Abstract

Proteins derived from the thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1, which performs plant-type oxygenic photosynthesis, are suitable for biochemical, biophysical, and X-ray crystallographic studies. We developed an automated bioluminescence real-time monitoring system for the circadian clock in the thermophilic cyanobacterium T. elongatus BP-1 that uses a bacterial luciferase gene set (Xl luxAB) derived from Xenorhabdus luminescens as a bioluminescence reporter gene. A promoter region of the psbA1 gene of T. elongatus was fused to the Xl luxAB gene set and inserted into a specific targeting site in the genome of T. elongatus. The bioluminescence from the cells of the psbA1-reporting strain was measured by an automated monitoring apparatus with photomultiplier tubes. The strain exhibited the circadian rhythms of bioluminescence with a 25-h period length for at least 10 days in constant light and temperature. The rhythms were reset by light-dark cycle, and their period length was almost constant over a wide range of temperatures (30 to 60°C). Theses results indicate that T. elongatus has the circadian clock that is widely temperature compensated.

Circadian rhythms are endogenous daily fluctuations in physiological activities that have the following three characteristics: they are sustained under constant conditions with a period length of about 24 h; the phase of the rhythm is reset by environmental cues such as light-dark (LD) cycles and low-high temperature cycles; and the period of the rhythm is almost constant at physiological temperatures (5, 26). Thus far, circadian rhythms have been observed only in mesophilic organisms; we have found no reports of circadian rhythms in thermophilic organisms.

The clock gene cluster kaiABC generates circadian rhythms in the mesophilic cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 (hereafter called Synechococcus) (8). KaiA and KaiC proteins regulate the transcription of the kaiBC operon positively and negatively, respectively, and this feedback regulation is important for generating circadian oscillations (8). Kai proteins interact with each other in all possible combinations (9), and KaiA enhances the phosphorylation of KaiC (10, 28, 29). These mesophilic clock proteins are unstable, however, and their structure and function, their mutual interactions, and their reactions with their substrates in the circadian feedback processes remain unknown.

The thermophilic cyanobacteria Thermosynechococcus elongatus (30) and T. vulcanus (13), which were isolated from a Japanese hot spring, grow optimally at ca. 57°C, and their proteins are highly stable. The proteins can be easily purified, characterized for biochemical and biophysical properties, and crystallized. The photosynthetic reaction center protein complexes of photosystems I and II have been X-ray analyzed in T. elongatus (11, 31) and T. vulcanus (12). Recently, we cloned the gene cluster kaiABC from both species (7; T. Uzumaki and M. Ishiura, unpublished data), and both showed high homology with the corresponding Synechococcus gene (8). In T. elongatus, we determined the three-dimensional structure of KaiC by single-particle analysis of the purified protein by using electron microscopy (7), as well as the X-ray crystal structure of the C-terminal clock-oscillator domain of KaiA (28).

We recently established efficient procedures for gene transfer and manipulation in T. elongatus and T. vulcanus (20). We report here the development of a real-time bioluminescence monitoring system in T. elongatus, and we demonstrate circadian rhythms in a bioluminescent transgenic strain of T. elongatus in a wide range of ambient temperatures (30 to 60°C).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and manipulation of DNA.

The wild-type cells of T. elongatus BP-1 (30) were grown at 55°C under constant light from white fluorescent lamps at 50 μmol m−2 s−1 (hereafter called LL conditions) in BG-11 liquid medium (hereafter called liquid BG-11 [6]) and on BG-11 agar medium (hereafter called solid BG-11) that contained 1.5% Bacto Agar (Nippon BD, Tokyo, Japan). To permit selection and maintenance of kanamycin-resistant (Kmr) transformants, liquid BG-11 and solid BG-11 were supplemented with kanamycin at final concentrations of 100 and 75 μg/ml, respectively. Escherichia coli strain DH5α (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan) was maintained at 37°C with or without 50 μg of ampicillin/ml in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) liquid medium and on LB solid medium containing 1.5% agar in LB medium (23).

We performed DNA manipulations and sequencing by standard techniques (2, 23) and confirmed the nucleotide sequences of plasmid constructs and the subclones of PCR products by sequencing. We prepared plasmid DNAs by standard methods (23).

