Abstract

The objective of this study was to develop and characterize a nanoparticulate-based sustained release formulation of a water soluble dipeptide prodrug of dexamethasone, valine–valine-dexamethasone (VVD). Being hydrophilic in nature, it readily leaches out in the external aqueous medium and hence partitions poorly into the polymeric matrix resulting in minimal entrapment in nanoparticles. Hence, hydrophobic ion pairing (HIP) complexation of the prodrug was employed with dextran sulphate as a complexing polymer. A novel, solid in oil in water emulsion method was employed to encapsulate the prodrug in HIP complex form in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) matrix. Nanoparticles were characterized with respect to size, zeta potential, crystallinity of entrapped drug and surface morphology. A significant enhancement in the entrapment of the prodrug in nanoparticles was achieved. Finally, a simple yet novel method was developed which can also be applicable to encapsulate other charged hydrophilic molecules, such as peptides and proteins.

Keywords: Prodrug, valine–valine-dexamethasone, dextran sulphate, HIP complex, polymeric nanoparticles, characterization of nanoparticles

Introduction

A wide variety of compounds with significantly diverse physicochemical properties have been developed in the past decade due to the adaptation of combinatorial chemistry and high-throughput screening-based approaches. Formulation development of such diverse set of compounds has become a very significant challenge. Colloidal dosage forms have been introduced and widely investigated as drug delivery carriers for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules. Nanoparticulate-based formulation approach has been very successful for the delivery of small and large molecules including in the treatment of ocular diseases (Gaudana et al., 2009, 2010). So far the success of this approach has been limited to hydrophobic drug molecules. This is mostly because of higher entrapment efficiency and ease of formulation with conventional oil in water (O/W) and water in oil in water (W/O/W) emulsion methods. However, these methods failed to provide similar entrapment efficiency in the case of hydrophilic drug molecules because of rapid leaching of these molecules into the external aqueous medium (Bala et al., 2004; Tewes et al., 2007; Cohen-Sela et al., 2009).

Hydrophobic ion pairing (HIP) complexation method is a useful technique for the delivery of protein and peptide molecules (Meyer and Manning, 1998; Dai and Dong, 2007; Yuan et al., 2009). In this approach, an ionizable functional group of the hydrophilic drug molecule is stoichiometrically complexed with an oppositely charged group of a surfactant or polymer to form drug-surfactant or drug-polymer complex, respectively. Depending on the nature of the surfactant or polymer, HIP complex of the drug molecule exhibits significantly higher solubility in organic solvents along with dramatic reduction in its aqueous solubility (Meyer and Manning, 1998). Since the drug molecule exists as a hydrophobic moiety in the HIP complex, during nanoparticle preparation, it would preferentially partition into the hydrophobic polymeric matrix rather than the external aqueous medium. HIP complexation approach may provide many valuable benefits, such as higher drug entrapment, enhanced transport across the biological membrane, sustained release and better enzymatic protection of the complexed drug (Meyer and Manning, 1998; Feng et al., 2004). Most importantly, since a drug molecule is only ionically complexed, it can rapidly dissociate in the presence of oppositely charged ions (Yoo et al., 2001). Thus, this technique obviates the necessity of a chemical conjugation of a drug molecule, which is tedious and often results in the loss of bioactivity especially in the case of peptide and protein-based therapeutics. HIP complexation of small molecules as well as peptide and protein-based therapeutics has already been investigated for molecules, such as leuprolide, melittin and insulin (Yang et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2010).

Dexamethasone is indicated for the treatment of posterior segment eye diseases, such as macular edema, posterior uveitis and proliferative vitreoretinopathy. However, its delivery for the treatment of posterior segment eye diseases is a challenge because of poor aqueous solubility, susceptibility to efflux by P-gp and presence of the blood-retinal barrier (Boddu et al., 2010). Therefore, we have designed dipeptide prodrugs (PD) of dexamethasone, such as valine–valine-dexamethasone (VVD) and glycine–valine-dexamethasone (GVD) to overcome these limitations. These PD molecules can be targeted to the peptide transporters present on the basolateral side of the retina (Kansara et al., 2007). The details about development of peptide conjugates of dexamethasone, their physicochemical characterization, interaction with peptide transporters and transport studies (across sclera and retina-choroid-sclera) are beyond the scope of this article. Our long-term goal is to administer a nanoparticulate-based formulation in the periocular space of the eye to sustain the release of VVD. Numerous studies have confirmed rapid endocytosis of nanoparticles by retinal cells (Del Pozo-Rodriguez et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2009). Aqueous solubility of VVD was about 50 times higher (7 mg/mL) than the parent drug dexamethasone (0.14 mg/mL). Higher solubility of VVD could be attributed to the presence of a terminal amino group and its amorphous nature. Initially, single and double emulsion methods were employed to prepare nanoparticles with poly (DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA 85: 15) as a polymer. Both methods resulted in nanoparticles with less than 10% entrapment of VVD (unpublished data).

