Abstract

Background

Metanephric Adenoma (MA) of the kidney is a rare indolent tumor that may be difficult to differentiate from other small renal masses. Genetic alterations associated with MA remain largely unknown.

Objectives

We aimed at defining genetic events in MA of the kidney and determining their influence in the management of this disease.

Design, setting, and participants

Multiplexed mass spectrometric genotyping was performed on 29 MA cases after tumor DNA extraction. We also conducted a mutational screen in additional 129 renal neoplasms. Immunohistochemistry was performed on the MA cases to assess molecular markers of signaling pathway activation. Patients’ baseline characteristics as well as follow up data were captured.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics for baseline clinical characteristics and incidence of mutations; Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to correlate patient characteristics and mutational status.

Results and Limitations

We identified the BRAF V600E mutation in 26/29 MA cases. These results were validated in all cases using the commercially available BRAF Pyro Kit (QIAGEN). In contrast, BRAF mutations were rare in the other 129 non-MA renal neoplasms that were screened. We detected a BRAF mutation (V600E) only in one papillary RCC case. In all MA tumors, we documented expression of p-MEK, p-ERK, accompanied by immunoreactivity for p16 (INK4a). All patients were treated with a partial or radical nephrectomy and, after a median follow-up of 26.5 months, there were no local or distant recurrences. Limitations include the retrospective nature of this study.

Conclusions

BRAF V600E mutations are present in ~90% of all MA cases, serving as a potential valuable diagnostic tool in the differential diagnosis of small renal masses undergoing a percutaneous biopsy. Further, the presence of BRAFV600E and MAPK activation in a largely benign tumor supports the necessity for secondary events (e.g. p16 loss) in BRAF driven oncogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Metanephric adenoma (MA) is a rare kidney neoplasm recognized by the 2004 WHO classification of kidney tumors. The incidence range varied from 0.2 to 1% in the largest series of localized disease, likely higher in smaller tumors.1,2 MAs are generally considered benign kidney tumors with low proliferation rate, and only rarely cases of regional lymph node metastasis and sarcomatoid changes have been reported.3,4,5 MA presents as small renal mass (SRM) and is treated with surgery (radical or partial nephrectomy) with the potential of significant renal insufficiency, leading to increased cardiovascular and overall mortality.6 On enhanced CT, most cases are hypovascular with lower attenuation than the renal parenchyma and cannot be differentiated from a malignancy such as renal cell carcinoma (RCC).3

The histopathological diagnosis of MA can also be challenging. The differential diagnosis includes epithelial-predominant Wilms tumor (WT) and the solid variant of papillary RCC, both with a potential for an aggressive behavior.7,8 To date, the genetic basis of MA of the kidney remains largely unknown. Indeed, very limited studies have focused on the genetic analysis of this kidney tumor subtype.9,10 The identification of genetic alterations associated with MA could lead to the development of diagnostic biomarkers for this disease. Thus, we interrogated tissue samples using a mass spectrometric method that tests for the presence of a large number of cancer-associated mutations in MA specimens.11

METHODS

Patients and samples

Fresh frozen samples or formalin fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks from the departments of pathology at 4 institutions, including Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), Mayo Clinic, Stanford University and Cleveland Clinic were retrieved and reviewed by expert genitourinary pathologists at each institution (MSH, JC, JKM, MZ); the diagnosis of MA was then re-confirmed by a single pathologist (SS). DNA was extracted from whole tissue sections (20 cases) or 0.6 mm-diameter tissue cores (9 cases) using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (QIAGEN). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the analysis of the anonymized tissues (Protocol DFCI# 09-122). Clinical parameters such as age, gender, race, involved side, symptoms at presentation, surgical procedure, and follow up data were collected.

Mass spectrometric genotyping

Multiplexed mass spectrometric genotyping was performed on 7 MA cases from BWH using the OncoMap platform as described in prior publications.11,12 Briefly, genomic DNA was whole genome amplified using the REPLI-g Mini kit (QIAGEN) and used as input for multiplex PCR followed by probe extension. Products were transferred to SpectroCHIPs (SEQUENOM) for analysis by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Allele peaks were analyzed and candidate mutations were validated using the Multiple Base Extension (MBE) chemistry. Primers and probes used for MBE validation were designed using the Sequenom Assay Design 3.0 software. Twenty-two additional MA samples obtained from other institutions were analyzed for multiple BRAF mutations using the MBE chemistry. Specifically, 17 assays were designed to screen for 22 unique nucleotide changes in BRAF corresponding to 20 unique amino acid changes (Supplemental Table 1). To screen for BRAF mutations in other kidney tumor types (as controls), OncoMap analysis was also carried out on a series of 70 clear cell RCCs, 25 papillary RCCs, 21 chromophobe RCCs, 8 oncocytomas, and 5 renal angiomyoadenomatous tumors (total of 129 tumors).

