Abstract

6S RNA was identified in Escherichia coli >30 years ago, but the physiological role of this RNA has remained elusive. Here, we demonstrate that 6S RNA-deficient cells are at a disadvantage for survival in stationary phase, a time when 6S RNA regulates transcription. Growth defects were most apparent as a decrease in the competitive fitness of cells lacking 6S RNA. To decipher the molecular mechanisms underlying the growth defects, we have expanded studies of 6S RNA effects on transcription. 6S RNA inhibition of σ70-dependent transcription was not ubiquitous, in spite of the fact that the vast majority of σ70-RNA polymerase is bound by 6S RNA during stationary phase. The σ70-dependent promoters inhibited by 6S RNA contain an extended −10 promoter element, suggesting that this feature may define a class of 6S RNA-regulated genes. We also discovered a secondary effect of 6S RNA in the activation of σS-dependent transcription at several promoters. We conclude that 6S RNA regulation of both σ70 and σS activities contributes to increased cell persistence during nutrient deprivation.

For many years, it was thought that the wealth in number and function of untranslated small RNAs (sRNAs) was unique to eukaryotes. However, searches for sRNA genes in Escherichia coli, together with growing insight into their functions, have revealed that sRNAs are numerous, integral components of bacterial metabolism (17, 20, 33, 44, 45). The sophistication of bacterial sRNAs is exemplified by those that regulate gene expression, often providing critical changes in response to diverse environmental growth conditions (33, 45). For example, Spot42 RNA and CsrB RNA have roles during growth on various carbon sources (37, 42), and RyhB RNA responds to changes in iron availability (32). Other sRNAs respond to more immediate stresses, including hydrogen peroxide (OxyS RNA) (3), cold (DsrA RNA) (28, 41), and osmotic shock (RprA RNA and DsrA RNA) (30, 31).

6S RNA was the first sRNA to be sequenced >30 years ago (8). 6S RNA is processed out of a dicistronic transcript (22), although the mechanism for processing is unknown. The function of ygfA, an open reading frame within the 3′ end of the transcript, is also unknown. It was not until the discovery that 6S RNA interacts with RNA polymerase (RNAP) that the first hints of the 6S RNA function were revealed (47). 6S RNA interacts specifically with the σ70-containing form of RNAP (Eσ70), where the RNA makes direct contact with the σ70 subunit. The 6S RNA accumulates to high levels during stationary phase, at which time >75% of Eσ70 is complexed with 6S RNA (47). Therefore, the 6S RNA-RNAP complex is the predominant form of Eσ70 in cells following their transition into stationary phase.

Bacterial RNAP is a multisubunit enzyme composed of β, β′, ω, and two α subunits, in addition to a σ subunit required for transcription initiation. Many RNAP interactions with promoter DNA are well defined based on >3 decades of biochemical, genetic, and biophysical analyses, including several high-resolution structures of RNAP (reviewed in references 6, 38, and 49). σ subunits are key players in the recognition and binding of RNAP to promoters during transcription initiation and directly mediate several of the interactions between RNAP and DNA (18). At specific promoters, the contribution of each individual RNAP-DNA interaction to overall transcription efficiency, especially in combination with trans-acting factors, is variable and allows intricate control of the expression of individual promoters with or without trans-acting factors. For instance, promoters with “extended −10” sequence elements contain an additional conserved sequence (TGN) immediately upstream of the −10 element and exhibit decreased dependence on the −35 promoter element (7, 9, 36).

In addition to the constitutively abundant σ70, E. coli contains six sigma factors, many of which function in response to environmental cues (18). σS is an important regulator for establishing and surviving stationary phase (19, 23). σS remains at least 3-fold less abundant than σ70, and σ70-dependent transcription is down-regulated at least 10-fold in stationary phase (24). Eσ70 and EσS activities respond differently to chemical environments, DNA supercoiling, modification of RNAP, and trans-acting proteins (19, 23), suggesting that these variables contribute to relative EσS and Eσ70 activities in stationary phase. Other studies support direct competition in which σS outcompetes σ70 for core binding (11, 27); however, questions regarding relative abundances and core affinities suggest that the full complexity of σ70 versus σS regulation remains unknown.

During the transition from exponential to stationary phase, cells undergo a variety of morphological and physiological changes that assist them in survival as preferred nutrient pools are depleted (14, 15, 19, 39). Upon continued incubation, E. coli is able to survive for exceptionally long periods (years) without input of exogenous nutrients (reviewed in references 14 and 15). It has been shown that long-term survival is due in part to population heterogeneity arising from genetic mutations that confer increased fitness on dominant subpopulations of cells until other, more competitive mutants arise. This process of “waves of takeover” of cells with increased fitness has been called the growth advantage in stationary phase (GASP) phenotype (50).

We show here that 6S RNA function leads to increased cell survival during nutrient deprivation. In stationary phase, 6S RNA interaction with RNAP leads to inhibition of σ70-dependent transcription with a high degree of promoter specificity. Additionally, cells containing 6S RNA have increased σS-dependent transcription, although this increase is likewise promoter specific. We have established 6S RNA as a gene-specific trans-acting regulator of transcription, as well as an additional player involved in control of the relative utilization of σ70 and σS during stationary phase. We suggest that a combination of inappropriate σ70 and σS activities in 6S RNA-deficient cells is responsible for their decreased ability to survive extended nutrient deprivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

Strains were grown in Lennox Luria broth (LB) or M9 minimal medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose and 0.002% vitamin B1 (43). LB was unsupplemented unless otherwise indicated. For buffered LB, a final concentration of 100 mM MOPS [3-(4-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid], pH 7.0, was used. Ampicillin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), tetracycline (10 μg/ml), streptomycin (10 μg/ml), or nalidixic acid (15 μg/ml) was added when needed, as indicated. All cultures were grown on rotating platform shakers at ∼250 rpm. Cell culture volumes of 5 to 10 ml were grown in 16-mm-long tubes shaken at a 45° angle to the platform shaker; cell culture volumes of 50 ml were grown in 250-ml flasks.

