Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MS) and the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype (HW) in a representative adolescent sample; as well as to establish which anthropometric indicator better identifies MS and HW, according to gender and adolescent age.

METHODS:

This cross sectional study had the participation of 800 adolescents (414 girls) from 10-19 years old. Anthropometric indicators (body mass index, waist perimeter, waist/stature ratio, waist/hip ratio, and central/peripheral skinfolds) were determined by standard protocols. For diagnosis of MS, the criteria proposed by de Ferranti et al. (2004) were used. HW was defined by the simultaneous presence of increased waist perimeter (>75th percentile for age and sex) and high triglycerides (>100 mg/dL). The ability of anthropometric indicators was evaluated by Receiver Operating Characteristic curve.

RESULTS:

The prevalence of MS was identical to HW (6.4%), without differences between genders and the adolescence phases. The waist perimeter showed higher area under the curve for the diagnosis of MS, except for boys with 17-19 years old, for whom the waist/stature ratio exhibited better performance. For diagnosing HW, waist perimeter also showed higher area under the curve, except for boys in initial and final phases, in which the waist/stature ratio obtained larger area under the curve. The central/peripheral skinfolds had the lowest area under the curve for the presence of both MS and HW phenotype.

CONCLUSIONS:

The waist perimeter and the waist/stature showed a better performance to identify MS and HW in both genders and in all three phases of adolescence.

Keywords: Anthropometry, Adolescent, Abdominal obesity, Metabolic X syndrome, Hypertriglyceridemic waist

Introduction

Chronic, noncommunicable diseases are considered the leading cause of mortality in developed and developing countries,1 and their incidence rates are rapidly increasing, especially in developing countries.2 In Brazil, those diseases account for approximately 70% of mortality.3

Metabolic syndrome (MS) is defined as a group of alterations that includes central obesity, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and systemic arterial hypertension.4 The hypertriglyceridemic waist (HW) phenotype, one of the components of MS, is identified by the simultaneous presence of high waist circumference and high concentrations of triglycerides.5 Both phenotypes are important predictors of cardiovascular diseases,2 but the HW is considered a simpler method for screening individuals at increased cardiometabolic risk.6

The prevalence of MS and HW has been widely investigated in adults,4 , 5 , 7 - 10 but studies in children and adolescents are scarce.6 , 11 , 12 Studies carried out in Iran with children and adolescents aged 6-18 years reported a prevalence of 14.0% and 8.52% of MS and HW, respectively.6 , 13 Esmaillzadeh et al.11 observed MS prevalence of 10.1% in adolescents aged 10-19 years (10.3% in boys and 9.9% for girls) and 6.5% of HW (7.3% in boys and 5.6% in girls). Recently, a study observed HW prevalence of 7.2% in adolescents aged 11-17 years in Salvador city, state of Bahia, Brazil.12

Given the paucity of data on the HW phenotype in adolescents and the evidence that the prevalence of MS in children has been increasing,2 with a tendency to persist into adulthood,14 it becomes necessary to establish what is the best body fat distribution indicator for early identification of at-risk adolescents, aiming to establish interventions and improve future cardiovascular health.15 Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of MS and HW phenotype in a representative sample of adolescents and to establish which is the best anthropometric indicator to identify MS and the HW phenotype, according to gender and stage of adolescence.

Method

This is a cross-sectional study, which is part of a broader investigation carried out with adolescents aged 10-19 years, of both genders, from the rural and urban population of public and private schools (from the 5th year of Elementary School to the last year of High School) from the municipality of Viçosa, state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Sample size was calculated using the Epi Info software, release 6.04. Considering the population aged 10-19 years and 11 months living in the city according to the last census, in a total of 11,898 individuals,16 the expected prevalence is 50%, as the study considers as outcome multiple cardiovascular risk factors, 5% of acceptable variability, 99% confidence level and 20% increase to control for potential confounding factors; the sample calculation was estimated at 796 in adolescents. The value of 50% of prevalence was chosen because, when the information is not known, the most conservative method, which also maximizes sample size, is to adopt an estimate of 50%.

Inclusion criteria were: no regular use of drugs that altered blood glucose, insulinemia, lipid metabolism and/or blood pressure levels; no participation in weight reduction and control programs; no regular use of diuretics/laxatives, and not being pregnant or having been previously pregnant. Adolescents who met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study were separated by gender and grouped by age range (10-13 years: initial stage; 14-16 years: intermediate stage; 17-19 years: final stage).17

Students were selected among those who signed the informed consent form, by drawing a random sample, stratified by age group, from each school. When an individual refused to participate or withdraw the study, another student was selected to replace him/her. All participants and their parents/guardians in the case of adolescents younger than 18 years signed the informed consent form, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the rules of Resolution number 466/2012 of the National Health Council (CNS). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Universidade Federal de Viçosa (Of. Ref. number 0140/2010).

Data collection occurred between 7:00 am and 9:30 am at the Health Division of Federal University of Viçosa, by qualified and previously trained professionals.

Weight and height were measured using standardized international techniques, with adolescents barefoot and wearing light clothes,18 in an electronic digital scale (LC 200pp, Marte(r), São Paulo, Brazil) and a portable stadiometer (Alturexata(r), Belo Horizonte, Brazil). The body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the ratio between body weight (kg) and the height squared (m2).

Waist circumference was measured at midpoint between the lower margin of the lowest rib and the iliac crest, in the horizontal plane and at the end of a normal expiration. Hip circumference was measured on the gluteal region, over light clothes, and comprised the largest horizontal circumference between the waist and knees.18 All measurements were performed in duplicate by a single trained evaluator, accepting variations of 0.5cm and calculating the mean values, using a measuring tape with a length of 2 meters, flexible and inelastic (Cardiomed(r), São Luiz, MA, Brazil). Subsequently, the waist-to-height (WHtR) and waist-hip (WHR) ratios were calculated by dividing waist circumference (cm) by height (cm) and hip circumference (cm), respectively.

