Abstract

Background

For patients with unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), treatment options are limited and survival is poor. This study summarizes the long-term outcome of two previously reported clinical trials using hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) with floxuridine and dexamethasone (with or without bevacizumab) in advanced ICC.

Methods

Prospectively collected clinicopathologic and survival data were retrospectively reviewed. Response was based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). Pre-HAI dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) images were reviewed, and tumor perfusion data correlated with outcome.

Results

Forty-four patients were analyzed (floxuridine, 26; floxuridine/bevacizumab, 18). At a median follow-up of 29.3 months, 41 patients had died of disease. Partial response by RECIST was observed in 48 %, and 50 % had stable disease. Three patients underwent resection after response, and 82 % received additional HAI after removal from the trials. Median survival was similar in both trials (floxuridine 29.3 months vs. floxuridine/bevacizumab 28.5 months; p = 0.96). Ten (23 %) patients survived ≥3 years, including 5 (11 %) who survived ≥5 years. Tumor perfusion measured on pre-treatment DCE-MRI [area under the gadolinium concentration curve at 90 and 180 s (AUC90 and AUC180, respectively)] was significantly higher in ≥3-year survivors and was the only factor that distinguished this group from <3-year survivors (mean AUC90 22.6 vs. 15.9 mM s, p = 0.025, and mean AUC180 48.9 vs. 32.3 mM s, p = 0.003, respectively). Median hepatic progression-free survival was longer in ≥3-year survivors (12.9 vs. 9.3 months, respectively; p = 0.008).

Conclusions

HAI chemotherapy can result in prolonged survival in unresectable ICC. Pre-HAI DCE-MRI may predict treatment outcome.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) represents the second most common primary liver cancer, and is increasing in frequency and mortality. The minority of patients present with resectable disease, with little change over the last 3 decades.1–3 Response to systemic chemotherapy has been poor, and although gemcitabine plus cisplatin was recently shown to be the most active regimen in patients with advanced biliary cancer, median survival remains less than 1 year.4

Hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) chemotherapy for liver cancer has been used for over 50 years5 and is based on enhanced drug delivery to the tumor while minimizing systemic toxicity. Although most published studies have focused on its application in colorectal liver metastases,6–8 results in primary liver cancer are encouraging. We have previously published the results of two phase II clinical trials on HAI for unresectable primary liver cancer using floxuridine either alone or in combination with intravenous bevacizumab.9,10 Both studies were associated with prolonged liver disease control and median survival rates of 29.5 and 31.1 months. Additionally, dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) showed promise as an imaging biomarker of treatment response. Specifically, integrated area under the concentration curve of gadolinium contrast at 90 and 180 s (AUC90 and AUC180, respectively), an assessment of perfusion, was associated with higher response rates and significantly longer survival.9,10

This study updates the long-term outcome of patients with unresectable ICC treated with HAI chemotherapy as part of these two clinical trials, and analyzes the clinicopathologic characteristics associated with prolonged disease control and survival.

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). Only patients with unresectable ICC treated with floxuridine, with or without intravenous bevacizumab as part of two phase II clinical trials conducted from August 2003 through September 2009, were included. Clinicopathologic data, prospectively collected during the clinical trials, were analyzed (26 patients from the floxuridine study and 18 patients from the floxuridine/bevacizumab study). Patients from both studies were combined since there were no differences in demographics, selection criteria, tumor characteristics, response, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival between the two groups. Patient selection, exclusionary factors, and pre-treatment evaluation have been previously reported.9,10 Pump placement was performed with a standardized technique.11

Chemotherapy Administration, Response, Dose Intensity, and Toxicity

HAI chemotherapy was started 2 weeks after pump placement, on a 4-week cycle, and consisted of floxuridine for 26 patients and floxuridine/bevacizumab for 18 patients. Infusion of floxuridine (0.16 mg/kg × 30/pump flow rate) and dexamethasone 25 mg, with heparin sulfate (30,000 units) and saline to a volume of 30 mL, was started on day 1 for 14 days; bevacizumab (5 mg/kg) was given every other week, starting 6 weeks after surgery. Concurrent cytotoxic systemic chemotherapy was not used while patients were on study, but was used after disease progression, either alone or in combination with further floxuridine. Floxuridine relative dose intensity was measured at 3 and 6 months from the beginning of HAI treatment. Relative dose intensity is the amount of chemotherapy given over time divided by the calculated dose at the beginning of therapy, and accounts for toxicity-related dose reductions or missing doses, altering the total amount of administered chemotherapy.12

