Abstract

The substituted cysteine accessibility method was applied to single Cx46 hemichannels to identify residues that participate in lining the aqueous pore of channels formed of connexins. Criteria for assignment to the pore included reactivity to sulfydryl-specific methanethiosulfonate (MTS) reagents from both sides of an open hemichannel and observable effects on open channel properties. We demonstrate reactivity to MTS reagents over a stretch of seventeen amino acids, D51 through L35, that constitute segments of E1 and TM1. Qualitatively, the nature of the effects caused by the Cys substitutions alone and their modification with MTS reagents of either charge indicate side chain valence is most influential in determining single channel properties with D51 and L35 defining the extracellular and intracellular limits, respectively, of the identified pore-lining region. A number of Cys substitutions beyond L35 in TM1 caused severe alterations in hemichannel function and precluded assignment to the pore. Although all six subunits can be modified by smaller MTS reagents, modifications appear limited to fewer subunits with larger reagents.

Keywords: Connexin, cystein scanning, gap junction, rectification, unitary conductance

INTRODUCTION

The solution of the crystal structure of the bacterial K+ channel at 2 Å resolution represents a milestone in the study of ion channel structure-function (19). However, this approach is still impractical for many ion channels, including connexins, which lack bacterial counterparts. Alternative techniques, such as electron cryomicroscopy applied to 2-D crystals of isolated junctional membranes have achieved ~6–7 Å resolution for connexins, and have provided sufficient structural detail to visualize helices and their packing arrangement (3, 16). A potential limitation of structural approaches for ion channels is that it is not entirely clear what, if any, physiological state of a channel a crystal structure represents and molecular genetic and biophysical techniques applied to channels in living cells are invaluable complementary approaches for generating structure-function relationships and modifying or refining existing structural models. An approach that has proved valuable in determining structure-function relationships of proteins in living cells, particularly in the identification of pore-lining and gating domains of ion channels, is the Substituted Cysteine Accessibility Method, or SCAM (6). Individual amino acid residues mutated to Cys are mapped to provide structure based on accessibility to hydrophilic sulfhydryl-specific reagents. Here we illustrate results of a single channel SCAM approach utilizing Cx46 hemichannels to identify connexin channel pore-lining domains.

METHODS

In this study, the first transmembrane domain (TM1) of Cx46 is defined as residues K23 through A41 and the first extracellular loop (E1) as residues E42 through R67 (1). Individual Cys-mutants were constructed by PCR mutagenesis using appropriate oligonucleotides as detailed in Kronengold et al. (7)

Preparation of Xenopus oocytes, methods of preparing and injecting mRNA in Xenopus oocytes, and details of obtaining patch clamp recordings of hemichannel currents in Xenopus oocytes have been described previously (15). In this study, internal pipette solutions (IPS) and bathing solutions consisted of (in mM) 140 KC1, 5 EGTA, 1 CaC12, 1 MgC12, 5 HEPES and pH was adjusted to 7.6 with KOH. MTS reagents, 2-aminoethy1 methanethiosulfonate (MTS-EA+), 2-trimethylammonioethy1 methanethiosulfonate (MTS-ET+), 2-sulfonatoethylmethane thiosulfonate (MTS-ES−) and N-biotinylcaproylaminoethyl methanethiosulfonate (MTSEA-BIOTINCAP) were purchased from Biotium Inc. (Hayward, CA). For each experiment, aliquots of dry powder were dissolved in distilled water or DMSO and diluted into IPS just prior to application to the desired final concentration. MTS reactions were monitored in excised patches containing single hemichannels recorded in symmetric IPS solutions at fixed voltages and perfusing the bath with freshly prepared MTS reagent. Reactivity typically occurred within seconds of MTS-ET+ application at concentrations of 0.5 to 1mM. Hemichannel I–V curves were obtained before and after MTS application by applying 8 sec voltage ramps from −70 to +70 mV. Currents were acquired at 10 kHz with PCI-MIO-16XE D/A boards from National Instruments (Austin, TX) using our own acquisition software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Single Channel SCAM

