Abstract

Setting

Massachusetts General Hospital embarked on a 4-year project to reduce readmissions in a high volume general medicine unit (November 2009 to September 2013).

Objective

To reduce 30-day readmissions to 10% through improved care coordination.

Design

As a before–after study, a total of 7586 patients admitted to the medicine unit during the intervention period included 2620 inpatients meeting high risk for readmission criteria. Of those, 2620 patients received nursing interventions and 539 patients received pharmacy interventions.

Intervention

The introduction of a Discharge Nurse (D/C RN) for patient/family coaching and a Transitional Care Pharmacist (TC PharmD) for predischarge medication reconciliation and postdischarge patient phone calls. Other interventions included modifications to multidisciplinary care rounds and electronic medication reconciliation.

Main outcome measure

All-cause 30-day readmission rates.

Results

Readmission rates decreased by 30% (21% preintervention to 14.5% postintervention) (p<0.05). From July 2010 to December 2011, rates of readmission among high-risk patients who received the D/C RN intervention with or without the TC PharmD medication reconciliation/education intervention decreased to 15.9% (p=0.59). From January to June 2010, rates of readmission among high-risk patients who received the TC PharmD postdischarge calls decreased to 12.9% (p=0.55). From June 2010 to December 2011, readmission rates for patients on the medical unit that did not receive the designated D/C RN or TC PharmD interventions decreased to 15.8% (p=0.61) and 16.2% (0.31), respectively.

Conclusions

A multidisciplinary approach to improving care coordination reduced avoidable readmissions both among those who received interventions and those who did not. This further demonstrated the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration.

Keywords: Delivery, Reverse Innovations, Diagnostics

Introduction

Hospital readmissions numbered 2.3 million (19%) among Medicare enrolees within 30 days of a previous discharge, generating over $17 billion in healthcare costs in 2004.1 Up to $12 billion of these costs (70%) have been attributed to preventable rehospitalisations.1 With over 13 million hospitalisations driving $102 billion in healthcare costs in 2004, rates of rehospitalisation have become a measure of keen interest.2 In this era of healthcare reform, with increasing emphasis on higher quality healthcare at lower costs, the importance of care coordination during and after hospitalisation has been magnified.

Efforts to improve clinical management and reduce overall utilisation of healthcare have become a nearly universal initiative as the dictums of the Affordable Care Act become a reality. The goal of reducing hospital readmissions within 30 days of a previous discharge is a metric that has captured the attention of healthcare administrators, policymakers and providers. Factors driving readmission rates appear to be complex. Current data suggest that only 50% of the 2.3 million Medicare enrolees readmitted within 30 days in 2004 were seen by primary care providers in the interim and only 38% of heart failure patients are seen within 1 week of discharge.1 3 While a reasonable goal for an index margin of reduction remains undefined, a number of interventions focused on the risk predictive tools, discharge planning and postdischarge care have been introduced.4 Although many interventions demonstrate limited effect,3 there is evidence that educational tools and coordination of timely postdischarge care for patients can effectively reduce readmission rates.5–7

The STate Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) programme was launched by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) with funding from the Commonwealth Fund in May 2009. The primary goal of this collaboration was to share best practices to improve transitions in care and reduce hospital readmissions. Twenty sites were identified in Massachusetts and this grew to 80 sites across multiple states by August 2013. At Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), the STAAR initiative (October 2009 to September 2013) included three inpatient care units. This discussion will focus on the changes on one particular high-volume general medical unit averaging 180 monthly admissions. This quality improvement initiative looked to answer the questions of whether nursing and pharmacy interventions can improve care delivery in high-risk populations, and reduce hospital readmissions in a busy medical unit.

Methods

Owing to the non-invasive nature of implementing nursing and pharmacy interventions, no ethical issues were identified. Minimal concerns were raised regarding privacy or protection of participants. There were no identified potential author conflicts of interest.

Given the volume of patient care occurring in the identified unit, this setting was chosen as a potentially beneficial place for a quality improvement effort. Prior to initiation, the expectation was that readmission rates would decrease and the overall quality of care would improve.

Study design

This was a before–after study to determine the impact of D/C RN and Transitional Care Pharmacist (TC PharmD) interventions on readmission rates among patients at increased risk for readmission. The design rationale was based on the IHI recommended Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles with iterative episodes of change. Readmission rates were tracked in statistical process control charts during the study as were the participants in the study along with their primary reason for hospitalisation.