Construction of a reporter plasmid and a reporter strain of T. elongatus.

We amplified a 0.46-kb promoter region of the psbA1 gene (ppsbA1) of T. elongatus (17; K. Onai and M. Ishiura, unpublished results) by PCR with the genomic DNA of wild-type cells as a template and the primer set psbA1F1 (5′-TTCAGCACCCCAGAGATTTTCGGCAACGGC-3′) and psbA1R1 M (5′-GGTCATATGCGTGATAAGTCCAAATATATT-3′; the NdeI site is underlined, and the CAT sequence complementary to the ATG initiation codon of the psbA1 gene is in italics) and subcloned it into pT7Blue-T (Novagen, Madison, Wis.), giving pT7BT/ppsbA1. We amplified a 2.2-kb fragment carrying a luxAB gene set derived from Xenorhabdus luminescens strain ATCC 29999 (Xl luxAB; GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession no. M57416) by PCR with plasmid Xlux/pT7-3 (27) as a template and the primer set Xlux-F1 M (5′-CCATATGAAATTTGGAAACTTTTTGC-3′; the NdeI site is underlined, and the ATG initiation codon of the luxA gene is in italics) and Xlux-R1 M (5′-TTCTAGAAAGCTGCTGCTTTGTTGGC-3′; the XbaI site is underlined) and subcloned it into pT7Blue-T, yielding pT7BT/Xl luxAB. We excised the Xl luxAB gene segment from pT7BT/Xl luxAB as a 2.2-kb NdeI-XbaI fragment and ligated it with a larger NdeI-XbaI fragment of pT7BT/ppsbA1, producing pT7BT/ppsbA1::Xl luxAB. We excised a ppsbA1::Xl luxAB gene fusion segment from pT7BT/ppsbA1::Xl luxAB as a 2.7-kb BamHI-XbaI fragment, blunted it at the ends of the fragment by a filling-in reaction with Klenow fragment (Takara), and ligated it into the StuI site of the targeting plasmid vector pTS2Te/kmTe (20) in the opposite direction to a Kmr gene cassette (PcpcC::kmTe [20]), yielding pTS2Te/PSBA1 (Fig. 1). pTS2Te/kmTe enabled us to transfer exogenous DNA fragments to a specific targeting site (TS2Te) in the T. elongatus genome by a double crossover via homologous recombination with the PcpcC::kmTe gene as a selective marker (20).

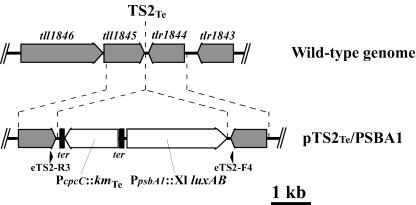

FIG. 1.

Physical map of targeting site TS2Te in the T. elongatus genome and schematic representation of reporter vector pTS2Te/PSBA1. The gray boxes with an arrowhead indicate open reading frames (ORFs) of putative genes and their reading directions. The ORF numbers assigned by the Kazusa DNA Research Institute genome project (18) are shown above each ORF. The vector contains a psbA1-reporting gene cassette (ppsbA1::Xl luxAB; shown as an open box with an arrowhead) and a Kmr gene cassette for T. elongatus (20) encoding a thermostable kanamycin nucleotidyltransferase (PcpcC::kmTe; shown as an open box with an arrowhead). The reporter construct with the selective marker gene was inserted into TS2Te (20) in the genome by double-crossing over via homologous recombination. The PCR primers used for the confirmation of the expected insertion of the reporter construct into TS2Te are shown by the arrowheads. ter, the T4 terminator sequences with opposite directions, are shown as filled boxes.

We transformed the wild-type cells of T. elongatus with pTS2Te/PSBA1 (a reporter vector) and pTS2Te/kmTe (a control vector) by natural transformation and selected the resulting Kmr transformants as colonies as described previously (20). Using the genomic DNA as a template and the primer set eTS2-F4 (5′-GCAATGCCCACAACTTCCCCCTCG-3′) and eTS2-R3 (5′-TGGTGGGCTTAGTGATTGAGCGTA-3′) (Fig. 1 [20]), we confirmed by PCR that the constructs had been inserted into the TS2Te in the T. elongatus genome as expected. We assigned the name A073 to one of the Kmr transformants obtained by transformation with the control vector pTS2Te/kmTe and used it as a control strain. We assigned the names A197 to A205 to nine genetically independent Kmr transformants obtained by transformation with the reporter vector pTS2Te/PSBA1. The growth and pigmentation of the Kmr transformants seemed normal.

