divalent Cations Does Not Affect the Efficiency of TCR-CD3 Assembly

Clusters of cysteine residues can coordinate zinc or other cations (37), and we therefore examined the requirement for divalent cations during assembly of TCR-CD3 complexes as an alternative hypothesis to the formation of intrachain disulfide bonds described above. Once a divalent cation is buried at a protein-protein interface, dissociation may be very slow and occur only following dissociation of the complex. We therefore chose an experimental design in which divalent cations were chelated by EDTA prior to initiation of assembly. In the in vitro translation system, initial translation occurs under reducing conditions, and the reaction is shifted to mildly oxidizing conditions following insertion of radiolabeled proteins into ER microsomes to enable formation of structural disulfide bonds. All dimers that assemble into TCR-CD3 complexes require formation of structural disulfide bonds, and assembly thus does not occur under the reducing conditions of the initial translation period. A control experiment (Fig. 6A) confirmed that no CD3 dimers were formed during the initial translation period (lanes 1 and 2) and that the presence of EDTA had little effect on the subsequent formation of CD3 dimers (lanes 3 and 4). We added a large molar excess of EDTA (20 mM) following completion of the translation period and assessed whether the presence of EDTA during assembly would reduce the yield of TCRα-CD3δε three-chain complexes (Fig. 6B) or full TCR-CD3 complexes (Fig. 6C). The results clearly demonstrated that chelation of divalent cations had no substantial effect on assembly, ruling out the possibility that the membrane-proximal tetracysteine motifs bind a divalent cation essential for interaction of CD3 dimers with TCR. A small reduction in recovery of the assembled complex was observed, most likely due to the fact that the presence of divalent cations promotes oxidative disulfide bond formation.

DISCUSSION

These results demonstrate that the tetracysteine motif in the membrane-proximal stalk regions of CD3γε and CD3δε dimers is an important structural element for their assembly with TCR. Assembly was severely impaired (to ~10% or less compared with WT) when all four cysteines of a given CD3 dimer were mutated to alanine. The interaction of CD3δε with TCRα was examined in detail, and mutation of the two membrane-proximal cysteines of CD3δ to alanine or serine was found to substantially reduce assembly (to 23–30%). Mutation of the two cysteines of CD3ε only moderately affected interaction with TCRα, but simultaneous mutation of CD3δ and CD3ε resulted in an assembly defect (reduction to ~5%) considerably more severe than for the CD3δ mutant alone. Similarly, mutation of the two membrane-proximal cysteines of CD3γ moderately reduced assembly with TCR (to 46%), but combined CD3γ and CD3ε mutations again resulted in a severe assembly defect (to 11%). In this experiment, the CD3ε mutant was incorporated into both CD3γε and CD3δε dimers, but it appeared that the assembly defect was primarily localized to the CD3γε side, because the CD3ε mutation alone only moderately affected the CD3δε-TCRα interaction. These are the first point mutations in the CD3 extracellular domains shown to significantly impact assembly of CD3 dimers with TCR.

Previous studies had suggested that the CXXC motifs contribute to CD3 dimer formation. Borroto et al. (34) transfected COS cells with human CD3 constructs in which the cysteines in the CXXC motif of CD3ε were mutated to alanine. CD3ε chains were immunoprecipitated with the APA1/1 mAb and associated CD3γ or CD3δ were visualized by Western blotting (34). Sun et al. (31) also transfected COS cells but performed immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis with antibodies to attached HA and FLAG epitope tags. These authors mutated the cysteines of murine CD3ε to serine but did not observe a substantial reduction in the efficiency of assembly with CD3γ (67% of WT), in contrast to the results reported by Borroto et al. (34) with a CD3ε alanine mutant. However, introduction of three additional mutations (at Tyr59, Tyr72, and Tyr74) located N-terminal to Cys80 and Cys83 of CD3ε severely impaired CD3γε dimer formation (31). We performed a comprehensive analysis in which the CXXC motif was mutated in all three CD3 chains and found that even mutation of all four membrane-proximal cysteines did not reduce CD3γε or CD3δε dimer formation. The cysteine residues thus do not appear to be required for CD3 dimerization, unless the dimer interface is weakened by introduction of several other mutations. This conclusion is consistent with the finding that CD3γε and CD3δε can be refolded from proteins expressed in Escherichia coli that lack the CXXC motifs (30, 31).