P1 transductions were carried out as described previously (43) to move ssrS1 (29) and rpoS::Tn10 (2) into various strain backgrounds. Although the 6S RNA null mutation used here was originally called ssr1 (29), for clarity we will refer to it as ssrS1 (since the 6S RNA-encoding gene is ssrS). See Table 1 for the names and genotypes of the strains used. pKK* and pKK-6S* are an empty vector and a 6S RNA-expressing vector, respectively (47). For single-copy chromosomal reporter constructs, promoter regions were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA and cloned into pMSB1, followed by generation of λ phage lysogens using system II as described previously (40). Two previously constructed promoter-lacZ fusions (RLG6641 and RLG4418) were generated using λ system I (40). The extents of the promoter regions examined are indicated as numbers of nucleotides upstream and downstream of the +1 transcription start site (Table 1). For appY-lacZ and hya-lacZ, the distances are from the predicted start sites (1, 34). The galP1 and galP2 constructs contain point mutations to allow analysis of each promoter individually (Table 1) (10).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| Strain name | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ZK1142 | W3110 ΔlacU169 tna-2 [Nalr] | 51 |

| KW370 | ZK1142 ssrS1 [Nalr Ampr] | This work |

| ZK1143 | W3110 ΔlacU169 tna-2 [Strr] | 51 |

| KW371 | ZK1143 ssrS1 [Strr Ampr] | This work |

| KW72 | Laboratory wild-type strain background | 47 |

| GS075 | KW72 ssrS1 [Ampr] | 47 |

| RLG3499 | MG1655 pyrE+lacI lacZ [VH1000] | 16 |

| KW372 | RLG3499 λrsdP2(−149+91)-lacZ | This work |

| KW373 | KW372 ssrS1 | This work |

| RLG4998 | RLG3499 λlacUV5(−59+36)-lacZ | 5 |

| KW234 | RLG4998 ssrS1 | This work |

| RLG6358 | RLG3499 λrrnBP1(−41+1)-lacZ | 21 |

| KW238 | RLG6358 ssrS1 | This work |

| RLG6641 | RLG3499 λi21 lambdaPR(−40+20)-lacZ | 4 |

| KW325 | RLG6641 ssrS1 | This work |

| RLG5079 | RLG3499 λRNA1(−60+1)-lacZ | M. M. Barker and R. L. Gourse, unpublished data |

| KW321 | RLG5079 ssrS1 | This work |

| KW374 | RLG3499 λgalP1(−94+45)(−19G-T)-lacZ | This work |

| KW375 | KW374 ssrS1 | This work |

| KW376 | RLG3499 λgalP2(−89+50)(−37C-T)-lacZ | This work |

| KW377 | KW376 ssrS1 | This work |

| RLG3760 | RLG3499 λbolA1(−54+16)-lacZ | 16 |

| KW378 | RLG3760 ssrS1 | This work |

| RLG5852 | RLG3760 rpoS::Tn10 | 16 |

| KW380 | KW378 rpoS::Tn10 | This work |

| RLG5852 | RLG3499 λcc-35con(−40+2)-lacZ | 16 |

| KW381 | RLG5852 ssrS1 | This work |

| RLG5857 | RLG5852 rpoS::Tn10 | 16 |

| KW383 | KW381 rpoS::Tn10 | This work |

| KW384 | RLG3499 λhya (−279+27)-lacZ | This work |

| KW385 | KW384 ssrS1 | This work |

| KW386 | KW384 rpoS::Tn10 | This work |

| KW387 | KW385 rpoS::Tn10 | This work |

| KW388 | RLG3499 λappY(−685+12)-lacZ | This work |

| KW389 | KW388 ssrS1 | This work |

| KW390 | KW388 rpoS::Tn10 | This work |

| KW391 | KW389 rpoS::Tn10 | This work |

| KW392 | RLG3499 λrsdP1(−95+33)-lacZ | This work |

| KW393 | KW392 ssrS1 | This work |

| KW394 | KW392 rpoS::Tn10 | This work |

| KW395 | KW393 rpoS::Tn10 | This work |

| SG30013 | MG1655 Δlac λrpoS-lacZ | 46 |

| KW396 | SG30013 ssrS1 | This work |

Competition assay.

For standard competition experiments (see Fig. 1), approximately equal numbers of cells from fresh overnight cultures of each cell type were used to inoculate a 5-ml culture, similar to methods used to assess the relative cell fitness of various mutants (13, 48). Overnight cultures were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05 (∼5 × 107 cells), which was generally an ∼1:100 dilution. The actual number of input cells was determined by plating of dilutions from the inoculated culture (zero time) to verify OD600 measurements, as it was imperative to know the precise starting number of each cell type. For ≤24-h cultures, we found good agreement between the cell numbers determined by OD600 and plating assays. Cocultures were grown at 37°C, and the number of each cell type was determined by plating, usually once per day for 5 days.

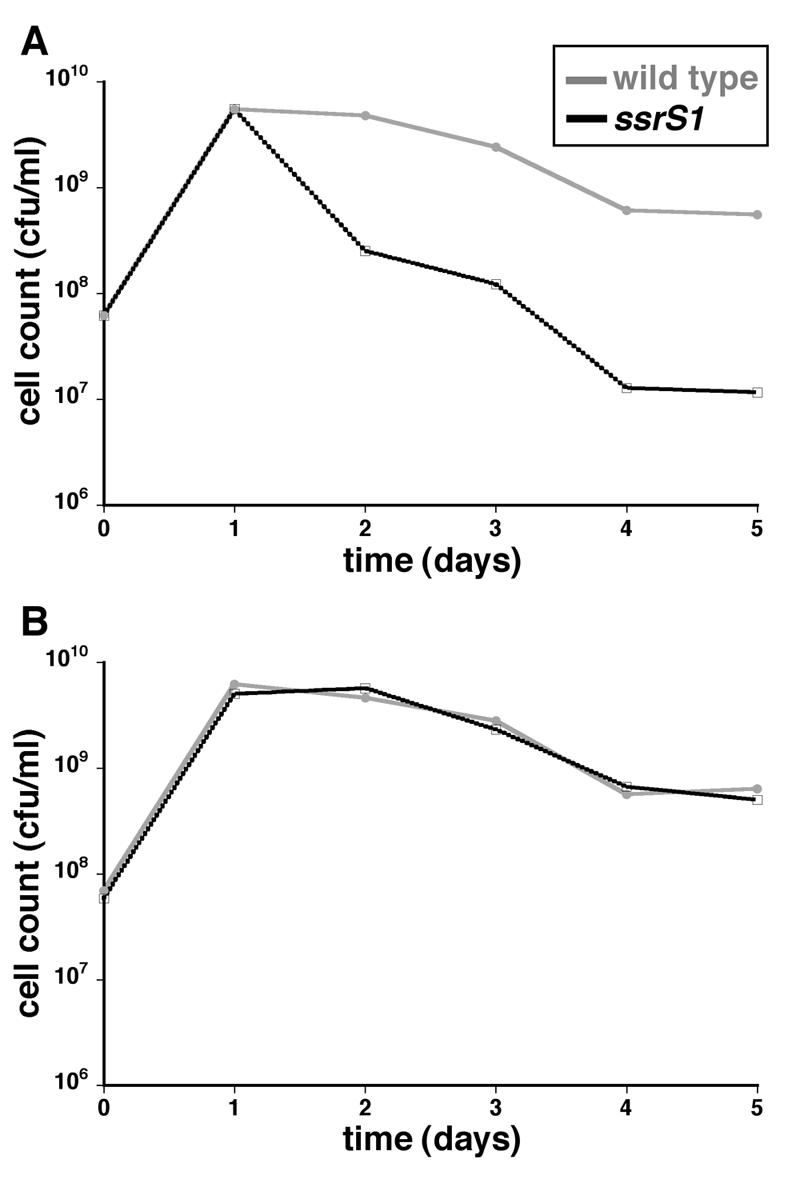

FIG. 1.

