Abstract

Importance

Depression is highly prevalent, inadequately treated, and contributes to hospitalization and other poor outcomes in older home healthcare patients. Feasible and effective interventions are needed to reduce this burden of depression.

Objective

To determine whether among older Medicare home health recipients who screen positive for depression, patients of nurses randomized to intervention have greater improvement in depressive symptoms over one year compared to patients receiving enhanced usual care.

Design

The cluster-randomized effectiveness trial randomized nurse-teams to Intervention (12 teams) or enhanced usual care (9 teams). Patients were recruited 2009–2012, assessed, and followed at 3, 6, and 12-months by research staff blind to intervention status.

Setting

Conducted at six home healthcare agencies nationwide. Patients interviewed at home and by telephone.

Participants

Medicare home health patients age ≥65 who screened positive for depression on routine nurse assessments. Of 502 eligible patients, 306 enrolled.

Intervention

Depression CAREPATH (CARE for PATients at Home) requires nurses to manage depression during routine home visits by weekly symptom assessment, medication management, care coordination, education, goal setting. Training totaled 7 hours (4 on-site, 3 web). Researchers telephoned supervisors every other week.

Main Outcome and Measure

Depression severity, assessed by 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS).

Results

306 participants were predominately female (69.6%), diverse (18.0% Black, 16.0% Hispanic), average age 76.5 (SD=8.0) years. In full sample, the intervention had no effect (treatment × time interaction: P=0.13). Adjusted HDRS scores (CAREPATH vs control) did not differ at three (10.5 vs 11.4; P=0.26) or six months (9.3 vs 10.5; P=0.12), barely reaching significance at twelve months (8.7 vs 10.6; P=0.05). In subsample with mild depression (HDRS<10), the intervention had no effect (P=.90) and HDRS did not differ at any follow-up. Among 208 participants with HDRS≥10, CAREPATH demonstrated effectiveness (P=0.02) with lower HDRS at three (14.1 vs 16.1; P=0.04), six (12.0 vs 14.7; P=0.02) and twelve months (11.8 vs 15.7; P=0.005). Exploratory analyses found no differences in number or length of home visits.

Conclusion and Relevance

Home health nurses can effectively integrate depression care management into routine practice. However, clinical benefit appears limited to only patients with moderate to severe depression.

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01979302 http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01979302

Clinically significant depression affects over 25% of older patients receiving home healthcare, twice the rate of primary care.1,2 This high prevalence is consistent with the disability, medical morbidity, and psychosocial stressors characterizing these patients. Depression is persistent and associated with suicide ideation, falls, and hospitalization in home healthcare patients, a population already at risk for adverse outcomes.3–7

This paper reports the results of a cluster-based randomized effectiveness trial targeting depressive symptoms in Medicare home healthcare patients. Medicare recommends depression screening and intervention for home healthcare patients, but interventions are needed that are clinically effective and feasible.8–13 The structure and practice of home healthcare pose challenges to this goal. First, >97% of patients are referred for medical/surgical conditions and have multiple comorbidities.14 Depression care must fit within many other clinical demands.15 Second, Medicare funds mental health services for home healthcare patients with primary psychiatric diagnoses, but the availability of specialized clinicians is inadequate and most agencies do not have psychiatric programs.16 Third, Medicare reimburses agencies for skilled nursing by payment episodes; travel and clinical costs discourage agencies from authorizing extra home visits.17

The Depression CAREPATH (CARE for PATients at Home) was developed collaboratively by researchers, homecare clinicians and administrators seeking a clinically effective intervention that could be easily integrated into routine practice.18,19 The intervention adapted key functions of Collaborative Depression Care,20 an evidenced-based approach in primary care.21–23 Collaborative Care’s cornerstone is managing depression as a chronic illness, coupling guideline-based treatment (e.g., pharmacological and/or psychotherapy) with care management. The depression care manager role was created to support primary care physicians in treating and managing patients over time.

The major innovation of CAREPATH relative to primary care’s model is that rather than assigning depression care management (DCM)to a unique individual, every homecare nurse is trained to manage depression as part of routine visits and discharge planning. The training builds on existing skills and uses terms and concepts consistent with home healthcare practice.

This study uses clinically informed research measures to determine the intervention’s effectiveness in reducing depressive severity in medical home healthcare patients with clinically significant depression. The primary hypothesis is that among patients who screen positive for depression on routine nursing assessments, patients receiving care from nurses randomized to the CAREPATH intervention would have greater reduction in depressive symptoms at three, six and twelve months compared to patients receiving enhanced usual care. Because the protocol includes further evaluation of screened-positive patients to identify patients needing active DCM, secondary analyses stratify by depression severity. With an eye towards feasibility and sustainability, the intervention’s effectiveness was tested in six heterogeneous, community-based agencies with minimal research support.

METHODS

Design, Settings and Patients

The study used a cluster-randomized design. In six home healthcare agencies, pre-existing nurse-teams were randomized to intervention or enhanced usual care. Medicare patients, age≥65, who screened positive for depression during routine nursing assessment were recruited and received structured clinical research interviews for depression severity with follow-up assessments at 3, 6, and 12-months. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Weill Cornell Medical College, Montefiore Health Care system, and Penn Health System. Patient recruitment lasted 1/2009–12/2012.

Agencies were selected for regional heterogeneity: 1. Little Rock and rural Arkansas; 2. Miami-Dade County, Florida, 3. Suburban Detroit; 4. Bronx, New York; 5. Greater Philadelphia, and 6. Rural/small town Vermont and New Hampshire. Originally planning five agencies, one was added to increase the number of randomized nurse-teams.

Nurse-teams

The unit of randomization was “nurse-team” defined by pre-existing groups of nurses and supervisors. Agencies were required to enroll ≥2 teams in the study. Within agencies, the statistician randomized teams in equal proportions to intervention or enhanced usual care; randomization of unevenly numbered teams favored intervention resulting in 12 intervention and 9 EAU teams. Team size averaged 8.5 nurses (sd=3.4) with no difference between intervention and enhanced usual care (8.3 vs 8.7; P=0.85).

