Abstract

Few studies have investigated school-based, positive development for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer (LGBQ) youth, despite knowledge of their heightened negative school experiences compared to heterosexual youth (e.g., school victimization). This study examines associations among participation in Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA)–related social justice activities, GSA presence, and GSA membership with victimization based on sexual orientation and school-based well-being (i.e., school safety, school belongingness, grade point average [GPA]) and future plans to vote. Using data from the Preventing School Harassment Study, a survey of 230 LGBQ students in 7th through 12th grades, the study finds that participation in GSA-related social justice activities and the presence of a GSA are positively associated with school belongingness and GPA. GSA membership is also positively associated with school belongingness. However, moderation analyses suggest that the positive benefits of GSA-related social justice involvement and the presence of a GSA dissipate at high levels of school victimization. Implications for schools are discussed.

Keywords: social justice, gay—straight alliances, victimization, academic achievement, LGBT issues

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer (LGBQ) and sexual minority (e.g., individuals who report same-sex attractions) youth are known to be a population that is disproportionally at risk for a myriad of poor health (e.g., Institute of Medicine, 2011) and academic outcomes (e.g., Russell, Seif, & Truong, 2001). In the past two decades, researchers have theorized and empirically documented that this heightened risk is partially due to experiences of stigma and discrimination (e.g., Meyer, 2003). Stigma and discrimination toward LGBQ individuals can be experienced at all levels of an individual’s ecological system, spanning from the microsystem (e.g., families or schools; Kosciw, Greytak, Diaz, & Bartkiewicz, 2010; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009) to the macrosystem (e.g., political systems or cultural values and beliefs; Russell, Bohan, McCarroll, & Smith, 2010). Research has documented that schools are a primary setting where LGBQ youth experience homophobia and bias-motivated violence (e.g., Kosciw et al., 2010). Nonetheless, research on school experiences of LGBQ youth has largely focused on experiences of victimization, and only a few studies have explored the positive developmental experiences of LGBQ youth in this context.

One major exception to the sole focus on negative school experiences of LGBQ youth is the research on Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs). GSAs are school-based, student-led clubs that provide safe spaces for LGBQ youth and their straight allies (e.g., Goodenow, Szalacha, & Westheimer, 2006; O’Shaughnessy, Russell, Heck, Calhoun, & Laub, 2004). GSAs emerged in the late 1980s in California (e.g., Project 10) and Massachusetts (for review, see Griffin & Ouellett, 2003). According to the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN), as of 2011 there are more than 4,000 GSAs registered in the United States (for more information, see www.glsen.org). GSAs are dispersed across the United States; however, research has documented that the social context of a community has an impact on the adoption of a GSA in the school (Fetner & Kush, 2008). Specifically, Fetner and Kush found that GSAs are more likely to emerge in schools that are located in the following settings: urban/suburban, liberal or progressive political settings, larger schools, and in wealthier neighborhoods. Although widely a U.S.-based phenomenon, GSAs have also begun to form in other countries (e.g., Mexico; Macgillivray, 2005).

Research has documented several protective benefits of the presence of GSAs for LGBQ youth. For example, the presence of a GSA is associated with less victimization based on sexual orientation (Kosciw et al., 2010), less suicidality (Goodenow et al., 2006), and higher levels of self-reported safety at school (e.g., O’Shaughnessy et al., 2004; Szalacha, 2003; Walls, Kane, & Wisneski, 2010).

Beyond the presence of a GSA, research has also documented that youth participation in GSAs is associated with a myriad of positive developmental outcomes, such as higher academic achievement and greater personal comfort with one’s sexual orientation (Lee, 2002). GSAs also offer the potential for student participants to feel empowered and to enact personal agency (Russell, Muraco, Subramaniam, & Laub, 2009). This finding is parallel to research from the general adolescent literature that suggests that adolescents who are engaged in student-directed advocacy organizations and activities at school report greater levels of self-efficacy and are more involved in their greater community (e.g., Flanagan, 2004). The research findings on associations among GSA participation and positive outcomes, however, have not been consistent. For example, Walls and colleagues (2010) found a significant positive association between GSA membership and grade point average (GPA) but did not find significant associations between GSA membership and school safety, school absence, weapon carrying, or school victimization.

Although research has documented the associations among GSA presence and participation with mental health and academic outcomes, the associations between involvement in specific activities related to GSA membership and mental health and academic outcomes have not been explored. For instance, the links among engagement in GSA-related social justice activities (e.g., attending a political rally related to LGBQ issues) and health and academic outcomes have not been examined. Yet previous research has documented that GSA members frequently engage in these types of activities with their GSAs (Russell, Toomey, Crockett, & Laub, 2010).

In this study, we explored the associations between involvement in GSA-related social justice activities and academic and civic outcomes for LGBQ youth. Secondary to the primary goal of this study, we also examined the direct associations between GSA presence and membership and our outcomes to continue to build the limited literature that exists. We then examined whether or not GSA presence, membership, or social justice engagement had the power to buffer the associations between school victimization based on sexual orientation and academic and civic outcomes for LGBQ youth. This research is critical for documenting the importance of the availability of GSAs and social justice activities for LGBQ youth as well as for understanding potential pathways to positive youth development for this vulnerable population. In the following sections, we first review the literature on youth involvement in social justice activities and the limited studies that examine LGBQ youth in this context. We then briefly review the literature on LGBQ youth experiences in schools, including a specific focus on GSAs. We end with analyses from the Preventing School Harassment Study that explore the associations among involvement in GSA-related social justice activities, GSA presence, GSA membership, school victimization based on sexual orientation, and academic and civic outcomes for LGBQ youth.