6S RNA-deficient cells (ssrS1) are at a competitive disadvantage after 2 days of growth in stationary phase. (A) Equal numbers of 6S RNA null cells and wild-type cells were inoculated into LB medium and incubated at 37°C, and viable-cell counts were measured over time by plating. The data presented are averages for five duplicate cultures of KW370 (ssrS1 Nalr) cocultured with ZK1143 (wild type, Strr) and five duplicate cultures of KW371 (ssrS1 Strr) and ZK1142 (wild type, Nalr). Standard deviations were small enough not to be visible on the log scale. (B) 6S RNA-deficient cells and wild-type cells were inoculated into individual cultures (not in competition) and incubated at 37°C, and cell densities were measured over time by plating. The data shown are from a representative experiment containing two duplicates of each cell type: ZK1142, ZK1143, KW370, and KW371.

In competition experiments, two strain backgrounds (ZK1142 and ZK1143) differing only in distinguishable drug markers, Nalr and Strr, respectively, were typically used so that cell populations could be detected independently by plating them on nalidixic acid- or streptomycin-containing plates. For example, in competitions between KW371 and ZK1142, colonies formed on streptomycin-containing plates indicated the number of KW371 cells in the culture, while colonies formed on nalidixic acid plates indicated the number of ZK1142 cells. We did not detect any difference in growth or survival of the marked strain backgrounds (ZK1142 and ZK1143) when they were cultured alone or in direct competition (data not shown) as previously reported (51). In addition, all competition experiments were done in both combinations of strain backgrounds (i.e., ZK1143 versus KW370 and ZK1142 versus KW371) with identical results. To test any strain background variations, and in particular to examine growth phenotypes in the cells previously used for 6S RNA molecular and biochemical experiments (47), competition experiments also were done using GS075 (ssrS1) and KW72 (wild type). KW72 does not carry a drug resistance gene; therefore, viable-cell counts were monitored by plating cells on LB-ampicillin plates (ssrS1 cells) and LB plates (wild-type plus ssrS1 cells), and wild-type cell numbers were inferred as the difference.

Changes to this general protocol included inoculation with unequal numbers of competing cells (10:1 or 100:1). Once again, the number of cells used for inoculation was based on OD600 readings but also verified by plating to determine the actual input cell numbers. Cocultures were initiated by mixing equal numbers of cells from stationary-phase cultures (24 to 48 h) without dilution in fresh medium. Conditioned medium from 24-h cultures was removed from the cells by centrifugation (3,000 × g; 10 min at 4°C) or by killing cells in medium by heating them at 65°C for 2 h (12), with similar results. Conditioned media were free of living cells as determined by plating.

For competition experiments using different-age cultures (see Fig. 3), the same number of each cell type was used to inoculate cocultures (∼5 × 107 cells). The cell density of the 10-day cultures was estimated to be the same as the cell density of the cultures determined at 9 days by plating. The cell density of 1-day cultures was estimated from the OD600 reading. Actual input cell numbers were determined by plating of the inoculated cultures at time zero. Note that these competition experiments were initiated with equal numbers of cells to more closely resemble our standard competition experiments, which is in contrast to the original experiments describing GASP mutants, in which aged cells were a minority population (51).

FIG. 3.

Both wild-type and ssrS1 cells exhibit GASP phenotypes; 10-day cultures are able to outcompete 1-day cultures from matched strain backgrounds. Wild-type (A) or ssrS1 (B) cultures were inoculated into LB medium and grown at 37°C for 10 days. On the ninth day, fresh wild-type or ssrS1 cultures were inoculated into fresh LB medium so that a 1-day culture and a 10-day culture would be ready at the same time. Equal numbers of 10-day and 1-day cells were mixed into a single culture and grown at 37°C, and viable-cell counts were monitored over time by plating. The data shown are averages from one experiment each with ZK1143 (10 day) versus ZK1142 (1 day) and ZK1142 (10 day) versus ZK1143 (1 day) (A), or three experiments with KW370 (10 day) versus KW371 (1 day) and one with KW371 (10 day) versus KW370 (1 day) (B).

Plating assay.

For each time point, 10 to 40 μl was removed from the cocultures, serially diluted in M9 salts, and spread on LB plates containing the appropriate antibiotics (see above), and the number of viable cells was determined as the number of colonies formed. Plates from dilutions that gave ∼100 to 250 colonies per plate were used to minimize statistical variation due to small sample sizes. These numbers allow accuracy down to at least twofold changes. Typically, three to five replicates of each coculture were done per experiment, and experiments were repeated a minimum of three times. The experiments exhibited a high degree of reproducibility, so that the standard deviation was too small to be easily visible when graphed on a log scale (see Fig. 1 to 3).

Long-term growth.

To monitor cell persistence, colonies from fresh plates were used to inoculate 50- or 10-ml cultures in LB. The cells were grown at 37°C on a continuously shaking platform. Viable-cell counts were determined periodically by plating cells onto LB plates (without antibiotics). Sterile water was added to cultures as needed to combat evaporation with no apparent immediate effect on cell survival. For example, in one experiment (see Fig. 2), water was added in the following manner to maintain a constant volume of 50 ml: 5 ml at 99 days, 8 to 12 ml at 135 days, and 7 to 10 ml at 170 days.

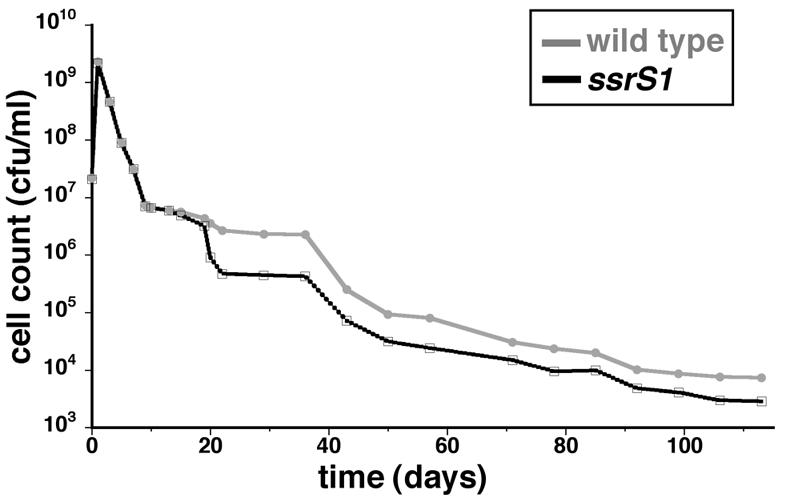

FIG. 2.

6S RNA-deficient cells are defective for persistence after 3 weeks in batch culture. KW72 (wild-type) or GS075 (ssrS1) cells were inoculated into LB medium and grown at 37°C without addition of exogenous nutrients. At the times indicated, viable-cell counts were measured by plating. The data shown are from one representative experiment with three duplicate cultures of each strain from 1 to 57 days, at which time one of the ssrS1 cultures was lost. Therefore, for >57 days, there were two duplicate cultures of ssrS1 and three of the wild type. Similar patterns of cell persistence were seen with ZK1142, ZK1143, KW30, and KW371 examined from 1 to 60 days in three independent experiments.