Assay of bioluminescence in T. elongatus.

At temperatures below 41°C, we monitored the bioluminescence rhythms from a single colony grown on solid BG-11. At temperatures 55 and 60°C, we monitored the rhythms from liquid cultures because we could not detect bioluminescence from colonies grown at over 43°C, probably because X. luminescence luciferase was unstable at such high temperatures.

We assayed the bioluminescence from cells grown on solid BG-11 as follows. Cells were grown to colonies on solid BG-11 at 52°C for 3 days under LL conditions. Then 6-mm agar plugs carrying a single colony were punched out with a glass tube, and each plug was transferred to a well in a 96-well microplate (CulturePlate-96; Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Next, 20-μl aliquots of n-decanal (Sigma Japan, Tokyo) dissolved in salad oil (1% [vol/vol]; Nissin Foods, Tokyo, Japan) were added to the empty wells adjacent to the filled wells, and the plates were sealed with a plate seal (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences Japan) so that a constant vapor pressure would be maintained. To synchronize the circadian clock of the cells, we placed the plates in the dark for 12 h at 30, 35, or 41°C (dark conditions). After that, we returned the plates to LL conditions at their respective temperatures. The bioluminescence from each well carrying a colony was measured continuously by an automated bioluminescence-monitoring apparatus with photomultiplier tubes as photon detectors (K. Okamoto, K. Onai, T. Furusawa, and M. Ishiura, unpublished data). The apparatus is composed of three units: (i) a platform integrated with a conveying system on which 10 sample plates are set under uniform light conditions and rotated through all plate positions once in each measuring cycle; (ii) a unit that measures the bioluminescence from each well of the plate; and (iii) an analyzing computer that collects and analyzes bioluminescence data automatically. Because we separated the temperature-sensitive controlling unit from the other units, the apparatus can measure bioluminescence at up to 50°C. The measurements were made for 3 s in the dark after the cells were exposed to 180 s of darkness to permit the decay of chlorophyll fluorescence, and then the plates were returned to LL conditions. This measuring process was repeated automatically every 1 to 2 h. The 183 s of darkness did not affect circadian rhythm (data not shown).

We assayed the bioluminescence from cells grown in liquid medium as follows. We grew the cells to a stationary phase (∼2 × 109 cells/ml) in liquid BG-11 at 55 or 60°C under LL conditions with shaking at 180 rpm, incubated them in the dark for 12 h to synchronize the circadian clock under the same conditions as those in LL conditions, except for illumination, and then returned them to LL conditions. Every 3 h, we removed 500-μl from each LL culture, transferred it into a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube, and removed two 150-μl aliquots. One aliquot was used to optically determine cell density (1 optical density at 730 nm unit corresponded to a cell density of 109 cells/ml in our experimental conditions). The other was used to measure bioluminescence, as follows. The culture was mixed with 10 μl of 1% n-decanal and transferred into wells on plates, and the plates were sealed as described above and incubated for 1 h at 30°C under LL conditions to allow de novo synthesis of active luciferase. The bioluminescence was then measured for 3 s at 30°C in the dark by the monitoring apparatus described above. The 1-h incubation at 30°C did not affect circadian rhythms (data not shown).

We analyzed bioluminescence data by the visual-inspection-peak (VIP) method with linear regression (22) or the cosinor method (19) by using the RAP program (K. Okamoto, K. Onai, and M. Ishiura, unpublished data). The RAP program does all of the following in real time: (i) displays the bioluminescence time course on a monitor, (ii) records time series data, (iii) analyzes high-throughput bioluminescence data, (iv) displays the analyzed results on a monitor, (v) performs statistical analysis of the analyzed results, and (vi) prints out the time course and the analyzed results during monitoring. The VIP method recognizes rhythm peaks defined as the middle time point between the last time point where a value increases continuously for more than three time points and the first time point at which it decreases continuously for more than three time points. The period length and peak phase of rhythms are calculated from the intervals between the adjacent two peaks of rhythms by the linear regression method. The cosinor method (19) is based on Fourier analysis.