Subscapular, suprailiac, triceps and biceps skinfold thickness were measured on the right side of the body, and all measurements were taken three times, non-consecutively by a single trained evaluator using a Lange Skinfold Caliper (Cambridge Scientific, Cambridge, MA, USA), and the mean value was used.18 The peripheral skinfold was considered as the sum of the triceps and biceps folds, and the central skinfold as the sum of the subscapular and suprailiac folds, based on which the central/peripheral skinfold ratio was calculated.19

Blood samples were collected from the antecubital vein after 12-hour fasting, and serum was separated by centrifugation at 2,2253g for 15 minutes at room temperature (2-3 Sigma, Sigma Laborzentrifuzen, OsterodeamHarz, Germany). Blood glucose was measured by the glucose oxidase method using the Cobas Mira Plus equipment (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Montclair, NJ, USA). HDL and triglyceride levels were measured by the automated enzymatic colorimetric method in a Cobas Mira Plus equipment (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Montclair, NJ, USA) (Roche Corp.).

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure was measured, after a minimum 15-minute rest period, using automatic inflation blood pressure monitor (Omron(r) HEM-741 Model CINT, Kyoto, KYT, Japan) and a cuff size that was appropriate for the arm perimeter. The measurement was repeated twice in the arm with higher pressure value, with a 1-minute interval between them, and the mean of the last two measures was used.20

For the diagnosis of MS, the definition proposed by de Ferranti et al. was used,14 which is based on the presence of three of the following criteria: waist circumference >75th percentile for age and gender of the assessed population; HDL <50 mg/dL (except for boys aged 15-19, for whom a value <45 mg/dL was considered); triglycerides ≥100 mg/dL; systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure >90th percentile for gender, age and height, and fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL. It should be noted that the criterion of de Ferranti et al. proposes glycemia ≥110, but we chose to use the latest recommendations of the American Diabetes Association.21

The HW phenotype was defined according to the cutoffs used to define MS. The simultaneous presence of increased waist circumference (≥75th percentile for age and gender of the study population) and high levels of serum triglycerides (≥100 mg/dL) was considered HW.22

The database was created, and data were entered twice (double entry) using Microsoft Office Excel 2007, and the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, release 17.0, and MedCalc, release 9.3. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, graphical methods and asymmetry coefficient (skewness >1; asymmetric) were used to evaluate the variables for normality. Anthropometric, clinical and metabolic variables were compared between stages by ANOVA, followed by Tukey post hoc or Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Mann-Whitney with Bonferroni correction for variables with parametric and nonparametric distribution, respectively. For comparisons between genders, Student's t test or Mann-Whitney test was used for variables with parametric and non-parametric distribution, respectively. The occurrence of MS and HW, as well as their individual components, was compared between stages and between genders using Pearson's chi-square test. Additionally, receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were prepared, and the area under the curve was calculated in order to identify the best anthropometric indicator associated with MS and HW phenotype.

Results

All adolescents that attended public and private schools, both in urban and rural areas of the municipality of Viçosa/MG, were contacted in 2010. In the same year, the municipality had a total of 27 schools and all of them participated in the study. All adolescents who agreed to participate and gave their free and informed consent were included in this study a total of 828 adolescents. Of those, 28 were excluded for the following reasons: use of anticonvulsant medication (1); history of hypothyroidism (1); inadequate fasting (2); technical impossibility of collecting blood samples (1); use of antidepressants (fluoxetine) (9); history of myelomeningocele (1); presence of nasal cancer (1); growth hormone use (1); hormonal alterations (3); use of supplements and/or vitamins (5); previous pregnancy (2); swollen foot, with plaster (1). Thus, the studied adolescents consisted of 414 girls and 383 boys, with a mean age of 14.72 years (SD=2.95). Anthropometric, clinical and metabolic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the adolescents according to gender and stage of adolescence.

| Stage of adolescence | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Intermediary | Final | |||

| Girls | |||||

| N | 157 | 134 | 123 | 414 | |

| Age (years) | 11.57 (1.07)a | 15.67 (0.94)b | 18.17 (0.65)c | 14.86 (2.90)f | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.80 (3.37)a | 21.59 (3.99) | 21.19 (3.32)c | 20.41 (3.78)f | |

| WC (cm) | 68.82 (9.66)a | 76.22 (9.15) | 75.48 (9.10)c | 73.20 (9.92)f | |

| HC (cm) | 79.67 (9.17)a | 93.01 (9.02) | 92.88 (8.01)c | 87.91 (10.89)f | |

| WHR | 0.86 (0.05)a | 0.82 (0.05) | 0.81 (0.05)c | 0.83 (0.06)f | |

| WHtR | 0.46 (0.06) | 0.47 (0.06) | 0.47 (0.06) | 0.47 (0.06) | |

| CPR | 1.61 (0.59)a | 1.78 (0.44) | 1.86 (0.48)c | 1.74 (0.52)f | |

| Glycemia (mg/dL) | 86.08 (6.55)a | 82.49 (6.79) | 81.74 (5.93)c | 83.63 (6.73)f | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 52.56 (12.31) | 51.35 (11.75) | 51.86 (11.73) | 51.96 (11.94) | |

| TG (mg/dL) | 78.70 (37.24) | 71.38 (35.57) | 67.54 (31.27)c | 73.01 (35.25)f | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 95.59 (9.93)a | 99.61 (7.57) | 100.86 (8.30)c | 98.46 (9.02)f | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 60.61 (7.42) | 61.79 (6.75) | 63.48 (6.79)c | 61.85 (7.10)f | |

| Boys | |||||

| N | 179 | 95 | 112 | 386 | |

| Age (years) | 11.71 (1.13)a | 15.56 (0.89)b | 18.29 (0.83)c | 14.57 (3.01)f | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.34 (3.73)a | 20.88 (3.32)b | 22.25 (3.85)c | 20.10 (4.04)f | |

| WC (cm) | 67.10 (10.61)a | 74.47 (9.27) | 77.79 (9.96)c | 72.02 (11.14)f | |

| HC (cm) | 75.72 (9.73)a | 89.40 (8.71)b | 92.77 (9.22)c | 84.04 (12.18)f | |

| WHR | 0.88 (0.04)a | 0.83 (0.05) | 0.84 (0.04)c | 0.86 (0.05)f | |

| WHtR | 0.45 (0.06) | 0.44 (0.05) | 0.45 (0.05) | 0.45 (0.06) | |

| CPR | 1.34 (0.47)a | 1.67 (0.49)b | 1.94 (0.54)c | 1.59 (0.56)f | |

| Glycemia (mg/dL) | 86.74 (6.56) | 86.68 (6.23)b | 83.74 (6.73)c | 85.86 (6.65)f | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 51.31 (13.72)a | 46.77 (11.01) | 46.42 (10.48)c | 48.77 (12.41)f | |