Patients

Agencies used Medicare’s mandatory OASIS (Outcome and Assessment Information Set)24,25 to identify Medicare patients age≥65 who screened positive on the two-item depression screen and met other research eligibility: no dementia, life expectancy >6 months, no active suicidality, English or Spanish-speaking, and no significant hearing or speech impairment. For one year, agency personnel telephoned ≤4 eligible patients/week to introduce the study. With patients’ agreement, local research assistants (RAs) visited them at home, confirmed eligibility and obtained signed consent.

Local RAs, who were trained and supervised by Cornell investigators, conducted in-person interviews and then named a Cornell RA who telephoned within two days. Cornell RAs, referencing the in-person assessment, conducted telephone assessments at baseline and at 3, 6 and 12-month follow-up. Patients who missed interviews remained eligible for subsequent assessments. In some cases, RAs recorded information from family members. Local and Cornell RAs were blind to participants’ intervention status. When detecting active suicide risk, RAs followed structured protocols and consulted study clinicians who, in 29 instances, contacted participants’ physicians or emergency services.

Intervention Groups

The Depression CAREPATH Intervention includes both a clinical protocol and infrastructure support. The intervention and its development were described in detail previously18,19 and briefly below.

Infrastructure Development

Researchers helped agencies develop suicide risk protocols, determine referral procedures, and integrate the protocol into their electronic clinical management system.

Clinical Protocol

The clinical protocol was designed for patients who screen positive on OASIS’s two-item depression screen, currently the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ2).26 Positive screens were defined as PHQ2 ≥3 or comparably on preceding OASIS.

The protocol’s first step was assessing depression severity using the nine-item PHQ (PHQ9), a brief questionnaire used widely in medical settings.27 For patients scoring PHQ9≥10, nurses followed depression care management (DCM) guidelines during routine visits on a weekly basis (or each visit if seen less frequently). DCM required no additional home visits. Clinical functions were: 1. Assess depressive symptoms weekly using PHQ9; 2. Coordinate care with physicians and/or specialists as clinically indicated (e.g., worsening symptoms; no improvement); 3. Manage side effects and adherence to antidepressant medications; 4. Educate patients and families; 5. Assist patients with feasible, short-term goals (e.g., grooming, socializing). Nurses were expected to monitor symptoms of patients with lower PHQ9 scores.

Researchers provided separate four-hour, in-person trainings on depression assessment and DCM, each followed a month later by a three-hour web-booster. Nurses were not informed when patients enrolled in the study and were expected to follow CAREPATH’s protocol regardless of patients’ research participation. Researchers remained in contact with intervention teams through 30-minute telephone conferences with team supervisors every other week.

Enhanced Usual Care

Nurses had full access to resources generated during infrastructure development. They participated in depression assessment training. They did not receive DCM training and were expected to follow agencies’ standard procedures for depression. Team supervisors were not offered telephone support.

Outcomes and Covariates

Outcome

Depression severity was measured at all assessments using the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS),28 a clinically informed, structured interview administered reliability by telephone.29,30 The study psychiatrist, psychologist, and PI reviewed all information from each interview to determine consensus HDRS scores. The HDRS inter-rater reliability among Cornell RAs was 0.92 based on 34 independently rated interviews. Consistent with prior research, clinically significant depression was defined as HDRS≥10.21,31–35

Covariates

Sociodemographic: age, gender, self-reported race and ethnicity, marital status, education, living alone, poverty using federal criteria; Disability: limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL);36 Medical burden: Chronic Disease Scale (CDS)37; Depression Diagnosis: Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders (SCID),38 reviewed during HDRS consensus conference to determine major or minor depression (MMDD); Depression Treatment: antidepressants, psychotherapy; Cognitive status: Minimental Status Examination (MMSE).39

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

Sample Size

In planning, power was simulated in a 3-level hierarchical linear mixed model (patients nested within nurse, nurse within team, team within agency). Sample size of 5×4×5×5=500 and 15% attrition were assumed. Two intraclass correlations (ICC) reflecting variations in subject within nurse (ICC1) and nurse within team (ICC2) were modeled and assumed equal ICC1=ICC2=.05. Based on a two-sided α=0.05, the study had 92% power to detect a 0.5 standardized difference (Cohen’s d) or 3.45 HDRS points change from baseline. The final sample was smaller than anticipated due to unexpectedly high exclusion rate but sufficiently large to detect clinically meaningful effects due to low observed ICC.

Descriptive Statistics

All covariates were tested for group differences using chi-square or generalized Fisher’s test (as appropriate) for categorical variables and t-test or Wilcoxon’s rank sum test (as appropriate) for continuous variables.

Longitudinal Analysis of HDRS

The primary analysis of HDRS change from baseline involved all participants (N=306) in a longitudinal mixed effect model with intervention, time trend parameter(s) and intervention × time as fixed effects and a subject level random intercept using SAS 9.3. Secondary analyses first estimated a longitudinal model of the full sample with baseline depression severity (BDS; defined by HDRS<10 vs HDRS≥10) as intervention moderator. The analysis then stratified by BDS. The moderator analysis, additional fixed effects for moderator, moderator × intervention, moderator × time, moderator × time2 and moderator × time × intervention were modeled. A random intercept for patients clustered within nurse-team resulted in zero ICC, hence nurse-team cluster effect was adjusted as a fixed covariate. Post-hoc tests for treatment difference at different time points were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Holms step-down procedure that controls family-wise error rate.40 The effect size (Cohen’s d) for treatment difference was based on the mixed model estimated least-square means and standard deviations (raw) at 3, 6, and 12 months.

