Abstract

Objectives

Delirium is frequently missed in older emergency department (ED) patients. Brief (<2 minutes) delirium assessments have been validated for the ED, but some ED health care providers may consider them to be cumbersome. The Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) is an observational scale that quantifies level of consciousness and takes less than 10 seconds to perform. The authors sought to explore the diagnostic accuracy of the RASS for delirium in older ED patients.

Methods

This was a preplanned analysis of a prospective observational study designed to validate brief delirium assessments for the ED. The study was conducted at an academic ED and enrolled patients who were 65 years or older. Patients who were non-English speaking, deaf, blind, comatose, or had end-stage dementia were excluded. A research assistant (RA) and a physician performed the RASS at the time of enrollment. Within 3 hours, a consultation-liaison psychiatrist performed his or her comprehensive reference standard assessment for delirium using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria. Sensitivities, specificities, and likelihood ratios with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

Results

Of 406 enrolled patients, 50 (12.3%) had delirium diagnosed by the consult-liaison psychiatrist reference rater. When performed by the RA, a RASS other than 0 (RASS > 0 or < 0) was 84.0% sensitive (95% CI = 73.8% to 94.2%), and 87.6% specific (95% CI = 84.2% to 91.1%) for delirium. When performed by physician, a RASS other than 0 was 82.0% sensitive (95% CI = 71.4% to 92.6%) and 85.1% specific (95% CI = 81.4% to 88.8%) for delirium. Using a RASS > +1 or < −1 as the cut-off, the specificity improved to approximately 99% for both raters at the expense of sensitivity; the sensitivities were 22.0% (95% CI = 10.5% to 33.5%) and 16.0% (95% CI = 5.8% to 25.2%) in the RAs and physician raters, respectively. The positive likelihood ratio was 19.6 (95% CI = 6.5 to 59.1) when performed by the RA, and 57.0 (95% CI = 7.3 to 445.9) when performed by the physician, indicating that a RASS > +1 or < −1 strongly increased the likelihood of delirium. The weighted kappa was 0.63, indicating moderate interobserver reliability.

Conclusions

In older ED patients, a RASS other than 0 has very good sensitivity and specificity for delirium as diagnosed by a psychiatrist. A RASS > +1 or < −1 is nearly diagnostic for delirium given the very high positive likelihood ratio.

INTRODUCTION

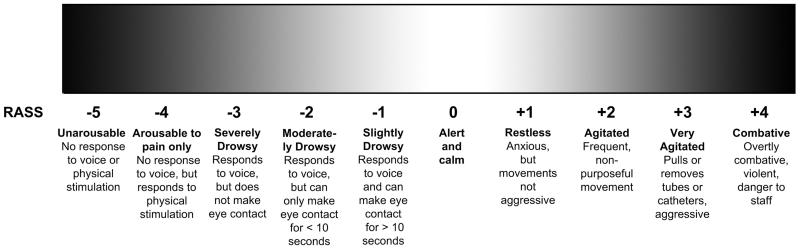

Delirium is a form of acute brain failure that affects 8% to 10% of older emergency department (ED) patients.1,2 Despite being associated with increased mortality3 and accelerated functional and cognitive decline,4,5 emergency health care providers miss delirium in 75% of the cases.1,2 To help improve delirium recognition, the Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM) was developed and validated for older ED patients,6 and has been incorporated into the Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines.7 Although the bCAM takes less than two minutes perform, some ED health care providers may be reluctant to adopt it into their routine clinical practice, seeking even more rapid assessments of acute brain function. The Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS; Figure 1), which quantifies level of consciousness, may be a reasonable alternative to delirium screening in the ED. Altered level of consciousness is often observed in delirium and is key feature in several delirium assessments.6 It takes less than 10 seconds to perform and can be assessed for by simply observing the patient during routine clinical care and does not require additional cognitive testing. Previous studies have evaluated the RASS in hospitalized medical and hip fracture patients, but have limited generalizability to the older ED patient population, who include both admitted and discharged patients.8,9 The purpose of this study was to determine the diagnostic accuracy of the RASS for delirium in older ED patients.

Figure 1.

Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale. Courtesy of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN. Copyright © 2012. Used with Permission.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a preplanned analysis of a prospective observational study designed to validate brief delirium assessments for older ED patients.6 The local institutional review board reviewed and approved this study.

Study Setting and Population

This study was conducted at an academic, tertiary care ED with an annual census of approximately 57,000 visits. A convenience sample of patients was enrolled from July 2009 to February 2012, Monday through Friday between 8 AM and 4 PM. The enrollment window was based on the psychiatrists’ availability. One patient was enrolled per day because the psychiatrists’ comprehensive assessments were conducted in addition to their clinical duties. The first patient who met all the eligibility criteria was enrolled each day. Patients who were 65 years or older, in the ED for less than 12 hours at the time of enrollment, and not in a hallway bed were eligible. The 12 hour cut-off was used to include patients who presented to the ED in the evening and early morning hours. Patients were excluded if they were non-English speaking, deaf or blind, previously enrolled, non-verbal or unable to follow simple commands prior to their acute illnesses, comatose, or did not complete all the study assessments. Patients who were non-verbal or unable to follow simple commands prior to their acute illnesses were considered to have end-stage dementia. These patients were excluded because diagnosing delirium in this patient group can be challenging, even for an experienced psychiatrist.

Study Protocol

The RASS is an arousal scale commonly used in intensive care units to assess for depth of sedation (Figure 1),10 but has been incorporated into several delirium assessments to assess for level of consciousness.6 For this study, we replaced the term “sedation” with “drowsy,” (Figure 1) to describe level of consciousness regardless of sedation administration. A RASS of 0 represented normal level of consciousness whereas a RASS other than 0 represented the presence of altered level of consciousness. The RASS was determined by an emergency physician (EP) and research assistants (RAs; college graduates, emergency medical technicians, and paramedics). Before the study began, the RAs were given a 5-minute didactic lecture about the RASS. The principal investigator then observed them perform the RASS in five older ED patients and provided them instruction if there was any discordance.

The reference standard assessment for delirium was performed by one of three consultation-liaison psychiatrists who diagnose delirium as part of their routine clinical practice. They had an average of 11 years of clinical experience. Their assessment was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision criteria (DSM-IV-TR).11 Details of their assessment have been described in previous reports.6 Briefly, they used all means of patient evaluation and testing, as well as data gathered from those who best understand the patient’s current mental status (e.g., the patient’s surrogates, physicians, and nurses). They performed a battery of cognitive tests, a focused neurological examination, and evaluated each patient for affective lability, hallucinations, and arousal level as part of their evaluations.

Once a patient was enrolled and consented, the RA and EP assessed the patient’s RASS at the same time, but their assessments were blinded to each other. This method of reliability testing was performed to minimize any discrepancies that may have occurred as a result of time, especially since level of consciousness can fluctuate rapidly. The research raters and psychiatrists were also blinded to each other, and all assessments were performed within 3 hours of each other. Medical record review was performed after the patient was enrolled to determine dementia status. Dementia was defined as the presence of this diagnosis in medical record documentation or use of a cholinesterase inhibitor.

Data Analysis

Measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables are reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), respectively. Categorical variables are reported as proportions. Sensitivities, specificities, positive likelihood ratios (+LRs), and negative likelihood ratios (−LRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for both the RA and EP RASS assessments, using the psychiatrist’s DSM-IV-TR assessment as the reference standard for delirium.19 Diagnostic performances were calculated for two cut-points: 1) a RASS other than 0 (RASS > 0 or <0), and 2) a RASS > +1 or < −1, which represented more significant impairment of consciousness. Weighted kappa statistics were also calculated to measure inter-observer reliability between the RA and EP. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

RESULTS

A total of 953 patients were screened, 406 met enrollment criteria (Data Supplement 1), and of these, 50 (12.3%) were diagnosed with delirium by the psychiatrists. Patient characteristics have been previously described in other reports.6 In summary, the median age was 73.5 years old (IQR: 69 to 80 years), 202 (49.8%) were female, 57 (14.0%) were non-white race, and 24 (5.9%) had dementia documented in the medical record. Enrolled and potentially eligible patients were similar in age and sex, but enrolled patients were more likely to be admitted to the hospital, and have a chief complaint of chest pain.6