Therefore in this article, a novel HIP complex of hydrophilic, water soluble peptide PD (VVD) with dextran sulphate has been reported. VVD has one free terminal cationic amino group available which can undergo ionic complexation with anionic sulphate group of dextran sulphate. Dalwadi and Sunderland have recently selected dextran sulphate as a complexing agent to enhance loading of hydrophilic and lipophilic drug molecules into pegylated PLGA nanoparticles (Dalwadi and Sunderland, 2009). In the present study, we have prepared and optimized HIP complexation of VVD with dextran sulphate. We also studied the dissociation phenomenon of VVD from HIP complex to understand the nature of interaction. Further, we investigated the effect of molar ratio of dextran sulphate to VVD and pH of aqueous medium of VVD on the complexation between VVD and dextran sulphate. The hydrophobic complex was not only insoluble in aqueous media but also found to be insoluble in organic solvents, such as methylene chloride and acetonitrile. Hence, formulation using the single emulsion (O/W) method was not feasible. Therefore, we employed the solid in oil in water (S/O/W) emulsion approach for nanoparticles preparation using VVD in HIP complex form and evaluated formulation parameters. Later, nanoparticles were characterized for particle size, zeta potential, X-ray diffraction (XRD), surface morphology (using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM)), entrapment efficiency and drug release profile.

Materials and methods

Materials

Dexamethasone was obtained from Biomol. Boc-valine– valine was obtained from CPC scientific. 1-[3-dimethyla-minopropyl]-3-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC) was obtained from Acros organics. 4-Dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), dextran sulphate sodium salt (molecular weight of 9000–20 000 Da), poly (DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA 85:15, molecular weight of 50 000–75 000 Da), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulphate (TBAHS) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. All solvents and other reagents of analytical grade were purchased from a local supplier and used as such without any purification. Distilled deionized water (DDW) was used throughout the study.

Synthesis of VVD

The synthesis scheme to conjugate dipeptide moiety to various drug molecules has been previously published from our laboratory (Agarwal et al., 2008; Talluri et al., 2008). Briefly, commercially available Boc-valine– valine-OH and EDC were taken in reaction flask-1 (mole ratio 1:1). Flask content was dissolved in dry DMF and stirred for 1 h. In a separate reaction flask-2, dexamethasone and DMAP (mole ratio 1:1.5) were dissolved in DMF and stirred for 10 min at room temperature under inert atmosphere. Content of flask-2 was added into flask-1 through a syringe in drop-wise manner and allowed to come to the room temperature and stirred for 48 h. Small portion of the reaction mixture was taken out and injected in LC/MS to ensure the complete conversion of the starting material to product. The reaction mixture was filtered and filtrate was evaporated at room temperature under reduced pressure to get crude product Boc-VVD. The product was purified by silica column chromatography using 5% CH3OH/CH2Cl2 as eluent. N-Boc-VVD was treated with 80% TFA/CH2Cl2 at 0°C for 2.5 h to remove protecting group. Reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by cold diethyl ether precipitation to get the final product VVD as a TFA salt. The prodrug was allowed to dry under vacuum before using it for the biological evaluation. Figure 1 contains the details of synthesis scheme of VVD. An HPLC method was developed for simultaneous analysis of VVD and dexamethasone. Waters 515 pump (Waters, Milford, MA) equipped with a UV detector (RAININ, Dynamax, Absorbance Detector Model UV-C) was employed for the HPLC analysis. A C18 column was used as a stationary phase and water: acetonitrile (65:35; v/v) was selected as the mobile phase. VVD and dexamethasone were detected at 254 nm at the flow rate of 1 mL/min. We employed TBAHS dissolved in aqueous phase (10 mM) as an ion pairing agent. The characteristic HPLC peaks of VVD (as a doublet) and dexamethasone are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Synthesis scheme of VVD.

Figure 2.

Representative HPLC chromatogram of VVD (10 ug/mL) and dexamethasone (2 ug/mL). The retention time of VVD was 6.3 and 6.5 min while the retention time of dexamethasone was 8.2 min.

General preparation method of HIP complex between VVD and dextran sulphate

Formation of HIP complex between VVD and dextran sulphate was a single step process. Briefly, aqueous solutions of VVD and dextran sulphate were prepared separately with DDW. To form the HIP complex, aqueous solution of dextran sulphate was added to the aqueous solution of VVD. Once both the aqueous solutions were mixed and vortexed, HIP complex formed instantaneously. The complex was separated by centrifugation at 10 000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was isolated and analysed to measure the uncomplexed free VVD by HPLC. Percentage complexed VVD was calculated with the following Equation (1).

| (1) |

Effect of molar ratios of dextran sulphate to VVD on complex formation

HIP complexes were prepared by varying molar ratios of dextran sulphate to VVD. An aqueous solution of dextran sulphate was added to VVD solution in different ratios to form the HIP complex. Various molar ratios of dextran sulphate/VVD were studied, such as 0.003, 0.007, 0.014, 0.029 and 0.058. These solutions were centrifuged to obtain a clear supernatant followed by HPLC analysis to measure uncomplexed VVD.