RESULTS

Subject Flow

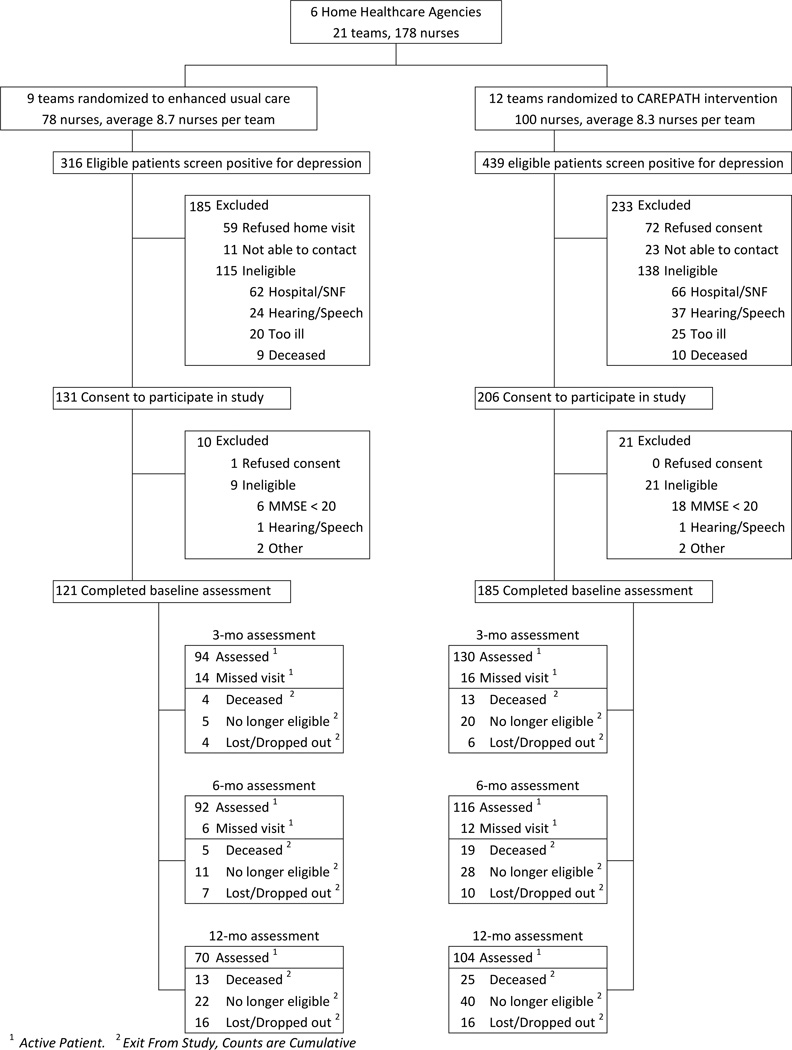

Using OASIS data, 755 patients screened positive for depression and met other eligibility criteria. Of these, 253 were no longer eligible when contacted due to hospitalization (n=128), medical severity (n=45), hearing/speech impairment (n=61) or death (n=19). Of the 502 remaining eligible, 337 consented, 131 refused, and 34 could not be contacted. The consent rate did not differ between intervention and enhanced usual care but varied by OASIS-recorded race/ethnicity (60.5% whites, 100% Hispanics, 77.3% blacks; P<.001) and decreased with age (P=.007). In the home, 306/337 consented patients met full eligibility criteria, 30 were determined ineligible (24 for dementia), and one withdrew.

Participant characteristics

Participant age ranged from 65 to 98, 18.0% were black, 16.0% were Hispanic, and 39.5% met poverty criteria. Participants reported substantial disability and medical burden. Half (51%) were taking antidepressants and 68.0% had MMDD. Compared to enhanced usual care, intervention patients had greater IADL disability and were less likely to live alone or have MMDD (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participantsa

| Full Sample | Intervention | Enhanced | Statistical Test of | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual Care | Group Difference | ||||

| Total | n=306 | n= 185 | n= 121 | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | Range 65 – 98 | 76.5 (8.0) | 76.1 (7.9) | 77.1 (8.2) | p=0.32 |

| Gender, N (%) | Female | 213 (69.6) | 126 (68.1) | 87 (71.9) | p=0.48 |

| Education in years, mean (SD) | Range 3–22 | 12.0 (3.5) | 11.9 (3.5) | 12.0 (3.4) | p=0.93 |

| Race, N (%) | White | 247 (80.7) | 147 (79.5) | 100 (82.6) | p=0.49b |

| Black | 55 (18.0) | 36 (19.5) | 19 (15.7) | ||

| Other c | 4 (1.3) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.7) | ||

| Ethnicity, N (%) | Hispanic | 49 (16.0) | 33 (17.8) | 16 (13.2) | p=0.28 |

| Marital Status, N (%) | Married | 93 (30.4) | 58 (31.4) | 35 (28.9) | p= 0.43 |

| Widowed | 127 (41.5) | 80 (43.2) | 47 (38.8) | ||

| Other | 86 (28.1) | 47 (25.4) | 39 (32.2) | ||

| Lives Alone, N (%) | Lives Alone | 142 (46.7) | 77 (42.1) | 65 (53.7) | p=0.05 |

| Income Below Poverty, N (%) d | Poverty | 83 (39.5) | 47 (37.9) | 36 (41.9) | p=0.56 |

| Source of Referral to Home Health, N (%) | Outpatient | 44 (14.4) | 26 (14.1) | 18 (14.9) | p=0.70 |

| Hospital | 165 (53.9) | 97 (52.4) | 68 (56.2) | ||

| Rehab or SNF e | 97 (31.7) | 62 (33.5) | 35 (28.9) | ||

| Number of ADL Limitations, mean (SD) | Range 0 – 6 | 1.4 (1.6) | 1.5 (1.7) | 1.2 (1.4) | p=0.10 |

| Number of IADL Limitations, mean (SD) | Range 0 – 6 | 3.3 (1.6) | 3.5 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.7) | p=0.03 |

| Reported Medical Conditions, mean (SD) | Range 1 – 15 | 6.1 (2.5) | 6.1 (2.5) | 6.0 (2.5) | p=0.54 |

| Number of prescription meds mean (SD) | Range 0 – 22 | 9.0 (4.0) | 9.3 (3.8) | 8.6 (4.2) | p=0.11 |

| CDS Medical Burden score, mean (SD) | Range 0 – 18 | 6.0 (3.0) | 6.2 (2.9) | 5.7 (3.2) | p=0.17 |

| Cognitive Status (MMSE), mean (SD) | Range 20 – 30 | 26.8 (2.6) | 26.6 (2.7) | 27.1 (2.6) | p=0.10 |

| Antidepressant Prescription, N (%) | Current | 157 (51.3) | 100 (54.1) | 57 (47.1) | p=0.24 |

| SCID Depression Diagnosis (MMDD), N (%) | Current | 208 (68.0) | 117 (63.2) | 91 (75.2) | p=0.03 |

| Depression Severity (HDRS24), mean (SD) | Range 0 – 39 | 14.2 (7.8) | 13.7(7.7) | 15.0 (7.8) | p=0.13 |