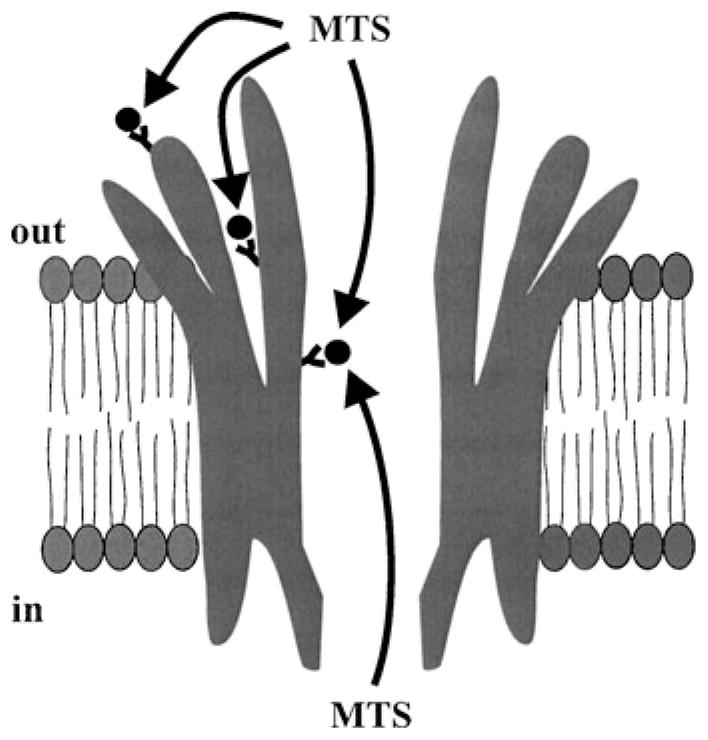

SCAM has been used to identify pore-lining residues in ion channels based on rapid accessibility to hydrophilic modifying reagents. However, accessible residues not only reside in the pore, but also on the channel surface as well as in aqueous crevices as described for the K+ channel (2). In addition, conformational changes that accompany channel gating, whether generated by changes in membrane potential or the binding of chemical agents, can alter the subset of accessible residues (5). However, the pore is unique in that it represents an aqueous domain confluent with both the intra- and extracellular aqueous compartments when the channel is in the open state. Thus, in an open channel, pore-lining residues should be uniquely accessible from either side of the membrane (Figure 1). Monitoring the open state of a channel requires single-channel recording, which, together with accessibility from either side, is readily achieved by using connexin hemichannels in excised inside-out or outside-out patch configurations (14). SCAM at the single channel level allows immediate separation of effects on gating from those on open channel properties and an ability to assess whether effects of modification are consistent with residence in the pore.

Figure 1.

Schematic of a connexin hemichannel embedded in a cell membrane with Cys-substituted residues illustrated at three locations, on the extracellular surface, in a crevice facing the extracellular space and in the channel pore. In an open channel, Cys residues on the surface or in crevices are accessible to MTS modification from only one side of the membrane whereas Cys residues in the pore are uniquely accessible from either side.

