Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate the association between calcium intake and serum vitamin D levels and childhood obesity by an integrative review.

DATA SOURCE:

The research was conducted in the databases PubMed/medLine, Science Direct and SciELO with 2001 to 2014 publications. We used the combined terms in English: ''children'' and ''calcium'' or ''children'' and ''vitamin D'' associated with the descriptors: ''obesity'', ''adiposity'' or ''body fat'' for all bases. Cross-sectional and cohort studies, as well as clinical trials, were included. Review articles or those that that have not addressed the association of interest were excluded.

DATA SYNTHESIS:

Eight articles were part of this review, five of which were related to calcium and three to vitamin D. Most studies had a longitudinal design. The analyzed studies found an association between calcium intake and obesity, especially when age and sex were considered. Inverse relationship between serum vitamin D and measures of adiposity in children has been observed and this association was influenced by the sex of the patient and by the seasons of the year.

CONCLUSIONS:

The studies reviewed showed an association between calcium and vitamin D with childhood obesity. Considering the possible protective effect of these micronutrients in relation to childhood obesity, preventive public health actions should be designed, with emphasis on nutritional education.

Keywords: Children, Calcium, Vitamin D, Obesity, Adiposity

Introduction

Obesity is considered a public health problem that has been increasingly reaching alarming proportions in all regions of the world.1 - 3 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the worldwide prevalence of obesity has nearly doubled since 1980.3

Childhood obesity prevention is a high priority3 and is associated with dietary habits and practice of physical activity. However, it is known that other factors may determine childhood obesity, regardless of caloric intake, such as nutrigenomics, prenatal nutrition and breastfeeding, the intestinal microbiota health, the consumption of foods with functional properties and the ingestion of omega-3, zinc, vitamins A, C, D, E, folate and calcium4 and these factors may contribute for the prevention and auxiliary treatment of this disease.

The deficiency of micronutrients, such as calcium and vitamin D, is common in many countries, regardless of the nutritional status; however, its magnitude is greater in children with excess weight.2 , 5 - 7 In this context, concerns about the association between calcium intake and serum vitamin D and metabolic diseases in children has gained prominence in the scientific world for at least 30 years,8 and several studies have attempted to clarify the several questions about the subject,6 , 9 , 10 as the combination of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25 [OH] D) and inadequate calcium intake has been associated with cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, obesity, metabolic syndrome (MS) and type 2 diabetes mellitus.2 , 4 , 5 , 8 That is, the combined deficiency of both nutrients deserve special consideration in children.4

However, the recommendations of calcium and vitamin D intake have not been proposed for the prevention of noncommunicable chronic diseases, as the studies are still scarce, inconsistent and sometimes of poor quality.11 Although vitamin D insufficiency and low calcium intake are commonly reported, little is known about the effect of these micronutrients in the prevention and treatment of diseases such as obesity. Given the above, this integrative review aimed to evaluate the association between calcium intake and serum vitamin D levels with body fat (BF) accumulation in children.