Prior to treatment, imaging evaluation included baseline liver MRI scans, including dynamic sequences, and computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest and pelvis. MRI scans were repeated every 2 months while on protocol; response to therapy was assessed with the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.0).13 DCE-MRI scans were obtained using a 1.5 T MRI scanner (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA) and an 8-channel phased array body coil using previously described MRI parameters and contrast infusion.14 Anatomical images, fat-suppressed T1- and T2-weighted images, three-dimensional T1-weighted pre- and post-contrast images, and fast gradient echo-based perfusion images were acquired during each scan. Intravenous contrast (gadolinium diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid; Magnevist, Berlex Inc., Wayne, NJ, USA) was administered at a constant dose of 0.1 mmol/kg bodyweight. A bolus of gadolinium was injected with a delay of 6 s using an automatic injector (Medrad, Inc., Warrendale, PA, USA), and serial images with a temporal resolution of 1.2–1.5 s were acquired over 4–5 min under shallow breathing conditions. One coronal oblique plane was prescribed through the center of the tumor and the aorta to maximize the cross-sectional area and the temporal resolution. DCE-MRI parameters included the following: echo time (TE) = 2 ms, repetition time (TR) = 9 ms, flip angle = 30°, slice thickness = 7 mm, matrix size = 256 × 128, field of view = 320 mm, bandwidth = 23.8 kHz, number of excitations = 1.0, and number of phases (n) = 225. Dynamic images were analyzed with a two-compartment general kinetic model using a vascular space (VS) and an extracellular extravascular space (EES) for pharmacokinetic characterization of tumors.15 The vascular input function (VIF) was measured in some patients, and an average VIF with two fast and slow components16 was used for analysis (Cine Research Software, GEMS, Waukesha, WI, USA) of the dynamic and pharmacokinetic parameters. The variables measured included (i) those related to tumor permeability—the volume transfer constant (Ktrans, 1/min) from VS to EES, the rate constant (Kep, 1/min) from EES to VS, and the fractional volume of EES (ve); and (ii) those related to global tumor perfusion—the integrated AUC90 and AUC180 from the start of contrast enhancement (mM s).17 In each case, the region of interest (ROI) and voxel (Vx) analyses were carried out for determining the kinetic parameters in tumors. For the Vx analyses, the top decile values within the ROI were determined for the variables of interest. The change in DCE-MRI parameters from baseline to the first post-treatment scan was also determined using both ROI and Vx values.

The pre-treatment DCE-MRI parameters were correlated with response and survival. All patients had multiple post-treatment follow-up DCE-MRI studies in both trials, and the changes in DCE-MRI parameters following treatment were previously reported.9,18 However, for this study, we wanted to look exclusively at patients with unresectable cholangiocarcinoma with similar pre-treatment DCE-MRI, and avoid combining the results related to changes in DCE-MRI parameters since they were induced by two different therapeutic regimens and their timing was different between the two studies. In addition, as we previously reported, disease-specific survival (DSS) in patients undergoing treatment for primary liver cancer was significantly correlated with pre-treatment AUC90 and AUC180. The reproducibility rate of DCE-MRI measurements is in the range of 10–20 %.19

Toxicity was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 3.0).20 Treatment-related toxicity 10 was analyzed for its impact on survival.

DSS and progression free survival (PFS) were measured from the date of HAI treatment initiation until death or last follow-up and first documented progression, respectively.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 20.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA); p values < 0.05 were considered significant. Descriptive statistics are presented as means (standard deviation) for continuous variables, and percentages for categorical variables. Survival data are reported as median values (range). Continuous variables were compared using Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis tests. Categorical variables were compared using Chi square and Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Survival was measured from initiation of HAI. Survival probabilities were computed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test.

Results

Clinicopathologic Characteristics

Table 1 details the patient characteristics. Mean age was 59 years (±13.2) and 31 (70 %) patients were female. Mean tumor size was 9.3 cm (±3.4), and the majority were solitary (68 %) and moderately differentiated (74 %). Eleven (25 %) patients had undergone treatment prior to trial enrollment, most commonly systemic chemotherapy; three (7 %) patients had undergone a prior resection with curative intent and had liver-only recurrence.