Social Justice Participation by Youth

Social justice activities are pathways for youth to become involved in the civic and educational institutions that affect their lives. Conceptually, adolescent engagement in social justice activities should be linked with positive youth development and future civic participation because this type of engagement should build adolescent capacity to develop pride in one’s identity, develop authenticity and empowerment, and create change in adult-dominated power structures (e.g., Ginwright & Cammarota, 2002; Ginwright & James, 2002). However, there is limited empirical information available about the associations among involvement in social justice activities and academic outcomes and future civic engagement (e.g., voting).

In a conceptual model of youth engagement, Flanagan (2004) suggests that youth participation in structured activities allows for the development of a collective identity. Similarly, Meyer (2003) suggests that collective identities are one way that LGBQ individuals cope with social stigma and homophobic experiences. Thus, it is plausible that LGBQ youth involvement in GSA-related social justice activities will help LGBQ students to build a sense of collective identity, which should in turn help them cope with stigma and discrimination, such as school victimization based on sexual orientation. Furthermore, participation in these types of activities may be related to future civic engagement, such as voting or future participation in LGBQ-related social justice activities. For instance, researchers have found significant associations between adolescent activity involvement (e.g., school-based extracurricular activities) and young adult civic engagement (e.g., voting; McFarland & Thomas, 2006; Zaff, Malanchuk, & Eccles, 2008). In one study of LGBQ youth, Russell and colleagues (2010) documented that youth who were involved in social justice activities through their GSAs also reported plans for future social justice and civic engagement (e.g., 62% planned to vote, and 48% planned to contact their legislator). Nonetheless, that study only included students who were involved in their GSAs and who were active participants in GSA-related social justice activities; there was no comparison group available to examine the unique associations between GSA presence, GSA membership, and social justice involvement.

The School Environment for LGBQ Youth

There is little disagreement that LGBQ youth experience alarmingly high rates of school victimization. Several studies of LGBQ youth have documented high levels of school victimization (e.g., Kosciw et al., 2010). This research is further validated by other findings that homophobic attitudes and values are prevalent in adolescent peer groups (Horn & Nucci, 2006; Poteat, Espelage, & Green, 2007).

Findings also suggest that LGBQ students experience lower levels of school safety than their heterosexual peers (e.g., O’Shaughnessy et al., 2004), and in studies of LGBQ youth, researchers have found that nearly 60% of students report feeling unsafe in their schools because of their sexual orientation and 40% because of their gender expression (e.g., Kosciw et al., 2010). Research has also documented that LGBQ youth who experience high amounts of victimization based on sexual orientation also report lower GPAs and fewer feelings of school belongingness (e.g., Kosciw et al., 2010). Using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, researchers documented that same-sex-attracted youth who experienced school harassment reported lower GPAs (Russell et al., 2001). LGBQ students also tend to report lower levels of school belonging than heterosexual students (e.g., Murdock & Bolch, 2005). Furthermore, harassment based on sexual orientation is directly related to lower levels of school belongingness for LGB students (e.g., Diaz, Kosciw, & Greytak, 2010).

To date, little empirical information is available that documents potential pathways for LGBQ youth to overcome negative school experiences, such as victimization based on sexual orientation. Research that does examine positive development for LGBQ youth is largely based on five school-level policies and safe school strategies: sexual orientation and gender expression–inclusive antiharassment policies, teacher intervention in bias-motivated harassment, student access to LGBQ–inclusive information and support, LGBQ-inclusive curriculum, and GSAs in schools (e.g., Griffin & Ouellett, 2003; O’Shaughnessy et al., 2004). These policies and safe school strategies are positively associated with school safety and less bias-motivated harassment for LGBQ youth (e.g., O’Shaughnessy et al., 2004). Yet with the exception of GSAs, these strategies are all implemented and enforced at the school or district level. GSAs, on the other hand, are usually created by students (Griffin & Ouellett, 2003). Student engagement to help create safer school climates, whether that includes lobbying for these safe school policies and strategies or creating a GSA, is likely to also have positive influences on individual student school-based outcomes and might also be capable of buffering the negative link between victimization and well-being.

The presence of a GSA is associated with a myriad of positive student outcomes (e.g., Goodenow et al., 2006; Kosciw et al., 2010; O’Shaughnessy et al., 2004; Szalacha, 2003; Walls et al., 2010). Furthermore, membership and involvement in GSAs is associated with several positive outcomes, as well. For example, GSA membership is associated with greater self-efficacy and more openness about one’s sexual orientation to others (e.g., Kosciw et al., 2010; Russell et al., 2009). In fact, it may be the case that the associations between school victimization based on sexual orientation and school-based outcomes differ for students based on whether their school has a GSA or student membership in that GSA. To date, we are not aware of any study that has explored the potential for GSA presence or membership to moderate the associations among victimization based on sexual orientation and school-based outcomes.

Current Study

The primary goal of this study is to examine the associations between LGBQ youth involvement in GSA-related social justice activities and their experiences of school victimization based on sexual orientation, a myriad of school outcomes, and future plans to vote. Secondary to this study, but an important addition to the literature, this study will also examine these associations for GSA presence and GSA membership. To accomplish these goals, this study will test two main research questions:

Research Question 1: What are the direct associations between participation in GSA-related social justice activities and school safety, school belongingness, GPA, and future plans to vote for LGBQ youth? Furthermore, what are the direct associations between GSA presence and membership and school safety, belongingness, GPA, and future plans to vote?