The overall cell survival, especially the timing and pattern of changes in cell counts, was very reproducible from experiment to experiment with no detectable dependence on the initial culture volumes (10 or 50 ml) or the different strain backgrounds reported here (ZK1142, ZK1143, or KW72) (data not shown). Our long-term patterns of cell survival are similar to published growth patterns of the ZK1142, ZK1143, or parental ZK126 strain (13, 15, 48, 51), although minor variations in the exact timing and extent of cell density decreases were observed, probably due to slight differences in aeration of cultures, medium preparation, or general laboratory environments beyond our control over the time course of this type of experiment.

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase activity assays were done at 30°C as previously described, and activity is expressed in Miller units (ΔOD420 per min per OD600 unit) (35). Cells were grown from a single colony in LB medium at 30°C for 24 h, diluted 1:100 in fresh LB medium, and assayed after continued growth for 18 h at 30°C. At least three independent cultures per strain were used for each experiment, and experiments were repeated at least three times. When cells contained a plasmid (Fig. 4A), LB supplemented with chloramphenicol was used.

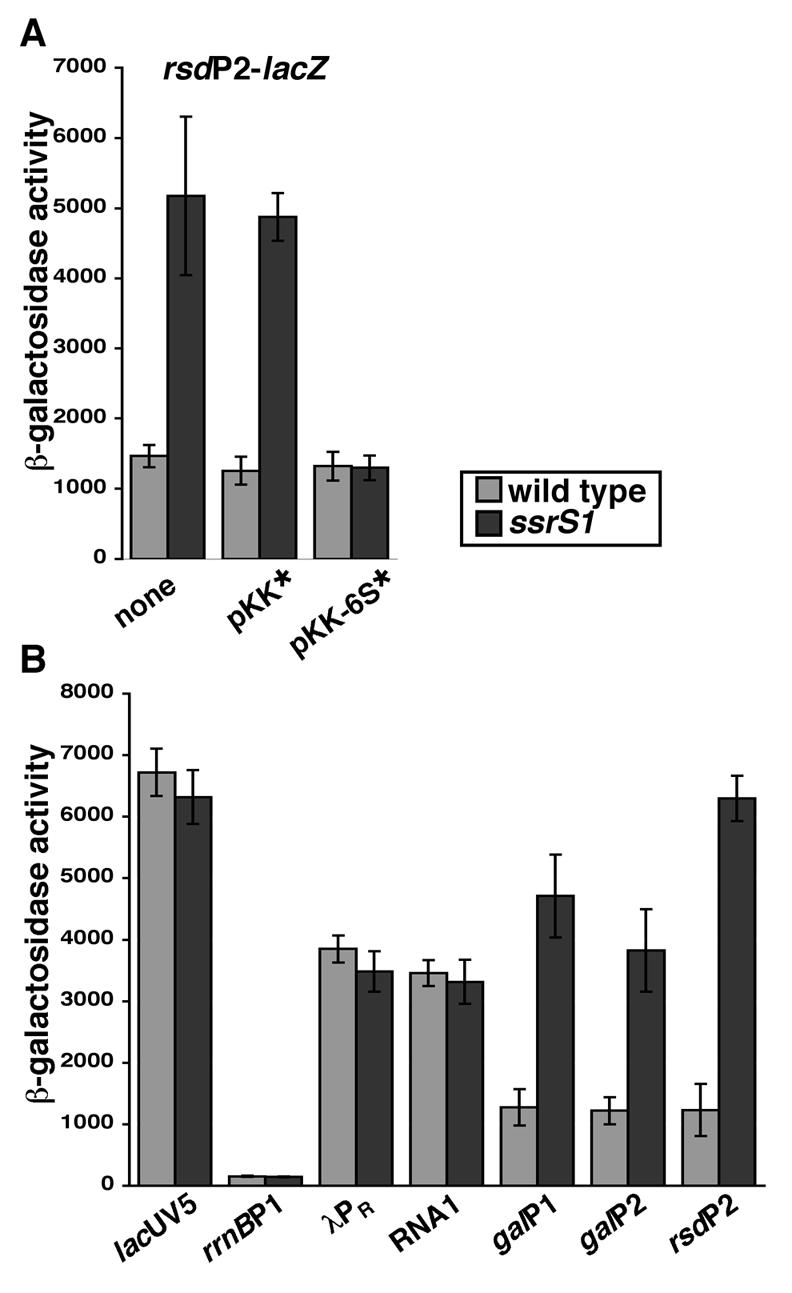

FIG. 4.

6S RNA inhibits transcription from several, but not all, σ70-dependent promoters. The β-galactosidase activities of various promoters were measured in wild-type or ssrS1 strain backgrounds. (A) Expression from rsdP2 at 18 h of growth in LB medium at 30°C in wild-type or ssrS1 strain backgrounds alone, in the presence of an empty vector (pKK*), or in the presence of a 6S RNA-expressing vector (pKK-6S*). (B) The β-galactosidase activities of several σ70-dependent promoters (lacUV5-lacZ, rrnBP1-lacZ, λPR-lacZ, RNA1-lacZ, galP1-lacZ, galP2-lacZ, and rsdP2-lacZ) in wild-type or ssrS1 strain backgrounds grown for 18 h in LB medium at 30°C were examined. Data are averages (with error bars corresponding to ± standard deviations from the averages) of at least three experiments, with three duplicates per experiment. β-Galactosidase activity is expressed in Miller units.

Primer extension assays.

RNA was isolated from cells grown for 18 h at 30°C (the same as for β-galactosidase activity) using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) as previously described (47). Primer extension was done using SuperscriptII (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol for first-strand synthesis, except that 10 μg of total RNA and 2 ng of oligonucleotide (AGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGACGTTG), after 5′-end labeling with polynucleotide kinase (New England Biochemicals) and [γ-32P]ATP (46), were used per reaction. Extension products were separated on 8% polyacrylamide denaturing gels and visualized and quantitated using a Storm 860 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS

Cells without 6S RNA are at a competitive disadvantage in stationary phase.

6S RNA binds to the majority of Eσ70 during stationary phase (47), suggesting a physiological role for 6S RNA at this time. However, growth phenotypes of 6S RNA null cells (ssrS1) have not been detected in entry, exit, or maintenance of stationary phase for up to 10 days (29, 47). In addition, ssrS1 cell morphology is indistinguishable from the wild type in exponential-phase to 24-h cultures as visualized by microscopy (data not shown). Here, we expand on these studies by examining competitive growth and longer periods of nutrient deprivation.

Cocultures were inoculated with equal numbers of ssrS1 and wild-type cells containing neutrally marked chromosomes (KW370 and ZK1143; KW371 and ZK1142) (Fig. 1A) in LB medium at 37°C to address the competitive fitness of ssrS1 cells. The number of each cell type remaining over time was monitored by differential plating (see Materials and Methods). ssrS1 and wild-type cells maintained equal numbers through the first day of competitive growth, but ssrS1 cells decreased 20-fold compared to wild-type cells by 2 to 3 days in coculture and ∼70-fold after 3 days, indicating that ssrS1 cells are at a disadvantage. ssrS1 cells and wild-type cells cultured independently exhibit indistinguishable growth curves (Fig. 1B). Similar profiles of competitive and noncompetitive growth were seen when cocultures or independent cultures were inoculated with the isogenic ssrS1 and wild-type cells (GS075 and KW72) (data not shown).