Effect of pH of aqueous solution of VVD on HIP complex formation

An aqueous solution of VVD was prepared and the pH was adjusted to 4.5, 5.5, 6.5, 7.5 and 8.5 using 0.1 M NaOH. Dextran sulphate solution was added to the VVD solution to form the HIP complex (molar ratio of dextran sulphate/ VVD 0.014). Uncomplexed VVD was measured in the supernatant using the above mentioned process.

Dissociation of the HIP complex

Dissociation of the HIP complex was also studied to understand the nature of interaction between dextran sulphate and VVD. For this study, initially the HIP complex of dextran sulphate and VVD was prepared in the molar ratio of 0.014. The HIP complex was separated from uncomplexed prodrug by centrifugation. Later, the complex was redispersed with DPBS solution having different concentrations of NaCl (10 mM and 100 mM) and DDW. These solutions were kept for equilibration for a period of 2h at 37°C using a rotor. Following equilibration, the HIP complex and VVD were separated by centrifugation and uncomplexed VVD was measured by analysing the supernatant.

Preparation of nanoparticles by solid/oil/water (S/O/W) emulsion method

Five milligram of VVD in the form of HIP complex was used for the preparation of nanoparticles. Three millilitres of methylene chloride was gradually added to the complex and the mixture was vortexed for 2–3 min. Various ratios of VVD:PLGA 85:15 were employed to prepare the nanoparticles, such as 1:10, 1:15 and 1:20. PLGA 85:15 was dissolved separately in 4 mL of methylene chloride. This solution was gradually added to the earlier prepared dispersion containing HIP complex. Parameters such as total volume of methylene chloride and vortexing time were optimized to obtain an S/O dispersion. About 7 mL of methylene chloride was required to completely disperse the HIP complex. Later, sonication was performed for about 2–3 min using tip sonicator (Fisher 100 Sonic dismembrator, Fisher Scientific) at a constant power output of 25 W to obtain the fine S/O dispersion. To this S/O dispersion stored in ice, external aqueous phase (30 mL, 1% PVA) was added followed by further sonication for 3 min under similar conditions. This procedure resulted in S/O/W nanoemulsion. The nanoemulsion was kept on a shaker bath at room temperature for 15–20 min followed by complete evaporation of methylene chloride under Rotavap for about 2 h. Later, this nanodispersion was centrifuged for 50 min at 22 000×g. Nanoparticles formed were washed two times with DI water to remove surface bound VVD and PVA followed by freeze drying.

Characterization of nanoparticles

Entrapment efficiency of nanoparticles

An aliquot (0.5 mL) of freshly prepared nanosuspension was dissolved in 10 mL of DMSO: ACN (20/80; v/v). Later, this solution was thoroughly mixed for 4 h and sonicated in a bath sonicator to obtain a clear solution. The solution was subjected to centrifugation for 10 min and the supernatant was collected and subsequently analysed by HPLC to estimate VVD entrapment in nanoparticles.

Particle size and zeta potential measurement

The mean particle size and polydispersity of the nanoparticles were measured at 25°C by DLS (Brookhaven Inst. Co., Holtsville, NY) at an operating angle of 90°. A dilute sample of the nanosuspension (1:5) in DI water was employed for particle size analysis. At least triplicate measurements of each batch was carried out. For zeta potential measurement, freeze dried nanoparticles were suspended in DI water and then surface charge of nanoparticles was measured with the Malvern Zetasizer apparatus (Malvern Instruments Ltd, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK).

X-ray diffraction

XRD patterns in this study were obtained by a Rigaku MiniFlex automated diffractometer using Cu-Kα radiation (1.5405 Å) with a NiKb filter. The tube was operated at 30 kV, 15 mA and the scan range was 10–50° 2θ at 0.5°/min. Aliquots of sample (7.1 mg) were dispersed in benzene on a zero-background silicon plate, air-dried and scanned.

Scanning electron microscopy

SEM images were obtained to study the morphology of nanoparticles. A drop of nanosuspension was placed on a nucleopore filter in a hand-pumped vacuum chamber with a permeable membrane supporting the filter. Vacuum was applied to enhance filtration rate. The filters were mounted on SEM stubs with double-sticky carbon tabs and then the edges were coated with colloidal silver for conductivity. The samples were then sputter-coated with platinum for 1 min at 20 mA current. Images were taken on a Hitachi S4700 field-emission SEM at accelerating voltages of 5 and 10 kV.

Transmission electron microscopy

The surface morphology and appearance of nanoparticles were further studied with TEM. Briefly, freeze dried sample of nanoparticles was placed on 200-mesh copper carbon-coated grids and stained with 1.3% phosphotungstic acid. Images were captured on a JEOL JEM 1400 transmission electron microscope with a 2 k × 2 k Gatan digital camera.

Release of VVD from nanoparticles

For release study, 1.5 mL of the nanoparticle suspension was added into dialysis bags (MWCO: 10 000). The dialysis bags were carefully placed into glass tubes containing 9mL of PBS buffer and DDW. These tubes were stirred at 60rpm at 37°C. Samples were taken at predetermined time points and the entire release medium was replaced by either fresh PBS buffer or DDW. VVD release from nanoparticles was analysed with HPLC.