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria were constructed using two domains (table 1): (1) criteria established in Project Red8 and (2) most common admission diagnoses associated with unit-specific readmissions. All patients admitted to the unit during the project interval (September 2009 to October 2013) who met criteria were categorised as high risk for readmission and identified for interventions. Minor changes to the eligibility criteria occurred during the project using the PDSA cycles. Patient characteristics are listed in table 2.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Pneumonia | <60 years old |

| Atrial fibrillation | Non-English speaking |

| Altered mental status | Left against medical advice |

| Dehydration | Transferred to the ICU |

| Acute renal failure | |

| Urinary tract infection | |

| Cancer pain | |

| >10 Medications |

ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Intervention patients | Non-intervention patients | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean in years) | 72.5 | 51 | <0.01 |

| Women (n, %) | 1152 (0.44) | 2983 (0.51) | <0.01 |

| Heart failure (n, %) | 419 (0.16) | 578 (0.1) | <0.01 |

| Pneumonia (n, %) | 393 (0.15) | 645 (0.13) | <0.01 |

| Atrial fibrillation (n, %) | 340 (0.13) | 446 (0.09) | <0.01 |

| Altered mental status (n, %) | 314 (0.12 | 794 (0.16) | <0.01 |

| Dehydration (n, %) | 314 (0.12) | 844 (0.17) | <0.01 |

| Acute renal failure (n, %) | 209 (0.08) | 695 (0.14) | <0.01 |

| Urinary tract infection (n, %) | 209 (0.08) | 297 (0.06) | <0.01 |

| Cancer pain (n, %) | 131 (0.05) | 99 (0.02) | <0.01 |

| >10 Medications (n, %) | 288 (0.11) | NA | NA |

NA, not applicable.

Sample size

Assuming an initial event rate of 21% for the primary outcome and an α error of 0.05, a pool of approximately 983 patients was estimated to provide 85% power to detect a 30% reduction within a 2.5% margin of error. The initiative continued throughout the entire 4-year time period to optimise results. There were 2620 patients admitted to the unit who met high risk for readmission criteria. Of these, all 2620 patients received nursing interventions and 539 received pharmacy interventions.

Statistical methods

Statistical process control charts were used to track readmission rates. The χ2 testing was used to differentiate rates of readmission for intervention and non-intervention groups. A p value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Intervention

Nursing intervention

Patients were classified on admission by the D/C RN as high risk for readmission according to pre-established inclusion criteria initially adapted from Project Red.8 These criteria were extended to include common admission diagnoses specific to readmissions to the medicine unit (table 1). Patients meeting criteria were identified by the D/C RN by adding an icon to the unit census board, which identified high-risk patients for the multidisciplinary care team. Daily, the D/C RN and the assigned staff nurse assisted patients in establishing a goal for the day, which was written on the patient's bedside board. The D/C RN provided education to each high-risk patient as well as a folder customised to include important information about their care team, follow-up appointments, treatment plan and individualised education materials. Within the folders, there was a place for the patient, or appropriate learner, to write questions for the care team, which were addressed by the D/C RN the following day.

The D/C RN role included care coordination for all patients in the unit and not just those deemed as high risk. The D/C RN facilitated morning multidisciplinary rounds as well as coordinating daily afternoon huddles with senior house staff and the resource nurse to update the plan of care, and creating consensus regarding the anticipated day of patient discharge. Once a date was identified, this date was posted on the unit census board, and was updated twice daily to facilitate early discharges for the next day. The D/C RN assisted staff with arranging simple postdischarge services and collaborated with case management on more complex postdischarge planning.

Pharmacy intervention I: postdischarge calls

During the project, two pharmacy interventions were piloted. The first intervention was a stand-alone postdischarge call programme that was piloted during the first 6 months of the STAAR initiative. The purpose was to provide medication reconciliation and counselling after a patient was discharged home. After receiving notification of a discharge, the TC PharmD would review the patient medication profile and contact patients within 72 h to reconcile their home meds, provide counselling on new medications and to address adherence issues. The call was then documented and primary physicians were notified of any urgent issues. The pharmacy calls continued from January 2010 to June 2010, at which point findings were shared within the institution. As a result, primary care practices began calling patients postdischarge.