Method

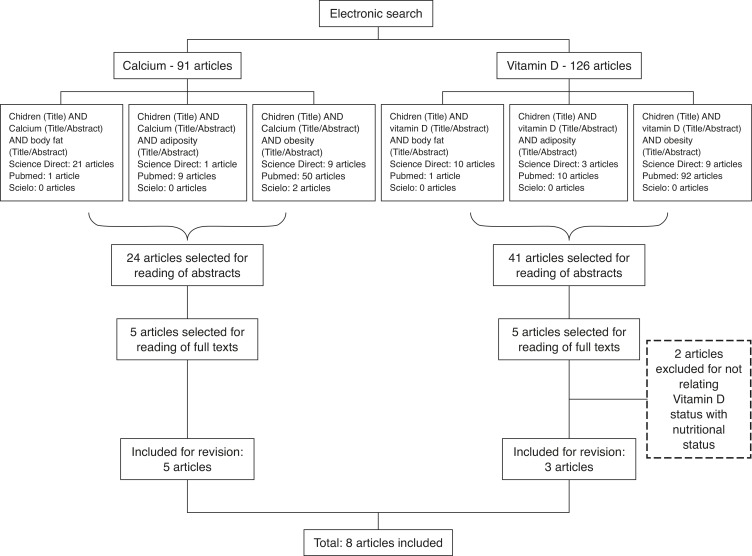

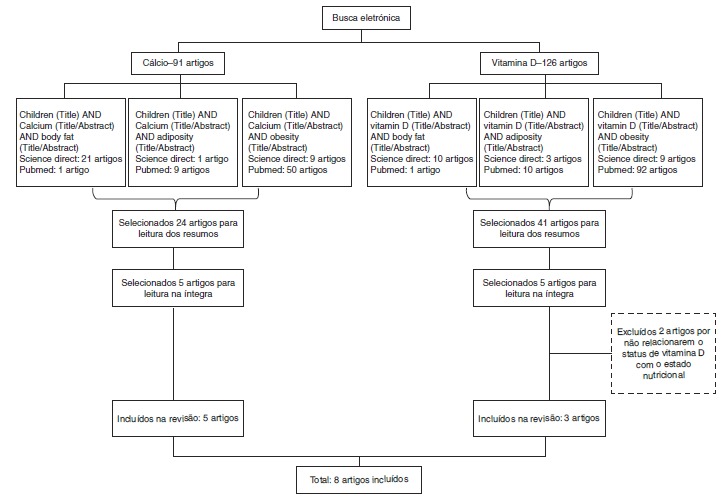

The survey was carried out by searching the PUBMED, Science Direct and SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online) databases for articles published between 2001 and June 2014, using the combined English terms "children" and "calcium" or "children" and "vitamin D," each associated with the descriptors "obesity", "adiposity" or "body fat" for both bases (Fig. 1). Age parameters of the World Health Organization12 were used for the definition of "child", considering only articles that included individuals aged up to nine years. Studies that reported the key search words with cross-sectional, longitudinal design and clinical trials were included; review articles, articles that did not study the association between these micronutrients and obesity were excluded. Three independent reviewers performed the search simultaneously. The surveys were compared and only the studies selected by at least two researchers were included.

Figure 1. Detailed flow chart of the search strategy and study selection.

Results

The search resulted in 216 studies on the subject (91 resulting from the search with the descriptor "calcium" and 125 with the descriptor "vitamin D"). Initially, 65 articles were selected for abstract reading, based on title relevance. After reading the abstracts, 10 articles were selected, which were related to the study of the association between body adiposity and the micronutrients of interest. However, two studies were excluded after the full texts were read, as they did not meet the objectives of this review. Thus, eight articles were included in this review, which were published in the period 2001-2014. Among the included articles, five13 - 17 were related to calcium and three18 , 20 , 21 to vitamin D. Figure 1 shows the process flowchart until the selection of the studies included in this review.

Among the studies that evaluated the association between calcium intake and obesity, most had a longitudinal design,13 - 16 with only one cross-sectional study.17 Age range varied from younger children13 , 14 , 16 to the end of childhood.15 , 17

When analyzing the results of the studies (Table 1), four studies showed an inverse association between calcium intake and obesity indicators.13 - 15 , 17 It is noteworthy that, among these, only the study by Skinner et al.14 did not perform statistical adjustments for confounding factor control. Some peculiarities were observed in the study by Moreira et al.,17 with this association being observed only in girls and the study by Dixon et al.,15 found an association only in older non-hypercholesterolemic children (7-10 years). Differences in the obesity parameters of individuals with different calcium intakes were observed in the randomized clinical trial performed by DeJongh, Binkley and Specker16: in children in the lower tertile of dietary calcium intake (<821 mg/day), fat mass gain was lower (0.3±0.5 kg) in the group supplemented with calcium (two tablets of 500 mg elemental calcium as calcium carbonate) than in the placebo group (0.8±1.1 kg).

Table 1. Studies that evaluated the association between calcium or vitamin D and obesity in children, 2001-2014.

| Authors/Year of publication | Country | Study design | Population/Sample | Main results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | Carruth & Skinner12 (2001) |

USA | Longitudinal (retrospective) | Caucasian children, followed from 2-96 months (n=53) | Higher mean intake of calcium, and more daily servings of dairy products were associated with lower BF |

| Skinner et al.13 (2005) | USA | Longitudinal | Caucasian children, followed from 2-96 months (n=52) | Intake of calcium and polyunsaturated fat were negatively associated with BF% | |

| Dixon et al.14 (2005) | USA | Longitudinal | HC non-obese children and non-HCe children aged 4 to 10 years (n=342) | Calcium intake was inversely associated with BMIa sum of skinfolds and trunk SF in non-HC children aged 7 to 10 years. No association found for children aged 4-6 years | |

| Moreira et al.16 (2005) | Portugal | Cross-sectional | Elementary schoolchildren from Portugal aged 7 to 9 years (n=3044) | Inverse association between calcium intake and BMI only in girls | |

| DeJongh, Binkley & Specker15 (2006) |

USA | Longitudinal (randomized, placebo-controlled trial) | Children aged 3 to 5 years (n=178) | Lowest tertile of dietary calcium intake, lower fat mass gain in the calcium-supplemented group compared to the placebo group | |

| Vitamin D | Lee H. A. et al.17 (2013) | Korea | Cross-sectional | Children aged 7 to 9 years (n=205) | Levels of 25(OH)D were inversely associated with adiposity index |

| Lee S.H. et al. 19 (2013) | Korea | Cross-sectional | Children aged 9 years (n=1,660) | Mean levels of 25 (OH) D were lower in children with total or abdominal obesity | |

| Lourenço et al. 20 (2014) | Brazil | Longitudinal | Children younger than 10 years (n=796) | FTO gene was positively associated com weight gain. Vitamin D seems to modify the genetic effects o FTO | |

BMI, Body Mass Index; BF, Body fat; BF%, Body Fat percentage; HC, Hypercholesterolemic; Non-HC, Non-hypercholesterolemic; SF, skin folds; GER, Resting energy expenditure.