Given the novel exploration of the associations between participation in GSA-related social justice activities and our outcomes, we had no concrete hypotheses. We did, however, expect that the presence of a GSA would be positively associated with our key outcomes given robust similar findings in the literature (e.g., Walls et al., 2010). Finally, we did not have any concrete hypotheses regarding the associations between GSA membership and our outcomes given inconsistent findings in the previous literature (e.g., Russell et al., 2009; Walls et al., 2010).

Research Question 2: Does participation in GSA-related social justice activities moderate the associations among school victimization based on sexual orientation and school-based outcomes and future plans to vote for LGBQ youth? Furthermore, does the presence of a GSA or membership in a GSA moderate these associations?

Given the exploratory and novel nature of these research questions, we did not have concrete hypotheses.

Method

Sample and Procedures

We used data from the Preventing School Harassment (PSH) Study, a survey designed to explore student experiences with bias-motivated school harassment, school climate, school policies and practices, and academic outcomes (O’Shaughnessy et al., 2004). The target population for the study included lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer (LGBQ), and transgender youth and their straight allies. Participants were recruited through high school Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs), LGBQ community–based youth groups, and LGBQ community centers in California. The PSH survey was administered in the fall of 2008 and included more than 1,500 California-based LGBQ and straight middle and high school students. The survey was administered in both paper and online formats.

The analytic sample for this study was limited to the 230 LGBQ-identified youth who resided in California and who were enrolled in middle or high school. Students included in this subsample were located in 83 different California-based middle and high schools, with a range of 1 to 28 students per school. Of the 230 youth, 58.70% identified as female, 35.65% as male, and 5.65% as transgender/genderqueer. The sample was ethnically diverse: 47.39% were White, non-Latino/a; 21.74% were Latino/a; 19.13% were multiethnic/racial; 6.09% were Black, non-Latino/a; and 5.65% were Asian, non-Latino/a. Students were in Grades 7 through 12 (M = 10.51, SD = 1.19) and were ages 12 to 19 years (M = 15.69, SD = 1.39).

Measures

GSA presence, GSA membership, and social justice involvement

Participants responded to four items about their involvement in school-based, LGBQ student–led clubs and social justice activities. First, participants reported whether or not their school had a Gay-Straight Alliance, Project 10, or similar club (0 = no, 1 = yes). As a follow-up to that question, participants were asked if they were or have been a member of that club (0 = no, 1 = yes). All participants were then asked three questions about involvement in GSA-related social justice activities. The three items included: “Wrote an email or letter to your legislator about LGBTQ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer] issues,” “Attended LGBTQ political rallies or marches,” and “Visited or called your legislative representatives to discuss LGBTQ issues” (0 = no, 1 = yes). A sum score was created to examine overall involvement in GSA-related social justice activities (M = 0.60, SD = 0.89).

Experience of school victimization based on sexual orientation

The California Healthy Kids Survey measure of “harassment causes: hate-related behavior,” which includes reports of harassment based on race/ethnicity, gender, religion, sexual orientation, and disability (California Healthy Kids Survey, 2010), was utilized in the PSH survey. One item measured student experiences of school victimization based on sexual orientation: “During the past 12 months, how many times on school property were you harassed or bullied because you are gay, lesbian, or bisexual or someone thought you were?” (0 = 0 times to 3 = 4 or more times; M = 1.40, SD = 1.18).

School-based well-being

Three school-related outcomes were assessed: personal safety at school, school belongingness, and self-reported GPA. Participants responded to one item that assessed personal safety at school: “I feel safe at my school” (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree; M = 2.64, SD = 0.87). Participants responded to four items that measured feelings of school belongingness: “I feel like I am part of my school,” “I do things at my school that make a difference,” “I do interesting activities at school,” and “At school, I help decide things like class activities or rules” (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). These four items were averaged to create a scale, which demonstrated acceptable reliability (α = .81; M = 2.68, SD = 0.63). Finally, self-reported GPA was assessed by one item: “During the past 12 months, how would you describe the grades you received in school?” (0 = mostly F’s to 4 = mostly A’s; M = 2.83, SD = 1.10).

Future plans to vote

In addition to school-related outcomes, students were asked one question that assessed plans to vote in the future: “I plan to vote in the next election, as soon as I turn 18” (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree; M = 3.64, SD = 0.67). This item was adapted from a widely used scale that assesses youth expectations of future political action (Torney-Purta, Lehmann, Oswald, & Schulz, 2001).

Plan of Analysis

Prior to analysis, we used PROC MI in SAS to impute all missing data (Graham, Cumsille, & Elek-Fisk, 2003). This method was chosen in order to maximize statistical power and to minimize exclusion of participants due to missing data (Graham et al., 2003). We begin with descriptive analyses that document students’ access to and involvement in their school’s GSA. We then use multilevel modeling techniques to analyze our research questions about the association among GSA predictors and school-based outcomes because students were nested within schools. Multilevel modeling techniques are necessary because traditional regression techniques assume independence of data points, an assumption that is not met because several participants are enrolled in the same schools (Singer, 1998).

For each outcome, we examine six regression models. To address the first research question, Model 1 examines the unique association between GSA-related social justice activity participation and each respective outcome, over and above school victimization based on sexual orientation. Model 2 examines the direct association of GSA presence, over and above school victimization based on sexual orientation, with each respective outcome. The third model examines the associations among GSA membership, over and above school victimization based on sexual orientation, and each respective outcome.