Pyrosequencing

A different method of DNA sequencing was performed to confirm the BRAF V600E mutations. Briefly, DNA extracted from all 29 MA cases was amplified and sequenced at the Center for Advanced Molecular Diagnostics at the BWH using the BRAF Pyro Kit (QIAGEN) designed to detect mutations in codon 600. The Kit was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. GTCTCAGTCGTATGTAGTCTAG was used as the nucleotide dispensation order.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, heated with a pressure cooker to 125°C for 30 seconds in citrate buffer and then incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide, avidin block (Vector) for 15 minutes, and serum-free protein block (Dako) for 10 minutes. The primary antibodies (anti-p-ERK from Cell Signaling Technology, Cat #4370, 1:3000; anti-p-MEK from Cell Signaling Technology, Cat #2338, 1:3000; anti-p16/INK4, from Millipore, Cat #04-239, 1:2) were applied for 1 hour. Detection was performed by incubation with Dako EnVision+ System (Dako) for 30 minutes. For p-ERK and p-MEK, slides were then incubated with Biotin labeled tyramide (Perkin-Elmer) at a 1:50 dilution for 10 minutes, followed by LSAB2 Streptavidin-HRP (Dako) for 30 minutes. DAB chromogen (Dako) was then applied. Positive (high expressing) and negative (low expressing) controls cells for p-ERK and p-MEK were provided by Cell Signaling Technology (Cat #8103 and # 11126). The percentage of positive tumor cells was evaluated by a single pathologist (SS).

RESULTS

Identification of BRAF mutations by mass spectrometric genotyping

Twenty-nine cases of MA were identified and retrieved for molecular analysis. The clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Median age was 54 years (range: 25–78 years) and female to male ratio was 26:3. One patient presented with hematuria only and the rest of patients had the mass detected as an incidental finding. Median tumors’ size was 2.7 cm (range 1.2–6.6 cm). Three patients were treated with radical nephrectomy and the rest of patients had partial nephrectomy. At a median follow up of 26.5 months, there were no local or distant recurrences.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patient no. | Age, y | Gender | Treatment | Tumor Size(cm) |

Pathologic Stage |

BRAF Status |

Follow-up date, months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort I | |||||||

| 1 | 41 | F | PN | 3.5 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 128 |

| 2 | 53 | M | PN | 3.6 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 7 |

| 3 | 54 | F | PN | 2 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 101 |

| 4 | 35 | F | PN | 1.5 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 34 |

| 5 | 75 | F | PN | 2.2 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 127 |

| 6 | 31 | F | RN | 4 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 11 |

| 7 | 40 | F | RN | 7 | pT1b | BRAF V600E | 6 |

| Cohort II | |||||||

| 8 | 60 | F | PN | 2.3 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 26.5 |

| 9 | 25 | F | PN | 1.2 | pT1a | WT | 46 |

| 10 | 40 | F | PN | 2.2 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 24 |

| 11 | 60 | F | PN | 1.6 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 15.5 |

| 12 | 68 | F | PN | 4.2 | pT1b | BRAF V600E | 24 |

| 13 | 78 | F | PN | 3.5 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 78 |

| 14 | 75 | M | PN | 2 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 39 |

| 15 | 70 | F | PN | 1.8 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 5 |

| 16 | 57 | F | PN | 5 | pT1b | BRAF V600E | NA |

| 17 | 63 | F | PN | 6.6 | pT1b | BRAF V600E | 13 |

| 18 | 61 | F | RN | 3.5 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 63 |

| 19 | 67 | F | PN | 5 | pT1b | BRAF V600E | 27 |

| 20 | 36 | F | PN | 2.1 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 93 |

| 21 | 38 | F | PN | 1.2 | pT1a | WT | 47 |

| 22 | 43 | F | PN | 4.7 | pT1b | BRAF V600E | 1 |

| 23 | 33 | F | PN | 3.6 | pT1a | WT | 4 |

| 24 | 46 | F | PN | 3.1 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 32 |

| 25 | 50 | F | PN | 2.7 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 30 |

| 26 | 43 | F | PN | 4.4 | pT1b | BRAF V600E | 7 |

| 27 | 67 | M | PN | 1.3 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 13 |

| 28 | 56 | F | PN | 2.1 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | 15 |

| 29 | 55 | F | PN | 2 | pT1a | BRAF V600E | NA |

NA indicates not available; RN: radical nephrectomy; PN: partial nephrectomy; WT: wild type; BRAF V600E: V600E Mutation in the BRAF gene