Table 1. Clinicopathologic data of 44 patients with unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

| Factor | N = 44 (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, years | 59 (13.2) |

| Male gender | 13 (30) |

| KPS | 79.2 |

| Tumor size, cm (range) | 9.3 (2.1–16.4) |

| Single tumor | 30 (68) |

| Histologic grade | 35 (80) |

| Well | 1 (3) |

| Moderately | 26 (74) |

| Poorly | 8 (23) |

| Pretrial treatment | 11 (25) |

| Systemic chemotherapy | 7 (16) |

| Gemcitabine/capecitabine | 2 (29) |

| Gemcitabine/cisplatin | 1 (14) |

| Gemcitabine | 1 (14) |

| Carboplatin/docetaxel/bevacizumab | 1 (14) |

| More than one chemotherapy linea | 2 (29) |

| Resection | 3 (7) |

| Ablation/chemoembolization | 2 (5) |

KPS Karnofsky performance status

One patient received gemcitabine/cisplatin then irinotecan/capecitabine, followed by 5-fluoruracil/erlotinib; one patient received gemcitabine/carboplatin/paclitaxel then irinotecan, followed by 5-fluoruracil/oxaliplatin

Trial-Related Treatment and Toxicity

Table 2 summarizes treatment administered as part of the clinical trials. HAI was started at a mean of 14.7 days (±2.4) from pump placement for all patients. The relative floxuridine dose intensity was 82 % at 3 months (similar for both trials) and 57 % at 6 months (greater for floxuridine vs. floxuridine/bevacizumab; 64 vs. 48 %; p = 0.04).

Table 2. Trial-related treatment and toxicity.

| Treatment | N = 44 (%) |

|---|---|

| Agent | |

| FUDR | 26 (59) |

| FUDR/bevacizumab | 18 (41) |

| Time to treatment initiation (days)a | 14.7 (2.4) |

| Relative dose intensity (±SD) | |

| 3 months | 0.82 ± 0.19 |

| 6 months | 0.57 ± 0.21 |

| Postoperative complicationsb | 6 (14) |

| FUDR | 3 (7) |

| Cellulitis | 1 (33) |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 1 (33) |

| Pump misperfusion/embolization | 1 (33) |

| FUDR/bevacizumab | 3 (7) |

| Wound infection | 1 (33) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 (33) |

| Infection at pump/replacement | 1 (33) |

| Chemotherapy toxicity grade 3/4 | 10 (23) |

| Bilirubin ≥ 2 mg/dL | 6 (14) |

| Bilirubin > 3 mg/dL | 3 (7) |

| Biliary stent | 3 (7) |

| SGOT | 4 (9) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 1 (2) |

| Syncope | 1 (2) |

| Confusion | 2 (5) |

| Thrombosis | 1 (2) |

| Duodenal tear | 1 (2) |

| Hyperglycemia | 1 (2) |

FUDR floxuridine, SD standard deviation, SGOT serum glutamicoxaloacetic transaminase

From pump placement

Related to pump placement

Postoperative complications related to pump placement occurred in six (14 %) patients, three in each trial; however, all patients received HAI therapy without delay in treatment initiation (14.7 days for floxuridine vs. 14.9 days for floxuridine/bevacizumab; p = 0.97). Grade 3/4 toxicity occurred in ten patients, mostly biliary toxicity related to the floxuridine/bevacizumab trial. The excessive toxicity associated with the addition of bevacizumab to floxuridine led to early termination of this trial.10

Response, Pattern of Progression, Post-Trial Treatment, and Survival

Twenty-one (48 %) patients had a partial response over a median time of 11.4 months (range 3.2–37.9 months) and 22 (50 %) had stable disease over a median of 7 months (range 2–11 months); disease control rate was 98 % (median 8 months; range 1.4–37.9). Initial disease progression was in the liver in 24 (55 %) patients, at extrahepatic sites for 19 (43 %) patients, and both in one (2 %) patient (Table 3). Eight patients progressed while HAI therapy was on hold.