To address the second research question, Model 4 explores the interaction between GSA-related social justice activity participation and school victimization on each outcome to examine whether or not participation can buffer the negative associations between victimization and our outcomes. Model 5 examines the interaction between GSA presence and victimization based on sexual orientation on the outcomes to examine whether or not GSA presence can buffer the negative associations among victimization and our outcomes. Finally, the Model 6 examines the interaction between GSA membership and school victimization on the outcomes of interest to examine whether GSA membership can buffer the negative associations among victimization and our outcomes. Simple slopes analyses were conducted to decompose all significant interaction effects (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). Because previous research (e.g., Kosciw, Greytak, & Diaz, 2009) has found that demographic characteristics (e.g., age, race, gender) are associated with the observed variables of this study (e.g., victimization based on sexual orientation), we controlled for the following four sociodemographic and methodological characteristics in each model: grade in school, paper versus online format (1 = online format), gender (females as reference group), and ethnicity (White as reference group). We controlled for study methodology because preliminary analyses revealed differences between paper and online format on key study variables.

Results

First we present descriptive information (e.g., frequencies) about and tests of demographic differences (i.e., gender, age, ethnicity, and school grade) on GSA presence, GSA membership, and GSA-related social justice activity involvement. The majority (74.35%) of participants reported that their school had a GSA or similar club. Male and female participants were more likely than transgender participants to report that their school had a GSA, χ2(df = 2) = 11.20, p < .01. There were no other significant findings that suggested demographic characteristic (i.e., ethnicity, age, school grade) differences on whether a school had a GSA or not. The majority of survey participants (67.83%) reported current or past membership in their school’s GSA. In this sample, there were no significant demographic differences associated with GSA membership.

Finally, we examined the three GSA-related social justice activity involvement items and report the nuanced findings here because of the novelty of this piece of the study. Of the 230 LGBQ youth, 32 (13.91%) reported that they wrote an e-mail or letter to their legislator about LGBTQ issues; 33 (14.35%) reported that they visited or called their legislative representative to discuss LGBTQ issues, and 74 (32.17%) reported that they attended a political rally or march that was related to LGBTQ issues. The majority of participants did not participate in any of the three activities (n = 140, 60.87%), whereas 55 (23.91%) participated in 1 activity, 21 (9.13%) participated in 2 activities, and 14 (6.09%) participated in 3 activities. Thus, the mean level of GSA-related social justice activity participation was relatively minimal (M = 0.60, SD = 0.89). The only demographic difference that emerged for social justice activity involvement was age (r = .14, p < .05), suggesting that older participants were more involved in GSA-related social justice activities than younger participants. Next, we present findings from multiple regression models that examine the associations among GSA-related social justice activity involvement, GSA presence, and GSA membership and school safety, school belongingness, GPA, and future plans for civic engagement.

Research Question 1

The first research question examined the direct associations between participation in GSA related social justice activities, as well as GSA presence and membership, and school safety, school belongingness, GPA, and future plans to vote. Involvement in GSA-related social justice activities was positively associated with school belongingness and GPA (see Table 1) but was not significantly associated with personal school safety or plans to vote in the future. Furthermore, the presence of a GSA at school was positively associated with school belongingness and GPA (see Table 1); however, presence was not associated with personal school safety or plans to vote in the future. Finally, GSA membership was only associated with school belongingness (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results From the Multilevel Regressions of GSA Predictors and School Victimization on School-based Outcomes and Future Plans to Vote.

| Safety at school

|

School belongingness

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Grade in school | .06 | .06 | .06 | .06 | .07 | .07 | .11** | .12*** | .11** | .11** | .12*** | .12** |

| Online format | −.20 | −.17 | −.20 | −.20 | −.20 | −.21 | −.08 | −.08 | −.10 | −.09 | −.09 | −.11 |

| Male | .19 | .21 | .19 | .20 | .21 | .19 | −.02 | .01 | −.02 | −.01 | .01 | −.02 |

| Transgender | −.01 | .06 | .01 | .01 | .06 | −.01 | −.09 | −.05 | −.10 | −.07 | −.05 | −.11 |

| Asian | .36 | .39 | .36 | .35 | .39 | .33 | .15 | .15 | .14 | .14 | .15 | .10 |

| Black | −.17 | −.17 | −.16 | −.17 | −.15 | −.17 | −.04 | .01 | .03 | −.05 | .01 | .02 |

| Latino | .02 | .05 | .03 | .02 | .09 | .04 | −.01 | −.01 | −.02 | −.01 | .01 | −.01 |

| Multiethnic | −.21 | −.21 | −.21 | −.21 | −.19 | −.21 | .01 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .03 | .01 |

| Victimization based on SO | −.18*** | −.18*** | −.19*** | −.18*** | −.01 | −.12 | .01 | .03 | .01 | .01 | .10 | .09 |

| GSA social justice | .01 | — | — | .01 | — | — | .20*** | — | — | .23*** | — | — |

| GSA presence | — | .17 | — | — | .17 | — | — | .35*** | — | — | .35*** | — |

| GSA membership | — | — | .03 | — | — | .01 | — | — | .27** | — | — | .25** |

| Vic. × GSA Social Justice | — | — | — | −.02 | — | — | — | — | — | −.09* | — | — |