To investigate the presence of oncogenic mutations in MA, we initially analyzed 7 tumors from BWH using the OncoMap platform. A mutation in BRAF resulting in the V600E variant protein (where valine is substituted for glutamic acid) was identified in all 7 samples. No other mutations were found. A second independent set of 22 FFPE MA samples from several institutions was then analyzed using a custom MBE experiment with 17 assays interrogating 22 nucleotide changes in BRAF corresponding to 20 amino acid mutations, including BRAF V600E (Supplemental Table 1). The BRAF V600E mutation was found in 19 of the 22 samples and 3 samples were deemed to be wild-type. No other BRAF mutations were detected.

In contrast to MA and in line with previously published results, BRAF mutations were rare in the other 129 non-MA renal neoplasms that were screened. We detected a BRAF mutation (V600E) only in one papillary RCC case. In this case, the diagnosis of papillary RCC was re-confimed by one pathologist (SS). Moreover, cytogenetic analysis revealed the presence of trisomy of chromosomes 7 and 17, characteristic of papillary RCC. Clinical data, available for 87 of the 129 analyzed cases, are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Validation of BRAF mutations by pyrosequencing

To confirm the presence of BRAF V600E in MA, we utilized an independent technology from a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA) certified laboratory. Specifically, all 29 samples were pyrosequenced at the Center for Advanced Molecular Diagnostics at the BWH. The concordance rate between our mass spectrometric genotyping and the pyrosequencing was 100%. All the 26 samples with BRAF V600E mutation as well as the 3 wild-type specimens were confirmed on subsequent pyrosequencing. Overall, BRAF V600E mutations were present in 26/29 (~90%) of tested MA cases. In all positive samples, the rate of mutant to wild type alleles was approximately 50%. Given the estimated high tumor purity (>95%) of the samples submitted for analysis, this finding is consistent with the presence of a heterozygous BRAF mutation in the vast majority of tumor cells. In 5 cases in which germline DNA (extracted from uninvolved kidney tissue) was also analyzed, no BRAF V600E mutations were detected.

Correlation between patient characteristics and mutational status

Correlation of molecular results with clinical data revealed that the median age was significantly higher in subjects with MA harboring BRAF mutation (55 years) than in subjects with MA without mutation (33 years) (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p=0.012). The median size of mutant tumors tended to be larger (2.9 cm) compared with non-mutant tumors (1.2 cm) (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p=0.123). There was no association between other clinical characteristics (Table 1) and the presence of BRAF V600E.