Table 3. Response, pattern of disease progression, and post-trial treatments.

| Treatment | N = 44 (%) |

|---|---|

| Response (RECIST) | |

| Partial | 21 (48) |

| Stable disease | 22 (50) |

| Disease progression | 1 (2) |

| DCE-MRI | |

| Tumor permeability markers | |

| Ktrans (min−1) | 1.47 (1.36) |

| Kep (min−1) | 4 (3) |

| Global tissue perfusion markers | |

| AUC90 (mM s) | 17.2 (7.2) |

| AUC180 (mM s) | 35.6 (15) |

| Initial sites of disease progression | |

| Liver | 24 (55) |

| Extrahepatic site | 19 (43) |

| Both | 1 (2) |

| Post-trial liver-directed treatment | 38 (86) |

| Hepatic arterial infusion | 36 (82) |

| Floxuridine | 18 (41) |

| Floxuridine/mitomycin | 19 (43) |

| Gemcitabine | 4 (9) |

| None | 8 (18) |

| Resection | 3 (7) |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 1 (2) |

| Hepatic artery embolization | 2 (5) |

| External beam radiation | 1 (2) |

| Post-trial systemic chemotherapy | 42 (95) |

| Gemcitabine | 38 (86) |

| Irinotecan | 26 (59) |

| 5-Fluoruracila | 24 (55) |

| Oxaliplatin | 14 (32) |

| Bevacizumab | 6 (14) |

| Other agentsb | 9 (20) |

| Other treatments | |

| Lung resection | 1 (2) |

| Median survival | |

| 3-year survivors | 10 (23) |

| 5-year survivors | 5 (11) |

Including oral capecitabine

Sorafenib, 2; docetaxel/paclitaxel, 2; veliparib (PARP inhibitor), 1; carboplatin/cisplatin, 3; flavopiridol (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor), 1; vorinostat (histone deacetylase inhibitor), 1; 17AAG (heat shock protein 90 inhibitor), 1; AZD 7762 (checkpoint kinase inhibitor), 1; DS 7423 (PI3 K/mTOR kinase inhibitor), 1; cetuximab, 1

Treatments administered after removal from the trials are shown in Table 3. Thirty-six (82 %) patients received additional HAI, either alone or concurrently with systemic chemotherapy. Systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy was eventually given to 42 (95 %) patients, with the most frequently administered agent being gemcitabine. Three (7 %) patients showed enough response to undergo hepatic resection (floxuridine, 1; floxuridine/bevacizumab, 2).

All patients, except three in the floxuridine/bevacizumab study, were deceased at the time of last follow-up. The median survival from initiation of HAI was 29.3 months (95 % CI 26.6–31.9 months) and was similar between the two trials (floxuridine 29.3 vs. floxuridine/bevacizumab 28.5 months; p = 0.96). Ten (23 %) patients survived 3 years or more and five (11 %) patients survived at least 5 years; the proportion of long-term survivors (≥3 years) was similar in both clinical trials.

Comparison of Long-Term and Short-Term Survivors

Comparison of long-term (≥3 years) and short-term (<3 years) survivors is summarized in Table 4. There were no differences in patient demographics, disease characteristics, or pre-trial, within-trial, and post-trial treatments rendered. The pre-treatment mean carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) values were not significantly different between ≥ 3-year and < 3-year survivors (CA19-9: 48 vs. 759 U/ml, p = 0.2; and CEA 2.1 vs. 15.4 ng/ml, p = 0.1, respectively). The relative HAI dose intensity at 6 months from the initiation of HAI was similar between the two groups, as was the proportion of grade 3 or 4 toxicity. Response rates were similar between the two groups.

Table 4. Comparison of 3-year (≥3-year) survivors to less than 3-year (< 3-year) survivors.

| Factors | ≥3-year survivors [n = 10] (%) | <3-year survivors [n = 34] (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 55.4 ± 10 | 60 ± 13.9 | 0.28 |

| Male gender | 2 (20) | 11 (32) | 0.69 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 9.2 ± 2.9 | 9.4 ± 3.5 | 0.67 |