| TG (mg/dL) | 69.54 (33.53) | 66.56 (38.55) | 66.88 (31.30) | 68.03 (34.16) | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 96.17 (10.33)a | 103.98 (10.50)b | 110.21 (8.56)c | 102.17 (11.57)f | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 58.18 (6.85) | 58.66 (7.92) | 59.75 (8.08) | 58.76 (7.50) | |

| Total | |||||

| N | 336 | 229 | 235 | 800 | |

| Age (years) | 11.64 (1.10)a | 15.63 (0.92)b | 18.22 (0.74)c,e | 14.72 (2.95)e,f | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.55 (3.57)a | 21.30 (3.74) | 21.69 (3.61)c | 20.26 (3.91)f | |

| WC (cm) | 67.91 (10.20)a | 75.50 (9.22) | 76.58 (9.56)c | 72.63 (10.53)f | |

| HC (cm) | 77.57 (9.66)a | 91.52 (9.05) | 92.83 (8.59)c | 86.04 (11.68)e,f | |

| WHR | 0.87 (0.05)a,e | 0.82 (0.05) | 0.82 (0.05)c | 0.84 (0.05)e,f | |

| WHtR | 0.45 (0.06) | 0.46 (0.06) | 0.46 (0.06) | 0.46 (0.06)e | |

| CPR | 1.46 (0.54)a,e | 1.74 (0.46)b | 1.90 (0.51)c | 1.67 (0.56)e,f | |

| Glycemia (mg/dL) | 86.43 (6.55)a | 84.23 (6.87)b | 82.69 (6.39)c,d | 84.70 (6.77)e,f | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 51.90 (13.08) | 49.45 (11.65) | 49.27 (11.46)c | 50.42 (12.26)e,f | |

| TG (mg/dL) | 73.82 (35.55) | 69.38 (36.83) | 67.23 (31.21) | 70.61 (34.79) | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 95.90 (10.13)a | 101.42 (9.14)b,e | 105.32 (9.63)c | 100.25 (10.48)e,f | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 59.32 (7.21) | 60.49 (7.40) | 61.70 (7.65)c | 60.35 (7.45)e,f | |

Data shown as mean (standard deviation). BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; HC, hip circumference; WHR, waist-hip ratio; WHtR, waist-height ratio; CPR, central/peripheral skinfold ratio; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; TG, triglycerides; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

Differences between the initial and intermediary stages.

Differences between intermediary and final stages.

Differences between initial and final stages.

p<0.05 between genders.

p<0.01 between genders.

f p<0.01 between stages.

Girls had higher hip circumference values, waist/height ratio, central/peripheral skinfold ratio, HDL, and diastolic blood pressure when compared to boys. Boys had higher blood glucose and systolic blood pressure levels. The parameters body mass index, waist circumference, triglycerides and age did not differ between the genders. Some variables did not change with age, namely the waist/height ratio and HDL in girls and waist/height ratio, triglycerides and diastolic blood pressure in boys. When comparing the stages of adolescence, it was observed that, in females, the intermediate and final stages did not differ between each other (early stage<intermediate stage=final stage), whereas in boys, the parameters usually differed between the stages (initial stage<intermediate stage<final stage, except for glucose levels, which decreased from the intermediate to the final stage).

Table 2 discloses the presence of MS, HW phenotype and their components, according to the gender and adolescence stage. The prevalence of MS was identical to that of HW (6.4%), with no differences between genders and between the stages of adolescence. Among the MS components, the most prevalent was low HDL. Regarding phenotype, the prevalence of abdominal obesity was higher than that of hypertriglyceridemia. The prevalence of high blood pressure was higher in boys (p<0.01), while hypertriglyceridemia was more prevalent in girls (p<0.01).

Table 2. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome, hypertriglyceridemic waist and individual components according to gender and stage of adolescence.

| Stage | Waist ≥P75 | Elevated TG | Low HDL | Elevated glycemia | Elevated BP | MS | HW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Girls | |||||||

| Initial (n=157) | 38 (24.2) | 35 (22.3) | 70 (44.6) | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.5) | 15 (9.5) | 11 (7.0) |

| Intermediary (n=134) | 34 (25.4) | 22 (16.4) | 64 (47.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.5) | 7 (5.2) | 9 (6.7) |

| Final (n=123) | 31 (25.2) | 16 (13.0) | 50 (40.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 5 (4.1) | 6 (4.9) |

| Total (n=414) | 103 (24.9) | 73 (17.6)a | 184 (44.4) | 3 (0.7) | 7 (1.7)a | 27 (6.5) | 26 (6.3) |

| Boys | |||||||

| Initial (n=179) | 134 (25.1) | 22 (12.3) | 88 (49.2) | 1 (0.6) | 6 (3.4) | 14 (7.8) | 12 (6.7) |

| Intermediary (n=95) | 24 (25.3) | 10 (10.5) | 45 (47.4) | 1 (1.0) | 6 (6.3) | 4 (4.2) | 5 (5.3) |

| Final (n=112) | 29 (25.9) | 13 (11.6) | 49 (43.8) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (3.6) | 6 (5.4) | 8 (7.1) |

| Total (n=386) | 98 (25.4) | 45 (11.7)a | 182 (47.2) | 3 (0.8) | 16 (4.2)a | 24 (6.2) | 25 (6.5) |

| Total | |||||||

| Initial (n=336) | 83 (24.7) | 57 (16.9) | 158 (47.0) | 4 (1.2) | 10 (2.9) | 29 (8.6) | 23 (6.9) |

| Intermediary (n=229) | 58 (25.3) | 32 (13.9) | 109 (47.6) | 1 (0.4) | 8 (3.5) | 11 (4.8) | 14 (6.1) |

| Final (n=235) | 60 (25.5) | 29 (12.3) | 99 (42.1) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (2.1) | 11 (4.7) | 14 (5.9) |

| Total (n=800) | 201 (25.1) | 118 (14.8) | 366 (45.8) | 6 (0.8) | 23 (2.9) | 51 (6.4) | 51 (6.4) |

MS, metabolic syndrome; HW, hypertriglyceridemic waist; P, percentile; TG, triglycerides; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; BP, blood pressure.

p<0.01 between genders.

