Abstract

Background

Employer support is important for mothers, as returning to work is a common reason for discontinuing breastfeeding. This article explores support available to breastfeeding employees of hospitals that provide maternity care.

Objectives

This study aimed to describe the prevalence of 7 different types of worksite support and changes in these supports available to breastfeeding employees at hospitals that provide maternity care from 2007 to 2011.

Methods

Hospital data from the 2007, 2009, and 2011 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Survey on Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC) were analyzed. Survey respondents were asked if the hospital provides any of the following supports to hospital staff: (1) a designated room to express milk, (2) on-site child care, (3) an electric breast pump, (4) permission to use existing work breaks to express milk, (5) a breastfeeding support group, (6) lactation consultant/ specialist available for consult, and (7) paid maternity leave other than accrued vacation or sick leave. This study was exempt from ethical approval because it was a secondary analysis of a publicly available dataset.

Results

Of the 7 worksite supports in hospitals measured, 6 increased and 1 decreased from 2007 to 2011. Across all survey years, more than 70% of hospitals provided supports for expressing breast milk, whereas less than 15% provided direct access to the breastfeeding child through on-site child care, and less than 35% offered paid maternity leave. Results differed by region and hospital size and type. In 2011, only 2% of maternity hospitals provided all 7 worksite supports; 40% provided 5 or more.

Conclusion

The majority of maternity care hospitals (> 70%) offer breastfeeding supports that allow employees to express breast milk. Supports that provide direct access to the breastfeeding child, which would allow employees to breastfeed at the breast, and access to breastfeeding support groups are much less frequent than other supports, suggesting opportunities for improvement.

Keywords: breastfeeding, employees, hospitals, lactation program, Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care, worksite

Well Established

Breastfeeding is recommended as the best source of nutrition for infants and is an important public health issue. Hospitals’ crucial role in supporting women who give birth in their facilities to begin breastfeeding has long been recognized. However, hospitals also play an important role in providing support to their employees so they may continue breastfeeding when they return to work.

Newly Expressed

This article looks at 7 different types of worksite support and changes in these supports available to breastfeeding employees from 2007 to 2011 at hospitals that provide maternity care. Data are from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2007, 2009, and 2011 Survey on Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care.

Background

Breastfeeding is recommended as the best source of nutrition for infants and is an important public health issue.1 The crucial role that maternity hospitals play in supporting women who give birth in their facilities to begin breastfeeding has long been recognized.2 However, in addition to supporting their patients, hospitals also play an important role in providing support to their employees so they may continue breast-feeding when they return to work. There are over 2500 maternity care hospitals in the United States. Hospitals employ over 6.2 million full- and part-time salary and wage workers, 77% of whom are women.3

Many working mothers face significant barriers to breast-feeding, including limited maternity leave, few breaks or private places to breastfeed or express milk, lack of adequate refrigerator space to store expressed milk, concern for job security in requiring additional accommodations, and minimal peer or professional support in how to overcome some of these barriers.4 Much of what is known about breastfeeding rates among workers within the health care sector comes from data collected among physicians and shows that while new mothers who are physicians may have high breastfeeding initiation rates, they often do not meet personal breastfeeding goals.5 Returning to work is a common barrier to breastfeeding in general, and studies among physicians cite returning to work as the most common reason for discontinuing breastfeeding.6–8

Personal and spousal breastfeeding experiences are associated with how physicians counsel and advocate for breast-feeding supports for their patients.9,10 There is little information about how the breastfeeding experience of non-physician hospital employees affects interactions with breastfeeding patients. Ensuring sufficient breastfeeding support among health care workers is critical for helping them achieve their own breastfeeding goals and may even impact the support they offer breastfeeding patients.