Abbreviations: ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Independent Activities of Daily Living; MMSE, Minimental Status Examination; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders

Missing data ≤5 participants unless otherwise noted

White vs Other race categories

Includes Native American (n=3) and Asian (n=1)

Data on 210 participants

Hospital to rehabilitation hospital/skilled nursing facility to home health

The sample’s distribution of primary diagnoses (submitted to Medicare) was similar to national statistics, differing only by more circulatory disease and injuries, and fewer skin conditions (Table 2). Primary diagnoses did not differ by group.

Table 2.

Principal ICD-9-CM Diagnosis of Persons Using Medicare Home Health Agency Services: National Data (2012) and Study Sample

| National 1,2 | Full Sample | Intervention | Enhanced | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual Care | ||||||||

| ICD-9 | n=3,460,000 | n=306 | n= 185 | n= 121 | ||||

| Principal ICD-9-CM Diagnosis (Major Diagnostic Category)3 | Codes | Percent4 | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent |

| Infectious and Parasitic Diseases (MDC 1) | 001–139 | 0.8% | 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.8% |

| Neoplasms (MDC 2) | 140–239 | 3.2% | 13 | 4.3% | 8 | 4.3% | 5 | 4.1% |

| Endocrine, Nutritional, Metabolic, Immunity Disorders (MDC 3) | 240–279 | 10.5% | 33 | 10.8% | 19 | 10.3% | 14 | 11.6% |

| Diseases of the Blood and Blood Forming Organs (MDC 4) | 280–289 | 1.7% | 2 | 0.7% | 1 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.8% |

| Mental Disorders (MDC 5)5 | 290–319 | 2.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Diseases of the Nervous System and Sense Organs (MDC 6) | 320–389 | 4.7% | 13 | 4.3% | 7 | 3.8% | 6 | 5.0% |

| Diseases of the Circulatory System (MDC 7) | 390–459 | 27.6% | 109 | 35.6% | 66 | 35.7% | 43 | 35.5% |

| Diseases of the Respiratory System (MDC 8) | 460–519 | 9.3% | 27 | 8.8% | 20 | 10.8% | 7 | 5.8% |

| Diseases of the Digestive System (MDC 9) | 520–579 | 2.7% | 8 | 2.6% | 6 | 3.2% | 2 | 1.7% |

| Diseases of the Genitourinary System (MDC 10) | 580–629 | 3.2% | 11 | 3.6% | 8 | 4.3% | 3 | 2.5% |

| Diseases of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue (MDC 12) | 680–709 | 6.7% | 9 | 2.9% | 6 | 3.2% | 3 | 2.5% |

| Disease of Musculoskeletal/Connective Tissue (MDC 13) | 710–739 | 13.0% | 39 | 12.8% | 22 | 11.9% | 17 | 14.1% |

| Congenital Anomalies (MDC 14) | 740–759 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Symptoms, Signs, and Ill-Defined Conditions (MDC 16) | 780–799 | 6.5% | 12 | 3.9% | 7 | 3.8% | 5 | 4.1% |

| Injury and Poisoning (MDC 17) | 800–999 | 6.3% | 29 | 9.5% | 15 | 8.1% | 14 | 11.6% |

| Supplementary Classification of Factors | V01-V82 | 36.3% | 58 | 19.0% | 37 | 20.0% | 21 | 17.4% |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of Information Services: Data from the Standard Analytical Files; Medicare & Medicaid Statistical Supplement 2013 edition. Table 7.6: Persons Using Medicare Home Health Agency Services, Visits, Total Charges, Visit Charges, and Program Payments, by Principal Diagnosis Within Major Diagnostic Classifications (MDCs): Calendar Year 2012

3,460,000 persons served

ICD-9-CM is International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (Volume 1). Only the first listed or principal diagnosis has been used.

percentiles based on total of MD1-MD17 V-Codes Numbers may not add up due to rounding and exclusion of MDC11 and MDC 14 from the national data base due to small numbers. Consistent with the presentation of national data, the total of MDC1 – MDC17 = 100% and V-Codes are percentiled separately.

By design, the study did not recruit patients from behavioral health programs and therefore has no patient having mental disorder as a primary diagnosis

Depression severity (HDRS) averaged 14.2 (sd 7.8, range 0–39). The majority (68.0%) scored HDRS≥10 with no significant difference between study groups. Participants with HDSR≥10, compared to less depressed participants, were younger (75.6 vs 78.3 years; P=.005), more disabled (1.54 vs 1.13 ADLs; P=.03), and more likely taking antidepressants (55.3% vs 41.8%; P=0.03). Among HDRS≥10, intervention differed from enhanced usual care by greater antidepressant use (61.5% vs 47.7%, P=.05; etable 1).

Of 306 participants, 254 had at least one follow-up interview; 174 completed the final interview. In a multivariate model, noncompletion was associated with being Hispanic (OR=2.79; 95% CI, 1.465 to 5.34), ADL disability (OR=1.17; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.57) and greater medical burden (OR=1.09; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.18). Among HDRS≥10, 170/208 had at least one follow-up; 115 completed the final interview. Noncompleters were more likely to be Hispanic (OR=2.67; 95% CI, 1.18 to 6.06), had more ADL disability (OR=1.2; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.45) and greater medical burden (OR=1.15; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.26). Intervention participants did not differ from enhanced usual care in either set of noncompleters.