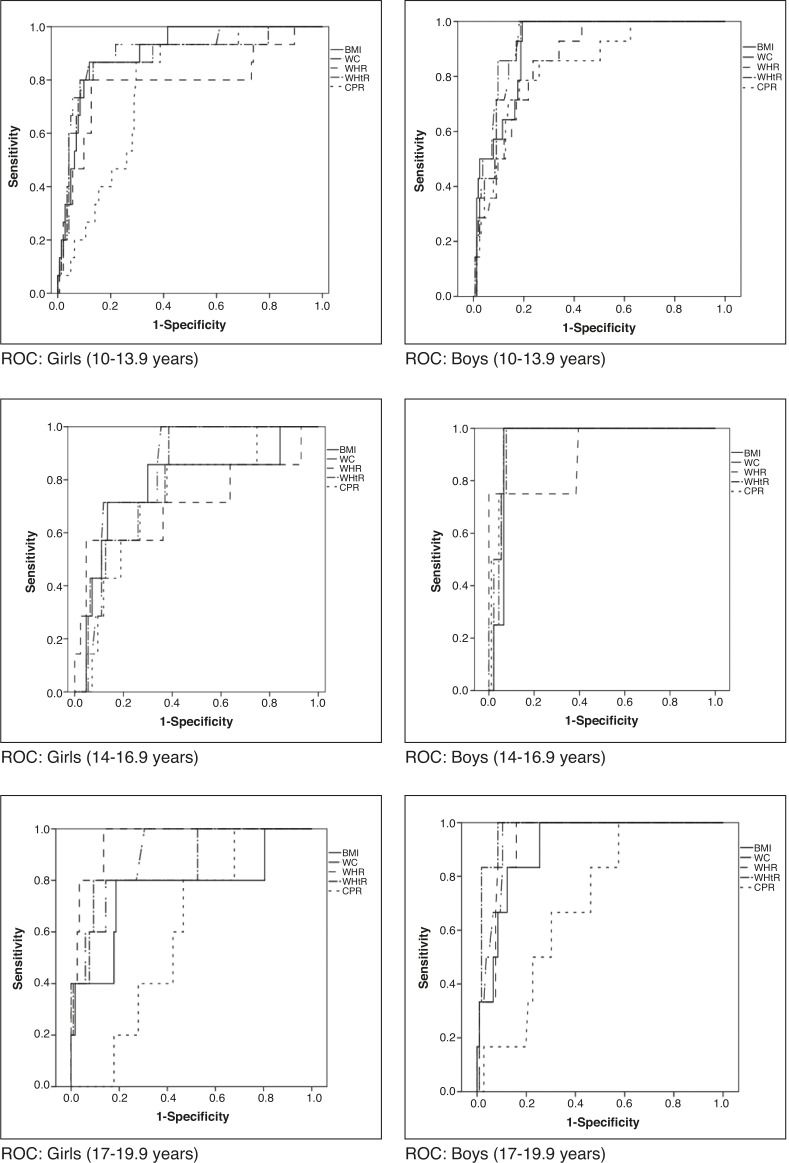

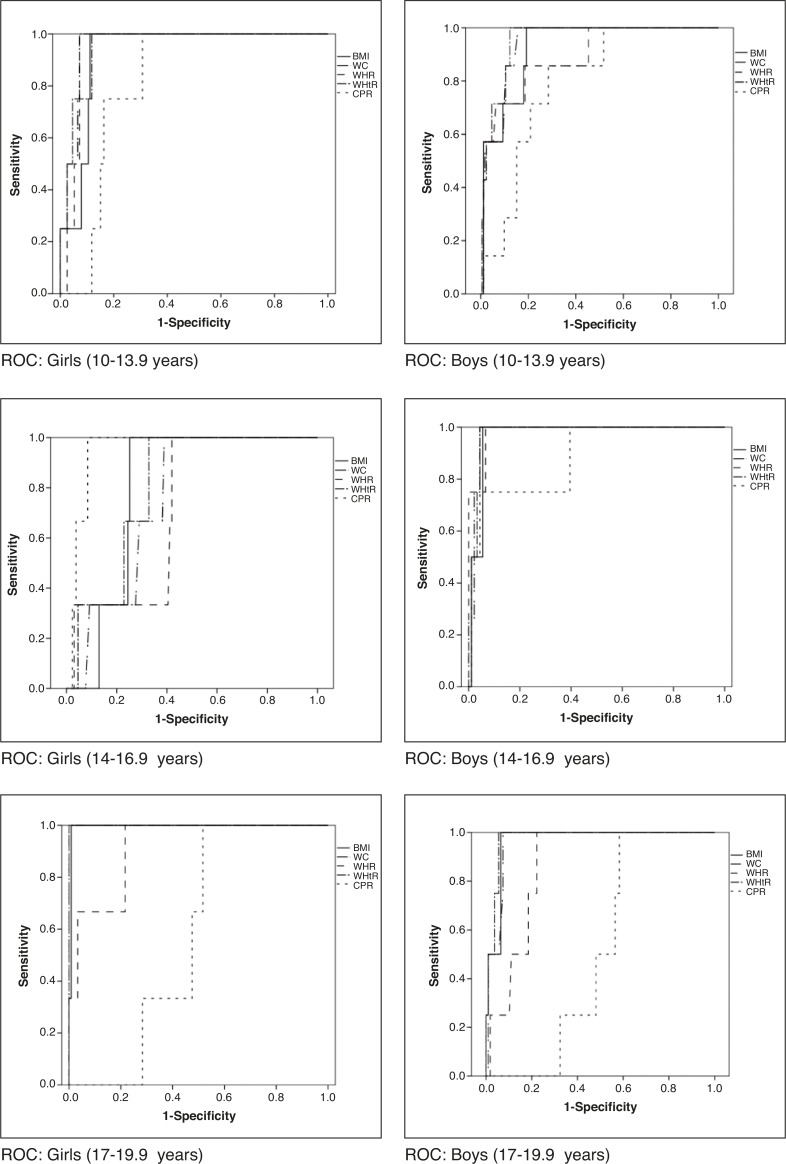

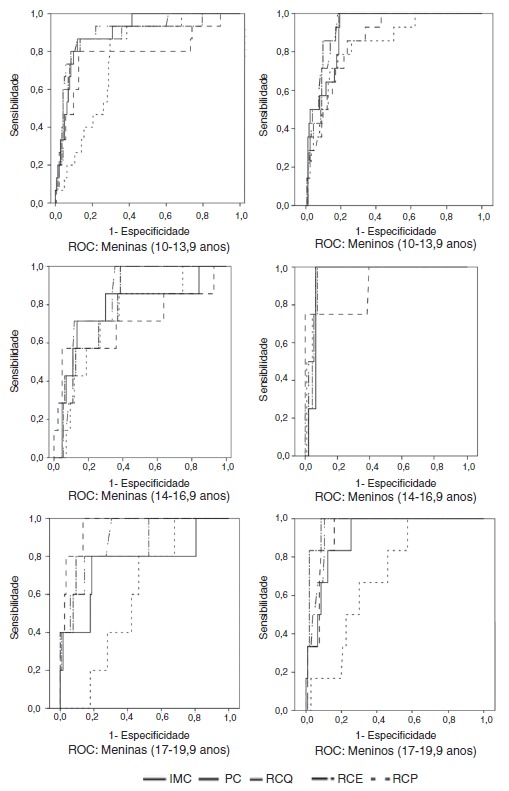

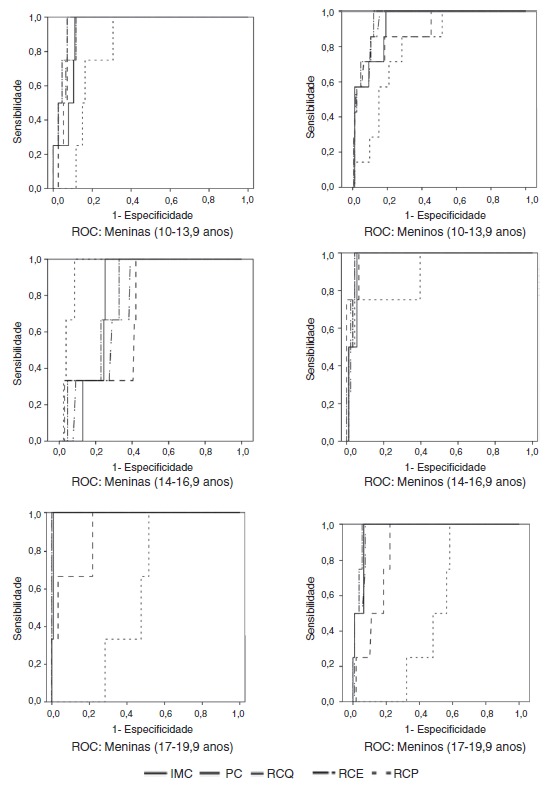

When assessing which anthropometric indicator showed better performance in the prediction of MS and HW, waist circumference showed the highest absolute values of area under the curve in all analyses, except for boys in the initial and final stages in the diagnosis of HW and for boys in the final stage in the diagnosis of MS, in whom the waist-to-height ratio showed higher absolute value of area under the curve. In turn, the central/peripheral skinfold ratio showed the smallest areas under the curve for the presence of both MS and HW (Table 3). The areas under the curves were calculated using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (Figs. 1 and 2).

Table 3. Areas under the curve (95%CI) of anthropometric indicators as predictors of metabolic syndrome and hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype.

| Gender | Stage | BMI | WC | WHR | WHtR | CPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | ||||||

| Girls | Initial | 0.906 (0.849; 0.946)b |

0.906 (0.849; 0.946)b |

0.789 (0.717; 0.850)b |

0.881 (0.819; 0.927)b |

0.767 (0.693; 0.831)b |

| Intermediary | 0.778 (0.699; 0.846)a |

0.835 (0.761; 0.894)b | 0.706 (0.622; 0.782) | 0.818 (0.742; 0.879)b | 0.733 (0.650; 0.806)a |

|

| Final | 0.763 (0.678; 0.835)a |

0.902 (0.835; 0.948)b |

0.961 (0.910; 0.987)b |

0.864 (0.790; 0.919)b |

0.595 (0.503; 0.682) |