Methods

To better understand the current level of breastfeeding support for hospital employees, we analyzed data from the Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC) survey. mPINC is a national census of maternity care facilities in the United States conducted every 2 years, beginning in 2007, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Every hospital and birth center in the United States that provides maternity services is asked to identify the person most knowledgeable about the facility’s maternity care practices to complete the mPINC survey. Using data from the 2007, 2009, and 2011 mPINC surveys (n = 2672–2742; response rates, 82%–83%), we examined 7 indicators of worksite breastfeeding support for hospital employees. As freestanding birth centers are often small with varying mechanisms for employing and supporting staff, they were excluded from this analysis (n = 118–143). Respondents were asked if the hospital provides any of the following to hospital staff who are also mothers: (1) a designated room to express milk, (2) on-site child care, (3) an electric breast pump, (4) permission to use existing work breaks to express milk, (5) a breastfeeding support group, (6) lactation consultant/specialist available for consult, and (7) paid maternity leave other than accrued vacation or sick leave. Each indicator is consistent with action steps outlined in The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding.4 Response options for each indicator of support were yes or no. Hospitals with missing values for specific supports were excluded from the analysis for that support (n = 105–261). We described the prevalence of hospitals with each of the indicators of worksite breastfeeding support by survey year as well as by facility type (government, nonprofit, private, and military hospitals), hospital size measured by number of annual births, and region. Because mPINC is a census, the prevalences presented are not subject to sampling error and so no statistical tests were performed.

Results

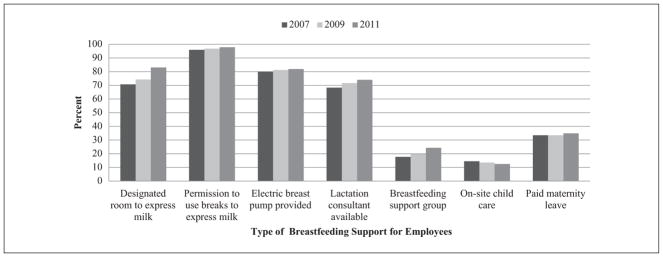

Of the 7 worksite supports in hospitals measured from 2007 to 2011, 6 increased; however, on-site child care decreased overall (see Figure 1). Larger hospitals were more likely to provide breastfeeding support for employees than smaller facilities across all 3 years of data. Higher percentages of both nonprofit and military hospitals provided most types of breastfeeding support to employees compared to private hospitals and government hospitals. For most indicators, government hospitals were the least likely to provide breastfeeding supports to employees. There were also regional differences; with the exception of providing a breast pump or a room to express milk, the Southwest had the lowest percentage of hospitals providing breastfeeding support to employees. On the other hand, with the exception of providing on-site child care, the Northeast was the most likely to provide breastfeeding employees any of the 7 supports (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Employee Supports by Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC) by Survey Year.

Table 1.

Indicators of Worksite Breastfeeding Support for Hospital Employees—Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC) 2007, 2009, and 2011.a

| N | Designated Room to Express Milk |

Permission to Use Breaks to Express Milk |

Electric Breast Pump Provided |

Lactation Consultant Available |

Breastfeeding Support Group |

On-Site Child Care |

Paid Maternity Leave |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | ||

| All | 2633–2701 | 70.7 | 74.3 | 83.0 | 95.9 | 96.8 | 97.8 | 80.0 | 81.2 | 81.9 | 68.3 | 71.6 | 74.0 | 17.7 | 19.8 | 24.3 | 14.5 | 13.5 | 12.5 | 33.5 | 33.5 | 34.9 |

| Type of facility | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government hospital | 519–525 | 60.2 | 63.5 | 75.9 | 93.2 | 94.8 | 97.3 | 69.9 | 68.9 | 70.4 | 57.8 | 59.9 | 61.4 | 11.6 | 14.6 | 16.4 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 8.7 | 30.9 | 27.8 | 30.5 |

| Nonprofit hospital | 1669–1691 | 74.8 | 78.7 | 85.6 | 96.8 | 97.8 | 98.3 | 83.7 | 84.8 | 85.6 | 73.3 | 77.1 | 79.4 | 19.9 | 22.8 | 27.0 | 17.9 | 17.1 | 14.7 | 34.6 | 36.8 | 37.1 |