Northern blot analysis.

Cells of the psbA1-reporting strains of T. elongatus were grown on solid BG-11 in 90-mm dishes at 52°C for 3 days under LL conditions, placed in the dark for 12 h at 52°C to synchronize the circadian clock, and then returned to LL conditions at 52°C. At 3-h intervals, we harvested cells under LL conditions by washing each dish with 3 ml of liquid BG-11 and centrifuging the wash at 3,500 × g for 2 min at 4°C. The cells were resuspended in 100 μl of 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted from the frozen cells as previously described (15). RNA was separated on 1.2% agarose gels containing formaldehyde by agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to positive-charged nylon membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham Biosciences, Tokyo), and hybridized with [α-32P]dCTP-labeled psbA1-specific probe (nucleotides 1,112 to 1,592 under accession no. D14325) by standard techniques (2, 23). Signals from hybridized bands were detected and quantified with a Bio-Image Analyzer (BAS2000; Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). We normalized quantified signals against densities of ethidium bromide-stained rRNAs and analyzed the densitometric data by the cosinor method (19) by using the RAP program.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Bioluminescence rhythms observed in a psbA1 reporting strain of T. elongatus.

In a previous study, we monitored gene expression continuously as bioluminescence in the mesophilic cyanobacteria Synechococcus (14) and Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (hereafter called Synechocystis) (1). We used the luxAB gene set derived from Vibrio harveyi as a reporter gene at temperatures of ∼30°C. Because T. elongatus grows better at higher temperatures, we used as a reporter a gene set derived from X. luminescence (Xl luxAB) that encodes a thermostable luciferase. The Xl luxAB gene set encodes two different luciferase subunits—LuxA and LuxB—and Xl luciferase is more thermostable than the V. harveyi luciferase (27). We obtained nine independent transformants of a psbA1-reporting strain (A197 to A205) that carried the ppsbA1::Xl luxAB gene fusion inserted into the targeting site TS2Te in the genome and examined their bioluminescence under LL conditions at 41°C after an exposure to 12 h of darkness to synchronize the circadian clock.

Under LL conditions, the bioluminescence from each transformant oscillated rhythmically with a period length of 24.8 ± 0.3 h, and the phase of the rhythms was 23.2 ± 0.6 h after exposure to LL conditions (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The rhythms were sustained for at least 10 days. The control transformant, A073, which did not have a bioluminescence-reporting gene, did not show any significant bioluminescence.

TABLE 1.

Bioluminescence rhythms of psbA1-reporting transformants under LL conditionsa

| Transformant | Avg time (h) ± SD

|

n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period length | Phase | ||

| A197 | 24.3 ± 0.4 | 22.6 ± 0.2 | 3 |

| A198 | 24.3 ± 0.4 | 23.2 ± 0.9 | 3 |

| A199 | 24.7 ± 0.7 | 23.3 ± 0.9 | 3 |

| A200 | 24.8 ± 0.3 | 22.7 ± 1.3 | 4 |

| A201 | 24.9 ± 0.9 | 23.2 ± 1.5 | 4 |

| A202 | 24.8 ± 0.5 | 22.9 ± 1.5 | 4 |

| A203 | 24.9 ± 0.7 | 24.0 ± 1.0 | 3 |

| A204 | 25.3 ± 1.2 | 24.4 ± 1.0 | 4 |

| A205 | 24.8 ± 0.8 | 22.9 ± 1.3 | 58 |

| Total (mean) | 24.8 ± 0.3 | 23.2 ± 0.6 | 86 |

Other conditions were the same as described in the legend for Fig. 2.

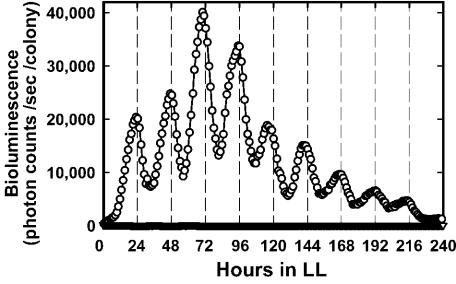

FIG. 2.