To examine whether competitive growth through exponential phase was required for the observed growth defect, cocultures were initiated by mixing equal numbers of ssrS1 and wild-type cells (KW371 and ZK1142) from independent 48-h cultures without addition of fresh medium. ssrS1 cells decreased compared to wild-type cells (data not shown), indicating that the initiation of competition in exponential phase was not necessary. Likewise, specific growth medium was not required, as ssrS1 cells decreased relative to wild-type cells when cocultured in buffered LB medium (pH 7.0) or minimal media (M9-glucose and M9-glycerol) (KW371 and ZK1142; KW370 and ZK1143) (data not shown). To test the possibility that wild-type cells were making and secreting a factor responsible for decreased fitness of ssrS1 cells, we compared levels of growth in media conditioned from 24-h cultures. Specifically, cells (GS075 or KW72) collected by centrifugation from a 24-h culture were resuspended in medium removed from a 24-h culture (KW72 or GS075), and the number of cells remaining was monitored over four additional days. ssrS1 and wild-type cell numbers were indistinguishable from one another whether the cells were grown in ssrS1-conditioned medium or wild-type-conditioned medium (data not shown), suggesting that the ssrS1 disadvantage in competition was not due to a stable factor excreted by wild-type cells.

The ssrS1 cells were at a disadvantage even when cocultures were inoculated with a 10:1 or 100:1 ratio of ssrS1 cells to wild-type cells (KW370-ZK1143 and KW371-ZK1142). In each case, wild-type cells gained in relative abundance and reached equal representation with ssrS1 cells by 2 to 3 days (data not shown). In contrast, wild-type cells inoculated at 100:1 ratios into cocultures (ZK1142-ZK1143 and ZK1143-ZK1142) resulted in the minority cells remaining at least 100-fold underrepresented in the population (data not shown).

6S RNA is required for maximal persistence in stationary phase for >20 days.

We next examined ssrS1 and wild-type cell survival when cells were cultured independently in LB medium at 37°C for months to test if a growth defect in 6S RNA-deficient cells would be revealed at later times (Fig. 2). ssrS1 (KW370, KW371, or GS075) and wild-type (ZK1142, ZK1143, or KS72) cultures were indistinguishable for at least 2 weeks after the initial inoculation. Viable-cell counts were determined by plating assays and revealed that ssrS1 cells decreased ∼5-fold relative to wild-type cells from 3 to 5 weeks. After 5 weeks, ssrS1 cells maintained ∼3-fold lower cell counts than wild-type cells for many months (we have followed cultures for up to 8 months). Although there were minor variations in absolute cell counts from experiment to experiment, the overall patterns of changes for ssrS1 and wild-type cells were consistent, especially in the timing and magnitude of changes.

6S RNA-deficient cells maintain the ability to exhibit a GASP phenotype.

The long time frame for appearance of ssrS1 growth defects and their disadvantage in competitive growth led us to consider whether ssrS1 cells were deficient in acquiring GASP phenotypes (reviewed in references 14 and 15). GASP phenotypes were originally described as the ability of 10-day cultures of wild-type cells to outcompete a 1-day culture of wild-type cells (51). We found that 10-day ssrS1 cells cocultured with 1-day ssrS1 cells (KW37010 day-KW3711 day or KW37110 day-KW3701 day) resulted in the 1-day ssrS1 cells decreasing in relative abundance, indicating that ssrS1 cells are capable of GASP behavior (Fig. 3A). For comparison, we examined wild-type cells and found that 10-day wild-type cells efficiently outcompeted 1-day wild-type cells (ZK114210 day-ZK11431 day or ZK114310 day-ZK11421 day), similarly to ssrS1 (Fig. 3B) and as previously reported (51). We next cocultured 10-day ssrS1 cells with 1-day wild-type cells (KW37010 day-ZK114310 day or KW37110 day-ZK114210 day) and found that the 10-day ssrS1 cells were not able to overtake the 1-day wild-type cells (data not shown). However, after 5 days of coculture, the ssrS110 day cells were only 3-fold underrepresented, compared to ∼70-fold for the ssrS11 day cells cocultured with 1-day wild-type cells (Fig. 1A).

6S RNA alters transcription from some, but not all, σ70-dependent promoters.

It was previously discovered that 6S RNA inhibits σ70-dependent transcription, at least as monitored by expression from the rsdP2 promoter of the endogenous rsd gene (47) and by expression from rsdP2 in vitro (K. M. Wassarman, unpublished data). To probe the extent of 6S RNA inhibition of transcription that might account for the described growth defects, we examined 6S RNA effects on transcription at several different promoters (see below). All promoters examined were single-copy promoter-lacZ fusions to allow monitoring of expression over time via β-galactosidase activity. Expression from rsdP2-lacZ in wild-type cells (KW372) remained constant throughout 24 h of growth. However, in ssrS1 cells (KW373), expression from rsdP2-lacZ was similar to that from the wild type in exponential phase but increased upon transition into stationary phase and remained elevated thereafter (data not shown). At 18 h, rsdP2-lacZ expression was increased by three- to fourfold in ssrS1 compared to the wild-type strain background (Fig. 4A), which was the largest difference observed. The three- to fourfold change was comparable to the 6S RNA-dependent change in expression observed from the chromosomal rsdP2 promoter using an RNase protection assay (47), and a three- to fivefold change in mRNA generated from the rsdP2-lacZ reporter in ssrS1 compared to wild-type strain backgrounds as examined by primer extension (data not shown). Therefore, subsequent experiments examining other promoter activities were done at 18 h. Wild-type expression of rsdP2-lacZ was restored in ssrS1 cells by introduction of a 6S RNA-expressing plasmid (pKK-6S*), but not a plasmid control (pKK*), confirming that changes in rsdP2-lacZ expression were due to changes in 6S RNA levels (Fig. 4A). Western analysis revealed that there was no change in core RNAP subunit or σ70 protein levels in ssrS1 (GS075) compared to the wild type (KW72) over several days of growth (data not shown).

As 6S RNA interacts with the vast majority of Eσ70 in stationary phase, the possibility existed that general σ70-dependent transcription would be decreased by 6S RNA at this time. However, expression of several well-studied σ70-dependent promoters (lacUV5-lacZ, rrnBP1-lacZ, λPR-lacZ, and RNA1-lacZ) revealed equivalent levels of expression in ssrS1 and wild-type strain backgrounds at 18 h (Fig. 4B). To ensure that β-galactosidase activity was representative of mRNA levels and thus transcription activity at the times tested, primer extension analysis was done to examine mRNA from lacUV5-lacZ and RNA1-lacZ in wild-type and ssrS1 strain backgrounds at 18 h of growth. In both cases, the levels of extension product for each reporter gene were equal in ssrS1 and wild-type cells, indicating no change in mRNA levels and correlating with the lack of change in β-galactosidase activity. Therefore, 6S RNA does not inhibit transcription of all σ70-dependent promoters in stationary phase.

rsdP2 contains an extended −10 promoter element (26), so we tested additional extended −10-containing promoters (galP1 and galP2) to examine whether this promoter element might define a class of promoters inhibited by 6S RNA. Indeed, expression from galP1-lacZ and galP2-lacZ, which each contain extended −10 elements (7), increased by >3-fold in ssrS1 cells compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 4B).