Primary analyses

Improvement of depressive symptoms (HDRS) from baseline was analyzed with the full sample (N=306) in a mixed effects model for months 3, 6 and 12 with treatment, time2, treatment × time as fixed effects and adjusted for the agency-nurse-team cluster, IADL, use of anti-depressants, MMDD, gender and living alone as covariates. Adjusted HDRS scores did not differ between CAREPATH and enhanced usual care at three months (10.5 vs 11.4; P=0.26) or six months (9.3 vs 10.5; P=0.12). Twelve months HDRS difference did reach significance (8.7 vs 10.6; P=0.05) but the treatment × time interaction was not significant (p=0.13).

Secondary analyses

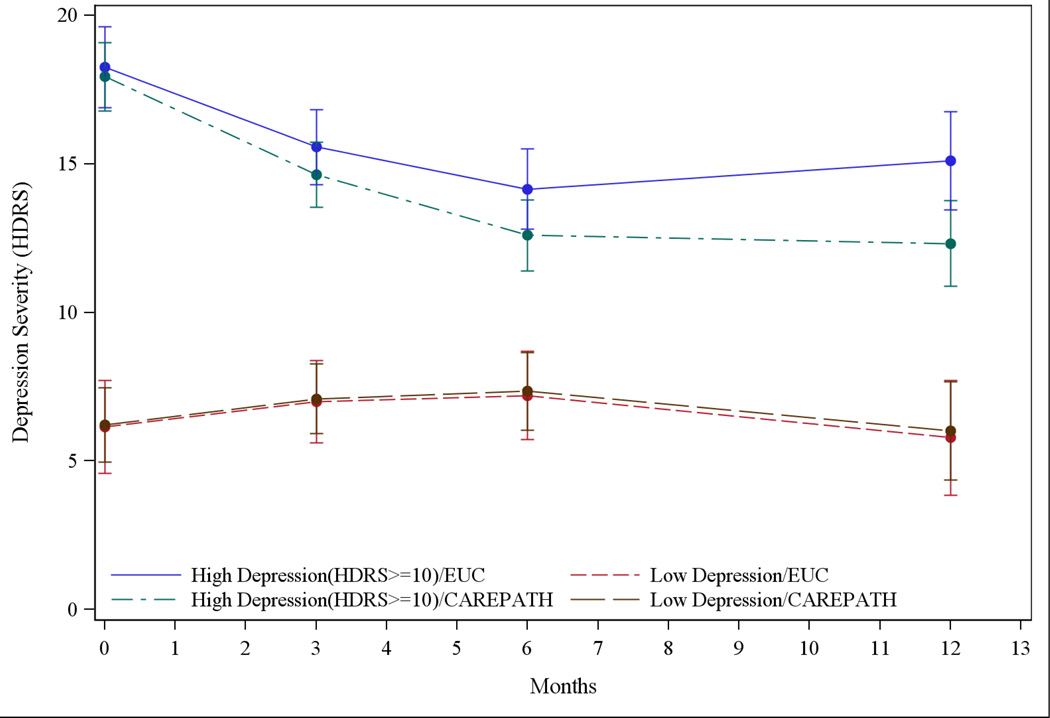

The moderator analysis examined depression severity (HDRS) over time in four groups defined by both intervention status and baseline depression severity (BDS). The analysis found no significant (P=0.12) three-way interaction (time × BDS × intervention) after controlling for IADL, living alone and agency-nurse-team cluster as covariates. In stratified analysis of HDSR≥10 participants, time (P<.001), time2 (P<.001) and time × intervention (P=0.02) all differed significantly from zero after controlling for baseline anti-depressant use, IADL, living alone and agency-nurse-team cluster as fixed covariates. These findings indicate that HDRS decreased over time in both groups but the reduction was significantly greater in CAREPATH compared to enhanced usual care (Figure 2). The group difference in HDRS scores was tested at each follow-up (Table 3).40 CAREPATH participants had significantly lower HDRS scores than enhanced usual care at three months (14.1 vs 16.1; P=0.04), six months (12.0 vs 14.7; P=0.02) and twelve months (11.8 vs 15.7; P=0.005). Change in HDRS from baseline to one year also differed significantly between groups (5.6 vs 3.1 points; P=0.02).

Figure 2.

Course in the Severity of Depressive Symptoms over Time, Stratified by Group and Baseline Depression Severity

Least square mean depression severity (HDRS) and 95% confidence intervals at baseline and 3, 6, 12 month follow-up. Top two lines compare Enhanced Usual Care (blue, solid line) to CAREPATH (green, dot-dashes) among participants scoring HDRS≥10 at baseline. The bottom two lines compare Enhanced Usual Care (red, short dashes) to CAREPATH (brown, long dashes) among participants HDRS<10.

Table 3.

Group Difference in Depressive Symptoms at each Time Point: Participants with Clinically Significant Depression (HDRS≥10)a,b

| Month | HDRS Difference | Unadjusted P-value | Adjusted P-valuec | Lower | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (CAREPATH-Enhanced Usual Care) | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||

| 0 | −1.4 | 0.17 | |||

| 3 | −2.0 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −4.0 | −0.10 |

| 6 | −2.7 | 0.009 | 0.017 | −4.65 | −0.69 |

| 12 | −4.0 | 0.002 | 0.005 | −6.34 | −1.50 |

Abbreviations: CAREPATH, Depression CAREPATH Intervention; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

n=208 (122 CAREPATH, 86 EUC)

Linear mixed model controlling for limitations in activities of daily living, depression diagnosis, gender and marital status.

P-value adjusted for multiple comparisons using Holm’s stepdown procedure40

In less depressed (HDRS<10) participants, there was no difference between groups (time × intervention P=0.90).