| Vic. × GSA Presence | — | — | — | — | −.24* | — | — | — | — | — | −.10 | — |

| Vic. × GSA Membership | — | — | — | — | — | −.09 | — | — | — | — | — | −.11 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Grade point average

|

Future plans to vote

|

|||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Grade in school | −.08 | −.08 | −.08 | −.08 | −.07 | −.08 | .05 | .05 | .05 | .05 | .05 | .05 |

| Online format | −.25 | −.24 | −.27 | −.25 | −.26 | −.27 | .01 | .03 | .02 | .01 | .05 | .03 |

| Male | .12 | .16 | .12 | .13 | .15 | .12 | −.05 | −.04 | −.05 | −.04 | −.04 | −.05 |

| Transgender | −.58 | −.52 | −.59 | −.57 | −.51 | −.60 | −.03 | .01 | −.01 | −.03 | .01 | .01 |

| Asian | .27 | .30 | .27 | .27 | .29 | .26 | −.15 | −.13 | −.13 | −.15 | −.12 | −.10 |

| Black | −.25 | −.19 | −.18 | −.26 | −.17 | −.18 | .13 | .13 | .13 | .13 | .11 | .14 |

| Latino | −.16 | −.16 | −.17 | −.16 | −.12 | −.16 | −.06 | −.05 | −.05 | −.06 | −.07 | −.05 |

| Multiethnic | .01 | .02 | .01 | .01 | .04 | .01 | −.09 | −.08 | −.09 | −.09 | −.10 | −.09 |

| Victimization based on SO | −.02 | −.01 | −.03 | −.03 | .19 | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 | −.15* | −.07 |

| GSA social justice | .20* | — | — | .22** | — | — | −.01 | — | — | −.01 | — | — |

| GSA presence | — | .37* | — | — | .36* | — | — | .08 | — | — | .09 | — |

| GSA membership | — | — | .28 | — | — | .28 | — | — | .07 | — | — | .09 |

| Vic. × GSA Social Justice | — | — | — | −.06 | — | — | — | — | — | −.01 | — | — |

| Vic. × GSA Presence | — | — | — | — | −.28* | — | — | — | — | — | .20* | — |

| Vic. × GSA Membership | — | — | — | — | — | −.02 | — | — | — | — | — | .08 |

Note: Unstandardized beta coefficients from multilevel regression analyses are shown; SO = sexual orientation; GSA = Gay-Straight Alliance; Vic. = victimization based on sexual orientation.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Research Question 2

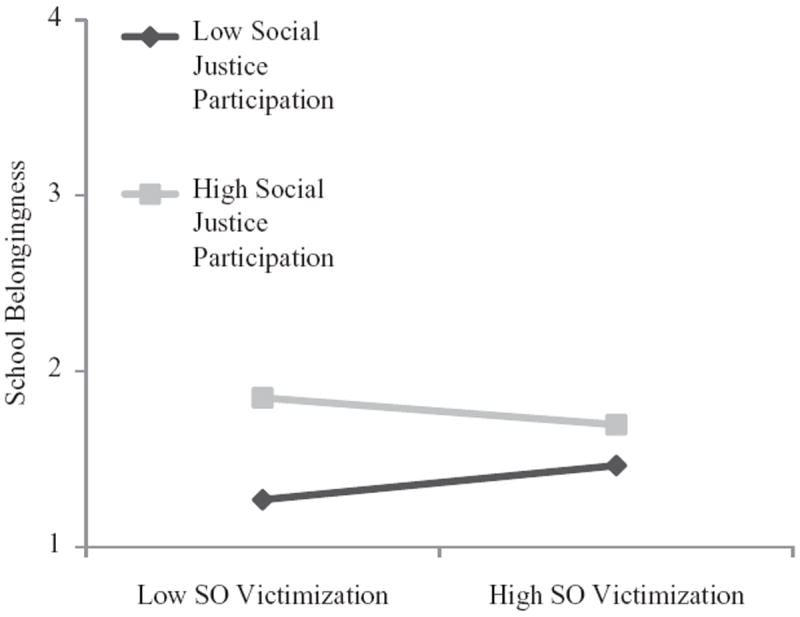

The second research question examined whether or not participation in GSA-related social justice activities, as well as GSA presence and membership, was able to buffer the associations between victimization based on sexual orientation and school-based outcomes and future plans to vote. There was a significant interaction found between participation in GSA-related social justice activities and school victimization on school belongingness. Specifically, at low levels of school victimization, students who participated at greater levels of GSA-related social justice activities reported higher levels of school belongingness than students less involved in social justice activities (see Figure 1); however, at high levels of school victimization, the benefits of social justice involvement dissipated. Simple slopes analysis revealed that neither the slope for the high-involvement group (b = −.06, t = −0.90, p = n.s.) nor the low involvement group (b = .07, t = 1.55, p = n.s.) differed from zero. These results suggest that these two groups only differ at low levels of victimization, such that those with high involvement in GSA-related social justice activities report higher levels of school belongingness compared to those with lower levels of involvement.

Figure 1.

Interaction between school victimization based on sexual orientation and Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA)–related social justice participation.