| Single tumor | 7 (70) | 25 (74) | 1 |

| Tumor differentiation | 8 (80) | 27 (79) | 0.6 |

| Well | 0 | 1 (4) | |

| Moderately | 1 (13) | 19 (70) | |

| Poorly | 7 (87) | 7 (26) | |

| Pre-HAI chemotherapy | 1 (10) | 5 (15) | 1 |

| Pre-HAI MRI | |||

| Mean AUC90 (mM s) | 22.6 ± 7.8 | 15.9 ± 6.6 | 0.02 |

| Mean AUC180 (mM s) | 48.9 ± 13.3 | 32.3 ± 13.7 | 0.003 |

| Treatment in trial | 0.49 | ||

| Floxuridine | 7 | 19 | |

| Floxuridine/bevacizumab | 3 | 15 | |

| HAI response (RECIST) | 7 (70) | 14 (41) | 0.1 |

| Grade 3 or 4 toxicity | 1 (10) | 9 (26) | 0.26 |

| Floxuridine relative dose intensity (6 months) | 0.63 ± 0.25 | 0.56 ± 0.2 | 0.48 |

| Disease progression extrahepatic | 3 (30) | 15 (44) | 0.49 |

| Hepatic progression-free survival (months) | 12.9 | 9.3 | 0.008 |

| Post-trial HAI | 8 (80) | 27 (79) | 1 |

| Post-trial systemic chemotherapy | 9 (90) | 33 (97) | 0.4 |

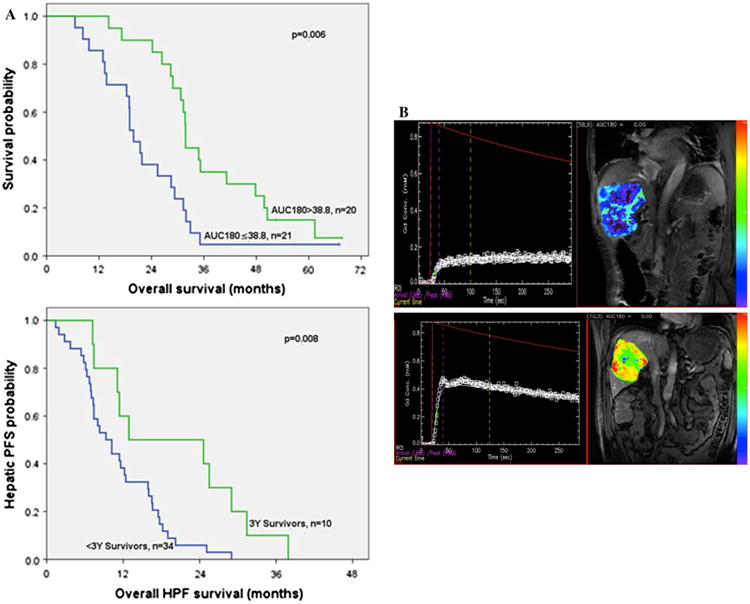

Data from DCE-MRI were available in 41 (93 %) patients (one patient had a pacemaker and two had incomplete dynamic series). Pre-treatment AUC180 was higher in long-term versus short-term survivors (48.9 ± 13.3 vs. 32.3 ± 13.7 mM s; p = 0.003); in patients with an AUC180 above the median value (38.8 mM s), survival was greater compared with those with an AUC180 equal to or below the median (31.8 vs. 19.9 months, p = 0.006, respectively; Fig. 1a). Similar findings were observed for patients with AUC90 above or below the median (AUC90 17.06 mM s) (31.8 vs. 21.8 months, respectively; p = 0.007). In patients with AUC180 above the median value, 35 % survived beyond 3 years, while 95 % of patients with AUC180 below the median survived less than 3 years. Of note, none of the other DCE-MRI parameters (Ktrans, Kep) were different between the two groups. Long-term survivors were also characterized by a longer hepatic PFS (12.9 vs. 9.3 months; p = 0.008; Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a Survival curves. Overall survival in patients with AUC180 above or below the median value and HPF in 3-year versus <3-year survivors. b Pre-HAI DCE-MRI with low AUC curve of gadolinium and corresponding MRI showing poor contrast enhancement in a <3-year survivor, and high AUC curve of gadolinium and corresponding MRI showing greater contrast enhancement in a ≥3-year survivor

It should be noted that while the DCE-MRI variables AUC90 and AUC180 were associated with survival (r2 = 0.45 for AUC90, p = 0.003; r2 = 0.48 for AUC180, p = 0.001), there was no correlation with response as measured by RECIST; the percentage of maximal tumor reduction after initiation of HAI did not correlate with survival (r2 = 0.14; p = 0.4).