6S RNA also affects σS-dependent transcription.

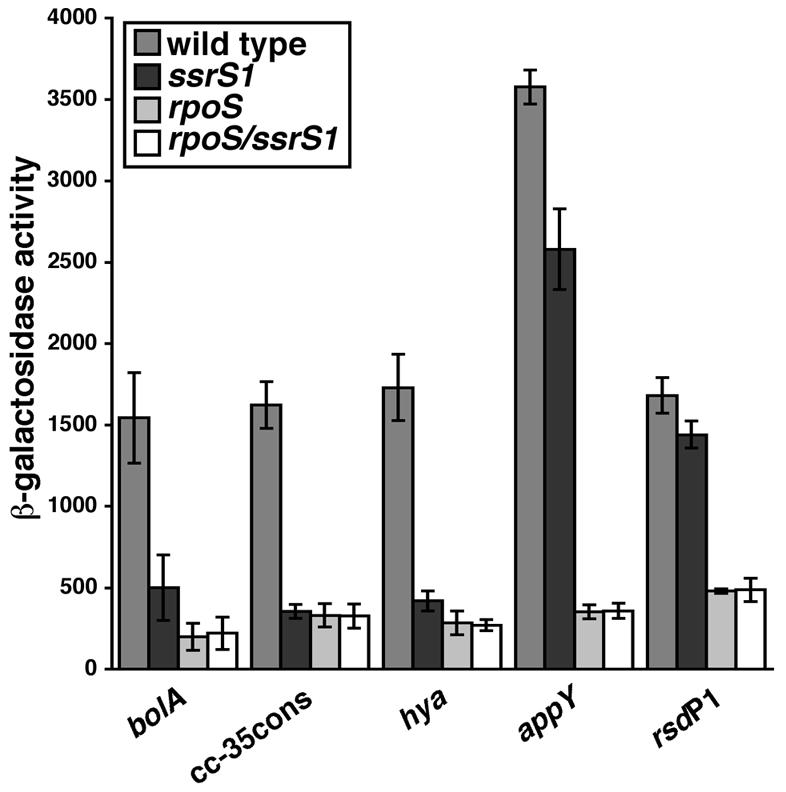

To expand our understanding of potential 6S RNA-dependent alterations in transcription, we next examined whether 6S RNA affects σS-dependent transcription, as σS is a key regulator during stationary phase when 6S RNA function appears to be most important. We observed that expression from the σS-dependent promoter, bolA-lacZ, was decreased in ssrS1 cells by three- to fourfold compared to wild-type cells, suggesting that the presence of 6S RNA activated its transcription (Fig. 5). Expression of 6S RNA from a plasmid (pKK-6S*) but not a plasmid control (pKK*) restored wild-type expression (data not shown). Similarly, expression from the σS-dependent promoters cc-35con-lacZ (an artificial promoter [16]) and hya-lacZ was decreased in the ssrS1 strain background. However, another σS-dependent promoter, appY-lacZ, exhibited a smaller, if any, decrease in the ssrS1 strain background. Previously, the expression from the endogenous rsdP1 (a σS-dependent promoter) had been found to be insensitive to the presence of 6S RNA (47), although the experiments reported may not have been sensitive to small changes, as they were designed to evaluate the relative utilization of the σ70-dependent promoter (rsdP2) compared to the σS-dependent promoter (rsdP1). Reexamination of this promoter via expression from rsdP1-lacZ showed that levels of expression are comparable in ssrS1 and wild-type strains (Fig. 5), consistent with earlier findings. Expression from bolA-lacZ, cc-35con-lacZ, hya-lacZ, appY-lacZ, and rsdP1-lacZ was dramatically reduced in rpoS strain backgrounds, confirming their σS dependence (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Presence of 6S RNA leads to activation of some σS-dependent promoters. Shown are the β-galactosidase activities of σS-dependent promoters (bolA-lacZ, cc-35con-lacZ, hya-lacZ, appY-lacZ, and rsdP1-lacZ) in the wild-type, ssrS1, rpoS, and ssrS1/rpoS strains grown for 18 h at 30°C in LB medium. All data are averages (with error bars corresponding to ± standard deviations from the averages) of at least three experiments, with three duplicates per experiment. β-Galactosidase activity is expressed in Miller units.

To determine whether changes in σS-dependent transcription might reflect changes in σS protein levels in ssrS1 strain backgrounds, expression of rpoS was examined in ssrS1 and wild-type backgrounds from an rpoS-lacZ operon fusion reporter. No difference in activity was detected, indicating that transcription of rpoS was not altered by 6S RNA (data not shown). In addition, Western analysis of σS protein in ssrS1 (GS075) and wild-type strain backgrounds (KW72) revealed that σS protein levels were comparable (data not shown) and indicated that observed changes in σS-dependent transcription were not a result of changes in σS protein levels.

DISCUSSION

We have identified a growth phenotype for 6S RNA-deficient cells: they are at a competitive disadvantage compared to wild-type cells after 2 days of growth, and they exhibit decreased persistence in stationary phase after ∼3 weeks of growth when not in competition. Given that 6S RNA interacts with RNAP and alters transcription, we speculate that these growth defects result from 6S RNA-dependent changes in gene expression. We have determined that σ70-dependent promoters are not equally inhibited by 6S RNA in spite of the fact that the majority of Eσ70 is bound by 6S RNA in stationary phase. A common feature of σ70-dependent promoters inhibited by 6S RNA identified here is an extended −10 promoter element. In addition to the direct effect of 6S RNA on Eσ70, we have discovered that EσS activity is activated when cells contain 6S RNA, although 6S RNA does not interact directly with EσS (47; Wassarman, unpublished). We conclude that growth defects of 6S RNA-deficient cells most likely result from the inappropriate control of both σ70- and σS-dependent gene expression.

Loss of 6S RNA leads to decreased survival compared to wild-type cells.

When grown independently, 6S RNA null and wild-type cells appear to enter stationary phase and maintain stationary phase for many days indistinguishably from one another; however, when they are grown in direct competition, the 6S RNA null cells are at a distinct disadvantage within 2 days. The mechanism responsible for the decreased fitness of 6S RNA-deficient cells is expected to occur during stationary phase, as competitive growth in exponential phase is not required for the observed defects. It is also possible that the timing of the growth phenotypes represents a time frame of cell sensitivity to defects established earlier. The loss of competitive fitness is not due to a stable factor secreted from wild-type cells, as ssrS1 cells were unaffected by medium conditioned by wild-type cells at a time when mixture with the full wild-type culture is deleterious. One hypothesis for the direct consequences of competitive growth is that ssrS1 cells are unable to efficiently compete for the remaining resources.