Exploratory Analyses

The modifying effect of depression diagnosis (MMDD) was explored in a mixed model (as described in Methods) and found a significant intervention difference between CAREPATH and enhanced usual care in the MMDD group (11.7 vs 14.8; P=0.005) at 12 months but no difference (6.9 vs 6.6; P=0.88) in the non-depressed group. The three-way interaction (MMDD × intervention × time) was, however, not significant (P=0.15). Stratified analysis had similar conclusion as BDS and hence not presented here.

Mixed model analyses with patients HDRS≥10 found no significant difference in the intervention by baseline antidepressant use (time × intervention × antidepressant [P=0.84];treatment × antidepressant (P=0.57]). Intervention vs enhanced usual care differences in 12 month HDRS change from baseline did not differ (P=0.84) by baseline antidepressant use (6.0 vs 3.5 and 4.8 vs 2.7 among antidepressant users and non-users respectively).

To explore the influence of somatic symptoms, the model was reanalyzed using a 6-item HDRS mood subscale.41–43 Among patients HDRS≥10, the time × intervention effect trended towards significance (P=.10) after controlling for baseline antidepressants, IADL, living alone and agency-nurse-team cluster as fixed covariates. CAREPATH participants had significantly lower mood scores than enhanced usual care at 6 months (4.6 vs 5.5; P=0.03) and at 12 months (4.7 vs 6.0; P=0.03).

The impact on service delivery was explored using administrative data. Among HDRS≥10, average duration of service did not differ between groups (CAREPATH=64.1 days vs enhanced usual care=64.7 days, P=0.94). Visit data (available from only one agency) showed no group differences in the average number (11.0 visits vs 12.4 visits; P=0.42) or duration of nursing visits (54.5 minutes vs 59.9 minutes; P=0.18).

DISCUSSION

The principal finding is that among medical home healthcare patients who screen positive for depression, a home health nursing intervention did not improve depression scores overall. However, among the sub-group with more significant depression, the intervention was associated with greater decrease in depressive symptoms compared to enhanced usual care. The difference between groups was significant at three months, growing larger and more clinically meaningful over one year.

The potential implications of these findings need to be placed in the context of study limitations. First, agencies were diverse in size and location but not strictly representative of certified home healthcare agencies. Although agencies had minimal research experience, their leaderships’ agreement to participate suggests greater support for practice change than average. Second, study participants represent only patients with sufficient cognitive functioning and willingness to participate in research. Third, we cannot explain higher consent rates among minority and younger patients. These factors and attrition due to death, illness or cognitive decline may affect generalizability. With these caveats, our findings can be examined from several perspectives.

Study participants were homebound older adults with substantial medical burden and disability. Like most (>97%) Medicare home healthcare patients, their primary diagnosis was medical/surgical, not mental.14 The heterogeneity in primary diagnoses is consistent with the national profile of home healthcare patients and suggests the study’s generalizability across patients. Depression adds to personal suffering, family burden, and risk of hospitalization, falls, and other poor outcomes.5–7,44 Among patients with clinically significant depression, the CAREPATH intervention was associated with a 5.6 point decline in HDRS, indicating meaningful changes in depression severity (e.g., from moderate to mild; mild to minimal) and consistent with interventions in primary care.21 Effect sizes at 6 and 12 months (Cohen’s d: 0.32 and 0.49 respectively) were also consistent with primary care studies 45–48 and considered beneficial by the Community Preventive Service Task Force.49 But, like most primary care studies, the majority of intervention patients continued to experience meaningful depressive symptoms despite improvement. Both medical and social factors affect the course of depression in late life and this finding points to both the limits of the home healthcare intervention and the importance of individualized treatment decision-making.50–52

Medicare strengthened depression screening by adding the PHQ2 to the OASIS. Like most screens, the PQH2 is not a definitive measure but identifies patients with a higher likelihood of having clinically meaningfully symptoms. The study’s “negative finding” -- no intervention effect among all screen-positive patients – is consistent with this goal of screening. The Depression CAREPATH uses the PHQ9, a brief measure of depressive severity,27 to help nurses narrow screened-positive patients to those with greatest need. The findings suggest that investing in further evaluation is efficient and effective.

Finding no intervention effect among patients with mild depression is consistent with the protocol’s instructions to only monitor milder symptoms which may, in effect, resemble usual care. This finding is similar to interventions tested in primary care for subsyndromal depression.21,53 It differs, however, in that mild symptoms generally improved in primary care whereas symptoms persisted in home healthcare. These results suggest that more active interventions may be needed or that subsyndromal symptoms indicate more stable phenomena.54,55

Medicare recognizes psychiatric home healthcare as a billable service if patients’ primary diagnosis is a mental disorder (ICD9 290–319) requiring active treatment and services are provided by a “psychiatrically trained nurse”.56 The impetus for developing the Depression CAREPATH was evidence that depression is prevalent and burdensome in medical home healthcare patients coupled with reluctance expressed by administrators to develop specialty services, increase personnel or reduce nurse productivity. Researchers worked with clinicians and administrators to develop an intervention that was clinically effective, feasible and acceptable to medical nurses. The resulting Depression CAREPATH followed principles of Collaborative Depression Care, an approach that fits naturally with home healthcare where nurses serve as the “eyes and ears” of physicians who are responsible for these services.57 However, CAREPATH modified Collaborative Care to fit routine home healthcare practice. Clinical tasks were defined in home healthcare terms and consistent with job expectations.15,58 Nurses were not asked to make treatment decisions (e.g., prescribe) or provide psychotherapy. Rather, they were asked to care for depression as they care for other chronic diseases.

Exploratory analyses found no difference in the impact of the intervention by whether or not patients were already taking antidepressants. This finding is important as half the participants were taking antidepressants, many with guideline-consistent doses. In this context, active symptoms suggest the current antidepressant regime is ineffective and patients may benefit from change (e.g., dose, switching, augmentation and/or the non-specific benefit of care management).59

Evidence that medical homecare nurses can effectively integrate depression care into routine practice is also important given the Institute of Medicine report documenting the scarcity of qualified mental health providers in home healthcare and elsewhere for the rapidly aging population.16 The report recommends expanding capacity by building on skills of other clinicians and paraprofessionals. Thus while this study focused on home healthcare, the approach may be relevant to other populations.

