Abstract

Homozygosity has long been associated with rare, often devastating, Mendelian disorders1 and Darwin was one of the first to recognise that inbreeding reduces evolutionary fitness2. However, the effect of the more distant parental relatedness common in modern human populations is less well understood. Genomic data now allow us to investigate the effects of homozygosity on traits of public health importance by observing contiguous homozygous segments (runs of homozygosity, ROH), which are inferred to be homozygous along their complete length. Given the low levels of genome-wide homozygosity prevalent in most human populations, information is required on very large numbers of people to provide sufficient power3,4. Here we use ROH to study 16 health-related quantitative traits in 354,224 individuals from 102 cohorts and find statistically significant associations between summed runs of homozygosity (SROH) and four complex traits: height, forced expiratory lung volume in 1 second (FEV1), general cognitive ability (g) and educational attainment (nominal p<1 × 10−300, 2.1 × 10−6, 2.5 × 10−10, 1.8 × 10−10). In each case increased homozygosity was associated with decreased trait value, equivalent to the offspring of first cousins being 1.2 cm shorter and having 10 months less education. Similar effect sizes were found across four continental groups and populations with different degrees of genome-wide homozygosity, providing convincing evidence for the first time that homozygosity, rather than confounding, directly contributes to phenotypic variance. Contrary to earlier reports in substantially smaller samples5,6, no evidence was seen of an influence of genome-wide homozygosity on blood pressure and low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, or ten other cardio-metabolic traits. Since directional dominance is predicted for traits under directional evolutionary selection7, this study provides evidence that increased stature and cognitive function have been positively selected in human evolution, whereas many important risk factors for late-onset complex diseases may not have been.

Inbreeding influences complex traits through increases in homozygosity and corresponding reductions in heterozygosity, most likely resulting from the action of deleterious (partially) recessive mutations8. For polygenic traits, a systematic association with genome-wide homozygosity is not expected when dominant alleles at some loci increase the trait value while others decrease it. Rather, dominance must be biased in one direction on average over all causal loci, for instance to decrease the trait. Such directional dominance is expected to arise in evolutionary fitness-related traits due to directional selection8. Studies of genome-wide homozygosity thus have the potential to reveal the non-additive allelic architecture of a trait and its evolutionary history. Historically inbreeding has been measured using pedigrees9. However, such techniques cannot account for the stochastic nature of inheritance, nor are they practical for the capture of the distant parental relatedness present in most modern day populations. High density genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array data can now be used to assess genome-wide homozygosity directly, using genomic runs of homozygosity (ROH). Such runs are inferred to be homozygous-by-descent and are common in human populations10-11. SROH is the sum of the length of these ROH, in megabases of DNA. FROH is the ratio of SROH to the total length of the genome. Like pedigree-based F (with which it is highly correlated3), FROH estimates the probability of being homozygous at any site in the genome. FROH has been shown to vary widely within and between populations12 and is a powerful method of detecting genome-wide homozygosity effects13.

We found marked differences by geography and demographic history in both the population mean SROH and the relationship between SROH and NROH (the numbers of separate runs of homozygosity). (Fig. 1). As observed previously3,12,14, isolated populations have a higher burden of ROH whereas African heritage populations have the least homozygosity.

Figure 1. Runs of Homozygosity by Cohort.

The sum of runs of homozygosity (SROH) and the number of runs of homozygosity (NROH) are shown by sub-cohort. . Populations differ by an order of magnitude in their mean burden of ROH. There are clear differences by continent and population type both in the mean SROH, and the relationship between SROH and NROH.. SC.Asian is South & Central Asian, E.Asian is East Asian, Eur.Isolate is European isolates. The ten most homozygous cohorts are labelled: AMISH are the Old Order Amish from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania; HUTT, S-Leut Hutterites from South Dakota; NSPHS, North Swedish Population Health Study, 06 and 09 suffixes are different sampling years from different counties in Northern Sweden; OGP, Ogliastra Genetic Park, Sardinia, Italy; Talana is a particular village in the region; FVG, Friuli-Venezia-Giulia Genetic Park, Italy, omni and 370 suffices refer to subsets genotyped with the Illumina OmniX and 370CNV arrays; HELIC, Hellenic Isolates, Greece, from Pomak villages in Thrace, and CLHNS, Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Study in the Philippines.

We studied βFROH, defined as the effect of FROH on 16 complex traits of biomedical importance (Fig. 2). For height, FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in one second, a measure of lung function), educational attainment (EA) and g (a measure of general cognitive ability derived from scores on several diverse cognitive tests), we found the effect sizes were greater than two intra-sex standard deviations (SD), with p-values all less than 10−5. Thus the associations could not plausibly be explained by chance alone (Table 1; see Extended data Figs. 1-4 for Forest plots of individual traits; Supplementary Table 1 for SD). To ensure that the results were not driven by a few outliers, we repeated the analysis excluding extreme sub-cohort trait results. In all cases the effect sizes and their significance remained similar or increased (see Supplementary Table 2 for comparisons with and without outliers). After exclusion of outliers, these effect sizes translate into a reduction of 1.2 cm in height and 137 ml in FEV1 for the offspring of first cousins, and into a decrease of 0.3 SD in g and 10 months less educational attainment.

Figure 2. Effects of genome-wide homozygosity, βFROH, on 16 traits.

Four phenotypes show a significant effect of burden of ROH: height (145 sub-cohorts), FEV1 (34), educational attainment (47) and general cognitive ability, g (23). HDL and total cholesterol are not significantly different from zero after correcting for 16 tests and no effect is observed for the other traits. To account for the different numbers of males and females in cohorts and marked effect of sex on some traits, trait units are intra-sex standard deviations. βFROH is the estimated effect of FROH on the trait, where FROH is the ratio of the SROH to the total length of the genome. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are also plotted. + indicates phenotype was rank transformed, * indicates phenotype was log transformed. BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; FP fasting plasma; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c (glycated haemoglobin); FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein.

Table 1. Effects of genome-wide burden of runs of homozygosity on four traits.