Results and discussion

The main objective of this study was to formulate and characterize a nanoparticulate formulation of a hydrophilic water soluble prodrug of dexamethasone. We have synthesized, characterized and established a HPLC method to analyse VVD and dexamethasone in our laboratory (Figure 2). The objective of synthesizing dipeptide prodrug of dexamethasone was to target peptide transporters present on basolateral surface of RPE following subconjunctival injection. Aqueous solubility of VVD was found to be almost 50-fold higher than the parent drug. This solubility enhancement was very crucial to overcome several limitations associated with the current delivery of dexamethasone. However, at the same time, development of a nanoparticulate formulation with higher loading efficiency became a challenging task. Conventional methods of nanoparticles preparation, such as O/W and W/O/W emulsion have failed to provide higher entrapment efficiency of VVD (entrapment less than 10%) (unpublished data). Higher affinity of VVD for the external aqueous phase was the primary reason for its lower entrapment when the conventional methods of preparation were employed. Due to higher aqueous solubility, VVD molecules diffuse readily into the external aqueous phase resulting in lower partitioning into the hydrophobic polymeric matrices. Several investigators have chemically modified the hydrophilic drug molecules to hydrophobic molecules to enhance its partitioning into nanoparticles. However, it is a tedious and cumbersome process. Moreover, these modifications might result in the loss of bioactivity of the parent molecule. Hence, there is a strong need to design an alternative strategy to convert these water soluble compounds into water insoluble hydrophobic moieties because these water insoluble compounds can be easily encapsulated in polymeric nanoparticles.

Structures of VVD and dextran sulphate are shown in Figure 3. We used dextran sulphate as a complexing agent for VVD. Dextran is a polymer of anhydroglucose and it has been widely employed as a potential adjuvant in various pharmaceutical formulations (Chen et al., 2008a, b; Halfter, 2008; Dalwadi and Sunderland, 2009; Woitiski et al., 2009; Tan et al., 2010). Dextran sulphate contains 2.3 sulphate groups per glucosyl residue (Chen et al., 2008a, b). In this study, terminal amino group of VVD was complexed with the sulphate group of dextran sulphate to form water insoluble HIP complex. HIP complex of VVD was hydrophobic in nature and its solubility was dramatically reduced in water and organic solvents, such as methylene chloride and acetonitrile. This complex form of VVD was encapsulated to prepare a nanoparticulate-based formulation. Therefore, in this study, the S/O/W emulsion method was employed to formulate nanoparticles.

Figure 3.

Structures of (a) VVD and (b) dextran sulphate.

HIP complex formation was studied at different molar ratios of dextran sulphate to VVD, such as 0.003, 0.007, 0.014, 0.029 and 0.058. These molar ratios represent different amounts of dextran sulphate added to the VVD solution to form the HIP complex. A stoichiometric relationship between the amounts of dextran sulphate added and the formation of HIP complex was obtained (Figure 4). This result was consistent with previously published studies of HIP complexes of leuprolide, insulin, melittin which were prepared using surfactants (Yoo et al., 2001; Yuan et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2010). When the molar ratio of dextran sulphate to VVD was 0.014, more than 99% of VVD molecules were found in the HIP complex form (Figure 4). Theoretically, at this molar ratio, negatively charged species (sulphate groups of dextran sulphate) and positively charged species (amino groups of VVD) were at equal concentration in the solution. Almost all VVD molecules were ionically complexed with dextran sulphate. When the molar ratio was less than 0.014, sulphate groups present in the aqueous solution were not sufficient to completely bind to all the available amino groups of VVD. Therefore, after HIP complex formation, uncomplexed VVD was also observed in the supernatant. When the molar ratios of dextran sulphate to VVD were 0.003 and 0.007, 45% and 70% of VVD molecules were available in the HIP complex form. Theoretically, at these molar ratios, the sulphate groups present in the solution were sufficient to complex only 25% and 50% of the amino groups of VVD molecules. Still, almost 45% and 70% of VVD molecules were complexed with dextran sulphate (Figure 4). Therefore, two different mechanisms may be responsible for HIP complex formation (1) ion pairing and (2) hydrophobic interactions. After mixing aqueous solutions of dextran sulphate and VVD, apart from ion pairing, hydrophobic interactions can rightfully contribute to complex formation. Due to hydrophobic interactions, even at lower molar ratios (0.003 and 0.007), significant binding of dextran sulphate with VVD was observed as reported by several investigators who have employed different drug molecule and complexing agent to prepare HIP complex (Yoo et al., 2001). Binding efficiency was more than 99% at any molar ratio higher than 0.014. Moreover, an excess addition of dextran sulphate did not result in any significant change in the HIP complexation with VVD. This was quite surprising. It is probable that mechanism of HIP complex formation using dextran sulphate differs than that of HIP complex formation with any surfactant. In the later mechanism, excessive addition of surfactant beyond its critical micelle formation concentration (CMC) will cause formation of micelles. Due to micellization, reversion of HIP complexation occurs and thus, solute molecules solubilize again (Yang et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2009). Interestingly, in the case of dextran sulphate, similar behaviour even at higher molar ratio of dextran sulphate to VVD (any molar ratio greater than 0.014) was not observed. This may be because of predominance of non-specific hydrophobic interactions between dextran sulphate and VVD, which prevented the formation of micelles. Further studies are in progress to investigate this mechanism where we have employed small molecular weight of dextran sulphate and anionic surfactants to form HIP complex.