Considering the studies that assessed the association between vitamin D and obesity in children, two were cross-sectional18 , 20 and one longitudinal21 (Table 1). In a study with children aged seven to nine years in Korea, Lee et al.18 found an inverse association between vitamin D concentrations and BMI, body fat percentage (BF%), waist circumference, mid-arm circumference and triceps skinfold. In this study, the concentration of 25 (OH) D (25 hydroxyvitamin D) was measured and levels were categorized into three groups, according to the Institute of Medicine (IOM)19: sufficient (≥30 ng/mL), insufficient (20.0-29.9 ng/mL) and deficient (<20 ng/mL). Among the children, 84.4% did not achieve sufficient levels of vitamin D and 17.6% were deficient. Girls had higher levels of vitamin D than boys. Another study found lower levels of vitamin D in obese children when compared to normal weight ones. Serum levels of vitamin D were significantly associated with higher BMI, waist circumference and serum triacylglycerols, as well as lower HDL levels.20 The authors of this study used the same categorization of vitamin D levels of the IOM, but cited another reference.22 Finally, a longitudinal study in the Brazilian Amazon region, followed children from 2007 to 2012 with the objective of evaluating the effect of the FTO gene on BMI modifications during childhood, as well as verifying whether the vitamin D status could modify this effect. With multiple regression models, the authors found an effect of the FTO increasing BMI over the years and the vitamin D deficiency (<75 nmol/L in 32% of the sample in 2007) exacerbating this effect, i.e., further increasing BMI.21 In all these studies on vitamin D, the authors made adjustments for potential confounders.

Discussion

Although the role of calcium in obesity is widely studied in adults, there is a scarcity of studies with children. Among the analyzed articles, some peculiarities were found in the results and this can be related to methodological differences in the studies, such as different methods of dietary assessment (20-hour recall, food records, food frequency questionnaire), as well as the assessed time period and the adjustment of dietary calcium for energy or other possible confounders in the statistical models. Additionally, the dietary source of calcium might also have influenced the effects on obesity. According to Zemel & Miller,23 calcium derived from dairy sources seems to have greater effects when compared to that from supplemental or fortified sources and this probably can be attributed to the presence of other bioactive compounds in dairy products that act synergistically with calcium to reduce adiposity.