P-association is P value for association, P-heterogeneity is P value for heterogeneity in a meta-analysis between trait and unpruned FROH, βFROH-SD is the effect size estimate of FROH expressed in units of intra-sex phenotypic standard deviations and SE is the standard error. βFROH-units is the effect size estimate for FROH = 1 expressed in the measurement units and SE the standard error. The P values for those traits showing evidence for association are calculated including 5 outlying cohort-specific effect size estimates (an outlier was defined as T-test statistic over 3 for the null hypothesis that the cohort effect size estimate equals the meta-analysis effect size estimate), which is conservative as the majority of these are in the opposite direction. Beta estimates however exclude these outliers, for which there is evidence of discrepancy, and should thus be more accurate. + indicates phenotype was rank transformed; FEV1 is forced expiratory lung volume in one second; g is the general cognitive factor (first unrotated principal component of test scores across diverse domains of cognition).

| Phenotype | Outliers | Height | FEV1+ | Educational Attainment | Cognitive g+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | 354,224 | 64,446 | 84,725 | 53,300 | |

| P-association | Included | <1 × 10−300 | 2.1 × 10−6 | 1.8 × 10−10 | 2.5 × 10−10 |

| P-heterogeneity | Included | 0.014 | 0.10 | 1.2 × 10−5 | 0.071 |

| βFROH-SD | Excluded | −2.91 | −3.48 | −4.69 | −4.64 |

| SE βFROH-SD | Excluded | 0.21 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.73 |

| βFROH-units | Excluded | −0.188 | −2.2 | −12.9 | −4.64 |

| SE βFROH-units | Excluded | 0.014 | 0.46 | 1.83 | 0.73 |

| Units | m | litres | years | SD | |

| First cousin offspring effect | Excluded | −1.2 | −137 | −9.7 | −0.29 |

| Units | cm | ml | months | SD |

We performed a number of analyses to exclude confounding. Whilst SROH is wholly a genetic effect, its inheritance is entirely non-additive. Therefore, unlike in genome-wide association, an association with population genetic structure or co-segregation of additive genome-wide polygenic effects and SROH (as opposed to SNPs in a GWAS) are not expected as a matter of course, except in the case of siblings. However, confounding could still theoretically arise as discussed below. We therefore assessed this by conducting stratified and covariate analyses. We found effects of similar magnitude and in the same direction for all four traits across isolated and non-isolated European, Finnish, African, Hispanic, East Asian and South and Central Asian populations (Extended Data Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table 3). We further tested whether the effect sizes were similar when cohorts were split into more and less homozygous groups. The effect sizes were very similar even though the degree of homozygosity (and variation in homozygosity) varied 3-10-fold between the two strata (depending on which cohorts contributed to the trait; Extended Data Fig. 5b). This suggests a broadly linear relationship with SROH. In general confidence intervals overlap for stratified estimates, suggesting differences arose due to sampling variance. Larger confidence intervals for some estimates reflect the lower power of some strata, in turn reflecting the sample size and degree of homozygosity of those strata (e.g. the wider confidence intervals for estimates of Educational Attainment βFROH for Finnish and African strata). Finally, we fitted educational attainment as a proxy for potential confounding by socio-economic status; this covariate was available in sufficient (47) cohorts to maintain power. The estimated effect sizes for height, FEV1 and g all reduced (17%, 18% and 35%, Fig. Extended Data Fig. 5c), but this might have been expected given the known covariance between these three traits and EA, and the association we found between educational attainment and FROH. We found very small differences (3-11% reductions) in estimated βFROH (Extended Data Fig. 6, supplementary table 4), when comparing the fitting of polygenic mixed models as opposed to fixed-effect-only models, again suggesting that confounding (in this case due to polygenic effects due to recent common ancestry) was not substantially affecting the results.

Despite the observed 17-35% reductions in estimated effect sizes for FROH on height, FEV1 and g, when fitting educational attainment as a covariate, the persistence of an effect suggests that most of the signals we observe are genetic. The consistency of effects with and without fitting relatedness and in particular in populations with very different degrees of homozygosity, all appear inconsistent with confounding due to environmental or additive genetic effects. As does the broad similarity in effect sizes across continents, although the relatively smaller numbers of cohorts of non-European descent meant we had limited power to detect inter-continental differences in effect sizes.

It is also interesting to consider the potential influence of assortative mating, which is commonly observed for human stature, cognition and education. The phenotypic extremes could be more genetically similar to each other and hence the offspring more homozygous, even if the highly polygenic trait architectures reduce this effect. However, at least in its simplest balanced form, the increase in genetic similarity would be equal at both ends of the phenotypic distribution, leading to no linear association between such genetic similarity and the trait; both tall and short people would be more homozygous. Furthermore, humans also mate assortatively on body mass index (BMI), for which we see no effect. A more complex possibility, a form of reverse-causality, could arise when subjects from one trait extreme (e.g. more educated people) are on average more geographically mobile, and thus have less homozygous offspring, with those offspring in turn inheriting the trait extreme concerned15. We do not think that this mechanism can account for our results, since it does not readily explain the constancy of our results under different models, especially the similarity in βFROH for either more or less homozygous populations. Moreover, we observe similar effects in multiple single village cohorts, and the Amish and Hutterites, where there is no geographic structure and/or no sampling of immigrants, hence such confounding by differential migration cannot occur.

Our estimate for the effect of homozygosity in height is consistent with previous work: genomic4 and pedigree16 studies have shown genome-wide homozygosity effects on stature with similar effect sizes (0.01 increase in F decreases height by 0.037 SD16 versus 0.029 SD in the present study). We speculate that homozygosity is acting on a shared endophenotype of torso size which we detect in the height and FEV1 traits. The fact that the FEV1/FVC (forced vital capacity) ratio is not associated with ROH points to the effect being on lung/chest size rather than airway calibre. The cognition effects cannot be wholly generated by height as an intermediate cause, given the greater proportion of variance explained for cognition, although we note that the correlation between height and cognition is 0.16 (SE 0.01), and the genetic correlation (the correlation in additive genetic values) is 0.28 (SE 0.09; ref 17). Height is the canonical human complex trait, highly heritable and polygenic, with 697 genome-wide significant variants in 423 loci explaining 20% of the heritability and all common variants predicted to explain 60% of the heritability18. Most of the genetic architecture appears to be additive in nature, however ROH analysis reveals a distinct directional dominance component.