Figure 4.

Effect of different molar ratio of dextran sulphate/VVD on HIP complexation. Values are given as mean ± SD (n = 3).

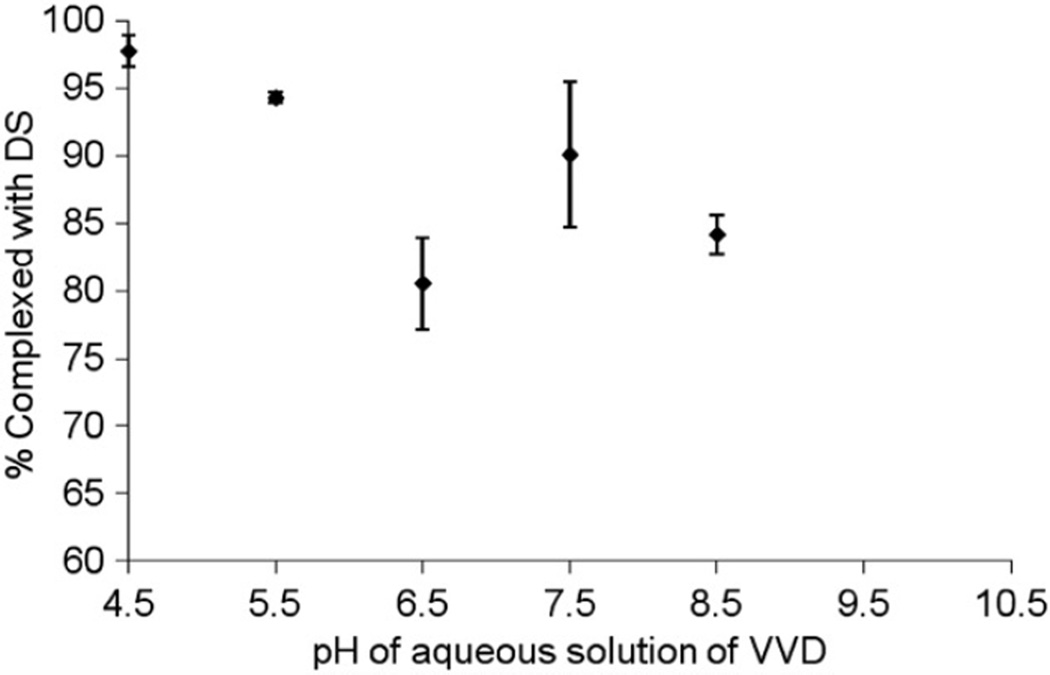

The effect of pH on complexation of VVD with dextran sulphate was also studied. Previously, we have investigated the buffer stability of the VVD at different pH values (data not included). Our results suggested that stability of VVD was higher at lower pH and as pH was increased, the stability of prodrug was found to be decreased. This stability data was also consistent with the previously published results from our laboratory (Majumdar et al., 2005). The result of this experiment further explains the role of hydrophobic interactions. Amino group of VVD has pKa value close to ≈10. Thus, at pH 4.5, 5.5, 6.5, 7.5 and 8.5, amino group would have net positive charge and hence can bind with sulphate group of dextran sulphate. As pH of aqueous solution of VVD approaches towards its pKa (from pH 4.5 to pH 8.5), less amino group of VVD would carry cationic property. Hence, less molecules of VVD will ionically bind with dextran sulphate and more VVD molecules will remain in the supernatant. However, more than 80% of VVD molecules were found in the form of HIP complex at pH 6.5, 7.5 and 8.5 (Figure 5). A steep decline in the percentage binding of VVD molecules with dextran sulphate was not observed. This phenomenon can be attributed to the hydrophobic interactions. As the pH of the VVD solution approached its pKa, hydrophobic interactions became more predominant than the ionic interactions. Similar behaviour was also reported by other investigators in the past (Yoo et al., 2001).

Figure 5.

Effect of pH of aqueous solution of VVD on HIP complex formation with dextran sulphate. Values are given as mean ± SD (n = 3).

The dissociation of VVD from HIP complex was also studied. Since interaction between dextran sulphate and VVD was mainly driven by non-covalent forces, such as ionic and hydrophobic interactions, dissociation of VVD from HIP complex in the presence of negatively charged species was probable. HIP complex (prepared at molar ratio of dextran sulphate/VVD, 0.014) was re-dispersed in DPBS with varying concentrations of NaCl (10 and 100 mM) and DDW. Analysis of supernatant revealed that almost 5% and 15% VVD dissociated from the HIP complex which were redispersed with DPBS buffer having 10 and 100 mM of NaCl, respectively (Figure 6). Interestingly, we did not observe significant dissociation of VVD from HIP complex which was redispersed with DDW (Figure 6). This might be because of the absence of negatively charged species, such as chloride ions in DDW, and thus VVD did not dissociate from the HIP complex. Slow dissociation of VVD from the HIP complex can be beneficial in several ways. Due to slow dissociation, release of VVD can be sustained at the target site. Therefore, selection of the complexing agent is very important in the HIP complexation process. Dissociation and release parameters of a drug molecule may vary depending upon the nature of the complexing agent.