| Private hospital | 303–342 | 65.0 | 68.8 | 81.0 | 95.4 | 94.8 | 95.6 | 76.5 | 82.5 | 82.1 | 58.2 | 62.1 | 66.3 | 15.4 | 12.8 | 23.2 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 6.6 | 29.0 | 27.3 | 29.3 |

| Military hospital | 18–26 | 84.6 | 76.2 | 77.8 | 96.2 | 100 | 100 | 92.3 | 90.5 | 72.2 | 80.0 | 71.4 | 72.2 | 26.9 | 23.8 | 22.2 | 7.7 | 14.3 | 22.2 | 69.2 | 85.7 | 66.7 |

| Size of facility, No. of annual births | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0–249 | 585–612 | 52.8 | 53.4 | 67.0 | 91.8 | 93.8 | 95.5 | 52.9 | 54.8 | 55.1 | 45.2 | 47.6 | 51.8 | 7.1 | 11.3 | 12.6 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 3.3 | 30.4 | 31.7 | 30.5 |

| 250–499 | 428–453 | 62.4 | 69.0 | 77.5 | 94.6 | 95.9 | 97.5 | 77.5 | 78.8 | 78.5 | 57.3 | 59.5 | 61.1 | 14.5 | 14.6 | 16.6 | 6.9 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 29.7 | 32.0 | 31.8 |

| 500–999 | 536–566 | 71.2 | 77.9 | 84.4 | 96.8 | 96.5 | 97.9 | 89.6 | 88.1 | 90.8 | 71.5 | 74.4 | 78.0 | 19.5 | 22.1 | 27.1 | 13.2 | 11.3 | 10.0 | 29.5 | 32.3 | 33.6 |

| 1000–1999 | 547–561 | 80.0 | 82.9 | 90.0 | 98.0 | 99.0 | 98.2 | 87.6 | 91.2 | 89.1 | 79.6 | 86.4 | 85.6 | 23.0 | 24.2 | 30.9 | 18.6 | 19.8 | 18.0 | 38.4 | 35.8 | 37.6 |

| 2000–4999 | 429–461 | 85.3 | 86.7 | 92.8 | 98.4 | 98.2 | 99.1 | 91.6 | 90.4 | 91.1 | 86.2 | 86.5 | 87.8 | 21.9 | 25.6 | 30.7 | 28.5 | 25.2 | 22.1 | 38.0 | 36.9 | 38.5 |

| 5000 or more | 57–64 | 82.8 | 84.2 | 94.7 | 95.2 | 100 | 100 | 90.6 | 91.2 | 94.7 | 81.0 | 91.2 | 87.7 | 28.6 | 25.0 | 39.3 | 31.8 | 29.6 | 35.1 | 42.9 | 50.9 | 52.6 |

| Region | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western | 388–409 | 71.1 | 72.6 | 79.7 | 96.7 | 94.9 | 97.6 | 80.3 | 80.5 | 79.4 | 66.8 | 69.0 | 72.2 | 19.6 | 20.4 | 23.9 | 12.1 | 11.6 | 11.7 | 47.3 | 50.0 | 47.6 |

| Southwest | 300–338 | 66.3 | 65.7 | 80.5 | 92.7 | 96.2 | 95.9 | 72.4 | 72.9 | 77.0 | 54.5 | 56.0 | 62.7 | 11.1 | 10.5 | 14.6 | 9.4 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 23.6 | 21.0 | 24.3 |

| Southeast | 412–433 | 65.6 | 70.2 | 79.6 | 96.3 | 95.4 | 97.2 | 78.7 | 83.2 | 83.9 | 66.2 | 70.2 | 71.3 | 17.1 | 15.8 | 19.4 | 14.8 | 13.5 | 19.0 | 28.5 | 25.5 | 24.5 |