Our genomic confirmation of directional dominance for g and discovery of genome-wide homozygosity effects on educational attainment in a wide range of human populations adds to our knowledge of the genetic underpinnings of cognitive differences, which are currently thought to be largely due to additive genetic effects19. Our findings go beyond earlier pedigree-based analyses of recent consanguinity to demonstrate that the observed effect of genome-wide homozygosity is not a result of confounding and influences demographically diverse populations across the globe. The estimated effect size is consistent with pedigree data (0.01 increase in F decreases g by 0.046 SD in our analysis and 0.029-0.048 SD in pedigree-based studies)20. It is germane to note that one extreme of cognitive function, early onset cognitive impairment, is strongly influenced by deleterious recessive loci21, so we can speculate that an accumulation of recessive variants of weaker effect may influence normal variation in cognitive function. Although increasing migration and panmixia have generated a secular trend in decreasing homozygosity22, the Flynn effect, wherein succeeding generations perform better on cognitive tests than their predecessors23, cannot be explained by our findings, because the intergenerational change in cognitive scores is much larger than the differences in homozygosity would predict. Likewise, the genome-wide homozygosity effect on height cannot explain a significant proportion of the observed inter-generational increases24.

Inbreeding depression, which arises from the effect of genome-wide homozygosity, is ubiquitous in plants and is seen for numerous fitness-related traits in animals25, but we observed no effect for the 12 other mainly cardio-metabolic traits in which variation is strongly age-related. This suggests that previous reports in ecological studies or substantively smaller studies using pedigrees or relatively small numbers of genetic markers may have been false positives5,6. The lack of directional dominance on these traits does not, however, rule out a recessive component, as recessive variants acting in different directions will cancel out. Dominance variance is predicted to be greater for late-onset fitness traits26, so the lack of genome-wide homozygosity effects in the cardio-metabolic traits may be due to lack of directional dominance. ROH analyses within specific genomic regions are warranted to map recessive effects even when there is no genome-wide directional dominance. Such recessive effects have been observed for a subset of cardiovascular risk factors27 and expression traits28.

We have demonstrated the existence of directional dominance on four complex traits (stature, lung function, cognitive ability and educational attainment) whilst showing any effect on the other 12 health-related traits is at least almost an order of magnitude smaller or non-existent. This directional dominance implies that size and cognition (like schizophrenia protective alleles29) have been positively selected in human history – or at least that some variants increasing these traits contribute to fitness. However, the lack of any evidence for an association between many late onset cardiovascular disease risk factors and ROH is perhaps surprising and suggests testing directly for an association between ROH and disease outcome. The magnitude of genome-wide homozygosity effects is relatively small in all cases, thus Darwin’s supposition30 of “any evil [of inbreeding] being very small” is substantiated.

METHODS

Outline

Our aim was to look for an association between a genetic effect (SROH) and 16 complex traits. Our approach followed best practice genome-wide association meta-analysis (GWAMA) protocols, where applicable, except we had only one genetic effect to test.

Cohorts were invited to join based on known previous participation in GWAMA and willingness to participate. 159 sub-cohorts were created from 102 population-based or case-control genetic studies, by separating different genotyping arrays, cases and controls or ethnic sub-groups to ensure each sub-cohort was homogeneous. Within each of the 159 sub-cohorts we measured the association between SROH and trait using the following model. Where a sub-cohort had been ascertained on the basis of a disease status associated with a particular trait, that sub-cohort was excluded from the corresponding trait analysis.

Phenotype was regressed on genetic effect and known relevant covariates within each cohort, under the model specified in Equation 1. The estimated genetic effect of SROH was then meta-analysed using inverse variance meta-analysis.

| Equation (1) |

Where Y is the vector of trait values, μ the intercept, b1 the effect of SROH and b2-6 the effect of covariates. PC1 – PC3, the post quality control within-cohort principal components of the cohort’s relationship matrix and e the residual. Relationship matrices were determined genomically by each cohort using genome wide array data. In addition, any other cohort-specific covariates known to be associated with the trait, including further principal components, and any trait-specific covariates and stratifications, such as medication and smoking status, were fitted as specified below. SROH was the sum of ROH called, with a length of at least 1.5 Mb using PLINK31.

As is routine in GWAMA, for family-based studies only, we also fitted an additional term to account for additive genetic values and relatedness, using grammar+ type residuals and full hierarchical mixed modeling using GenABEL32 and hglm33, as specified in equation 2.

| Equation (2) |

Where a is the additive genetic value of each individual. Var(a) is assumed to be proportionate to the Genomic Relationship matrix (GRM) (a pedigree relationship matrix was used in the Framingham Heart Study) . Z is the identity matrix.

We then meta-analysed the regression coefficients (b1) of traits on SROH for the 159 subcohorts.

Cohort Recruitment

Data from 102 independent genetic epidemiology studies of adults were included. All subjects gave written informed consent and studies were approved by the relevant research ethics committees. Homogeneous sub-cohorts were created for analysis on the basis of ethnicity, genotyping array or other factors. Where a cohort had multiple ethnicities, sub-cohorts for each separate ethnicity were created and analysed separately. In all cases European-, African-, South or Central Asian-, East Asian- and Hispanic-heritage individuals were separated. In some cases sub-categories such as Ashkenazi Jews were also distinguished. Ethnic outliers were excluded, as were the second of any monozygotic twins and pregnant subjects. Continental ancestry of cohorts participating in each trait study is presented in Extended data Table 1. Cohort genotyping and summary information are shown in Supplementary Table 6, with age, sex, trait and homozygosity summary statistics given in Supplementary Tables 9,10,, and 11.For case-control and trait extreme studies, patients or extreme-only sub-cohorts were analysed separately to controls. Where case status was associated with the trait under analysis the sub-cohort was excluded from that study (see below).