The diagnostic performance of the RASS by the RAs and EP can be seen in the Table 1. A RASS other than 0 had very good sensitivity and specificity. A RASS of 0 moderately decreased the likelihood of delirium, while a RASS other than 0 moderately increased the likelihood. Using a RASS > +1 or < −1 as the cut-off, the specificity improved to approximately 99% for both raters at the expense of sensitivity (16% to 22.0%) in the RA and physician raters. A RASS > +1 or < −1 strongly increased the likelihood of delirium. The weighted kappa was 0.63 (95% CI = 0.59 to 0.67) indicating moderate interobserver reliability between the RA and EP.

Table 1.

Diagnostic performances of the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS).

| Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | +LR | −LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research assistant | ||||

| RASS other than 0 | 84.0% (73.8-94.2) | 87.6% (84.2-91.1) | 6.8 (5.0–9.2) | 0.2 (0.1 – 0.3) |

| RASS > +1 or < −1 | 22.0% (10.5-33.5) | 98.9% (97.8-100.0) | 19.6 (6.5–59.1) | 0.8 (0.7 – 0.9) |

| Physician | ||||

| RASS other than 0 | 82.0% (71.4-92.6) | 85.1% (81.4-88.8) | 5.5 (4.2–7.3) | 0.2 (0.1 – 0.4) |

| RASS > +1 or < −1 | 16.0% (5.8-25.2) | 99.7% (99.2-100.0) | 57.0 (7.3–445.9) | 0.8 (0.7 – 1.0) |

The reference standard for delirium was a psychiatrist assessment using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria.

DISCUSSION

Delirium is an under-recognized public health problem that is frequently missed by ED health care providers because it is not routinely screened for. The RASS may be a reasonable alternative to screen for delirium in the fast-paced ED environment. Because the RASS can be performed with a brief structured observation, it can be easily incorporated into the routine ED clinical work flow. We observed that a RASS other than 0 had very good sensitivity and specificity and moderately affected the likelihood of delirium. A RASS > +1 or < −1 was nearly diagnostic of delirium as evidenced by its very high specificity and likelihood ratio; no further delirium assessments would be needed in these patients. Despite a brief training period, there was moderately good agreement between the research staff and physician.

Several studies have examined the diagnostic accuracy of altered level of consciousness for delirium. These studies used the modified RASS (mRASS) proposed by the Veteran’s Affairs Delirium Working Group.12 The mRASS is nearly identical to the RASS, except it also incorporates a very informal assessment of inattention. In 95 older medical inpatients, Chester et al. observed that a mRASS other than 0 was 64% sensitive and 93% specific for delirium.8 A mRASS > +1 or < −1 was 34% sensitive and 100% specific for delirium.8 They reported a weighted kappa of 0.48.8 Tieges et al. investigated the mRASS in 30 post-operative hip fracture patients and found a mRASS other than 0 to be 80% sensitive and 90% specific.9 Our findings are remarkably consistent. In 201 older medical inpatients, however, Marcantonio et al. observed that that altered level of consciousness was 19% sensitive for delirium.13 The reasons for this discordance are unclear and may be secondary to differences in case-mix, timing, method of measurement of altered level of consciousness, or method of reference standard assessment.

Several other delirium assessments exist, such as the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), Brief CAM (bCAM), CAM for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU), 3D-CAM, and 4 As test (4AT).6,13-15 However, all these delirium assessments have multiple components and require additional cognitive testing to be performed on the patient. In contrast, the RASS does not require additional testing. As a result, the RASS may be more appealing for some ED providers.

Future research is needed to better define the role of arousal measurement in clinical care. A RASS other than 0 has significant false negatives and false positives rates for delirium, and future research will be needed to determine if a false positive or negative RASS leads to differences in resource utilization and patient outcomes. While an abnormal RASS is an independent predictor of 6-month mortality,16 even in the absence of delirium, its relationship between an abnormal RASS and long-term cognition or function remains unknown and requires further study.