Our mutagenesis experiments also demonstrate that the cysteines can form covalent CD3δε dimers when a single cysteine in the CXXC motif is mutated to alanine (Fig. 3B). The cysteines of CD3δ and CD3ε chains are thus within sufficient proximity to form an interchain disulfide bond, and the absence of such interchain disulfide bonds in properly folded CD3γε and CD3δε dimers indicates that the SH groups are either stably bound to an unknown polar ligand or that they have already formed stable intrachain disulfide bonds prior to CD3 dimerization.

We considered the possibility that the tetracysteine motif may coordinate a cation such as zinc. Cysteine-based motifs coordinate zinc and other cations in many different proteins, such as the DNA binding domain of the glucocorticoid receptor. The glucocorticoid receptor DNA binding domain has two zinc-containing regions, and each binds zinc through four cysteine residues. The first zinc binding site is formed by two CXXC motifs, and the bound zinc ion stabilizes the α-helix that binds in the major groove of double-stranded DNA (37, 38). However, assembly of the CD3δε-TCRα intermediate or complete TCR-CD3 complexes was not reduced when cations were chelated with EDTA. The mutagenesis experiments also argue against an essential role of a coordinated cation in assembly of CD3 dimers with TCR. Mutation of the two cysteines in one chain of a CD3 dimer would be predicted to destroy a metal coordination site, yet mutation of the CXXC motif in CD3ε alone only modestly reduced assembly of CD3δε with TCRα.

An alternative explanation for the important structural role of the CXXC motifs is that the two membrane-proximal cysteines of a given CD3 chain form an intrachain disulfide bond, as previously suggested by Borroto et al. (34). Several lines of evidence support this hypothesis. The close physical proximity of the two cysteines may favor rapid formation of intrachain disulfide bonds upon insertion of the nascent protein chain into the oxidizing environment of the ER, and formation of these disulfide bonds may occur more rapidly than folding of the Ig domain and subsequent CD3 dimerization. Rapid formation of an intrachain disulfide bond may thus explain why properly folded CD3γε or CD3δε dimers lack interchain disulfide bonds. CXXC motifs form the catalytic site of thioredoxin and related enzymes, and the two cysteines form a disulfide bond at a particular step in the catalytic cycle, indicating that cysteines in CXXC motifs can be within sufficient proximity for disulfide bond formation. The N-terminal cysteine in the CXXC motif of thioredoxin serves as a nucleophilic attacking group and forms a transient disulfide bond with the substrate protein. Subsequent attack of this disulfide by the C-terminal cysteine releases the reduced product and results in the formation of a disulfide bond between the two cysteines of the CXXC motif (39, 40).

We made substantial efforts to isolate the membrane-proximal domains for analysis by mass spectrometry to directly demonstrate the presence of intrachain disulfide bonds (the presence of the disulfide bond is predicted to reduce the molecular mass of the peptide by 2 daltons). However, despite the use of multiple enzymes and isolation techniques, membrane-proximal or TM domain cleavage fragments could not be identified by mass spectrometry, although many other fragments were identified at high redundancy. Proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-proximal fragment may be impaired by the neighboring TM domain, and recovery of long fragments containing the TM may be reduced by their hydrophobicity and/or bound detergent. Nevertheless, all available data are consistent with the hypothesis that the four membrane-proximal cysteines serve a structural role by forming two intrachain disulfide bonds in the CD3 stalk regions.

Much effort in the field has focused on identifying contacts between the Ig domains of CD3 dimers and TCR (2), but point mutations that substantially impair assembly had not been identified. This study demonstrates that the stalk regions of the CD3 dimers are important structural elements for the interaction of CD3 dimers with TCR. This conclusion is also supported by the finding that a TCRα mutant containing the entire connecting peptide but lacking the Ig domains assembled with CD3δε, whereas a mutant in which the connecting peptide was shortened to six residues assembled at a reduced level. A structural role of the CD3 stalk region CXXC motifs in assembly is also consistent with the reported finding that mutations in the TCRα connecting peptide impair TCR signaling (41). The membrane-proximal CXXC motifs may contribute to the secondary structure of the CD3 stalk regions and may also help to properly position the CD3 TM domains for interaction with the appropriate TCR TM helix.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 AI054520 (to K. W. W.).