Subjects within a sub-cohort were genotyped using the same SNP array, or where two very similar arrays were used (e.g. Illumina OmniExpress and IlluminaOmni1), the intersection of SNPs on both arrays – provided the intersection exceeded 250,000 SNPs. Where a study used two different genotyping arrays, separate subcohorts were created for each array, and analysis was done separately. Paediatric cohorts were not included.

Genotyping

All subjects were genotyped using high density genome-wide (>250,000 SNP) arrays, from Illumina, Affymetrix or Perlegen. Custom arrays were not included. Each study’s usual array-specific genotype quality control standards for genome-wide association were used and are shown in Supplementary Table 6. Only autosomal data were analysed.

Phenotyping

We studied 16 quantitative traits which are widely available and represent different domains related to health, morbidity and mortality: height, body mass index (BMI), waist : hip ratio (WHR), diastolic and systolic blood pressure (DBP, SBP), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), fasting insulin (FI), Haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), total-, HDL- and LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FVC), general cognitive ability (g) and years of educational attainment (EA). Phenotypic QC was performed locally to assess the accuracy and distribution of phenotypes and covariates. Further covariates were included when the relevant GWAS consortium also included them. The trait categories were anthropometry, blood pressure, glycaemic traits, classical lipids, lung function, cognitive function and educational attainment, following models in the GIANT34, ICBP35, MAGIC36, CHARGE37, Spirometa38 and SSGAC39 consortia. The model for FEV1 did not include height as a covariate. Effect sizes for FEV1 therefore include size effects that also underpin height. Studies assembled files containing study traits and the following covariates: sex, age, first three principal components of ancestry, lipid-lowering medication, ever-smoker status, anti-hypertensive medication, diabetes status and year of birth (YOB). Educational attainment was defined in accordance with the ISCED 1997 classification (UNESCO), leading to seven categories of educational attainment that are internationally comparable39. LDL values estimated using Friedewald’s equation were accepted. Cohorts without fasting samples did not participate in the LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting insulin or fasting plasma glucose analyses. Cohorts with semi-fasting samples fitted a categorical or quantitative fasting time variable as a covariate. Subjects with less than 4 hours fasting were not included.

Where subjects were ascertained, for example, on the basis of hypertension, that sub-cohort was excluded from analysis of traits associated with the disorder, for example blood pressure. The traits excluded from meta-analysis are as follows: ascertainment on type-2-diabetes, thus fasting insulin, HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose excluded; ascertainment on hypertension, thus blood pressures excluded; ascertainment on venous thrombosis or coronary artery disease, thus blood lipids excluded; ascertainment on obesity or the metabolic syndrome, thus blood lipids, body mass index, waist-hip ratio, fasting insulin and fasting plasma glucose excluded.

Somewhat unusually for a large consortium meta-analysis, the majority of the analysis after initial genotype and phenotype QC was performed by a pipeline of standardised R and shell scripts, to ensure uniformity and reduce the risk of errors and ambiguities (available at https://www.wiki.ed.ac.uk/display/ROHgen/Analysis+Plan+production+release+3.0). The pipeline was used for all stages from this point onwards.

Calling Runs of Homozygosity

SNPs with more than 3% missingness across individuals or with a minor allele frequency less than 5% were removed. ROH were defined as runs of at least 50 consecutive homozygous SNPs spanning at least 1500 kb, with less than a 1000 kb gap between adjacent ROH and a density of SNP coverage within the ROH of no more than 50 kb/SNP, with one heterozygote and 5 no calls allowed per window, and were called using PLINK31, with the following settings --homozyg-window-snp 50 --homozyg-snp 50 --homozyg-kb 1500 --homozyg-gap 1000 --homozyg-density 50 --homozyg-window-missing 5 --homozyg-window-het 1. The same criteria were used by McQuillan et al.3, except SNP density has been relaxed to avoid regions of sparser coverage (still including 50 SNPs) being missed. The sum of runs of homozygosity was then calculated (SROH) . F was calculated as SROH/(3×109 ROH ) reflecting the length of the autosomal genome. Copy number variants (CNV) are known to influence cognition40; however, prior calling of CNV and ROH in one of our cohorts reduced the SROH by only 0.3%3, making it implausible that deletions called as ROH influence our findings.

ROH called from different genotyping arrays

We show that SROH called with these parameters is relatively insensitive to the density and type of array used (Extended data Fig. 7). We used 2.5 million SNPs available for 851 HapMap and 1000 Genomes Project41 samples from multiple continents to investigate the effect of array when using our ROH-calling parameters in plink. The dataset included samples of African, European, admixed American, South and East Asian heritage. By subsampling SNPs from the 2.5 million we created array data for the commonly used Illumina CNV370 and OmniExpress beadchips and the Affymetrix6 array for each individual (see Supplementary Table 7 for details of the SNP numbers). The correlation in SROH using different arrays on the same individuals was 0.93-0.94 for all pairwise chip comparisons.

Trait association with SROH

The association between trait and SROH was calculated using a linear model in accordance with equation 1. Additional covariates were fitted for some analyses (shown below) or for some cohorts where analysts were aware of study specific effects (e.g. study centre). For BMI, WHR, FEV1, FEV1/FVC and g, trait residuals were calculated for the model excluding SROH, these residuals were then rank-normalised and the effect of SROH on these rank-normalised residuals estimated. Triglycerides and fasting insulin were natural log transformed. Additional covariates were as follows: age2 was included as a covariate for all traits apart from height and g. BMI was included as a covariate for WHR, SBP, DBP, FPG, FI and HbA1c. YOB was included as a covariate for educational attainment and ever-smoking for FEV1 and FEV1/FVC. Where a subject was known to be taking lipid-lowering medication, total cholesterol was adjusted by dividing by 0.8. Similarly, where a subject was known to be taking anti-hypertensive medication, SBP and DBP measurements were increased by 15 and 10 mm Hg, respectively.