Of importance to administrators, the CAREPATH was designed to fit within the constraints and routine practice. Depression management was integrated into already scheduled visits and did not require or result in additional or longer home visits. The protocol itself was simple enough to integrate key elements into five commercial clinical software systems.

From the broader perspective, the impact of the intervention continued to grow over one year. Medicare pays for short-term home healthcare (e.g., 60 day episodes).14 This long term benefit may indicate a cumulative effect starting, perhaps, with assessing depression in the home environment and integrating depression into both care coordination and “handoff”. These tasks are consistent with many innovative models of transitional and post-hospitalization care, suggesting that addressing depression is both feasible and potentially useful.60–65

Conclusion

Clinically significant depression is common in patients receiving Medicare home health services and associated with poor outcomes. Medicare recommends depression screening and intervention, but the clinical needs of home healthcare patients, the scarcity of mental health specialists, as well as the structure and practice of home healthcare pose challenges to this goal. This effectiveness trial demonstrates that home healthcare nurses can effectively integrate depression care management into routine practice with the clinical benefit to moderate to severely depressed patients extending beyond the home health service period.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Consort Table

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH082425; P30 MH085943; T32 MH019132; T32 MH073553; K01 MH073783).

Role of the Sponsor: The National Institutes of Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Bruce had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Bruce, Leon, Raue, Reilly, Greenberg, Meyers, Sheeran

Acquisition of data: Bruce, Raue, Reilly, Greenberg, Meyers, Pickett, Ghesquiere, Zukowski, Rosas, McLaughlin, Pledger, Doyle, Joachim

Analysis and interpretation of data: Bruce, Raue, Reilly, Greenberg, Meyers, Banerjee, Pickett

Drafting of the manuscript: Bruce, Raue, Reilly, Greenberg, Meyers, Banerjee

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Bruce, Raue, Reilly, Greenberg, Meyers, Banerjee, Pickett, Sheeran, Ghesquiere, Zukowski, Rosas, McLaughlin, Pledger, Doyle, Joachim

Statistical Analysis: Bruce, Greenberg, Banerjee

Obtained funding: Bruce, Leon, Raue

Administrative, technical, or material support: Bruce, Meyers, Ghesquiere, Zukowski, Rosas, McLaughlin, Pledger, Doyle, Joachim, Sheeran

Study supervision: Bruce, Raue, Reilly, Greenberg, Pickett, Sheeran, Zukowski, McLaughlin, Pledger, Doyle, Joachim

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Bruce reported receiving personal fees for consultation from McKesson and other support from Medispin. Dr. Pickett reports receiving salary from Montefiore Medical Center’s Department of Psychiatry. Ms. Zukowski reports receiving personal fees from Zone Program Integrity Contracts (ZPIC). No other authors reported conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer: The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Additional contributions:

We give special acknowledgement to the late Andrew C. Leon, PhD (Weill Cornell Medical College) who collaborated in the study design and preparation of the grant proposal. Judy Pomerantz, RN, MS provided consultation and training in depression care management. Yuhua Bao, PhD (Weill Cornell Medical College) provided consultation. We acknowledge the research assistants who helped with the day-to-day data collection: Kisha Bazelais, PhD; Stephanie Charles, BA; Rebecca James, MA; Jennifer Lotterman, MS; Christina Mele, BS; Melissa Mezo, BS; and Daniel Sugrue, BA (all from Weill Cornell Medical College). All of the people acknowledged above were compensated for their work on this study. Finally, we thank all of the investigators, clinicians, patients and their families for their contributions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruce ML, McAvay GJ, Raue PJ, et al. Major depression in elderly home health care patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 Aug;159(8):1367–1374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyness JM, Caine ED, King DA, Cox C, Yoediono Z. Psychiatric disorders in older primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1999 Apr;14(4):249–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raue PJ, Meyers BS, McAvay GJ, Brown EL, Keohane D, Bruce ML. One-month stability of depression among elderly home-care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003 Sep-Oct;11(5):543–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raue PJ, Meyers BS, Rowe JL, Heo M, Bruce ML. Suicidal ideation among elderly homecare patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007 Jan;22(1):32–37. doi: 10.1002/gps.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byers AL, Sheeran T, Mlodzianowski AE, Meyers BS, Nassisi P, Bruce ML. Depression and risk for adverse falls in older home health care patients. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2008 Oct;1(4):245–251. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20081001-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheeran T, Brown EL, Nassisi P, Bruce ML. Does depression predict falls among home health patients? Using a clinical-research partnership to improve the quality of geriatric care. Home Healthc Nurse. 2004 Jun;22(6):384–389. doi: 10.1097/00004045-200406000-00007. quiz 390–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheeran T, Byers AL, Bruce ML. Depression and increased short-term hospitalization risk among geriatric patients receiving home health care services. Psychiatr Serv. 2010 Jan;61(1):78–80. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delaney C, Fortinsky R, Doonan L, Grimes RLW, Pearson TL, Bruce ML. Depression screening and interventions for older home health care patients: program design and training outcomes for a train-the-trainer model. Home Health Care Management and Practice. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ell K, Unutzer J, Aranda M, Gibbs NE, Lee PJ, Xie B. Managing depression in home health care: a randomized clinical trial. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2007;26(3):81–104. doi: 10.1300/J027v26n03_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gitlin LN, Harris LF, McCoy MC, et al. A home-based intervention to reduce depressive symptoms and improve quality of life in older African Americans: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Aug 20;159(4):243–252. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-4-201308200-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suter P, Suter WN, Johnston D. Depression revealed: the need for screening, treatment, and monitoring. Home Healthc Nurse. 2008 Oct;26(9):543–550. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000338514.85323.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madden-Baer R, McConnell E, Rosati RJ, Rosenfeld P, Edison I. Implementation and evaluation of a depression care model for homebound elderly. Journal of nursing care quality. 2013 Jan-Mar;28(1):33–42. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e318265702a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markle-Reid MF, McAiney C, Forbes D, et al. Reducing depression in older home care clients: design of a prospective study of a nurse-led interprofessional mental health promotion intervention. BMC geriatrics. 2011;11:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services. Medicare & Medicaid Statistical Supplement. (2013 edition) 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hennessey B, Suter P. The home-based chronic care model. Caring. 2009 Jan;28(1):12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine. The Mental Health and Substance Use Workforce for Older Adults: In Whose Hands? 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Health Care Financing Review: Medicare & Medicaid Statistical Supplement. (2009 Edition) 2009 https://www.cms.gov/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/10_2009.asp#TopOfPage.