Immunohistochemical analysis

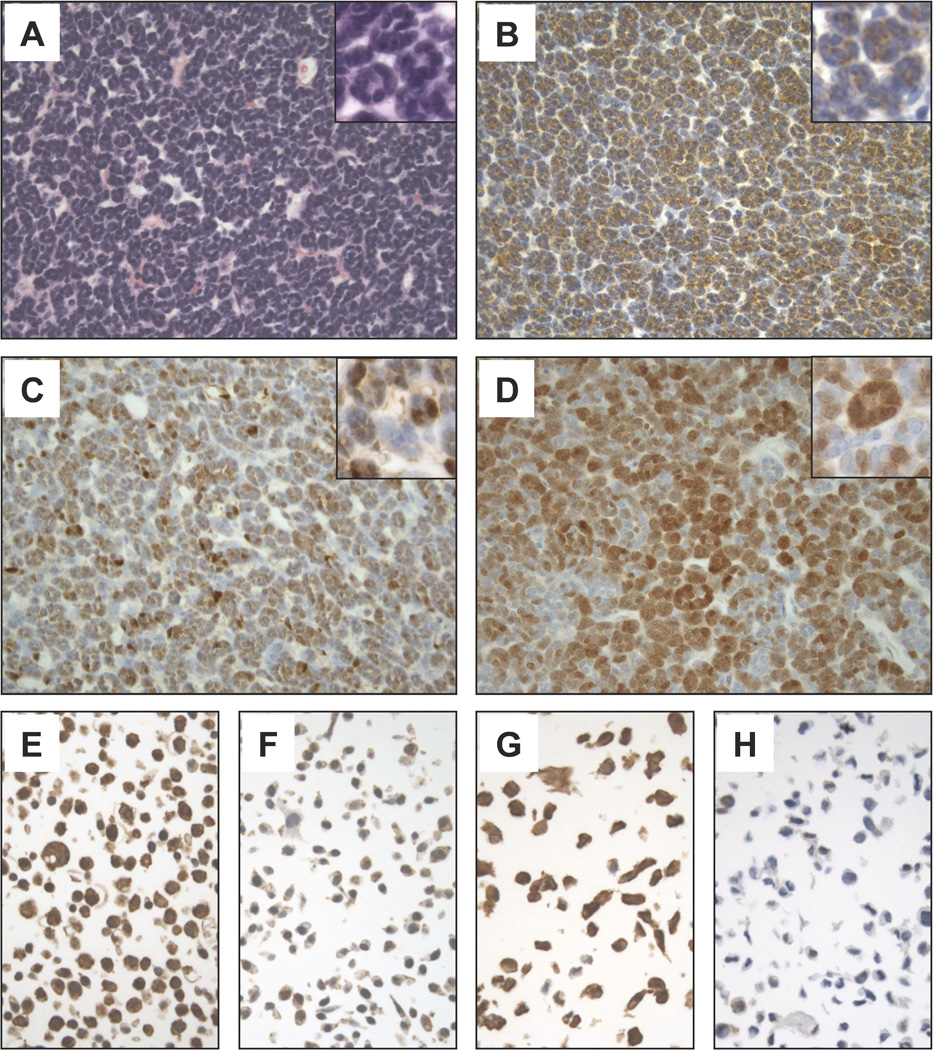

Since BRAF V600E may activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascade, we investigated the expression of phosphorylated MEK (p-MEK) and phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in a subset of 22 MA cases, including one wild-type and 21 mutant cases. Positive staining for p-MEK and p-ERK was detected in all tumors (Figure 1B, C). The percentage of positive tumor cells, however, varied significantly among the different cases and ranged from <1% to 80% (median: 45%) for p-MEK and from 10% to 80% (median: 60%) for p-ERK. The BRAF wild-type MA showed positivity for p-MEK and p-ERK in 50% and 30% of tumor cells, respectively. In morphologically normal kidney cortex adjacent to the tumors, p-ERK was found to be expressed in glomeruli, endothelial cells and a subset of kidney tubules while no consistent p-MEK expression was detected.

Figure 1.

Representative microscopic images (400×) of a BRAF-mutant MA case stained with Hematoxilyn and Eosin (A) or immunostained for p-MEK (B), p-ERK (C), or p16 (INK4a) (D). Microscopic images (600×) of high- (E, G) and low-expressing (F, H) control cell lines used for the optimization of p-MEK (E, F) and p-ERK (G, H) immunoassays are also shown.

The presence of BRAF V600E has been documented not only in malignant tumors but also in more indolent or benign neoplasms, including, Langerhans cell histiocytosis13, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas14, and melanocytic nevi15. In these slow growing neoplasms, BRAF V600E is thought to induce senescence through a mechanism that involves p16 (INK4a). Therefore, we immunostained our MA cases with an anti-p16 (INK4a) specific antibody. Notably, all 22 analyzed tumors demonstrated nuclear p16 (INK4a) immunoreactivity with a percentage of positive tumor cells ranging from 5% to 60% (median: 25%) (Figure 1D). No significant p16 (INK4a) staining was detected in the In morphologically normal kidney cortex adjacent to the tumors (not shown).

DISCUSSION

In our study, we provide for the first time evidence that a specific mutation in the BRAF gene is present in 90% of metanephric adenomas. Our results first obtained through mass spectrometric genotyping were all confirmed using a commercially available pyrosequencing test.