LIMITATIONS

This was a convenience sample, and 38.3% of those approached refused to participate in the study; these two factors likely introduced selection bias. Our enrolled patients were more likely to be admitted and likely had higher severities of illness;6 this may have potentially introduced spectrum bias. Because delirium and the RASS can rapidly fluctuate, and psychoactive medications (e.g. opioid medications) are frequently given in the ED, the allotted 3-hour time interval may have caused some discordant observations between the research team and psychiatrists’ assessments. This can both overestimate and underestimate the RASS’ diagnostic accuracy. We did not test the reliability of the psychiatrist’s DSM-IV-TR assessment. Having a second psychiatrist perform a comprehensive evaluation would have placed undue burden on the patient. To mitigate this issue, we used consultation-liaison psychiatrists who had a wealth of clinical experience in diagnosing delirium to minimize misclassification. We excluded patients with end-stage dementia, defined as not being able to follow simple commands or non-verbal to their acute illness, because diagnosing delirium in these patients is challenging even for a psychiatrist. As result, our findings cannot be generalized to these patients. Finally, the study was performed in at a single, urban, academic hospital, and enrolled patients who were 65 years and older. Our findings may not be generalizable to other settings and those who are under 65 years of age.

CONCLUSIONS

In older emergency department patients, a Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale score other than 0 had very good sensitivity and specificity for delirium as diagnosed by a consultation liaison psychiatrist using DSM-IV-TR criteria. A Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale score > +1 or < −1 is nearly diagnostic of delirium. The Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale may be an alternative method to monitor for delirium when ED health care providers are faced with significant time constraints.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Emergency Medicine Foundation Career Development Award and the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23AG032355. This study was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1 RR024975-01, and is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant 2 UL1 TR000445-06. Dr. Vasilevskis was supported by the National Institutes of Health K23AG040157. Dr. Ely was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health R01AG027472 and R01AG035117, and a Veteran Affairs MERIT award and Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center. Drs. Vasilevskis, Schnelle, Dittus, and Ely are also supported by the Veteran Affairs Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: The American College of Emergency Physicians Research Forum, October 2012, Denver, CO.

Disclosures:

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Emergency Medicine Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hustey FM, Meldon SW, Smith MD, Lex CK. The effect of mental status screening on the care of elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:678–84. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han JH, Shintani A, Eden S, et al. Delirium in the emergency department: an independent predictor of death within 6 months. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:244–52. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inouye SK, Rushing JT, Foreman MD, Palmer RM, Pompei P. Does delirium contribute to poor hospital outcomes? A three-site epidemiologic study. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:234–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross AL, Jones RN, Habtemariam DA, et al. Delirium and long-term cognitive trajectory among persons with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han JH, Wilson A, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Diagnosing delirium in older emergency department patients: validity and reliability of the delirium triage screen and the brief confusion assessment method. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62:457–65. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpenter CR, Bromley M, Caterino JM, et al. Optimal older adult emergency care: Introducing multidisciplinary geriatric emergency department guidelines from the American College of Emergency Physicians, American Geriatrics Society, Emergency Nurses Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63:e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chester JG, Beth Harrington M, Rudolph JL, Group VADW Serial administration of a modified Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale for delirium screening. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:450–3. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tieges Z, McGrath A, Hall RJ, Maclullich AM. Abnormal level of arousal as a predictor of delirium and inattention: an exploratory study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:1244–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1338–44. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association . Task Force on DSM-IV. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flaherty JH, Rudolph J, Shay K, et al. Delirium is a serious and under-recognized problem: why assessment of mental status should be the sixth vital sign. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8:273–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcantonio ER, Ngo LH, O’Connor M, et al. 3D-CAM: derivation and validation of a 3-minute diagnostic interview for CAM-defined delirium: a cross-sectional diagnostic test study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:554–61. doi: 10.7326/M14-0865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han JH, Wilson A, Graves AJ, et al. Validation of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:180–7. doi: 10.1111/acem.12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellelli G, Morandi A, Davis DH, et al. Validation of the 4AT, a new instrument for rapid delirium screening: a study in 234 hospitalised older people. Age Ageing. 2014;43:496–502. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han JH, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani A, et al. Impaired arousal at initial presentation predicts 6-month mortality: an analysis of 1084 acutely ill older patients. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):772–8. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.