E1 and TM1 Contribute to the Pore of Cx46 Hemichannels

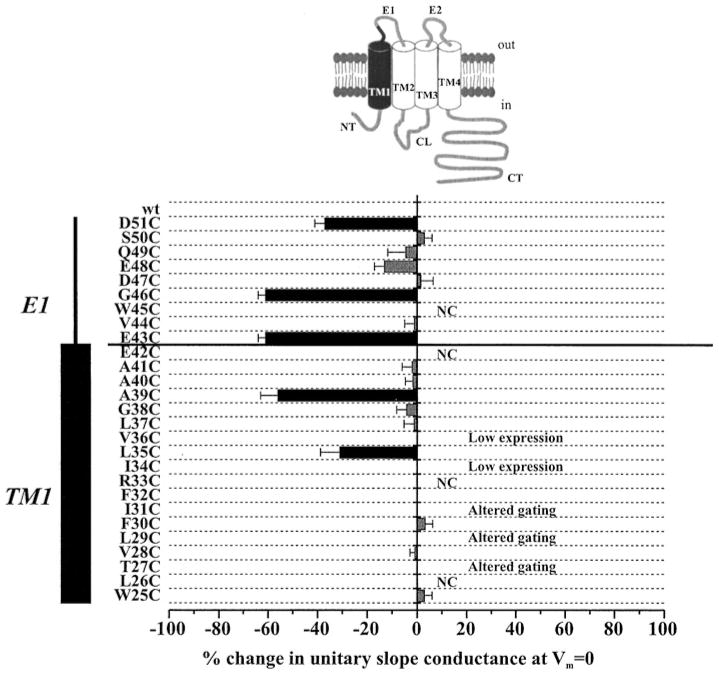

Figure 2 summarizes results of single channel SCAM of 27 residues, W25 through D51, which initiates near the cytoplasmic border of TM1 and extends through the entire transmembrane span and ~10 residues into E1. Using the positively charged MTS-ET+ reagent, changes in open hemichannel properties were observed with reagent added to either side of the membrane at 5 positions, L35, A39, E43, G46 and D51, which span over 17 residues. At each position, application of MTS-ET+ resulted in a substantial decrease in unitary conductance and reduced open-channel rectification that persisted after washout of reagent. Since wt Cx46 hemichannels are cation-selective, with PK:PCI exceeding 10:1 (15), the decrease in conductance at each position can be explained by a reduction in the K+ concentration in the pore, the major current-carrying ion, due to introduction of fixed positive charge upon modification with MTS-ET+. Modification of D51C had the largest effect on open channel rectification consistent with a location closest to the outer vestibule of the hemichannel pore. Thus, it appears that the accessible residues likely follow the accepted connexin topology with D51 the furthest extracellular and successive positions proceeding towards the cytoplasm.

Figure 2.

SCAM with MT-SET+ shows El and TMl contribute to the Cx46 hemichannel pore. Results are summarized for residues D51 through W25, which span the regions shaded in black in the illustration of a connexin subunit. The change in unitary conductance represents the mean% change in the slope conductance relative to the corresponding Cys substituted mutant measured at Vm = 0 from fitted open channel I–V relations. Data from excised patches of either configuration showed no differences and are pooled together with cell-attached recordings of pre-reacted oocytes. Error bars represent standard deviations; n ≥ 10 for each mutant. NC denotes non-functional hemichannels. Accessibility of mutants exhibiting low expression and altered gating could not be satisfactorily characterized at the single channel level.

Whereas most Cys-substitutions in E1 and the extracellular end of TM1 formed hemichannels with near wild-type properties, Cys-substitutions in TM1 towards the cytoplasmic end significantly affected channel behavior. Over a span of 12 residues, W25 through V36, 7 had altered function. L26C and R33C failed to form functional hemichannels, I34C and V36C had low expression levels, and T27C, L29C and I31C exhibited severely altered gating. Although none of the remaining five residues showed evidence of accessibility to MTS-ET+, contribution of this region of TM1 to the pore remains uncertain due to an inability to evaluate a large number of residues. The high sensitivity of this region of TM1 to mutation, with no apparent pattern along a helical face, suggests that TM1 may tilt or bend away from the pore, thereby establishing interactions with other TM domains that are important for the functional integrity of the hemichannel.