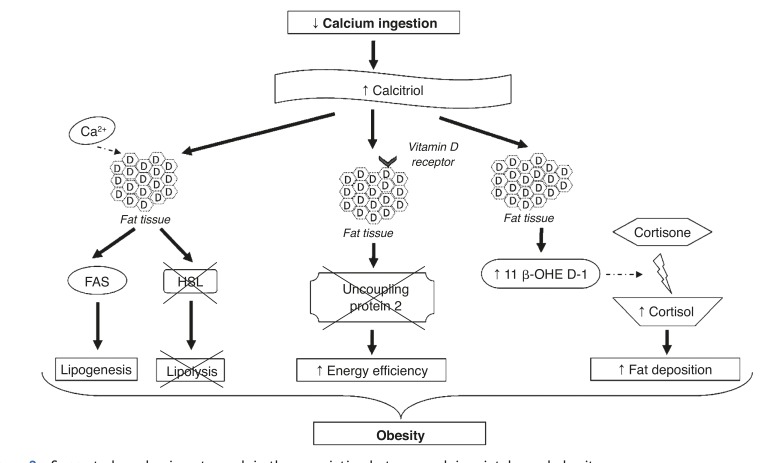

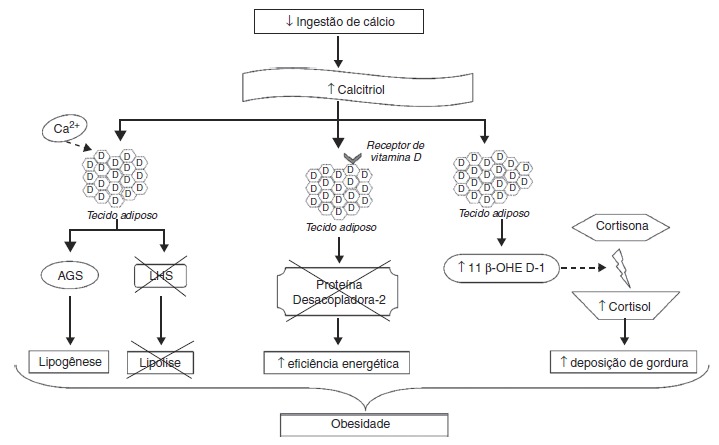

The mechanisms involved in the association between calcium and obesity are shown in Figure 2. These mechanisms are not yet fully elucidated; however, some studies have provided a few plausible explanations.24 , 25 One explanation is that low calcium intake increases serum calcitriol levels, which can stimulate the flow of calcium from adipocytes by vitamin D membrane receptors, identified as associated with rapid membrane response to steroids. The increase in intracellular calcium levels, in turn, increases the activity of fatty acid synthase and inhibits the expression of hormone-sensitive lipase, promoting lipogenesis and inhibiting lipolysis, resulting in the accumulation of body fat. Moreover, calcitriol inhibits the expression of uncoupling protein-2 (involved in the regulation of metabolism, diet-induced thermogenesis and body weight control) through the classic nuclear vitamin D receptors in adipocytes, thereby increasing energy efficiency.24 , 25 Additionally, the regulation by calcitriol of the uncoupling protein-2 and the levels of intracellular calcium seems to have an effect on energy metabolism by affecting adipocyte apoptosis.24

Figure 2. Suggested mechanisms to explain the association between calcium intake and obesity. FAS, Fatty Acid Synthase; HSL, Hormone Sensitive Lipase; 11 b-D-OHE 1, 11 b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase.

The exact mechanism by which calcium intake induces a reduction in abdominal obesity is still unclear, but the autocrine production of cortisol in adipose tissue could explain this effect.24 It has been demonstrated that calcitriol stimulates the expression of 11b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1, which catalyzes the conversion of cortisone to cortisol (involved mainly in fat deposition, especially in the abdominal region) in adipocytes. Thus, it is suggested that diets rich in calcium, by suppressing calcitriol levels, lead to lower body fat accumulation by decreasing cortisol production in adipose tissue.26

Other studies have associated the role of calcium in obesity to the effect of this micronutrient on fecal excretion of fat and appetite regulation. Dietary calcium and calcium supplements may increase the fecal excretion of fat by forming insoluble complexes in the intestine.24 However, studies have shown that this effect is relatively small (especially with calcium supplements).27 , 28 Thus, this mechanism contributes to the antiobesity effect of calcium, but cannot explain it fully.24 , 25 , 27 It is suggested that calcium intake may interfere with appetite regulation; however, this effect was assessed in only a few studies and the hypothesis has not been confirmed.6 , 29

The fact that one of the studies found an inverse association between calcium intake and obesity parameters only in girls17 requires investigation. This could be related to inherent gender characteristics, as the increase in body fat percentage occurs earlier and with greater intensity in females during puberty. Also, boys have a higher content of lean body mass per centimeter of height than girls.30 Moreira et al.17 hypothesized a possible interaction between body fat content and dietary calcium, suggesting that the effects of this micronutrient depend on a higher percentage of body fat, which was not observed in males.

The inverse association between calcium intake and adiposity measures observed only in older children15 can be explained by the growth pattern in this age group. BF gradually decreases during the first years of life, reaching a minimum content between 4 and 6 years. After this period, children go through the "adiposity rebound", with an increase in body weight in preparation for the pubertal growth spurt.31 DeJongh, Binkley and Specker,16 who studied children aged 3-5 years, also suggested that the effect of calcium intake should be higher in the age group in which BF is increased.

The differences found in the obesity parameters of individuals with lower calcium intakes, compared to those with higher intakes, indicate that the effect of increased intake of this micronutrient on BF is more often observed in individuals with low usual calcium intakes.16 This can be explained by the role of calcitriol in calcium absorption. Calcitriol influences active transport by increasing membrane permeability, regulating calcium migration through the intestinal cells and increasing the levels of calbindin.32 , 33 The fraction of absorbed calcium increases as its intake decreases, due to a partial adaptation to this micronutrient restriction, resulting in increased active transport mediated by calcitriol. Thus, the active transport becomes the main mechanism of calcium absorption when its ingestion is low.34