Bioluminescence rhythms of a psbA1-reporting transformant under LL conditions. Cells of a psbA1-reporting transformant (A205 cells [○]) and a negative control transformant (A075 cells [▿]) were grown as colonies on solid BG-11 at 55°C. They were exposed to 12 h of darkness at 41°C for synchronization of the circadian clock and transferred to LL conditions at 41°C for measurement of the bioluminescence from a single colony. The trace of bioluminescence from A205 cells represents one typical trace of three independent experiments. Essentially the same rhythms were observed in all of the colonies examined.

Resetting of bioluminescence rhythms by LD cycles.

We examined whether the bioluminescence rhythms observed in the psbA1-reporting strain could be reset by daily light-dark (LD) cycles. We grew A205 transformant cells as colonies on solid BG-11, exposed samples to two 12-h light, 12-h dark (i.e., LD) cycles that were 12-h out of phase, and then transferred the cells to LL conditions at 41°C in order to monitor their bioluminescence rhythms. The two samples showed bioluminescence rhythms with opposite phases and, in both cases, bioluminescent peaks occurred 23.8 h after the onset of LL conditions and again 24.8 h later (Fig. 3). These results indicate that the rhythms were reset, and their phases determined, by the LD cycle.

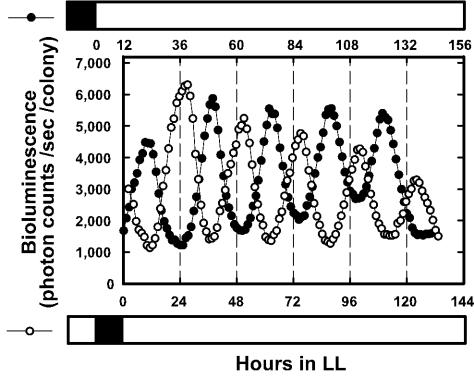

FIG. 3.

Resetting of the bioluminescence rhythms observed in a psbA1-reporting transformant by an LD cycle. Two A205 cell cultures were subjected to 12 h of darkness (▪) that were out of phase and then transferred to LL conditions (□). The light and dark schedules are shown on upper (for solid circles) and lower (for open circles) abscissas. Each trace represents one of the results obtained from three independent experiments. Other conditions were the same as described for Fig. 2.

Temperature compensation of bioluminescence rhythms.

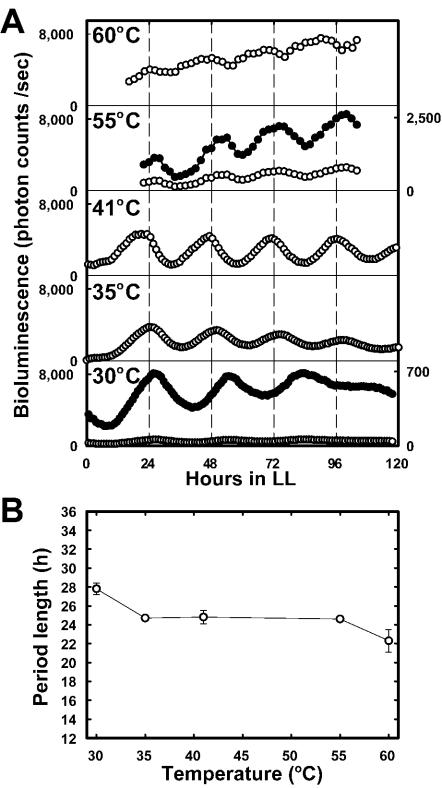

We examined the effects of temperature on period length by using the A205 psbA1-reporting strain. The period lengths ± the standard deviation of the rhythms observed under LL conditions at 30, 35, 41, 55, and 60°C were 27.4 ± 1.0 h (n = 14), 24.7 ± 0.3 h (n = 6), 24.8 ± 0.7 h (n = 32), 24.6 ± 0.3 h (n = 7), and 22.3 ± 1.2 h (n = 5), respectively (Fig. 4). The temperature coefficient (Q10) for rhythm frequency (1/period length) was estimated to be 1.08 in this temperature range; especially, the period was almost constant (Q10 = 1.00) in a temperature range between 35 and 55°C. These results indicate that the period length of the rhythms was compensated against extreme changes in ambient temperature.