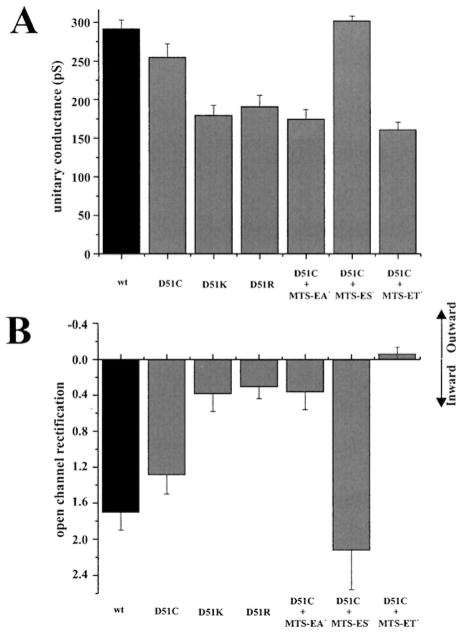

Side-Chain Charge Has a Strong Influence on Open Channel Properties

Comparison of the effects of Cys-substitution alone, and modification with MTS-ET+ or MTS-ES−, indicates that side-chain charge is the property that is most important for the observed effects on unitary conductance and open-channel rectification (Figure 3). Modification of D51C with MTS-ET+, which results in a considerably larger side chain than the naturally occurring Asp or the substituted Cys, results in a large decrease in unitary conductance. However, modification with MTS-ES−, which results in a similarly large side chain as MTS-ET+ but of opposite charge, produces an increase rather than a decrease in conductance consistent with charge as the determinant factor. The importance of charge in determining open channel properties is also evident by comparing the effects of substitution with Arg or Lys or modification with MTS-ET+ or MTS-EA+, all of which result in a side chain containing positive charge and all of which produce rather similar effects. Substitutions with residues containing large, branched, but uncharged side chains can also substantially reduce conductance as indicated in the next section.

Figure 3.

Summary of data comparing unitary conductance (A) and open-channel rectification (B) in hemichannels in which D51 was modified to Lys or Arg or Cys unreacted or reacted with MTS-EA+, MTS-ES−, or MTS-ET+. Unitary conductance is the slope conductance at Vm = 0 obtained from fitted open channel I–V relations. Open hemichannel current rectification is the ratio of the currents at −70 mV and at +70 mV (L−70/I+70 for inward rectification and I+70/I−70 for outward rectification; a ratio of 1.0 indicates a linear I–V relationship). Data represent means and standard deviations. Data for conductance and rectification are from the same patches.

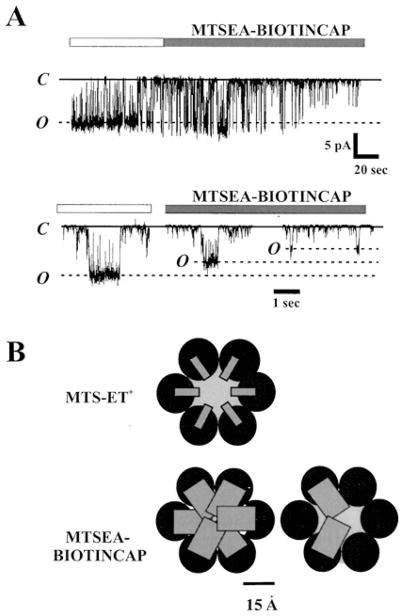

Molecularity of MTS Reactions

Several lines of evidence indicate all six subunits in a Cys-substituted Cx46 hemichannel are modified by MTS-ET+ and MTS-ES− (7). In contrast, examination of the D51C hemichannel using a large MTS reagent, such as MTSEA-BIOTINCAP (MW = 495), suggests that fewer subunits may be modified. Application of MTSEA-BIOTINCAP resulted in a similar final reduction in unitary conductance as with MTS-ET+, but the change in conductance occurred with only two discernable step-changes ascribable to reactions on two subunits (Figure 4A). Since the resulting side chain with MTSEA-BIOTINCAP is neutral, the effects are likely steric rather than electrostatic in nature. The reduced molecularity of reactions may result from interference of one or two reacted subunits that, in turn, prevent further accessibility (Figure 4B). A single step-change in conductance was reported in Cx32*Cx43E1 chimeric hemichannels at L35C using the large maleimide, MBB, as the thiol reagent (9), and may be indicative of accessibility limited to a single subunit. Such steric restrictions may explain, in part, the relatively small changes in current observed in SCAM studies of Cx32 and Cx46 using MBB (10, 11, 18).