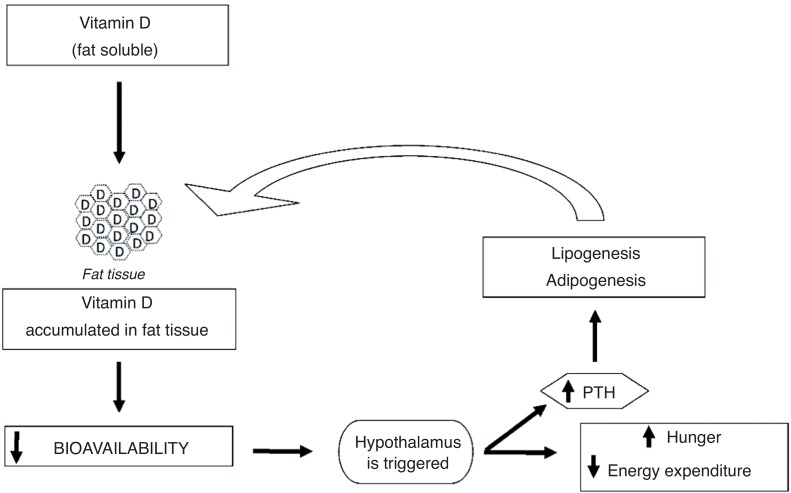

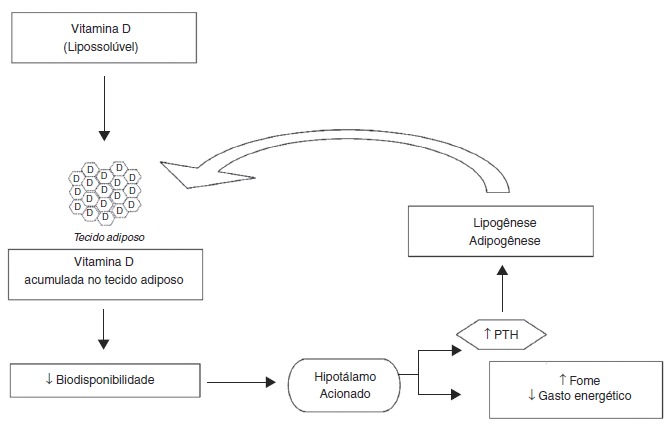

It can be observed that many of the mechanisms that explain adiposity and its association with the assessed micronutrients demonstrate the close association between calcium and the vitamin D present in the metabolic events of adipogenesis, and the fact that the presence or absence of one of them can bring damage not only to bone, but health as a whole. The mechanisms involved in the association between obesity and serum levels of vitamin D have not been described specifically for children. Figure 3 shows the possible mechanisms involved in the association between vitamin D and obesity.

Figure 3. Suggested mechanisms to explain the cyclical association between vitamin D deficiency and increased body fat deposition. PTH, Parathormone.

It is noteworthy that although 25 (OH) D3 (calcidiol) is not the most active metabolite, is the most commonly assessed, as plasma levels of active vitamin D, 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25 (OH) 2D3), are regularly maintained at normal concentrations; furthermore, plasma levels of 25 (OH) D3 are approximately 100 times higher than those of 1,25 (OH) 2D3 and the half-life of 1,25 (OH) 2D3 is approximately six hours, whereas that of 25 (OH) D3 is two to three weeks.11

When comparing serum levels of vitamin D in the children assessed in the study carried out by Lourenço21 in Brazil with a study carried out in the USA,35 higher levels were observed in Brazil. This fact is related to a higher incidence of sunlight in tropical areas, increasing the conversion of vitamin D into its active form, which is measured. Webb, Kline & Holick36 have already explained this phenomenon, showing that latitude and seasons affect the quality and quantity of solar radiation that reach earth, especially UVB spectrum, drastically influencing the cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D. It is also believed that vitamin D deficiency may be related to lack of sun exposure in obese individuals, as they become more sedentary and remain more sheltered from the sun. As these factors are interconnected with worsening in the obesity context, the cause-and-effect association between the two pathologies is not yet clear.37

Lee et al.18 emphasized that differences in serum levels of vitamin D in relation to gender can be explained by the fact that girls reported having a healthier diet for all questions asked. On the other hand, this gender difference was not found in another study.20

The mechanism by which vitamin D influences adiposity is not completely understood, but there are lines of research that try to explain this phenomenon. Vitamin D is fat soluble, and thus it is sequestered and stored in adipocytes. That reduces its bioavailability and triggers the hypothalamus to generate a cascade of reactions that leads to increased feelings of hunger and decreased energy expenditure, to compensate for the lack of the vitamin.37 Among these reactions is the increase in parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels, which promotes lipogenesis38 , 39 and can modulate adipogenesis by suppressing the vitamin D receptor, which inhibits compounds involved in adipocyte differentiation and maturation.39 , 40 In general, it can be observed that the increase in BF can aggravate vitamin D deficiency which, in turn, can further increase the accumulation of fat, creating a cycle (Fig. 3).

For this review, it is necessary to consider the possibility of publication biases, as one can observe a tendency that positive results get to be more frequently published. Some studies17 , 18 , 20 that evaluated the association of calcium and vitamin D with obesity showed a cross-sectional design and it is important to consider the existence of some limitations, especially reverse causality, as the exposure and outcome are collected simultaneously.30 Moreover, it is important to take into account that one of the studies14 did not make adjustments for confounding factors in the statistical analyses, in addition to the small sample size used by others,13 , 14 which can lead to erroneous conclusions. Finally, it is also worth emphasizing that one recognizes the importance of assessing the quality of studies in systematic reviews; however, we emphasize that the existing quality lists and scales used for this evaluation process contains questions that focus on clinical trials. This review included only one trial and, therefore, this assessment was not applied.