| Northeast | 223–236 | 77.1 | 84.3 | 90.6 | 98.7 | 99.6 | 99.2 | 91.9 | 92.0 | 94.9 | 87.4 | 86.5 | 90.1 | 29.7 | 34.2 | 40.5 | 19.6 | 16.8 | 10.4 | 31.8 | 31.6 | 34.4 |

| Mountain plains | 385–393 | 65.7 | 70.1 | 78.6 | 93.6 | 97.4 | 98.5 | 71.5 | 72.6 | 73.3 | 58.0 | 65.1 | 68.9 | 11.9 | 17.1 | 23.0 | 13.1 | 14.1 | 16.1 | 29.5 | 30.0 | 32.3 |

| Midwest | 528–531 | 78.3 | 80.7 | 88.0 | 97.4 | 97.7 | 98.3 | 84.8 | 85.7 | 83.6 | 79.2 | 79.8 | 80.8 | 19.8 | 20.6 | 25.7 | 14.5 | 13.7 | 19.0 | 37.5 | 37.9 | 40.6 |

| Mid-Atlantic | 243–260 | 70.0 | 78.1 | 86.4 | 95.8 | 97.6 | 97.9 | 83.5 | 83.4 | 87.6 | 66.9 | 76.3 | 74.8 | 17.7 | 26.1 | 30.7 | 20.9 | 20.6 | 15.5 | 31.5 | 41.2 | 38.9 |

Bolded numbers indicate the highest prevalence across the 3 survey years. Sample size numbers range across years and questions.

Across all survey years, hospitals were more likely to support employees to be able to express breast milk (ie, designated room, provide electric pump, permission to use break time to express milk) than to have policies or environments that support direct access to their breastfeeding children during the day (ie, on-site child care or paid maternity leave). Supports that provide direct access to the child, which may facilitate mothers being able to feed at the breast, increased little or not at all from 2007 to 2011 (see Table 1).

In 2011, only 2% of maternity hospitals in the United States provided all 7 of the worksite supports for breastfeeding employees measured on the mPINC survey, and about 40% of hospitals provided 5 or more supports (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of Hospitals by Number of Employee Supports in Place for Breastfeeding, 2011.

| No. of Supports | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 19 | 0.8 |

| 1 | 92 | 3.7 |

| 2 | 196 | 7.9 |

| 3 | 424 | 17.1 |

| 4 | 768 | 31.1 |

| 5 | 661 | 26.7 |

| 6 | 257 | 10.4 |

| 7 | 56 | 2.3 |

Discussion

Overall, we found that nearly all birthing hospitals in the United States allowed employees to use break time to express milk, and ~ 80% (2011) provided a place to express milk and an electric breast pump.

Birthing hospitals were less likely to allow women direct access to their children during the workday or access to professional support or a breastfeeding support group. Our analysis reports data only from birthing hospitals, which may not reflect the level of breastfeeding support that other, nonbirthing facilities may offer. The limited data that are available regarding breastfeeding support for employees in other sectors of the workforce suggest that birthing hospitals of all sizes and types are providing more breastfeeding support than the general workforce. According to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) benefits report, which summarizes an annual survey of its members, in 2011 (18% response rate, n = 600), 28% of SHRM member employers provided an on-site lactation room, 16% provided paid maternity leave, and only 5% provided lactation consulting and education.11

Although our data indicate that the hospital supports for many indicators are high, our data do not document whether employees can take advantage of these supports. The hospital sector workforce is large and diverse and includes physicians, nurses, and other allied health professionals, as well as administrative staff, nurses’ aides, orderlies, attendants, and more.12 Aside from the literature related to physicians, there are limited data on specific obstacles that workers in this field face when it comes to meeting their personal infant feeding goals. It is known that hospital jobs are often demanding and the workload great—conditions which, if not handled skillfully, may make it hard for workers to take advantage of the breastfeeding supports in place.5,13,14 Having a written policy is an important step but can be insufficient unless the worksite, work atmosphere, and work culture allow employees to feel that they have the time and support to take advantage of existing policies that may help them achieve their infant feeding goals.5,15–17 Supporting mothers employed in this sector to meet their personal breastfeeding goals may have the added benefit of these workers better supporting the breastfeeding patients with whom they interact.5,10