Where the cohort was known to have significant kinship, genetic relatedness was also fitted, using the mixed model, in accordance with equation 2. The polygenic model was fitted in GenABEL using the fixed covariates and the genomic relationship matrix32. GRAMMAR+ (GR+) (ref. 42) residuals were then fitted to SROH as well as the full mixed model being fitted simultaneously, using GenABEL’s hierarchical generalised linear model (HGLM) function33. Populations with kinship thus potentially had three estimates of βFROH: using fixed effects only, and using the mixed model approaches, (GR+ and HGLM) for SROH.

To investigate potential confounding, where available, EA was added as an ordinal covariate and all models rerun, giving revised estimates of βFROH. This is potentially an over adjustment for g due to the phenotypic and genetic correlations with EA43. However it must be recognised that EA does not capture all potential environmental confounding.

Cohort phenotypic means and standard deviations were checked visually for inter-cohort consistency, with apparent outliers then being corrected (e.g. due to units or incorrectly specified missing values), explained (e.g. due to different population characteristics) or excluded. Individual sub-cohort trait means and standard deviations are tabulated in Supplementary Table 9 and age and gender information is in Supplementary Table 10.

Meta-analysis

Again as is routine in GWAMA, analysis was performed within homogeneous sub-populations and only meta-analysis of the estimated (within population) effect sizes was used to combine results between populations, avoiding any confounding effects of inter-population differences in trait or genetic effect distributions. Inverse-variance meta-analysis of all sub-cohorts’ effect estimates was performed using Rmeta, on a fixed effect basis (Supplementary Table 5 compares random effects meta-analysis). In the principal analyses, for cohorts with relatedness, HGLM estimates of βFROH were preferred, however where HGLM had failed to converge, results using GRAMMAR+ were included. These results were combined with those for unrelated cohorts on a fixed model only basis. Result outliers were defined as individual cohort by trait results, which failed the hypothesis, cohort (βFROH) = pre-QC meta-analysis (βFROH), with a t-test statistic >3. Analyses were performed with and without outliers for βFROH in phenotypic units and in intra-sex phenotypic standard deviations (Supplementary Table 8). The principal results we present are for FROH with outliers included for the hypothesis tests (which turns out to be more conservative), but with outliers excluded when estimating βFROH (ref. 44). Meta-analysis was performed using inverse variance meta-analysis in the R package Rmeta, with βFROH taken as a fixed effect and alternatively as a random effect. The principal results are on a fixed effects basis, with Supplementary Table 5 showing comparison with the random effects analysis.

Meta-analyses were rerun for various subsets, according to geographic and demographic features of the cohorts. Cohorts were divided into more homozygous and less homozygous strata with the boundary being set so each within-stratum meta-analysis had equal statistical power.

Extended Data

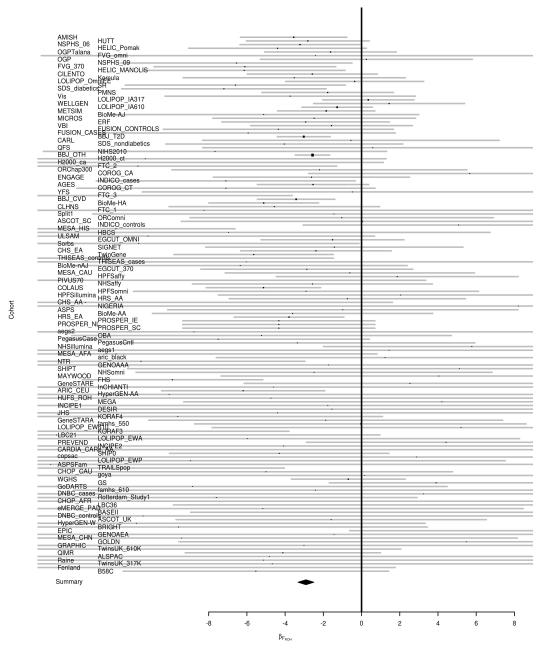

Extended Data Figure 1. Forest plot for cognitive g.

Individual sub-cohort estimates of effect size and the standard error are plotted. Sub-cohorts are ordered from top to bottom according to their weight in the meta-analysis, so larger or more homozygous cohorts appear towards the top. The scale of beta FROH is in intra-sex standard deviations. The meta-analytical estimate is displayed at the bottom. Sub-cohort names follow the conventions detailed in Supplementary Table 6 and the Supplementary Table 11 legend. Sample sizes, effect sizes and P values for association are given in Table 1. This trait was rank transformed.

Extended Data Figure 2. Forest plot for educational attainment.

Individual sub-cohort estimates of effect size and the standard error are plotted. Subcohorts are ordered from top to bottom according to their weight in the meta-analysis, so larger or more homozygous cohorts appear towards the top. The scale of beta FROH is in intra-sex standard deviations. The meta-analytical estimate is displayed at the bottom. Sub-cohort names follow the conventions detailed in Supplementary Table 6 and the Supplementary Table 11 legend. Sample sizes, effect sizes and P values for association are given in Table 1.

Extended Data Figure 3. Forest plot for height.

Individual sub-cohort estimates of effect size and the standard error are plotted. Subcohorts are ordered from top to bottom according to their weight in the meta-analysis, so larger or more homozygous cohorts appear towards the top. The scale of beta FROH is in intra-sex standard deviations. The meta-analytical estimate is displayed at the bottom. Sub-cohort names follow the conventions detailed in Supplementary Table 6 and the Supplementary Table 11 legend. Sample sizes, effect sizes and P values for association are given in Table 1.

Extended Data Figure 4. Forest plot for forced expiratory lung volume in one second.

Individual sub-cohort estimates of effect size and the standard error are plotted. Subcohorts are ordered from top to bottom according to their weight in the meta-analysis, so larger or more homozygous cohorts appear towards the top. The scale of beta FROH is in intra-sex standard deviations. The meta-analytical estimate is displayed at the bottom. Sub-cohort names follow the conventions detailed in Supplementary Table 6 and the Supplementary Table 11 legend. Sample sizes, effect sizes and P values for association are given in Table 1. This trait was rank transformed.