Discussion

The incidence of ICC is rising worldwide, and most patients present with unresectable disease.21 Advanced ICC is associated with a dismal prognosis and even the best multiagent systemic chemotherapy regimen does not prolong survival beyond 1 year.4,22–24 Furthermore, to date, targeted therapies have not shown a benefit and have no proven therapeutic role.3 More effective therapeutic approaches are thus needed.

Chemotherapy delivered via continuous HAI is an attractive therapeutic approach for several reasons. First, it allows delivery of high concentrations of chemotherapy into the hepatic arterial system, from which the tumor derives nearly all of its blood supply. In so doing, non-target toxicity is reduced, although not eliminated. Using an agent with a favorable first-pass profile such as floxuridine with a liver extraction rate of 94 % makes this strategy even more appealing.10,25

The body of literature related to the use of palliative HAI chemotherapy is greatest for metastatic colorectal cancer, where it has proven efficacy for controlling hepatic disease.8,26,27 By contrast, the experience with HAI chemotherapy in primary liver cancer is limited.28,29 Our previously reported experience with HAI for unresectable primary liver cancer demonstrated the efficacy of HAI with floxuridine in patients with advanced ICC.9,10 The present study represents a long-term survival analysis of patients from both studies.

A major finding of the present study was identification of a subgroup of ICC patients who survived 3 or more years from the start of therapy, well beyond what has been reported with systemic therapy alone. Examining the long-term and short-term survivors revealed no differences in patient demographics, and disease- or treatment-related variables. Indeed, the only variable that distinguished these two groups were tumors with higher pre-HAI AUC90 and AUC180 on DCE-MRI and longer hepatic PFS. This latter finding underscores the importance of control of the hepatic disease on outcome.

Our initial experience with DCE-MRI in patients with primary liver cancer using floxuridine alone9 showed that pre-treatment assessment of tumor perfusion, as measured by AUC at 90 and 180 s from the start of contrast enhancement, correlated with improved survival. The results of the present study confirmed these findings in longer follow-up. Patients who survived 3 or more years had higher AUC values at 90 and 180 s; the longer hepatic PFS in this group would suggest that these DCE-MRI variables, which represent a global assessment of tumor perfusion (Fig. 1b), have the potential to identify patients who benefit more from intra-arterial therapy. The absence of a correlation between the DCE-MRI and response as measured by RECIST is compatible with this observation and has been noted.30 Tumor response to therapy is difficult to fully characterize with size change alone, and it is well-established that RECIST is suboptimal in this regard, since it does not account for changes in tumor perfusion or necrosis,31,32 which may offer more insight.

Although differences were observed in global perfusion (AUC90 and AUC180), the lack of differences in perfusion and permeability parameters (Ktrans, Kep) between the short-term and long-term survivors requires further study. Higher perfusion in tumors compared with surrounding liver parenchyma may be dominating the permeability components of the measurements. Calculation of AUC is independent, while Ktrans and Kep depend on complex pharmacokinetic modeling, which may have been limited by the DCE-MRI technique and analyses performed. Future studies will use parameters according to recently emerging standardized guidelines for DCE-MRI by the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) and Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance (QIBA).

Whether higher pre-HAI AUC90 and AUC180 values reflect tumors with more favorable biology or a micro-vasculature that is more favorably predisposed to intra-arterial therapy is unclear. Data from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with systemic therapy suggest a potential role for DCE-MRI that is independent of treatment modality.31,32 Additionally, a prior study of resected ICC demonstrated improved disease-free survival in patients with arterially enhancing tumors compared with those with hypovascular tumors on CT.33 In this study, tumor vascularity was based on CT imaging and not DCE-MRI, and the authors defined an arbitrary dichotomy of hypervascular and hypovascular tumors. While CT and dynamic MRI perfusion parameters have some differences, it is possible that a CT perfusion technique can provide similarly quantitative tumor perfusion data.

The combination of HAI with systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy is likely to offer better overall disease control. Such combination therapy for colorectal liver metastases achieves substantial response and survival rates in patients with unresectable disease26,27 and high conversion to resectability.34 Existing trials on combination of HAI and systemic chemotherapy for advanced ICC are small and heterogeneous, but the results are encouraging.35,36 The majority of patients in the present study received both HAI and systemic chemotherapy during their treatment, and although it is impossible to know the individual contributions of each to the prolonged survival rates observed, it is reasonable to speculate that the combination may act synergistically and therefore merits further investigation.