6S RNA null cells also are defective in long-term persistence (>20 days) when grown independently. We observed substantial 6S RNA-dependent changes in transcription by 18 h, raising important questions as to why growth defects are delayed. One possibility is that the timing of the growth defects represents sensitivity to environmental conditions at that time but that this sensitivity was established much earlier as a consequence of altered gene products. For instance, if a primary nutrient source at 3 weeks of growth cannot be properly utilized by ssrS1 cells, this could account for the decrease in cell numbers. However, ssrS1 cells are able to persist similarly to wild-type cells in conditioned medium prepared from 20-day wild-type cells (A. E. Trotochaud and K. M. Wassarman, unpublished data), suggesting that this is probably not the case.

A second possibility is that the decrease in ssrS1 cell numbers at 20 days might be due to the presence of a deleterious by-product of metabolism that would normally not be generated or that cannot be properly disposed of in the ssrS1 cells. Alternatively, the ssrS1 cells may be less efficient at utilization of available nutrients and energy throughout growth, which might result in depletion of these sources earlier, leading to decreased cell densities. In either case, one would predict that 20-day ssrS1-conditioned medium would not support cell persistence as well as 20-day wild-type-conditioned medium, and preliminary data support this possibility (Trotochaud and Wassarman, unpublished). Further work is needed to distinguish between the potential presence of deleterious compounds and the absence of comparable nutrients as the cause for decreased cell numbers. It is also intriguing to speculate whether the decrease in numbers of ssrS1 cells at ∼3 weeks might be for reasons similar to those that normally cause wild-type cells to decrease at ∼5 weeks.

A third possibility is that 6S RNA-deficient cells are defective in processes that allow cells to gain fitness by genetic modification. For instance, changes in mutation rates could directly alter the time required for the generation of advantageous mutations. Although we have shown that ssrS1 cells are capable of generating GASP-phenotypic cells (Fig. 3), this may not reflect the efficiency with which these mutant cells arise and multiply. Further study of the timing and identity of GASP alleles generated between wild-type and ssrS1 cells may elucidate such differences.

6S RNA alters the transcription of some, but not all, genes in stationary phase.

We have discovered that specific σ70-dependent promoters respond distinctively to 6S RNA; some promoters are inhibited, while others remain unchanged. Therefore, 6S RNA is a transcriptional regulator during stationary phase. Our data suggest that one class of promoters inhibited by 6S RNA consists of promoters with extended −10 elements. One proposed model for 6S RNA action is that its binding to RNAP blocks normal RNAP binding to promoter DNA (45). The predicted 6S RNA structure is largely double stranded with a single-stranded bulged loop in the center, reminiscent of the DNA structure within the open complex. It is intriguing that one characteristic of extended −10 promoters is that they often have poor −35 sequence elements compared to the consensus and have a decreased dependence on the −35 element for recognition and binding of RNAP (7). Perhaps 6S RNA binding to RNAP alters the −10 region recognition or affinity, which cannot be overcome without strong −35 element contacts. Alternatively, 6S RNA-sensitive promoters may use a common trans-acting factor that is affected by 6S RNA or may contain additional defined sequences outside the core promoter elements. Identification of specific components responsible for 6S RNA inhibition, as well as further understanding of how 6S RNA alters RNAP physically, await future dissection of individual promoters and 6S RNA modification of RNAP.

6S RNA also can lead to activation of σS-dependent transcription from several, but not all, tested promoters. 6S RNA does not interact directly with EσS or σS, as shown by the inability to copurify σS with 6S RNA from stationary-phase cells when endogenous 6S RNA-Eσ70 complexes are efficiently purified (47). Additionally, interactions between 6S RNA and EσS or σS are not detectable by cross-linking experiments (47) or by in vitro reconstitution experiments that readily observe 6S RNA-Eσ70 complexes (Wassarman, unpublished). Therefore 6S RNA effects on σS-dependent transcription must be indirect. One model is that the effectiveness of σS competition for core RNAP is normally increased during late stationary phase by the presence of 6S RNA binding to the majority of Eσ70. Another possibility is that there is a trans-acting factor that is required for efficient σS-dependent transcription of sensitive promoters, which is decreased in 6S RNA-deficient cells, presumably through direct changes in σ70-dependent transcription.