FIG. 4.

Bioluminescence rhythms observed in psbA1-reporting transformants at various temperatures and their period length. (A) Rhythms at various temperatures. A205 cells were grown to colonies on solid BG-11 at 52°C and incubated at 30, 35, or 41°C or grown in liquid BG-11 at 55 or 60°C. The cells were exposed to 12 h of darkness and then transferred to LL conditions. The bioluminescence values are shown as photon counts per second per colony (at 30, 35, and 41°C) or as photon counts per second per 109 cells (at 55 and 60°C). The values observed at 30 and 55°C are also plotted in magnified scales, as shown by the right vertical axis and filled circles. Other conditions were the same as described for Fig. 2. (B) Temperature compensation of period length. The means and standard deviations of the period lengths of the rhythms are plotted at various temperatures. The values represent data from one of at least five replicate experiments.

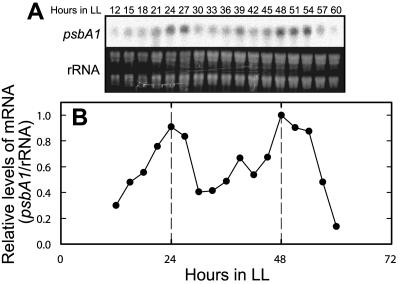

Northern blot analysis of psbA1 mRNA.

We demonstrated above that bioluminescence from the psbA1-reporting strain was controlled by the circadian clock. To determine whether the bioluminescence rhythms of the psbA1-reporting strain reflected rhythmic changes of promoter activity, we examined changes in the level of psbA1 mRNA in the cells of the A205 psbA1-reporting strain grown at 52°C under LL conditions (Fig. 5). We found that the levels oscillated rhythmically and the rhythms were similar in period length and phase to the bioluminescence rhythms. We obtained essentially the same results from the cells of a nontransgenic wild-type strain of T. elongatus (data not shown). Thus, the circadian rhythmic changes in bioluminescence level demonstrated here probably reflected the clock-controlled activities of the psbA1 promoter, although we did not examine the degradation of psbA1 mRNA.

FIG. 5.

Rhythmic changes in the amount of psbA1 mRNA in cells grown under LL conditions at 52°C. (A) Northern blot of psbA1 mRNA. (B) Densitometric data of the blots shown in panel A. The estimated period length and phase by the cosinor method (19) were 25.3 and 23.4 h, respectively.

The T. elongatus circadian clock period has wide temperature-compensation.

The bioluminescence rhythms observed in the psbA1-reporting strain apparently reflected promoter activity (Fig. 5) and satisfied the three criteria for circadian rhythms: they had a period length of about 24 h that was persistent under constant conditions (Table 1 and Fig. 2), they were reset by LD cycles (Fig. 3), and the period showed temperature compensation (Fig. 4). We therefore concluded that T. elongatus has a circadian clock and that the clock controls the activity of the psbA1 promoter.

In general, the rate of chemical, biochemical, and physiological processes varies with temperature, and their Q10 values are usually between 2 and 3. In contrast, the period length of circadian rhythms do not vary much with temperature, and the Q10 is usually 0.9 to 1.3 (5, 21, 25). The temperature compensation of the period length observed in mesophilic species is restricted to a range of <20°C (5); examples include eclosion rhythms of Drosophila sp. (4)., expansion and contraction rhythms of Cavernularia obesa colonies (16), leaf movement rhythms of Phaseolus multiflorus (3), and CAB2::LUC reporter expression rhythms of Arabidopsis thaliana (24). The period length of bioluminescence rhythms observed in the mesophilic cyanobacteria Synechococcus (14) and Synechocystis (1) has a Q10 of 1.1 within a range of only 10°C. The period we observed in T. elongatus, on the other hand, had a Q10 of 1.08 within a range of more than 30°C and a Q10 of 1.00 from 35 to 55°C, demonstrating perfect compensation within that wide range (Fig. 4).