Pharmacy intervention II: medication reconciliation and patient education

The second pharmacy intervention occurred during hospitalisation and became the focus of the TC PharmD role. The TC PharmD anticipated medication-related changes for patients classified as high-risk for readmission. Partnering closely with the D/C RN, case managers and care team, the TC PharmD worked to resolve any medication-related issues over the course of the admission and confirm patient understanding of their new medication regimen. On the day of discharge, the TC PharmD completed medication reconciliation, provided counselling and addressed patient adherence barriers including facilitating the filling of discharge prescriptions or assisting with prior authorisations.

Other interventions

Multidisciplinary rounds were modified during this intervention. To assist with establishing the plan for the day, the timing of multidisciplinary rounds was moved and the focus was changed to include barriers to discharge as well as an estimated date of discharge.

The electronic application for physicians to complete medication reconciliation was also updated to identify medication errors and provide additional safeguards during patient discharge.

Outcomes

The outcome measure was all-cause rates of readmission within 30 days. Secondary benefits were identified as a result of this project, but were not measured. All outcomes were tracked by the operations department staff who were blinded to intervention status.

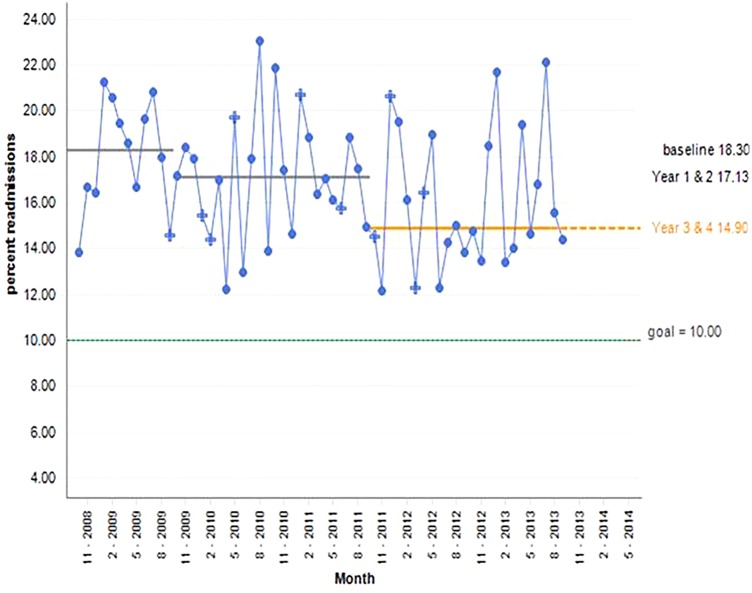

From October 2009 to September 2013, overall readmission rates decreased by 30% from 21% (18% average) preintervention to 14.5% (14.9% average) postintervention (p<0.05; figure 1). From July 2010 to December 2011, rates of readmission among high-risk patients receiving the D/C RN intervention with or without the TC PharmD intervention decreased to 15.9% (p=0.59). From January 2010 to June 2010, rates of readmission among high-risk patients receiving the TC PharmD postdischarge calls decreased to 12.9% (p=0.55). Postdischarge TC PharmD calls demonstrated that 52% of patients deviated from medication instructions after leaving the hospital (table 3). Deviation from medication instructions included patient continuation of medications that had been discontinued during the hospitalisation, patient continuation of over the counter medications (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, etc) that were not mentioned during the previous hospitalisation and patient challenges following proper dosing instructions for medications that were initiated or changed on discharge. From July 2010 through December 2011, readmission rates for patients on the medical unit who did not receive the designated D/C RN or TC PharmD interventions decreased to 15.8% (p=0.61) and 16.2% (0.31), respectively. Patient characteristics in intervention and non-intervention groups are listed in table 2. Inpatient discharge experience satisfaction did not change during this study.

Figure 1.

All-cause 30-day readmissions.

Table 3.

Transitional Care Pharmacists (TC PharmD) postdischarge calls to patients 11 January to 30 June 2010

| Readmissions | Discharges | Readmission rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients called by TC PharmD | 13 | 101 | 12.9 |

| Patients not called by TC PharmD | 91 | 528 | 17.2 |

| Total | 104 | 629 | NA |

NA, not applicable.