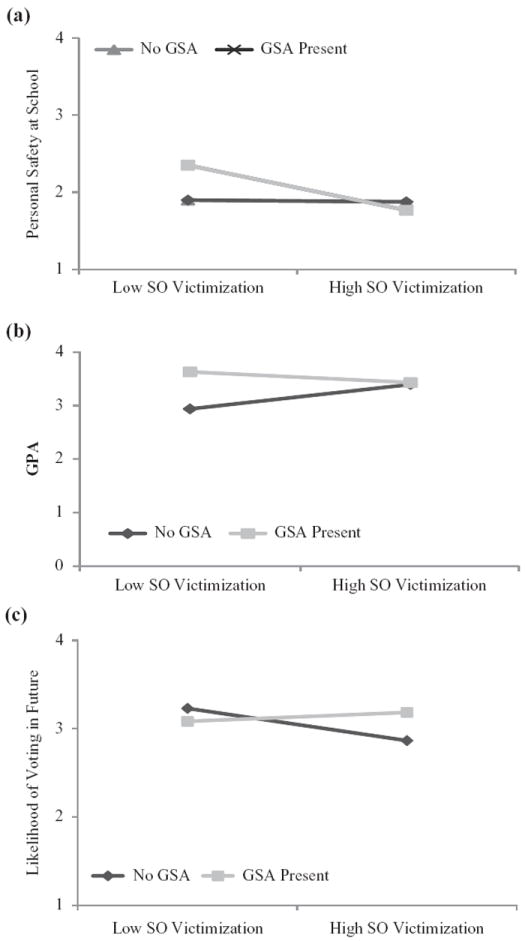

The presence of a GSA significantly moderated the associations between school victimization based on sexual orientation and three out of the four outcomes: personal school safety, GPA, and future plans to vote. As shown in Figure 2a, at low levels of school victimization, students who were aware that their school had a GSA also reported higher levels of personal safety at school. However, any potential benefit of GSA presence dissipated at high levels of school victimization. In this case, simple slopes analysis did reveal that the slope for students who reported that their school had a GSA was significant (b = −.25, t = −4.72, p < .001), whereas the slope for students without GSAs in their schools was not (b = −.03, t = −0.31, p = n.s.). These results suggest that students’ safety in school does significantly decline as victimization based on sexual orientation increases for students with GSAs. A similar interaction effect is present between GSA presence and school victimization on GPA (see Figure 2b). That is, at low levels of school victimization, students who reported the presence of a GSA also reported higher GPAs than students whose schools did not have GSAs; however, this effect also dissipated at high levels of school victimization. Simple slopes analysis revealed that neither the slope for the GSA present group (b = −.08, t = −1.17, p = n.s.) nor the GSA not present group (b = .23, t = 1.63, p = n.s.) differed from zero. These results suggest that these two groups only differ at low levels of victimization, such that those with a GSA present in their schools report higher GPAs compared to those without GSAs in their schools.

Figure 2.

Interactions between school victimization based on sexual orientation and Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA) presence: (a) Outcome: School safety, (b) Outcome: Grade point average, and (c) Outcome: Likelihood of voting in future.

A different pattern was found for the interaction predicting future plans to vote (see Figure 2c): At low levels of school victimization, there was not a difference between students whose schools had a GSA compared to those who did not report a GSA. However, for students in schools with GSAs, as levels of school victimization increased so did their plans to vote in the future. Conversely, for students in schools without GSAs, as levels of school victimization increased, plans to vote in the future decreased. Thus, it appears that the presence of a GSA buffers the negative association between school victimization on plans for future civic engagement. Simple slopes analysis revealed that neither the slope for the GSA present group (b = .04, t = 1.04, p = n.s.) nor the GSA not present group (b = −.16, t = −1.73, p = n.s.) differed from zero, suggesting that these two groups only differ at high levels of victimization such that those with a GSA present in their schools report greater intentions to vote in the future compared to those without GSAs in their schools.

GSA membership did not significantly moderate the negative association between school victimization and personal safety at school, GPA, school belongingness, or future plans to vote.

Discussion

This study adds new knowledge about the potential for positive youth development for a population that is known to be disproportionally at risk for negative academic outcomes. Specifically, we found that above and beyond the negative impact of school victimization based on sexual orientation, involvement in GSA-related social justice activities and the presence of a GSA are positively associated with higher GPAs and greater school belongingness. Similar to previous research on GSA membership (e.g., Walls et al., 2010), we did not find consistent associations among GSA membership and our school-based and civic outcomes; however, we did find a positive association between GSA membership and school belongingness. This finding is not surprising given that engagement in extracurricular activities is known to be associated with greater connectedness to school (e.g., Feldman & Matjasko, 2005). More important, these findings suggest that GSAs may be one avenue to cultivate school belongingness for LGBQ youth. Furthermore, these findings point toward social justice involvement as a promising context for positive youth development for LGBQ youth.

This is one of the first studies to explore the importance of GSA-related social justice involvement for LGBQ student safety, academic well-being, and future plans to vote. To date, only one study has readily explored LGBQ youth involvement in social justice activities: In that study, Russell and colleagues (2010) documented that the majority of LGBQ youth who were involved in queer-related social justice activities were likely to report plans for future LGBQ-related civic engagement. The current study extends beyond this initial investigation by documenting that involvement in social justice activities is associated with positive school-based outcomes, specifically school belongingness and GPA. Although engagement in social justice activities in this study was not associated with plans for future civic engagement (i.e., plans to vote), future research should continue to investigate this link for LGBQ youth, as several studies document the link between activity involvement and future civic engagement for the general population (McFarland & Thomas, 2006; Zaff et al., 2008).