It is clear that the majority of maternity care hospitals provided time and space for employees to be able to express breast milk even before these (ie, designated room, permission to use break time to express milk) measures were protected under Section 4207 of the Affordable Care Act that amended the Fair Labor Standards Act to require that certain employers provide “a reasonable break time for an employee to express breast milk for her nursing child for one year after the child’s birth each time such employee has need to express the milk.” Employers are also required to provide a place, other than a bathroom, that is shielded from view and free from intrusion from coworkers and the public, which may be used by an employee to express breast milk.18 Non-office settings like hospitals may warrant special considerations and innovative solutions when planning for and providing breast-feeding support to working mothers. For example, descriptive and qualitative data collected by Sattari et al5 from a survey of 50 physicians found that mothers in surgical specialties and procedure-based subspecialties reported the unavailability of lactation rooms close to operating rooms as a barrier to breast-feeding.5 Experiences like these are, in part, the reason that The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding highlights the importance of developing “innovative solutions to the obstacles to breastfeeding that women face when returning to work in non-office settings.”4

A limitation of these data is that mPINC is a self-reported survey filled out by a key informant at each hospital. Although a standard protocol is followed to identify the key informant, the responses may not accurately represent all practices. The findings are applicable to hospitals that provide maternity care and may not be representative of other hospitals.

Conclusion

The majority of maternity care hospitals in the United States offer breastfeeding supports that allow mothers to express breast milk. Supports that would allow employees access to their children during the workday and access to a breastfeeding support group are less frequent than other supports and could be bolstered.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics Section of Breastfeeding. . Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827–e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. [Accessed October 30, 2012];Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/bfhi/en/

- 3.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Accessed October 30, 2012];Women in the labor force: a data-book. http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlftable14-2010.htm. Published 2010.

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sattari M, Levine D, Bertram A, Serwint J. Breastfeeding intentions of female physicians. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5(6):297–302. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arthur C, Saenz R, Replogle W. The employment-related breastfeeding decisions of physician mothers. J Miss State Med Assoc. 2003;44(12):383–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandal B, Roe BE, Fein SB. The differential effects of full-time and part-time work status on breastfeeding. Health Policy. 2010;97(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan AS, Zhou W, Arensberg MB. The effect of employment status on breastfeeding in the United States. Womens Health Issues. 2006;16(5):243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freed GL, Clark SJ, Curtis P, Sorenson JR. Breast-feeding education and practice in family medicine. J Fam Pract. 1995;40(3):263–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freed GL, Clark SJ, Sorenson J, Lohr JA, Cefalo R, Curtis P. National assessment of physicians’ breast-feeding knowledge, attitudes, training, and experience. JAMA. 1995;273(6):472–476. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520300046035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Society for Human Resource Management. 2011 Employee Benefits: Examining Employee Benefits amidst Uncertainty. Alexandria, VA: Society for Human Resource Management; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Accessed October 30, 2012];Industries at a glance: health care and social assistance. http://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag62.htm#workforce.

- 13.McHugh M, Kutney Lee A, Cimiotti J, Sloane D, Aiken L. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff. 2011;30(2):202–210. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller NH, Miller DJ, Chism M. Breastfeeding practices among resident physicians. Pediatrics. 1996;98(3):434–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batt R, Valcour PM. Human resources practices as predictors of work-family outcomes and employee turnover. Industrial Relations. 2003;42(2):189–220. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blair-Loy M, Wharton AS. Employees’ use of work–family policies and the workplace social context. Social Forces. 2002;80(3):813–845. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson CA, Beauvais LL, Lyness KS. When work–family benefits are not enough: the influence of work–family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work–family conflict. J Vocat Behav. 1999;54(3):392–415. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub L No. 111–148, §4207 (2010).