Figure 6.

Effect of dispersing medium on dissociation of VVD from HIP complex. Values are given as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Nanoparticles were prepared with the S/O/W emulsion method. Recently, this method was investigated for the preparation of nanoparticles for a variety of drug molecules (Bilati et al., 2005; Kumar et al., 2006). Methylene chloride was selected as a common solvent to dissolve PLGA 85:15 and disperse HIP complex. Critical parameters affecting nanoparticle formulation were total volume of methylene chloride used, total duration of vortex processing and the duration of sonication. A fine dispersion of solid (HIP complex of VVD with dextran sulphate) in oil (methylene chloride) was necessary to prepare final S/O/ W emulsion. Addition of PLGA aided in rapid dispersion of HIP complex in methylene chloride. As the amount of PLGA 85:15 increased, the dispersion process of HIP complex in methylene chloride became rapid. Sonication was carried out to achieve a fine dispersion of solid (HIP complex) in oil (methylene chloride). To this S/O dispersion, 30 mL of 1% PVA solution was added followed by sonication in ice bath to obtain S/O/W nanoemulsion. Temperature was controlled during the sonication process using ice bath to ensure stability of the VVD. Later, methylene chloride was evaporated with a rotovap and nanoparticles were freeze dried and stored at −80°C.

Prepared nanoparticles were characterized with respect to size, zeta potential and surface morphology. Size and shape of the colloidal dosage forms dramatically affect their in vivo performance. The size of the nanoparticles was found to be less than 200 nm in all cases. Low polydispersity values indicate uniformity in the particle size and the narrow particle size distribution for various batches of nanoparticles. Based on the results of this study, we hypothesized rapid endocytosis and translocation of these nanoparticles in the retinal cells. Previous studies from other labs have also shown endocytosis of nanoparticles by retinal cells (Del Pozo-Rodriguez et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2009). Our result also shows feasibility of preparing nanoparticles with uniform size and narrow particle size distribution using the S/O/W emulsion method. For all batches of nanoparticles, zeta potential values were negative (Table 1). This could be due to negative surface charges of PLGA and dextran sulphate. These results are consistent with previously published studies which have shown the presence of a negative surface charge on the nanoparticles (Perez et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2008a, b).

Table 1.

Zeta potential, particle size, polydispersity and entrapment efficiency of various batches of nanoparticles. Values are given as mean ± SD (n = 3).

| Ratio of PD to polymer |

Zeta potential (mV) |

Particle size (nm) |

Polydispersity | % Entrapment efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:10 | −12.3 ± 0.95 | 139.5 ± 5.84 nm | 0.005 | 25.3 ± 4.9 |

| 1:15 | −6.41 ± 0.62 | 157.7 ± 5.08 nm | 0.005 | 34.25 ± 1.3 |

| 1:20 | −11.4 ± 1.09 | 124.2 ± 1.47 nm | 0.005 | 45.7 ± 1.43 |

Surface morphology of nanoparticles was characterized with SEM and TEM (Figures 7 and 8). These studies revealed that particles were uniform in appearance and round in shape. This result further confirmed particle size analysis data by DLS. Nanoparticles appeared uniformly and did not exhibit significant aggregation.

Figure 7.

SEM images of nanoparticles prepared with different ratios of HIP complex: PLGA (a) 1:10, (b) 1:15 and (c) 1:20.

Figure 8.

TEM images of nanoparticles prepared with different ratios of HIP complex: PLGA (a) 1:10, (b) 1:15 and (c) 1:20.

An important objective of this study was to achieve higher entrapment efficiency of VVD in polymeric nanoparticles. PLGA 85:15 was selected in the current study due to its higher lactide content. As the lactide content increases, hydrophobic interactions with HIP complex would increase as well. This might result in higher partition of HIP complex in polymeric matrix of PLGA. Results clearly show that when higher amounts of PLGA 85:15 were added for the nanoparticle preparation, entrapment of VVD in nanoparticles increased simultaneously. Among the three different ratios of VVD in HIP complex form: PLGA studied, the least entrapment (≈25%) was observed when the ratio was 1:10. Maximum entrapment of VVD (≈45%) was obtained when the ratio reached 1:20 (Table 1). A dramatic enhancement in the entrapment efficiency was noticed with the HIP complex technique relative to conventional methods of preparation, such as single and double emulsion. This study also shows that other than protein-based therapeutics, HIP complexation can also be a useful tool to enhance the loading of small hydrophilic, water soluble molecules in nanoparticles. This technique would provide the flexibility to alter the aqueous solubility of a compound in a reversible manner. Therefore, it may serve as a viable alternative to covalent modification of drug molecules. Selection of complexing agent is very crucial because physicochemical properties of HIP complex may vary depending on the nature of the complexing agent.