This study also investigated the potential for three different facets of GSAs, with a specific focus on involvement in GSA-related social justice activities, to reduce the negative associations among school victimization based on sexual orientation and school-based outcomes and future plans to vote. We found significant interactions between involvement in GSA-related social justice activities and school victimization and, separately, GSA presence and school victimization; however, only one of these interactions can be characterized as a buffering effect. That is, the presence of a GSA seems to buffer the negative association between school victimization and future plans to vote, but this buffering effect is not present for school safety or GPA for GSA presence. Notably, the finding that students with GSAs in their schools are more likely than their counterparts to report intent to vote in the future at high levels of school victimization may suggest that GSAs provide the social context to cultivate and develop empowerment. As discussed by others (Russell et al., 2009), GSAs may be a route to promote empowerment because students commonly learn knowledge and gain experience on how to use their voice to address injustice, such as personally experienced school victimization based on sexual orientation, in this context.

We also found that for students with GSAs present in their schools, as victimization based on sexual orientation increased they reported significantly less safety at school. This finding—in combination with the other dissipating interaction effects—suggests that school administrators, teachers, students, and community members cannot accept the creation of GSAs as the final solution for creating safer school environments for LGBQ students. Indeed, these findings suggest that, even in the context of GSAs, students who experience high amounts of victimization still report lower GPAs and less school safety. This information, albeit limited, is critical as researchers, school personnel, practitioners, and policy makers continue to identify positive school-based influences and reduce health and academic disparities in the lives of LGBQ youth. Furthermore, these findings point to the critical need to reduce (or even eliminate) school victimization based on sexual orientation.

A consistent finding in this study involved the interactions between our GSA constructs and school victimization based on sexual orientation. We found that involvement in GSA-related social justice activities and the presence of a GSA were particularly beneficial for school-based outcomes at low levels of school victimization. However, neither involvement in GSA-related social justice activities nor the presence of a GSA were able to successfully buffer the negative impacts of high levels of school victimization based on sexual orientation for LGBQ youth. More important, this highlights the troublesome association between high levels of school victimization based on sexual orientation and academic well-being and suggests that research must continue to investigate the processes that place LGBQ youth at heightened risk for school victimization and the policies and programs that significantly reduce this type of victimization.

Limitations and Future Directions

One limitation of this research is that the data are cross-sectional; thus, we cannot draw any conclusions about the directionality of the associations between the facets of GSAs and school-based and civic outcomes. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of this study design limits our ability to understand the moderating influence of GSAs and social justice involvement on victimization in predicting our outcomes. Longitudinal studies are warranted that examine the associations among GSA presence, membership, social justice involvement, school victimization, and academic and civic outcomes.

A second limitation of this study is the small sample of LGBQ youth available for analyses. Our small sample limits the generalizability of our findings and potentially limited the ability to find significant effects. Given a larger sample with greater variability on study constructs, we might have found significant associations between participation in GSAs and academic outcomes, as others have found (e.g., Kosciw et al., 2010; Walls et al., 2010). Furthermore, we did not find a significant association between the presence of a GSA and student reports of safety at school. Other studies have identified this link (e.g., O’Shaughnessy et al., 2004), and one potential reason why this finding was not replicated is because of our limited statistical power. The generalizability of our findings are also limited by the recruitment method used to select participants; specifically, our sample was recruited through GSAs and LGBQ youth and community groups, which may have not captured LGBQ youth who are not involved with the LGBQ community.

A third limitation of this study was the measurement used to examine school victimization based on sexual orientation, school-based outcomes, and future civic engagement. Many of these constructs were measured with a single item; multi-item measurements are preferable, and future research needs to address this limitation. For instance, future plans for civic engagement only captured the participant’s plans for voting; however, for LGBQ youth, future civic engagement could entail plans for attending rallies about LGBQ legislation, lobbying representatives about LGBQ rights, or volunteering at an LGBQ community center. In fact, one might expect that if the current measure of plans for future civic engagement included these items, we might have found a significant relationship between current social justice engagement and future plans for engagement (e.g., Russell et al., 2010). In addition, school victimization based on sexual orientation was only measured using one item. This is limiting given the large body of literature that documents various forms of aggression that LGBQ youth may experience (e.g., physical, relational, cyber; Kosciw et al., 2010).

Future research on GSA-related social justice involvement by LGBQ youth would benefit from examining how multiple forms of diversity (e.g., ethnicity, gender, age) interact to affect involvement and developmental outcomes. Similarly, investigations on GSA-related social justice activity involvement need to examine the process by which LGBQ become involved in these activities in order to understand how to promote and sustain involvement. For instance, does LGBQ youth participation in GSAs and related social justice activities follow the same pattern for achieving civic engagement that has been identified in the general adolescent literature (e.g., participation → connection → expansion to community; Borden & Serido, 2009)? Or are there important, nuanced differences for this population that need to be identified in order to facilitate appropriate program development and school policy?

Conclusions

Although research on LGBQ youth has increased over the past 30 years, the focus has largely continued to be on risk for this population. This study attempted to provide information about positive structures and activities for LGBQ youth that are situated within the school context. The positive associations between GSA presence and school belongingness and GPA, though less novel, are still beneficial in adding to the literature that documents the protective nature of these organizations. Similarly, the findings that involvement in GSA-related social justice activities is positively associated with school belongingness and GPA are important for our continued understanding of positive contexts for LGBQ youth. Future studies are needed to provide in-depth understandings of the processes that underlie involvement in these activities and positive development for LGBQ youth.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the California Safe Schools Coalition for their support of the project, and would like to thank Noel Card and Lynne Borden for their suggestions on an earlier draft of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article, a grant from The California Endowment to the Gay-Straight Alliance Network. The research was also supported by the Frances McClelland Institute for Children, Youth, and Families, and the Fitch Nesbitt Endowment, University of Arizona. Support for the first author’s time spent on the revisions of this article was provided by a National Institute of Mental Health Training Grant (T32 MH018387) to Russell B. Toomey.