Discussion

The STAAR initiative reduced hospital readmissions by 30% in this general medicine unit during the study period, including patients who received discharge interventions as well as those who did not. The D/C RN and TC PharmD interventions targeting high-risk populations alone did not appear to produce statistically significant changes in readmission rates. Additional impact was realised with the changes made to the care team structure, which affected all unit patients. Targeted interventions along with improved hospital coordination can augment processes of care for patients during and after admission. Implementation of similar interventions with improved care coordination may be an effective means of reducing readmissions in other hospitals.

Prior studies examining the impact of patient education-focused nursing interventions have demonstrated to effectively reduce readmissions in several different settings. Coleman et al9 reported reduced readmission rates with the addition of a nurse coordinator and care transition coach at the time of discharge. Jack et al demonstrated the effects of instituting nursing interventions to improve care transitions and reduce readmissions. Connections of readmission rates to patient health literacy have been described by Cloonan et al.10 Recently, McHugh and Ma's11 correlation of nurse workload with readmission rates among patients with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction and pneumonia, underlines a relationship between nursing inpatient business and readmission rates. Naylor et al's12 systematic review of care transitions describes 21 different adult inpatient interventions to reduce readmissions with emphasis on the impact of nursing-guided patient-centred interventions at the time of discharge. A systematic review by Chiu et al13 highlighted the value of nursing interventions focusing on communication tools, patient involvement, nurse-led coaching, education sessions and comprehensive discharge planning.

Studies have established the impact of pharmacist-based interventions on readmission rates and care transitions. Schnipper et al14 demonstrated that postdischarge pharmacy calls reduce adverse drug events after hospitalisation. A pharmacist coaching intervention was noted to reduce readmissions in a study by Coleman et al.9 In elderly populations, pharmacist inpatient counselling paired with outpatient pharmacist home visits has been shown to effectively reduce readmissions.15 Overall readmission rates demonstrated improvement during the MGH STAAR initiative with a 30% rate reduction from ∼21% to 14.5%; however, the isolated nursing and pharmacist interventions did not demonstrate a statistically significant change in readmissions. This may be explained by the level of collaboration and engagement by unit staff, nursing, pharmacists and physicians. Furthermore, having a single point person who can be easily identified by patients and care team served to reduce inefficiencies and further streamline care. In addition, the D/C RN role included leading discussions at multidisciplinary rounds and focused on creating consensus around the estimated day of discharge for all unit patients. This method of engaging providers and broadcasting the care plan is an effective way to improve care coordination. Having support of key stakeholders including unit and institutional leadership allowed the initiative to build momentum that may have not otherwise occurred.

Other key interventions that may have contributed to reducing readmission rates for all patients include changes to the electronic medication reconciliation application as well as the timing and structure of house staff and multidisciplinary rounds. These smaller changes had a significant impact on the flow and execution of care delivery in the unit.

Although the goal of reducing unit readmission rates to 10% was not achieved, with the implementation of the D/C RN role, pharmacy medication reconciliation, postdischarge calls and improved care coordination, several unexpected outcomes occurred. During the process of interdisciplinary collaboration, awareness of readmission rates and the importance of reducing readmissions became a top priority. Although unable to quantify the cost savings of a 30% reduction in readmission rates, our belief is that we improved patient care outcomes as defined by The Institute of Medicine. The Institute of Medicine's (IOM) Crossing the Quality Chasm describes improving health as a function of upholding the dictums of safe, effective, patient-centred, timely, efficient and equitable healthcare.16 We believe that the work detailed here holds true to the IOM values and further demonstrates the call to action for healthcare systems in general.