Final considerations

The association between calcium and vitamin D with obesity is complex and much remains to be elucidated. Regarding calcium, studies evaluating the association of its intake and measures of obesity in childhood have found significant results when considering characteristics such as age and gender of individuals. Regarding vitamin D, studies are recent and promising. All show an inverse association between serum vitamin D and obesity or measures of adiposity in children, with this association being influenced by the seasons of the year and gender.

It is a consensus that dietary and behavioral habits in early life can affect adult life. Thus, the need for more studies of which sample consists exclusively of children is extremely important, especially in a longitudinal design, as they can clarify the causality of these associations. Calcium and vitamin D, both assessed by dietary intake and by biochemical markers, were associated with obesity.

Thus, considering the protective effect of intake of these nutrients in relation to childhood obesity, public health interventions for prevention can be mostly directed at nutritional education, as they are easily accessible and inexpensive, consequently helping the conducts aimed at preventing chronic diseases associated to overweight and obesity throughout life.

Footnotes

Funding This study did not receive funding.

References

- 1.Tremblay A, Arguin H. Healthy eating at school to compensate for the activity-related obesigenic lifestyle in children and adolescents: the Quebec experience. Adv Nutr. 2011;2:167S-70S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Tremblay A, Arguin H. Healthy eating at school to compensate for the activity-related obesigenic lifestyle in children and adolescents: the Quebec experience. Adv Nutr. 2011;2:167S–170S. doi: 10.3945/an.111.000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buyukinan M, Ozen S, Kokkun S, Saz EU. The relation of vitamin D deficiency with puberty and insulin resistance in obese children and adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25:83-7. [DOI] [PubMed]; Buyukinan M, Ozen S, Kokkun S, Saz EU. The relation of vitamin D deficiency with puberty and insulin resistance in obese children and adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25:83–87. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2011-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Population-based approaches to childhood obesity prevention. Geneva: WHO Document Production Services; 2012. Disponivel em: http://www.who.int/entity/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/WHOnewchildhoodobesityPREVENTION27novHRPRINTOK.pdf; World Health Organization . Population-based approaches to childhood obesity prevention. Geneva: WHO Document Production Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruney TS. Childhood obesity: effects of micronutrients, supplements, genetics, and oxidative stress. J Nurse Pract. 2011:647-53.; Bruney TS. Childhood obesity: effects of micronutrients, supplements, genetics, and oxidative stress. J Nurse Pract. 2011:647–653. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Musharaf S, Al-Othman A, Al-Daghri NM, Krishnaswamy S, Yusuf DS, Alkharfy KM, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and calcium intake in reference to increased body mass index in children and adolescents. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:1081-6. [DOI] [PubMed]; Al-Musharaf S, Al-Othman A, Al-Daghri NM, Krishnaswamy S, Yusuf DS, Alkharfy KM. Vitamin D deficiency and calcium intake in reference to increased body mass index in children and adolescents. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:1081–1086. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1686-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Astrup A. The role of calcium in energy balance and obesity: the search for mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:873-4. [DOI] [PubMed]; Astrup A. The role of calcium in energy balance and obesity: the search for mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:873–874. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.4.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali HI, Ng SW, Zaghloul S, Harrison GG, Qazaq HS, El Sadig M, et al. High proportion of 6 to 18-year-old children and adolescents in the United Arab Emirates are not meeting dietary recommendations. Nutr Res. 2013;33:447-56. [DOI] [PubMed]; Ali HI, Ng SW, Zaghloul S, Harrison GG, Qazaq HS, El Sadig M. High proportion of 6 to 18-year-old children and adolescents in the United Arab Emirates are not meeting dietary recommendations. Nutr Res. 2013;33:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarron D, Morris CD, Henry HJ, Stanton JL. Blood pressure and nutrient intake in the United States. Science. 1984;29:1392-8. [DOI] [PubMed]; McCarron D, Morris CD, Henry HJ, Stanton JL. Blood pressure and nutrient intake in the United States. Science. 1984;29:1392–1398. doi: 10.1126/science.6729459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zemel MB, Shi H, Greer B, Dirienzo D, Zemel PC. Regulation of adiposity by dietary calcium. FASEB J. 2000;14:1132-8. [PubMed]; Zemel MB, Shi H, Greer B, Dirienzo D, Zemel PC. Regulation of adiposity by dietary calcium. FASEB J. 2000;14:1132–1138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bendsen N, Hother A, Jensen S, Lorenzen J, Astrup A. Effect of dairy calcium on fecal fat excretion: a randomized crossover trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32:1816-24. [DOI] [PubMed]; Bendsen N, Hother A, Jensen S, Lorenzen J, Astrup A. Effect of dairy calcium on fecal fat excretion: a randomized crossover trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1816–1824. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911-30. [DOI] [PubMed]; Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911–1930. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Organización Mundial de la Salud. La salud de los jóvenes: un reto y una esperanza. Geneva: OMS; 1995.; Organización Mundial de la Salud . La salud de los jóvenes: un reto y una esperanza. Geneva: OMS; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carruth BR, Skinner JD. The role of dietary calcium and other nutrients in moderating body fat in preschool children. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:559-66. [DOI] [PubMed]; Carruth BR, Skinner JD. The role of dietary calcium and other nutrients in moderating body fat in preschool children. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:559–566. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skinner JD, Bounds W, Carruth BR, Ziegler P. Longitudinal calcium intake is negatively related to children's body fat indexes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:1626-31. [DOI] [PubMed]; Skinner JD, Bounds W, Carruth BR, Ziegler P. Longitudinal calcium intake is negatively related to children's body fat indexes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:1626–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon LB, Pellizzon MA, Jawad AF, Tershakovec AM. Calcium and dairy intake and measures of obesity in hyperand normocholesterolemic children. Obes Res. 2005;13:1727-38. [DOI] [PubMed]; Dixon LB, Pellizzon MA, Jawad AF, Tershakovec AM. Calcium and dairy intake and measures of obesity in hyperand normocholesterolemic children. Obes Res. 2005;13:1727–1738. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeJongh ED, Binkley TL, Specker BL. Fat mass gain is lower in calcium-supplemented than in unsupplemented preschool children with low dietary calcium intakes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1123-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; DeJongh ED, Binkley TL, Specker BL. Fat mass gain is lower in calcium-supplemented than in unsupplemented preschool children with low dietary calcium intakes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1123–1127. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.5.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreira P, Padez C, Mourao I, Rosado V. Dietary calcium and body mass index in Portuguese children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:861-7. [DOI] [PubMed]; Moreira P, Padez C, Mourao I, Rosado V. Dietary calcium and body mass index in Portuguese children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:861–867. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HA, Kim YJ, Lee H, Gwak HS, Park EA, Cho SJ, et al. Association of vitamin D concentrations with adiposity indices among preadolescent children in Korea. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2013;26:849-54. [DOI] [PubMed]; Lee HA, Kim YJ, Lee H, Gwak HS, Park EA, Cho SJ. Association of vitamin D concentrations with adiposity indices among preadolescent children in Korea. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2013;26:849–854. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2012-0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to review dietary reference intakes for vitamin, D and calcium. Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, editors. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington: National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed]; Institute of Medicine Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington: National Academies Press; 2010. Committee to review dietary reference intakes for vitamin,D and calcium. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SH, Kim SM, Park HS, Choi KM, Cho GJ, Ko BJ, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, obesity and the metabolic syndrome among Korean children. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:785-91. [DOI] [PubMed]; Lee SH, Kim SM, Park HS, Choi KM, Cho GJ, Ko BJ. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, obesity and the metabolic syndrome among Korean children. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:785–791. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lourenço BH, Willett L, Cardoso WC. Action Study Team FTO genotype, vitamin D status, and weight gain during childhood. Diabetes. 2014;63:808-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Lourenço BH, Willett L, Cardoso WC. Action Study Team FTO genotype, vitamin D status, and weight gain during childhood. Diabetes. 2014;63:808–814. doi: 10.2337/db13-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266-81. [DOI] [PubMed]; Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zemel MB, Miller SL. Dietary calcium and dairy modulation of adiposity and obesity risk Nutrition reviews. Nutrition Reviews. 2004;62:125-31. [DOI] [PubMed]; Zemel MB, Miller SL. Dietary calcium and dairy modulation of adiposity and obesity risk Nutrition reviews. Nutrition Reviews. 2004;62:125–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zemel MB. The role of dairy foods in weight management. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24 Suppl 6: 537S-46. [DOI] [PubMed]; Zemel MB. The role of dairy foods in weight management. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24(6):537S–5346. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2005.10719502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Major GC, Chaput JP, Ledoux M, St-Pierre S, Anderson GH, Zemel MB, et al. Recent developments in calcium-related obesity research. Obes Rev. 2008;9:428-45. [DOI] [PubMed]; Major GC, Chaput JP, Ledoux M, St-Pierre S, Anderson GH, Zemel MB. Recent developments in calcium-related obesity research. Obes Rev. 2008;9:428–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris KL, Zemel MB. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 modulation of adipocyte glucocorticoid function. Obes Res. 2005;13:670-7. [DOI] [PubMed]; Morris KL, Zemel MB. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 modulation of adipocyte glucocorticoid function. Obes Res. 2005;13:670–677. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobsen R, Lorenzen JK, Toubro S, Krog-Mikkelsen I, Astrup A. Effect of short-term high dietary calcium intake on 24-h energy expenditure, fat oxidation, and fecal fat excretion. Int J Obes. 2005;29:292-301. [DOI] [PubMed]; Jacobsen R, Lorenzen JK, Toubro S, Krog-Mikkelsen I, Astrup A. Effect of short-term high dietary calcium intake on 24-h energy expenditure, fat oxidation, and fecal fat excretion. Int J Obes. 2005;29:292–301. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christensen R, Lorenzen JK, Svith CR, Bartels EM, Melanson EL, Saris WH, et al. Effect of calcium from dairy and dietary supplements on faecal fat excretion: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2009;10:475-86. [DOI] [PubMed]; Christensen R, Lorenzen JK, Svith CR, Bartels EM, Melanson EL, Saris WH. Effect of calcium from dairy and dietary supplements on faecal fat excretion: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2009;10:475–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dougkas A, Reynolds CK, Givens ID, Elwood PC, Minihane AM. Associations between dairy consumption and body weight: a review of the evidence and underlying mechanisms. NRR. 2011;24:72. [DOI] [PubMed]; Dougkas A, Reynolds CK, Givens ID, Elwood PC, Minihane AM. Associations between dairy consumption and body weight: a review of the evidence and underlying mechanisms. NRR. 2011;24:72–72. doi: 10.1017/S095442241000034X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menezes AM. Noções basicas de epidemiologia [pagina da Internet]. Epidemiologia das doenças respiratórias Ministério Público de Tocantins [acessado em 11 de junho de 2014]. Disponivel em: http://www.mpto.mp.br/static/caops/patrimonio-publico/files/files/nocoes-de-epidemiologia.pdf; Menezes AM. Noções basicas de epidemiologia [pagina da Internet]. Epidemiologia das doenças respiratórias Ministério Público de Tocantins. [11 de junho de 2014]. a Disponivel em: http://www.mpto.mp.br/static/caops/patrimonio-publico/files/files/nocoes-de-epidemiologia.pdf.