The abbreviations used are: TCR, T cell receptor; TM, transmembrane; SBP, streptavidin-binding peptide; PC, Protein C-derived peptide; HA, hemag-glutinin peptide; IP, immunoprecipitation; snIP, sequential nondenaturing immunoprecipitation; TBS, Tris-buffered saline; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; WT, wild type; mAb, monoclonal antibody; BisTris, 2-[bis(2-hydroxye-thyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

References

- 1.Oettgen HC, Terhorst C. Crit Rev Immunol. 1987;7:131–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhns MS, Davis MM, Garcia KC. Immunity. 2006;24:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samelson LE, Harford JB, Klausner RD. Cell. 1985;43:223–231. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Call ME, Pyrdol J, Wiedmann M, Wucherpfennig KW. Cell. 2002;111:967–979. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01194-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Punt JA, Roberts JL, Kearse KP, Singer A. J Exp Med. 1994;180:587–593. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashwell JD, Klausner RD. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:139–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumberg RS, Alarcon B, Sancho J, McDermott FV, Lopez P, Breitmeyer J, Terhorst C. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14036–14043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumberg RS, Ley S, Sancho J, Lonberg N, Lacy E, McDermott F, Schad V, Greenstein JL, Terhorst C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7220–7224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de la Hera A, Muller U, Olsson C, Isaaz S, Tunnacliffe A. J Exp Med. 1991;173:7–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Exley M, Terhorst C, Wileman T. Semin Immunol. 1991;3:283–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weissman AM, Frank SJ, Orloff DG, Mercep M, Ashwell JD, Klausner RD. EMBO J. 1989;8:3651–3656. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sussman JJ, Bonifacino JS, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Weissman AM, Saito T, Klausner RD, Ashwell JD. Cell. 1988;52:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90533-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weissman AM, Baniyash M, Hou D, Samelson LE, Burgess WH, Klausner RD. Science. 1988;239:1018–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.3278377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krissansen GW, Owen MJ, Fink PJ, Crumpton MJ. J Immunol. 1987;138:3513–3518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krissansen GW, Owen MJ, Verbi W, Crumpton MJ. EMBO J. 1986;5:1799–1808. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van den Elsen P, Shepley BA, Borst J, Coligan JE, Markham AF, Orkin S, Terhorst C. Nature. 1984;312:413–418. doi: 10.1038/312413a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold DP, Puck JM, Pettey CL, Cho M, Coligan J, Woody JN, Terhorst C. Nature. 1986;321:431–434. doi: 10.1038/321431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold DP, Clevers H, Alarcon B, Dunlap S, Novotny J, Williams AF, Terhorst C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7649–7653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alcover A, Mariuzza RA, Ermonval M, Acuto O. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4131–4135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kearse KP, Roberts JL, Singer A. Immunity. 1995;2:391–399. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenner MB, Trowbridge IS, Strominger JL. Cell. 1985;40:183–190. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dietrich J, Neisig A, Hou X, Wegener AM, Gajhede M, Geisler C. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:299–310. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghendler Y, Smolyar A, Chang HC, Reinherz EL. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1529–1536. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geisler C. J Immunol. 1992;148:2437–2445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Call ME, Pyrdol J, Wucherpfennig KW. EMBO J. 2004;23:2348–2357. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wegener AM, Hou X, Dietrich J, Geisler C. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4675–4680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnett KL, Harrison SC, Wiley DC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16268–16273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407359101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garboczi DN, Ghosh P, Utz U, Fan QR, Biddison WE, Wiley DC. Nature. 1996;384:134–141. doi: 10.1038/384134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson DS, Keefe AD, Szostak JW. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3750–3755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061028198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kjer-Nielsen L, Dunstone MA, Kostenko L, Ely LK, Beddoe T, Mifsud NA, Purcell AW, Brooks AG, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7675–7680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402295101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun ZJ, Kim KS, Wagner G, Reinherz EL. Cell. 2001;105:913–923. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huppa JB, Ploegh HL. J Exp Med. 1997;186:393–403. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ribaudo RK, Margulies DH. J Immunol. 1992;149:2935–2944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borroto A, Mallabiabarrena A, Albar JP, Martinez AC, Alarcon B. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12807–12816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burns GF, Boyd AW, Beverley PC. J Immunol. 1982;129:1451–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borst J, Prendiville MA, Terhorst C. Eur J Immunol. 1983;13:576–580. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830130712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hard T, Kellenbach E, Boelens R, Maler BA, Dahlman K, Freedman LP, Carlstedt-Duke J, Yamamoto KR, Gustafsson JA, Kaptein R. Science. 1990;249:157–160. doi: 10.1126/science.2115209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luisi BF, Xu WX, Otwinowski Z, Freedman LP, Yamamoto KR, Sigler PB. Nature. 1991;352:497–505. doi: 10.1038/352497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritz D, Beckwith J. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:21–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powis G, Montfort WR. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2001;30:421–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Backstrom BT, Milia E, Peter A, Jaureguiberry B, Baldari CT, Palmer E. Immunity. 1996;5:437–447. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]