Limitations

Inclusion criteria may have excluded patients who could have benefitted from the interventions; therefore, the D/C RN was afforded the opportunity to include additional individuals through consensus with the unit nurse director and project manager. In addition, the project required staff nurses to take on an additional patient as part of their assignment to create a cost-neutral dedicated D/C RN. A small percentage of a pharmacy resource was dedicated to this project and balanced with other responsibilities. For these reasons, this work may not be possible at some other institutions. All high-risk patients would have benefited from the TC PharmD intervention, however, due to timing of admissions, limited pharmacy resources and other unavoidable logistics, not all of the high-risk patients received both interventions possibly reducing favourable outcomes. Reorganisation of multidisciplinary rounds and other unit-based changes may have contributed to decreased readmissions in patients who were not identified as high risk for readmission in this study. During the fourth year of the project, the D/C RN role was changed to the Attending Nurse Role and expanded to other units in the hospital as a part of an institution-wide initiative. It is unclear how this influenced findings. In 2013, there was an institution-wide effort to increase the number of warm-handoffs to postacute care facilities and the impact on outcomes was unable to be quantified. Routine house staff and attending turnover may have negatively impacted readmission rates despite efforts to bridge care gaps.

Conclusion

Single interventions, when evaluated in isolation, did not demonstrate statistically significant changes in readmission rates. A multidisciplinary approach to improving care coordination effectively reduced avoidable readmissions. This demonstrates the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration, which improved the care transitions and reduced rehospitalisations for our patients, the primary outcome measures of this quality improvement initiative.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals who contributed to this work: Theresa Gallivan, RN, Elizabeth Mort, MD, Andrew Karson, MD, Christine Annese, RN, Yanie Jackson, MBA, Gwendolyn Crevensten, MD, Christian Dankers, MD, Sarah Keegan, RN, Elizabeth Bishop, RN, Jenna Delgado, RN, Stefanie Green, RN, Catherine Mullin, RN, Joanne Kaufman, RN MPA, Laura Huber, CCM, Diane Hubbard, ACM, Lisa McDonough, RN, Patricia Durning, RN CM, Deborah Kiely, RN, Ashley Truong, PharmD, Andrea Bonnano, DPT, Regina Neives, RN and Mary Neagle.

Footnotes

Contributors: JAC designed the data collection, monitored data collection for the entire period, analysed data, and drafted and revised the paper. She is the guarantor. LSC, JC, JDP, KH, JS and LAT initiated the collaborative project, designed the data collection, monitored data collection for the entire period, analysed data, drafted and revised the paper, and revised and updated project criteria. JM initiated the collaborative project, designed the data collection, monitored data collection for the entire period, cleaned and analysed data, drafted and revised the paper, and revised and updated project criteria.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study obtained Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board (Chaired by Dr Elizabeth Hohmann, MD) ethical exemption due to the nature of the study and its quality improvement focus. Patients were informed at the time of their admission that efforts to provide optimal care by partnering with nursing and pharmacy resources would occur, and all patients were interested in these services.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.A path to bundled payment around a rehospitalization. Report to the Congress: reforming the delivery system Washington DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2005:83–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson Gerard F, Steinberg Earl P. Hospital readmissions in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med 1984;311:1349–53. 10.1056/NEJM198411223112105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez Adrian F, Greiner Melissa A, Fonarow Gregg C, et al. . Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA 2010;303:1716–22. 10.1001/jama.2010.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mistiaen P, Francke AL, Poot E. Interventions aimed at reducing problems in adult patients discharged from hospital to home: a systematic meta-review. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;747–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker SG, Peet SM, McPherson A, et al. . A systematic review of discharge arrangements for older people. Health Technol Assess 2002;6:1–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips CO, Wright SM, Kern DE, et al. . Comprehensive discharge planning with postdischarge support for older patients with congestive heart failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2004;291:1358–67. 10.1001/jama.291.11.1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards S, Coast J. Interventions to improve access to health and social care after discharge from hospital: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy 2003;8:171–9. 10.1258/135581903322029539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. . A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178–87. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, et al. . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1822–8. 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cloonan P, Wood J, Riley JB. Reducing 30-day readmissions: health literacy strategies. J Nurs Adm 2013;43:382–7. 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31829d6082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McHugh MD, Ma C. Hospital nursing and 30-day readmissions among Medicare patients with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. Med Care 2013;51:52–9. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182763284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET, et al. . The care span: the importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:746–54. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu WK, Newcomer R. A systematic review of nurse-assisted case management to improve hospital discharge transition outcomes for the elderly. Prof Case Manag 2007;12:330–6. 10.1097/01.PCAMA.0000300406.15572.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. . Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:565–71. 10.1001/archinte.166.5.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, et al. . The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Am J Med 2001;11126S–30S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington DC: National Academy Press, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]