- 31.Whitaker RC, Pepe MS, Wright JA, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Early adiposity rebound and the risk of adult obesity. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E5. [DOI] [PubMed]; Whitaker RC, Pepe MS, Wright JA, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Early adiposity rebound and the risk of adult obesity. Pediatrics. 1998;101: doi: 10.1542/peds.101.3.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bronner F, Pansu D. Nutritional aspects of calcium absorption. J Nutr. 1999;129:9-12. [DOI] [PubMed]; Bronner F, Pansu D. Nutritional aspects of calcium absorption. J Nutr. 1999;129:9–12. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guéguen L, Pointillart A. The bioavailability of dietary calcium. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19:119S-36S. [DOI] [PubMed]; Guéguen L, Pointillart A. The bioavailability of dietary calcium. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19:119S–136S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Finneran S. Calcium absorption on high and low calcium intakes in relation to vitamin D receptor genotype. JCEM. 1995;12:3657-61. [DOI] [PubMed]; Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Finneran S. Calcium absorption on high and low calcium intakes in relation to vitamin D receptor genotype. JCEM. 1995;12:3657–3661. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.12.8530616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilbert-Diamond D, Baylin A, Mora-Plazas M, Marin C, Arsenault JE, Hughes MD, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and anthropometric indicators of adiposity in school-age children: a prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1446-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Gilbert-Diamond D, Baylin A, Mora-Plazas M, Marin C, Arsenault JE, Hughes MD. Vitamin D deficiency and anthropometric indicators of adiposity in school-age children: a prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1446–1451. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb AR, Kline L, Holick MF. Influence of season and latitude on the cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3 : exposure to winter sunlight in Boston and Edmonton will not promote vitamin D3 synthesis in human skin. JCEM. 1988;67:373-8. [DOI] [PubMed]; Webb AR, Kline L, Holick MF. Influence of season and latitude on the cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3: exposure to winter sunlight in Boston and Edmonton will not promote vitamin D3 synthesis in human skin. JCEM. 1988;67:373–378. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-2-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuch NJ, Garcia VC, Martini LA. Vitamin D and endocrine diseases. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab. 2009;35:625-33. [DOI] [PubMed]; Schuch NJ, Garcia VC, Martini LA. Vitamin D and endocrine diseases. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab. 2009;35:625–633. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302009000500015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun X, Zemel MB. 1Alfa, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D and corticosteroid regulate adipocyte nuclear vitamin D receptor. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32:1305-11. [DOI] [PubMed]; Sun X, Zemel MB. 1Alfa, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D and corticosteroid regulate adipocyte nuclear vitamin D receptor. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1305–1311. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCarty MF, Thomas CA. PTH. excess may promote weight gain by impeding catecholamine-induced lipolysis-implications for the impact of calcium, vitamin D, and alcohol on body weight. Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:535-42. [DOI] [PubMed]; McCarty MF, Thomas CA. PTH: excess may promote weight gain by impeding catecholamine-induced lipolysis-implications for the impact of calcium, vitamin D, and alcohol on body weight. Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:535–542. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(03)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wood RJ. Vitamin D and adipogenesis: new molecular insights. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:40-6. [DOI] [PubMed]; Wood RJ. Vitamin D and adipogenesis: new molecular insights. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:40–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]