VVD was amorphous in nature which was also one of the reasons for its higher aqueous solubility. Therefore, XRD studies were carried out to understand if the VVD still remained in the amorphous form within the core of nanoparticles. XRD diffractogram showed lack of crystalline nature for VVD, dextran sulphate, HIP complex and PLGA (Figure 9). XRD diffractogram of the freeze dried nanoparticles of different batches is also shown in the same figure, which confirms that VVD exists in the amorphous form within PLGA matrix.

Figure 9.

X-ray diffractogram of (a) dextran sulphate, (b) VVD, (c) HIP complex, (d) PLGA and different batches of nanoparticles (e) 1:10, (f) 1:15 and (g) 1:20.

Finally, the release of VVD from nanoparticles was compared in two different releasing media. PBS buffer and DDW were selected as release medium. Based on previous results of dissociation of VVD from HIP complex, it is likely that slower release of VVD from the nanoparticles will occur in the presence of DDW relative to PBS buffer. Our results show dramatic difference in the release of VVD in two different media. In the case of PBS buffer, significant burst effect was observed which resulted in release of ≈80% of VVD in 24 h. This could be due to rapid dissociation of VVD from HIP complex which was absorbed on surface and also entrapped within polymeric matrix. The burst release phenomenon from PLGA nanoparticles has been widely reported in the literature (Li et al., 2001; Kim and Martin, 2006). However, in the case of DDW, burst effect was significantly attenuated (Figure 10). This may be due to the absence of negatively charged ions in DDW which resulted in the slow dissociation of VVD from HIP complex. Moreover, due to higher molecular weight of HIP complex, its diffusion from polymeric matrix would be slower compared to free VVD. Overall release was also comparatively slower when DDW was chosen as the releasing medium. Release of VVD was sustained for 14 days in DDW compared to 5 days where PBS served as the medium (Figure 10). Release data also suggests that nanoparticles may sustain the release of VVD at the targeted site. Further studies are in progress to evaluate in vivo performance of a novel sustained release VVD nanoparticulate formulation in the rabbit animal model.

Figure 10.

Comparison of release of the VVD from nanoparticles in different releasing media. Values are given as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Conclusions

The objective of this study was to design and characterize a nanoparticulate-based sustained release formulation of a water soluble prodrug of dexamethasone. An HIP complexation method with dextran sulphate as a complexing agent was utilized to convert hydrophilic prodrug (VVD) into a hydrophobic complex. Various parameters of HIP complexation were studied and optimized. HIP complex of VVD was encapsulated in nanoparticles by the S/O/W emulsion method. Prepared nanoparticles were characterized with respect to size, zeta potential and surface morphology (using SEM and TEM). Entrapment efficiency of prodrug was dramatically enhanced compared to conventional techniques, such as single and double emulsion methods. XRD studies revealed the amorphous nature of the prodrug within nanoparticles. A significant difference in the release profile of VVD was observed from nanoparticles when we employed PBS buffer and DDW as releasing medium. Finally, a simple yet novel method was developed to encapsulate water soluble hydrophilic molecules in polymeric nanoparticles. This method may also be applicable to other small hydrophilic and peptide/protein-based molecules.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Dr Elisabet Kostoryz, School of Dentistry and James Murowchick, Department of Geological Science, for assisting us in dynamic light scattering and XRD studies.

Declaration of interest

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 EY 09171-14 and R01 EY 10659-12.