The specific BRAFV600E mutation has been commonly found in several tumors. More than 50% of cutaneous melanomas, one-third of papillary thyroid cancers, and likely all cases of hairy cell leukemia carry mutations in BRAFV600E with activation of downstream signaling through the MAPK pathway.16,17 As a proof of concept, patients with metastatic melanoma harboring such mutations experience an improved survival with a BRAF kinase inhibitor.18 The mutation is found at a much lower frequency in a wide range of other human cancers.19 On the other hand, BRAF V600E is also present in more indolent tumors including melanocytic nevi (moles). The latter lesions are usually benign and very rarely progress to aggressive melanomas despite the presence of BRAF mutations. One theory is that BRAF mutations in this situation can induce cellular senescence, which limits the proliferative capacity of a pre-malignant process, acting as a mechanism of intrinsic tumor suppression. There is evidence that sustained BRAFV600E expression in human melanocytes and other cell types leads to cell cycle arrest, through induction of the tumor suppressor gene p16 (INK4a).20,21,22 Of note, the CDKN2A locus is frequently lost or silenced in melanoma16,23 further supporting the concept that p16 (INK4a) inactivation is one of the mechanisms through which tumor cells overcome senescence induced by mutant BRAF.

In our study, we demonstrated that p16 (INK4a) is consistently overexpressed in MA. This finding suggests that the low proliferative rate of this tumor might be attributed to BRAFV600E-induced senescence mediated by p16 (INK4a). Similar to melanocytic nevi, however, p16 (INK4a) overexpression is observed only in subsets of cells within a given tumor, suggesting that the senescence process could also be dependent on other factors. Such factors might include insulin growth factor binding protein 7 (IGFBP7), which has been implicated in melanocyte senescence induced by oncogenic BRAF.24 Interestingly, malignant melanoma cells that harbor BRAFV600E mutations manage to silence IGFBP7, suggesting an escape mechanism.

Data from both our group and others demonstrate that the BRAF V600E mutation is rarely detected in other kidney neoplasms, indicating that testing for it in SRMs could be used as a valuable tool for the diagnosis of MA, a relatively benign entity. Indeed, in a large number of specimens from different RCC histologies (clear cell, N=63; papillary, N=22; chromophobe, N=14), no BRAF mutations were found.25 Another series from the Sanger Institute tested 308 kidney cancer samples of different histological subtypes, and found 1 deletion-frameshift in the BRAF gene in 1 sample only (p.V590fs*3), which was not a missense V600E mutation.26 Another series did not show any BRAF mutations in 23 cases of Wilms tumors.27 These results are in line with our analysis of various renal tumor types, which demonstrated the presence of BRAFV600E mutation only in one papillary RCC case.

Consistent with other reports in the literature, we show that MA present as a SRM, has a female preponderance and has an excellent prognosis with no known recurrences in our series. The conundrum of SRM is gaining widespread attention and a radical treatment such as nephrectomy may not be needed. The unnecessary removal of the kidney (radical or partial nephrectomy) is associated with significant health concerns due to reduced renal function. In one study of over 1 million patients, the risk of death, cardiovascular events and hospitalization were increased with each gradual decrease in renal function.6 Radical therapy should be focused on SRMs with potentially aggressive behavior and a large number of SRMs may in fact be benign tumors or indolent cancers on pathologic examination. In one study, ~20% of all SRMs were benign.28 Renal mass biopsy could be a valuable tool in this setting. In some situations however, the diagnosis can be challenging even in the hands of expert pathologists. We suggest that in the right clinical scenario, such as in women with a hypoattenuating renal mass on CT (and no evidence of other malignancies), biopsy could be performed and whenever pathology results are dubious or inconclusive, testing for BRAFV600E mutation for MA through a simple commercially available test could be entertained. Surveillance could be encouraged in this situation, saving patients from an unnecessary surgery, which is associated with potentially short- and long-term complications.

Interestingly, we also found that the 3 patients with wild-type disease were younger and had a trend towards smaller tumors. While these results need to be interpreted with caution because of the small sample size, it is possible that the acquisition of BRAF mutations and downstream activation of MAPK signaling could represent a late event in MA development. On the other hand, the fact that a wild-type MA analyzed by IHC demonstrated p-MEK and p-ERK positivity suggests that MAPK pathway activation may also play role in the pathogenesis of BRAF wild-type MA cases, where it may be sustained by genetic or epigenetic changes other than BRAFV600E mutation.

We recognize that this study has a few limitations, including the analysis of a somewhat limited number of patients and the retrospective nature of the report. Nevertheless, this remains one of the largest reports of this rare tumor.