Figure 4.

Accessibility appears to be limited to fewer subunits with a larger MTS reagent. (A) Example of an MTSEA-BIOTINCAP modification of a D51C hemichannel. Shown is a current record obtained from an outside-out patch containing a single D51C hemichannel; membrane potential was held constant at +30 mV and 1.0 mM MTSEA-BIOTINCAP was applied to the bath (indicated by the bar). Two reductions in unitary current were evident and examples are shown in expanded views. Dashed lines indicate open states of unmodified and modified hemichannels; solid lines denote the fully closed state. Gating was altered upon modification, but was not examined in detail. (B) Schematics of MTS modified hemichannels with boxes representing volumes of Cys side chains modified by MTSET (upper hemichannel) and MTSEA-BIOTINCAP (lower hemichannels). The side chains are scaled relative to each other based on space-fill models and placed to produce an arbitrary pore diameter of 15 Å when all six subunits are modified by MTS-ET+. The same diameter pore would be occluded if all subunits were modified by MTSEA-BIOTINCAP (lower left), but size would likely preclude reactivity at all six subunits leaving hemichannels maximally reacted with fewer subunits (lower right).

SUMMARY

The identities of the pore-lining segments of Cx46 are emerging with El contributing at the extracellular end continuing into TMl as the channel enters the membrane. The pattern of reactivity is consistent with an α-helical secondary structure from L35 through G46 (7). D51 does not fall on the same side of the helix and may represent a transitional region between the transmembrane α-helix and the β-sheet ascribed to the extracellular loops by Foote et al. (4)

Skerrett et al. (10) reported TM3 as pore-lining throughout the transmembrane span of Cx32 channels based on MBB accessibility. Our examination of the extracellular end of TM3 in Cx46 hemichannels, a region that corresponds topologically with the accessible region of TMl, has shown no evidence of MTS-ET+ accessibility (7). A helical packing arrangement from the 3D structure of Unger et al. (16) suggests two helices could potentially be accessible at the extracellular end of the transmembrane span, which could be TMl and TM3.

Although we did not see evidence of MTS-ET+ accessibility in TM3 of Cx46, other MTS reagents differing in size and charge should be examined for completeness. Accessibility of the cytoplasmic end of TM3 remains untested in Cx46 at the single hemichannel level. At the cytoplasmic end of the channel, the N-terminal domain has been proposed to form the vestibule of the pore in Cx32 and Cx26 (17), a possibility also supported by the possibility that charged residues in the N-terminus of Cx40 are critical for open channel block by spermine (8). Therefore, a number of domains appear to contribute to the pore along its length including El at the extracellular end, possibly TMl and TM3 in the transmembrane span, and NT at the cytoplasmic end.

Gap junction channels made up of different connexin isoforms differ significantly in ionic and molecular selectivity, conductance and open channel current rectification. Interestingly, the notion of a large pore, on the order of 15 Å based on tracer studies, does not preclude a small ionic conductance as demonstrated by the neuronal Cx36 channel, which exhibits a conductance of ~l5ps, yet passes tracers such as Neurobiotin (12, 13). Our SCAM studies suggest that these two seemingly inconsistent properties can be reconciled by the arrangement of fixed charges in the pore. The determinants of ionic conductance in large channels such as connexins are contributed by the global (total) charge profile of all residues that line the pore in contrast to the highly-localized and specialized selectivity filters of Na+ and K+ channels (19). As we have shown here by examining the same amino acid positions reacted with MTS-ET+ or MTS-ES−, conductance can be substantially altered without significant changes in side chain size, and by inference, the pore diameter. The expectation is that the presence of both negative and positive charges in the pore will lead to small conducting connexin channels that are still capable of passing tracer molecules.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Angele Bukauskiene for extraordinary technical assistance. J. K. was supported by training grant TS-NS07439. This study was supported by NIH Grant GM54179 to V.K.V.