Uncovering further characteristics of promoters responsive to 6S RNA inhibition or activation will lead to global identification of sensitive promoters. The next question will be how alterations in gene products controlled by these promoters contribute to decreased persistence of 6S RNA-deficient cells. Already, a potential link exists between 6S RNA function and 6S RNA regulation of rsd expression. The Rsd protein is an anti-sigma factor which specifically inactivates free σ70 (25), although Rsd levels are not high enough to account for full σ70 inhibition during stationary phase. It is possible that 6S RNA and Rsd activities coordinate to reach appropriate levels of σ70 activity, in part through 6S RNA regulation of rsd transcription. Interestingly, in addition to the upregulation of the σ70-dependent rsdP2 promoter, the rsdP1 promoter is the only σS-dependent promoter tested to date that is insensitive to 6S RNA, thus allowing maximal rsd expression from both promoters in the absence of 6S RNA. Recently, 106 promoters that contain extended −10 elements have been identified (36). If this promoter feature truly defines a class of 6S RNA-inhibited promoters, future work toward evaluating the overall contribution of 6S RNA alterations in expression of these and other genes may ultimately determine their roles in long-term cell survival.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. E. Finkel and R. L. Gourse for providing strains. We thank D. M. Downs, R. Landick, W. Ross, and G. Storz for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM67955).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altung, T., A. Nielsen, and F. G. Hansen. 1989. Isolation, characterization, and nucleotide sequence of appY, a regulatory gene for growth-phase-dependent gene expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:1683-1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altuvia, S., M. Almiron, G. Huisman, R. Kolter, and G. Storz. 1994. The dps promoter is activated by OxyR during growth and by IHF and σS in stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 13:265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altuvia, S., D. Weinstein-Fischer, A. Zhang, L. Postow, and G. Storz. 1997. A small stable RNA induced by oxidative stress: role as a pleiotropic regulator and antimutator. Cell 90:43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker, M. M., and R. L. Gourse. 2001. Regulation of rRNA transcription correlates with nucleoside triphosphate sensing. J. Bacteriol. 183:6315-6323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker, M. M., T. Gaal, C. Josaitis, and R. L. Gourse. 2001. Mechanism of regulation of transcription initiation by ppGpp. I. Effects of ppGpp on transcription initiation in vivo and in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 305:673-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borukhov, S., and E. Nudler. 2003. RNA polymerase holoenzyme: structure, function and biological implications. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:93-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bown, J. A., K. A. Barne, S. D. Minchin, and S. J. W. Busby. 1997. Extended −10 promoters, p. 41-52. In F. Eckstein and D. M. J. Lilley (ed.), Nucleic acids and molecular biology, vol. 11. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brownlee, G. G. 1971. Sequence of 6S RNA of E. coli. Nat. New Biol. 229:147-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burr, T., J. Mitchell, A. Kolb, S. Minchin, and S. Busby. 2000. DNA sequence elements located immediately upstream of the −10 hexamer in Escherichia coli promoters: a systematic study. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1864-1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busby, S., and M. Dreyfus. 1983. Segment-specific mutagenesis of the regulatory region in the Escherichia coli galactose operon: isolation of mutations reducing the initiation of transcription and translation. Gene 21:121-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farewell, A., K. Kvint, and T. Nyström. 1998. Negative regulation by RpoS: a case of sigma factor competition. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1039-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrell, M. J., and S. E. Finkel. 2003. The growth advantage in stationary phase phenotype conferred by rpoS mutations is dependent on the pH and nutrient environment. J. Bacteriol. 185:7044-7052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkel, S. E., and R. Kolter. 2001. DNA as a nutrient: novel role for bacterial competence gene homologs. J. Bacteriol. 183:6288-6293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkel, S. E., E. R. Zinser, and R. Kolter. 2000. Long-term survival and evolution in the stationary phase in Escherichia coli, p. 231-238. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 15.Finkel, S. E., E. R. Zinser, S. Gupta, and R. Kolter. 1997. Life and death in stationary phase, p. 3-16. In S. J. W. Busby, C. M. Thomas, and N. L. Brown (ed.), Molecular microbiology. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 16.Gaal, T., W. Ross, S. T. Estrem, L. H. Nguyen, R. R. Burgess, and R. L. Gourse. 2001. Promoter recognition and discrimination by EσS RNA polymerase. Mol. Microbiol. 42:939-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottesman, S. 2002. Stealth regulation: biological circuits with small RNA switches. Genes Dev. 16:2829-2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gruber, T. M., and C. A. Gross. 2003. Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:441-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2000. The general stress response in Escherichia coli, p. 161-178. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 20.Hershberg, R., S. Altuvia, and H. Margalit. 2003. A survey of small RNA-encoding genes in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:1813-1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirvonen, C. A., W. Ross, C. E. Wozniak, E. Marasco, J. R. Anthony, S. E. Aiyar, V. H. Newburn, and R. L. Gourse. 2001. Contributions of UP elements and transcription factor FIS to expression from the seven rrn P1 promoters in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:6305-6314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu, L. M., J. Zagorski, A. Wang, and M. J. Fournier. 1985. Escherichia coli 6S RNA gene is part of a dual-function transcription unit. J. Bacteriol. 161:1162-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishihama, A. 1999. Modulation of the nucleoid, the transcription apparatus, and the translation machinery in bacteria for stationary phase survival. Genes Cells 4:135-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishihama, A. 2000. Functional modulation of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:499-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jishage, M., and A. Ishihama. 1998. A stationary phase protein in Escherichia coli with binding activity to the major σ subunit of RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:4953-4958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jishage, M., and A. Ishihama. 1999. Transcriptional organization and in vivo role of the Escherichia coli rsd gene, encoding the regulator of RNA polymerase sigma D. J. Bacteriol. 181:3768-3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jishage, M., K. Kvint, V. Shingler, and T. Nyström. 2002. Regulation of σ factor competition by the alarmone ppGpp. Genes Dev. 16:1260-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lease, R. A., and M. Belfort. 2000. Riboregulation by DsrA RNA: trans-actions for global economy. Mol. Microbiol. 38:667-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, C. A., M. J. Fournier, and J. Beckwith. 1985. Escherichia coli 6S RNA is not essential for growth or protein secretion. J. Bacteriol. 161:1156-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majdalani, N., S. Chen, J. Murrow, K. St. John, and S. Gottesman. 2001. Regulation of RpoS by a novel small RNA: the characterization of RprA. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1382-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majdalani, N., C. Cunning, D. Sledjeski, T. Elliott, and S. Gottesman. 1998. DsrA RNA regulates translation of RpoS message by an anti-antisense mechanism, independent of its action as an antisilencer of transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:12462-12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masse, E., and S. Gottesman. 2002. A small RNA regulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4620-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masse, E., N. Majdalani, and S. Gottesman. 2003. Regulatory roles for small RNAs in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menon, N. K., J. Robbins, H. D. Peck, Jr., C. Y. Chatelus, E.-S. Choi, and A. E. Przybyla. 1990. Cloning and sequencing of a putative Escherichia coli [NiFe] hydrogenase-1 operon containing six open reading frames. J. Bacteriol. 172:1969-1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 36.Mitchell, J. E., D. Zheng, S. J. W. Busby, and S. D. Minchin. 2003. Identification and analysis of “extended −10” promoters in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:4689-4695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Møller, T., T. Franch, C. Udesen, K. Gerdes, and P. Valentin-Hansen. 2002. Spot42 RNA mediates discoordinate expression of the E. coli galactose operon. Genes Dev. 16:1696-1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murakami, K. S., and S. A. Darst. 2003. Bacterial RNA polymerases: the whole story. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13:31-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nyström, T. 1999. Starvation, cessation of growth and bacterial aging. Curr. Opin. Biol. 2:214-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rao, L., W. Ross, J. A. Appleman, T. Gaal, S. Leirmo, P. J. Schlax, M. T. Record, Jr., and R. L. Gourse. 1994. Factor independent activation of rrnBP1. An “extended” promoter with an upstream element that dramatically increases promoter strength. J. Mol. Biol. 235:1421-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Repoila, F., and S. Gottesman. 2001. Signal transduction cascade for regulation of RpoS: temperature regulation of DsrA. J. Bacteriol. 183:4012-4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romeo, T. 1998. Global regulation by the small RNA-binding protein Csr and the non-coding RNA molecule CsrB. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1321-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silhavy, T. J., M. L. Berman, and L. W. Enquist. 1984. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 44.Storz, G. 2002. An expanding universe of noncoding RNAs. Science 296:1260-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wassarman, K. M. 2002. Small RNAs in bacteria: diverse regulators of gene expression in response to environmental changes. Cell 109:141-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wassarman, K. M., F. Repoila, C. Rosenow, G. Storz, and S. Gottesman. 2001. Identification of novel small RNAs using comparative genomics and microarrays. Genes Dev. 15:1637-1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wassarman, K. M., and G. Storz. 2000. 6S RNA regulates E. coli RNA polymerase activity. Cell 101:613-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeiser, B., E. D. Pepper, M. F. Goodman, and S. E. Finkel. 2002. SOS-induced DNA polymerases enhance long-term survival and evolutionary fitness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:8737-8741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young, B. A., T. M. Gruber, and C. A. Gross. 2002. Views of transcription initiation. Cell 109:1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zambrano, M. M., and R. Kolter. 1993. Escherichia coli mutants lacking NADH dehydrogenase I have a competitive disadvantage in stationary phase. J. Bacteriol. 175:5642-5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zambrano, M. M., D. A. Siegele, M. Almiron, A. Tormo, and R. Kolter. 1993. Microbial competition: Escherichia coli mutants that take over stationary phase cultures. Science 259:1757-1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]