T. elongatus is a free-living, slowly mobile, unicellular organism that shows optimum growth at ca. 55°C (29; K. Onai, M. Morishita, and M. Ishiura, unpublished). Its ability to compensate for wide temperature changes may support its survival in hot springs as well as in streams where 55°C temperatures are restricted to small areas. T. elongatus cells are viable at 30°C for at least 7 days. They are also viable at <30°C but cannot proliferate, and they can even withstand freezing (Onai et al., unpublished).

We identified a gene cluster in T. elongatus homologous to the clock gene cluster kaiABC in Synechococcus (7; Uzumaki and Ishiura, unpublished), and we found that each of the kai genes exists as a single copy in the T. elongatus genome (18; Uzumaki and Ishiura, unpublished). Presumably, the kaiABC gene cluster in T. elongatus has circadian clock functions. The large difference in the temperature range of temperature compensation between the Synechococcus and T. elongatus circadian clocks, however, suggests the existence of an additional system in T. elongatus that stabilizes the oscillations of the clock against large changes in ambient temperature.

The real-time monitoring system for bioluminescence rhythms in T. elongatus that we describe here provides great advantages for analyzing the circadian clock in the cyanobacterium. We can measure and analyze circadian rhythms within a wide ambient temperature range. The clock proteins and clock-related proteins prepared from T. elongatus are stable and provide excellent material for structure and function studies. Working with T. elongatus, we recently succeeded in determining the three-dimensional structure of KaiC (7) and the X-ray crystal structure of the C-terminal clock oscillator domain of KaiA (28). Thus, T. elongatus is one of the best model organisms for molecular dissection of the circadian clock at the atomic level, especially the mechanisms for temperature compensation of period length.

Acknowledgments

We thank Edward Meighen (McGill University) for the gift of plasmid Xlux/pT7-3 carrying the Xl luxAB gene set. We also thank Hideaki Nakashima (Okayama University) and Shigeru Itoh (Nagoya University) for critical reading of the manuscript and Miriam Bloom (SciWrite Biomedical Writing and Editing Services) for professional editing.

This study was supported by grants to M.I. from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT); The Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences (BRAIN); Research for the Future Novel Gene Function Involved in Higher-Order Regulation of Nutrition-Storage in Plants (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science); Ground-based Research for Space Utilization (Japan Space Forum); The National Project on Protein Structural and Function Analyses (MEXT); and The Promoting Cooperative Research Project (Aichi Science and Technology Foundation). The Division of Biological Science, Graduate School of Science, Nagoya University, is supported by a 21st COE grant from MEXT.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki, S., T. Kondo, and M. Ishiura. 1995. Circadian expression of the dnaK gene in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 177:5606-5611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates/Wiley Interscience, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Bünning, E. 1931. Untersuchungen über die autonomen tagesperiodischen Bewungen der Primärblätter von Phaseolus multiflorus. Jahrb. Wiss. Bot. 75:439-480. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bünning, E. 1935. Zur Kenntnis der endonomen Tagesrhythmik bei Insekten and bei Pflanzen. Ber. Deutsch. Bot. Gesellsch. 53:594-623. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bünning, E. 1973. The physiological clock: circadian rhythms and biological chronometry, 3rd ed. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 6.Castenholz, R. W. 1988. Culturing methods for cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 167:68-93. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi, F., H. Suzuki, R. Iwase, T. Uzumaki, A. Miyake, J.-R. Shen, K. Imada, Y. Furukawa, K. Yonekura, K. Namba, and M. Ishiura. 2003. ATP-induced hexameric ring structure of the cyanobacterial circadian clock protein KaiC. Genes Cells 8:287-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishiura, M., S. Kutsuna, S. Aoki, H. Iwasaki, C. R. Andersson, A. Tanabe, S. S. Golden, C. H. Johnson, and T. Kondo. 1998. Expression of a gene cluster kaiABC as a circadian feedback process in cyanobacteria. Science 281:1519-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasaki, H., Y. Taniguchi, M. Ishiura, and T. Kondo. 1999. Physical interactions among circadian clock proteins KaiA, KaiB and KaiC in cyanobacteria. EMBO J. 18:1137-1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwasaki, H., T. Nishiwaki, Y. Kitayama, M. Nakajima, and T. Kondo. 2002. KaiA-stimulated KaiC phosphorylation in circadian timing loops in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:15788-15793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan, P., P. Fromme, H. T. Witt, O. Klukas, W. Saenger, and N. Krauss. 2001. Three-dimensional structure of cyanobacterial photosystem I at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature 411:909-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamiya, N., and J.-R. Shen. 2003. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus vulcanus at 3.7-Å resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:98-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koike, H., and Y. Inoue. 1983. Preparation of oxygen-evolving photosystem II particles from a thermophilic blue-green alga, p. 257-263. In Y. Inoue, A. R. Crofts, N. Govindjee, N. Murata, G. Renger, and K. Satoh (ed.), The oxygen evolving system of photosynthesis. Academic Press, Inc., Tokyo, Japan.