Extended Data Figure 5. Signals of directional dominance are robust to stratification by geography or demographic history or inclusion of educational attainment as covariate.

(a) Cohorts are divided by continental biogeographic ancestry (African (15 sub-cohorts), East Asian (5), South & Central Asian (10), Hispanic (3)), with Europeans being divided into Finns (13), other European isolates (self-declared, 23), and (non-isolated) Europeans (90). Meta-analysis was carried out for all subsets with 2000 or more samples available. Sample numbers are as follows: cognitive g, Eur isolate 6638, European 44,153; educational attainment, African 4811, Eur isolate 8032, European 55,549, Finland 9068; height, African 21,500, E Asian 30,011, Eur isolate 23,116, European 228,813, Finland 30,427, Hispanic 5469, SC Asian 13,523; FEV1, African 6604, Eur isolate 4837, European 49,223, Finland 2340. βFROH is consistent across geography and in both isolates and more cosmopolitan populations. (b) Cohorts were divided into High and Low ROH strata of equal power and meta-analysis repeated – the effects are consistent across strata for all four traits. The mean SROH for the high and low strata are 13.4 and 4.3 Mb for cognitive g; 28.1 and 5.1 Mb for education attained; 31.9 and 10.8 Mb for height; and 41.4 and 4.5 Mb for FEV1. (c) To assess the potential for socio-economic confounding, where available, educational attainment was included in the regression model (edu) and compared to a model without educational attainment (none) in the same subset of cohorts. The signals reduce slightly when the education covariate is included; the analysis is not possible for educational attainment as a trait. For cognitive g, numbers are 36847 and 36023 for edu and none; for height 131,614 and 120,945; and for FEV1, 15717 and 15425. The numbers differ because of missing individual educational data within cohorts. + indicates phenotype was rank transformed. FEV1, forced expiratory lung volume in one second; g is the general cognitive component (first unrotated principal component of test scores across diverse tests of cognition); SC Asian is South & Central Asian, E Asian is East Asian, trait units are intra-sex standard deviations and the genomic measure is unpruned SROH.

Extended Data Figure 6. Signals of directional dominance are robust to model choice.

Meta-analytical estimates of effect size and standard errors are plotted for various models. Fixed indicates no mixed modelling was used, gr res indicates the GRAMMAR+ residuals were fitted and hglm indicates the full hierarchical generalised linear mixed model was used. + indicates the phenotype was rank transformed; FEV1 is forced expiratory lung volume in one second; Cognitive g is the general cognitive factor. 15,355 subjects were used for cognitive g, 36,060 for educational attainment, 89,112 for height and 15,262 for FEV1.

Extended Data Figure 7. Correlation in SROH for different genotyping arrays using HapMap populations.

In panels (a) – (c), X and Y axes show SROH (sum of runs of homozygosity) from 0-30 Mb (30,000 kb). ill370: Illumina CNV370, aff6: Affymetrix6, illomni: Illumina OmniExpress. The graphs are shown for the specific plink call parameters used. (d) Sample numbers per continent are presented in a bar chart. AFR: African, AMR: Mixed American, ASN: East Asian, EUR: European, SAN: South Asian. Only samples with SROH below 30 Mb are plotted, to be conservative to the effect of outliers, which have very strongly correlated estimates of SROH (r = 0.96-0.97 for comparisons including such very homozygous individuals). In these plots, the correlation between SROH called by the two arrays, r = 0.93-0.94.

Extended data Table 1. Continental ancestry of cohorts participating in each trait study.

The first number in each cell is the number of participants with that continental ancestry. The second number is the number of sub-cohorts. BP is blood pressure; FEV1 is forced expiratory lung volume in one second; FVC is forced vital lung capacity; FP is fasting plasma; HbA1c is haemoglobin A1c; HDL/LDL are High/low-density lipoprotein; g is the general cognitive factor (first unrotated principal component of test scores across diverse domains of cognition). S/C Asian is South & Central Asian.

| African | East Asian | European | Hispanic | S/C Asian | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 21689/15 | 29009/5 | 279400/117 | 7836/3 | 13464/10 | 351398/150 |

| Cognitive g | 1539/1 | NA/NA | 49559/22 | - | - | 51098/23 |

| Diastolic BP | 17074/12 | 24200/5 | 204742/85 | 7284/3 | 12876/9 | 266176/114 |

| Education Attained | 4811/4 | NA/NA | 79576/42 | - | 338/1 | 84725/47 |

| Fasting Insulin | 6895/8 | 1603/1 | 72006/49 | - | 6303/5 | 86807/63 |

| FEV1 | 6604/5 | 617/1 | 58089/27 | 825/1 | - | 66135/34 |

| FEVl/FVC | 6565/5 | 616/1 | 57888/27 | 822/1 | - | 65891/34 |

| FP Glucose | 8942/9 | 1615/1 | 122368/74 | 1938/1 | 6921/5 | 141784/90 |

| HbAlc | 6629/4 | 694/1 | 92732/31 | 4038/2 | 7509/4 | 111602/42 |

| HDL Cholesterol | 15099/13 | 10478/5 | 215621/92 | 4426/3 | 12508/9 | 258132/122 |

| Height | 20300/14 | 30011/5 | 281369/114 | 5469/2 | 13523/10 | 350672/145 |

| LDL Cholesterol | 13375/11 | 2503/2 | 172245/77 | 4340/3 | 11186/8 | 203649/101 |

| Systolic BP | 17023/12 | 24424/5 | 205253/85 | 7225/3 | 12859/9 | 266784/114 |

| Total Cholesterol | 15130/13 | 20187/5 | 209421/91 | 4491/3 | 11674/8 | 260903/120 |

| Triglycerides | 13886/12 | 2542/2 | 181526/84 | 2745/2 | 10688/7 | 211387/107 |

| Waist-hip ratio | 8182/7 | 2549/2 | 171753/73 | 1446/1 | 12598/9 | 196528/92 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in all ROHgen studies; cohort-specific acknowledgements are detailed in Supplementary Table 6. This work was funded by a UK Medical Research Council (MRC) PhD studentship to PKJ, and JFW and OP acknowledge support from the MRC Human Genetics Unit “QTL in Health and Disease” programme. We thank W.G. Hill for discussions and comments on the manuscript and K. Lindsay for administrative assistance.