- 18.Bruce ML, Raue PJ, Sheeran T, et al. Depression Care for Patients at Home (Depression CAREPATH): home care depression care management protocol, part 2. Home Healthc Nurse. 2011 Sep;29(8):480–489. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0b013e318229d75b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruce ML, Sheeran T, Raue PJ, et al. Depression care for patients at home (Depression CAREPATH): intervention development and implementation, part 1. Home Healthc Nurse. 2011 Jul-Aug;29(7):416–426. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0b013e31821fe9f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katon W, Unutzer J, Wells K, Jones L. Collaborative depression care: history, evolution and ways to enhance dissemination and sustainability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010 Sep-Oct;32(5):456–464. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004 Mar 3;291(9):1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002 Dec 11;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Bruce ML, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009 Aug;166(8):882–890. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Outcome and Assessment Information Set-B1. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. OASIS-C Guidance Manual for 2010 Implementation. 2009 Chapter 3: J-4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003 Nov;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960 Feb;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potts MK, Daniels M, Burnam MA, Wells KB. A structured interview version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: evidence of reliability and versatility of administration. J Psychiatr Res. 1990;24(4):335–350. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(90)90005-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon GE, Revicki D, VonKorff M. Telephone assessment of depression severity. J Psychiatr Res. 1993 Jul-Sep;27(3):247–252. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(93)90035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, et al. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991 Sep;48(9):851–855. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810330075011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams JW, Jr, Barrett J, Oxman T, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: A randomized controlled trial in older adults. JAMA. 2000 Sep 27;284(12):1519–1526. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penninx BW, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, van Eijk JT, Guralnik JM. Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: longitudinal evidence from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1999 Sep;89(9):1346–1352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, Bula CJ, Hohmann C, Beck JC. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med. 1999 Feb;48(4):445–469. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989 Aug 18;262(7):914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969 Autumn;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Von Korff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K. A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992 Feb;45(2):197–203. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90016-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders (SCID) Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association Press, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bech P, Allerup P, Gram LF, et al. The Hamilton depression scale. Evaluation of objectivity using logistic models. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1981 Mar;63(3):290–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1981.tb00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bech P, Gram LF, Dein E, Jacobsen O, Vitger J, Bolwig TG. Quantitative rating of depressive states. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1975 Mar;51(3):161–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1975.tb00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Licht RW, Qvitzau S, Allerup P, Bech P. Validation of the Bech-Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale and the Hamilton Depression Scale in patients with major depression; is the total score a valid measure of illness severity? Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2005 Feb;111(2):144–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilkins VM, Bruce ML, Sirey JA. Caregiving tasks and training interest of family caregivers of medically ill homebound older adults. J Aging Health. 2009 Jun;21(3):528–542. doi: 10.1177/0898264309332838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ekers D, Murphy R, Archer J, Ebenezer C, Kemp D, Gilbody S. Nurse-delivered collaborative care for depression and long-term physical conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of affective disorders. 2013 Jul;149(1–3):14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller CJ, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron BE, Kilbourne AM, Woltmann E, Bauer MS. Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions: cumulative meta-analysis and metaregression to guide future research and implementation. Med Care. 2013 Oct;51(10):922–930. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a3e4c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2012 May;42(5):525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2. CD006525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Community Preventive Services Task F. Recommendation from the community preventive services task force for use of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders. Am J Prev Med. 2012 May;42(5):521–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet. 2005 Jun 4–10;365(9475):1961–1970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andreescu C, Mulsant BH, Houck PR, et al. Empirically derived decision trees for the treatment of late-life depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;165(7):855–862. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nelson JC, Delucchi K, Schneider LS. Efficacy of second generation antidepressants in late-life depression: a meta-analysis of the evidence. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;16(7):558–567. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181693288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barrett JE, Williams JW, Jr, Oxman TE, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: a randomized trial in patients aged 18 to 59 years. The Journal of family practice. 2001 May;50(5):405–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abrams RC, Rosendahl E, Card C, Alexopoulos GS. Personality disorder correlates of late and early onset depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994 Jul;42(7):727–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Markowitz JC, Skodol AE, Petkova E, et al. Longitudinal comparison of depressive personality disorder and dysthymic disorder. Compr Psychiat. 2005 Jul-Aug;46(4):239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual Publication number 100–02. 2014 Chapter 7, 40:41.42.15. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hennessey B, Suter P. The Community-Based Transitions Model: one agency’s experience. Home Healthc Nurse. 2011 Apr;29(4):218–230. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0b013e318211986d. quiz 231–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suter P, Hennessey B, Harrison G, Fagan M, Norman B, Suter WN. Home-based chronic care. An expanded integrative model for home health professionals. Home Healthc Nurse. 2008 Apr;26(4):222–229. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000316700.76891.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kennedy GJ, Marcus P. Use of antidepressants in older patients with co-morbid medical conditions: guidance from studies of depression in somatic illness. Drugs & aging. 2005;22(4):273–287. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. Journal of hospital medicine : an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2007 Sep;2(5):314–323. doi: 10.1002/jhm.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 Apr 2;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lattimer C. Practices to improve transitions of care: a national perspective. North Carolina medical journal. 2012 Jan-Feb;73(1):45–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Sep 25;166(17):1822–1828. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET, Olds DM, Hirschman KB. The care span: The importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health affairs. 2011 Apr;30(4):746–754. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed March 1, 2014];Community-based Care Transitions Program. 2014 http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/CCTP/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.