In conclusion, we provide for the first time evidence that the BRAFV600E mutation is present in 90% of metanephric adenomas of the kidney, suggesting a potential diagnostic tool for this rare kidney tumor that often presents diagnostic challenges. Similar to the case of melanocytic nevi, our data suggest that BRAF V600E mutation induces senescence and that this process is mediated by p16 (INK4a), further supporting an interplay between these two pathways in oncogenesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Wanling Xie (DFCI) for assistance with statistical analysis; Paul Van Hummelen, PhD and Laura MacConaill, PhD (Center for Cancer Genome Discovery at DFCI) for helpful discussion of genotyping results; and Dimity Zepf and Jacqueline Bruce (Center for Advanced Molecular Diagnostics at BWH) for technical assistance with BRAF pyrosequencing. This work was supported by a Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Kidney Cancer SPORE Director’s Choice Award to SS and TC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amin MB, Amin MB, Tamboli P, et al. Prognostic impact of histologic subtyping of adult renal epithelial neoplasms: an experience of 405 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26(3):281–291. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snyder ME, Bach A, Kattan MW, Raj GV, Reuter VE, Russo P. Incidence of benign lesions for clinically localized renal masses smaller than 7 cm in radiological diameter: influence of sex. J Urol. 2006;176(6 Pt 1):2391–2395. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.013. discussion 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastide C, Rambeaud JJ, Bach AM, Russo P. Metanephric adenoma of the kidney: clinical and radiological study of nine cases. BJU Int. 2009;103(11):1544–1548. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renshaw AA, Freyer DR, Hammers YA. Metastatic metanephric adenoma in a child. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(4):570–574. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200004000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paner GP, Turk TM, Clark JI, Lindgren V, Picken MM. Passive seeding in metanephric adenoma: a review of pseudometastatic lesions in perinephric lymph nodes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129(10):1317–1321. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-1317-PSIMAA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Algaba F. Renal adenomas: pathological differential diagnosis with malignant tumors. Adv Urol. 2008:974848. doi: 10.1155/2008/974848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azabdaftari G, Alroy J, Banner BF, Ucci A, Bhan I, Cheville JC. S100 protein expression distinguishes metanephric adenomas from other renal neoplasms. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204(10):719–723. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan CC, Epstein JI. Detection of chromosome copy number alterations in metanephric adenomas by array comparative genomic hybridization. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(12):1634–1640. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szponar A, Yusenko MV, Kovacs G. High-resolution array CGH of metanephric adenomas: lack of DNA copy number changes. Histopathology. 2010;56(2):212–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacConaill LE, Campbell CD, Kehoe SM, et al. Profiling critical cancer gene mutations in clinical tumor samples. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas RK, Baker AC, Debiasi RM, et al. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39(3):347–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116(11):1919–1923. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schindler G, Capper D, Meyer J, et al. Analysis of BRAF V600E mutation in 1,320 nervous system tumors reveals high mutation frequencies in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, ganglioglioma and extra-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121(3):397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu J, Rosenbaum E, Begum S, Westra WH. Distribution of BRAF T1799A(V600E) mutations across various types of benign nevi: implications for melanocytic tumorigenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29(6):534–537. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181584950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(20):2135–2147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiacci E, Trifonov V, Schiavoni G, et al. BRAF mutations in hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(24):2305–2315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417(6892):949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacob K, Quang-Khuong DA, Jones DT, et al. Genetic aberrations leading to MAPK pathway activation mediate oncogene-induced senescence in sporadic pilocytic astrocytomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(14):4650–4660. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raabe EH, Lim KS, Kim JM, et al. BRAF activation induces transformation and then senescence in human neural stem cells: a pilocytic astrocytoma model. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(11):3590–3599. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Soengas MS, et al. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005;436(7051):720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature03890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Straume O, Smeds J, Kumar R, Hemminki K, Akslen LA. Significant impact of promoter hypermethylation and the 540 C>T polymorphism of CDKN2A in cutaneous melanoma of the vertical growth phase. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(1):229–237. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64174-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wajapeyee N, Serra RW, Zhu X, Mahalingam M, Green MR. Oncogenic BRAF induces senescence and apoptosis through pathways mediated by the secreted protein IGFBP7. Cell. 2008;132(3):363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gattenlohner S, Etschmann B, Riedmiller H, Muller-Hermelink HK. Lack of KRAS and BRAF mutation in renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2009;55(6):1490–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. [accessed February 1, 2012]; http://www.sanger.ac.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miao J, Kusafuka T, Fukuzawa M. Hotspot mutations of BRAF gene are not associated with pediatric solid neoplasms. Oncol Rep. 2004;12(6):1269–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frank I, Blute ML, Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Weaver AL, Zincke H. Solid renal tumors: an analysis of pathological features related to tumor size. J Urol. 2003;170(6 Pt 1):2217–2220. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000095475.12515.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.