Author contributions

CHal, PN, MMe, HB, NJS, DC, DAM, RSC, PF, GP, SFG, HH, LF, RAS, ADM, CNP, GDe, PD, LB, UL, SIB, CML, NJT, ATon, PBM, TIS, CNR, DKA, AJO, SLK, BB, GGa, APM, JGE, MJW, NGM, SCH, JMS, IJD, LRG, HT, NPi, JKa, NJW, LP, JGW, GGi, MJC, OR, DDB, CGi, Pv, AAH, PKr, JS, PKn, MJ, PKM, AH, RSc, IBB, EVa, DMB, DB, KLM, MB, CMvD, DKS, ATe, EZ, AMe, PG, SU, CO, DT, GDS, IR, DJP, MC, TDS, CHay, JD, RJL, AFW, GRC, PV, ASh, PMR, JIR, NS, UG, KEN, MP, BMP, DRW, MLa, VG, ATa, JCC, JSK, DPS, HC, JNH, MP, OP, JFW designed individual studies. TN, JDF, SE, VV, STr, DIC, SSN, MMa, DR, AF, LRY, EH, CBo, JRP, SC, UB, GM, TLi, ID, JZ, JPB, ES, SY, MAA, SJB, GRB, EPB, ACa, YChan, SJC, YDIC, FSC, JC, ACo, LCu, GDa, MD, SBE, BF, MFF, IF, CSF, TMF, NFri, FGe, IGi, OG, FGr, CGu, CJH, SEH, NDH, NLH, KH, LJH, GHo, PGH, EI, ÅJ, PJ, JJ, MKa, SK, SMK, NMK, HKK, MKu, JKu, JL, RAL, TLe, DCL, LLi, MLL, ALo, TLu, ALu, SM, KM, JBM, CMei, TM, CMen, FDM, LM, GWM, RHM, RN, MN, MSN, GTO, AO, SP, WRP, JSP, IPa, KP, NPo, SRa, PR, SSR, HR, AR, LMR, RR, BSa, RMS, VS, ASa, LJS, SSe, PS, BHS, NSor, ASttn, MGS, KS, NTa, KDT, BOT, ATog, MTo, JT, AGU, AvHV, TV, SV, EVl, EVu, MW, JBW, SW, GW, CSY, GZ, XZ, MMe, HB, NJS, DC, DAM, RSC, GP, SFG, HH, LF, RAS, GDe, PD, LB, UL, SIB, GDS, NJT, ATon, PBM, TIS, CNR, DKA, AJO, SLK, BB, MKK, GGa, JGE, MJW, NGM, SCH, JMS, IJD, LRG, JKa, NJW, LP, JGW, GGi, MJC, OR, DDB, CGi, Pv, AAH, PKr, JS, PKn, MJ, PKM, AH, RSc, IBB, EVa, DMB, DB, KLM, MB, CMvD, DKS, EZ, AMe, PG, CO, DT, DJP, MC, TDS, CHay, RJL, AFW, GRC, PV, ASh, PMR, JIR, NS, UG, MP, BMP, DRW, MLa, JCC, JSK, DPS, JNH, MP, OP, JFW collected the data. STr, DIC, MCC, CBo, UB, ID, MA, FWA, SJB, DJB, EB, EPB, ACc, SJC, JC, IF, TMF, CGu, CJH, TBH, NDH, MI, EI, JJ, PKo, MKu, LJL, RAL, LLi, RAM, KM, JBM, GWM, RHM, PAP, KP, SSR, RR, HS, PS, BHS, NSor, NSot, DVa, JBW, CSY, MMe, NJS, DC, DAM, RSC, PF, GP, SFG, HH, LF, GDe, PD, LB, UL, SIB, CML, ATon, PBM, CNR, DKA, AJO, SLK, BB, GGa, APM, MJW, NGM, SCH, JMS, IJD, LRG, JKa, NJW, LP, MJC, DDB, Pv, PKr, MJ, PKM, AH, RSc, IBB, DMB, DB, KLM, MB, CMvD, DKS, EZ, AMe, PG, SU, CO, IR, DJP, MC, TDS, CHay, AFW, GRC, PV, ASh, PMR, JIR, NS, UG, KEN, BMP, DRW, MLa, VG, DPS, HC, OP, JFW contributed to funding. PKJ, TE, HMa, NE, IGa, TN, AUJ, CSc, AVS, WZhan, YO, AStc, JDF, WZhao, TMB, MMC, NFra, SE, VV, STr, XG, DIC, JRO, TC, SSN, YChen, MMa, DR, MTa, AF, TKac, ABj, AvS, YW, AKG, LRY, LW, EH, CAR, OM, MCC, CP, NV, CBa, AAA, HRW, DVu, HMe, JRP, SSMi, MCB, SSMe, PAL, GM, AD, LY, LFB, DZ, PJv, DS, RM, GHe, TKar, ZW, TLi, ID, JZ, WM, LLa, SWvL, JPB, ARW, ABo, TSA, LMH, ES, SY, IMM, LCa, HGdH, MA, UA, NA, FWA, SEB, SB, ACa, YChan, CC, GDa, GE, BF, MFF, FGe, MG, SEH, JJH, JH, JEH, PGH, AJ, YK, SK, RAL, BL, MLo, SJLoo, YL, PM, AMa, CMen, FDM, EM, MEM, AMo, AO, IPa, FP, IPr, LMR, BSa, RMS, RSa, HS, WRS, CSa, CMa, BSe, SSh, SJLon, JAS, LS, RJS, MJS, STa, BOT, ATog, MTo, NTs, JvS, SV, DVo, EBW, WW, JY, GZ, NJS, RAS, ADM, CNP, SIB, NJT, APM, SCH, HT, NPi, LP, Pv, PKr, RSc, IBB, ATe, CO, MC, JD, JIR, NS, KEN, ATa, JCC, JSK, DPS analysed the data. PKJ, TE, HMa, NE, IGa, TN, AUJ, CSc, AVS, MCB, DPS performed beta-testing of scripts. PKJ and TE performed meta-analysis. PKJ, TE, OP and JFW wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature

Competing financial interests: GP is a co-founder of CAVADIS B.V. SWvL is a former employee of CAVADIS B.V. BMP serves on the Data and Safety Monitoring Board of a clinical trial funded by the manufacturer (Zoll Lifecor) and on the Yale Open Data Access Project funded by Johnson & Johnson. NPo has received financial support and consultancy fees from several pharmaceutical companies that manufacture either blood-pressure-lowering or lipid-lowering agents or both. PS has received research awards from Pfizer. No other authors declared a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Garrod A. The incidence of alkaptonuria: a study of chemical individuality. Lancet. 1902;11:1616–1620. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darwin C. The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. Appleton: 1868. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McQuillan R, et al. Runs of Homozygosity in European Populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;83:359–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McQuillan R, et al. Evidence of Inbreeding Depression on Human Height. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudan I, et al. Inbreeding and the Genetic Complexity of Human Hypertension. Genetics. 2003;163:1011–1021. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.3.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell H, et al. Effects of genome-wide heterozygosity on a range of biomedically relevant human quantitative traits. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:233–241. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charlesworth D, Willis JH. The genetics of inbreeding depression. Nature Rev. Genetics. 2009;10:783–796. doi: 10.1038/nrg2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright S. Evolution and the Genetics of Populations, Vol. 3: Experimental Results and Evolutionary Deductions. University of Chicago Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright S. Coefficients of inbreeding and relationships. Am. Nat. 1922;56:330–339. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broman KW, Weber JL. Long Homozygous Chromosomal Segments in Reference Families from the Centre d’Étude du Polymorphisme Humain. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;65:1493–1500. doi: 10.1086/302661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson J, Morton NE, Collins A. Extended tracts of homozygosity in outbred human populations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:789–795. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirin M, McQuillan R, Franklin CS, Campbell H, McKeigue PM, Wilson JF. Genomic Runs of Homozygosity Record Population History and Consanguinity. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller MC, Visscher PM, Goddard ME. Quantification of Inbreeding Due to Distant Ancestors and Its Detection Using Dense Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Data. Genetics. 2011;189:237–249. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pemberton TJ, Rosenberg NA. Population-genetic influences on genomic estimates of the inbreeding coefficient: a global perspective. Hum Hered. 2014;77:37–48. doi: 10.1159/000362878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdellaoui A, et al. Educational Attainment Influences Levels of Homozygosity through Migration and Assortative Mating. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0118935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neel JV, Schull WJ, Yamamoto M, Uchida S, Yanase T, Fujiki N. The effects of parental consanguinity and inbreeding in Hirado, Japan. II. Physical development, tapping rate, blood pressure, intelligence quotient, and school performance. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1970;22:263–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marioni RE, et al. Common genetic variants explain the majority of the correlation between height and intelligence: the generation Scotland study. Behav. Genet. 2014;44:91–96. doi: 10.1007/s10519-014-9644-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood AR, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nature Genet. 2014;46:1173–86. doi: 10.1038/ng.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deary IJ, et al. Genetic contributions to stability and change in intelligence from childhood to old age. Nature. 2012;482:212–215. doi: 10.1038/nature10781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morton NE. Effect of inbreeding on IQ and mental retardation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1978;75:3906–3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Najmabadi H, et al. Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature. 2011;478:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nalls MA, et al. Measures of Autozygosity in Decline: Globalization, Urbanization, and Its Implications for Medical Genetics. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flynn JR. Massive IQ gains in 14 nations: what IQ tests really measure. Psychol. Bull. 1987;101:171–191. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galton F. Natural inheritance. MacMillan; London: 1889. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman JI, et al. High-throughput sequencing reveals inbreeding depression in a natural population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:3775–3780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318945111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright A, Charlesworth B, Rudan I, Carothers A, Campbell H. A polygenic basis for late-onset disease. Trends Genet. 2003;19:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss L.A, Pan, L., Abney M, Ober C. The sex-specific genetic architecture of quantitative traits in humans. Nature Genet. 2006;38:218–222. doi: 10.1038/ng1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powell JE, et al. Congruence of Additive and Non-Additive Effects on Gene Expression Estimated from Pedigree and SNP Data. PLoS Genet. 2014;9:e1003502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller MC, et al. Runs of Homozygosity Implicate Autozygosity as a Schizophrenia Risk Factor. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darwin C. The Effects of Crossing and Self Fertilization in the Vegetable Kingdom. John Murray; 1876. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purcell S. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aulchenko YS, Ripke S, Isaacs A, van Duijn CM. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1294–1296. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ronnegard L, Shen X, Alam M. hglm: A Package for Fitting Hierarchical Generalized Linear Models. The R Journal. 2010;2:20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lango Allen H, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467:832–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ehret GB, et al. Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature. 2011;478:103–109. doi: 10.1038/nature10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott RA, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nature Genetics. 2012;44:991–1005. doi: 10.1038/ng.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willer CJ, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nature Genetics. 2013;45:1274–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soler Artigas M, et al. Genome-wide association and large-scale follow up identifies 16 new loci influencing lung function. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:1082–1090. doi: 10.1038/ng.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rietveld CA, et al. GWAS of 126,559 individuals identified genetic variants associated with educational attainment. Science. 2013;340:1467–1471. doi: 10.1126/science.1235488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stefansson H, et al. CNVs conferring risk of autism or schizophrenia affect cognition in controls. Nature. 2014;505:361–366. doi: 10.1038/nature12818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.1000 Genomes Project An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aulchenko YS, de Koning DJ, Haley C. Genomewide rapid association using mixed model and regression: a fast and simple method for genome-wide pedigree-based quantitative trait loci association analysis. Genetics. 2007;177:577–85. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.075614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marioni RE, et al. Molecular genetic contributions to socioeconomic status and intelligence. Intelligence. 2014;44:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Academic Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.