References

- 1.Bennett MV, Barrio LC, Bargiello TA, Spray DC, Hertzberg E, Saez JC. Gap junctions: New tools, new answers, new questions. Neuron. 1991;6:305–320. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90241-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cha A, Bezanilla F. Structural implications of fluorescence quenching in the Shaker K+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:391–408. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.4.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng A, Schweisinger D, Dawood F, Kumar N, Yaeger M. 3D structure of full length connexin43 by electron cryo-crystallograpgy. Cell Commun Adhes. 2003;10(4–6) doi: 10.1080/cac.10.4-6.187.191. this volume. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foote CI, Zhou L, Zhu X, Nicholson BJ. The pattern of disulfide linkages in the extracelluar loop regions of connexin 32 suggests a model for the docking interface of gap junctions. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1187–1197. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horn R. Coupled movements in voltage-gated channels. J Gen Phys. 2002;120:449–453. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlin A, Akabas MH. Substituted-cysteine accessibility method. Methods Enzymol. 1998;293:123–145. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)93011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kronengold J, Trexler EB, Bukauskas FB, Bargiello TA, Verselis VK. Single channel SCAM identifies pore-lining residues in the first extracellular loop and first transmembrane domains of Cx46 hemichannels. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:389–405. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musa H, Veenstra RD. Voltage-dependent blockade of connexin40 gap junctions by spermine. Biophys J. 2003;84:205–219. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74843-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfahnl A, Dahl G. Localization of a voltage gate in connexin46 gap junction hemichannels. Biophys J. 1998;75:2323–2331. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77676-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skerrett IM, Aronowitz J, Shin JH, Cymes G, Kasperek E, Cao FL, Nicholson BJ. Identification of amino acid residues lining the pore of a gap junction channel. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:349–360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skerrett IM, Kasperek E, Shin JH, Ahmed S, Nicholson BJ. Mapping conformational changes associated with gap junction channel gating using a disease-related mutation. Cell Commun Adhes. 2003;10(4–6) this volume. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srinivas M, Rozental R, Kojima T, Dermietzel R, Mehler M, Condorelli DF, Kessler JA, Spray DC. Functional properties of channels formed by the neuronal gap junction protein Connexin36. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9848–9855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-09848.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teubner B, Degen J, Söhl G, Güldenagel M, Bukauskas FF, Trexler EB, Verselis VK, De Zeeuw CI, Lee CG, Kozak CA, Petrasch-Parwez E, Dermietzel R, Willecke K. Functional expression of the murine connexin36 gene coding for a neuron specific gap junctional protein. J Membr Biol. 2000;176:249–262. doi: 10.1007/s00232001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trexler EB, Bennett MV, Bargiello TA, Verselis VK. Voltage gating and permeation in a gap junction hemichannel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5836–5841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trexler EB, Bukauskas FF, Kronengold J, Bargiello TA, Verselis VK. The first extracellular loop domain is a major determinant of charge selectivity in connexin46 channels. Biophysical Journal. 2000;79:3036–3051. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76539-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unger VM, Kumar NM, Gilula NB, Yeager M. Three-dimensional structure of a recombinant gap junction membrane channel. Science. 1999;283:1176–1180. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5405.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verselis VK, Ginter CS, Bargiello TA. Opposite voltage gating polarities of two closely related connexins. Nature. 1994;368:348–351. doi: 10.1038/368348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou XW, Pfahl A, Werner R, Hudder A, Llanes A, Luebke A, Dahl G. Identification of a pore lining segment in gap junction hemichannels. Biophys J. 1997;72:1946–1953. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78840-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Y, Morais-Cabral JH, Kaufman A, MacKinnon R. Chemistry of ion coordination and hydration revealed by a K+ channel-Fab complex at 2.0 A resolution. Nature. 2001;414:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35102009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]