Certain limitations of this study and of HAI therapy must be acknowledged. First, the data were combined from two clinical trials, but we believe that this was reasonable and valid statistically for several reasons. Most importantly, the level of heterogeneity between the groups was low—all patients were treated by the same group over a relatively short period of time, and patient demographics, selection criteria, and the regional chemotherapy administered were similar in both trials.10 Furthermore, although one of the studies included the use of bevacizumab, the response, PFS, and overall survival were nearly identical between the two. Additionally, the DCE-MRI acquisition and the image analysis methods were identical between the two studies, and only the pre-HAI studies were used for analysis. It is important to emphasize that pump placement is an invasive procedure, associated with potential complications, and HAI therapy itself can induce biliary toxicity, a problem that may be exacerbated with the addition of certain systemic agents; 10,11,37 however, neither of these factors limited the relative dose intensity of the therapy rendered.

Conclusions

The data from this study show that HAI provides an opportunity for prolonged survival in selected patients with unresectable ICC. Pre-HAI evaluation with DCE-MRI might help identify the patients who will benefit most from HAI. Clinical trials examining combination therapy with HAI and best systemic chemotherapy are warranted in order to make further progress with this disease.

Acknowledgments

NIH P30 CA008748, Cancer Center Support Grant.

Footnotes

This work was presented as a poster at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 50th Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 31 May– 4 June 2013.

References

- 1.Khan SA, Thomas HC, Davidson BR, Taylor-Robinson SD. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1303–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24(2):115–25. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel T. Cholangiocarcinoma: controversies and challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8(4):189–200. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1273–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan RD, Norcross JW, Watkins E., Jr Chemotherapy of metastatic liver cancer by prolonged hepatic-artery infusion. N Engl J Med. 1964;270:321–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196402132700701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kemeny N, Huang Y, Cohen AM, Shi W, Conti JA, Brennan MF, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of chemotherapy after resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(27):2039–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.House MG, Kemeny NE, Gonen M, Fong Y, Allen PJ, Paty PB, et al. Comparison of adjuvant systemic chemotherapy with or without hepatic arterial infusional chemotherapy after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2011;254(6):851–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822f4f88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kemeny NE, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis DR, Lenz HJ, Warren RS, Naughton MJ, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion versus systemic therapy for hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a randomized trial of efficacy, quality of life, and molecular markers (CALGB 9481) J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(9):1395–403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.8166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarnagin WR, Schwartz LH, Gultekin DH, Gonen M, Haviland D, Shia J, et al. Regional chemotherapy for unresectable primary liver cancer: results of a phase II clinical trial and assessment of DCE-MRI as a biomarker of survival. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(9):1589–95. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kemeny NE, Schwartz L, Gonen M, Yopp A, Gultekin D, D'Angelica MI, et al. Treating primary liver cancer with hepatic arterial infusion of floxuridine and dexamethasone: does the addition of systemic bevacizumab improve results? Oncology. 2011;80(3–4):153–9. doi: 10.1159/000324704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen PJ, Nissan A, Picon AI, Kemeny N, Dudrick P, Ben-Porat L, et al. Technical complications and durability of hepatic artery infusion pumps for unresectable colorectal liver metastases: an institutional experience of 544 consecutive cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyman GH. Impact of chemotherapy dose intensity on cancer patient outcomes. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2009;7(1):99–108. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(3):205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lockhart AC, Rothenberg ML, Dupont J, Cooper W, Chevalier P, Sternas L, et al. Phase I study of intravenous vascular endothelial growth factor trap, aflibercept, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):207–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kety SS. The theory and applications of the exchange of inert gas at the lungs and tissues. Pharmacol Rev. 1951;3(1):1–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinmann HJ, Laniado M, Mutzel W. Pharmacokinetics of GdDTPA/dimeglumine after intravenous injection into healthy volunteers. Physiol Chem Phys Med NMR. 1984;16(2):167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tofts PS, Brix G, Buckley DL, Evelhoch JL, Henderson E, Knopp MV, et al. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T(1)-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;10(3):223–32. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199909)10:3<223::aid-jmri2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yopp AC, Schwartz LH, Kemeny N, Gultekin DH, Gonen M, Bamboat Z, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy for primary liver cancer: correlation of changes in dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with tissue hypoxia markers and clinical response. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(8):2192–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1570-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng CS, Raunig DL, Jackson EF, Ashton EA, Kelcz F, Kim KB, et al. Reproducibility of perfusion parameters in dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of lung and liver tumors: effect on estimates of patient sample size in clinical trials and on individual patient responses. AJR. 2010;194(2):W134–40. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Cancer Institute. Common terminology criteria for adverse events v3.0 (CTCAE) [Accessed 9 Aug 2006]; http://ctepcancergov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3pdf.