|

| Boys | Initial | 0.914 (0.863; 0.951)b |

0.929 (0.881; 0.962)b |

0.861 (0.802; 0.908)b |

0.924 (0.875; 0.958)b |

0.839 (0.777; 0.890)b |

| Intermediary | 0.945 (0.878; 0.981)b |

0.964 (0.904; 0.991)b |

0.902 (0.824; 0.954)b |

0.953 (0.889; 0.986)b |

0.967 (0.908; 0.992)b |

|

| Final | 0.910 (0.841; 0.956)b |

0.948 (0.889; 0.981)b |

0.931 (0.867; 0.970)b |

0.976 (0.928; 0.995)b |

0.700 (0.607; 0.783) |

|

| HW | ||||||

| Girls | Initial | 0.926 (0.874; 0.962)a |

0.959 (0.915; 0.984)a |

0.944 (0.896; 0.975)a |

0.954 (0.909; 0.981)a |

0.815 (0.746; 0.873)a |

| Intermediary | 0.872 (0.815; 0.929) |

0.917 (0.870; 0.965) |

0.955 (0.920; 0.990) |

0.970 (0.941; 0.999) |

0.902 (0.852; 0.953) |

|

| Final | 0.994 (0.960; 0.998)b |

1.000 (0.970; 1.000)b |

0.917 (0.853; 0.959)b |

0.999 (0.967; 1.000)a |

0.575 (0.483; 0.664) |

|

| Boys | Initial | 0.927 (0.878; 0.960)b |

0.943 (0.898; 0.972)b |

0.894 (0.839; 0.935)b |

0.953 (0.911; 0.979)b |

0.797 (0.730; 0.853)b |

| Intermediary | 0.967 (0.908; 0.992)b |

0.978 (0.924; 0.997)b |

0.984 (0.933; 0.998)b |

0.977 (0.922; 0.996)b |

0.885 (0.803; 0.941)b |

|

| Final | 0.965 (0.912; 0.990)b |

0.961 (0.906; 0.988)b |

0.867 (0.790; 0.924)b |

0.977 (0.929; 0.996)a |

0.512 (0.415; 0.607) |

|

CI, confidence interval; MS, metabolic syndrome; HW, hypertriglyceridemic waist; BMI, body mass index (kg/m2); WC, waist circumference (cm); WHR, waist/hip ratio; WHtR, waist/height ratio; CPR, central/peripheral skinfold ratio.