References

- Agarwal S, Boddu SH, Jain R, Samanta S, Pal D, Mitra AK. Peptide prodrugs: Improved oral absorption of lopinavir, a HIV protease inhibitor. Int J Pharm. 2008;359:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bala I, Hariharan S, Kumar MN. PLGA nanoparticles in drug delivery: The state of the art. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2004;21:387–422. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v21.i5.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilati U, Allemann E, Doelker E. Nanoprecipitation versus emulsion-based techniques for the encapsulation of proteins into biodegradable nano-particles and process-related stability issues. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2005;6:E594–E604. doi: 10.1208/pt060474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddu SH, Jwala J, Vaishya R, Earla R, Karla PK, Pal D, Mitra AK. Novel nanoparticulate gel formulations of steroids for the treatment of macular edema. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2010;26:37–48. doi: 10.1089/jop.2009.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Siddalingappa B, Chan PH, Benson HA. Development of a chitosan-based nanoparticle formulation for delivery of a hydrophilic hexapeptide, dalargin. Biopolymers. 2008a;90:663–670. doi: 10.1002/bip.21055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Wang F, Benson HA. Effect of formulation factors on incorporation of the hydrophilic peptide dalargin into PLGA and mPEG-PLGA nanoparticles. Biopolymers. 2008b;90:644–650. doi: 10.1002/bip.21013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Sela E, Chorny M, Koroukhov N, Danenberg HD, Golomb G. A new double emulsion solvent diffusion technique for encapsulating hydrophilic molecules in PLGA nanoparticles. J Controlled Release. 2009;133:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai WG, Dong LC. Characterization of physiochemical and biological properties of an insulin/lauryl sulfate complex formed by hydrophobic ion pairing. Int J Pharm. 2007;336:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalwadi G, Sunderland B. An ion pairing approach to increase the loading of hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs into PEGylated PLGA nanoparticles. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;71:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo-Rodriguez A, Delgado D, Solinis MA, Gascon AR, Pedraz JL. Solid lipid nanoparticles for retinal gene therapy: Transfection and intracellular trafficking in RPE cells. Int J Pharm. 2008;360:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, De Dille A, Jameson VJ, Smith L, Dernell WS, Manning MC. Improved potency of cisplatin by hydrophobic ion pairing. Canc Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;54:441–448. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0840-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudana R, Ananthula HK, Parenky A, Mitra AK. Ocular drug delivery. AAPS J. 2010;12:348–360. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9183-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudana R, Jwala J, Boddu SH, Mitra AK. Recent perspectives in ocular drug delivery. Pharm Res. 2009;26:1197–1216. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9694-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfter W. Change in embryonic eye size and retinal cell proliferation following intravitreal injection of glycosaminoglycans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:3289–3298. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansara V, Hao Y, Mitra AK. Dipeptide monoester ganciclovir prodrugs for transscleral drug delivery: Targeting the oligopeptide transporter on rabbit retina. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23:321–334. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Martin DC. Sustained release of dexamethasone from hydrophilic matrices using PLGA nanoparticles for neural drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3031–3037. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar PS, Ramakrishna S, Saini TR, Diwan PV. Influence of microencap-sulation method and peptide loading on formulation of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) insulin nanoparticles. Pharmazie. 2006;61:613–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Pei Y, Zhang X, Gu Z, Zhou Z, Yuan W, Zhou J, Zhu J, Gao X. PEGylated PLGA nanoparticles as protein carriers: Synthesis, preparation and biodistribution in rats. J Controlled Release. 2001;71:203–211. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar S, Nashed YE, Patel K, Jain R, Itahashi M, Neumann DM, Hill JM, Mitra AK. Dipeptide monoester ganciclovir prodrugs for treating HSV-1-induced corneal epithelial and stromal keratitis: In vitro and in vivo evaluations. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:463–474. doi: 10.1089/jop.2005.21.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JD, Manning MC. Hydrophobic ion pairing: Altering the solubility properties of biomolecules. Pharm Res. 1998;15:188–193. doi: 10.1023/a:1011998014474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez C, Sanchez A, Putnam D, Ting D, Langer R, Alonso MJ. Poly(lactic acid)-poly(ethylene glycol) nanoparticles as new carriers for the delivery of plasmid DNA. J Controlled Release. 2001;75:211–224. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00397-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SR, Grossniklaus HE, Kang SJ, Edelhauser HF, Ambati BK, Kompella UB. Intravenous transferrin, RGD peptide and dual-targeted nanoparticles enhance anti-VEGF intraceptor gene delivery to laser-induced CNV. Gene Ther. 2009;16:645–659. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Liang N, Piao H, Yamamoto H, Kawashima Y, Cui F. Insulin-S.O (sodium oleate) complex-loaded PLGA nanoparticles: Formulation, characterization and in vivo evaluation. J Microencapsul. 2010;27:471–478. doi: 10.3109/02652040903515490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talluri RS, Samanta SK, Gaudana R, Mitra AK. Synthesis, metabolism and cellular permeability of enzymatically stable dipeptide prodrugs of acyclovir. Int J Pharm. 2008;361:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan ML, Friedhuber AM, Dunstan DE, Choong PF, Dass CR. The performance of doxorubicin encapsulated in chitosan-dextran sulphate microparticles in an osteosarcoma model. Biomaterials. 2010;31:541–551. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewes F, Munnier E, Antoon B, Ngaboni Okassa L, Cohen-Jonathan S, Marchais H, Douziech-Eyrolles L, Souce M, Dubois P, Chourpa I. Comparative study of doxorubicin-loaded poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles prepared by single and double emulsion methods. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;66:488–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woitiski CB, Veiga F, Ribeiro A, Neufeld R. Design for optimization of nanoparticles integrating biomaterials for orally dosed insulin. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;73:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Cui F, Shi K, Cun D, Wang R. Design of high payload PLGA nanoparticles containing melittin/sodium dodecyl sulfate complex by the hydrophobic ion-pairing technique. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2009;35:959–968. doi: 10.1080/03639040902718039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HS, Choi HK, Park TG. Protein-fatty acid complex for enhanced loading and stability within biodegradable nanoparticles. J Pharm Sci. 2001;90:194–201. doi: 10.1002/1520-6017(200102)90:2<194::aid-jps10>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H, Jiang SP, Du YZ, Miao J, Zhang XG, Hu FQ. Strategic approaches for improving entrapment of hydrophilic peptide drugs by lipid nano-particles. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2009;70:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]