- 21.Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33(6):1353–7. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ducreux M, Van Cutsem E, Van Laethem JL, Gress TM, Jeziorski K, Rougier P, et al. A randomised phase II trial of weekly high-dose 5-fluorouracil with and without folinic acid and cisplatin in patients with advanced biliary tract carcinoma: results of the 40955 EORTC trial. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(3):398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kornek GV, Schuell B, Laengle F, Gruenberger T, Penz M, Karall K, et al. Mitomycin C in combination with capecitabine or biweekly high-dose gemcitabine in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer: a randomised phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(3):478–83. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson CD, Pinson CW, Berlin J, Chari RS. Diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2004;9(1):43–57. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-1-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ensminger WD, Rosowsky A, Raso V, Levin DC, Glode M, Come S, et al. A clinical-pharmacological evaluation of hepatic arterial infusions of 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine and 5-fluorouracil. Cancer Res. 1978;38(11 Pt 1):3784–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemeny N, Gonen M, Sullivan D, Schwartz L, Benedetti F, Saltz L, et al. Phase I study of hepatic arterial infusion of floxuridine and dexamethasone with systemic irinotecan for unresectable hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(10):2687–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.10.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ducreux M, Ychou M, Laplanche A, Gamelin E, Lasser P, Husseini F, et al. Hepatic arterial oxaliplatin infusion plus intravenous chemotherapy in colorectal cancer with inoperable hepatic metastases: a trial of the gastrointestinal group of the Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):4881–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamashita T, Arai K, Sunagozaka H, Ueda T, Terashima T, Yamashita T, et al. Randomized, phase II study comparing interferon combined with hepatic arterial infusion of fluorouracil plus cisplatin and fluorouracil alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2011;81(5–6):281–90. doi: 10.1159/000334439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woo HY, Bae SH, Park JY, Han KH, Chun HJ, Choi BG, et al. A randomized comparative study of high-dose and low-dose hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for intractable, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;65(2):373–82. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Bruyne S, Van Damme N, Smeets P, Ferdinande L, Ceelen W, Mertens J, et al. Value of DCE-MRI and FDG-PET/CT in the prediction of response to preoperative chemotherapy with bevacizumab for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(12):1926–33. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S, Amadori D, Santoro A, Figer A, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(26):4293–300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abou-Alfa GK, Johnson P, Knox JJ, Capanu M, Davidenko I, Lacava J, et al. Doxorubicin plus sorafenib vs doxorubicin alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(19):2154–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SA, Lee JM, Lee KB, Kim SH, Yoon SH, Han JK, et al. Intrahepatic mass-forming cholangiocarcinomas: enhancement patterns at multiphasic CT, with special emphasis on arterial enhancement pattern–correlation with clinicopathologic findings. Radiology. 2011;260(1):148–57. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kemeny NE, Melendez FD, Capanu M, Paty PB, Fong Y, Schwartz LH, et al. Conversion to resectability using hepatic artery infusion plus systemic chemotherapy for the treatment of unresectable liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3465–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cantore M, Mambrini A, Fiorentini G, Rabbi C, Zamagni D, Caudana R, et al. Phase II study of hepatic intraarterial epirubicin and cisplatin, with systemic 5-fluorouracil in patients with unresectable biliary tract tumors. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1402–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mambrini A, Guglielmi A, Pacetti P, Iacono C, Torri T, Auci A, et al. Capecitabine plus hepatic intra-arterial epirubicin and cisplatin in unresectable biliary cancer: a phase II study. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(4C):3009–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kemeny NE, Jarnagin WR, Capanu M, Fong Y, Gewirtz AN, Dematteo RP, et al. Randomized phase II trial of adjuvant hepatic arterial infusion and systemic chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with resected hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(7):884–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]