Biographies

Russell B. Toomey is a postdoctoral research fellow with the Prevention Research Center at Arizona State University. He received his PhD from the University of Arizona in Family Studies and Human Development, and his research primarily focuses on how contexts and interpersonal relationships influence health and well-being for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth.

Stephen T. Russell is distinguished professor and Fitch Nesbitt Endowed Chair in Family and Consumer Sciences in the John & Doris Norton School of Family and Consumer Sciences at the University of Arizona, and Director of the Frances McClelland Institute for Children, Youth, and Families. Stephen conducts research on adolescent pregnancy and parenting, cultural influences on parent-adolescent relationships, and the health and development of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. He is President-Elect of the Society for Research on Adolescence.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Borden L, Serido J. From program participant to engaged citizen: A developmental journey. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37:432–438. [Google Scholar]

- California Healthy Kids Survey. California Health Kids Survey: Survey content & download. 2010 Retrieved from http://chks.wested.org/administer/download.

- Diaz EM, Kosciw JG, Greytak EA. School connectedness for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: In-school victimization and institutional supports. The Prevention Researcher. 2010;17(3):15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AF, Matjasko JL. The role of school-based extracurricular activities in adolescent development: A comprehensive review and future directions. Review of Educational Research. 2005;75(2):159–210. [Google Scholar]

- Fetner T, Kush K. Gay-straight alliances in high schools: Social predictors of early adoption. Youth & Society. 2008;40:114–130. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan CA. Volunteerism, leadership, political socialization, and civic engagement. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 2. New York, NY: John Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright S, Cammarota J. New terrain in youth development: The promise of a social justice approach. Social Justice. 2002;29:82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright S, James T. From assets to agents of change: Social justice, organizing, and youth development. New Directions for Youth Development. 2002;96:27–46. doi: 10.1002/yd.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C, Szalacha L, Westheimer K. School support groups, other school factors, and the safety of sexual minority adolescents. Psychology in the Schools. 2006;43:573–589. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Cumsille PE, Elek-Fisk E. Methods for handling missing data. In: Shrinka J, Velicer W, editors. Handbook of psychology: Research methods in psychology. Vol. 2. New York, NY: John Wiley; 2003. pp. 87–114. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P, Ouellett M. From silence to safety and beyond: Historical trends in addressing lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender issues in K-12 schools. Equity & Excellence in Education. 2003;36:106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Horn SS, Nucci L. Harassment of gay and lesbian youth and school violence in America: An analysis and directions for intervention. In: Daiute C, Beykont Z, Higson-Smith C, Nucci L, editors. International perspectives on youth conflict and development. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Diaz EM. Who, what, where, when, and why: Demographic and ecological factors contributing to hostile school climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:976–988. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Diaz EM, Bartkiewicz MJ. The 2009 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. The impact of belonging to a high school gay/straight alliance. The High School Journal. 2002:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Macgillivray IK. Shaping democratic identities and building citizenship skills through student activism: Mexico’s first gay-straight alliance. Equity & Excellence in Education. 2005;38:320–330. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland DA, Thomas RJ. Bowling young: How youth voluntary associations influence adult political participation. American Sociological Review. 2006;71:401–425. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock TB, Bolch MB. Risk and protective factors for poor school adjustment in lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) high school youth: Variable and person-centered analyses. Psychology in the Schools. 2005;42:159–172. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shaughnessy M, Russell S, Heck K, Calhoun C, Laub C. Safe place to learn: Consequences of harassment based on actual or perceived sexual orientation and gender non-conformity and steps for making schools safer. San Francisco: California Safe Schools Coalition; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Espelage DL, Green HD., Jr The socialization of dominance: Peer group contextual effects on homophobic and dominance attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:1040–1050. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Russell GM, Bohan J, McCarroll M, Smith N. Trauma, recovery, and community: Perspectives on the long-term impact of anti-LGBT politics. Traumatology. 2010 doi: 10.1177/1534765610362799. Advance online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Muraco A, Subramaniam A, Laub C. Youth empowerment and high school gay-straight alliances. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:891–903. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9382-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Seif H, Truong NL. School outcomes of sexual minority youth in the United States: Evidence from a national study. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:111–127. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Toomey RB, Crockett J, Laub C. LGBT student activism and civic engagement. In: Sherrod L, Flanagan C, Torney-Purta J, editors. Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth. New York, NY: John Wiley; 2010. pp. 471–494. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:36–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD. Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1998;24:323–355. [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha LA. Safer sexual diversity climates: Lessons learned from an evaluation of Massachusetts safe schools program for gay and lesbian students. American Journal of Education. 2003;110:58–88. [Google Scholar]

- Torney-Purta J, Lehmann R, Oswald H, Schulz W. Citizenship and education in twenty-eight countries: Civic knowledge and engagement at age fourteen. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: The International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Walls NE, Kane SB, Wisneski H. Gay-straight alliances and school experiences of sexual minority youth. Youth & Society. 2010;41:307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Zaff JF, Malanchuk O, Eccles JS. Predicting positive citizenship from adolescence to young adulthood: The effects of a civic context. Applied Development Science. 2008;12:38–53. doi: 10.1080/10888690801910567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]