- 14.Kondo, T., C. A. Strayer, R. D. Kulkarni, W. Taylor, M. Ishiura, S. S. Golden, and C. H. Johnson. 1993. Circadian rhythms in prokaryotes: luciferase as a reporter of circadian gene expression in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:5672-5676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohamed, A., and C. Jansson. 1989. Influence of light on accumulation of photosynthesis-specific transcripts in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803. Plant Mol. Biol. 13:693-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori, S. 1960. Influence of environmental and physiological factors on the daily rhythmic activity of a sea pen. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 25:333-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motoki, A., T. Shimazu, M. Hirano, and S. Katoh. 1995. The two psbA genes from the thermophilic cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus. Plant Physiol. 108:1305-1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura, Y., T. Kaneko, S. Sato, M. Ikeuchi, H. Katoh, S. Sasamoto, A. Watanabe, M. Iriguchi, K. Kawashima, T. Kimura, Y. Kishida, C. Kiyokawa, M. Kohara, M. Matsumoto, A. Matsuno, N. Nakazaki, S. Shimpo, M. Sugimoto, C. Takeuchi, M. Yamada, and S. Tabata. 2002. Complete genome structure of the thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1. DNA Res. 9:123-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson, W., Y. L. Tong, J. K. Lee, and F. Halberg. 1979. Methods for cosinor-rhythmometry. Chronobiologia 6:305-323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onai, K., M. Morishita, T. Kaneko, S. Tabata, and M. Ishiura. 2004. Natural transformation of the thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1: a simple and efficient method for gene transfer. Mol. Genet. Genomics 271:50-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pittendrigh, C. S. 1954. On temperature independence in the clock system controlling emergence time in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 40:1018-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pittendrigh, C. S., and S. Daan. 1976. A functional analysis of circadian pacemakers in nocturnal rodents. I. The stability and liability of spontaneous frequency. J. Comp. Physiol. 106:223-252. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, N.Y.

- 24.Somers, D. E., A. A. R. Webb, M. Pearson, and S. A. Kay. 1998. The short-period mutant, toc1-1, alters circadian clock regulation of multiple outputs throughout development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 125:485-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sweeney, B. M., and J. W. Hastings. 1960. Effects of temperature upon diurnal rhythms. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 25:87-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sweeney, B. M. 1987. Rhythmic phenomena in plants, 2nd ed. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 27.Szittner, R., and E. Meighen. 1990. Nucleotide sequence, expression, and properties of luciferase coded by lux genes from a terrestrial bacterium. J. Biol. Chem. 265:16581-16587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uzumaki, T., M. Fujita, T. Nakatsu, F. Hayashi, H. Shibata, N. Itoh, H. Kato, and M. Ishiura. Crystal structure of the C-terminal clock-oscillator domain of the cyanobacterial KaiA protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Williams, S. B., I. Vakonakis, S. S. Golden, and A. C. LiWang. 2002. Structure and function from the circadian clock protein KaiA of Synechococcus elongatus: a potential clock input mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:15357-15362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamaoka, T., K. Satoh, and S. Katoh. 1978. Photosynthetic activities of a thermophilic blue-green alga. Plant Cell Physiol. 19:943-954. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zouni, A., H. T. Witt, J. Kern, P. Fromme, N. Krauss, W. Saenger, and P. Orth. 2001. Crystal structure of photosystem II from Synechococcus elongatus at 3.8 Å resolution. Nature 409:739-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]