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

Figure 1. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for metabolic syndrome according to gender and stage of adolescence. BMI, body mass index (kg/m2); WC, waist circumference (cm); WHR, waist/hip ratio; WHtR, waist/height ratio; CPR, central/peripheral skinfold ratio.

Figure 2. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype according to gender and stage of adolescence. BMI, body mass index (kg/m2); WC, waist circumference (cm); WHR, waist/hip ratio; WHtR, waist/height ratio; CPR, central/peripheral skinfold ratio.

Discussion

The present study, carried out with adolescents in a representative sample of rural and urban, public and private school populations from Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil, identified a prevalence rate of 6.4% for MS and HW phenotype, with no differences between genders and adolescence stages.

MS is a health problem in the pediatric group in developed countries and especially in developing ones2; however, as yet there is no formal, unified criterion for its diagnosis in children and adolescents, and the use of different criteria for this definition has been observed in different populations, making it difficult to compare prevalence.13 The prevalence of MS in the United States, according to the same criteria used in this study, was estimated at 12.9% in Mexican-Americans, 10.9% among non-Hispanic whites, and 2.5% for non-Hispanic blacks.14 Kelishadi et al.13 observed a prevalence of 14% (13% for girls and 14% for boys) of MS using similar criteria to those of the present study. In Brazil, a study of children and adolescents in Salvador, state of Bahia, observed the prevalence of 6.6% (8.5% in girls and 4.7% in boys).23

The prevalence of HW phenotype in this study (6.4%) was similar to that observed in a study with adolescents aged 10-19 years in Tehran (Iran) (6.4%),11 and similar to that identified in children and adolescents aged 6-18 years from Iran (8.5%),6 in adolescents aged 10-19 years from the UK (7.3%),22 and in adolescents aged 11-17 years from Salvador/Bahia, Brazil (7.2%).12 However, a study carried out in England24 with obese children and adolescents aged 8-18 years found a prevalence of 40% of HW phenotype.22 Differences in MS and HW phenotype prevalence can be attributed to variations in the cutoffs used to classify central obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and other components of MS between different studies and their differences regarding nutritional status, sexual maturation, race/ethnicity and life habits between regions.12 , 25

Among the components of MS, low HDL concentrations were the most prevalent, which can be explained by the current nutritional transition process experienced in Brazil, where food consumption consists mainly of high-energy food and, among adolescents, one can observe a high frequency of consumption of cookies, sausages, hotdogs, bologna, sandwiches and salty snacks. The prevalence of inadequate intake of saturated fat was greater than 80%, and the consumption of cream-filled cookies, which contain hydrogenated fats and trans-fatty acids, was four times higher in this group compared to adults.26 Low levels of physical activity commonly observed in this age group constitute another factor that possibly contributes to the high prevalence of low HDL levels.27

In this sense, although the experience of using the HW phenotype as a diagnostic tool for cardiometabolic risk in adolescents is still limited, it has been documented that in adults, this phenotype is capable of identifying individuals with the atherogenic triad, comprising increased concentrations of small and dense LDL, apolipoprotein B and hyperinsulinemia, and who are at high risk for cardiovascular disease.5 In a longitudinal study with adults in Tehran (n=6,834) the HW phenotype increased the risk of cardiovascular disease incidence.9 The results of the present study suggest that these two measures, WC and triglycerides, can be used to substitute higher-cost indicators to identify adolescents at risk of metabolic disorders.

The second objective of this study was to determine which anthropometric index performs best to identify the occurrence of MS and HW phenotype. The ROC analyses demonstrated that WC and waist/height ratio had a higher area under the curve to identify both MS and HW. Studies have shown that the WC in adolescents is a good indicator of visceral abdominal fat content28 and cardiovascular risk factors,13 , 29 , 30 and it can be a simple tool to identify MS in children and adolescents.13 , 23 , 25 In a study carried out in children and adolescents (8-18 years), waist/height ratio showed to be a slightly better predictor of MS (area under the curve=0.83 [0.78 to 0.89]) than WC (area under the curve=0.79 [0.73 to 0.85]) and BMI (area under the curve=0.79 [0.72 to 0.85]).23 One of the advantages of waist/height ratio is the possibility of using the cutoff ≥0.5, which is applicable to both genders and all ages, to identify children and adolescents at cardiovascular risk.15 Body mass index, an indicator widely used in pediatric clinical practice for the assessment of nutritional status, showed a worse performance than waist circumference and waist/height ratio, which is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the superiority of waist circumference as an isolated measure or adjusted by height.13 , 25 , 28 Additionally, waist circumference is less affected than body mass index by gender, ethnicity, and total fat.28

The index with the worst performance was the central/peripheral skinfold ratio, which can be explained by the fact that skinfolds estimate subcutaneous and not visceral fat, and the latter is the one associated with increased risk.31 Moreover, the validity of indicators that are based on the association between two or more measures, compared to individual measures, to predict cardiovascular risk has been questioned.32

This study has some limitations, such as the cross-sectional design, which does not allow the assessment of the precise effects of growth on waist measurement, and ethnicity, which is one of the factors that affect body fat distribution. However, the effects of the latter were not assessed, as the classification could be inaccurate due to the great multi-ethnicity of the Brazilian population. Another limitation was the impossibility to assess the stage of sexual maturation of the participants. Despite of puberty effects on body fat distribution, we attempted to control them by employing specific WC cutoffs for age and gender. Finally, lifestyle characteristics (food and physical activity habits) could affect the association between the occurrence of obesity and other associated metabolic disorders; therefore they should be included in further studies.

It can be concluded that, according to the study results, HW phenotype is a simple tool to substitute MS in screening individuals at cardiometabolic risk. Regarding the capacity of the anthropometric indicators, waist circumference and waist/height ratio showed better performance to identify MS and HW, two major phenotypes of cardiometabolic risk in both genders and at all stages of adolescence, which emphasizes the importance of incorporating the measurement of these parameters in pediatric clinical routine.

These observations lead to the demand for a national waist circumference reference curve for adolescents, which could be used both in the clinical setting and in population surveillance to identify young, but at high risk, asymptomatic individuals who might benefit from an early intervention. It is believed that such iniciatives could impact on primary prevention in public health.

Funding Statement

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (number 485986/2011-6) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (APQ-00872-12).

Footnotes

Funding Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (number 485986/2011-6) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (APQ-00872-12).

References

- 1.World Health Organization [página na Internet]. World Health Statistics [acessado em 12 de agosto de 2014]. Disponível em: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/en/; World Health Organization World Health Statistics. [12 de agosto de 2014]. a Disponível em: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/en/

- 2.Kelishadi R. Childhood overweight, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:62-76. [DOI] [PubMed]; Kelishadi R. Childhood overweight, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:62–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Análise de Situação de Saúde. In: Plano de ações estratégicas para o enfrentamento das doenças crônicas não transmissíveis (DCNT) no Brasil 2011-2022. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2011.; Brasil . Plano de ações estratégicas para o enfrentamento das doenças crônicas não transmissíveis (DCNT) no Brasil 2011-2022. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2011. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Análise de Situação de Saúde. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640-5. [DOI] [PubMed]; Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemieux I, Pascot A, Couillard C, Lamarche B, Tchernof A, Alméras N, et al. Hypertriglyceridemic waist: a marker of the atherogenic metabolic triad (hyperinsulinemia; hyperapolipoprotein B; small, dense LDL) in Men? Circulation. 2000;102:179-84. [DOI] [PubMed]; Lemieux I, Pascot A, Couillard C, Lamarche B, Tchernof A, Alméras N. Hypertriglyceridemic waist: a marker of the atherogenic metabolic triad (hyperinsulinemia; hyperapolipoprotein B; small, dense LDL) in Men? Circulation. 2000;102:179–184. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alavian SM, Motlagh ME, Ardalan G, Motaghian M, Davarpanah AH, Kelishadi R. Hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype and associated lifestyle factors in a national population of youths: Caspian Study. J Trop Pediatr. 2008;54:169-77. [DOI] [PubMed]; Alavian SM, Motlagh ME, Ardalan G, Motaghian M, Davarpanah AH, Kelishadi R. Hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype and associated lifestyle factors in a national population of youths: Caspian Study. J Trop Pediatr. 2008;54:169–177. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmm105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogowski O, Shapira I, Steinvil A, Berliner S. Low-grade inflammation in individuals with the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype: another feature of the atherogenic dysmetabolism. Metabolism. 2009;58:661-7. [DOI] [PubMed]; Rogowski O, Shapira I, Steinvil A, Berliner S. Low-grade inflammation in individuals with the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype: another feature of the atherogenic dysmetabolism. Metabolism. 2009;58:661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radenkovi´c SP, Koci´c RD, Pe?si´c MM, Dimi´c DN, Golubovi´c MD, Radojkovi´c DB, et al. The hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype and metabolic syndrome by differing criteria in type 2 diabetic patients and their relation to lipids and blood glucose control. Endokrinol Pol. 2011;62:316-23. [PubMed]; Radenkovi´c SP, Koci´c RD, Pe?si´c MM, Dimi´c DN, Golubovi´c MD, Radojkovi´c DB. The hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype and metabolic syndrome by differing criteria in type 2 diabetic patients and their relation to lipids and blood glucose control. Endokrinol Pol. 2011;62:316–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samadi S, Bozorgmanesh M, Khalili D, Momenan A, Sheikholeslami F, Azizi F, et al. Hypertriglyceridemic waist: the point of divergence for prediction of CVD vs. mortality: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;165:260-5. [DOI] [PubMed]; Samadi S, Bozorgmanesh M, Khalili D, Momenan A, Sheikholeslami F, Azizi F. Hypertriglyceridemic waist: the point of divergence for prediction of CVD vs. mortality: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;165:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Chen S, Shao X, Guo J, Liu X, Liu A, et al. Association of uric acid with metabolic syndrome in men, premenopausal women and postmenopausal women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:2899-910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Li Y, Chen S, Shao X, Guo J, Liu X, Liu A. Association of uric acid with metabolic syndrome in men, premenopausal women and postmenopausal women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:2899–2910. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110302899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esmaillzadeh A, Mirmiran P, Azadbakht L, Azizi F. Prevalence of the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype in Iranian adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:52-8. [DOI] [PubMed]; Esmaillzadeh A, Mirmiran P, Azadbakht L, Azizi F. Prevalence of the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype in Iranian adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conceição-Machado ME, Silva LR, Santana ML, Pinto EJ, Silva Rde C, Moraes LT, et al. Hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype: association with metabolic abnormalities in adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013;89:56-63. [DOI] [PubMed]; Conceição-Machado ME, Silva LR, Santana ML, Pinto EJ, Silva Rde C, Moraes LT. Hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype: association with metabolic abnormalities in adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2013;89:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelishadi R, Ardalan G, Gheiratmand R, Adeli K, Delavari A, Majdzadeh R, et al. Paediatric metabolic syndrome and associated anthropometric indices: the Caspian study. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:1625-34. [DOI] [PubMed]; Kelishadi R, Ardalan G, Gheiratmand R, Adeli K, Delavari A, Majdzadeh R. Paediatric metabolic syndrome and associated anthropometric indices: the Caspian study. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:1625–1634. doi: 10.1080/08035250600750072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Ferranti SD, Gauvreau K, Ludwig DS, Neufeld EJ, Newburger JW, Rifai N. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in American adolescents: findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Circulation. 2004;110:2494-7. [DOI] [PubMed]; De Ferranti SD, Gauvreau K, Ludwig DS, Neufeld EJ, Newburger JW, Rifai N. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in American adolescents: findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Circulation. 2004;110:2494–2497. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145117.40114.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy HD. Measuring growth and obesity across childhood and adolescence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2014;73:210-7. [DOI] [PubMed]; McCarthy HD. Measuring growth and obesity across childhood and adolescence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2014;73:210–217. doi: 10.1017/S0029665113003868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brasil Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística& #091;página na Internet]. Censo demográfico 2010 [acessado em 12 de agosto de 2014]. Disponível em: http://www.cidades.ibge.gov.br; Brasil-Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística Censo demográfico 2010. 2010. [12 de agosto de 2014]. a Disponível em: http://www.cidades.ibge.gov.br.

- 17.World Health Organization [página na Internet]. Nutrition in adolescence issues and challenges for the health sector: issues in adolescent health and development [acessado em 12 de agosto de 2014]. Disponível em http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241593660eng.pdf; World Health Organization Nutrition in adolescence issues and challenges for the health sector: issues in adolescent health and development. [12 de agosto de 2014]. a Disponível em http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241593660eng.pdf.

- 18.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 1988.; Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wärnberg J, Nova E, Moreno LA, Romeo J, Mesana MI, Ruiz JR, et al. Inflammatory proteins are related to total and abdominal adiposity in a healthy adolescent population: the Avena study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:505-12. [DOI] [PubMed]; Wärnberg J, Nova E, Moreno LA, Romeo J, Mesana MI, Ruiz JR. Inflammatory proteins are related to total and abdominal adiposity in a healthy adolescent population: the Avena study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:505–512. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia; Sociedade Brasileira de Hipertensão; Sociedade Brasileira de Nefrologia. VI Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão Arterial. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;95 Suppl 1:1-51. [PubMed]; Sociedade Brasileira de CardiologiaSociedade Brasileira de HipertensãoSociedade Brasileira de Nefrologia VI Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão Arterial. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;95(1):1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;35 Suppl 1:S43-8. [PubMed]; American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;35(1):S43–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobkirk JP, King RF, Gately P, Pemberton P, Smith A, Barth JH, et al. The predictive ability of triglycerides and waist (hypertriglyceridemic waist) in assessing metabolic triad change in obese children and adolescents. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2013;11:336-42. [DOI] [PubMed]; Hobkirk JP, King RF, Gately P, Pemberton P, Smith A, Barth JH. The predictive ability of triglycerides and waist (hypertriglyceridemic waist) in assessing metabolic triad change in obese children and adolescents. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2013;11:336–342. doi: 10.1089/met.2012.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribeiro-Silva RC, Florence TC, Conceição-Machado ME, Fernandes GB, Couto RD. Anthropometric indicators for prediction of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: a population-based study. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant. 2014;14:173-81.; Ribeiro-Silva RC, Florence TC, Conceição-Machado ME, Fernandes GB, Couto RD. Anthropometric indicators for prediction of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: a population-based study. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant. 2014;14:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey DP, Savory LA, Denton SJ, Davies BR, Kerr CJ. The hypertriglyceridemic waist, waist-to-height ratio, and cardiometabolic risk. J Pediatr. 2013;162:746-52. [DOI] [PubMed]; Bailey DP, Savory LA, Denton SJ, Davies BR, Kerr CJ. The hypertriglyceridemic waist, waist-to-height ratio, and cardiometabolic risk. J Pediatr. 2013;162:746–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereira PF. Medidas de localização da gordura corporal e fatores de risco para doenças cardiovasculares em adolescentes do sexo feminino Viçosa-MG. Viçosa: UFV; 2008. Tese de mestrado.; Pereira PF. Medidas de localização da gordura corporal e fatores de risco para doenças cardiovasculares em adolescentes do sexo feminino Viçosa-MG. Viçosa: UFV; 2008. Tese de mestrado. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brasil Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Diretoria de Pesquisas. Coordenação de Trabalho e Rendimento. In: Pesquisa de orçamentos familiares 2008-2009: análise do consumo alimentar pessoal no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2011.; Brasil Ministério do Planejamento.Orçamento e Gestão . Pesquisa de orçamentos familiares 2008-2009: análise do consumo alimentar pessoal no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2011. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Diretoria de Pesquisas. Coordenação de Trabalho e Rendimento. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandes RA, Christofaro DG, Milanez VF, Casonatto J, Cardoso JR, Ronque ER, et al. Physical activity: rate, related factors, and association between parents and children. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2011;29:54-9.; Fernandes RA, Christofaro DG, Milanez VF, Casonatto J, Cardoso JR, Ronque ER. Physical activity: rate, related factors, and association between parents and children. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2011;29:54–59. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daniels SR, Khoury PR, Morrison JA. Utility of different measures of body fat distribution in children and adolescents. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:1179-84. [DOI] [PubMed]; Daniels SR, Khoury PR, Morrison JA. Utility of different measures of body fat distribution in children and adolescents. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:1179–1184. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.12.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrington DM, Staiano AE, Broyles ST, Gupta AK, Katzmarzyk PT. Waist circumference measurement site does not affect relationships with visceral adiposity and cardiometabolic risk factors in children. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8:199-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Harrington DM, Staiano AE, Broyles ST, Gupta AK, Katzmarzyk PT. Waist circumference measurement site does not affect relationships with visceral adiposity and cardiometabolic risk factors in children. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8:199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pereira PF, Serrano HM, Carvalho GQ, Lamounier JA, Peluzio MC, Franceschini SC, et al. Waist and waist-to-height ratio: useful to identify the metabolic risk of female adolescents? Rev Paul Pediatr. 2011;29:372-7.; Pereira PF, Serrano HM, Carvalho GQ, Lamounier JA, Peluzio MC, Franceschini SC. Waist and waist-to-height ratio: useful to identify the metabolic risk of female adolescents? Rev Paul Pediatr. 2011;29:372–377. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orphanidou C, McCargar L, Birmingham CL, Mathieson J, Goldner E. Accuracy of subcutaneous fat measurement: comparison of skinfold calipers, ultrasound, and computed tomography. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94:855-8. [DOI] [PubMed]; Orphanidou C, McCargar L, Birmingham CL, Mathieson J, Goldner E. Accuracy of subcutaneous fat measurement: comparison of skinfold calipers, ultrasound, and computed tomography. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94:855–858. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)92363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sangi H, Muller WH. Which measure of body fat distribution is best for epidemiologic research among adolescents? Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:870-83. [DOI] [PubMed]; Sangi H, Muller WH. Which measure of body fat distribution is best for epidemiologic research among adolescents. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:870–883. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]